The Sphinx of Delft

Jan Vermeer’s demise and rediscovery

By Philip McCouat For comments on this article see here

Introduction

Today, the 17th century Dutch artist Jan Vermeer [1] is one of the more famous and recognisable painters in the Western world.

His beautifully-composed, meticulously-detailed domestic interiors, typically with only one or two characters, and with light streaming in through a window, have struck a chord with modern audiences. These quietly atmospheric paintings seem to give viewers the impression that they are witnessing or interrupting a private moment, and invite them to imagine their own back story for what may be happening.

However, Vermeer has not always been famous, or widely admired. The often-told story of his calamitous fall from grace, the two centuries in which he was virtually forgotten, the apparently sudden rehabilitation of his reputation and the sensational large-scale forging of his works, have taken a powerful hold on our collective imaginations. But questions remain. How did it happen that he was “forgotten”? Why is it that he was suddenly “rediscovered”? Why was his forger able to get away with such palpable fakes? And why is Vermeer now so revered?

In this article, we attempt to give some answers to these questions.

His beautifully-composed, meticulously-detailed domestic interiors, typically with only one or two characters, and with light streaming in through a window, have struck a chord with modern audiences. These quietly atmospheric paintings seem to give viewers the impression that they are witnessing or interrupting a private moment, and invite them to imagine their own back story for what may be happening.

However, Vermeer has not always been famous, or widely admired. The often-told story of his calamitous fall from grace, the two centuries in which he was virtually forgotten, the apparently sudden rehabilitation of his reputation and the sensational large-scale forging of his works, have taken a powerful hold on our collective imaginations. But questions remain. How did it happen that he was “forgotten”? Why is it that he was suddenly “rediscovered”? Why was his forger able to get away with such palpable fakes? And why is Vermeer now so revered?

In this article, we attempt to give some answers to these questions.

Vermeer’s early reputation

For most of his career, Vermeer was regarded as a well-respected and talented artist/art dealer in his hometown Delft, in Holland. His works, although relatively few in number, brought very good prices, though artists such as Gerard Dou and Frans van Mieris were more expensive [2]. Reflecting his status, he was elected twice to the post of the Headman of his Guild, and was regarded as a natural successor to the prominent artist Carl Fabritus, who had been at the height of his powers when he was tragically killed in an explosion. Vermeer was described at the time as treading “masterfully” in his path [3].

However, a number of factors -- some historical, some personal and some fortuitous – came together to prompt a rather dramatic sudden decline in this healthy reputation. The main change was that in 1672, Holland, after going through a boom period, experienced a major decline in its economic fortunes. This decline, sparked by an invasion by the foreign troops of Louis XIV of France, was also reflected in its art market -- this had previously been very strong, enjoying a so-called “Golden Age”, but for various reasons, it was also particularly vulnerable [4]. One of the reasons for this was that in Holland there were no religious commissions, as the reformed churches remained strictly unadorned, without images [5]. Nor was there an established nobility prepared to regularly commission works to bolster their status, or for the common good. This meant that, with some exceptions, there were few large-scale commissions to keep artists in business.

In the private sector too, where Vermeer mainly operated, the Dutch war tactic of defending the country by flooding it created particular problems, as it destroyed the livelihoods of the tenant farmers, who became unable to pay their rent. This in turn damaged the fortunes of previously well-off individuals who would be the prime candidates to purchase individual artworks.

The result of all this was that for some time before his death, Vermeer, like many other local artists in a competitive market, found himself unable to find reliable purchasers, either for his own paintings or for those which he held as a dealer. In truth, even at the best of times, his financial position had been rather delicate. His large family – eleven of his children survived infancy – imposed huge demands on his cash flow, and at times he’d had to rely on getting financial support from his wife’s Catharina’s mother [6]. The fact that he was a slow and meticulous worker, sometimes producing only two or three paintings each year, and that he used expensive pigments (such as lapis lazuli) so lavishly, also meant that every failure to sell a work became a major reverse. The position was not helped by the need for him to retain a painting such as The Art of Painting as a permanent studio showpiece that showed off his talent.

The dire situation was further magnified by the fact that Vermeer’s reduced circumstances had also forced him to move with his family to smaller, less salubrious premises. He therefore found himself deprived of the familiar domestic environment which had proved such a fertile source of the settings and props that were used for many of his works. His output slowed to a trickle. According to Catharina, factors such as these pushed him into the “decay and decadence” that hastened him to an early death at the age of just 43 [7].

In the private sector too, where Vermeer mainly operated, the Dutch war tactic of defending the country by flooding it created particular problems, as it destroyed the livelihoods of the tenant farmers, who became unable to pay their rent. This in turn damaged the fortunes of previously well-off individuals who would be the prime candidates to purchase individual artworks.

The result of all this was that for some time before his death, Vermeer, like many other local artists in a competitive market, found himself unable to find reliable purchasers, either for his own paintings or for those which he held as a dealer. In truth, even at the best of times, his financial position had been rather delicate. His large family – eleven of his children survived infancy – imposed huge demands on his cash flow, and at times he’d had to rely on getting financial support from his wife’s Catharina’s mother [6]. The fact that he was a slow and meticulous worker, sometimes producing only two or three paintings each year, and that he used expensive pigments (such as lapis lazuli) so lavishly, also meant that every failure to sell a work became a major reverse. The position was not helped by the need for him to retain a painting such as The Art of Painting as a permanent studio showpiece that showed off his talent.

The dire situation was further magnified by the fact that Vermeer’s reduced circumstances had also forced him to move with his family to smaller, less salubrious premises. He therefore found himself deprived of the familiar domestic environment which had proved such a fertile source of the settings and props that were used for many of his works. His output slowed to a trickle. According to Catharina, factors such as these pushed him into the “decay and decadence” that hastened him to an early death at the age of just 43 [7].

The decline accelerates

The decline in Vermeer’s reputation during the last period of his life sharpened further after his death. His reputation was essentially local, without wider national or international exposure, and he had no pupils to carry on his tradition. Most of his purchasers, including his main supporter [8], were not only based in Delft, but had hung the works in their private homes, rather than having the works on public display. Furthermore, the value became of his works further depreciated when the newly-widowed Catharina, desperate to keep her family afloat, was forced to sell off whatever stock remained, sometimes at low prices.

Confusion about attributions of particular works also arose. Vermeer did not sign all his paintings, and when he did, managed to do so in half a dozen different ways. This created difficulties, especially as there were two other Dutch painters with the name “Jan Vermeer” [9]. Some of his works were also in poor condition, or were “improved” by overpainting, or deliberately misattributed to other more fashionable artists such as Gabriel Metsu or Pieter de Hooch [10]. For example, the painting of Cupid that originally appeared on the wall in Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (1670) was overpainted, possibly to make it look more fashionable for sale [11]. This issue of misattribution of Vermeer’s works, much to the detriment of his reputation, would continue for centuries, and has survived until modern times. Even today, estimates of the number of “known” Vermeers by even the most respected authorities vary widely, ranging from 29 to 36 [12].

In view of all these developments, it is perhaps not surprising that Vermeer’s career and works fell from public notice rather quickly. Eighteenth century texts on Dutch painting tended to largely ignore him. He was hardly mentioned in Houraken’s comprehensive 17th century source book [13] and, even in the 19th century, Vermeer was not mentioned in Sarah K Bolton’s Famous Artists. Seemingly inevitably, he became relegated to being just one of the many capable 17th century Dutch artists who were highly proficient in still lifes and domestic scenes, and who regularly borrowed ideas, inspiration, compositions and models from each other [14].

In view of all these developments, it is perhaps not surprising that Vermeer’s career and works fell from public notice rather quickly. Eighteenth century texts on Dutch painting tended to largely ignore him. He was hardly mentioned in Houraken’s comprehensive 17th century source book [13] and, even in the 19th century, Vermeer was not mentioned in Sarah K Bolton’s Famous Artists. Seemingly inevitably, he became relegated to being just one of the many capable 17th century Dutch artists who were highly proficient in still lifes and domestic scenes, and who regularly borrowed ideas, inspiration, compositions and models from each other [14].

Rediscovery: the art lover Thoré-Bürger

Vermeer’s public decline, however, did not mean that he was totally forgotten. Among some connoisseurs there still remained recognition of his talent and former reputation. Scattered but generally favourable mentions of him started surfacing in the late 18th century, a century after his death. In 1792, Jean Baptiste Lebrun [15] referred perceptively to “the van der Meer the historians have ignored… [H]e is a very great painter in the manner of Gabriel Metsu. His works are few and are better known and appreciated in Holland than anywhere else… It seems that he was particularly keen on sunlit effects, at which he was extremely successful” [16]. In 1816 a critic described him as “the Titian of the modern painters of the Dutch school” and in 1843 a reference was made to a “magnificent example” of his painting [17]. During the 18th century, there were also occasional significant sales of his works by astute buyers – in 1719 The Milkmaid was sold (cheaply); in 1710 four Vermeers were acquired by prestigious buyers; and in 1795 The Astronomer and The Geographer changed hands.

In addition, in the 19th century, thanks to the art historian Gustav Waagen, Vermeer was belatedly credited with The Art of Painting (1666), after it had been previously attributed to Pieter de Hooch [18]. This was a positive sign, but more was to come as a result of the efforts of the 19th century journalist and art critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger. He became passionately interested in Vermeer’s work in the 1860s, likening it to that of the modernists Courbet and Manet in reflecting the everyday existence of ordinary folk [19]. He marvelled that so little was known about such a talented artist, whom he dubbed the mysterious “Sphinx of Delft”.

Thoré-Bürger set himself the task of correcting this artistic injustice by conducting a concerted campaign to restore Vermeer’s reputation by collecting and publishing information about him, and buying up his paintings whenever he could. Crucially, his researches also revealed the existence of a sales catalogue that had been prepared for the sale of many of Vermeer’s works just after his death, which greatly assisted in his search. Finally, in 1866, his years of diligent research resulted in the compilation of exhaustive catalogue of “known” works by Vermeer (which actually included some that actually weren’t Vermeers and some that have never been traced). Despite its errors, this monumental work was the start-point for the modern knowledge of Vermeer’s output.

Thoré-Bürger set himself the task of correcting this artistic injustice by conducting a concerted campaign to restore Vermeer’s reputation by collecting and publishing information about him, and buying up his paintings whenever he could. Crucially, his researches also revealed the existence of a sales catalogue that had been prepared for the sale of many of Vermeer’s works just after his death, which greatly assisted in his search. Finally, in 1866, his years of diligent research resulted in the compilation of exhaustive catalogue of “known” works by Vermeer (which actually included some that actually weren’t Vermeers and some that have never been traced). Despite its errors, this monumental work was the start-point for the modern knowledge of Vermeer’s output.

The Vermeer craze

Vermeer, now becoming recognised again, proved to be sensationally popular. Fortunately, as it happened, many of Vermeer’s artistic concerns coincided with trends in current taste -- the fascination with photography-inspired realism, his emphasis on the importance of natural light, and his choice of naturalistic everyday life rather than glorified subject matter appealed particularly to modern painters such as Renoir, Monet and van Gogh. Renoir for example declared The Lacemaker to be among the most beautiful works ever painted. Monet considered him to be a precursor to his own work. Van Gogh expressed fascination with "this strange painter's" technique and use of colour [19A].

Vermeer began to acquire a quasi-cult status. A mini-industry developed in Vermeer ephemera, gadgets and posters, and a sort of frenzy developed for his works [20]. The public were fascinated by his romantic back story – the allure of long-forgotten genius – and by the intriguingly quiet ambiguity of his paintings. The passionate art collector Andrew Mellon started paying exorbitant prices for some mediocre or even doubtful Vermeers. Everybody, it seemed, loved Vermeer. And his new-found fame was about to experience yet another major boost, this time from a very unexpected source.

Vermeer began to acquire a quasi-cult status. A mini-industry developed in Vermeer ephemera, gadgets and posters, and a sort of frenzy developed for his works [20]. The public were fascinated by his romantic back story – the allure of long-forgotten genius – and by the intriguingly quiet ambiguity of his paintings. The passionate art collector Andrew Mellon started paying exorbitant prices for some mediocre or even doubtful Vermeers. Everybody, it seemed, loved Vermeer. And his new-found fame was about to experience yet another major boost, this time from a very unexpected source.

Exploitation: the opportunist Han van Meegeren

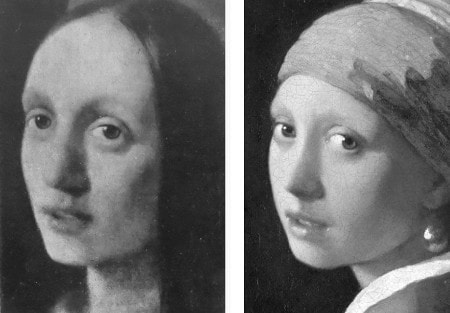

A good part of the interest in Vermeer arose from the fact of his “mystery” – how was it that we knew so little about his private life? How was it that such talented work could have been “forgotten”? And, most crucially, were there other Vermeers were simply waiting to be discovered? The hunt was on, and one of the main likely areas was in Vermeer’s early works. These works, few as they are, are rather different from the Vermeers that most people are familiar with – they are on religious themes, with looser brush strokes and indistinct backgrounds (Fig 4). So different, in fact, that their attribution to Vermeer is still not unanimously accepted [21].

All of these factors, combined with the high prices that started to be achieved for Vermeer’s works, would combine to make Vermeer an irresistible temptation for one group in particular – forgers. The most notable of these was the Dutch artist Han van Meegeren. He emerged in the 1930s, by which stage he had achieved a modest market for his legitimate works but, in his own mind, had never received enough recognition of his genius by the critics [22]. Moreover, and possibly more importantly, he had not earned the riches that he so desired. Aggrieved by this, he resolved to demonstrate his talent by creating a painting by a great master that all the critics would accept as genuine, and which he could sell at great profit. But which great master should he choose?

He was particularly attracted to the possibilities of the newly-popular Vermeer. He knew that little was known about Vermeer’s life, that there had been constant difficulties in attribution of the artist’s work, and that many art historians were convinced that there were more Vermeers out there. He intuited that a new painting, ostensibly from Vermeer’s misty early years, would have a ready-made receptive audience. In effect, he decided to give them what they wanted.

He was particularly attracted to the possibilities of the newly-popular Vermeer. He knew that little was known about Vermeer’s life, that there had been constant difficulties in attribution of the artist’s work, and that many art historians were convinced that there were more Vermeers out there. He intuited that a new painting, ostensibly from Vermeer’s misty early years, would have a ready-made receptive audience. In effect, he decided to give them what they wanted.

The forgery and its reception

It was no small task that van Meegeren set himself, and it took some years of research and experimentation to create a convincing version of a 17th century painting, in a style and with content that could plausibly be presented as a Vermeer, and to a level that would satisfy searching examination. The ultimate result was his Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus (Fig 5). Meegeren also concocted a plausible back story for it, according to which he had acquired it from an old family, who had held the painting, which lay forgotten and unrecognised for centuries in their ancestral castle.

It is true that this work would leave most modern viewers rather unimpressed. This is partly because it looks nothing like what we now regard as a typical Vermeer, representing as it does a youthful work in a style, and with a subject matter, that Vermeer soon moved away from. But for many critics in the 1930s (now almost a century ago), it was treated as a work of genius. Dr Abraham Bredius, the most distinguished Dutch art expert in the early 20th century, was the first to be asked to examine it, and “was overwhelmed from the very moment he saw the very type of painting he predicted would surface”[23]. He excitedly authenticated it, not only as a masterpiece Vermeer, but as the masterpiece of Vermeer. This set the tone for many other patriotic Dutch critics to follow [24]. One noted that the face of Christ was “infinitely pathetic, and benign”, and a Dutch museum director wrote that the serving maid in Emmaus had the most beautiful face ever painted by Vermeer.

In fact, van Meegeren had been quite skilful in basing the modelling of his characters and use of colours used in Vermeer’s Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (Fig 4), and borrowing selectively from Vermeer’s later works to add verisimilitude (Vermeer himself often repeated details appearing in his works, for example, the image of Cupid in Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window; or the wall maps in The Art of Painting and many other works). So, for example, on the wine pitcher van Meegeren used the points of light that had been used by Vermeer in paintings such as The Music Lesson. In his later forged Last Supper, the face of St John would be a direct copy of the face of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, painted 250 years before.

In fact, van Meegeren had been quite skilful in basing the modelling of his characters and use of colours used in Vermeer’s Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (Fig 4), and borrowing selectively from Vermeer’s later works to add verisimilitude (Vermeer himself often repeated details appearing in his works, for example, the image of Cupid in Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window; or the wall maps in The Art of Painting and many other works). So, for example, on the wine pitcher van Meegeren used the points of light that had been used by Vermeer in paintings such as The Music Lesson. In his later forged Last Supper, the face of St John would be a direct copy of the face of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, painted 250 years before.

So the painting initially passed muster, and was eagerly purchased by a Rotterdam Museum for $268,000 [25], of which van Meegeren collected two-thirds. Over the next few years, as World War II wore on, van Meegeren would go on to produce five more forged Vermeers, and two Pieter de Hoochs. The War actually acted in van Meegeren’s favour -- sales of valuable paintings in Europe during these years tended to be conducted in secrecy, conveniently masking the fact that a suspiciously large number of Vermeers were suddenly being “discovered”. During the war, international dissemination of scholarly views, especially some extremely sceptical opinions from foreign countries, was also quite limited. So van Meegeren’s secret career prospered, particularly inside Holland, and he became a very rich man indeed.

Trial and revelation

When the crunch came, it came about in an unlikely and sensational way. One of his forged Vermeers, Christ and the Adultress, had been acquired during the war by the head of the German Nazi Party, the obsessive art collector Herman Goering [26]. After its post-war recovery, it was returned to Holland where questions were raised about how it had left there in the first place. Suddenly Van Meegeren found himself charged with treasonable collaboration with the enemy, for his role in selling a Dutch “National Treasure” to the Nazis.

After a few weeks in detention, van Meegeren finally realised he could not defeat the charge and its serious penalty unless he confessed to the much lesser offence of forging the painting. After all, it was the lack of recognition of his cleverness that was a part of the reason why he started his forgery career in the first place. But the problem was, of course, that he now had to prove it.

His bombshell confession prompted a full-on, exhaustive scientific examination of the painting, the first time this had actually been done. And bit by bit, the evidence mounted that the painting really was a fake, embarrassing as this was to the critics who had originally lauded it. Van Meegeren also offered to paint another “Vermeer” in his police cell to prove his forgery credentials, and actually started work on this, but stopped as soon as he was informed that he would only be charged with forgery, not collaboration.

His sensational trial, after two years preparation, was over in a day. Van Meegeren, fraudster to the end, tried to downplay his more venal motives of making money, and presented himself as a wily patriot who had not only exposed the established art critics to ridicule, but also succeeded in playing an elaborate trick on the Nazis [27]. He was, however, convicted and sentenced to a year’s jail, but he would never serve it – he died of a heart attack just a few weeks later.

After a few weeks in detention, van Meegeren finally realised he could not defeat the charge and its serious penalty unless he confessed to the much lesser offence of forging the painting. After all, it was the lack of recognition of his cleverness that was a part of the reason why he started his forgery career in the first place. But the problem was, of course, that he now had to prove it.

His bombshell confession prompted a full-on, exhaustive scientific examination of the painting, the first time this had actually been done. And bit by bit, the evidence mounted that the painting really was a fake, embarrassing as this was to the critics who had originally lauded it. Van Meegeren also offered to paint another “Vermeer” in his police cell to prove his forgery credentials, and actually started work on this, but stopped as soon as he was informed that he would only be charged with forgery, not collaboration.

His sensational trial, after two years preparation, was over in a day. Van Meegeren, fraudster to the end, tried to downplay his more venal motives of making money, and presented himself as a wily patriot who had not only exposed the established art critics to ridicule, but also succeeded in playing an elaborate trick on the Nazis [27]. He was, however, convicted and sentenced to a year’s jail, but he would never serve it – he died of a heart attack just a few weeks later.

Entry into popular culture

Nowadays, Vermeer has entered deep into popular Western culture. There are countless books in which he plays a role, including Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, Tracey Chevalier’s fiction bestseller Girl with a Pearl Earring and historian Timothy Brooks Vermeer’s Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World. His work has been celebrated in music (including an opera) and films (including a version of Chevalier’s book). In 1973, his Milkmaid was even adopted as an advertising logo for the Nestlé group (Fig 9). And most recently, the British artist David Hockney has ignited yet another major controversy over Vermeer’s supposed use of optical devices to achieve the reality of his images [28].

Conclusion

Vermeer’s story is instructive in a number of ways. Given his particular circumstances, we should perhaps not be overly surprised that he tended to be largely forgotten after his death. Long-lasting fame is likely to be elusive for an artist like Vermeer, who died young, had a limited output, a narrow market and multiple attribution issues, and was not seen as outrageously different from his or her peers.

Fortunately, for the sake of his reputation, Vermeer belatedly had a number of unusual factors that would work in his favour – he had an extraordinarily diligent champion; his work re-emerged in an era in which his style of art struck a responsive chord; and his work became the subject of a major international scandal over the forgery. We can all be grateful for his new-found artistic and cultural fame, but it was in no way inevitable.

We can also learn that experts can be surprisingly gullible when assessing new discoveries that tend to confirm their own pet theories. Just like the English palaeontologists who disastrously hailed the local discovery of Piltdown Man as the long-awaited “missing link”, the local art experts who initially celebrated van Meegeren’s work appear to have been inordinately influenced by the fact that it filled in the very gap that the experts had predicted ■

© Philip McCouat 2020, 2021, 2022

First published April 2020

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “The Sphinx of Delft: Jan Vermeer’s demise and rediscovery” Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com (2020)

RETURN TO HOME

Fortunately, for the sake of his reputation, Vermeer belatedly had a number of unusual factors that would work in his favour – he had an extraordinarily diligent champion; his work re-emerged in an era in which his style of art struck a responsive chord; and his work became the subject of a major international scandal over the forgery. We can all be grateful for his new-found artistic and cultural fame, but it was in no way inevitable.

We can also learn that experts can be surprisingly gullible when assessing new discoveries that tend to confirm their own pet theories. Just like the English palaeontologists who disastrously hailed the local discovery of Piltdown Man as the long-awaited “missing link”, the local art experts who initially celebrated van Meegeren’s work appear to have been inordinately influenced by the fact that it filled in the very gap that the experts had predicted ■

© Philip McCouat 2020, 2021, 2022

First published April 2020

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “The Sphinx of Delft: Jan Vermeer’s demise and rediscovery” Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com (2020)

RETURN TO HOME

End Notes

[1] 1632 – 1675

[2] Adriaan E Waiboer et al, Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting (Exh Cat), Yale University Press, New Haven 2017 at 87

[3] Jane Jelley, Traces of Vermeer, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2017 at 226

[4] Renzo Villa, Vermeer: The Complete Works, Silvana Editoriale, Milan 2012 at 7; Jelley, op cit at 13

[5] Villa, op cit at 7

[6] Jelley, op cit at 15

[7] Pierre Cabanne, Vermeer, Editions Terrail, Paris 2004 (transl John Tittensor) at 235

[8] His friend, the wealthy collector Pieter van Ruijven

[9] One in Haarlem, the other in Utrecht.

[10] Hans Koningsberger, The World of Vermeer 1632-1675, Time-Life International (Nederland), 1967 at 170

[11] Catherine Hickey, 7 May 2019 at https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/hidden-cupid-resurfaces-in-one-of-vermeer-s-best-known-works

[12] Koningsberger, op cit at 169. Some works, such as Girl with a Flute, are disputed

[13] Grand Theatre of Dutch Painters and Women Artists

[14] Waiboer, op cit at at 3

[15] Husband of the artist Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun

[16] Cabanne, op cit at 243

[17] Cabanne, op cit at 243

[18] Villa, op cit at 8

[19] Cabanne, op cit at 247

[19A] Letter to Emile Bernard 29/7/1888

[20] Villa, op cit at 10

[21] Koningsberger, op cit at 125

[22] Koningsberger, op cit at 171

[23] Thomas Hoving, False Impressions: The Hunt for Big-time Art Fakes, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1996 at 175

[24] One notable exception was John Huizinga, who said that the work was “lacking in soul and only playing with colours”

[25] Equivalent to about $5 million today

[26] Hoving, op cit at 176

[27] Hoving, op cit at 178

[28] David Hockney, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, 2001; David Steadman: Vermeer’s Camera: Uncovering the Truth behind the Masterpieces, 2001; Tim Jenison, Tim’s Vermeer (documentary film) 2013

© Philip McCouat 2020, 2021, 2022

RETURN TO HOME

[2] Adriaan E Waiboer et al, Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting (Exh Cat), Yale University Press, New Haven 2017 at 87

[3] Jane Jelley, Traces of Vermeer, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2017 at 226

[4] Renzo Villa, Vermeer: The Complete Works, Silvana Editoriale, Milan 2012 at 7; Jelley, op cit at 13

[5] Villa, op cit at 7

[6] Jelley, op cit at 15

[7] Pierre Cabanne, Vermeer, Editions Terrail, Paris 2004 (transl John Tittensor) at 235

[8] His friend, the wealthy collector Pieter van Ruijven

[9] One in Haarlem, the other in Utrecht.

[10] Hans Koningsberger, The World of Vermeer 1632-1675, Time-Life International (Nederland), 1967 at 170

[11] Catherine Hickey, 7 May 2019 at https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/hidden-cupid-resurfaces-in-one-of-vermeer-s-best-known-works

[12] Koningsberger, op cit at 169. Some works, such as Girl with a Flute, are disputed

[13] Grand Theatre of Dutch Painters and Women Artists

[14] Waiboer, op cit at at 3

[15] Husband of the artist Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun

[16] Cabanne, op cit at 243

[17] Cabanne, op cit at 243

[18] Villa, op cit at 8

[19] Cabanne, op cit at 247

[19A] Letter to Emile Bernard 29/7/1888

[20] Villa, op cit at 10

[21] Koningsberger, op cit at 125

[22] Koningsberger, op cit at 171

[23] Thomas Hoving, False Impressions: The Hunt for Big-time Art Fakes, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1996 at 175

[24] One notable exception was John Huizinga, who said that the work was “lacking in soul and only playing with colours”

[25] Equivalent to about $5 million today

[26] Hoving, op cit at 176

[27] Hoving, op cit at 178

[28] David Hockney, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, 2001; David Steadman: Vermeer’s Camera: Uncovering the Truth behind the Masterpieces, 2001; Tim Jenison, Tim’s Vermeer (documentary film) 2013

© Philip McCouat 2020, 2021, 2022

RETURN TO HOME