Lost masterpieces of ancient Egyptian art from the Nebamun tomb-chapel

|

Sometime in 1820, on the west bank of the Nile at Luxor, a young Greek fortune seeker made the greatest discovery of his life -- an ancient tomb, seemingly undisturbed for centuries, with magnificent rich decorations almost as fresh as the day they were created more than 3,000 years before.

|

More Journal articles on Egypt:

|

The vivid paintings that he would roughly hack from the tomb walls would eventually come to be regarded as possibly the greatest pictures we have from ancient Egypt, and among the greatest treasures of the British Museum.

In this article we examine how and why these paintings were created, how they were subsequently appropriated by European museums, and how they became the subject of political and religious censorship. Finally, we look at how they have been creatively adapted in modern day paintings, ranging from the precise historical pageantry of Alma-Tadema to the exotic Tahitian art of Gauguin.

In this article we examine how and why these paintings were created, how they were subsequently appropriated by European museums, and how they became the subject of political and religious censorship. Finally, we look at how they have been creatively adapted in modern day paintings, ranging from the precise historical pageantry of Alma-Tadema to the exotic Tahitian art of Gauguin.

Pt 1: DISCOVERY

The early nineteenth century was an age of nationalist adventurers and the rapid growth of museums. At this time, museums generally built their collections by purchasing items from private individuals, rather than conducting their own institutional digs. There was little appreciation of cultural patrimony or the rights of the country of origin – rather, the seizing and export of cultural artifacts was likened to having “a lost child restored to the great family of science and art, which is of no country, whose home is the world” [1]. Such noble internationalist sentiments were, of course, not applied to European artworks, but rather to those classed as primitive, backward, exotic or native, and therefore open to appropriation by the more “civilised” countries.

In view of the potential rewards, there was naturally great rivalry – even violence -- between private collectors, and between nationalities. This applied particularly in Egypt, which was enjoying a sudden surge in interest, following Napoleon’s occupation of that country in 1798 and the general opening up of the country by the Egyptian authorities [2]. In the potential treasure troves of the Thebes Valley, some 500 km south of Cairo, the chief rivalry was played out between the English, who predominantly favoured the west bank of the Nile, and the French on the East Bank.

In view of the potential rewards, there was naturally great rivalry – even violence -- between private collectors, and between nationalities. This applied particularly in Egypt, which was enjoying a sudden surge in interest, following Napoleon’s occupation of that country in 1798 and the general opening up of the country by the Egyptian authorities [2]. In the potential treasure troves of the Thebes Valley, some 500 km south of Cairo, the chief rivalry was played out between the English, who predominantly favoured the west bank of the Nile, and the French on the East Bank.

On the English side, one of the main players was Henry Salt, the British Consul-General (Fig 1), who had been encouraged to collect by Sir Joseph Banks, a trustee of the British Museum at the time. From 1819, Salt’s agent was a young Greek, Giovanni (Yanni) d’Athanasi [3]. It was during his excavations on Salt’s behalf that d’Athanasi would make his momentous discovery.

The Nebamun tomb

The Nebamun tomb was built about 1350-1400 BC. For various reasons, d’Athanasi would always remain very secretive about its exact location, and its precise whereabouts still remain a mystery. However, we can say with some confidence that it was at Thebes (present day Luxor), on the west bank of the Nile, in the area of the Tombs of the Nobles, between the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens (Fig 2). The tomb would have been cut into the rock, and would have faced eastwards, towards the “land of the living”.

Typically, it would have been entered through a doorway in a terraced courtyard. This would lead into the tomb chapel, where most of the painted decorations would have appeared. Below that, accessible through a vertical shaft, would have been the actual burial chamber where Nebamun’s coffined mummy lay. After his funeral, this chamber would have been sealed off, but his family may have continued to visit the tomb chapel itself, performing rituals and prayers, providing an important link between the dead and the living [4].

Typically, it would have been entered through a doorway in a terraced courtyard. This would lead into the tomb chapel, where most of the painted decorations would have appeared. Below that, accessible through a vertical shaft, would have been the actual burial chamber where Nebamun’s coffined mummy lay. After his funeral, this chamber would have been sealed off, but his family may have continued to visit the tomb chapel itself, performing rituals and prayers, providing an important link between the dead and the living [4].

Fig 3: Present day village of Gurna, on the West Bank, used as d’Athanasi’s base, and showing some tomb excavations: https://egyptsites.wordpress.com

Of course, when found by d’Athanasi, all this structure would have been covered, perhaps requiring significant excavation. D’Athanasi would, however, have realised the magnitude of his find as soon as he entered the tomb chapel and its richly decorated walls were revealed to him.

Of course, when found by d’Athanasi, all this structure would have been covered, perhaps requiring significant excavation. D’Athanasi would, however, have realised the magnitude of his find as soon as he entered the tomb chapel and its richly decorated walls were revealed to him.

The museum takes control

uring this era, archaeological techniques were extremely primitive. D’Athanasi removed what he wanted from the Nebamun tomb simply by hacking and gouging fragments from the walls of the tomb. Parkinson describes how d’Athanasi’s workmen “probably cut into the plaster surface of the walls with knives and saws, outlining rectangular pieces which they then pried off the walls with implements such as crowbars. Sometimes they removed the full depth of the mud plaster, but sometimes they carried away only a very thin layer, and the edges inevitably suffered cracking and disintegration” [5].

Ten of the fragments taken by d’Athanasi were included in the first, huge, batch of collections that Henry Salt sent back to the British Museum [6]. After much haggling, the Museum settled for what Salt described as the “miserable sum” of £2,000, apparently not enough to even cover his expenditure [7]. After Salt died in 1827, d’Athanasi offered his services to the Museum but this offer was declined, and after a failed venture as a picture dealer in London, d’Athanasi died in poverty in 1854, taking with him his knowledge of the site of the tomb.

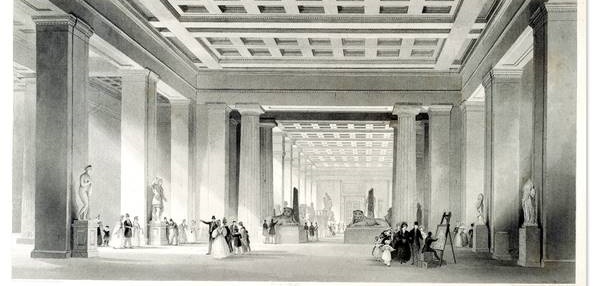

The Nebamun fragments formed part of a huge amount of Egyptian antiquities that poured into the British Museum in the 1820s and 1830s [8], prompting the setting up of the Egyptian Saloon, where the Nebamun fragments were first exhibited in 1835 (Fig 4). There they were described, rather slightingly, as “fresco paintings, chiefly illustrative of the domestic habits of the Egyptians” [9], and were presented as isolated fragments, with little or no context or indication that they all came a tomb, let alone from the same tomb.

Ten of the fragments taken by d’Athanasi were included in the first, huge, batch of collections that Henry Salt sent back to the British Museum [6]. After much haggling, the Museum settled for what Salt described as the “miserable sum” of £2,000, apparently not enough to even cover his expenditure [7]. After Salt died in 1827, d’Athanasi offered his services to the Museum but this offer was declined, and after a failed venture as a picture dealer in London, d’Athanasi died in poverty in 1854, taking with him his knowledge of the site of the tomb.

The Nebamun fragments formed part of a huge amount of Egyptian antiquities that poured into the British Museum in the 1820s and 1830s [8], prompting the setting up of the Egyptian Saloon, where the Nebamun fragments were first exhibited in 1835 (Fig 4). There they were described, rather slightingly, as “fresco paintings, chiefly illustrative of the domestic habits of the Egyptians” [9], and were presented as isolated fragments, with little or no context or indication that they all came a tomb, let alone from the same tomb.

Fig 4: The Grand Saloon and the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery, engraving The British Museum, London, England, mid to late 1830s. From Illustrations of the British Museum.

Originally, along with other Egyptian art, the Nebamun fragments were regarded as quaint antiquities, unlike the “fine art” of Greek or Roman antiquities. However, they are now recognised as some of the Museum’s greatest treasures. In the late 1990s, they underwent a period of major conservation, consolidation and analysis—a 7 year project that turned out to be the largest in the history of the Museum’s collections – and are now displayed in a way that appropriately reflects their tomb-wall origins (Fig 5).

Originally, along with other Egyptian art, the Nebamun fragments were regarded as quaint antiquities, unlike the “fine art” of Greek or Roman antiquities. However, they are now recognised as some of the Museum’s greatest treasures. In the late 1990s, they underwent a period of major conservation, consolidation and analysis—a 7 year project that turned out to be the largest in the history of the Museum’s collections – and are now displayed in a way that appropriately reflects their tomb-wall origins (Fig 5).

Fig 5: British Museum, Room 61, Nebamun Tomb-Chapel display

Pt 2: THE PAINTINGS

What the Nebamun paintings show

The paintings vividly depict the life and pursuits of Nebamun, an Egyptian official described as a “the scribe and grain-accountant of Amun”, the state-god of the period. Though this position sounds relatively lowly, it must be remembered that accurate records of grain stocks were vital in a country in which drought could have devastating consequences. Richard Parkinson notes that the temple complex where the god was worshipped, and where Nebamun worked, was a “hugely powerful institution”, and that Nebamun was probably best described as a chief middle manager, a person of considerable practical importance, well- to-do, though not of the highest rank [10].

|

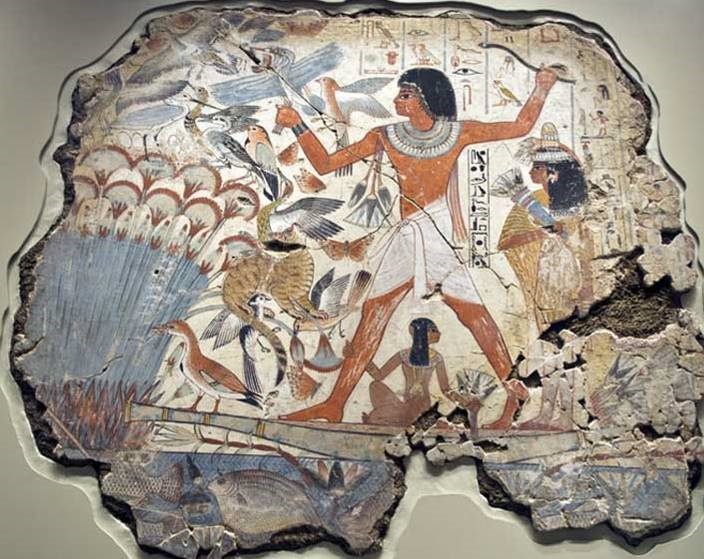

Despite the fact that the paintings were over 3,000 years old, they were (and still are) remarkably well preserved, due to the dryness of the air in the sealed underground tomb. Their fresh appearance, together with the general liveliness (raciness, even) of the scenes depicted, combine to present a remarkable effect of immediacy. This effect is enhanced by the fact that many of the scenes – the herding, the geese market and so on – could still be seen in Egypt today.

The paintings also exhibit a relatively sophisticated level of artistry, particularly evident in the hair, feathers and skin effects (see, for example, the animals and birds in Fig 6). This degree of skill is perhaps surprising for the tomb of a relatively middle-ranking official such as Nebamun. Parkinson has suggested that this may have occurred because the tomb was in the neighborhood of other higher ranking tombs, from which the artists may have been co-opted to help out with the Nebamun project. |

How they were created

------------------------------------------------------------------- The painting surface would have consisted of a thick layer of mud plaster, mixed with chopped straw applied to the wall of the rock-cut chambers of the tomb, and covered with a thin layer of white plaster. The paint was applied while the plaster was still setting, using the fresco technique [11]. Black pigments came from soot, red and yellow from ochre, white from a natural salt such as calcium sulphate, and blue or green from ground glass (“frit”) [see our article on Egyptian Blue]. Paintbrushes would have been made from chewed rushes. Parkinson suggests that the whole job would have been completed in three months [12]. -----------------------------------------------------------------. |

An idealised life

The paintings were intended to provide a link between Nebamun’s life and the way in which he would have wished to be commemorated by his family in death (the afterlife). Friends and family would have visited the painted upper part of the tomb, contemplate the paintings, leave gifts and hold feasts to commemorate his life.

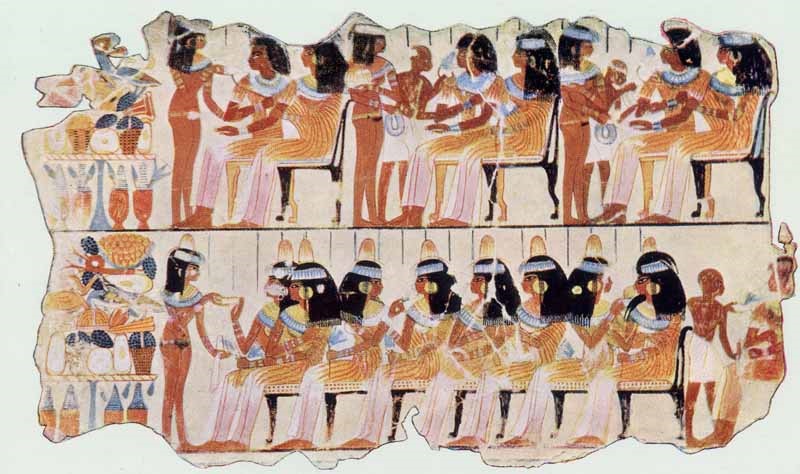

The surviving fragments depict a huge range of activities – the making of offerings, a large banquet, the produce of the estates, the extensive gardens, the bringing of offerings, and hunting in the marshes. While many everyday scenes are shown, many of the occasions, and Nebamun’s role in them, are significantly enhanced and idealised.

The surviving fragments depict a huge range of activities – the making of offerings, a large banquet, the produce of the estates, the extensive gardens, the bringing of offerings, and hunting in the marshes. While many everyday scenes are shown, many of the occasions, and Nebamun’s role in them, are significantly enhanced and idealised.

Fig 6: Marsh hunting scene, Nebamun tomb chapel c 1350 BC © British Museum http://www.ancient-egypt.co.uk/british%20museum/nebamun/

So, for example, in the marsh hunting scene (Fig 6), the vibrantly-coloured Nebamun stands on a papyrus skiff at the head of a hunting trip into reed-covered marshes. With his black wig and beaded collar, holding his snake-headed throwing stick, he strikes an athletic, dynamic, almost heroic pose, as master of the whole proceedings [13]. Reflecting his importance, he is shown towering above his respectful, expensively dressed wife Hatshepsut and his submissive daughter at his feet. Around him is an extravagant display of delicately depicted birds and butterflies, with a teeming variety of fish below. While heroic and idealised, the scene also captures some more homely details – his daughter holding affectionately on to his leg, or the cat grabbing one of the felled birds.

So, for example, in the marsh hunting scene (Fig 6), the vibrantly-coloured Nebamun stands on a papyrus skiff at the head of a hunting trip into reed-covered marshes. With his black wig and beaded collar, holding his snake-headed throwing stick, he strikes an athletic, dynamic, almost heroic pose, as master of the whole proceedings [13]. Reflecting his importance, he is shown towering above his respectful, expensively dressed wife Hatshepsut and his submissive daughter at his feet. Around him is an extravagant display of delicately depicted birds and butterflies, with a teeming variety of fish below. While heroic and idealised, the scene also captures some more homely details – his daughter holding affectionately on to his leg, or the cat grabbing one of the felled birds.

Pt 3: CENSORSHIP

We have already seen how the version of Nebamun’s life depicted by the original tomb painters was not intended to be realistic, but rather presented an ideal version of how Nebamun would have liked to be remembered. We have also seen how the selection of the particular paintings which have survived depended entirely on d’Athanasi’s often-idiosyncratic choice as to what was likely to be saleable in Europe; and that this resulted in many of the images being either destroyed as part of his exuberant “excavations” or lost – apparently forever – when the tomb was sealed.

So the identity and the contents of the paintings that we see today have already been preselected and preconditioned by cultural, artistic or personal choices made in the past. In fact, it seems that just about everyone who has had anything to do with the Nebamun tomb paintings has felt the need to put their own spin on them. One step in this process occurred not long after the tomb was completed. And, as we shall now see, it arose in a totally unexpected way.

The new art and iconoclasm of Akhenaten

During Nebamun’s lifetime, the state-god was Amun, the king of the gods, worshipped in a vast sacred complex that had been founded six centuries earlier. It was an age of prosperity and luxury. Thebes, with its population of 90,000 and its major temples, was regarded as a sacred place, a cosmic centre [14].

Radical change, however, was in store. When the new pharaoh Amenhotep IV came to power (1353- 1336 BC), he initiated a religious revolution, banning Amun and the lesser gods, and replacing them with a single god, Aten, the Sun God – thus achieving the distinction of creating a new, compulsory monotheistic religion. He built a temple to his new god at Karnak and moved his court to El-Armana. He changed his name to Akhenaten (meaning “Effective spirit of Aten”) and upset centuries of tradition by abandoning the official artistic practices and replacing them with a radical new style, named “Amarna” after the location of the new court (Fig 7) [15]

Radical change, however, was in store. When the new pharaoh Amenhotep IV came to power (1353- 1336 BC), he initiated a religious revolution, banning Amun and the lesser gods, and replacing them with a single god, Aten, the Sun God – thus achieving the distinction of creating a new, compulsory monotheistic religion. He built a temple to his new god at Karnak and moved his court to El-Armana. He changed his name to Akhenaten (meaning “Effective spirit of Aten”) and upset centuries of tradition by abandoning the official artistic practices and replacing them with a radical new style, named “Amarna” after the location of the new court (Fig 7) [15]

Fig 7: Akhenaten, his wife Nefertiti and their children, with rays of the sun disc, c 1340 BC (Wikimedia Commons).

If this new style of art seems dramatic even to our eyes, it must have appeared even more so to the ancient Egyptians. Akhenaten often had himself portrayed in a seemingly exaggerated, almost deformed way, with elongated features, a languorous body, thin legs and a curiously slack and distended stomach. Opinion seems divided on whether this was just an artistic style in the same way as Mannerist elongation, or whether it was a realistic representation of that Akhenaten looked like. If the latter, it seems possible that he was suffering from some sort of medical affliction In this notoriously problematic area of art-based diagnosis, some suggested possibilities are Froelich’s Syndrome, Klinefelter Syndrome or Marfan Syndrome, or a combination of conditions [16].

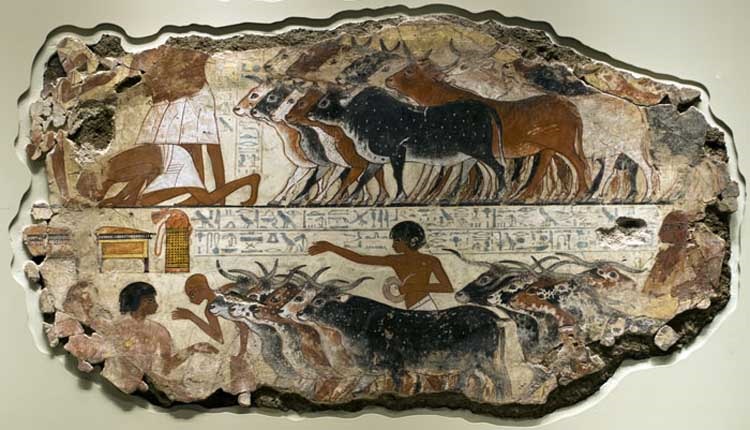

For our purposes, what is particularly significant about this radical change -- in both artistic style and religious affinity -- is that Akhenaten ordered that all references to Amun be hacked out on all monuments. This included Nebamun’s tomb, where the god’s name Amun has been systematically and roughly removed. This even applied to the “amun” part of Nebamun’s own name (which you'll remember meant “My lord is Amun”). These crude obliterations can still be seen, for example, in the far right of the lower panel of the cattle scene (Fig 8) and in the lower right of the marsh hunting scene (Fig 6). Even a ram’s head in one of the tomb’s agricultural scenes was hacked out, presumably because the ram was an animal closely associated with Amun [17].

If this new style of art seems dramatic even to our eyes, it must have appeared even more so to the ancient Egyptians. Akhenaten often had himself portrayed in a seemingly exaggerated, almost deformed way, with elongated features, a languorous body, thin legs and a curiously slack and distended stomach. Opinion seems divided on whether this was just an artistic style in the same way as Mannerist elongation, or whether it was a realistic representation of that Akhenaten looked like. If the latter, it seems possible that he was suffering from some sort of medical affliction In this notoriously problematic area of art-based diagnosis, some suggested possibilities are Froelich’s Syndrome, Klinefelter Syndrome or Marfan Syndrome, or a combination of conditions [16].

For our purposes, what is particularly significant about this radical change -- in both artistic style and religious affinity -- is that Akhenaten ordered that all references to Amun be hacked out on all monuments. This included Nebamun’s tomb, where the god’s name Amun has been systematically and roughly removed. This even applied to the “amun” part of Nebamun’s own name (which you'll remember meant “My lord is Amun”). These crude obliterations can still be seen, for example, in the far right of the lower panel of the cattle scene (Fig 8) and in the lower right of the marsh hunting scene (Fig 6). Even a ram’s head in one of the tomb’s agricultural scenes was hacked out, presumably because the ram was an animal closely associated with Amun [17].

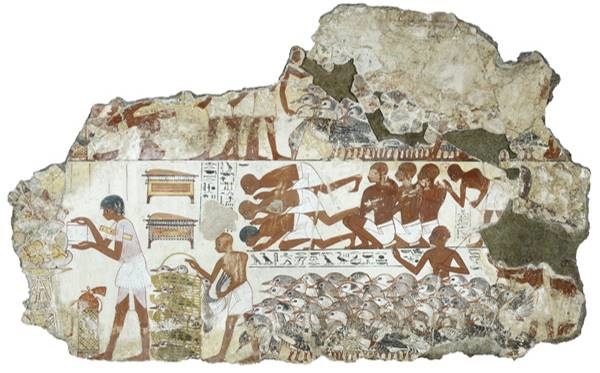

Fig 8: Cattle scene, Nebamun tomb-chapel c 1350 BC http://www.ancient-egypt.co.uk/british%20museum/nebamun/

The new style, however, did not long survive Akenaten himself. During the reign of the next Pharaoh, none other than the now-famous Tutankhamen, the old style was reinstated, and (rather clumsy) attempts were made to the Nebamun tomb to repair the gouged areas with patches of lime and plaster.

The new style, however, did not long survive Akenaten himself. During the reign of the next Pharaoh, none other than the now-famous Tutankhamen, the old style was reinstated, and (rather clumsy) attempts were made to the Nebamun tomb to repair the gouged areas with patches of lime and plaster.

Moral censorship

Thousands of years after the Akhenaten aberration, some of the Nebamun paintings would suffer yet another, very different, form of censorship. One of the alluring servant girls in the banquet scene was defaced [18], presumably in modern times, by having her pubic area – originally stippled black – deliberately and crudely gouged out (see Fig 13, servant girl at top left). And Parkinson records a similar “dramatic reaction against the naked female bodies” in photographs kept in an 1872 British Museum album. In the photo of Fig 9, the figures of the two near-naked dancing girls, with interlaced fingers, sinuously bending and stretching, have been erased altogether [19].

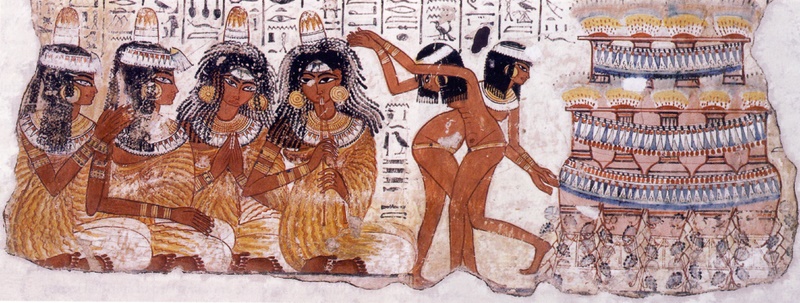

Fig 9: Banquet scene, musicians and dancing girls (detail): Nebamun Tomb-Chapel c 1350 BC

Pt 4: ADAPTATION BY MODERN ARTISTS

The display of the Nebamun paintings had a major impact on British ideas about ancient Egypt. The ancient but vibrant paintings proved to be a fertile source for depictions of Egyptian culture [20]. In the absence of actual evidence about how Egyptian houses were decorated, tomb paintings were co-opted to give an air of authenticity to paintings purporting to depict scenes from ancient Egyptian domestic or working life.

Alma-Tadema: where imagination and reality intersect

A good example is provided by Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s Joseph, Overseer of the Pharaoh’s Granary (Fig 10). In this painting, the Old Testament character Joseph, high-ranking chief adviser to the Egyptian pharaoh, is shown sitting imperiously in his raised chair, with his scribal assistant sitting cross-legged on the floor.

Fig 10: Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Joseph, Overseer of Pharoah’s Granaries (1874) Wikimedia Commons

Joseph, formerly a slave himself, had achieved his high position largely because of his ability to interpret dreams. In particular, his accurate interpretation of one of the Pharaoh’s dreams -- foreshadowing seven years of plenty followed by seven years of famine -- led to a nation-wide policy of grain storage, which, as it happened, enabled Egypt’s storehouses to feed the hungry during the lean years, thus confirming Joseph’s power and influence. In accordance with the Biblical story (Genesis 41), Alma-Tadema shows Joseph as wearing “robes of fine linen and…a gold chain around his neck” as symbols of his authority over the land of Egypt.

What is particularly interesting for our purposes is that on the wall panel behind Joseph, Alma-Tadema has directly copied a scene from the Nebamun tomb, which he of course would have seen in London. In this particular scene (Fig 11), flocks of geese that are being paraded for Nebamun’s inspection (he himself appears in a separate fragment). Parkinson describes the scribe standing at far left, with his pen container under his arm, as reading or presenting a scroll, with his kit bag at his feet. Behind him is a simply-dressed, bowing farmer holding a goose by its wings, and presenting baskets of birds with their beaks and webbed feet poking out. Behind and above him, three men kiss the earth in respect, and another three, shaven-headed to indicate their low rank, squat with respectful gestures. Behind them is a man with a stick who, according to the hieroglyphs in the cartouche beneath his elbow, is ordering them to. “Sit down and don’t speak!” In the lower panel, a gaggle of geese is being driven by their gooseherd towards Nebamun [21].

Joseph, formerly a slave himself, had achieved his high position largely because of his ability to interpret dreams. In particular, his accurate interpretation of one of the Pharaoh’s dreams -- foreshadowing seven years of plenty followed by seven years of famine -- led to a nation-wide policy of grain storage, which, as it happened, enabled Egypt’s storehouses to feed the hungry during the lean years, thus confirming Joseph’s power and influence. In accordance with the Biblical story (Genesis 41), Alma-Tadema shows Joseph as wearing “robes of fine linen and…a gold chain around his neck” as symbols of his authority over the land of Egypt.

What is particularly interesting for our purposes is that on the wall panel behind Joseph, Alma-Tadema has directly copied a scene from the Nebamun tomb, which he of course would have seen in London. In this particular scene (Fig 11), flocks of geese that are being paraded for Nebamun’s inspection (he himself appears in a separate fragment). Parkinson describes the scribe standing at far left, with his pen container under his arm, as reading or presenting a scroll, with his kit bag at his feet. Behind him is a simply-dressed, bowing farmer holding a goose by its wings, and presenting baskets of birds with their beaks and webbed feet poking out. Behind and above him, three men kiss the earth in respect, and another three, shaven-headed to indicate their low rank, squat with respectful gestures. Behind them is a man with a stick who, according to the hieroglyphs in the cartouche beneath his elbow, is ordering them to. “Sit down and don’t speak!” In the lower panel, a gaggle of geese is being driven by their gooseherd towards Nebamun [21].

Fig 11: Herding geese scene. Nebamun tomb-chapel c 1350 BC (British Museum)

As a painter who was fascinated with the material remains of the ancient world [22], Alma-Tadema’s aim was “to reveal an antiquity based on ancient sources rather than on modern fantasies and preconceptions” [23]. From his point of view, the Nebamun scene was not only decorative, but also appropriate, as there are a number of parallels between its subject matter and his own. Both the Nebamun scene and his painting reflect the importance placed on food production in the kingdom. Both prominently depict a scribe serving his master. The theme of grain was obviously relevant both to Nebamun (because of his job) and to Joseph (because it was a part of his job, and also because of its pivotal role in his rise to power). In addition, the Nebamun scene is recognisably “Egyptian”, adding the appearance of verisimilitude which Alma-Tadema strived to give to his work.

In some other ways, however, this appearance of authenticity is misleading. Alma-Tadema’s approach was to include archaeological details which were impressively realistic in themselves – often based on his extensive photographic collection (see our article on photography as a working aid) – but they were sometimes inappropriate in the particular context of what he was depicting. So, he might have altered their scale, their function, or their period to suit his purposes [24]. In this particular case, for example, he would not have been concerned that he was showing a piece of tomb art as the type of decoration that would appear in a work setting, such as Joseph’s. Nor was it relevant that the fragment, dating from about 1350 BC, was actually not created for centuries after Joseph is generally assumed to have died. In addition, Alma-Tadema has also expanded the physical width of the scene, so as to ensure that the scribe in the Nebamun panel is not hidden behind Joseph’s chair.

As a painter who was fascinated with the material remains of the ancient world [22], Alma-Tadema’s aim was “to reveal an antiquity based on ancient sources rather than on modern fantasies and preconceptions” [23]. From his point of view, the Nebamun scene was not only decorative, but also appropriate, as there are a number of parallels between its subject matter and his own. Both the Nebamun scene and his painting reflect the importance placed on food production in the kingdom. Both prominently depict a scribe serving his master. The theme of grain was obviously relevant both to Nebamun (because of his job) and to Joseph (because it was a part of his job, and also because of its pivotal role in his rise to power). In addition, the Nebamun scene is recognisably “Egyptian”, adding the appearance of verisimilitude which Alma-Tadema strived to give to his work.

In some other ways, however, this appearance of authenticity is misleading. Alma-Tadema’s approach was to include archaeological details which were impressively realistic in themselves – often based on his extensive photographic collection (see our article on photography as a working aid) – but they were sometimes inappropriate in the particular context of what he was depicting. So, he might have altered their scale, their function, or their period to suit his purposes [24]. In this particular case, for example, he would not have been concerned that he was showing a piece of tomb art as the type of decoration that would appear in a work setting, such as Joseph’s. Nor was it relevant that the fragment, dating from about 1350 BC, was actually not created for centuries after Joseph is generally assumed to have died. In addition, Alma-Tadema has also expanded the physical width of the scene, so as to ensure that the scribe in the Nebamun panel is not hidden behind Joseph’s chair.

Gauguin’s Ta Matete: Egyptian nobility and Tahitian prostitutes

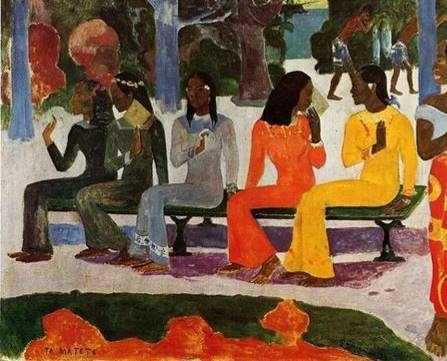

Fig 12: Paul Gauguin, Ta Matete (1892) www.paul-gauguin.net

The time difference between Alma-Tadema and Gauguin is less than a generation, but the gulf in style and intentions is vast. In this painting (Fig 12), far from trying to add a veneer of realism to his painting, Gauguin has used his familiarity with the Nebamun paintings to provide a deliberately anachronistic air to the work.

Ta Matete, meaning “To Market”, shows a group of Tahitian women sitting on a low park bench, conversing with each other, with the Pacific Ocean in the far background. At first glance, the painting is capable of being seen simply as a local Tahitian scene. However, the uniform sitting postures of the women and the odd positioning of their hands hint that something else is going on.

In fact, it appears that the painting was almost certainly based on the Nebamun tomb fragment depicting female guests at a banquet (lower panel in Fig 13) [25]. Gauguin was known for his interest in adapting primitive and archaic sources, and had seen this scene when he visited the Nebamun exhibition at the British Museum some years before, taking a photograph/postcard with him back to Tahiti [26].

The time difference between Alma-Tadema and Gauguin is less than a generation, but the gulf in style and intentions is vast. In this painting (Fig 12), far from trying to add a veneer of realism to his painting, Gauguin has used his familiarity with the Nebamun paintings to provide a deliberately anachronistic air to the work.

Ta Matete, meaning “To Market”, shows a group of Tahitian women sitting on a low park bench, conversing with each other, with the Pacific Ocean in the far background. At first glance, the painting is capable of being seen simply as a local Tahitian scene. However, the uniform sitting postures of the women and the odd positioning of their hands hint that something else is going on.

In fact, it appears that the painting was almost certainly based on the Nebamun tomb fragment depicting female guests at a banquet (lower panel in Fig 13) [25]. Gauguin was known for his interest in adapting primitive and archaic sources, and had seen this scene when he visited the Nebamun exhibition at the British Museum some years before, taking a photograph/postcard with him back to Tahiti [26].

Fig 13: Banqueting scene (detail), Nebamun Tomb Chapel c 1350 BC

Both the Nebamun scene and Gauguin’s share a frieze-like structure, with the sequence of seated female figures positioned evenly across the bench, an interplay of sharp profiles, clearly-defined figures, long robes, elongated fingers and stylised gestures. In particular, there is strong similarity in the positioning of the hands, especially the distinctive hand gesture of the seated woman at far left in both the Gauguin and the Nebamun works.

The title of Gauguin’s work refers to the market square in the capital Papeete. Belinda Thompson has described this as the nearest Tahitian equivalent to the night-life district of Pigalle, also known as the Meat Market) [27]. It appears that the Tahitian women depicted by Gauguin are actually prostitutes who would normally frequent the market, in response to the demands of the European males – in particular, visiting sailors, here suggested by the sailing boat at anchor that we can just about discern on the horizon in the background of the painting, between the trees. It has even been suggested that the rectangular cards held by two of the women are not decorative fans but, rather deflatingly, their official certificates declaring their freedom from venereal disease.

Gauguin had a rather sanguine view of prostitutes in Tahiti. In his book Before and After [28], he says that prostitution in Tahiti had none of the negative connotations it has in the West because sex in Tahiti was never considered immoral. Similarly, in Noa Noa, he commented admiringly that “the amorous passion of a Maori [Tahitian] courtesan is something quite different from the passivity of a Parisian cocotte – something very different! There is a fire in her blood, which calls forth love as its essential nourishment; which exhales it like a fatal perfume. These eyes and this mouth cannot lie. Whether calculating or not, it is always love that speaks from them” [29].

However, exactly what Gauguin was attempting to imply in this painting, if anything, is open to conjecture. The painting may possibly be a critical comment on the way in which the more Western style of prostitution was infiltrating local culture. If so, it would one of the few pictures in which Gauguin deals with the social realities of Tahitian life [30]. Alternatively, Gauguin may have been saying that the local Tahitian prostitutes had their own nobility, comparable to that of the high-born Egyptian women depicted in the Nebamun fragment. In this connection, it may also be relevant that, according to some anthropological theories current at the time, the mysterious Polynesian ethnic origins could be traced all the way back to ancient Egypt [31].

Both the Nebamun scene and Gauguin’s share a frieze-like structure, with the sequence of seated female figures positioned evenly across the bench, an interplay of sharp profiles, clearly-defined figures, long robes, elongated fingers and stylised gestures. In particular, there is strong similarity in the positioning of the hands, especially the distinctive hand gesture of the seated woman at far left in both the Gauguin and the Nebamun works.

The title of Gauguin’s work refers to the market square in the capital Papeete. Belinda Thompson has described this as the nearest Tahitian equivalent to the night-life district of Pigalle, also known as the Meat Market) [27]. It appears that the Tahitian women depicted by Gauguin are actually prostitutes who would normally frequent the market, in response to the demands of the European males – in particular, visiting sailors, here suggested by the sailing boat at anchor that we can just about discern on the horizon in the background of the painting, between the trees. It has even been suggested that the rectangular cards held by two of the women are not decorative fans but, rather deflatingly, their official certificates declaring their freedom from venereal disease.

Gauguin had a rather sanguine view of prostitutes in Tahiti. In his book Before and After [28], he says that prostitution in Tahiti had none of the negative connotations it has in the West because sex in Tahiti was never considered immoral. Similarly, in Noa Noa, he commented admiringly that “the amorous passion of a Maori [Tahitian] courtesan is something quite different from the passivity of a Parisian cocotte – something very different! There is a fire in her blood, which calls forth love as its essential nourishment; which exhales it like a fatal perfume. These eyes and this mouth cannot lie. Whether calculating or not, it is always love that speaks from them” [29].

However, exactly what Gauguin was attempting to imply in this painting, if anything, is open to conjecture. The painting may possibly be a critical comment on the way in which the more Western style of prostitution was infiltrating local culture. If so, it would one of the few pictures in which Gauguin deals with the social realities of Tahitian life [30]. Alternatively, Gauguin may have been saying that the local Tahitian prostitutes had their own nobility, comparable to that of the high-born Egyptian women depicted in the Nebamun fragment. In this connection, it may also be relevant that, according to some anthropological theories current at the time, the mysterious Polynesian ethnic origins could be traced all the way back to ancient Egypt [31].

Weguelin: a cat, a priestess and an offering

Nebamun scenes have appeared in a number of other artworks [32]. For example, Weguelin’s Obsequies of an Egyptian Cat (1886) depicts a funeral rite, with a priestess kneeling before an altar on which a mummified cat has been stood upright (Fig 14). The priestess is burning incense, and has presented the cat with offerings of flowers, food, and a saucer of milk.

Fig 14: John Reinhard Weguelin, Obsequies of an Egyptian Cat (1886), Wikimedia Commons

On the right side of the fresco on the wall in the background there is a more complete representation of the Nebamun “geese herding” fragment (see Fig 11), though this one is not partly obscured as in the Alma-Tadema’s work. On the left hand side of the fresco, Weguelin has also incorporated another Nebamun scene of men marching left to right. Although both scenes are joined as if they were part of the one frieze, this second scene is from a quite different Nebamun fragment, “the bringers of offerings”. In effect, Weguelin has brought two separate Nebamun scenes together on the basis that they can both be broadly related to his own subject matter.

On the right side of the fresco on the wall in the background there is a more complete representation of the Nebamun “geese herding” fragment (see Fig 11), though this one is not partly obscured as in the Alma-Tadema’s work. On the left hand side of the fresco, Weguelin has also incorporated another Nebamun scene of men marching left to right. Although both scenes are joined as if they were part of the one frieze, this second scene is from a quite different Nebamun fragment, “the bringers of offerings”. In effect, Weguelin has brought two separate Nebamun scenes together on the basis that they can both be broadly related to his own subject matter.

Conclusion

What we see today of the Nebamun tomb paintings is just fragmentary. The amount that was destroyed, lost or never even discovered in the first place, means that what we have left is largely a matter of luck or circumstance. This process is exacerbated the fact that, even with the pieces that have survived, they were commonly treated as fair game for anyone into whose hands they fell – whether it may be, as in the case of the Nebamun paintings, a fortune-seeking collector/looter, a government imposing political censorship or a modern day custodian imposing moral censorship.

Yet this story also illustrates the vitality of art, in the way that the Nebamun paintings have been re-used and adapted for a variety of artistic purposes. In these cases, there is no attempt to hide the origins of the paintings; indeed, their originality and perceived meaning is the very reason that they have been used, even if that meaning may sometimes have been somewhat distorted in the process.

© Philip McCouat, 2015

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Lost masterpieces of ancient Egyptian art from the Nebamun tomb-chapel”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

For more Journal articles on Egypt, see:

· Egyptian Blue: the colour of technology

· The Life and Death of Mummy Brown

· The Art of Giraffe Diplomacy

Return to HOME

Yet this story also illustrates the vitality of art, in the way that the Nebamun paintings have been re-used and adapted for a variety of artistic purposes. In these cases, there is no attempt to hide the origins of the paintings; indeed, their originality and perceived meaning is the very reason that they have been used, even if that meaning may sometimes have been somewhat distorted in the process.

© Philip McCouat, 2015

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Lost masterpieces of ancient Egyptian art from the Nebamun tomb-chapel”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

For more Journal articles on Egypt, see:

· Egyptian Blue: the colour of technology

· The Life and Death of Mummy Brown

· The Art of Giraffe Diplomacy

Return to HOME

End notes

1 Richard Parkinson, The Painted Tomb-Chapel of Nebamun, The British Museum Press, London, 2008 at 10. This part of the article is largely based on Parkinson’s detailed and authoritative work.

2 See our articles The Life and Death of Mummy Brown and The Art of Giraffe Diplomacy.

3 Originally known as Demetrio Papandriopulo. He excavated on Salt’s behalf at Thebes from 1817 to 1827, and later on his own behalf: https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=98025

4 Parkinson, op cit at 27ff.

5 Parkinson, op cit at 32.

6 An eleventh fragment was evidently sold in Egypt to other collectors and was later presented to the Museum. Other smaller fragments found their way to other museums, such as the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, and possibly the Cairo Museum.

7 Parkinson, op cit at 11, citing D Manley and P Rée, Henry Salt: Artist, Traveller, Diplomat, Egyptologist, London, Libri 2002 at 203.

8 Parkinson, op cit at 17.

9 Parkinson, op cit at 18.

10.Parkinson, op cit at 39ff.

11.Parkinson, op cit at 47ff.

12. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/jan/04/british-museum-egyptian-nebamun-tomb

13. Parkinson, op cit at 122ff; http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/jan/04/british-museum-egyptian-nebamun-tomb

14. Parkinson, op cit at 39-41.

15. “Amarna Period”, Society for the Promotion of the Egyptian Museum Berlin http://www.egyptian-museum-berlin.com/c52.php. For an unusually favourable view of Akhenaten’s life and achievements, see Jacquetta Hawkes, Man and the Sun, The Cresset Press 1962, at 108ff.

16. See, for example, A Burridge, “Did Akhenaten Suffer from Marfan’s Syndrome?” Akhenaten Temple Project Newsletter, No 3 Sept 1995; and “A Feminine Physique, A Long, Thin Neck and Elongated Head Suggest Pharaoh Akhenaten Had Two Rare Disorders” (University of Maryland Medical Center)

17. Parkinson, op cit at 39, 43, 127.

18. Parkinson, op cit at 86.

19. Parkinson, op cit at 20.

20. Parkinson, op cit at 18, citing S Moser, Wondrous Curiosities: Ancient Egypt at the British Museum, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2006.

21. Parkinson, op cit at 97.

22. E. Prettejohn, “Antiquity fragmented and reconstructed: Alma-Tadema’s compositions,” in Edwin Becker et al (eds), Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, New York, 1997, at 42.

23. Rosemary J Barrow, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Phaedon, 2003, at 27.

24. Prettejohn, op cit at 33ff.

25. A fragment of the banqueting scene also appears in Edward Long’s An Egyptian Feast (1877), on the right side of the lower frieze on the wall in the background.

26. Belinda Thompson, Gauguin, Thames and Hudson, London, 1987, at 151-4.

27. Thompson, op cit at 151.

28. Paul Gauguin, Before and After, 1923.

29. Paul Gauguin, Noa, Noa, 1919 at 20.

30. Thompson, op cit at 154.

31. Thompson, op cit at 154.

32. See also note 25.

© Philip McCouat, 2015

Return to HOME

2 See our articles The Life and Death of Mummy Brown and The Art of Giraffe Diplomacy.

3 Originally known as Demetrio Papandriopulo. He excavated on Salt’s behalf at Thebes from 1817 to 1827, and later on his own behalf: https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=98025

4 Parkinson, op cit at 27ff.

5 Parkinson, op cit at 32.

6 An eleventh fragment was evidently sold in Egypt to other collectors and was later presented to the Museum. Other smaller fragments found their way to other museums, such as the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, and possibly the Cairo Museum.

7 Parkinson, op cit at 11, citing D Manley and P Rée, Henry Salt: Artist, Traveller, Diplomat, Egyptologist, London, Libri 2002 at 203.

8 Parkinson, op cit at 17.

9 Parkinson, op cit at 18.

10.Parkinson, op cit at 39ff.

11.Parkinson, op cit at 47ff.

12. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/jan/04/british-museum-egyptian-nebamun-tomb

13. Parkinson, op cit at 122ff; http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/jan/04/british-museum-egyptian-nebamun-tomb

14. Parkinson, op cit at 39-41.

15. “Amarna Period”, Society for the Promotion of the Egyptian Museum Berlin http://www.egyptian-museum-berlin.com/c52.php. For an unusually favourable view of Akhenaten’s life and achievements, see Jacquetta Hawkes, Man and the Sun, The Cresset Press 1962, at 108ff.

16. See, for example, A Burridge, “Did Akhenaten Suffer from Marfan’s Syndrome?” Akhenaten Temple Project Newsletter, No 3 Sept 1995; and “A Feminine Physique, A Long, Thin Neck and Elongated Head Suggest Pharaoh Akhenaten Had Two Rare Disorders” (University of Maryland Medical Center)

17. Parkinson, op cit at 39, 43, 127.

18. Parkinson, op cit at 86.

19. Parkinson, op cit at 20.

20. Parkinson, op cit at 18, citing S Moser, Wondrous Curiosities: Ancient Egypt at the British Museum, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2006.

21. Parkinson, op cit at 97.

22. E. Prettejohn, “Antiquity fragmented and reconstructed: Alma-Tadema’s compositions,” in Edwin Becker et al (eds), Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, New York, 1997, at 42.

23. Rosemary J Barrow, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Phaedon, 2003, at 27.

24. Prettejohn, op cit at 33ff.

25. A fragment of the banqueting scene also appears in Edward Long’s An Egyptian Feast (1877), on the right side of the lower frieze on the wall in the background.

26. Belinda Thompson, Gauguin, Thames and Hudson, London, 1987, at 151-4.

27. Thompson, op cit at 151.

28. Paul Gauguin, Before and After, 1923.

29. Paul Gauguin, Noa, Noa, 1919 at 20.

30. Thompson, op cit at 154.

31. Thompson, op cit at 154.

32. See also note 25.

© Philip McCouat, 2015

Return to HOME