THE ISENHEIM ALTARPIECE

Pt 2: NATIONALISm, nazism AND DEGENERAcy

introduction: THE MONUMENTS MEN

|

Following the D-Day landings in May 1944, as the Allied forces advanced rapidly into Europe, a major effort was made to locate and safeguard the thousands of works of art that had been hidden away to protect them from war damage. There was also an urgent need to protect artworks from further accidental or wanton destruction (by either side). and to prevent the large-scale looting or seizure of works – supposedly “for safekeeping”— by the retreating German forces.

|

------------------------------------------------

For more on art and war, see: The shocking birth and amazing career of Guernica From the Rokeby Venus to Fascism Pt 2: the strange allure of fascism Bellotto and the reconstruction of Warsaw ------------------------------------------------ |

This challenging task was undertaken by a little-known multinational group known as the Monuments, Fine Art and Archives section (MFAA). These remarkable, under-resourced “Monuments Men” (as they became known), had volunteered to work with regular troops on or close to the front line, sometimes in conditions of considerable danger, but they were hardly your typical soldiers – many of them were middle-aged museum directors, artists, art scholars, curators and conservators [1]. Despite this (or because of it), their efforts would prove to be extraordinarily fruitful [1A].

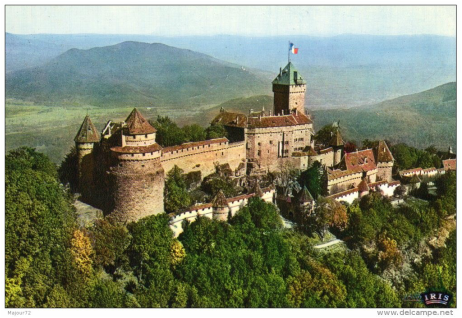

By late 1944, some 3,000 US infantry troops had pushed into Alsace, which had been reclaimed by Germany earlier in the war. Some of that region’s greatest treasures had been stored by the Germans in the imposing fifteenth-century Château du Haut-Koenigsbourg (Fig 1) [2]. When US troops took it over, they trashed a former bedroom of Kaiser Wilhelm II, stole some banners, and used tapestries as rugs and blackout curtains. This behaviour was, however, relatively restrained compared to some other cases. Lynn Nicholas records that “directives on the subject, issued at regular intervals, had little effect on the cold and exhausted troops. As one normally gentle soul explained, ‘If right after the battle you came into a beautiful room in a chateau, you had to shoot the chandeliers’”[3].

By late 1944, some 3,000 US infantry troops had pushed into Alsace, which had been reclaimed by Germany earlier in the war. Some of that region’s greatest treasures had been stored by the Germans in the imposing fifteenth-century Château du Haut-Koenigsbourg (Fig 1) [2]. When US troops took it over, they trashed a former bedroom of Kaiser Wilhelm II, stole some banners, and used tapestries as rugs and blackout curtains. This behaviour was, however, relatively restrained compared to some other cases. Lynn Nicholas records that “directives on the subject, issued at regular intervals, had little effect on the cold and exhausted troops. As one normally gentle soul explained, ‘If right after the battle you came into a beautiful room in a chateau, you had to shoot the chandeliers’”[3].

Fortunately, the troops left untouched a series of rooms filled with what Monuments officer Marvin Ross later described as an “astounding array” of medieval and Renaissance paintings and sculptures. Even these, however, paled in contrast to the discovery that was ultimately made in the cellar. In the centre of that room, heavily braced by large timbers, and guarded by curator M Pauli, who had evidently slept there at all times, stood the extraordinary multiple panels of Matthias Grünewald's famous Isenheim Altarpiece [4].

The recovery of the Altarpiece, and its subsequent relocation to its home at the Musée Unterlinden in nearby Colmar, marked the final stage of a period when the Altarpiece became a pawn in a desperate power struggle between nations and between ideologies. Here then is the story of that tumultuous period.

The recovery of the Altarpiece, and its subsequent relocation to its home at the Musée Unterlinden in nearby Colmar, marked the final stage of a period when the Altarpiece became a pawn in a desperate power struggle between nations and between ideologies. Here then is the story of that tumultuous period.

THE ALTARPIECE AND NATIONALISM

The history of the Altarpiece has always been bound up with political events and, in particular, with the long-continuing enmity between France and Germany [5]. The Altarpiece’s location in Alsace – positioned so close to the joint border and therefore constantly in dispute – meant that control of the work has alternated constantly between the two countries according to the fortunes of war.

Over the last 150 years, the territory of Alsace has experienced multiple changes of control, resulting from three major conflicts. The first of these, the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71, resulted in control of Alsace-Lorraine passing from France to Germany. It is probably not coincidental that it was about this time that some German writers developed the concept that the Altarpiece somehow represented the essential character of the German nation. This character was supposedly marked by “melancholy, a deep spiritual apprehension of the universe, inwardness and angst” [6]. Physical possession of the Altarpiece within German territory therefore began to be associated with the concept of Germany’s “natural” or “cultural” borders.

Later, during the chaos of the First World War, German military authorities had the Altarpiece transported from Alsace to the Pinakothek in Munich for safekeeping. After being restored and cleaned, the Altarpiece was put on exhibition there. In this far more accessible location, at a time of war-induced misery, and with the Altarpiece’s emphasis on death, suffering and resistance, it immediately became the object of German pilgrimage and an extraordinary level of veneration [7]. Stieglitz records that special tours to see the Altarpiece were arranged for those coming from out of town, “and wounded soldiers, many limbless, were wheeled in front of it, where religious services were held.” One writer reported:

“Never before could people have made such a pilgrimage to an altar; it was like in the Middle Ages. They came. They were drawn to it. The altar was a magnet. . . .A changed spirit moved even in the dumb worship of the most wretched. After the mechanisms of more than four years of war, the masses gathered together for the first time before the Spirit of a German artist – probably the greatest we have ever had – to share their innermost common predicament.“[8].

The extremity of this reaction gave even greater significance to the fact that Germany’s ultimate defeat in the war meant that the Altarpiece had to be returned to Alsace which, under the Treaty of Versailles, had once more reverted to France. The Altarpiece’s actual removal, in 1919, was marked by further outpourings of regret and loss. One Munich newspaper reported how a group of eager spectators, of all ages, gender and classes waited to see the final opening of the altar:

“The people stood and stared: moved, unsuspecting, knowing: the most touching were those with the reverent expressions of the shattered lay person. Schoolboys of ten or twelve with coloured caps, or bare heads; workers; citizens; ‘world’ painters; old people; children […]. The red removal van stood below. A wretched reality: like coffin and grave. The lost war. One cannot keep back this thought; and it is neither unobjective nor sentimental. A piece of Germany is being cut away, the most noble part: Alsace. Alemannia. Grünewald.”[9]..

For many Germans, the removal of the Altarpiece to France therefore was a tangible representation of a multiple loss – the territorial loss of Alsace, Germany’s loss of the war, its loss of dignity as a result of what it saw as the deeply of humiliating terms of the peace treaty, and the loss of a painting and painter who had become closely linked to perceived concepts of German-ness.

Over the last 150 years, the territory of Alsace has experienced multiple changes of control, resulting from three major conflicts. The first of these, the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71, resulted in control of Alsace-Lorraine passing from France to Germany. It is probably not coincidental that it was about this time that some German writers developed the concept that the Altarpiece somehow represented the essential character of the German nation. This character was supposedly marked by “melancholy, a deep spiritual apprehension of the universe, inwardness and angst” [6]. Physical possession of the Altarpiece within German territory therefore began to be associated with the concept of Germany’s “natural” or “cultural” borders.

Later, during the chaos of the First World War, German military authorities had the Altarpiece transported from Alsace to the Pinakothek in Munich for safekeeping. After being restored and cleaned, the Altarpiece was put on exhibition there. In this far more accessible location, at a time of war-induced misery, and with the Altarpiece’s emphasis on death, suffering and resistance, it immediately became the object of German pilgrimage and an extraordinary level of veneration [7]. Stieglitz records that special tours to see the Altarpiece were arranged for those coming from out of town, “and wounded soldiers, many limbless, were wheeled in front of it, where religious services were held.” One writer reported:

“Never before could people have made such a pilgrimage to an altar; it was like in the Middle Ages. They came. They were drawn to it. The altar was a magnet. . . .A changed spirit moved even in the dumb worship of the most wretched. After the mechanisms of more than four years of war, the masses gathered together for the first time before the Spirit of a German artist – probably the greatest we have ever had – to share their innermost common predicament.“[8].

The extremity of this reaction gave even greater significance to the fact that Germany’s ultimate defeat in the war meant that the Altarpiece had to be returned to Alsace which, under the Treaty of Versailles, had once more reverted to France. The Altarpiece’s actual removal, in 1919, was marked by further outpourings of regret and loss. One Munich newspaper reported how a group of eager spectators, of all ages, gender and classes waited to see the final opening of the altar:

“The people stood and stared: moved, unsuspecting, knowing: the most touching were those with the reverent expressions of the shattered lay person. Schoolboys of ten or twelve with coloured caps, or bare heads; workers; citizens; ‘world’ painters; old people; children […]. The red removal van stood below. A wretched reality: like coffin and grave. The lost war. One cannot keep back this thought; and it is neither unobjective nor sentimental. A piece of Germany is being cut away, the most noble part: Alsace. Alemannia. Grünewald.”[9]..

For many Germans, the removal of the Altarpiece to France therefore was a tangible representation of a multiple loss – the territorial loss of Alsace, Germany’s loss of the war, its loss of dignity as a result of what it saw as the deeply of humiliating terms of the peace treaty, and the loss of a painting and painter who had become closely linked to perceived concepts of German-ness.

EMOTION, BLASPHEMY AND OBSCENITY

The next stage in the saga of the Altarpiece emerged from an unexpected source – the emergence of the Expressionist art movement. This movement had originated round the start of the century. It was spurred by the establishment of the associations known as the Brücke (“Bridge”) and the Blaue Reiter (“Blue Rider”) and developed with input from artists such as Kokoshka, Kollwitz and Beckmann. In the immediate post-war period of the Weimar Republic in Germany, the movement became particularly fashionable.

Expressionism covered a multitude of styles, but in general it was characterised by a direct rendering of emotions and feelings. Line, form and colour were used for their expressive possibilities, instead of being primarily representational. Grünewald and his Altarpiece, with its strong association with violent sensation and emotion, therefore became a natural source of inspiration for many Expressionist artists [10].

While Expressionism had always had some level of involvement with social issues, this became acute in the mid-1920s with the development of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), which added a bitter, satirical, sometimes crude and almost caricaturist element. This proved to be far more confronting to the authorities. Although the Constitution guaranteed freedom of expression, the Criminal Code forbade the publication of obscene or indecent writings or illustrations. With some artists, the government appears to have embraced this power with some enthusiasm, confiscating a wide range of material that it deemed unacceptable.

Just such an artist was George Grosz. He felt that the period he was living in was a transitional one, similar to that of the Middle Ages, and saw his own art as being similar to the “moral criticism and Jeremiah-like art of Bruegel, Bosch and Grünewald” [11]. A copy of Grünewald’s Crucifixion actually hung on his studio wall [12]. Grosz, a veteran of World War I, considered that contemporary artists should adapt the old images and symbols (such as the Crucifixion) and invest them with references to the political and ideological struggles of the 20th century [13]. His deliberately-provocative works, designed to highlight what he saw as the decadence of German society, brought him into constant difficulties with the authorities, and he had early convictions for defaming the military, and obscenity.

Expressionism covered a multitude of styles, but in general it was characterised by a direct rendering of emotions and feelings. Line, form and colour were used for their expressive possibilities, instead of being primarily representational. Grünewald and his Altarpiece, with its strong association with violent sensation and emotion, therefore became a natural source of inspiration for many Expressionist artists [10].

While Expressionism had always had some level of involvement with social issues, this became acute in the mid-1920s with the development of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), which added a bitter, satirical, sometimes crude and almost caricaturist element. This proved to be far more confronting to the authorities. Although the Constitution guaranteed freedom of expression, the Criminal Code forbade the publication of obscene or indecent writings or illustrations. With some artists, the government appears to have embraced this power with some enthusiasm, confiscating a wide range of material that it deemed unacceptable.

Just such an artist was George Grosz. He felt that the period he was living in was a transitional one, similar to that of the Middle Ages, and saw his own art as being similar to the “moral criticism and Jeremiah-like art of Bruegel, Bosch and Grünewald” [11]. A copy of Grünewald’s Crucifixion actually hung on his studio wall [12]. Grosz, a veteran of World War I, considered that contemporary artists should adapt the old images and symbols (such as the Crucifixion) and invest them with references to the political and ideological struggles of the 20th century [13]. His deliberately-provocative works, designed to highlight what he saw as the decadence of German society, brought him into constant difficulties with the authorities, and he had early convictions for defaming the military, and obscenity.

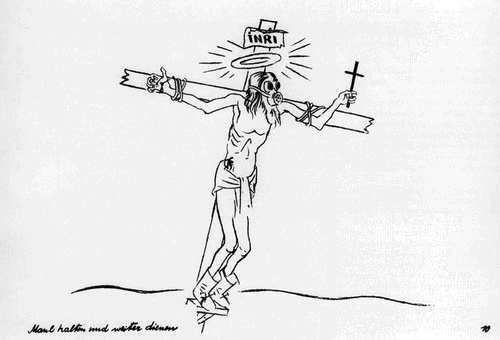

Grosz’s most controversial and best-known works, Hintergrund (“Backdrop”), a series of satirical drawings, led to charges under the prohibition of blasphemy. These would eventually result in the most protracted trial of its kind in German legal history [14]. The trial centered on one drawing in particular, a sketch depicting Christ being crucified in a gas mask and army boots, with the notation “Shut up and do your duty” (Fig 2) [15]. Although Grosz was ultimately acquitted, his success was soured by the confiscation of the offending material.

Grosz’s colleague, Otto Dix, also ran into considerable difficulties. Dix had also served in the trenches of the First World War, and was both repelled and fascinated by the experience. He would comment, “War is something horrible, but nonetheless something powerful… Under no circumstances could I miss it! It is necessary to see people in this unchained condition in order to know something about man”[16]. Dix’s artworks, with their elements of eroticism, disfigurement, war and radical social criticism were controversial, provoking an (unsuccessful) trial for pornography (for Girl before Mirror, 1922). Right-wing nationalists targeted Dix for what they saw as his defeatist, unpatriotic, anti-militaristic stance. Some claimed that Dix, a communist, was associated with a left-wing plot to undermine German morality and mores.

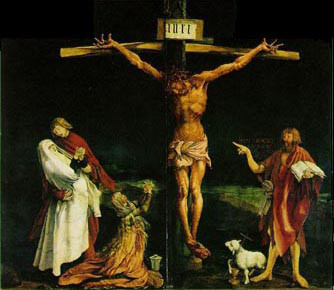

Dix had previously written that, “What we need for the future is a fanatical and impassioned naturalism, a fervent and unerring truthfulness”. Like Grosz, he explicitly harked back to the art of Grünewald, Bosch and Bruegel [17].. In paintings such as The Trench (1920-23) [18], which starkly depicted the rotting corpses of defeated German soldiers, there are echoes of the Temptation of St Anthony panel; from the Isenheim Altarpiece, “a representation of struggle and destruction in which the saint, like the soldier, is delivered over to the omnipotent forces of evil” [19]. Similarly, in his gruesome triptych The War (1929-32), he re-invents the Isenheim Altarpiece by substituting the horror of war for the horror of the crucifixion, using the same media (tempera on wood), a similar multi-panel format and the same vocabulary of suffering (Fig 3)

Grosz’s colleague, Otto Dix, also ran into considerable difficulties. Dix had also served in the trenches of the First World War, and was both repelled and fascinated by the experience. He would comment, “War is something horrible, but nonetheless something powerful… Under no circumstances could I miss it! It is necessary to see people in this unchained condition in order to know something about man”[16]. Dix’s artworks, with their elements of eroticism, disfigurement, war and radical social criticism were controversial, provoking an (unsuccessful) trial for pornography (for Girl before Mirror, 1922). Right-wing nationalists targeted Dix for what they saw as his defeatist, unpatriotic, anti-militaristic stance. Some claimed that Dix, a communist, was associated with a left-wing plot to undermine German morality and mores.

Dix had previously written that, “What we need for the future is a fanatical and impassioned naturalism, a fervent and unerring truthfulness”. Like Grosz, he explicitly harked back to the art of Grünewald, Bosch and Bruegel [17].. In paintings such as The Trench (1920-23) [18], which starkly depicted the rotting corpses of defeated German soldiers, there are echoes of the Temptation of St Anthony panel; from the Isenheim Altarpiece, “a representation of struggle and destruction in which the saint, like the soldier, is delivered over to the omnipotent forces of evil” [19]. Similarly, in his gruesome triptych The War (1929-32), he re-invents the Isenheim Altarpiece by substituting the horror of war for the horror of the crucifixion, using the same media (tempera on wood), a similar multi-panel format and the same vocabulary of suffering (Fig 3)

As Goerig-Hergott has observed, “Whereas, in Grünewald’s work, the finger of Saint John the Baptist is pointing toward Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross [fig 4] and the redemption it makes possible, the finger of the dead, impaled man hovering above the sinister, smashed-up landscape in Dix’s work points at the sacrifice of soldiers at war and, more precisely, at the corpse riddled with bullets, crucified upside down” [20].

THE NAZI CONCEPT OF DEGENERATE ART

If some modern artists like Dix had started feeling unloved during the Weimar years, they experienced far worse from 1933 onwards, when Hitler and the National Socialists came to power. Indeed, the Nazis appeared to take existing prejudices and attitudes to “incredible extremes”. Lynn Nicholas claims that “few could believe or wanted to acknowledge what was taking place before their very eyes” [21].

Paradoxically, part of the reason for this was that the Nazis placed an exaggeratedly high social value on the visual arts. Art was given a central role in public ceremony. It was granted an almost quasi-religious status as “a glorious expression of the most noble and heroic will” of the entire nation [22]. Hitler, a sadly rather amateurish painter in his earlier days, expressed an oddly intense form of love for art, or at least for the types of it that he understood. In 1936, he went so far as to say that, “Art is the only truly enduring investment of human labour” [23].

This elevated conception of art, and its supposedly-close connection with the national spirit, meant that it was in the national interest that art which did not conform to these lofty ideals must be eliminated. Very early in Hitler’s rule, the director of the Nazi-affiliated Combat League for German Culture stated the official position: “All the expressions of life spring from a specific blood, a specific race! Art is not international … There is no freedom for those who would weaken and destroy German art, there must be no remorse and no sentimentality in uprooting and crushing what was destroying our vitals”[24].

The works that were identified as particularly vitals-destroying were usually those which were “sketchy” or “unfinished”; works done by, or showing, Jews, Bolsheviks and "inferior" races; most modern art (often described as “pathological”); abstract works by artists such as Kandinsky (“insane”) and the German Expressionists (“syphilitic”, “infantile” and “insulting”); art with disordered or distorted colours or subject matter; art that expressed resistance to authority, or negative or defeatist sentiments, and so on. As we shall see, these would be officially classed under the general heading of “degenerate art”.

Later, Hitler was to make the official position on these unacceptable works even clearer, declaring that:“From now on we are going to wage a merciless war of destruction against the last remaining elements of cultural is integration….Should there be someone among [the artists] who still believes in his higher destiny – well now, he has had four years’ time to prove himself. The four years are sufficient for us, too, to reach a definite judgment. From now on – of that you can be certain – all those mutually supporting and thereby sustaining cliques of chatterers, dilettantes, and art forgers will be picked up and liquidated. For all we care, those prehistoric Stone-Age culture-barbarians and art-stutterers can return to the caves of their ancestors and there can apply their primitive international scratchings.”[25]

Extreme measures were taken against artists and others associated with the art scene who were regarded as not measuring up to the new ideals. Many museum directors and curators were dismissed from their government posts. Undesirable artists (such as Paul Klee) and dealers were dismissed from teaching posts or arts bodies and publicly ridiculed, vilified and intimidated. The sale or exhibition of their works was prohibited, and works were impounded without recompense [25A]. Some artists were forbidden to buy art supplies, with others such as Emile Nolde even being forbidden to paint [25B). Propaganda Minister Goebbels ultimately outlawed art criticism, declaring that “the art critic will be replaced by the art editor… In the future only those art editors will be allowed to report on art who approach the task with an undefiled heart and National Socialist convictions”[26].

Some artists had seen the writing on the wall early on, like George Grosz, who had already left Germany before Hitler became Chancellor in 1933 [27]. Many others emigrated or changed occupations once they realised the level of discrimination they would be facing. Still others, like Otto Dix, chose to undergo an “inner emigration” by modifying their styles. After being forced out of his job at the Dresden Academy, and being forbidden to exhibit his work, Dix had 260 of his works impounded by the government from collections throughout Germany. He retreated to Lake Constance. “I painted landscapes”, he said, “That was tantamount to emigration” [28].

In 1937, the government organised two major, definitive art exhibitions designed to justify and validate its cultural policy. The first exhibition marked the inauguration of the first major public building project of the Nazis – the impressive Haus der Kunst {“Home of German Art”). It was intended to show all that was good in art under the national socialist model, a genuine, German art that would break from the recent aberrations, draw on the established traditions and lay the foundations for art that would endure for a thousand years [29].

This exhibition featured works which, in essence, reflected Hitler’s personal artistic preferences and conceptions of essential German-ness. This tended to rule out most 20th century styles or innovations. Apart from Old Masters, the genres that found favour were those that fostered the “healthy folk feeling of Germany” such as landscapes, still lifes, and representations of blooming German peasant families; semi-mystical Nordic-like themes; portraits of acceptable persons; heroic military-themed scenes; steel-jawed and pectorally-endowed male nudes; pale pink and pliant female nudes; and works that were traditionally representational, realistic and “finished”.

The other exhibition, called Entartete Kunst (“Degenerate Art”) opened the following day. It was intended to demonstrate to the public all that was bad in the recent past – the unacceptable, and the un-German. The word “degenerate” was very carefully chosen. During this period in Germany, this word was not just used metaphorically – it carried specific overtones of a actual genetic deviation from the norm, and was aligned with other supposedly repellent “abnormalities” such as insanity or Jewishness (though, as it happened, most of the works were actually not by Jews).

The Degenerates exhibition was erratically hung, poorly lit, and complete with derisory captions for groups of works, such as “nature as seen by sick minds”. It featured over 600 works drawn from the 16,000-odd that had been confiscated over the previous four years [29A]. Predictably, works by Dix and Grosz were included, being collectively described as representing “art as a tool of Marxist propaganda against military service”. According to the Exhibition Guide, Dix fell into the category of “barbarism of representation… the progressive collapse of sensitivity to form and colour, the conscious disregard for the basics of technique… and the total stupidity of the choice of subject matter”. One commentator described Dix as standing at the peak of decadence, “with his vulgar derision of the war-wounded. He is representative of the highest contemptuousness” [30].

Paradoxically, part of the reason for this was that the Nazis placed an exaggeratedly high social value on the visual arts. Art was given a central role in public ceremony. It was granted an almost quasi-religious status as “a glorious expression of the most noble and heroic will” of the entire nation [22]. Hitler, a sadly rather amateurish painter in his earlier days, expressed an oddly intense form of love for art, or at least for the types of it that he understood. In 1936, he went so far as to say that, “Art is the only truly enduring investment of human labour” [23].

This elevated conception of art, and its supposedly-close connection with the national spirit, meant that it was in the national interest that art which did not conform to these lofty ideals must be eliminated. Very early in Hitler’s rule, the director of the Nazi-affiliated Combat League for German Culture stated the official position: “All the expressions of life spring from a specific blood, a specific race! Art is not international … There is no freedom for those who would weaken and destroy German art, there must be no remorse and no sentimentality in uprooting and crushing what was destroying our vitals”[24].

The works that were identified as particularly vitals-destroying were usually those which were “sketchy” or “unfinished”; works done by, or showing, Jews, Bolsheviks and "inferior" races; most modern art (often described as “pathological”); abstract works by artists such as Kandinsky (“insane”) and the German Expressionists (“syphilitic”, “infantile” and “insulting”); art with disordered or distorted colours or subject matter; art that expressed resistance to authority, or negative or defeatist sentiments, and so on. As we shall see, these would be officially classed under the general heading of “degenerate art”.

Later, Hitler was to make the official position on these unacceptable works even clearer, declaring that:“From now on we are going to wage a merciless war of destruction against the last remaining elements of cultural is integration….Should there be someone among [the artists] who still believes in his higher destiny – well now, he has had four years’ time to prove himself. The four years are sufficient for us, too, to reach a definite judgment. From now on – of that you can be certain – all those mutually supporting and thereby sustaining cliques of chatterers, dilettantes, and art forgers will be picked up and liquidated. For all we care, those prehistoric Stone-Age culture-barbarians and art-stutterers can return to the caves of their ancestors and there can apply their primitive international scratchings.”[25]

Extreme measures were taken against artists and others associated with the art scene who were regarded as not measuring up to the new ideals. Many museum directors and curators were dismissed from their government posts. Undesirable artists (such as Paul Klee) and dealers were dismissed from teaching posts or arts bodies and publicly ridiculed, vilified and intimidated. The sale or exhibition of their works was prohibited, and works were impounded without recompense [25A]. Some artists were forbidden to buy art supplies, with others such as Emile Nolde even being forbidden to paint [25B). Propaganda Minister Goebbels ultimately outlawed art criticism, declaring that “the art critic will be replaced by the art editor… In the future only those art editors will be allowed to report on art who approach the task with an undefiled heart and National Socialist convictions”[26].

Some artists had seen the writing on the wall early on, like George Grosz, who had already left Germany before Hitler became Chancellor in 1933 [27]. Many others emigrated or changed occupations once they realised the level of discrimination they would be facing. Still others, like Otto Dix, chose to undergo an “inner emigration” by modifying their styles. After being forced out of his job at the Dresden Academy, and being forbidden to exhibit his work, Dix had 260 of his works impounded by the government from collections throughout Germany. He retreated to Lake Constance. “I painted landscapes”, he said, “That was tantamount to emigration” [28].

In 1937, the government organised two major, definitive art exhibitions designed to justify and validate its cultural policy. The first exhibition marked the inauguration of the first major public building project of the Nazis – the impressive Haus der Kunst {“Home of German Art”). It was intended to show all that was good in art under the national socialist model, a genuine, German art that would break from the recent aberrations, draw on the established traditions and lay the foundations for art that would endure for a thousand years [29].

This exhibition featured works which, in essence, reflected Hitler’s personal artistic preferences and conceptions of essential German-ness. This tended to rule out most 20th century styles or innovations. Apart from Old Masters, the genres that found favour were those that fostered the “healthy folk feeling of Germany” such as landscapes, still lifes, and representations of blooming German peasant families; semi-mystical Nordic-like themes; portraits of acceptable persons; heroic military-themed scenes; steel-jawed and pectorally-endowed male nudes; pale pink and pliant female nudes; and works that were traditionally representational, realistic and “finished”.

The other exhibition, called Entartete Kunst (“Degenerate Art”) opened the following day. It was intended to demonstrate to the public all that was bad in the recent past – the unacceptable, and the un-German. The word “degenerate” was very carefully chosen. During this period in Germany, this word was not just used metaphorically – it carried specific overtones of a actual genetic deviation from the norm, and was aligned with other supposedly repellent “abnormalities” such as insanity or Jewishness (though, as it happened, most of the works were actually not by Jews).

The Degenerates exhibition was erratically hung, poorly lit, and complete with derisory captions for groups of works, such as “nature as seen by sick minds”. It featured over 600 works drawn from the 16,000-odd that had been confiscated over the previous four years [29A]. Predictably, works by Dix and Grosz were included, being collectively described as representing “art as a tool of Marxist propaganda against military service”. According to the Exhibition Guide, Dix fell into the category of “barbarism of representation… the progressive collapse of sensitivity to form and colour, the conscious disregard for the basics of technique… and the total stupidity of the choice of subject matter”. One commentator described Dix as standing at the peak of decadence, “with his vulgar derision of the war-wounded. He is representative of the highest contemptuousness” [30].

The Degenerates exhibition was a sensation, attracting hordes of presumably bewildered, predictably shocked members of the public. It toured Germany for four years, drawing a total of over three million non-paying visitors, making it perhaps the best-attended blockbuster (though definitely not best-loved) art exhibition in history.

Meanwhile, the Isenheim Altarpiece itself appeared to have fallen somewhat from its previous position of eminence in official eyes. This was largely due to its appropriation (or misappropriation) by the despised Expressionists and also – rather bizarrely – because of its close association with a 1934 opera by Paul Hindemith called Mathis der Maler (Matthias the painter). This opera, while outwardly fictional, was clearly inspired by Grünewald and his Altarpiece, and depicted an artist’s struggle for artistic freedom of expression in the repressive climate of his day. This aspect was hardly a theme that would appeal very much to the Nazi authorities, especially as Hindemith had some undesirable Jewish and bohemian associations, and as the opera was modernist and “difficult”. But Hindemith’s strong reputation, and the opera’s association with the revered Altarpiece – supposedly so emblematic of German-ness – and caused considerable angst in Nazi circles as to whether Hindemith (and, by association to some extent, the Altarpiece) should be considered “in” or “out”[31]. So far as the opera was concerned, the matter was finally settled late in 1934, when Propaganda Minister Goebbels denounced Hindemith as an “atonal noise-maker” [32] and performances of the opera were banned [33].

Meanwhile, the Isenheim Altarpiece itself appeared to have fallen somewhat from its previous position of eminence in official eyes. This was largely due to its appropriation (or misappropriation) by the despised Expressionists and also – rather bizarrely – because of its close association with a 1934 opera by Paul Hindemith called Mathis der Maler (Matthias the painter). This opera, while outwardly fictional, was clearly inspired by Grünewald and his Altarpiece, and depicted an artist’s struggle for artistic freedom of expression in the repressive climate of his day. This aspect was hardly a theme that would appeal very much to the Nazi authorities, especially as Hindemith had some undesirable Jewish and bohemian associations, and as the opera was modernist and “difficult”. But Hindemith’s strong reputation, and the opera’s association with the revered Altarpiece – supposedly so emblematic of German-ness – and caused considerable angst in Nazi circles as to whether Hindemith (and, by association to some extent, the Altarpiece) should be considered “in” or “out”[31]. So far as the opera was concerned, the matter was finally settled late in 1934, when Propaganda Minister Goebbels denounced Hindemith as an “atonal noise-maker” [32] and performances of the opera were banned [33].

CONCLUSION

This account of the Isenheim Altarpiece’s chequered role in Germany, from 1870 up to the end of World War II [34], underlines its remarkable capacity to be exploited in political ways – even to inspire political ideals that are radically opposed to one another. Whether Grünewald’s painting is perceived (or promoted) as an ultra-patriotic work defining the essence of German-ness; or as an overwrought proto-Expressionist outpouring with decadent associations; or as a haunting evocation of human suffering in times of oppression, it seems to reflect the fears, hopes and wishes of those who view it.

Now restored from its war-time sojourn to its traditional home in Colmar [35], the Altarpiece continues to be a striking example of the power of art. At the same time, it is a salutary reminder of how flexibly art can be used – or abused, according to your point of view – to influence wider social attitudes.□

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018.

How to cite this article

This article may be cited as:

Philip McCouat, “The Isenheim Altarpiece Pt 2: Nationalism, Nazism and Degeneracy”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

You may also enjoy….

If you enjoyed this article, you may also be interested in:

Now restored from its war-time sojourn to its traditional home in Colmar [35], the Altarpiece continues to be a striking example of the power of art. At the same time, it is a salutary reminder of how flexibly art can be used – or abused, according to your point of view – to influence wider social attitudes.□

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018.

How to cite this article

This article may be cited as:

Philip McCouat, “The Isenheim Altarpiece Pt 2: Nationalism, Nazism and Degeneracy”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

You may also enjoy….

If you enjoyed this article, you may also be interested in:

END NOTES

[1] Our account of the Monuments Men is based primarily on Lynn H Nicholas, The Rape of Europa, Papermac, London, 1994. A documentary film of the same name, based on this book, was also released in 2007. Other invaluable sources are Robert M Edsel, with Bret Witter, The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History, Hachette, New York, 2009; and Ilaria Dagnini Brey, The Venus Fixers: The Remarkable Story of the Allied Soldiers Who Saved Italy’s Art During World War II,. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2010; see also Nigel Pollard, "The real Monuments Men", BBC History Magazine, Feb 2014, 51-54. A film based loosely on the exploits of the Monuments Men, starring George Clooney, Matt Damon and Cate Blanchett, was released in 2014. For another film on the Nazis' artistic obsessions, see Hitler vs Picasso (2018). Both of these films are reviewed here

[1A] Among the many thousands of artworks recovered as a result of the Monuments Men's efforts were Leonardo da Vinci's Lady with an Ermine; Michelangelo's Madonna of Bruges; Manet's In the Conservatory; Vermeer's The Astronomer; and Rembrandt's 1645 Self-portrait.

[2] Now a popular tourist attraction in its own right.

[3] Nicholas, op cit at 303.

[4] Nicholas, op cit at 303-4, citing account of Monuments officer Marvin Ross, “Report of visit to Strasbourg 10-17 December, 1944”, US National Archives Washington, Record Group 239/28. Ross was an expert on Byzantine, Russian and 18th century French art: see entry at http://www.monumentsmenfoundation.org.

[5] Ann Stieglitz, “The Reproduction of Agony: Toward a Reception-History of Grünewald’s Isenheim Altar after the First World War”, Oxford Art Journal, Vol 12 No 2 (1989) 87.

[6] Stieglitz, op cit.

[7] Stieglitz, op cit; Keith Moxey, “Impossible Distance: Past and Present in the Study of Dürer and Grünewald”, The Art Bulletin, Vol 86 No 4 (Dec 2004), 750.

[8] Reinhhard Piper, cited in Stieglitz, op cit.

[9] Stieglitz, op cit.

[10] M Kay Flavell, George Grosz: A Biography, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1988, at 225.

[11] Beth Irwin Lewis, George Grosz: Art and Politics in the Weimar Republic. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1991, at 225.

[12] Flavell, op cit at 228.

[13] Flavell, op cit at 68.

[14] Michel White, “Not Another Blasphemy Trial; The Prosecution of George Grosz and Political Justice in Weimer Germany” in Daniel McClean (ed), The Trials of Art, Ridinghorse, London, 2007, at 225.

[15] The sketches were designed as accompaniments for a performance of The Good Solder Schweik.

[16] Reinhold Heller, entry on Otto Dix, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press 2009.

[17] Juliana D Kreinik, The Canvas and the Camera in Weimar Germany, (PhD diss), ProQuest, Ann Arbor, 2008.

[18] This painting has been missing since 1940.

[19] Frédérique Goerig-Hergott, “Otto Dix: Painting to Exorcise War”, at Arts & Societies Seminar Conjuring Away War, 3 March 2013.

[20] Goerig-Hergott, op cit.

[21] Nicholas, op cit at 6. For an account of the Nazi's similar approach to movie films, see Thomas Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler 1933-39, Columbia University Press, New York, 2013.

[22] Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1979, at 8.

[23] Hinz, op cit.

[24] Cited in Nicholas, op cit at 6.

[25] Speech by Hitler on the opening of the Home of German Art, 19 July 1937.

[25A] In November 2013 it was reported that a hoard of over 1,400 works had been discovered in the Munich apartment of Cornelius Gurlitt, the elderly son of a Nazi-era art dealer. Many of the works were by "degenerate" artists such as Dix, Beckmann, Kirchner, Picasso, Matisse, Toulouse-Lautrec, Chagall and Matisse. It is probable that the works were confiscated by the Nazis, or sold under duress as Jewish collectors were forced to unload art at worse than bargain prices: Philip Kennicott, "Works seized by Nazis as 'degenerate' electrify art world", Washington Post, 6 November 2013. For more details, see lootedart.com. For a complete list of confiscated degenerate art, see: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/e/entartete-kunst/

[25B] This was despite the fact that Nolde was himself a long-time Nazi.

[26] Nicholas, op cit at 16; Hinz, ch 1.

[27] Jonathan Petropoulos, Art as Politics in the Third Reich ,University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1996. See also generally Jonathan Petropoulos, The Faustian Bargain: The Art World in Nazi Germany, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000.

[28] Stephanie Barron, “1937: Modern Art and Politics in Prewar Germany”, in Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany, Harry A Abrams/Los Angeles County Museum of Art, New York, 1991, at 226.

[29] See generally Nicholas, op cit, Prologue.

[29A] There are currently unresolved questions over whether German museums have any legal or ethical rights to "degenerate" works that they were forced to deaccession by the Nazis: see Martin Bailey, "What next for 'degenerate art'"?, The Art Newspaper, No 255, March 2014 p 33.

[30] Quotations are from Barron, op cit at 226.

[31] Michael and Linda Hutcheon, “Portrait of the Artist as an Older Man”, in Philip Purvis (ed), Masculinity in Opera, Routledge, New York/London, 2013, at 221.

[32] Goebbels’ speech to the Reichskulturkammer, 6 December 1934.

[33] Hindemith later enjoyed a brief return to official favour, but his independent artistic convictions eventually led to his music being included in the 1938 exhibition of “degenerate” music. He eventually emigrated to the United States. See also Hutcheon, op cit, and sources there cited.

[34] The Altarpiece has also, of course, resonated strongly with artists of other nationalities, acting as a fertile source of inspiration for painters such as Chagall, Picasso and Graham Sutherland: see Aaron Rosen, Imagining Jewish Art: Encounters with the Masters in Chagall, Guston and Kitaj, MHRA, London, 2009, at 32; Apostolos-Cappadona, D, "The Essence of Agony: Grűnewald’s Influence on Picasso", Artibus et Historiae, Vol 13, No 26, 1992 31-47.

[35] From November 2013, during renovations at the Altarpiece's normal home at the Musée Unterlinden, it is being shifted to a nearby Dominican Church where it will be on display until spring 2015: The Art Newspaper, Int edn, October 2013, p 11.

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home

[1A] Among the many thousands of artworks recovered as a result of the Monuments Men's efforts were Leonardo da Vinci's Lady with an Ermine; Michelangelo's Madonna of Bruges; Manet's In the Conservatory; Vermeer's The Astronomer; and Rembrandt's 1645 Self-portrait.

[2] Now a popular tourist attraction in its own right.

[3] Nicholas, op cit at 303.

[4] Nicholas, op cit at 303-4, citing account of Monuments officer Marvin Ross, “Report of visit to Strasbourg 10-17 December, 1944”, US National Archives Washington, Record Group 239/28. Ross was an expert on Byzantine, Russian and 18th century French art: see entry at http://www.monumentsmenfoundation.org.

[5] Ann Stieglitz, “The Reproduction of Agony: Toward a Reception-History of Grünewald’s Isenheim Altar after the First World War”, Oxford Art Journal, Vol 12 No 2 (1989) 87.

[6] Stieglitz, op cit.

[7] Stieglitz, op cit; Keith Moxey, “Impossible Distance: Past and Present in the Study of Dürer and Grünewald”, The Art Bulletin, Vol 86 No 4 (Dec 2004), 750.

[8] Reinhhard Piper, cited in Stieglitz, op cit.

[9] Stieglitz, op cit.

[10] M Kay Flavell, George Grosz: A Biography, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1988, at 225.

[11] Beth Irwin Lewis, George Grosz: Art and Politics in the Weimar Republic. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1991, at 225.

[12] Flavell, op cit at 228.

[13] Flavell, op cit at 68.

[14] Michel White, “Not Another Blasphemy Trial; The Prosecution of George Grosz and Political Justice in Weimer Germany” in Daniel McClean (ed), The Trials of Art, Ridinghorse, London, 2007, at 225.

[15] The sketches were designed as accompaniments for a performance of The Good Solder Schweik.

[16] Reinhold Heller, entry on Otto Dix, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press 2009.

[17] Juliana D Kreinik, The Canvas and the Camera in Weimar Germany, (PhD diss), ProQuest, Ann Arbor, 2008.

[18] This painting has been missing since 1940.

[19] Frédérique Goerig-Hergott, “Otto Dix: Painting to Exorcise War”, at Arts & Societies Seminar Conjuring Away War, 3 March 2013.

[20] Goerig-Hergott, op cit.

[21] Nicholas, op cit at 6. For an account of the Nazi's similar approach to movie films, see Thomas Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler 1933-39, Columbia University Press, New York, 2013.

[22] Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1979, at 8.

[23] Hinz, op cit.

[24] Cited in Nicholas, op cit at 6.

[25] Speech by Hitler on the opening of the Home of German Art, 19 July 1937.

[25A] In November 2013 it was reported that a hoard of over 1,400 works had been discovered in the Munich apartment of Cornelius Gurlitt, the elderly son of a Nazi-era art dealer. Many of the works were by "degenerate" artists such as Dix, Beckmann, Kirchner, Picasso, Matisse, Toulouse-Lautrec, Chagall and Matisse. It is probable that the works were confiscated by the Nazis, or sold under duress as Jewish collectors were forced to unload art at worse than bargain prices: Philip Kennicott, "Works seized by Nazis as 'degenerate' electrify art world", Washington Post, 6 November 2013. For more details, see lootedart.com. For a complete list of confiscated degenerate art, see: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/e/entartete-kunst/

[25B] This was despite the fact that Nolde was himself a long-time Nazi.

[26] Nicholas, op cit at 16; Hinz, ch 1.

[27] Jonathan Petropoulos, Art as Politics in the Third Reich ,University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1996. See also generally Jonathan Petropoulos, The Faustian Bargain: The Art World in Nazi Germany, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000.

[28] Stephanie Barron, “1937: Modern Art and Politics in Prewar Germany”, in Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany, Harry A Abrams/Los Angeles County Museum of Art, New York, 1991, at 226.

[29] See generally Nicholas, op cit, Prologue.

[29A] There are currently unresolved questions over whether German museums have any legal or ethical rights to "degenerate" works that they were forced to deaccession by the Nazis: see Martin Bailey, "What next for 'degenerate art'"?, The Art Newspaper, No 255, March 2014 p 33.

[30] Quotations are from Barron, op cit at 226.

[31] Michael and Linda Hutcheon, “Portrait of the Artist as an Older Man”, in Philip Purvis (ed), Masculinity in Opera, Routledge, New York/London, 2013, at 221.

[32] Goebbels’ speech to the Reichskulturkammer, 6 December 1934.

[33] Hindemith later enjoyed a brief return to official favour, but his independent artistic convictions eventually led to his music being included in the 1938 exhibition of “degenerate” music. He eventually emigrated to the United States. See also Hutcheon, op cit, and sources there cited.

[34] The Altarpiece has also, of course, resonated strongly with artists of other nationalities, acting as a fertile source of inspiration for painters such as Chagall, Picasso and Graham Sutherland: see Aaron Rosen, Imagining Jewish Art: Encounters with the Masters in Chagall, Guston and Kitaj, MHRA, London, 2009, at 32; Apostolos-Cappadona, D, "The Essence of Agony: Grűnewald’s Influence on Picasso", Artibus et Historiae, Vol 13, No 26, 1992 31-47.

[35] From November 2013, during renovations at the Altarpiece's normal home at the Musée Unterlinden, it is being shifted to a nearby Dominican Church where it will be on display until spring 2015: The Art Newspaper, Int edn, October 2013, p 11.

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home