Rose-Marie Ormond

Sargent’s muse and “the most charming girl that ever lived”

By Philip McCouat For comments on this article, see here

Introduction

It was Good Friday, 29 March 1918. A German shell, fired from a newly-developed super gun, crashed high into the stone roof and walls of the Church of St Gervais in Paris, causing it to collapse, killing dozens of French civilians. It would prove to be a futile act ~ within a few months, the war would end with the defeat of the German forces. But the bitter legacy of the attack would live on.

In this article, we look at how this event shaped the intertwined lives and fortunes of just two of the people affected. The first was the celebrated American painter John Singer Sargent, the other his niece Rose-Marie Ormond, the model for some of the most famous of Sargent’s paintings and the person whom he described as “the most charming girl that ever lived”[1].

In this article, we look at how this event shaped the intertwined lives and fortunes of just two of the people affected. The first was the celebrated American painter John Singer Sargent, the other his niece Rose-Marie Ormond, the model for some of the most famous of Sargent’s paintings and the person whom he described as “the most charming girl that ever lived”[1].

A master of the society portrait

John Singer Sargent was born in 1856, at a time when his ever-travelling American parents were staying in Florence. He was educated and trained in Paris and, after experimenting with landscapes, turned to the more lucrative field of portraiture, where he showed exceptional drive and promise. He gained multiple commissions and quickly built a highly successful career, painting portraits of the rich, privileged and famous, and exhibiting regularly at the Paris Salon. He impressed with the confidence of his brushstrokes, often experimenting with unusual compositions and lighting effects, though the suggestively-plunging décolletage of his infamous Portrait of Madame X (1884) caused a largely unfavourable reaction (though remaining one of his all-time personal favourites). He later based himself in London, often travelling to Europe and the Middle East and the United States. His output was enormous, but his seemingly-effortless versatility, not to mention his success, prompted resentment from some fellow artists and critics.

Sargent’s sojourns in the Alps

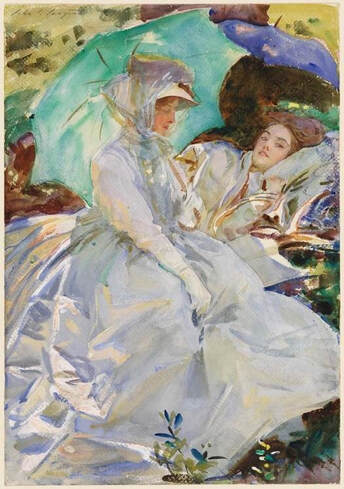

Despite his success, by the early years of the 20th century Sargent was feeling jaded by the constant demands of portraiture. His portraits had begun to lose their appeal for him – he described them dismissively as “picture[s] with a little something wrong about the mouth”[2]. Instead, he started moving in a different direction, one in which he could follow his own preferences. He began spending his summers and autumns in the scenic European Alps with a group of fellow painters, relatives and friends, painting prolifically outdoors during the day -- with the non-painters often assisting as models -- and dining convivially at night. Instead of portraits, these paintings were typically rapidly-worked watercolour landscapes with one or more figures, in relaxed (but carefully posed) postures.

Although not himself married, Sargent had by this stage become the de facto head of his extended family and he made a particular point of including his sisters Emily and Violet on these annual idyllic sojourns. Violet also brought her children Rose-Marie and Reine, who had effectively been brought up by their French-speaking Swiss grandmother, so these get-togethers were the closest they got to a normal family life.

Although not himself married, Sargent had by this stage become the de facto head of his extended family and he made a particular point of including his sisters Emily and Violet on these annual idyllic sojourns. Violet also brought her children Rose-Marie and Reine, who had effectively been brought up by their French-speaking Swiss grandmother, so these get-togethers were the closest they got to a normal family life.

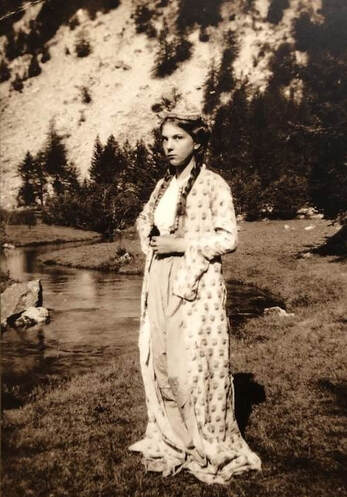

For the children, these holidays were great adventures, often posing in exotic oriental costumes -- specially brought by Sargent for the occasion -- hiking in the woods, gathering strawberries, even keeping inquisitive cows away from the painters [3]. Rose-Marie in particular showed an aptitude for modelling. Even at age 13 she was attractive and poised, and remarkably mature. She quickly became one of Sargent’s favourite subjects, featuring in many of his paintings.

While not conventionally beautiful, Rose-Marie seemed to radiate a warm and bright personality and, as Karen Corsano has noted, more than any of Sargent’s other amateur models, she seemed to strikingly interact with the viewer ~ quick to laugh, a girl with a warm, connecting gaze [4]. Sargent treasured her as much for her sparkling character as for her qualities as a model. She would eventually be his model for seven years.

As Rose-Marie reached her later teens, Sargent did some more studied paintings featuring her (Fig 5). In 1912, he finally executed a formal portrait of her, then aged 19, the only one of his paintings that actually bears her name (Fig 6). As Corsano observes, for the last few years Sargent had documented Rose-Marie’s charm as she bloomed, and here he proudly displayed his muse as her own adult person [5]. As it happened, however, it would prove to be one of the last paintings he ever did of her.

Rose-Marie: the fortunes of love and war

At 19, Rose-Marie was nearing the end of her days as Sargent’s model. About this time, she met up with Robert André-Michel, a distant cousin by marriage. Robert, ten years older than her, but with a similar privileged and cultured background, was a rising academic star as a medieval historian and archivist. His father André had himself been an artist and had become an eminent art historian, who many years before had been an appreciative reviewer of Sargent’s early work, including the controversial Madame X, praising Sargent’s great audacity, extraordinary gift for life and marvellous ability [6].

Rose-Marie and Robert’s relationship deepened and, with the benefit of some behind-the-scenes family matchmaking, they married in August 1913 and settled in Paris. It was an ideal love match. In a letter to her brother Guillaume, Rose-Marie wrote “[the] more I see Robert, the more I see the beauty, the nobleness and the kindness of his heart. Never I saw life so shining and bright, that is the great secret of love” [7].

Rose-Marie and Robert’s relationship deepened and, with the benefit of some behind-the-scenes family matchmaking, they married in August 1913 and settled in Paris. It was an ideal love match. In a letter to her brother Guillaume, Rose-Marie wrote “[the] more I see Robert, the more I see the beauty, the nobleness and the kindness of his heart. Never I saw life so shining and bright, that is the great secret of love” [7].

Just one year later, however, the War broke out. Robert, who had a military background. enlisted immediately as a sergeant, and was sent to the war zone. After only six weeks of war, the carnage was terrible, and he was only too aware of what might lie ahead. On his way to the front, he had pondered on the things that were important to him, writing that "I think gratefully about my beloved wife, about all the happiness she has given me for a year now, about France, about those who have died… about those who are going to die, happy, for the loveliest Fatherland”.

Both Robert and Rose-Marie felt deeply about the nobility of the cause and their duty to France. On 2 October 1914, Robert wrote in his Journal, “I would willingly die to make France greater, more beautiful, more worthy of her secular genius, less attached to base interests, to egotistical pleasures. It is for the ideal France that I fight, for the France of Saint-Louis, of Joan of Arc, of Henry 1V, of the Revolution… for the France we wish to regenerate today: a peaceful France, her hands weaving the France of a new age” [8].

Just 11 days after writing these words, Robert was killed at Soissons, shot in the heart in an intense firefight as he was leading a group of reinforcements over open ground toward the front line.

Both Robert and Rose-Marie felt deeply about the nobility of the cause and their duty to France. On 2 October 1914, Robert wrote in his Journal, “I would willingly die to make France greater, more beautiful, more worthy of her secular genius, less attached to base interests, to egotistical pleasures. It is for the ideal France that I fight, for the France of Saint-Louis, of Joan of Arc, of Henry 1V, of the Revolution… for the France we wish to regenerate today: a peaceful France, her hands weaving the France of a new age” [8].

Just 11 days after writing these words, Robert was killed at Soissons, shot in the heart in an intense firefight as he was leading a group of reinforcements over open ground toward the front line.

Nurse to the blinded

On receiving the shattering news, Rose-Marie moved in with Robert’s equally-stricken parents André and Hélène. Rose-Marie wrote, “My great duty at present, which is my greatest comfort too, is to be to my poor parents-in-law, with whom I suffer so much, a son and a daughter together. Nobody in the world could approach to what Robert was, but in the wife of their son, they will find all the love I can give them”. Sargent, who admired Robert, wrote to her, “Ma chère Rose Marie, I pity you with all my heart – your sorrow must be dreadful…” [9].

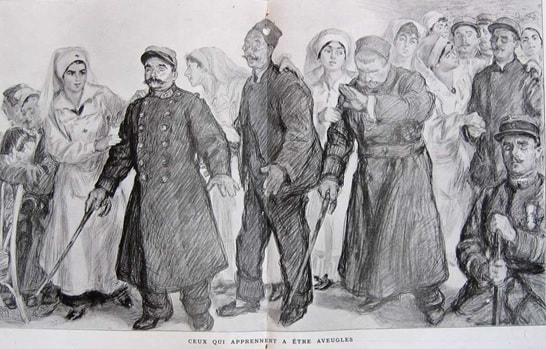

Rose-Marie had originally volunteered for service with the Red Cross when Robert enlisted, but she felt that with Robert gone, she needed to commit more fully to the war effort. Accordingly, in 1915 she joined the nursing staff at the newly-established rehabilitation hospital at Reuilly, dedicated to treating soldiers who had been blinded by armaments or mustard gas. It proved to arduous work, but very fulfilling.

At Reuilly, the nurses carried out normal nursing care, but also helped the inmates with the daily skills which the men had to relearn by touch, such as washing, shaving and eating. They would also read to them privately any personal letters, and keep them in touch with the daily news [10]. As well as the nurses, volunteers also instructed the men with the work skills that might help them get jobs later – typing, printing, cobbling, barrel-making, massage, brush-making, switchboard operating, reading Braille. By the end of the War, still three years away, there were seventeen branches of the School of Reuilly throughout France.

Rose-Marie had originally volunteered for service with the Red Cross when Robert enlisted, but she felt that with Robert gone, she needed to commit more fully to the war effort. Accordingly, in 1915 she joined the nursing staff at the newly-established rehabilitation hospital at Reuilly, dedicated to treating soldiers who had been blinded by armaments or mustard gas. It proved to arduous work, but very fulfilling.

At Reuilly, the nurses carried out normal nursing care, but also helped the inmates with the daily skills which the men had to relearn by touch, such as washing, shaving and eating. They would also read to them privately any personal letters, and keep them in touch with the daily news [10]. As well as the nurses, volunteers also instructed the men with the work skills that might help them get jobs later – typing, printing, cobbling, barrel-making, massage, brush-making, switchboard operating, reading Braille. By the end of the War, still three years away, there were seventeen branches of the School of Reuilly throughout France.

Paul Renouard, an artist who chronicled French life, depicted this scene from the hospital in his etching Those Who Are Learning to be Blind (Fig 9). A line of stricken soldiers from various Allied countries are tentatively walking, holding walking sticks, attended by nurses. We can see Rose-Marie, third nurse from the left, attending a Serbian soldier who is vainly trying to see his hand which he is holding right in front of his face.

With breaks away for sickness and convalescence, including a bout of typhoid fever, Rose-Marie continued on at Reuilly with the “blind soldiers who are filling dearly my days”. She also found solace in her close relationships with friends and relatives, and in music: she was herself a talented pianist, and became a regular concert goer. With much of France being under German control, and a war front that was at times unnervingly close to Paris, Rose-Marie found music to be least a temporary respite from the daily fear of attack and food shortages that were being experienced by the city’s inhabitants.

With breaks away for sickness and convalescence, including a bout of typhoid fever, Rose-Marie continued on at Reuilly with the “blind soldiers who are filling dearly my days”. She also found solace in her close relationships with friends and relatives, and in music: she was herself a talented pianist, and became a regular concert goer. With much of France being under German control, and a war front that was at times unnervingly close to Paris, Rose-Marie found music to be least a temporary respite from the daily fear of attack and food shortages that were being experienced by the city’s inhabitants.

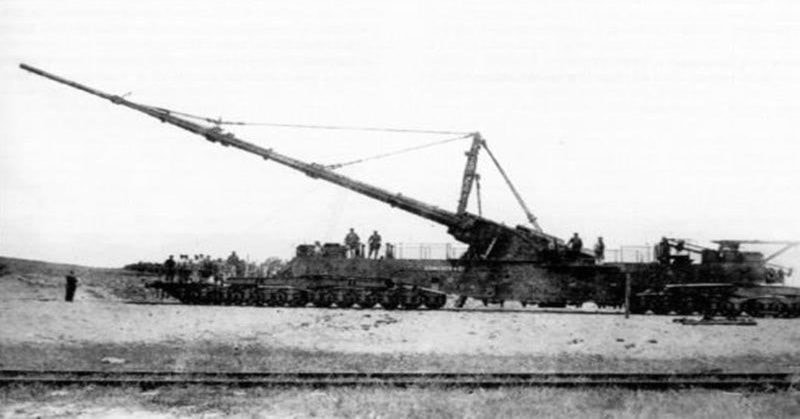

The Good Friday attack and the Paris Gun

In late 1917, the United States declared war against Germany, a crucial development that promised to provide a decisive benefit to the struggling Allied forces. In March 1918, the German armies launched a major new offensive in France, hoping to end the war before the increasing influx of US soldiers could tip the balance in favour of the Allies. Paris became a particular target for German bombardment, which was aimed, not at military or strategic targets, but at demoralising the population by killing civilians in public places. To achieve this aim, the Germans introduced the revolutionary new “Paris Gun”, which had been under development since 1916. With its monstrous barrel over 100 feet (30 metres) long, it dwarfed all other previous super guns such as Big Berthas. Its range was an extraordinary 70 miles (120 kilometres) [11].

In a massive engineering and transport effort, a number of these guns were installed in bomb proof shelters on the hillside of Mont de Joie, 69 miles from the central square of Notre Dame Cathedral. The first shells started to be fired on Saturday 23 March and continued for three days. The extreme range meant that nothing specific could be targeted, so the results of the shelling were to a large extent quite random. Over the three days, there was a total of 58 strikes, hitting places such as a Metro station and a local church, and killing 26 people with about 80 wounded. While terrifying to those affected, it was not destruction on the scale that the Germans were hoping for.

Troubles were also being experienced with the guns. Of the three to be used, one had rapidly worn out, and another blew up, killing five of its crew. But after a few days’ pause to regroup, a third gun was finally ready.

In a massive engineering and transport effort, a number of these guns were installed in bomb proof shelters on the hillside of Mont de Joie, 69 miles from the central square of Notre Dame Cathedral. The first shells started to be fired on Saturday 23 March and continued for three days. The extreme range meant that nothing specific could be targeted, so the results of the shelling were to a large extent quite random. Over the three days, there was a total of 58 strikes, hitting places such as a Metro station and a local church, and killing 26 people with about 80 wounded. While terrifying to those affected, it was not destruction on the scale that the Germans were hoping for.

Troubles were also being experienced with the guns. Of the three to be used, one had rapidly worn out, and another blew up, killing five of its crew. But after a few days’ pause to regroup, a third gun was finally ready.

Meanwhile, reports of the shelling had naturally caused considerable unease and outrage among the Parisians. A warning system was organised ~ to warn residents that bombs were landing in their area, policemen on the street would beat a drum and blow their whistles. This was, of course, totally ineffective and was greeted with public derision. André Michel urged Rose-Marie to take an Easter holiday out of the bombarded city, but she declined. With her love of music, she was keen to attend a Good Friday concert of 16th century motets and responsories, to be performed at the Church of St Gervais, in the Hotel de Ville quarter. After lunching with André and Hélène, she set off to St Gervais in high spirits [12].

Back on the Mont de Joie, firing had resumed, with results from the third gun looking promising for the attackers. Its first two shells landed in the Paris suburbs. Its third shell, fired at an angle of 50 degrees, left the muzzle at a speed of 5,500 feet per second and within 90 seconds had reached its highest altitude of 24 miles. Another 90 seconds of silent flight later, it “struck almost vertically and exploded with a frightening crash”. The shell had hit “like a tremendous thunderclap” high up on the Church of St Gervais, just before the Good Friday concert was about to start [13].

Fifty tons of a limestone blocks, mortar and plaster crashed down, creating carnage among the concertgoers crowded below. An eyewitness reported “acrid black smoke fills the church, we hear shouts, groans, cries of fear, but it is impossible to make anything out, the air is so full of dust and powder. I was blinded, and it was only after several minutes that I was able to see again. Then a heart-rending spectacle, all around us were sprawling bodies, ragged parts of corpses, the wounded dripping blood, a turmoil of wretched people searching for each other in all the sorrow, all the pain of their own catastrophe” [14].

Back on the Mont de Joie, firing had resumed, with results from the third gun looking promising for the attackers. Its first two shells landed in the Paris suburbs. Its third shell, fired at an angle of 50 degrees, left the muzzle at a speed of 5,500 feet per second and within 90 seconds had reached its highest altitude of 24 miles. Another 90 seconds of silent flight later, it “struck almost vertically and exploded with a frightening crash”. The shell had hit “like a tremendous thunderclap” high up on the Church of St Gervais, just before the Good Friday concert was about to start [13].

Fifty tons of a limestone blocks, mortar and plaster crashed down, creating carnage among the concertgoers crowded below. An eyewitness reported “acrid black smoke fills the church, we hear shouts, groans, cries of fear, but it is impossible to make anything out, the air is so full of dust and powder. I was blinded, and it was only after several minutes that I was able to see again. Then a heart-rending spectacle, all around us were sprawling bodies, ragged parts of corpses, the wounded dripping blood, a turmoil of wretched people searching for each other in all the sorrow, all the pain of their own catastrophe” [14].

In total, 91 people, mainly women, were killed, and 68 wounded. The US Ambassador reported that “the destruction wrought by this shell was probably not equalled by any single discharge of any hostile gun in the cruelty and horrors of its results” [15]. Many of the dead were unrecognisable. Some had to be identified by engravings in their wedding rings. Among them was Rose-Marie. She was just 24.

The news shattered André and Hélène. They had now lost both their son and their beloved daughter-in-law, both young, both taken by the war. In Boston, Sargent was told the news by cablegram, and was devastated. “I can’t tell you how sorry I am… and how I feel the loss of the most charming girl who ever lived” he replied to André. That evening he told a friend the news: “It was Rose-Marie…. She was very young and one of the most beautiful and attractive women I ever knew”. As the friend commented, “this meant much from him” [16].

The news shattered André and Hélène. They had now lost both their son and their beloved daughter-in-law, both young, both taken by the war. In Boston, Sargent was told the news by cablegram, and was devastated. “I can’t tell you how sorry I am… and how I feel the loss of the most charming girl who ever lived” he replied to André. That evening he told a friend the news: “It was Rose-Marie…. She was very young and one of the most beautiful and attractive women I ever knew”. As the friend commented, “this meant much from him” [16].

The blinded soldiers in Sargent’s Gassed

The loss of Rose-Marie in the Good Friday attack affected Sargent deeply – and just how deeply is clearly reflected in the major works he created in the aftermath of the War.

Shortly after Rose-Marie died, Sargent was contacted by the British Department of Information, asking if he would accept a commission to go to France as a war artist, along with British artists such as Muirhead Bone, Sir John Lavery and Paul Nash. The request was backed up by a letter from the Prime Minister himself, Lloyd George.

Sargent was totally ignorant of military affairs, and was painfully aware that this new project would be quite different from his previous output of society portraits and idyllic watercolours. But, with recent tragic events, he now seemed to have a new sense of purpose, and accepted. He arrived at General Haig’s headquarters in France, ever dapper, “in the most faultless Khaki, Sam Brown belt under his armpit, puttees etc and Saratoga trunk upon trunk filled with his trousseau”[17].

Sargent visited the war front a number of times, and completed numerous paintings and sketches, but struggled to find a subject for the major work that was expected of him. Finally, in August 1918, it came to him. He was at a casualty dressing station, with fellow artist Henry Tonks, who described the scene: “Gassed cases kept coming in…They sat or lay down on the grass, there must have been several hundred, evidently suffering a great deal… Sargent was very struck by the scene and immediately made a lot of notes”. For Sargent, it was harrowing, the most moving scene in his war experience. This was hardly surprising, given his memory of Rose-Marie’s work with similarly-afflicted men. As Corsano comments, these eye-bandaged, blinded soldiers must have visually recreated for him the blinded soldiers to whom Rose-Marie had dedicated the last years of her life [18].

Shortly after Rose-Marie died, Sargent was contacted by the British Department of Information, asking if he would accept a commission to go to France as a war artist, along with British artists such as Muirhead Bone, Sir John Lavery and Paul Nash. The request was backed up by a letter from the Prime Minister himself, Lloyd George.

Sargent was totally ignorant of military affairs, and was painfully aware that this new project would be quite different from his previous output of society portraits and idyllic watercolours. But, with recent tragic events, he now seemed to have a new sense of purpose, and accepted. He arrived at General Haig’s headquarters in France, ever dapper, “in the most faultless Khaki, Sam Brown belt under his armpit, puttees etc and Saratoga trunk upon trunk filled with his trousseau”[17].

Sargent visited the war front a number of times, and completed numerous paintings and sketches, but struggled to find a subject for the major work that was expected of him. Finally, in August 1918, it came to him. He was at a casualty dressing station, with fellow artist Henry Tonks, who described the scene: “Gassed cases kept coming in…They sat or lay down on the grass, there must have been several hundred, evidently suffering a great deal… Sargent was very struck by the scene and immediately made a lot of notes”. For Sargent, it was harrowing, the most moving scene in his war experience. This was hardly surprising, given his memory of Rose-Marie’s work with similarly-afflicted men. As Corsano comments, these eye-bandaged, blinded soldiers must have visually recreated for him the blinded soldiers to whom Rose-Marie had dedicated the last years of her life [18].

The ultimate result was Sargent’s massive epic Gassed. Fully 20 feet (6m) wide, it presents an almost overwhelming panorama, dominated by a line of eight British soldiers, eyes bandaged as result of exposure to mustard gas, being guided by an orderly. They are moving from left to right along duckboards which provide a route over the muddy field. Each of them has his hand on the shoulder of the one in front of him, uncannily reminiscent of the line of blind peasants in Bruegel’s The Blind Leading the Blind (discussed in our article here). One of the blinded, fourth in the line from the left, turns away, apparently to retch. Another, third in line from the right, lifts his leg in an exaggerated way, unable to see his footing. They are making their way towards a field dressing station, whose taut tent ropes we can see at the right of the picture, near a pale rising moon, where another line of eight shuffle along, with two white coated medicos assisting.

In the foreground, more blinded soldiers sprawl exhausted, evidently awaiting their turn. In the background, just visible between the legs of the blinded at left, are more sprawled bodies and the tents of the encampment; and at right, some men in red and blue jumpers playing football, with the ball flying toward the goalkeeper, a bitter reminder of the normality of the outside world.

In the foreground, more blinded soldiers sprawl exhausted, evidently awaiting their turn. In the background, just visible between the legs of the blinded at left, are more sprawled bodies and the tents of the encampment; and at right, some men in red and blue jumpers playing football, with the ball flying toward the goalkeeper, a bitter reminder of the normality of the outside world.

The massive scale of the painting, and the viewer’s low point of view, combine to create an impression that the viewers have themselves entered the horrific scene. The painting is no rousing tribute to glorious sacrifice, but a stark reminder of the brutality and suffering the soldiers endured, a situation that Sargent had seen first-hand, but also – crucially -- one to which he had already been highly sensitised as a result of his knowledge of Rose-Marie’s years of nursing experience with the blind.

Rose-Marie in Sargent’s Triumph of Religion

When he finished Gassed, Sargent returned to a massive multi-panel project which he had been engaged on and off for decades. Back in 1890, he had accepted a commission for the mural decoration of the gallery of the special collections floor at the top of the Boston Library’s main staircase. Sargent had accepted the project as he, rather surprisingly, ranked public decoration as the highest task to which a painter could aspire, ranking it above figure composition and landscapes, with portraits at the bottom. He wanted to crown his artistic achievement with something grand, challenging and monumental [19]. Although not himself a deeply religious man, Sargent was very interested in religious imagery and iconography, and this was reflected in the grand theme that he devised ~ The Triumph of Religion [20].

The particular panels that Sargent returned to in 1919 were the murals Synagogue and Church. Both depict the consequences of Christ’s death. This, of course, had occurred on the original Good Friday, so it was almost inevitable that Sargent’s memories of the tragic events of Good Friday the previous year would be painfully present in his mind as he set to work.

The particular panels that Sargent returned to in 1919 were the murals Synagogue and Church. Both depict the consequences of Christ’s death. This, of course, had occurred on the original Good Friday, so it was almost inevitable that Sargent’s memories of the tragic events of Good Friday the previous year would be painfully present in his mind as he set to work.

The panel Church (Fig 15) shows an enthroned Madonna with a dead Christ slumped between her knees. Mary is portrayed simultaneously as the grieving mother of Christ but also an embodiment of the concept of the Church as the bride of Christ. She stares fixedly ahead. But there are some unusual aspects of this depiction. Her face, it has been argued, resembles Rose-Marie, and below the mantle over her head, her face is framed with a wimple -- the traditional headwear worn by the nurses at Reuilly hospital (see back, Fig 9). Extraordinarily, she also wears a grey army greatcoat, the “hand-me-down winter gear of a nurse in the Great War” [21].

In short, Sargent’s conception of Church has materially been affected by the War, and by Rose-Marie in particular. Corsano plausibly suggests that what Sargent had in mind was that the figure should be seen as not only the Church and the Pietà, but also as Rose-Marie herself, the martyr’s widow and military nurse. Seen this way, the painting thus becomes transformed into Sargent’s commemoration of his lost niece [22].

In short, Sargent’s conception of Church has materially been affected by the War, and by Rose-Marie in particular. Corsano plausibly suggests that what Sargent had in mind was that the figure should be seen as not only the Church and the Pietà, but also as Rose-Marie herself, the martyr’s widow and military nurse. Seen this way, the painting thus becomes transformed into Sargent’s commemoration of his lost niece [22].

This impression is confirmed by the presence of similar echoes of the War and blinded soldiers that appear in the Synagogue panel. Here, Sargent depicts a woman with bandaged eyes who has collapsed in the ruins of the Temple. This imagery was intended to reflect medieval Christian views as to the loss of the Synagogue’s authority, resulting from its failure to recognise the divinity of Christ. However, while the figure itself bears no resemblance at all to Rose-Marie, the parallels with her eye-bandaged patients, and to the circumstances of her death, are remarkable [23].

Aftermath

In 1922, after the Church of Saint Gervais had been rebuilt, a memorial for the victims of the Good Friday attack was dedicated in the memorial chapel, with a stained-glass window, a sculpture of a crowd of women and children being welcomed into heaven, and the names of all the known victims. In the same year, Rose-Marie’s body was solemnly transferred to Soissons, and placed in Robert’s soldier’s grave, just a few hundred yards from the spot where he had been killed eight years before. Their joint tombstone is there still. On a day before each Armistice Day, a procession of the local citizens goes there to hold a service, lay a wreath and sing the first verse and chorus of La Marseillaise [24].

Like countless other victims of war, Rose-Marie’s life was cut tragically and unjustly short. But in one sense, she still lives on. Thanks to Sargent’s watercolours, she still ponders by the side of the stream, still relaxes in the sunshine with her friends, still reclines languorously on grassy banks. Thanks to Sargent’s Gassed, the work Rose-Marie did with blind soldiers is honoured and remembered. And thanks to the Boston Library murals, Sargent perpetuates Rose-Marie’s work and the sacrifices that she and her husband made. In short, Rose-Marie’s story remains today as a potent reminder of the words of the Greek physician Hippocrates some 2,500 years ago. Life is short, art is long ■

© Philip McCouat 2019. First published June 2019.

This article may be cited as “Rose-Marie Ormond: John Singer Sargent’s muse and ‘the most charming girl that ever lived’” Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. If you enjoyed it, you may also enjoy our articles on Forgotten Women Artists.

Return to HOME

Like countless other victims of war, Rose-Marie’s life was cut tragically and unjustly short. But in one sense, she still lives on. Thanks to Sargent’s watercolours, she still ponders by the side of the stream, still relaxes in the sunshine with her friends, still reclines languorously on grassy banks. Thanks to Sargent’s Gassed, the work Rose-Marie did with blind soldiers is honoured and remembered. And thanks to the Boston Library murals, Sargent perpetuates Rose-Marie’s work and the sacrifices that she and her husband made. In short, Rose-Marie’s story remains today as a potent reminder of the words of the Greek physician Hippocrates some 2,500 years ago. Life is short, art is long ■

© Philip McCouat 2019. First published June 2019.

This article may be cited as “Rose-Marie Ormond: John Singer Sargent’s muse and ‘the most charming girl that ever lived’” Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. If you enjoyed it, you may also enjoy our articles on Forgotten Women Artists.

Return to HOME

End notes

[1] In the preparation of this article, I have drawn extensively on Karen Corsano and Daniel Williman’s excellent and comprehensive book John Singer Sargent and his Muse, an invaluable resource in this area. See also Cate McQuaid, Review of ‘John Singer Sargent and His Muse’, Boston Globe, 22 September 2014

[2] Cited in Corsano, at 53. Sargent considered portraiture a comparatively low form of the art of painting, “making homely people handsome to please their family”: op cit at 207.

[3] Corsano, op cit at 58.

[4] Corsano, op cit at 57-60.

[5] Corsano, op cit at 62.

[6] Corsano, op cit at 14.

[7] Corsano, op cit at 72. Rose-Marie also actively collaborated with Robert in his academic work.

[8] Quotations from Robert’s Journal are taken from Corsano, op cit at 102-124.

[9] Corsano, op cit at 136, 128

[10] Corsano, op cit at 140.

[11] Corsano, op cit at 163ff.

[12] Corsano, op cit at 159-60.

[13] Corsano, op cit at 166-68.

[14] Corsano, op cit at 168.

[15] William G Sharp, Washington, April 3rd 1918, Source Records of the Great War, Vol. VI, ed. Charles F. Horne, National Alumni 1923. Retrieved from https://www.firstworldwar.com/source/parisgun_sharp.htm June 2019.

[16] Corsano, op cit at 192.

[17] Corsano, op cit at 196.

[18] Corsano,op cit at 199.

[19] “Decoration” in this context does not mean mere prettification, but rather “beautiful, suitable and worthy of the place”: Corsano, op cit at 25, 207.

[20] For a detailed and perceptive analysis of the project, see also Sally M Promey, “Sargent’s Truncated Triumph: Art and Religion at the Boston Public Library, 1890-1925” The Art Bulletin, Vol 79, No 2 (June 1997) 217-250; and Corsano, op cit at 224ff.

[21] In an earlier preparatory sketch, Sargent even played with the idea of showing Christ as a wounded soldier in military garb, with bandages replacing the Crown of Thorns, but ultimately rejected it as too obvious: Corsano, op cit at 228.

[22] Corsano, op cit at 224ff. See also Promey, op cit.

[23] The painting attracted opposition by critics claiming variously that had a Christian bias, that it stereotyped Judaism and verged on anti-Semitism: see Promey, op cit at 232ff. The final part of the project was never finished, with the key panel Sermon on the Mount remaining undone on Sargent’s death in 1925.

[24] Corsano, op cit at 239.

© Philip McCouat 2019

This article may be cited as “Rose-Marie Ormond: John Singer Sargent’s muse and ‘the most charming girl that ever lived’” Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. If you enjoyed it, you may also enjoy our articles on Forgotten Women Artists.

Return to HOME

[2] Cited in Corsano, at 53. Sargent considered portraiture a comparatively low form of the art of painting, “making homely people handsome to please their family”: op cit at 207.

[3] Corsano, op cit at 58.

[4] Corsano, op cit at 57-60.

[5] Corsano, op cit at 62.

[6] Corsano, op cit at 14.

[7] Corsano, op cit at 72. Rose-Marie also actively collaborated with Robert in his academic work.

[8] Quotations from Robert’s Journal are taken from Corsano, op cit at 102-124.

[9] Corsano, op cit at 136, 128

[10] Corsano, op cit at 140.

[11] Corsano, op cit at 163ff.

[12] Corsano, op cit at 159-60.

[13] Corsano, op cit at 166-68.

[14] Corsano, op cit at 168.

[15] William G Sharp, Washington, April 3rd 1918, Source Records of the Great War, Vol. VI, ed. Charles F. Horne, National Alumni 1923. Retrieved from https://www.firstworldwar.com/source/parisgun_sharp.htm June 2019.

[16] Corsano, op cit at 192.

[17] Corsano, op cit at 196.

[18] Corsano,op cit at 199.

[19] “Decoration” in this context does not mean mere prettification, but rather “beautiful, suitable and worthy of the place”: Corsano, op cit at 25, 207.

[20] For a detailed and perceptive analysis of the project, see also Sally M Promey, “Sargent’s Truncated Triumph: Art and Religion at the Boston Public Library, 1890-1925” The Art Bulletin, Vol 79, No 2 (June 1997) 217-250; and Corsano, op cit at 224ff.

[21] In an earlier preparatory sketch, Sargent even played with the idea of showing Christ as a wounded soldier in military garb, with bandages replacing the Crown of Thorns, but ultimately rejected it as too obvious: Corsano, op cit at 228.

[22] Corsano, op cit at 224ff. See also Promey, op cit.

[23] The painting attracted opposition by critics claiming variously that had a Christian bias, that it stereotyped Judaism and verged on anti-Semitism: see Promey, op cit at 232ff. The final part of the project was never finished, with the key panel Sermon on the Mount remaining undone on Sargent’s death in 1925.

[24] Corsano, op cit at 239.

© Philip McCouat 2019

This article may be cited as “Rose-Marie Ormond: John Singer Sargent’s muse and ‘the most charming girl that ever lived’” Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. If you enjoyed it, you may also enjoy our articles on Forgotten Women Artists.

Return to HOME