COLONIAL ARTIST, THIEF, FORGER AND MUTINEER:

thomas barrett's amazing career

|

By Philip McCouat

Thomas Barrett packed a lot of crime into his life-- multiple theft, forgery and even mutiny – and was sentenced to death three times. But the reason that we know about him today is because of an extraordinary four week period in his life – the period between the unexpected creation of his first artwork, a prized engraving recently sold for $750,000, and his untimely death at the age of only 30. Within that tiny timespan, surely the shortest artistic career on record, Barrett became not only the first colonial artist in Australia, but also the first person to be hanged in the infant colony. |

For reader comments on this article, see here

---------------------------------------- For more on crime... For more articles on art and crime, see: -------------------------------------------------- |

First death sentence: 1782

Thomas Barrett first definitely appears in the public records on 11 September 1782, when he was tried for theft at the Old Bailey in London [1]. It was not a sophisticated crime. According to the court records, he was indicted for taking a silver watch and other small items from the home of Ann Milton. The theft was discovered immediately, and two men, including Barrett, were seen running away. After cries of ‘Stop thief!’, he was caught and detained, with the watch being found in his possession. His defence - that the other escapee was a total stranger who just handed the watch to him -- was understandably rejected. He was found guilty and sentenced to death [2]. As was common in such cases, however, his death sentence was commuted to transportation for life to the colonies.

What did transportation actually mean? For most of the eighteenth century, right up until the American War of Independence (1775-1783), transportation had been Britain’s foremost criminal punishment. It was seen as an effective way of “draining the nation of its offensive rubbish, without taking away their lives” [3]. On average, about a thousand convicts, predominantly males, were transported each year to the American colonies, mostly to Maryland and Virginia. Most of these came from England, with a sizable minority from Ireland and smaller numbers from Scotland [4]. Given the conditions on board, and the generally poor condition of many of the convicts, the death rate during the voyage tended to be high, typically about 14% [5]. On arrival in the colony, the convicts could expect to be marched to the auction block, still in chains, and auctioned off, usually as field workers on plantations. Their status hovered somewhere above slaves and below white servants [6].

However, all immigration to North America ceased on the outbreak of the war, throwing the British criminal system into turmoil [7]. The ever-growing numbers of convicted criminals had to be housed somewhere, resulting in convicts being confined in crowded and unsanitary prison hulks, initially moored in the Thames Estuary. The position worsened when it became clear after the war that the Americans no longer wished (or needed) to accept any more convicts. In fact, it seems that there emerged a tendency in America to airbrush the whole convict experience out of its past. So, for example, Thomas Jefferson would claim in 1786 that:

What did transportation actually mean? For most of the eighteenth century, right up until the American War of Independence (1775-1783), transportation had been Britain’s foremost criminal punishment. It was seen as an effective way of “draining the nation of its offensive rubbish, without taking away their lives” [3]. On average, about a thousand convicts, predominantly males, were transported each year to the American colonies, mostly to Maryland and Virginia. Most of these came from England, with a sizable minority from Ireland and smaller numbers from Scotland [4]. Given the conditions on board, and the generally poor condition of many of the convicts, the death rate during the voyage tended to be high, typically about 14% [5]. On arrival in the colony, the convicts could expect to be marched to the auction block, still in chains, and auctioned off, usually as field workers on plantations. Their status hovered somewhere above slaves and below white servants [6].

However, all immigration to North America ceased on the outbreak of the war, throwing the British criminal system into turmoil [7]. The ever-growing numbers of convicted criminals had to be housed somewhere, resulting in convicts being confined in crowded and unsanitary prison hulks, initially moored in the Thames Estuary. The position worsened when it became clear after the war that the Americans no longer wished (or needed) to accept any more convicts. In fact, it seems that there emerged a tendency in America to airbrush the whole convict experience out of its past. So, for example, Thomas Jefferson would claim in 1786 that:

“[T]he Malefactors sent to America were not sufficient in number to merit enumeration as one class out of three which peopled America. It was at a late period of their history that the practice began. I have no book by me which enables me to point out the date of its commencement. But I do not think the whole number sent would amount to 2000 & being principally men eaten up with disease, they married seldom & propagated little. I do not suppose that themselves & their descendants are at present 4000, which is little more than one thousandth part of the whole inhabitants” [8].

This radically understated the real figures. In total, it appears that the American colonies received some 50,000+ convicts from Great Britain over the period 1718- 1775, contributing to an immigration mix during 1700-1775 of about 47% slaves, 9% convicts, 18% indentured servants, and 26% “free” persons [9].

Despite the emphatic American opposition to receiving convicts, the British tried to resume the transportation system after the war [10], sometimes even sending convicts disguised as indentured servants to the former colonies. However, the American authorities soon caught on to the practice and started turning boats back.

Despite the emphatic American opposition to receiving convicts, the British tried to resume the transportation system after the war [10], sometimes even sending convicts disguised as indentured servants to the former colonies. However, the American authorities soon caught on to the practice and started turning boats back.

Mutiny: 1784

Against this uncertain background, Barrett found himself allocated to a transportation ship, the Mercury, bound -- rather optimistically -- for Georgia. The Mercury set sail from Dover in March 1784, but the voyage proved to be unexpectedly short. Just a few days out, the convicts rose up violently against the crew and mutinied. According to some reports, Barrett himself appeared to have been involved, possibly even as one of the ringleaders. Once they were in control, the mutineers’ apparent intention to head for Ireland was thwarted by bad weather and they were forced to return to England. Many of the mutineers, including Barrett, were quickly recaptured. Barrett was again sentenced to death, and again reprieved. This time, apparently, it was because he had intervened during the mutiny to save the life of the Mercury’s steward [11] and had prevented another mutineer from cutting off the captain’s ear with scissors [12].

Transportation into the unknown: 1787

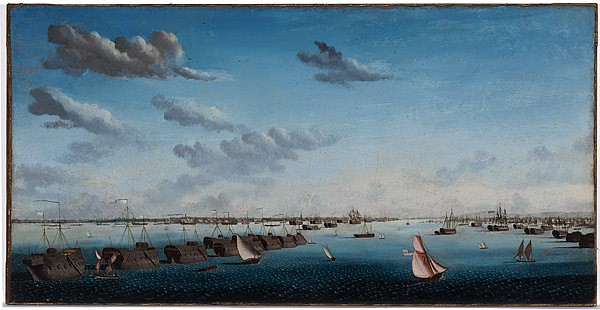

After this debacle, Barrett was sent to the prison hulk Dunkirk, moored at Plymouth, to await his next destination (Fig 1). By now, with the American option effectively having been closed off, Britain was proceeding with a new plan, this time to transport convicts to an even more remote destination – to Botany Bay, in the vast continent then known as New Holland, later to be called Australia [13]. At that time, although Captain Cook had mapped the east coast some years before, there was no European settlement there at all; the only occupants were its traditional owners the Eora Aborigines [14]. Accordingly, the British would be sending the convicts to help set up a brand new penal colony in a remote and undeveloped country, about which they knew little, and to do it from scratch. This was clearly an extremely risky and optimistic venture.

Fig 1: Ambroise-Louis Garneray, Portsmouth Harbour with Prison Hulks, c1814. National Gallery of Australia.

Barrett, by now aged about 29 [15], was among the batch of about 700 convicts that were “selected” to be included in the first wave of this bold new venture [16]. The “First Fleet”, as it was called, consisted of no fewer than 11 ships – two navy vessels, three store ships and six convict transports – under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, who was to be the governor of the new Colony, on board the flagship HMS Sirius. With over 1,400 people involved, this was “the biggest single overseas migration that the world had ever seen” [17].

Barrett, by now aged about 29 [15], was among the batch of about 700 convicts that were “selected” to be included in the first wave of this bold new venture [16]. The “First Fleet”, as it was called, consisted of no fewer than 11 ships – two navy vessels, three store ships and six convict transports – under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, who was to be the governor of the new Colony, on board the flagship HMS Sirius. With over 1,400 people involved, this was “the biggest single overseas migration that the world had ever seen” [17].

Fig 2: Frank Allen, The Charlotte at Portsmouth, May 1787 (1987). Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW.

Barrett’s ship, the Charlotte, was one of the convict transports (Fig 2). Like all the ships in the fleet, it was tiny by today’s standards, only 32 metres long [18]. In addition to the crew, naval officers and 42 marines and their families, it carried about 90 male convicts and 20-30 females, all drawn from the Dunkirk hulk, crowded and confined below decks. The convicts’ ages ranged from 17-61 with most in their 20s. Among them were two female convicts and 19 male convicts who had been involved in the Mercury mutiny [19].

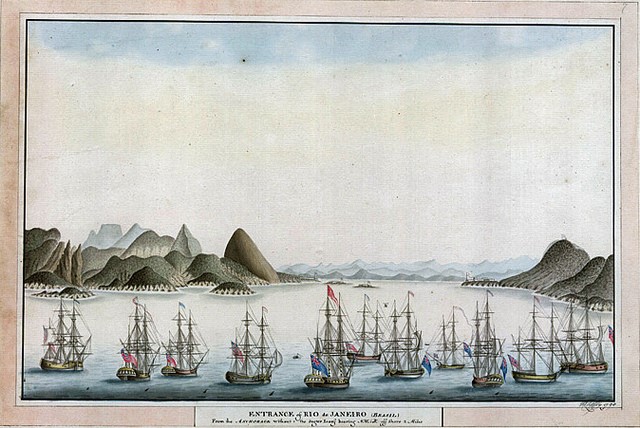

The fleet left from Spithead on 13 May 1787, bound for Botany Bay via the Canary Islands (off the west coast of Africa), Rio de Janiero and the Cape of Good Hope. As David Collins, an officer of marines on board the Sirius, would later remark, “all communication with family and friends with family and friends now cut off, we are leaving the world behind us, to enter a state unknown” [20].

Barrett’s ship, the Charlotte, was one of the convict transports (Fig 2). Like all the ships in the fleet, it was tiny by today’s standards, only 32 metres long [18]. In addition to the crew, naval officers and 42 marines and their families, it carried about 90 male convicts and 20-30 females, all drawn from the Dunkirk hulk, crowded and confined below decks. The convicts’ ages ranged from 17-61 with most in their 20s. Among them were two female convicts and 19 male convicts who had been involved in the Mercury mutiny [19].

The fleet left from Spithead on 13 May 1787, bound for Botany Bay via the Canary Islands (off the west coast of Africa), Rio de Janiero and the Cape of Good Hope. As David Collins, an officer of marines on board the Sirius, would later remark, “all communication with family and friends with family and friends now cut off, we are leaving the world behind us, to enter a state unknown” [20].

Forgery with buttons and buckles: 1787

|

Characteristically, it did not take long for Barrett to get into trouble again. This apparently started quite innocently. It seems that Barrett may have spent some time during the long Atlantic leg of the voyage in creating “love tokens”. These were metal discs usually made out of copper alloy, or low denomination copper coins that were sanded down, then inscribed with poems and statements of affection, and sold to fellow convicts as mementoes [21].

|

However, it soon became clear that Barrett was not just dealing in love tokens. The fleet’s Surgeon-General John White (Fig 3), who was also sailing on the Charlotte, tells what happened on the morning of 5 August 1787, as the ship was anchored off Rio [22]:

“[A] boat came alongside, in which were three Portugueze and six slaves, from whom we purchased some oranges, plantains, and bread. In trafficking with these people, we discovered that one Thomas Barret, a convict, had, with great ingenuity and address, passed some quarter dollars which he, assisted by two others, had coined out of old buckles, buttons belonging to the marines, and pewter spoons, during their passage from Teneriffe” .

It appeared that Barrett’s forging talents were quite exceptional. White noted that:

“the impression, milling, character, in a word, the whole was so inimitably executed that had their metal been a little better the fraud, I am convinced, would have passed undetected. A strict and careful search was made for the apparatus wherewith this was done, but in vain; not the smallest trace or vestige of any thing of the kind was to be found among them. How they managed this business without discovery, or how they could effect it at all, is a matter of inexpressible surprise to me, as they never were suffered to come near a fire and a centinel was constantly placed over their hatchway, which, one would imagine, rendered it impossible for either fire or fused metal to be conveyed into their apartments. Besides, hardly ten minutes ever elapsed, without an officer of some degree or other going down among them”.

White could not help but be impressed by Barrett’s enterprise, misdirected as it was. He commented:

“the adroitness … with which they must have managed, in order to complete a business that required so complicated a process, gave me a high opinion of their ingenuity, cunning, caution, and address; and I could not help wishing that these qualities had been employed to more laudable purposes.”

It is not clear what punishment, if any, Barrett received [23]. The principal concern of the British was instead more focused on mending relations with the locals. White records that:

“the officers of marines, the master of the ship, and myself fully explained to the injured Portugueze what villains they were who had imposed upon them. We were not without apprehensions that they might entertain an unfavourable opinion of Englishmen in general from the conduct of these rascals; we therefore thought it necessary to acquaint them that the perpetrators of the fraud were felons doomed to transportation, by the laws of their country, for having committed similar offences there.”

Botany Bay and the Charlotte Medal: January 1788

The Charlotte eventually reached Botany Bay on 20 February 1788, after a marathon voyage of about eight months from the other side of the world. Even then, however, the convicts were kept on board ship, and not able to go ashore, as it had quickly become evident that the Bay was quite unsuitable for the settlement. Fortunately, an alternative harbour landing was found just to the north, at Port Jackson – now known as Sydney Harbour (Fig 4). It was here that the Fleet eventually anchored, crews and passengers were disembarked and the flag was raised at Sydney Cove.

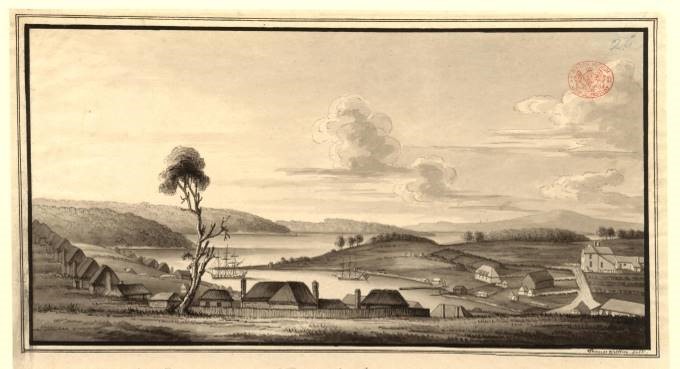

Fig 4: John Hunter, Sydney Cove 1788

During the tedious six day hiatus between arrival at Botany Bay and disembarking at Sydney Cove, Barrett had actually been respectably employed on a task which – ironically enough – utilised his recently-acquired forging skills. It seems that Surgeon White who, as we have seen, was greatly impressed with Barrett’s metalworking skills, commissioned him to make a memento of the arrival in the form of large engraved round silver medal [24].This would later become known as the Charlotte Medal (Fig 5), and has been described as one of the rarest, but one of the least--known, items of Australiana [25]. It remains one of the very few tangible relics of the First Fleet and, as far as we know, is the first European artwork made in the Colony [26].

Fig 5: Charlotte Medal (obverse), 1788 Australian National Maritime Museum

The medal is 74 mm across (almost 3 inches). On its front face (the “obverse”), there is an engraving of a fully-rigged ship at anchor. The sun is near the horizon, and the moon and some stars are depicted above the ship. Near the sun are the words “The Charlotte at anchor in Botany Bay, Jany 20, 1788”. Hosty describes the depiction of the ship as a fair representation of its type, but notes that some details understandably “suggest a landsman’s and not a sailor’s eye”, such as the gravity-defying anchor line and the deliberately naïve depictions of the moon, sun and stars [27].

Fig 6: Charlotte Medal (reverse), 1788 Australian National Maritime Museum

On back face of the medal (the “reverse”), in running script, are the navigational details of the voyage:

Sailed, the Charlotte from Spit Head the 13 of May 1787. Bound for Botany Bay in th Island of New Holland. Arriv’d at Teneriff th 4 of June in Lat 28.13 N long 16.23 W. Depart’d it 10 D. Arriv’d Rio Janiero 6 of Aug in Lat 22.54 S Long 42.38 W. Depart’d it th 5 of Sepr, arriv’d at the Cape of Good Hope the 14 Octr in Lat 34.29 S Long 18.29 E, Depart’d it th 13 of Novr and made the South Cape of New Holland the 8 Jan’y 1788 in Lat 43.32 S Long 146.56 E. Arriv’d at Botany Bay the 20 of Jany. The Charlotte in Co in Lat 34.00 South Long 151.00 East. Distance from Great Britan miles 13106

The medal is not signed (perhaps understandably), but is almost certainly attributable to Barrett. He was the only known forger on Charlotte and seems the only one on board who had the skills to produce such a fine work of art using primitive and minimal resources. Moreover, White was well-acquainted with Barrett’s skills, and would have been able to provide him with the navigational details appearing on the Medal, and also with the necessary silver – it is apparently from a piece of a surgeon’s kidney bowl.

White eventually returned to England in 1794, presumably with the Medal, but its whereabouts after that are not known until 1919, when it turned up in the collection of Princess Victoria (daughter of Queen Victoria) and her husband Prince Louis of Battenberg, later Admiral Louis Alexander Mountbatten, Marquis of Milford Haven and First Sea Lord of the Admiralty [28]. It was eventually acquired at auction by the National Maritime Museum of Australia in 2008 for AUD $750,000.

The publicity surrounding the purchase prompted the appearance of another medal, a smaller, punctured and battered copper disc with an abridged inscription and depictions of the sun, moon and stars, but no ship {Fig 7). It seems that this was a distinctly lesser version of the Charlotte Medal, done for White’s servant William Broughton (hence the initials “WB” deeply incised at its base), who eventually settled in the Camden area of NSW, where the medal was rediscovered during a house renovation in the 1940s [29].

White eventually returned to England in 1794, presumably with the Medal, but its whereabouts after that are not known until 1919, when it turned up in the collection of Princess Victoria (daughter of Queen Victoria) and her husband Prince Louis of Battenberg, later Admiral Louis Alexander Mountbatten, Marquis of Milford Haven and First Sea Lord of the Admiralty [28]. It was eventually acquired at auction by the National Maritime Museum of Australia in 2008 for AUD $750,000.

The publicity surrounding the purchase prompted the appearance of another medal, a smaller, punctured and battered copper disc with an abridged inscription and depictions of the sun, moon and stars, but no ship {Fig 7). It seems that this was a distinctly lesser version of the Charlotte Medal, done for White’s servant William Broughton (hence the initials “WB” deeply incised at its base), who eventually settled in the Camden area of NSW, where the medal was rediscovered during a house renovation in the 1940s [29].

Theft and execution: February 1788

Meanwhile, conditions in the new Colony were proving to be extremely testing, even dangerous. The Fleet had arrived during the heat of summer after a long voyage. Food and other supplies were scarce and had to be strictly rationed from the start. The threat and/or fear of starvation, illness, rebellion or attack, in an unknown and unfamiliar environment, created a volatile situation that called on all of Governor Phillip’s abilities to keep under control. On 7 February, he gave a stern lecture to the assembled convicts, warning them, among other things, that in view of the shortness of rations, stealing would be punished by death, and that he would not be lenient [30].

Barrett, however, evidently took little notice of the warning, with the result that his fledging new career as a respectable artist turned out to be remarkably short. Late in February, he and a number of others were implicated in an organised theft of government rations (beef, butter and “pease”) [31]. Barrett was charged, with three others, with feloniously and fraudulently taking away public stores. All four were found guilty, with three including Barrett being sentenced to death, and the fourth receiving a severe flogging.

The wheels of justice moved fast in the Colony, and the sentence was carried out just after 6pm on the very same day [32]. Due to a rumour that the assembled convicts might rise up to stop the hanging, or to attempt a rescue, a large number of marines were present, all armed. White’s Journal describes the scene:

Barrett, however, evidently took little notice of the warning, with the result that his fledging new career as a respectable artist turned out to be remarkably short. Late in February, he and a number of others were implicated in an organised theft of government rations (beef, butter and “pease”) [31]. Barrett was charged, with three others, with feloniously and fraudulently taking away public stores. All four were found guilty, with three including Barrett being sentenced to death, and the fourth receiving a severe flogging.

The wheels of justice moved fast in the Colony, and the sentence was carried out just after 6pm on the very same day [32]. Due to a rumour that the assembled convicts might rise up to stop the hanging, or to attempt a rescue, a large number of marines were present, all armed. White’s Journal describes the scene:

“[the prisoners]… were taken to the fatal tree, where Barrett was launched into eternity, after having confessed to the Rev Mr Johnson, who attended him, that he was guilty of the crime, and had long merited the ignominious death which he was about to suffer, and to which he said he had been brought by bad company and evil example. [The two others] were respited until six o’clock the next evening. When that awful hour arrived, they were led to the place of execution, and, just as they were on the point of ascending the ladder, the judge advocate arrived with the governor’s pardon, on condition of their being banished to some uninhabited place.”[33]

Another eye witness, Watkin Tench, described Barrett as an “unhappy wretch… an old and desperate offender, who died with that hardy spirit which too often is found in the worst and most abandoned class of men” [34]. Another onlooker noted that Barrett showed no remorse until close to the very end: “He was the most undaunted of any man I ever saw in a similar horrid predicament and never appeared the least concerned or distressed till he mounted the ladder, when he turned very pale. He spoke to one of the convict men… before he was ‘turned off’” [35].

Fig 8: Thomas Watling, An east view of Port-Jackson, and Sydney-Cove, taken from behind the New Barracks c 1792: First Fleet Collection, Natural History Museum, London. .

Barrett thus became the first person executed in the Colony, and the first European to be executed on the east coast [36]. It would be the first of hundreds of hangings in the Colony [37], yet there still was not even a public hangman. As it happened, this problem was solved very shortly, though in an unorthodox way. Two days after Barrett’s execution, another offender, James Freeman was “convicted and sentenced to be hanged; but while under the ladder, with the rope about his neck, he was offered his free pardon on condition of performing the duty of the common executioner as long as he remained in this country; which, after some little pause, he reluctantly accepted” [38].

The place of execution came to be known as Hangman’s Hill (Fig 8). Barrett would have been hanged on the rise at left, near the depicted line of barrack buildings. (Some 200 years later the Sydney Opera House would be built on the point behind, and to the right of, the tall tree shown). You can, if you are so minded, go there today, though the busy urban streetscape naturally bears no resemblance to how it was in 1788.

The place of execution came to be known as Hangman’s Hill (Fig 8). Barrett would have been hanged on the rise at left, near the depicted line of barrack buildings. (Some 200 years later the Sydney Opera House would be built on the point behind, and to the right of, the tall tree shown). You can, if you are so minded, go there today, though the busy urban streetscape naturally bears no resemblance to how it was in 1788.

Fig 9: Thomas Barrett Memorial Plaque, the Rocks, Sydney

Here, tucked away at the corner of Harrington and Essex Streets in the Rocks area of Sydney, just outside the tourist precinct, you will come across a round plaque placed by the Royal Australian Historical Society (Fig 9). It simply reads:“Thomas Barrett, a First Fleet convict, was hanged near this place on 27 February 1788 for stealing provisions and was buried nearby.” Perhaps he lies there still.

© Philip McCouat 2015

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Thomas Barrett: colonial artist, thief, forger and mutineer”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

If you enjoyed this article, you may also be interested in:

We welcome your comments

Back to Home

© Philip McCouat 2015

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Thomas Barrett: colonial artist, thief, forger and mutineer”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

If you enjoyed this article, you may also be interested in:

- the extraordinary life of another transportee, John Tawell, the Quaker murderer: see here

- how destroyed Patagonian Indian cultures have lived on through their art: see here

We welcome your comments

Back to Home

End notes

1. A man called “Thomas Barret” had also been charged with a different case of theft, just three months before, but was found not guilty on the grounds of insufficient evidence. It is very possible that this was the same man:

http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17820703-6&div=t17820703-6&terms=thomas%20barrett%201782#highlight

2. Case 511: http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17820911-28&div=t17820911-28&terms=thomas%20barret%201782#highlight

3. A Roger Ekirch, “Bound for America: A Profile of British Convicts Transported to the Colonies, 1718-1775”, The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 2 (Apr 1985), pp. 184-200, at 184.

4. Ekirch, op cit at 186.

5. Aaron S. Fogleman, “From Slaves, Convicts, and Servants to Free Passengers: The Transformation of Immigration in the Era of the American Revolution”, The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 1 (Jun., 1998), pp. 43-76, at 56.

6. Fogleman, op cit at 57.

7. Fogleman, op cit at 61.

8. Thomas Jefferson, The Works of Thomas Jefferson: Correspondence (Vol 5) 1786-1787, Cosimo Inc 2010 (google e-book).

9. Fogleman, op cit at 44.

10. Kieran Hosty, “The Charlotte Medal”, Signals 84, September – November 2008 (Australian National Maritime Museum), 10-15.

11. Hosty, op cit at 12.

12. The Mercury later sailed again for America, but was refused permission to land there. It then went to the Honduras, but its eventual fate is unknown.

13. Fogleman, op cit at 61; Ekirch, op cit. The name “Australia” was not officially used until 1824.

14. Unfortunately, little thought was given to their legitimate property rights. For an interesting account of contacts between the Eora and the British, see Susan Boyer, Across Great Divides: True Stories of Life at Sydney Cove, Birrong Books, Glenbrook, 2013.

15. Some accounts suggest that Barrett was only 17 or 18, eg Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore; A History of the Transportation of Convicts to Australia, 1787-1868, Collins Harvill, London, 1987, at 91; Thomas Keneally, The Commonwealth of Thieves: The Sydney Experiment, Random House, Sydney, 2005, at 160. This does not appear to be correct.

16. About 160,000 convicts would eventually be transported to Australia over the next 80 years.

17. David Hill, 1788: The Brutal Truth of the First Fleet, Wm Heinemann, Sydney 2008, at 1.

18. Equivalent to about 110 feet. For detailed dimensions, see www.dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/charlotte

19. Three of those also participated in an earlier mutiny on the Swift in 1783 www.dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/charlotte

20. David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, 1798, Vol 1, Section 2. Collins would perform a number of crucial roles in the Colony, including Deputy Judge Advocate and Lieutenant-Governor.

21. Hosty, op cit at 12.

22. John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, 1790. Original spelling is retained here and in other quotations, except where necessary for clarity. White later became the first Surgeon-General of New South Wales. His Journal is an invaluable first-hand account of the voyage and the early settlement. It is also considered to be the earliest book of Australian natural history.

23. Hughes, op cit, at 81, says that Barrett was “lightly punished”, but that a marine who had tried to pass off one of the coins on shore got 200 lashes. It seems that marines were apparently punished for such trangressions more severely than convicts.

24. Hosty, op cit: John Chapman, “The solution of the Charlotte enigma”, Journal of the Numismatics Association of Australia, (1998), vol 9, 28-33.

25. Hosty, op cit at 11.

26. Of course, Aboriginal art had already been flourishing for tens of thousands of years.

27. Hosty, op cit.

28. Hosty, op cit at 15.

29. Chapman, op cit.

30. Boyer, op cit at 40.

31. Pease was a porridge of compacted peas.

32. Arthur Bowes Smyth, The Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth, Surgeon, Lady Penrhyn, 1787-1789, quoted in David Hill, First Fleet Surgeon: The Voyage of Arthur Bowes Smyth, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2015.

33. White, op cit.

34. Watkin Tench, A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay, ch 10. Tench was an officer of marines on the Charlotte.

35. Bowes Smyth, op cit.

36. The Dutch had executed some of Batavia mutineers on the Abrolhos Islands off Western Australia in 1629.

37. Capital punishment was in practice abandoned in NSW in 1939.

38. White, op cit.

© Philip McCouat 2015

Back to Home

http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17820703-6&div=t17820703-6&terms=thomas%20barrett%201782#highlight

2. Case 511: http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17820911-28&div=t17820911-28&terms=thomas%20barret%201782#highlight

3. A Roger Ekirch, “Bound for America: A Profile of British Convicts Transported to the Colonies, 1718-1775”, The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 2 (Apr 1985), pp. 184-200, at 184.

4. Ekirch, op cit at 186.

5. Aaron S. Fogleman, “From Slaves, Convicts, and Servants to Free Passengers: The Transformation of Immigration in the Era of the American Revolution”, The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 1 (Jun., 1998), pp. 43-76, at 56.

6. Fogleman, op cit at 57.

7. Fogleman, op cit at 61.

8. Thomas Jefferson, The Works of Thomas Jefferson: Correspondence (Vol 5) 1786-1787, Cosimo Inc 2010 (google e-book).

9. Fogleman, op cit at 44.

10. Kieran Hosty, “The Charlotte Medal”, Signals 84, September – November 2008 (Australian National Maritime Museum), 10-15.

11. Hosty, op cit at 12.

12. The Mercury later sailed again for America, but was refused permission to land there. It then went to the Honduras, but its eventual fate is unknown.

13. Fogleman, op cit at 61; Ekirch, op cit. The name “Australia” was not officially used until 1824.

14. Unfortunately, little thought was given to their legitimate property rights. For an interesting account of contacts between the Eora and the British, see Susan Boyer, Across Great Divides: True Stories of Life at Sydney Cove, Birrong Books, Glenbrook, 2013.

15. Some accounts suggest that Barrett was only 17 or 18, eg Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore; A History of the Transportation of Convicts to Australia, 1787-1868, Collins Harvill, London, 1987, at 91; Thomas Keneally, The Commonwealth of Thieves: The Sydney Experiment, Random House, Sydney, 2005, at 160. This does not appear to be correct.

16. About 160,000 convicts would eventually be transported to Australia over the next 80 years.

17. David Hill, 1788: The Brutal Truth of the First Fleet, Wm Heinemann, Sydney 2008, at 1.

18. Equivalent to about 110 feet. For detailed dimensions, see www.dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/charlotte

19. Three of those also participated in an earlier mutiny on the Swift in 1783 www.dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/charlotte

20. David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, 1798, Vol 1, Section 2. Collins would perform a number of crucial roles in the Colony, including Deputy Judge Advocate and Lieutenant-Governor.

21. Hosty, op cit at 12.

22. John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, 1790. Original spelling is retained here and in other quotations, except where necessary for clarity. White later became the first Surgeon-General of New South Wales. His Journal is an invaluable first-hand account of the voyage and the early settlement. It is also considered to be the earliest book of Australian natural history.

23. Hughes, op cit, at 81, says that Barrett was “lightly punished”, but that a marine who had tried to pass off one of the coins on shore got 200 lashes. It seems that marines were apparently punished for such trangressions more severely than convicts.

24. Hosty, op cit: John Chapman, “The solution of the Charlotte enigma”, Journal of the Numismatics Association of Australia, (1998), vol 9, 28-33.

25. Hosty, op cit at 11.

26. Of course, Aboriginal art had already been flourishing for tens of thousands of years.

27. Hosty, op cit.

28. Hosty, op cit at 15.

29. Chapman, op cit.

30. Boyer, op cit at 40.

31. Pease was a porridge of compacted peas.

32. Arthur Bowes Smyth, The Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth, Surgeon, Lady Penrhyn, 1787-1789, quoted in David Hill, First Fleet Surgeon: The Voyage of Arthur Bowes Smyth, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2015.

33. White, op cit.

34. Watkin Tench, A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay, ch 10. Tench was an officer of marines on the Charlotte.

35. Bowes Smyth, op cit.

36. The Dutch had executed some of Batavia mutineers on the Abrolhos Islands off Western Australia in 1629.

37. Capital punishment was in practice abandoned in NSW in 1939.

38. White, op cit.

© Philip McCouat 2015

Back to Home