The extraordinary career of Granville Redmond:

deaf artist and silent movie actor

By Philip McCouat

In October 2006, a painting titled Seascape at Twilight was stolen from the Los Angeles Fine Art Gallery. Shortly after, a person known as Matthew Taylor sold the painting to a Beverly Hills dealer for $85,000, falsely stating that his mother had owned it for several years. The scam was later uncovered and Taylor was duly convicted for selling a stolen work [1]. Happily, too, the painting itself was also eventually safely recovered.

In October 2006, a painting titled Seascape at Twilight was stolen from the Los Angeles Fine Art Gallery. Shortly after, a person known as Matthew Taylor sold the painting to a Beverly Hills dealer for $85,000, falsely stating that his mother had owned it for several years. The scam was later uncovered and Taylor was duly convicted for selling a stolen work [1]. Happily, too, the painting itself was also eventually safely recovered.

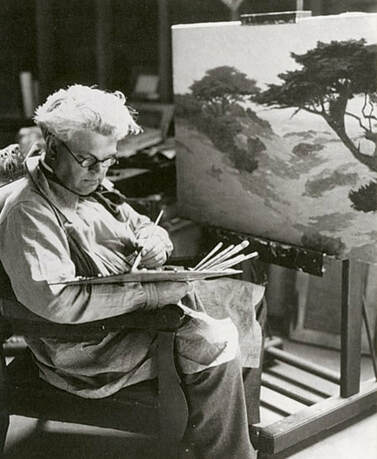

It was a brief moment of posthumous fame for the painter of the work, the Californian artist Granville Redmond, who had died 70 years before. Redmond had actually had a quite remarkable career, for not only was he a fine impressionist painter, he was also a talented actor and even mentored the legendary Charles Chaplin. And his achievement was actually all the more remarkable, as for almost all of his life he was a deaf mute, totally unable to hear or speak.

Our story today examines this artist’s intriguingly varied and creative life [2].

Our story today examines this artist’s intriguingly varied and creative life [2].

Redmond’s early struggles

Granville Redmond was born in Philadelphia on 9 March 1871. When he was just two years old, a bout of scarlet fever left him totally and permanently deaf [3]. In addition, without the continued stimulus of hearing spoken language, what little verbal skills he had previously acquired quickly atrophied. He would never speak again.

At this time, deafness and muteness were commonly, but incorrectly, regarded as signs of retardation. Granville was, however, lucky in one respect -- as a result of a family move to San Jose, he lived close to the respected California School for the Deaf in Berkeley. On enrolling there as a boarder from the time he was eight, he learned sign language, and for the first time found himself in the company of other people who were able to communicate without hearing.

As it happened [4], the School’s superintendent strongly believed that training in the arts, drawing, painting, modelling and carving were ideal subjects for his deaf students, enabling them to find useful work in many areas. Redmond himself showed early artistic talent and came under the particular influence of one of the teachers, Theophilus d’Estrella, who had been born deaf, and had a special interest in art, particularly paintings done in the open air. Redmond quickly blossomed, doing his first oil painting at only 11.

On his eventual graduation, he was granted funds to attend classes in art and drawing at the California School of Design, under the influential leadership of Arthur Mathews, an early champion of Californian painting. Here, Redmond was able to mix with hearing students. At this early stage he was also developing his non-verbal communication skills, participating in plays, set design and pantomime [5]. All these skills would play an important part in the development of his later careers.

At the School of Design, Redmond formed a strong bond with fellow art student Gottardo Piazzoni who, aided by exceptional language skills, quickly learned sign language. Their long friendship, with many sketching and paintings trips together, would last throughout their lives.

Redmond’s continuing progress was later rewarded by a grant to study in Paris for two years at the Academie Julian, where he stayed with the successful deaf sculptor Douglas Tilden. He would go on to spend five years in Paris, ekeing out a somewhat precarious existence, with the help of frequent loans from benefactors and family, sometimes surviving by exchanging a meal for a painting. However, while he had some successes, and his style and ability steadily continued to develop, he finally had to give up his dream of financial success in France. In 1898 returned to Los Angeles.

At this time, deafness and muteness were commonly, but incorrectly, regarded as signs of retardation. Granville was, however, lucky in one respect -- as a result of a family move to San Jose, he lived close to the respected California School for the Deaf in Berkeley. On enrolling there as a boarder from the time he was eight, he learned sign language, and for the first time found himself in the company of other people who were able to communicate without hearing.

As it happened [4], the School’s superintendent strongly believed that training in the arts, drawing, painting, modelling and carving were ideal subjects for his deaf students, enabling them to find useful work in many areas. Redmond himself showed early artistic talent and came under the particular influence of one of the teachers, Theophilus d’Estrella, who had been born deaf, and had a special interest in art, particularly paintings done in the open air. Redmond quickly blossomed, doing his first oil painting at only 11.

On his eventual graduation, he was granted funds to attend classes in art and drawing at the California School of Design, under the influential leadership of Arthur Mathews, an early champion of Californian painting. Here, Redmond was able to mix with hearing students. At this early stage he was also developing his non-verbal communication skills, participating in plays, set design and pantomime [5]. All these skills would play an important part in the development of his later careers.

At the School of Design, Redmond formed a strong bond with fellow art student Gottardo Piazzoni who, aided by exceptional language skills, quickly learned sign language. Their long friendship, with many sketching and paintings trips together, would last throughout their lives.

Redmond’s continuing progress was later rewarded by a grant to study in Paris for two years at the Academie Julian, where he stayed with the successful deaf sculptor Douglas Tilden. He would go on to spend five years in Paris, ekeing out a somewhat precarious existence, with the help of frequent loans from benefactors and family, sometimes surviving by exchanging a meal for a painting. However, while he had some successes, and his style and ability steadily continued to develop, he finally had to give up his dream of financial success in France. In 1898 returned to Los Angeles.

The maturing artist: techniques and genres

Redmond felt like a failure on his return. He was 27, seemingly with little to show for his life so far, and confused thoughts about his financial future [6]. But, in one of the crucial turning points of his life, he overcame his depression, found a suitable studio and started painting again. Significantly, he also assumed a new independent identity -- instead of his given name of Grenville Seymour Redmond, which he shared with an uncle, he dropped the Seymour, and changed Grenville to Granville. He also married Carrie, a graduate from the Illinois Institute of the Deaf. By 1901 he was finally making his way as an artist and illustrator, and newspaper articles had begun appearing on him [7]. His career began to blossom.

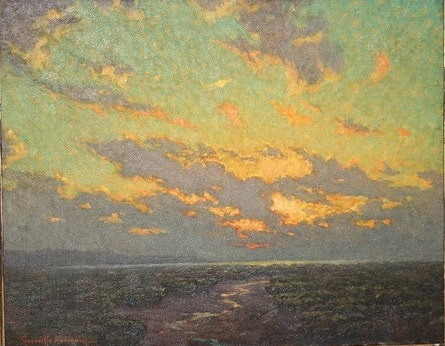

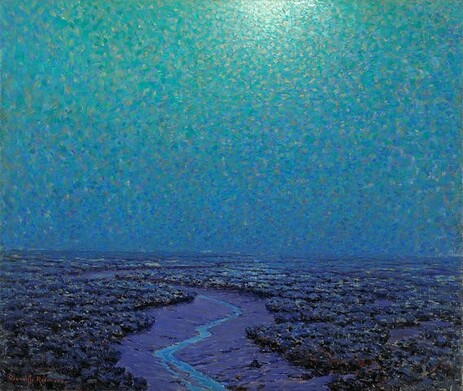

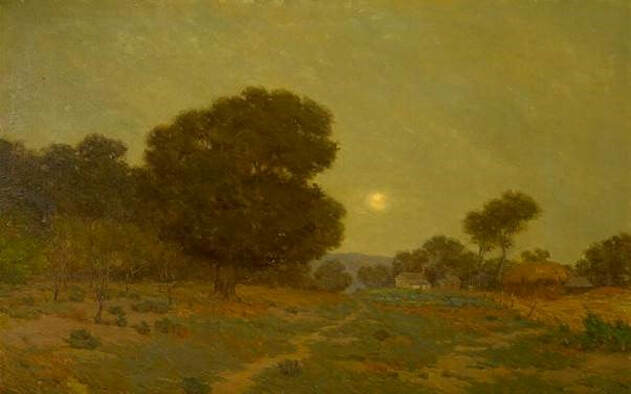

Redmond’s early paintings tended to be quiet, muted and moody, such as dimly-lit nocturnes in shades of brown, grey and dark blue. These “tonalist” works would always remain his favourites, possibly because they expressed his inner world. He later commented that he liked works of “solitude and silence” [8].

Redmond’s early paintings tended to be quiet, muted and moody, such as dimly-lit nocturnes in shades of brown, grey and dark blue. These “tonalist” works would always remain his favourites, possibly because they expressed his inner world. He later commented that he liked works of “solitude and silence” [8].

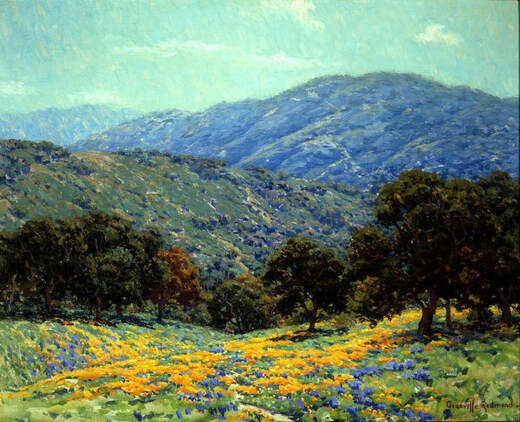

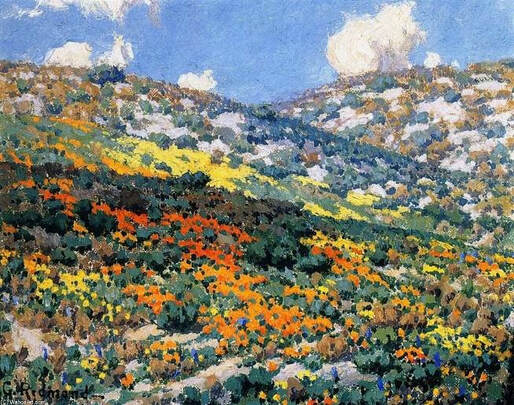

As time went by, however, he began to adopt the higher colour tones favoured by the Impressionists, creating colour harmonies and avoiding dark colours or contrasts. These paintings were almost always of the Californian countryside and coast. He often went there with Piazzoni on sketching and painting trips, in keeping with the French practice of working in the outdoors, pioneered especially by the Barbizon school of artists.

The paintings he created were often highly atmospheric, capturing the distinctive, ever-changing light effects of morning mist, marine fog, afternoon haze or breezy clarity of a summer sky or moonlight [9]. He remained fascinated by the effects of light, a strong believer in the importance of capturing the decisive moment – he believed that no-one should sketch from nature for more than fifteen minutes at a time --“by that time everything has changed” [10].

One of his signature themes were depictions of the springtime fields of golden Californian poppies. These became enormously popular – in his view, too popular. He once lamented that people would not buy his favourite tonalist paintings. Instead “they all seem to want poppies”. He could scarcely paint them quickly enough to satisfy the demand [11].

The paintings he created were often highly atmospheric, capturing the distinctive, ever-changing light effects of morning mist, marine fog, afternoon haze or breezy clarity of a summer sky or moonlight [9]. He remained fascinated by the effects of light, a strong believer in the importance of capturing the decisive moment – he believed that no-one should sketch from nature for more than fifteen minutes at a time --“by that time everything has changed” [10].

One of his signature themes were depictions of the springtime fields of golden Californian poppies. These became enormously popular – in his view, too popular. He once lamented that people would not buy his favourite tonalist paintings. Instead “they all seem to want poppies”. He could scarcely paint them quickly enough to satisfy the demand [11].

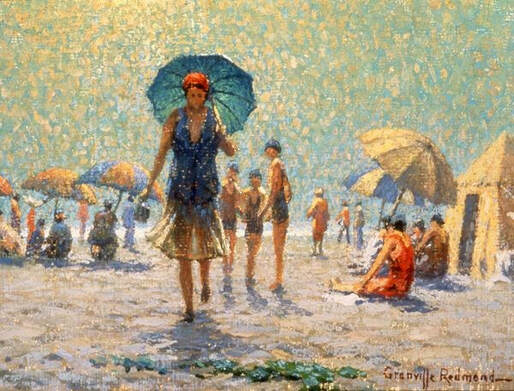

In keeping with his preference for solitude and silence, Redmond’s paintings were almost always unpeopled or, in those cases where people do appear, they were very subordinate. This feature adds to their feeling of quietness. It is significant that perhaps the only work in which people feature prominently is titled Talk at the Beach. It seems that Redmond associated the outside world with talking, contrasting with his inner world of silence.

At the movies with Chaplin

In 1916, despite his previous years of success, Redmond was forced to decide on a radical change of direction. The increasing impact of the Great War had contributed to a sharp downturn in the art market, galleries were closing, and collectors were beset by other concerns. Redmond had built up a formidable reputation, but, like many other artists at the time, he found that painting could no longer support his family as it had done for so many years. As he looked round for alternative supplementary sources of income [12], it was perhaps inevitable that he might turn to one Californian industry that was still held promise – the movie business.

In many ways, the movies were a natural fit for him. Their crucial attribute was that, at this stage, they were still silent -- “talkies” were still way off in the future. As no spoken dialogue was involved, or even mouthed dialogue, mute actors could compete with speaking actors on an equal footing [13]. In fact, Redmond actually had one advantage over many hearing actors, in that as a result of his early experiences he had become a skilled mime performer and an excellent non-verbal communicator. As art critic Anthony Anderson later recalled, “in his student days [Redmond] used to delight all Paris with the stories he told with his hands, his shoulders and his vivid play of facial expressions, and I remember how delightfully he used to entertain us in this way when he had left the studio”[14].

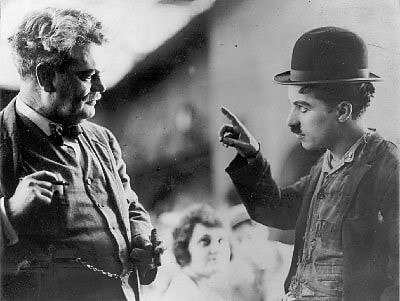

Armed with some letters of introduction from the helpful Anderson, Redmond tried his luck in Hollywood. Somehow -- accounts differ -- he came into contact with Charlie Chaplin, the legendary silent film actor and filmmaker who even then, as just 28, was already fast becoming world-famous.

Chaplin had himself had a very challenging childhood. His mother had been committed to a mental asylum, and his alcoholic father played little role in his life. Chaplin spent much of his childhood living in orphanages. So it is understandable that he may have had considerable empathy with Redmond’s quite different but similarly challenging life experience. It is also possible that Chaplin was keen to establish his own “high art” credentials, given the “low comedy” world in which he worked [15]. In any event, he was highly impressed, not only by Redmond’s artistic talent but also by his gift for communication. As a result, Chaplin made a number of decisions that would give Redmond’s career a jump-start in a number of ways.

Firstly, he gave Redmond small parts in a series of films, starting with a role as a saloon owner in A Dog’s Life (I918) and progressing to an art-appreciating friend in The Kid (1921) and a sculptor in City Lights (1931). These in turn led to parts in films by other filmmakers, such as Douglas Fairbanks (The Three Musketeers (1921)) and Raymond Griffiths (You’d Be Surprised (1926)). Acting in roles that typically did not involve sign language or deaf characters, Redmond would go on to become the most well-known of the deaf actors in Hollywood, as well as an inspiration to the deaf community [16].

Chaplin also boosted Redmond’s artistic career, setting him up in a dedicated painting studio within the Property Room building of Chaplin’s major film complex. Along with Fairbanks and Griffiths, he also commissioned paintings from Redmond for his private collection.

In many ways, the movies were a natural fit for him. Their crucial attribute was that, at this stage, they were still silent -- “talkies” were still way off in the future. As no spoken dialogue was involved, or even mouthed dialogue, mute actors could compete with speaking actors on an equal footing [13]. In fact, Redmond actually had one advantage over many hearing actors, in that as a result of his early experiences he had become a skilled mime performer and an excellent non-verbal communicator. As art critic Anthony Anderson later recalled, “in his student days [Redmond] used to delight all Paris with the stories he told with his hands, his shoulders and his vivid play of facial expressions, and I remember how delightfully he used to entertain us in this way when he had left the studio”[14].

Armed with some letters of introduction from the helpful Anderson, Redmond tried his luck in Hollywood. Somehow -- accounts differ -- he came into contact with Charlie Chaplin, the legendary silent film actor and filmmaker who even then, as just 28, was already fast becoming world-famous.

Chaplin had himself had a very challenging childhood. His mother had been committed to a mental asylum, and his alcoholic father played little role in his life. Chaplin spent much of his childhood living in orphanages. So it is understandable that he may have had considerable empathy with Redmond’s quite different but similarly challenging life experience. It is also possible that Chaplin was keen to establish his own “high art” credentials, given the “low comedy” world in which he worked [15]. In any event, he was highly impressed, not only by Redmond’s artistic talent but also by his gift for communication. As a result, Chaplin made a number of decisions that would give Redmond’s career a jump-start in a number of ways.

Firstly, he gave Redmond small parts in a series of films, starting with a role as a saloon owner in A Dog’s Life (I918) and progressing to an art-appreciating friend in The Kid (1921) and a sculptor in City Lights (1931). These in turn led to parts in films by other filmmakers, such as Douglas Fairbanks (The Three Musketeers (1921)) and Raymond Griffiths (You’d Be Surprised (1926)). Acting in roles that typically did not involve sign language or deaf characters, Redmond would go on to become the most well-known of the deaf actors in Hollywood, as well as an inspiration to the deaf community [16].

Chaplin also boosted Redmond’s artistic career, setting him up in a dedicated painting studio within the Property Room building of Chaplin’s major film complex. Along with Fairbanks and Griffiths, he also commissioned paintings from Redmond for his private collection.

A mutually beneficial relationship

It seems that Chaplin believed that Redmond’s deafness actually contributed a special quality to his art. He is reported as saying, “Something puzzles me about Redmond’s pictures. There’s such a wonderful joyousness about them all. Look at the gladness in that sky, the riot of colour in those flowers. Sometimes I think that the silence in which he lives has developed in him some sense, some great capacity for happiness in which we others are lacking… I could look at it for hours" End notes for The extraordinary career of Granville Redmond, deaf artist and silent movie actor [17].

On a communication level, it seems that both men learned from each other. Although Chaplin was already a master in non-verbal communication, it is likely that he was able to obtain valuable additional insights from Redmond, and it appears that Redmond may even have taught Chaplin sign language. In A Dog’s Life, deaf members of the audience readily picked up Chaplin’s use of natural signs for “baby” and “children”. Redmond commented admiringly that “Chaplin is exceptionally graceful on his hands”[18].

Their personal relationship was also mutually beneficial. As The California News reported, “Chaplin is fond of Redmond because no oral conversation is possible between them. Instead they talk in signs which is soothing to Chaplin, who tries to avoid people who talk too much, which gets on his nerves” [19]. For his part, Redmond felt that he benefited from communicating with hearing people in the film industry who themselves had learned to talk on their hands, acknowledging that “a good deal of my knowledge [was] accumulated from the hearing” [20]. Redmond felt that because deafness can lead to a feeling of being cut-off from the world, the “Deaf are better off in communicating with their pads and mingling, if possible, more with hearing people, thus enlarging views with one another. This applies as well both to the art and business world” [21].

On a communication level, it seems that both men learned from each other. Although Chaplin was already a master in non-verbal communication, it is likely that he was able to obtain valuable additional insights from Redmond, and it appears that Redmond may even have taught Chaplin sign language. In A Dog’s Life, deaf members of the audience readily picked up Chaplin’s use of natural signs for “baby” and “children”. Redmond commented admiringly that “Chaplin is exceptionally graceful on his hands”[18].

Their personal relationship was also mutually beneficial. As The California News reported, “Chaplin is fond of Redmond because no oral conversation is possible between them. Instead they talk in signs which is soothing to Chaplin, who tries to avoid people who talk too much, which gets on his nerves” [19]. For his part, Redmond felt that he benefited from communicating with hearing people in the film industry who themselves had learned to talk on their hands, acknowledging that “a good deal of my knowledge [was] accumulated from the hearing” [20]. Redmond felt that because deafness can lead to a feeling of being cut-off from the world, the “Deaf are better off in communicating with their pads and mingling, if possible, more with hearing people, thus enlarging views with one another. This applies as well both to the art and business world” [21].

Redmond eventually retired from the movie business as talking pictures took over. As always, he continued to paint successfully, right up to his death in 1935. It is reported that Chaplin paid the expenses of his final illness, and sent a huge wreath to his funeral in the shape of an artist’s palette [22].

Conclusion

Once, when asked if deafness had ever inconvenienced him, Redmond had an unexpected answer, laughingly pointing to a cluster of rattles on the wall. For a deaf person painting outdoors in the California sunshine, the unheard approach of rattlesnakes was indeed a real occupational hazard, even more so than for hearing artists [23].

Of course, on a more basic level, there is no doubt that Redmond’s deafness posed challenges that may well have defeated others. However, a combination of substantial talent, a dose of luck, the support of others and a good deal of personal determination enabled him to achieve considerable heights. And, perhaps counter-intuitively, his deafness may even have assisted him in some ways, particularly as it led to his association with Chaplin, with benefits for both his silent film and art careers.

Like many others, Redmond’s life was affected by a series of crucial turning points, at each of which a different outcome may have resulted in his life assuming a totally different direction – his fortunate association with the California School for the Deaf, which set him on an artistic path; his determination not to give up on his return from Paris; and his willingness to step outside his comfort zone by taking up a completely new career in his 40s.

Today, his works continue to be sold for high prices [24]. His work is held in the collections of many institutions, such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Stanford University Museum. His paintings now, more than ever, speak for themselves.

© Philip McCouat 2019, First published January 2019.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “The extraordinary career of Granville Redmond: deaf artist and silent movie actor”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to HOME

Of course, on a more basic level, there is no doubt that Redmond’s deafness posed challenges that may well have defeated others. However, a combination of substantial talent, a dose of luck, the support of others and a good deal of personal determination enabled him to achieve considerable heights. And, perhaps counter-intuitively, his deafness may even have assisted him in some ways, particularly as it led to his association with Chaplin, with benefits for both his silent film and art careers.

Like many others, Redmond’s life was affected by a series of crucial turning points, at each of which a different outcome may have resulted in his life assuming a totally different direction – his fortunate association with the California School for the Deaf, which set him on an artistic path; his determination not to give up on his return from Paris; and his willingness to step outside his comfort zone by taking up a completely new career in his 40s.

Today, his works continue to be sold for high prices [24]. His work is held in the collections of many institutions, such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Stanford University Museum. His paintings now, more than ever, speak for themselves.

© Philip McCouat 2019, First published January 2019.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “The extraordinary career of Granville Redmond: deaf artist and silent movie actor”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to HOME

End Notes

[1] Taylor was also alleged to have been involved in tax evasion. He also allegedly had the habit of buying works by lesser-known artists, and replacing their signatures with forged signatures of famous artists such as Claude Monet. For more about him, see https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/losangeles/press-releases/2011/florida-man-arrested-on-charges-of-selling-stolen-art-and-selling-forged-paintings-for-millions-of-dollars

[2] For much of the biographical information in this article I am indebted to Mary Jean Haley, “Granville Redmond, a triumph of talent and temperament”, with Introduction by Harvey Jones, and Chronology by Mildred Albronda, Exhibition Cat, The Oakland Museum, Oakland 1988.

[3] In the 19th century, scarlet fever, which previously had been relatively rare, became a major disease of the young. The discovery of antibiotics has now largely prevented scarlet fever from causing deafness. Public health measures have also played a critical role.

[4] Haley, op cit at 3.

[5] Haley, op cit at 5.

[6] Haley, op cit at 17.

[7] Haley, op cit at 19.

[8] Haley, op cit at 34.

[9] Jones, Introduction, op cit at xii.

[10] Haley, op cit at 34, citing interview with art critic Arthur Millier, March 1931.

[11] Haley, op cit at 34.

[12] Haley, op cit at 28 onwards.

[13] Conversely, silent movies were as accessible to deaf viewers as to hearing viewers.

[14] Cited in Haley, op cit at 29.

[15] Richard Ward, "Even a Tramp Can Dream: An Examination of the Clash Between "High Art" and "Low Art" in the Films of Charlie Chaplin", Studies in Popular Culture 32, no. 1 (2009): 103-16.

[16] John S Schuman, "The Silent Film Era: Silent Films, NAD Films, and the Deaf Community’s Response", Sign Language Studies 4, no. 3 (2004): 231-38.

[17] Conversation in November 1925, reported by A V Ballin, with Chaplin referring to the painting Low Tide, which Redmond had just completed for Chaplin’s private collection, cited at Haley, op cit at 30.

[18] Haley, op cit at 29-32, citing 1929 letter by Redmond.

[19] Article in March 1929, italics added, cited in Haley, op cit at 31.

[20] Apart from Chaplin himself, these included his cinematographer Rolland Totheroh, who was excellent, and a director Eddie Sutherland, who “talked like lightning”: Haley, op cit at 32.

[21] Haley, op cit at 32.

[22] Thomas R. Reynolds, “Granville Redmond's Tonalism” http://www.thomasreynolds.com/gr_b.html

[23] Haley, op cit at 34, citing interview with Millier.

[24] For example, the stolen painting, Seascape at Twilight, had reportedly been on-sold by the dealer for $236,000.

© Philip McCouat 2019

Return to HOME

[2] For much of the biographical information in this article I am indebted to Mary Jean Haley, “Granville Redmond, a triumph of talent and temperament”, with Introduction by Harvey Jones, and Chronology by Mildred Albronda, Exhibition Cat, The Oakland Museum, Oakland 1988.

[3] In the 19th century, scarlet fever, which previously had been relatively rare, became a major disease of the young. The discovery of antibiotics has now largely prevented scarlet fever from causing deafness. Public health measures have also played a critical role.

[4] Haley, op cit at 3.

[5] Haley, op cit at 5.

[6] Haley, op cit at 17.

[7] Haley, op cit at 19.

[8] Haley, op cit at 34.

[9] Jones, Introduction, op cit at xii.

[10] Haley, op cit at 34, citing interview with art critic Arthur Millier, March 1931.

[11] Haley, op cit at 34.

[12] Haley, op cit at 28 onwards.

[13] Conversely, silent movies were as accessible to deaf viewers as to hearing viewers.

[14] Cited in Haley, op cit at 29.

[15] Richard Ward, "Even a Tramp Can Dream: An Examination of the Clash Between "High Art" and "Low Art" in the Films of Charlie Chaplin", Studies in Popular Culture 32, no. 1 (2009): 103-16.

[16] John S Schuman, "The Silent Film Era: Silent Films, NAD Films, and the Deaf Community’s Response", Sign Language Studies 4, no. 3 (2004): 231-38.

[17] Conversation in November 1925, reported by A V Ballin, with Chaplin referring to the painting Low Tide, which Redmond had just completed for Chaplin’s private collection, cited at Haley, op cit at 30.

[18] Haley, op cit at 29-32, citing 1929 letter by Redmond.

[19] Article in March 1929, italics added, cited in Haley, op cit at 31.

[20] Apart from Chaplin himself, these included his cinematographer Rolland Totheroh, who was excellent, and a director Eddie Sutherland, who “talked like lightning”: Haley, op cit at 32.

[21] Haley, op cit at 32.

[22] Thomas R. Reynolds, “Granville Redmond's Tonalism” http://www.thomasreynolds.com/gr_b.html

[23] Haley, op cit at 34, citing interview with Millier.

[24] For example, the stolen painting, Seascape at Twilight, had reportedly been on-sold by the dealer for $236,000.

© Philip McCouat 2019

Return to HOME