The futurists declare war on pasta

|

By Philip McCouat

What does one make of a twentieth century art movement that glorifies war, gets a kick out of steam locomotives and puts out a cookbook? An art movement that preaches the demolition of museums and libraries? An Italian movement that admires eau de cologne but reviles pasta? |

-------------------------------------------- For more on food and art For more on food and art, see: ------------------------------------------------------ |

Such were the complex and often paradoxical views of the Italian Futurists, a group who inspired admiration, shock, laughter -- and a large dose of outright hostility and derision. In this article we will be focusing on just one of their more surprising exploits – their war against pasta and all it stood for, which in their view, was quite a lot. But first, we need to see just how all this came about.

In the beginning: the Futurist Manifesto

The avant-garde Futurist movement burst onto the international scene on 20 February 1909, with the publication of the Futurist Manifesto, drafted by the Italian millionaire writer, critic and poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti [1].

The Manifesto, cast in deliberately inflammatory and provocative terms, was addressed to “all the living men on earth”. Its themes were revolutionary:

The Manifesto, cast in deliberately inflammatory and provocative terms, was addressed to “all the living men on earth”. Its themes were revolutionary:

- the exaltation of dynamism, audacity, danger, speed, revolt and action

- the glorification of violence, conflict and war (“the sole cleanser of the world”), militarism and the “beautiful ideas that kill”

- opposition to traditional morality

- contempt for “old pictures” (“graves in a cemetery”) and Italy’s cultural stagnation (“we want to demolish museums and libraries” and to “deliver Italy from its gangrene of professors, archaeologists, tourist guides and antiquaries”)

- the celebration of newness, youth, modernity, progress, industry, machines and technology

- a determination to “fight…feminism” and to “glorify…contempt for women”[2], and

- intense Italian chauvinism and nationalism.

Fig 1: Futurism poster

Fig 1: Futurism poster

Many of these themes are neatly encapsulated in Marinetti’s famous comment, “A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath ... a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace” [3].

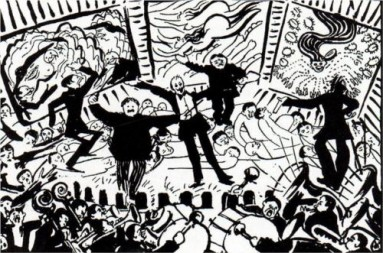

Ultimately, Marinetti and his Italian colleagues wanted to transform art into life. This would necessarily involve entering the public arena in a direct and combative manner. With the typical bravado of the Futurists, they vowed to “introduce the fist into the struggle for art”. This, in their view, would require a total and permanent revolution in all spheres of society [4].

Ultimately, Marinetti and his Italian colleagues wanted to transform art into life. This would necessarily involve entering the public arena in a direct and combative manner. With the typical bravado of the Futurists, they vowed to “introduce the fist into the struggle for art”. This, in their view, would require a total and permanent revolution in all spheres of society [4].

Futurism therefore developed into a wide-ranging and vigorously promoted worldview covering aspects as diverse as architecture, literature, economics, interior decoration, law enforcement, industrial relations, religion, morals, marriage and – as we shall see later – politics. During the period 1909-12, no fewer than thirty manifestos were published setting out how the Futurists aimed to implement their modestly named “re-fashioning of the universe”.

The Futurists’ views were uncompromising and they did not shirk from physical violence when opposing their despised “enemies” or when defending their own position. Marinetti professed to enjoy “the grand tradition of being booed”, reasoning that if he was cheered he was not being challenging enough. He considered that anything that was “applauded immediately was certainly no better than the average intelligence and was something mediocre, dull, regurgitated or too well-digested” [5].

The Futurists’ views were uncompromising and they did not shirk from physical violence when opposing their despised “enemies” or when defending their own position. Marinetti professed to enjoy “the grand tradition of being booed”, reasoning that if he was cheered he was not being challenging enough. He considered that anything that was “applauded immediately was certainly no better than the average intelligence and was something mediocre, dull, regurgitated or too well-digested” [5].

Futurist art and sculpture

line with the Manifesto, the Futurists rejected all art of the past, and promoted a new art that embraced “technology, scientific advance, psychoanalysis and all things modern” -- an art that would be worthy of the new Italy, conditioned by forward-looking dynamism and change [6].

Given their wish to take on the world, it was natural that the first Futurist exhibition was held, not in Italy, but in the world’s art capital, Paris. With a characteristically vigorous marketing campaign, the Futurists met with both admiration and derision. Some of the opinions expressed by their fellow artists were harsh. The Vorticist English artist Wyndham Lewis would comment dismissively in his short-lived magazine, Blast, that “Futurism, as preached by Marinetti, is largely Impressionism up-to-date. To this is added his Automobilism and Nietzsche stunt” [7].

Given their wish to take on the world, it was natural that the first Futurist exhibition was held, not in Italy, but in the world’s art capital, Paris. With a characteristically vigorous marketing campaign, the Futurists met with both admiration and derision. Some of the opinions expressed by their fellow artists were harsh. The Vorticist English artist Wyndham Lewis would comment dismissively in his short-lived magazine, Blast, that “Futurism, as preached by Marinetti, is largely Impressionism up-to-date. To this is added his Automobilism and Nietzsche stunt” [7].

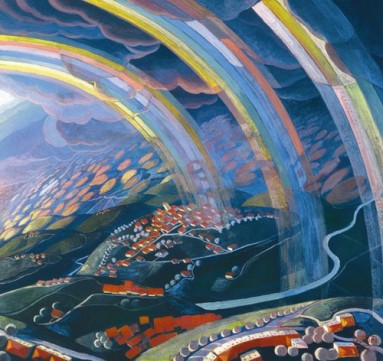

Typical of the Futurists’ work were paintings on subjects such as the dynamic experience of aeroplane flight (Fig 2), a “syntheses of labour, light and movement” (Fig 3) and a dog in motion (Fig 4) [8].

Their experiments also extended to sculpture such as Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (Fig 5).

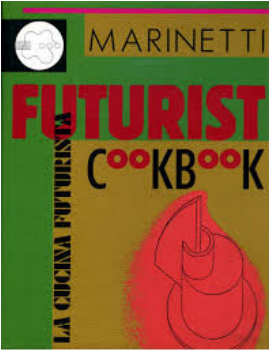

Cuisine as performance art…

One of the more surprising applications of the Futurist philosophy was in the seeming anodyne subject of food. In fact, this had long been an absorbing interest for them, with exotic menus and eccentrically-styled dinners being devised and numerous pamphlets and statements being published [9]. These culminated in Marinetti and Luigi Colombo’s The Manifesto of Futurist Cooking (1930) and reached full expression in Marinetti’s notorious The Futurist Cookbook (1932). Essentially, the Futurists aimed to marry art and gastronomy, to transform dining into a type of performance art. As Lesley Chamberlain has said, “[N]o other cultural movement has produced a provocative work of art disguised as easy-to-read cookbook” [10].

Fig 6: F T Marinetti, The Futurist Cookbook Fig 6: F T Marinetti, The Futurist Cookbook

|

Marinetti proposed that food was not just a background to life, but played a vital part in how people lived and thought. While graciously conceding that “great things have been achieved in the past by men who were poorly fed”, Marinetti stressed that “what we think or dream or do is determined by what we eat and what we drink”. In his view, a mind transformed by modern food was a mind that could be receptive to the modern thinking that Italy so desperately needed.

Ultimately, Marinetti believed, dining would become a purely aesthetic experience, with the actual nutritional part simply a matter of ingesting State-provided nutritional pills or powders, giving men “more leisure time with which to enjoy finer quality, real-food meals” [11]. |

These ideas were put into practice with the opening of the “Tavern of the Holy Palate”, which Marinetti described as not just a simple ordinary restaurant, but as “an arts centre holding competitions and organising Futurist poetry evenings, art exhibitions and fashion shows instead of the usual post-prandial coffee evenings or dances.”

The surroundings and the dishes served at the Holy Palate were designed to put diners in unsettling situations, so as to totally engage their senses and shock them into breaking free from their normal everyday habits and expectations. So, for example, diners could find themselves in an aluminium-lined room where a recording of a Wagner opera was playing, sitting down to a meal consisting of a collection of tiny morsels (such as a single olive) which they were expected to eat while stroking a tactile device of velvet or sandpaper. The atmosphere might be enhanced by ionizers, perfume sprays or ultra violet lights. Marinetti even dreamed of a future when ordinary knives and forks could be dispensed with.

The surroundings and the dishes served at the Holy Palate were designed to put diners in unsettling situations, so as to totally engage their senses and shock them into breaking free from their normal everyday habits and expectations. So, for example, diners could find themselves in an aluminium-lined room where a recording of a Wagner opera was playing, sitting down to a meal consisting of a collection of tiny morsels (such as a single olive) which they were expected to eat while stroking a tactile device of velvet or sandpaper. The atmosphere might be enhanced by ionizers, perfume sprays or ultra violet lights. Marinetti even dreamed of a future when ordinary knives and forks could be dispensed with.

Futurist meals came to be known from their deliberately bizarre combinations, with equally startling and provocative names. For example, Excited Pig consisted of a cooked and peeled whole salami, placed vertically on the plate with coffee sauce mixed with eau de cologne. Chicken Fiat was flavoured with a stuffing of ball bearings, roasted and served with whipped cream. Drum Roll of Colonial Fish comprised poached mullet marinated in milk, liqueur, capers, and red pepper and stuffed with date jam, banana, and pineapple, eaten to a continuous rolling of drums.

Menus were designed to be compatible with special occasions or themes, or could even be served in reverse order. One meal started with coffee and Sweet Memories on Ice, progressed to main courses such as Mummy roast with professorial liver and Explosive peas with the sauce of history, and finished with Clotted-blood soup and an after-dinner, pre-dinner glass of vermouth [12].

Menus were designed to be compatible with special occasions or themes, or could even be served in reverse order. One meal started with coffee and Sweet Memories on Ice, progressed to main courses such as Mummy roast with professorial liver and Explosive peas with the sauce of history, and finished with Clotted-blood soup and an after-dinner, pre-dinner glass of vermouth [12].

Edible food sculptures were also in vogue with the Futurists. In the Manifesto, Marinetti describes Equator + North Pole, a work composed of “an equatorial sea of poached egg yolks seasoned like oysters with pepper, salt and lemon. In the centre emerges a cone of firmly whipped egg white full of orange segments looking like juicy sections of the sun. The peak of the cone is strewn with pieces of black truffle cut in the form of black aeroplanes conquering the zenith”.

… with its roots in the past

Although Futurist cooking is often presented as an entirely novel and bizarre concept, it in fact mirrored aspects of Italian cookbooks that had been published as far back as the 16th century [13].

So, for example, in Cristoforo Messisbugo’s classic 1549 text Banquets, Compositions of Courses and General Table Design [14], a detailed manual for court banquets, “each course had its own particular music or form of spectacle, all perfectly integrated into the serving of the food in a way that we would categorise in modern parlance as a happening” [15]. These banquets might, for example, be preceded by the performance of a farce and a concert. During the meal, musicians and a troop of dancers might appear to enhance the ambiance, while sugar sculptures could provide visual pleasure. Even earlier precedents for Futurist tenets can be found in the Satyricon, particularly in the Futurists’ New Year’s Lunch, in which a live turkey was set free on the table as the diners took their first bites of a cooked one [16].

The design and sequence of these court banquets also played with diners’ expectations in a way that recalls later Futurist “innovations”: on one banquet in 1529, after the scheduled nine elaborate courses, diners would no doubt have been surprised to see that the banquet immediately recommenced from the beginning.

Marinetti’s Cookbook not only draws on the ideas and traditions set out in the Messisbugo’s earlier text, but is even structured in the same way, consisting of a collection of 172 recipes framed within a narrative account of some successful Futurist dinners. But the parallels do not stop there –there was also a more subtle way in which Marinetti hoped to benefit from the earlier tradition, and this lay in its rather surprising political significance.

As Danielle Callegari has suggested, the cookbook in Italy was “first and foremost conceived as subtle but formidable political tool” [17]. So, for example, Messisbugo wrote his book with one eye firmly on his advancement at court, by promoting the status and importance of the master of cuisine. Callegari has pointed out that he was notably successful in this aim – “he was elevated to the level of Count Palatine and retained his impressive power until the end of his life”. Marinetti, it may be surmised, may have hoped to exploit his Futurist Cookbook in a similar way, so as to reaffirm his own place of leadership in the cultural program of Mussolini’s government [18].

So, for example, in Cristoforo Messisbugo’s classic 1549 text Banquets, Compositions of Courses and General Table Design [14], a detailed manual for court banquets, “each course had its own particular music or form of spectacle, all perfectly integrated into the serving of the food in a way that we would categorise in modern parlance as a happening” [15]. These banquets might, for example, be preceded by the performance of a farce and a concert. During the meal, musicians and a troop of dancers might appear to enhance the ambiance, while sugar sculptures could provide visual pleasure. Even earlier precedents for Futurist tenets can be found in the Satyricon, particularly in the Futurists’ New Year’s Lunch, in which a live turkey was set free on the table as the diners took their first bites of a cooked one [16].

The design and sequence of these court banquets also played with diners’ expectations in a way that recalls later Futurist “innovations”: on one banquet in 1529, after the scheduled nine elaborate courses, diners would no doubt have been surprised to see that the banquet immediately recommenced from the beginning.

Marinetti’s Cookbook not only draws on the ideas and traditions set out in the Messisbugo’s earlier text, but is even structured in the same way, consisting of a collection of 172 recipes framed within a narrative account of some successful Futurist dinners. But the parallels do not stop there –there was also a more subtle way in which Marinetti hoped to benefit from the earlier tradition, and this lay in its rather surprising political significance.

As Danielle Callegari has suggested, the cookbook in Italy was “first and foremost conceived as subtle but formidable political tool” [17]. So, for example, Messisbugo wrote his book with one eye firmly on his advancement at court, by promoting the status and importance of the master of cuisine. Callegari has pointed out that he was notably successful in this aim – “he was elevated to the level of Count Palatine and retained his impressive power until the end of his life”. Marinetti, it may be surmised, may have hoped to exploit his Futurist Cookbook in a similar way, so as to reaffirm his own place of leadership in the cultural program of Mussolini’s government [18].

… and with echoes in the present

The food writer Elizabeth David has commented that, considered solely in a culinary sense, Marinetti’s new dishes were often “preposterous”, with most being “founded on the shock principle of combining unsuitable and exotic ingredients”, and a cooking technique that seems to have been “rather sketchy” [19]. However, she concedes that Marinetti “clearly knew something of the history of gastronomy”, and that there was “a good deal of commonsense” in his recognition that “diet and methods of cooking must necessarily evolve at the same time as other habits and customs” [20].

Significantly, David actually includes no fewer than eight of Marinetti’s more moderate recipes in her classic book Italian Cooking. As was typical for Futurist meals, the names of these dishes sound more alarming than they actually were: Divorced eggs, for example, turns out simply to involve a separation of the yoke and egg white; Diabolical roses” consist of velvety red roses cooked in batter (particularly suitable “for brides to eat at midnight, in January”), and Green rice is a straightforward rice dish served with a pea sauce.

Futurist food has also been recognised, despite its obvious excesses, as a real response to the bourgeois coddling of nineteenth century cuisine, and as a forerunner of nouvelle cuisine, with its emphasis on small servings, lighter dishes, and decorative presentation [21]. It also has clear echoes in the exotic cuisine of modern-day celebrity chefs such as Ferran Adrià of elBulli, or Heston Blumenthal, with his analytical questioning of traditional methods, and his unusual pairings of foods based on their molecular structure (such as white chocolate with caviar, or salmon in liquorice gel).

The Futurist Cookbook also foreshadows Blumenthal’s interest in diners’ sensory enrichment – his use of liquid nitrogen to disperse particular aromas during service of the food, or the amplification of sound to enhance the experience of crunching while eating. It is possibly no coincidence that Blumenthal, like Marinetti, has published his own Manifesto on “New Cookery”[22].

One commentator has even surmised that “the current craze for low-carbohydrate meals, so-called functional foods, and cheaply gotten (former) colonial fruits suggests that, were it in business today, the Tavern of the Holy Palate would require that reservations be made a year in advance” [23].

Significantly, David actually includes no fewer than eight of Marinetti’s more moderate recipes in her classic book Italian Cooking. As was typical for Futurist meals, the names of these dishes sound more alarming than they actually were: Divorced eggs, for example, turns out simply to involve a separation of the yoke and egg white; Diabolical roses” consist of velvety red roses cooked in batter (particularly suitable “for brides to eat at midnight, in January”), and Green rice is a straightforward rice dish served with a pea sauce.

Futurist food has also been recognised, despite its obvious excesses, as a real response to the bourgeois coddling of nineteenth century cuisine, and as a forerunner of nouvelle cuisine, with its emphasis on small servings, lighter dishes, and decorative presentation [21]. It also has clear echoes in the exotic cuisine of modern-day celebrity chefs such as Ferran Adrià of elBulli, or Heston Blumenthal, with his analytical questioning of traditional methods, and his unusual pairings of foods based on their molecular structure (such as white chocolate with caviar, or salmon in liquorice gel).

The Futurist Cookbook also foreshadows Blumenthal’s interest in diners’ sensory enrichment – his use of liquid nitrogen to disperse particular aromas during service of the food, or the amplification of sound to enhance the experience of crunching while eating. It is possibly no coincidence that Blumenthal, like Marinetti, has published his own Manifesto on “New Cookery”[22].

One commentator has even surmised that “the current craze for low-carbohydrate meals, so-called functional foods, and cheaply gotten (former) colonial fruits suggests that, were it in business today, the Tavern of the Holy Palate would require that reservations be made a year in advance” [23].

The crusade against pasta

Of all the surprising characteristics of Futurist cooking, one of the most startling, especially in Italy, was its total rejection of pasta. Marinetti regarded pasta as “an absurd Italian gastronomic religion”, and the embodiment of everything that was wrong with the old Italy. According to his Manifesto of Futurist Cooking, pasta was inimical to the modern-thinking person, leaving the eater heavy and shapeless, and inducing “lassitude, pessimism, nostalgic inactivity and neutralism”. Pasta was “anti-virile” and “no food for fighters”.

His view, backed up by some dubious “scientific” evidence, was consistent with a number of his aims – the ending of mediocrity in pleasures of the palate, the abolition of traditional recipes, and the removal of volume and weight as evaluators of food [24].

Other Futurists were equally colourful. Marco Ramperti commented that when “swallowed down the way it is, spaghetti poisons us….. “Our thoughts wind round each other, get mixed up and tangled like the vermicelli we have taken in”[25]. Another described it as “a form of slavery…. It puffs up our cheeks like grotesque masks on a fountain … it nails us to the chair, gorged and stupefied, apoplectic and gasping”[26].

His view, backed up by some dubious “scientific” evidence, was consistent with a number of his aims – the ending of mediocrity in pleasures of the palate, the abolition of traditional recipes, and the removal of volume and weight as evaluators of food [24].

Other Futurists were equally colourful. Marco Ramperti commented that when “swallowed down the way it is, spaghetti poisons us….. “Our thoughts wind round each other, get mixed up and tangled like the vermicelli we have taken in”[25]. Another described it as “a form of slavery…. It puffs up our cheeks like grotesque masks on a fountain … it nails us to the chair, gorged and stupefied, apoplectic and gasping”[26].

Fig 9: Photo of Marinetti easing spaghetti, Biffi restaurant 1930 (Estorick collection). Marinetti later condemned this as a fake photomontage, concocted and disseminated by his enemies.

Fig 9: Photo of Marinetti easing spaghetti, Biffi restaurant 1930 (Estorick collection). Marinetti later condemned this as a fake photomontage, concocted and disseminated by his enemies.

The anti-pasta crusade naturally drew howls of protest and received worldwide publicity -- reactions which were exactly what Marinetti desired. It was extensively reported as far away as Australia, though in terms which were more incredulous than admiring. In far north Queensland, for example, the Morning Bulletin commented that the campaign “sounds about as sensible as starting a Liberation Society in Leeds to remove Yorkshire pudding” [27].

In Italy itself, there was more outright opposition. The housewives in the city of L’Acquila defended their love of spaghetti with a joint letter of protest addressed to Marinetti (how he would have enjoyed that!) and the mayor of Naples, the Duke of Bovino, stoutly defended pasta by pointing to the indisputable fact that the “angels in Paradise eat nothing but vermicelli al pomodoro”, with Marinetti responding that this was precisely why change was needed.

In Italy itself, there was more outright opposition. The housewives in the city of L’Acquila defended their love of spaghetti with a joint letter of protest addressed to Marinetti (how he would have enjoyed that!) and the mayor of Naples, the Duke of Bovino, stoutly defended pasta by pointing to the indisputable fact that the “angels in Paradise eat nothing but vermicelli al pomodoro”, with Marinetti responding that this was precisely why change was needed.

At the time, Marinetti’s campaign may not have reduced pasta consumption one iota, but it was nevertheless successful in advancing his underlying objectives – to obtain publicity, draw out outraged reactions, shake up people’s complacent views and to encourage them to pay more attention to what they were putting in their mouths. Having said that, Marinetti’s excesses did not meet with the approval of some more sober Futurist colleagues. They considered that his pronouncements were “complete foolishness” which no-one could take seriously, and only served to discredit Futurist art [28].

Mussolini, champion of rice, and the Battle for Grain

The Futurists were not the only ones interested in food reform (or in violent tactics). Benito Mussolini, the Fascist leader of Italy, was also vitally interested in changing his subjects’ eating habits, and this policy in some respects fitted neatly with Marinetti’s own anti-pasta fixation. Mussolini’s reasons for this were, however, primarily economic and political.

The main concern for Mussolini was to secure Italy’s self-sufficiency in food, and he vigorously promoted the consumption of foods in which Italy could easily produce, such as rice, grapes and citrus. One of the main problems he faced, however, was that Italy could not produce enough wheat, from which both bread and pasta are made, and which obviously formed a staple part of Italian cuisine, especially in the poorer south.

Mussolini tried to solve this problem in a number of ways, collectively referred to as the Battle for Grain. Firstly, his regime actively encouraged the consumption of rice (more virile and patriotic) instead of pasta. So, for example, a National Rice Board was founded, and official “rice days” were held in which food trucks provided thousands of free samples and recipes. Mussolini’s second strategy was to promote brown bread, which was both cheaper than white bread and required less wheat for its production [29]. His third option was to provide significant incentives for more wheat production [30].

The main concern for Mussolini was to secure Italy’s self-sufficiency in food, and he vigorously promoted the consumption of foods in which Italy could easily produce, such as rice, grapes and citrus. One of the main problems he faced, however, was that Italy could not produce enough wheat, from which both bread and pasta are made, and which obviously formed a staple part of Italian cuisine, especially in the poorer south.

Mussolini tried to solve this problem in a number of ways, collectively referred to as the Battle for Grain. Firstly, his regime actively encouraged the consumption of rice (more virile and patriotic) instead of pasta. So, for example, a National Rice Board was founded, and official “rice days” were held in which food trucks provided thousands of free samples and recipes. Mussolini’s second strategy was to promote brown bread, which was both cheaper than white bread and required less wheat for its production [29]. His third option was to provide significant incentives for more wheat production [30].

Marinetti and Fascism

Given his views on war, nationalism and violence, it was not surprising that Marinetti became closely associated with Mussolini and with fascism. In 1918, Marinetti played a leading role in the formation of the Futurist Political Party (Fasci Politici Futuristi), with an eclectic platform that included calls for an eight-hour day, equal pay for women [31], expulsion of the Pope, compulsory gymnastics, extensive nationalisation of land to be redistributed to war veterans, heavy wealth taxes, easy divorce and free love [32]. Many of its members were war veterans.

This Party later merged with Mussolini’s to form the Italian Fascist Party, and Marinetti went on to co-author its first manifesto. The party, however, with both Mussolini and Marinetti included in its candidates, performed miserably in the 1919 Italian elections [33]. Marinetti was chastened by the defeat, and withdrew from the party in 1920, on the grounds that it overly embraced the conservative past, and that Mussolini’s emerging policies could harm the Futurists’ reputation amongst the working class.

Although Marinetti maintained close links with Fascism, he gradually began disengaging from its political side, preferring to concentrate on the less confrontationist issue of achieving the cultural pre-eminence of Futurism in the field of art. Even here, however, problems developed from 1937, as powerful right wing hardliners in the regime began cracking down hard on artistic freedoms, and in 1939 shut down the Futurist newspaper Artecrazia altogether.

Reflecting these shifts, Marinetti’s personal association to Mussolini was complex, varying from issue to issue, and was more like a series of one-night stands than a steady marriage of views. So, for example, at the time before Marinetti’s withdrawal in 1920, Mussolini described him as “an eccentric buffoon” whom no-one took seriously [34], while Marinetti retaliated that Mussolini was a “megalomaniac who will little by little become a reactionary” [35]. Yet later, although rejecting Marinetti’s overtures to make Futurism the official state-approved art of Italy, Mussolini warmly described Marinetti as “my dear old fried of the first Fascist battles”, in a letter ostentatiously reproduced by Marinetti in the Cookbook. Mussolini also agreed, on Marinetti’s intervention, to forbid the Nazis’ travelling exhibition that mocked “Degenerate Art” to tour in Italy when it became likely that the Nazis would include Futurist works as degenerate [36].

Even on the specific issue of pasta, their agreement was only partial. Marinetti made specific mention in the Cookbook that his own anti-pasta views chimed with the government policy, reminding his readers that the abolition of pasta would “free Italy from expensive foreign grains and promote the Italian rice industry”. But although Mussolini favoured a reduction in pasta consumption for that very reason, he was careful not to call for an outright ban, as Marinetti had. He was too well aware of its traditional fundamental role in Italian life, and did not have Marinetti’s freedom to snub his nose at the people on whom he depended for power [37].

This Party later merged with Mussolini’s to form the Italian Fascist Party, and Marinetti went on to co-author its first manifesto. The party, however, with both Mussolini and Marinetti included in its candidates, performed miserably in the 1919 Italian elections [33]. Marinetti was chastened by the defeat, and withdrew from the party in 1920, on the grounds that it overly embraced the conservative past, and that Mussolini’s emerging policies could harm the Futurists’ reputation amongst the working class.

Although Marinetti maintained close links with Fascism, he gradually began disengaging from its political side, preferring to concentrate on the less confrontationist issue of achieving the cultural pre-eminence of Futurism in the field of art. Even here, however, problems developed from 1937, as powerful right wing hardliners in the regime began cracking down hard on artistic freedoms, and in 1939 shut down the Futurist newspaper Artecrazia altogether.

Reflecting these shifts, Marinetti’s personal association to Mussolini was complex, varying from issue to issue, and was more like a series of one-night stands than a steady marriage of views. So, for example, at the time before Marinetti’s withdrawal in 1920, Mussolini described him as “an eccentric buffoon” whom no-one took seriously [34], while Marinetti retaliated that Mussolini was a “megalomaniac who will little by little become a reactionary” [35]. Yet later, although rejecting Marinetti’s overtures to make Futurism the official state-approved art of Italy, Mussolini warmly described Marinetti as “my dear old fried of the first Fascist battles”, in a letter ostentatiously reproduced by Marinetti in the Cookbook. Mussolini also agreed, on Marinetti’s intervention, to forbid the Nazis’ travelling exhibition that mocked “Degenerate Art” to tour in Italy when it became likely that the Nazis would include Futurist works as degenerate [36].

Even on the specific issue of pasta, their agreement was only partial. Marinetti made specific mention in the Cookbook that his own anti-pasta views chimed with the government policy, reminding his readers that the abolition of pasta would “free Italy from expensive foreign grains and promote the Italian rice industry”. But although Mussolini favoured a reduction in pasta consumption for that very reason, he was careful not to call for an outright ban, as Marinetti had. He was too well aware of its traditional fundamental role in Italian life, and did not have Marinetti’s freedom to snub his nose at the people on whom he depended for power [37].

Conclusion

The Futurist experiment, ill-fated since the 1937 crackdown, fizzled out with Marinetti’s death in 1944. Until recently [38], its innovations have tended to be obscured by his strong associations with Fascism, exaggerated machismo and often-preposterous excesses. But, in artistic terms, it is hard not to be impressed by the original creative spirit and energy that went into many of the Futurist paintings and sculptures – works which may ultimately have had some influence on movements such as Dadaism and Surrealism. In the same way, the excesses of the Futurist philosophy of food should not obscure the fact that many of their ideas have belatedly found echoes in the more innovative reaches of modern day cuisine.

© Philip McCouat 2014

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The Futurists declare war on pasta", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

© Philip McCouat 2014

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The Futurists declare war on pasta", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

end notes

[1] The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism, published on the front page of Le Figaro, 20 February 1909.

[2] See later, end note [31].

[3] Considering the extent to which our present age has become obsessed with the car and with technology in general, this 1909 statement seems more prescient today than it did when it was first made.

[4] Gunter Berghaus, introduction to F T Marinetti, Critical Writings, Farrer, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2006.

]5] Richard Jensen, “Futurism and Fascism”, History Today, Vol 45 No 11, p 35.

[6] David Piper, The Illustrated History of Art, Bounty Books, London 2005 at 400.

[7] Wyndham Lewis, “The Medodrama of Modernity”, Blast, Issue 1 (1914) at 143.

[8] Other prominent early Futurists were Carlo Carrà and Luigi Russolo.

[9] Notably, by the Frenchman Jules Maincave.

[10] Lesley Chamberlain, Introduction to The Futurist Cookbook, by F T Marinetti, transl Suzanne Brill, Bedford Arts, San Francisco, 1989 at 12.

[11] Danielle Callegari, “The Politics of Pasta: La Cucina Futuristica and the Italian Cookbook in History”, California Italian Studies vol 4 No 2 (2013).

[12] Callegari, op cit.

[13] My discussion of this aspect is based largely on Callegari, op cit.

[14] In Italian, Banchetti, Composizioni de vivande et apparecchio generale.

[15] Roy Strong, Feast: A History of Grand Eating, Jonathan Cape, London, 2002 at 130, cited in Callegari.

[16] Callegari, op cit.

[17] Callegari, op cit.

[18] For a discussion of other chefs who published recipe collections as a “stepping stone towards greatness”, see Callegari, op cit.

[19] Elizabeth David, Italian Food, Penguin Books, Hammondsworth, 1963, at 93 and 246.

[20] David, op cit at 94.

[21] Callegari, op cit.

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heston_Blumenthal#Statement_on_the_'New_Cookery'

[23] Christine Baumgarthuber, “Red Holidays of Genius” https://thenewinquiry.com/blog/red-holidays-of-genius/

[24] Callegari, op cit.

[25] Baumgarthuber, op cit.

[26] Carol Helstovsky, Garlic and Oil: Food and Politics in Italy, Berg, Oxford, 2004 at 78-9.

[27] “Re-enter Marinetti”, Rockhampton Morning Bulletin, 2 February 1931, p 8.

[28] Callegari, op cit.

[29] Helstovsky, op cit at 74: Carole Counihan, Around the Tuscan Table: Food, Family and Gender in 20th Century Florence, Routledge, New York, 2004 at 45-6. Mussolini was well aware of the political importance of ensuring supplies of cheap bread – an issue which had evidently contributed to bringing down Francesco Saverio Nitti’s short-lived prime ministry in 1920..

[30] The campaign had decidedly mixed results: Helstovsky, op cit at 81; Counihan, op cit at 46.

[31] As we have seen, the original Futurist Manifesto actually advocated contempt towards women. For the Futurists, at least in theory, sensuality was directed more at machines (“[W]e went up to the three snoring machines to caress their breasts” ... “I savoured a mouthful of strengthening muck which recalled the black teat of my Sudanese nurse”). Marinetti later argued that he was not against women as such; rather, he opposed the set of qualities which, he said, were traditionally associated with them, or imposed upon them -- fragile, romantic, soft, perfumed, providers of love, divine, obsessive, fairy-like and so on. In contrast, he regarded female agitators such as the English suffragettes [cross refer] as “our best allies” (Marinetti, Against Amore and Parliamentarianism). It is also worth pointing out that, at a time when women were almost completely excluded both from mainstream journalism and avant-garde reviews, Marinetti published the poetry of roughly fifty women in his journal Poesia: Walter L Adamson, “Futurism, Mass Culture, and Women: The Reshaping of the Artistic Vocation, 1909-1920”, Modernism/Modernity, 4.1 (1997) 89-114.

[32] Jensen, op cit.

[33] Mussolini eventually came to power in Italy in 1922.

[34] Jensen, op cit.

[35] Berghaus, op cit.

[36] As a matter of interest, it also appears that Marinetti intervened with Mussolini to prevent Nazi-style anti-Semitism in Italy: see Berghaus, op cit.

[37] Helstovsky, op cit at 37.

[38] There has certainly been a recent revival of interest, with a series of major exhibitions devoted to them, including the Tate Modern in 2009 and the Guggenheim in 2014.

© Philip McCouat 2014

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The Futurists declare war on pasta", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

[2] See later, end note [31].

[3] Considering the extent to which our present age has become obsessed with the car and with technology in general, this 1909 statement seems more prescient today than it did when it was first made.

[4] Gunter Berghaus, introduction to F T Marinetti, Critical Writings, Farrer, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2006.

]5] Richard Jensen, “Futurism and Fascism”, History Today, Vol 45 No 11, p 35.

[6] David Piper, The Illustrated History of Art, Bounty Books, London 2005 at 400.

[7] Wyndham Lewis, “The Medodrama of Modernity”, Blast, Issue 1 (1914) at 143.

[8] Other prominent early Futurists were Carlo Carrà and Luigi Russolo.

[9] Notably, by the Frenchman Jules Maincave.

[10] Lesley Chamberlain, Introduction to The Futurist Cookbook, by F T Marinetti, transl Suzanne Brill, Bedford Arts, San Francisco, 1989 at 12.

[11] Danielle Callegari, “The Politics of Pasta: La Cucina Futuristica and the Italian Cookbook in History”, California Italian Studies vol 4 No 2 (2013).

[12] Callegari, op cit.

[13] My discussion of this aspect is based largely on Callegari, op cit.

[14] In Italian, Banchetti, Composizioni de vivande et apparecchio generale.

[15] Roy Strong, Feast: A History of Grand Eating, Jonathan Cape, London, 2002 at 130, cited in Callegari.

[16] Callegari, op cit.

[17] Callegari, op cit.

[18] For a discussion of other chefs who published recipe collections as a “stepping stone towards greatness”, see Callegari, op cit.

[19] Elizabeth David, Italian Food, Penguin Books, Hammondsworth, 1963, at 93 and 246.

[20] David, op cit at 94.

[21] Callegari, op cit.

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heston_Blumenthal#Statement_on_the_'New_Cookery'

[23] Christine Baumgarthuber, “Red Holidays of Genius” https://thenewinquiry.com/blog/red-holidays-of-genius/

[24] Callegari, op cit.

[25] Baumgarthuber, op cit.

[26] Carol Helstovsky, Garlic and Oil: Food and Politics in Italy, Berg, Oxford, 2004 at 78-9.

[27] “Re-enter Marinetti”, Rockhampton Morning Bulletin, 2 February 1931, p 8.

[28] Callegari, op cit.

[29] Helstovsky, op cit at 74: Carole Counihan, Around the Tuscan Table: Food, Family and Gender in 20th Century Florence, Routledge, New York, 2004 at 45-6. Mussolini was well aware of the political importance of ensuring supplies of cheap bread – an issue which had evidently contributed to bringing down Francesco Saverio Nitti’s short-lived prime ministry in 1920..

[30] The campaign had decidedly mixed results: Helstovsky, op cit at 81; Counihan, op cit at 46.

[31] As we have seen, the original Futurist Manifesto actually advocated contempt towards women. For the Futurists, at least in theory, sensuality was directed more at machines (“[W]e went up to the three snoring machines to caress their breasts” ... “I savoured a mouthful of strengthening muck which recalled the black teat of my Sudanese nurse”). Marinetti later argued that he was not against women as such; rather, he opposed the set of qualities which, he said, were traditionally associated with them, or imposed upon them -- fragile, romantic, soft, perfumed, providers of love, divine, obsessive, fairy-like and so on. In contrast, he regarded female agitators such as the English suffragettes [cross refer] as “our best allies” (Marinetti, Against Amore and Parliamentarianism). It is also worth pointing out that, at a time when women were almost completely excluded both from mainstream journalism and avant-garde reviews, Marinetti published the poetry of roughly fifty women in his journal Poesia: Walter L Adamson, “Futurism, Mass Culture, and Women: The Reshaping of the Artistic Vocation, 1909-1920”, Modernism/Modernity, 4.1 (1997) 89-114.

[32] Jensen, op cit.

[33] Mussolini eventually came to power in Italy in 1922.

[34] Jensen, op cit.

[35] Berghaus, op cit.

[36] As a matter of interest, it also appears that Marinetti intervened with Mussolini to prevent Nazi-style anti-Semitism in Italy: see Berghaus, op cit.

[37] Helstovsky, op cit at 37.

[38] There has certainly been a recent revival of interest, with a series of major exhibitions devoted to them, including the Tate Modern in 2009 and the Guggenheim in 2014.

© Philip McCouat 2014

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The Futurists declare war on pasta", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME