The emergence of the winter landscape

Bruegel and his predecessors

Introduction

|

Pieter Bruegel’s familiar painting Hunters in the Snow [1] is now commonly regarded as the first fully realised winter landscape. But this painting did not appear until comparatively late, in 1565, and this raises the question of why such a seemingly obvious subject for painting took so long to evolve.

|

More on Bruegel

For more articles on Bruegel, see Icarus and the perils of flight /The Way to Calvary / Perception and Blindness ------------------------------------- |

Initially, this was probably due to European painters simply not recognising any natural scenery in their works, let alone climatic conditions. In early medieval times, the main purpose of art was to glorify God. In accordance with strict Christian teaching, the focus had therefore come to be on the spiritual world (it never rains in heaven), and earthly things tended to be denigrated or spurned. Added to this, worldly physical sensations were devalued. The 12th century monk St Anselm expressed this in an extreme form when he declared that things were harmful in proportion to the number of senses which they delighted; he would therefore rate it dangerous to sit in a garden where there were roses to satisfy the senses of sight and smell, and songs and stories to please the ears [2].

The combined effect of these factors was that medieval art came to oncentrate on the symbolic significance of the subject and its traditional mode of depiction, as distinct from what it actually looked like. Even when artists gradually started depicting conditions on earth as the background to their more realistic works, the treatment of the natural world was rudimentary. “Tame” nature was seen as purely a utilitarian adjunct to human development; and “wild” nature was still typically regarded as wasted, obstructive and unproductive, and therefore of little interest.

This was especially so in the case of winter-time – if people were primarily interested only in tame nature, this was the season when it was at its least welcoming. Furthermore, painting in general was significantly conditioned by Italian art which, because of that country’s climate, did not normally feature harsh, wintry conditions [3]. In addition, especially in agrarian societies, little outside work other than essential hunting was carried on outdoors during this time of year. People in these societies tended to stay inside during winter, sheltering from the cold; the bitter outdoors was simply not a place to linger or admire, let alone depict [4].

This general blindness was compounded by an actual deep-seated fear. This applied especially to mountains, which were commonly regarded as vertiginous sources of terror, pain and superstition [5]. It was not until 1336 that the Italian scholar and writer Petrarch was recorded as being the first man to climb a mountain for its own sake, and to enjoy the view from the top [6]. Even so, he shrank from enjoying it too much. After consulting his copy of St Augustine’s Confessions (which he happened to have handy), Petrarch became ashamed and angry with himself that he should “still be admiring earthly things”[7].

Against this apparently unpromising background, this article looks at how and why the necessary elements of a winter landscape gradually appeared in art, and how they finally came to fuse in Bruegel’s famous work [8].

The combined effect of these factors was that medieval art came to oncentrate on the symbolic significance of the subject and its traditional mode of depiction, as distinct from what it actually looked like. Even when artists gradually started depicting conditions on earth as the background to their more realistic works, the treatment of the natural world was rudimentary. “Tame” nature was seen as purely a utilitarian adjunct to human development; and “wild” nature was still typically regarded as wasted, obstructive and unproductive, and therefore of little interest.

This was especially so in the case of winter-time – if people were primarily interested only in tame nature, this was the season when it was at its least welcoming. Furthermore, painting in general was significantly conditioned by Italian art which, because of that country’s climate, did not normally feature harsh, wintry conditions [3]. In addition, especially in agrarian societies, little outside work other than essential hunting was carried on outdoors during this time of year. People in these societies tended to stay inside during winter, sheltering from the cold; the bitter outdoors was simply not a place to linger or admire, let alone depict [4].

This general blindness was compounded by an actual deep-seated fear. This applied especially to mountains, which were commonly regarded as vertiginous sources of terror, pain and superstition [5]. It was not until 1336 that the Italian scholar and writer Petrarch was recorded as being the first man to climb a mountain for its own sake, and to enjoy the view from the top [6]. Even so, he shrank from enjoying it too much. After consulting his copy of St Augustine’s Confessions (which he happened to have handy), Petrarch became ashamed and angry with himself that he should “still be admiring earthly things”[7].

Against this apparently unpromising background, this article looks at how and why the necessary elements of a winter landscape gradually appeared in art, and how they finally came to fuse in Bruegel’s famous work [8].

nature becomes more natural

The early 14th century painter Giotto [9] was one of the first Western painters of his time to depict realistic human gestures and expressions in recognisable, earthbound surroundings. However, Giotto often had difficulty in recreating the surroundings where they included the natural world. Paintings of this era commonly featured improbable, concrete-like rocks from which conventionally-realised trees and plants sometimes magically sprouted. The suggestion of Giotto’s follower Cennino Cennini that a good way of depicting mountains was to get some large rough stones and portray them from nature illustrated both the virtues and the limitations of this approach [10].

Significantly more realistic landscape effects emerged a few decades later, in the frescoes created by Ambrogio Lorenzetti at the Sala dei Nove in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena [11]. His work, the Effects of Good Government in the City and Countryside (1337-39), is significant for the amount of attention it gives to the scenery as well as to the human action. Unsurprisingly, especially given the title of the work, this scenery is thoroughly tamed and idealised, well tended with villas and farms surrounded by well-watered, rolling countryside. It is still very far from being an untamed wilderness..

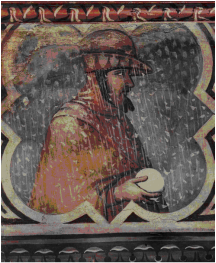

For our purposes, Lorenzetti’s work is also notable for a very rare and early depiction of snow. This appears in the main fresco’s border, which features various small medallions depicting the four seasons. While the medallions for the spring and summer months show the traditional labours for those seasons, the winter medallion departs from convention. Instead of the typical winter scene – an indoor setting, slaughter and curing of meats, woodcutting and so on – it depicts an outdoor leisure activity (Fig 4). A rugged-up gentleman is standing out in the falling snow, holding a large snowball in a rather pensive manner. Florian Heine suggests that “perhaps he does not know what to do with it”[12], but from the purposeful, narrowing of the man’s eyes he evidently has some tempting target in mind. It is the first modest intimation in art that people can actually have fun in the cold, as distinct from huddling inside for protection.

A little later, manuscripts of an influential Arab medical treatise started circulating in Europe, after being translated into Latin. The treatise was devoted to the beneficial and harmful properties of plants and animals, and the essential elements for well-being. Known as the Tacuinum Sanitatis (Maintenance of Health), it had had originally been written by an 11th century Christian physician based in Baghdad, Abu I-Hasam (called Ibn Butlan) [13].

A little later, manuscripts of an influential Arab medical treatise started circulating in Europe, after being translated into Latin. The treatise was devoted to the beneficial and harmful properties of plants and animals, and the essential elements for well-being. Known as the Tacuinum Sanitatis (Maintenance of Health), it had had originally been written by an 11th century Christian physician based in Baghdad, Abu I-Hasam (called Ibn Butlan) [13].

|

One crucial aspect of this work was that it came to include many illustrations by contemporary artists from Lombardy in the north of Italy. Significantly, the objects mentioned in the text, such as plants or animals, were illustrated not simply as objects themselves without context, but as part of their natural setting, so that readers could experience them as they did in everyday life [14].

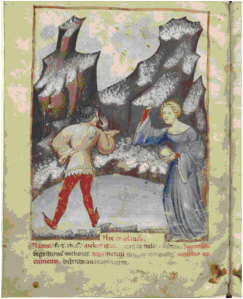

Some also showed not a specific plant or fruit, but a specific condition of nature, such as one of the seasons, or phenomena such as snowy mountains - even a snowball fight - rain, or snowfall (fig 5). |

This was a new approach. The Tacuinum thus exhibited two of the elements that would be relevant for the emergence of the type of winter landscape Bruegel would eventually depict – the increased importance of a natural, sometimes even untamed background to man’s activities, and the crucial, if rather unconvincing, appearance of snow-covered mountains.

Italian lords and ladies frolic with snowballs

An illustrated version of the Tacuinum happened to be owned by the Bishop of Trento who, early in the fifteenth century, commissioned Master Wenceslas of Bohemia to execute a series of frescoes to decorate the Eagle Tower of the Bishop’s Palace [15].

These Trento frescoes depicted the cycle of the months, and have been described as the first monumental depiction of the calendar months, as distinct from book illustrations [16]. The fresco for the month of January, depicting a snow ball fight, is also possibly the first full-scale painting showing a true winter scene.

The large fresco (Fig 6) shows a precisely-executed snow covered landscape outside the Bishop’s Palace itself (which remains miraculously snow-free) featuring the “Bishop and his noble companions …enjoying [a] snowball fight"[17], with the women giving as good as they got (and one thoughtfully fully-armed with a lap full of snowy missiles). The picture plane is flattened and the rudimentary perspective means that all human figures are unnaturally large compared to their surroundings [18]. In the background are hunters with dogs, and in the far distance, rather unconvincing, but definitely snowy, mountains. The frescoes are far more complex and ambitious than the vignettes of scenery in the Tacuinum, adopt a much wider perspective, and firmly establish snowy scenes are worthwhile subjects for art, not just illustration – all essential elements in the development of the genre.

These Trento frescoes depicted the cycle of the months, and have been described as the first monumental depiction of the calendar months, as distinct from book illustrations [16]. The fresco for the month of January, depicting a snow ball fight, is also possibly the first full-scale painting showing a true winter scene.

The large fresco (Fig 6) shows a precisely-executed snow covered landscape outside the Bishop’s Palace itself (which remains miraculously snow-free) featuring the “Bishop and his noble companions …enjoying [a] snowball fight"[17], with the women giving as good as they got (and one thoughtfully fully-armed with a lap full of snowy missiles). The picture plane is flattened and the rudimentary perspective means that all human figures are unnaturally large compared to their surroundings [18]. In the background are hunters with dogs, and in the far distance, rather unconvincing, but definitely snowy, mountains. The frescoes are far more complex and ambitious than the vignettes of scenery in the Tacuinum, adopt a much wider perspective, and firmly establish snowy scenes are worthwhile subjects for art, not just illustration – all essential elements in the development of the genre.

keeping warm in burgundy

Around the same time as the Trento frescoes, the Limbourg Brothers [19] began work on the Tres Riches Heures – a commissioned work for the fabulously wealthy, high-ranking aristocrat Burgundian Duc du Berry.

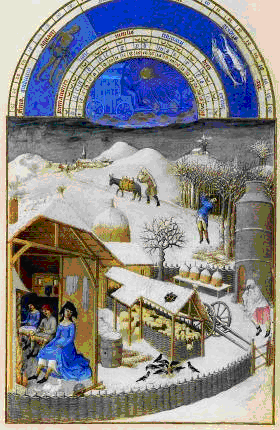

Books of Hours had started appearing in the 13th century. Essentially, they were prayer books – a compendium of psalms, bible verses, hymns and prayers for private devotional use. Gradually, they came to be illustrated, and a tradition grew of including lavishly illustrated calendars. The example in the Tres Riches Heures of most interest for our purposes is the one depicting an obviously icy February [20]. With a level of detail which is extraordinary for its diminutive size [21], it depicts a small farm in a snowy landscape, under a pewter-grey sky [22]. In the foreground is a wooden house, whose entire front has been cut away by the artists so that the interior is revealed like a proscenium stage.

Books of Hours had started appearing in the 13th century. Essentially, they were prayer books – a compendium of psalms, bible verses, hymns and prayers for private devotional use. Gradually, they came to be illustrated, and a tradition grew of including lavishly illustrated calendars. The example in the Tres Riches Heures of most interest for our purposes is the one depicting an obviously icy February [20]. With a level of detail which is extraordinary for its diminutive size [21], it depicts a small farm in a snowy landscape, under a pewter-grey sky [22]. In the foreground is a wooden house, whose entire front has been cut away by the artists so that the interior is revealed like a proscenium stage.

Inside, there sit a well-dressed lady in blue and a young man and woman. All are warming themselves at the fire, the lady decorously lifting her skirts up to her calves, revealing a few inches of prim underwear. The young couple are more direct – both have hitched their leggings as far as possible, unconcernedly revealing their own total lack of underclothes [23]. In the background, the presence of a bed (not just straw) indicates some pretension to wealth, as does the smoking chimney and the dovecote in the outside yard [24].

In the snowy outdoors, a man (presumably the lady’s equally well-dressed husband) is swinging a languid axe at the leafless trees. Another man, more coarsely dressed, with an improvised head protection, his expelled breath just visible as it freezes before him, is driving a mule/donkey laden with wood along the trail to the village round the hillside. In the farmyard are various aspects of the agrarian economy – sheep huddling together in the pen (generators of meat, wool and milk), magpies crowding around seed on the ground, beehives (providing honey/sweetener and wax for candles) and snow covered haystacks.

Though not shirking depicting the effects of the cold – observe the old woman at lower right, her face muffled, hurrying to get out of the chill – this is a rather idealised view, created by privileged artists for the privileged few. But, crucially, it is a work whose detailed treatment clearly indicates that the artists had closely observed their surroundings, not just imagined them. The environment’s central role also meant that, with a significant amount of landscape to organise, the artists faced greater compositional challenges. These challenges had been met rudimentarily in the Trento fresco, which consisted essentially of three rectangles of unconnected action, but the Limbourgs’ February shows considerably more sophistication. The scene is unified by a softly curving s-line that begins with the line of the fence in the foreground, curls round to the trail leading to the village, then round the foothill to the village itself [25].

The snow, instead of looking vaguely like dirty cotton wool strewn on the ground (as in the Trento fresco) actually looks like it has fallen from the sky, and varies in subtle tones of blue, grey and yellow. The artists have also integrated the snow into the actual composition of the work, using it to form a sharp tonal contrast with the birds, highlighting the structure of the steeple in the distance, and enabling the bare branches of the trees to be individually delineated [26]. The perspective is coherent without being realistic [27], with figures still hieratically inflated in size, though not to the extent shown in the Trento fresco.

As we shall see, many of these features will reappear in Bruegel’s work – the emphasis on daily agrarian activities, the variations of toning in the leaden sky and white snow, the contrasts provided by the dark birds, the atmospheric effect of the misty town in the background. The Limbourgs, in their turn, may actually have been directly influenced by some of the works discussed previously. It seems that they (or at least Paul Limbourg) had visited Italy, and specifically the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, so it is likely that they were at least aware of Lorenzetti’s work there, with its impressive new emphasis on the importance of the natural surroundings [28]. Pacht speculates that they may also have been influenced by the illustrations in the Tacuinum Sanitatis – the motif of the woman raising her skirts to fully warm herself had already appeared in that work [29].

In the snowy outdoors, a man (presumably the lady’s equally well-dressed husband) is swinging a languid axe at the leafless trees. Another man, more coarsely dressed, with an improvised head protection, his expelled breath just visible as it freezes before him, is driving a mule/donkey laden with wood along the trail to the village round the hillside. In the farmyard are various aspects of the agrarian economy – sheep huddling together in the pen (generators of meat, wool and milk), magpies crowding around seed on the ground, beehives (providing honey/sweetener and wax for candles) and snow covered haystacks.

Though not shirking depicting the effects of the cold – observe the old woman at lower right, her face muffled, hurrying to get out of the chill – this is a rather idealised view, created by privileged artists for the privileged few. But, crucially, it is a work whose detailed treatment clearly indicates that the artists had closely observed their surroundings, not just imagined them. The environment’s central role also meant that, with a significant amount of landscape to organise, the artists faced greater compositional challenges. These challenges had been met rudimentarily in the Trento fresco, which consisted essentially of three rectangles of unconnected action, but the Limbourgs’ February shows considerably more sophistication. The scene is unified by a softly curving s-line that begins with the line of the fence in the foreground, curls round to the trail leading to the village, then round the foothill to the village itself [25].

The snow, instead of looking vaguely like dirty cotton wool strewn on the ground (as in the Trento fresco) actually looks like it has fallen from the sky, and varies in subtle tones of blue, grey and yellow. The artists have also integrated the snow into the actual composition of the work, using it to form a sharp tonal contrast with the birds, highlighting the structure of the steeple in the distance, and enabling the bare branches of the trees to be individually delineated [26]. The perspective is coherent without being realistic [27], with figures still hieratically inflated in size, though not to the extent shown in the Trento fresco.

As we shall see, many of these features will reappear in Bruegel’s work – the emphasis on daily agrarian activities, the variations of toning in the leaden sky and white snow, the contrasts provided by the dark birds, the atmospheric effect of the misty town in the background. The Limbourgs, in their turn, may actually have been directly influenced by some of the works discussed previously. It seems that they (or at least Paul Limbourg) had visited Italy, and specifically the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, so it is likely that they were at least aware of Lorenzetti’s work there, with its impressive new emphasis on the importance of the natural surroundings [28]. Pacht speculates that they may also have been influenced by the illustrations in the Tacuinum Sanitatis – the motif of the woman raising her skirts to fully warm herself had already appeared in that work [29].

The scene becomes a panorama

By the next century, landscapes had came to assume greater importance in mainstream art. The Flemish painter Joachim Patinir (1480-1524) had become a pioneer of landscape as an independent genre, bringing it to a level of relative independence [30]. His pictures typically created impressions of vast spaces – wide-angled panoramas, viewed from a high point, often featuring distant mountain ranges, and a lowered horizon which allowed a more expansive sky. As we shall see, these were all features that would feature in Bruegel’s work.

However, his nominal subjects were still restricted to stories from the Bible, or the lives of saints [31] and, as with Hieronymous Bosch before him, the scenes depicted were largely imagined, almost dream-like, full of detail, but not having the realistic edge that comes from a Dürer-like close observation of “real” life, as evidenced in that painter's watercolours, such as View of Arco (1495). Paradoxically, too, Patinir’s inconsistent representation of perspective made some of his works appear curiously flattened [32]. Meanwhile, in a further development, the German Albrecht Altdorfer was creating a panorama of an actual location, seemingly devoid of humans altogether, in his View of the Danube Valley near Regensburg (ca 1520).

hunters in the snow

So, finally, a few decades later, we come to Hunters in the Snow.

Hunters is one of the surviving panels of a series called The Months [33], originally commissioned for the Antwerp mansion of Niclaes Jonghelinck. The series, painted over the period 1564/65, depicts the cycle of rural life as the seasons changed.

Hunters itself represents mid-winter (probably December/January). The actual winter of 1564/65 was particularly harsh, and some have suggested that it was this that inspired Bruegel to paint Hunters as an outdoor snow scene [34]. Supporters of this view argue that even the Months paintings set in spring and autumn show them as being cooler than they are in modern times [35]. However, this may be a case of seeing what you want to see – others have described Bruegel’s June as a “radiant expression of high spring” [36] and August as “the flat glowing scenery [that] is pure midsummer” [37]. It also needs to be remembered that although Hunters is evidently based on close observation, it cannot be regarded as a accurate depiction of a particular time or place – if it were, we would have to explain how a huge mountain range has somehow migrated into the Low Countries.

Hunters is one of the surviving panels of a series called The Months [33], originally commissioned for the Antwerp mansion of Niclaes Jonghelinck. The series, painted over the period 1564/65, depicts the cycle of rural life as the seasons changed.

Hunters itself represents mid-winter (probably December/January). The actual winter of 1564/65 was particularly harsh, and some have suggested that it was this that inspired Bruegel to paint Hunters as an outdoor snow scene [34]. Supporters of this view argue that even the Months paintings set in spring and autumn show them as being cooler than they are in modern times [35]. However, this may be a case of seeing what you want to see – others have described Bruegel’s June as a “radiant expression of high spring” [36] and August as “the flat glowing scenery [that] is pure midsummer” [37]. It also needs to be remembered that although Hunters is evidently based on close observation, it cannot be regarded as a accurate depiction of a particular time or place – if it were, we would have to explain how a huge mountain range has somehow migrated into the Low Countries.

The painting centres around a snow-bound village. A small group of men are returning wearily from the hunt, trudging through the snow, a fox (or rabbit?) as their only reward, with their motley collection of dogs following behind. To their left, at the Inn, villagers are singeing a pig’s bristles at a fire. Ahead of the hunters (and the viewer) is a vast panorama. Down the steep hill, bulkily-clad villagers are engaging in various activities, skating on the frozen ponds, playing a form of hockey, curling and spinning tops. In the far distance on the right are precipitous mountains, reminiscent of the alpine scenes Bruegel had seen on an earlier trip to Italy [38]. In the distance left, we can just make out a town. There is an almost palpable sense of cold, reinforced by the hunched postures of the figures in the foreground, the evident deepness of the snow, the ice-green of the frozen ponds mirrored in the leaden sky, the bareness of the trees.

Unlike Patinir’s works, the scene is entirely secular. Apart from incidental church steeples, there are no overt religious references in the painting. Again in contrast to Patinir, there is no artificial or dream-like quality – it is rooted in reality, simply depicting anonymous, ordinary people doing ordinary things in a completely naturalistic setting. The scene pictured here is timeless: it could have taken place, with only minor variations, in any one of a number of centuries. Perhaps these factors contribute to the experience that some viewers have of actually “being there”, almost as if they were sitting with the artist on a branch of an unseen tree, watching the scene unfold before them. This is underlined by the extraordinary level of detail – the numerous detailed vignettes of everyday life, the informal touches of the birds sitting and flitting in the trees (some almost level with the viewer’s vantage point), the contrast of their dark shapes against the sky and snow, the dog nearest the tree who turns to look at the viewer, the careful lettering on the sign identifying the Inn of the Stag.

As with the Tres Riches Heures, the sheer amount of landscape raises compositional challenges for the artist. Here, Bruegel unifies the scene by providing a strong diagonal running from the roof of the inn to the lower right corner, defining the snowy rise that the hunters are traversing. Another diagonal runs from the mountains back towards the inn. But dominating the composition is the diagonal line described by the slim, dark-trunked trees in the foreground, defining the direction in which the hunters are moving. This line is continued in the spindly trees along the side of the frozen lake, and leads the eye from the hunters down the hill to the villagers on the valley floor, and then all the way to the precipitous mountains in the distance. The composition gives a strong feeling of depth that, along with the sense of presence discussed already, masks some minor discrepancies in perspective, such as the relative sizes of some of the villagers.

Unlike Patinir’s works, the scene is entirely secular. Apart from incidental church steeples, there are no overt religious references in the painting. Again in contrast to Patinir, there is no artificial or dream-like quality – it is rooted in reality, simply depicting anonymous, ordinary people doing ordinary things in a completely naturalistic setting. The scene pictured here is timeless: it could have taken place, with only minor variations, in any one of a number of centuries. Perhaps these factors contribute to the experience that some viewers have of actually “being there”, almost as if they were sitting with the artist on a branch of an unseen tree, watching the scene unfold before them. This is underlined by the extraordinary level of detail – the numerous detailed vignettes of everyday life, the informal touches of the birds sitting and flitting in the trees (some almost level with the viewer’s vantage point), the contrast of their dark shapes against the sky and snow, the dog nearest the tree who turns to look at the viewer, the careful lettering on the sign identifying the Inn of the Stag.

As with the Tres Riches Heures, the sheer amount of landscape raises compositional challenges for the artist. Here, Bruegel unifies the scene by providing a strong diagonal running from the roof of the inn to the lower right corner, defining the snowy rise that the hunters are traversing. Another diagonal runs from the mountains back towards the inn. But dominating the composition is the diagonal line described by the slim, dark-trunked trees in the foreground, defining the direction in which the hunters are moving. This line is continued in the spindly trees along the side of the frozen lake, and leads the eye from the hunters down the hill to the villagers on the valley floor, and then all the way to the precipitous mountains in the distance. The composition gives a strong feeling of depth that, along with the sense of presence discussed already, masks some minor discrepancies in perspective, such as the relative sizes of some of the villagers.

Conclusion

Tracing historical trends in art is an exercise in hindsight, and it is a mistake to assume that there is some inevitability in the way that events unfold, or to conclude that changes necessarily represent improvements. For similar reasons, what happened in the past is not necessarily any guide at all to what might happen in the future. Nevertheless, knowing a particular end-result, it is legitimate to attempt to go back and identify some of the critical stages in the way in which the elements of that end result came about, whether that be by design, inspiration or chance.

In the case of winter landscapes, we have seen the emergence over time of a series of factors: an elevated perspective, snow, mountains, incidental human interaction with the environment, a realistic sense of place, a palpable feeling of cold, and an appreciation of the scene for its own sake, without outward religious, utilitarian or moral overtones. These developments reflect some wider important changes in approach that had taken place over time – changes in views of the relative importance of the secular and sacred worlds, of the way in which humans relate to their natural environment, and of the way in which that environment should be portrayed. The fact that these are all quite fundamental questions, ones still being dealt with by people today, serves to underline the important role that art can sometimes play as an (often-distorted) mirror of changing social and intellectual attitudes.□

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

How to cite this article

This article may be cited as:

Philip McCouat, "The emergence of the winter landscape: Bruegel and his predecessors", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

You may also enjoy….

If you enjoyed this article, you may also be interested in:

On the trail of the Last Supper

Floating Worlds of Paris and Edo

We welcome your comments on this article.

Back to HOME

In the case of winter landscapes, we have seen the emergence over time of a series of factors: an elevated perspective, snow, mountains, incidental human interaction with the environment, a realistic sense of place, a palpable feeling of cold, and an appreciation of the scene for its own sake, without outward religious, utilitarian or moral overtones. These developments reflect some wider important changes in approach that had taken place over time – changes in views of the relative importance of the secular and sacred worlds, of the way in which humans relate to their natural environment, and of the way in which that environment should be portrayed. The fact that these are all quite fundamental questions, ones still being dealt with by people today, serves to underline the important role that art can sometimes play as an (often-distorted) mirror of changing social and intellectual attitudes.□

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

How to cite this article

This article may be cited as:

Philip McCouat, "The emergence of the winter landscape: Bruegel and his predecessors", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

You may also enjoy….

If you enjoyed this article, you may also be interested in:

On the trail of the Last Supper

Floating Worlds of Paris and Edo

We welcome your comments on this article.

Back to HOME

End notes

[1] Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca 1525-1569). He changed the spelling from “Brueghel” in 1559. The original painting itself was not titled.

[2] Kenneth Clark, Landscape into Art, Beacon Press, Boston, 1961, at 2. It was not always so, especially in book illustrations. See, for example, the informal naturalistic sketches that illustrated the Utrecht Psalter (ca 830) and the Julius Work Calendar (ca 1100): see generally Robert Lacey and Danny Danziger, The Year 1000, Abacus, London 1999.

[3] Peter J Robertson, “Ice and Snow in Paintings of Little Ice Age Winters”, 2005 Weather 60 (2) 37, at 38.

[4] Interestingly, there were also very few early depictions of night-time: Florian Heine, The First Time. Bucher, Munich, 2007 at 22.

[5] Fergus Fleming, Killing Dragons: The Conquest of the Alps, Granta Books, London 2000 at 4-5.

[6] Clark, op cit at 7. The mountain was Mt Ventoux in the Provence Alps.

[7] This generalised fear proved to be long-lasting. Even in Bruegel’s time, and beyond, actual mountains were far from being generally regarded as picturesque features.

[8] This article, necessarily selective, is not intended as a general history of early landscape art. Nor does it deal with the long tradition of landscapes in oriental art.

[9] Giotto di Bondone (ca 1266-1337).

[10] Clark, op cit at 11.

[11] Lorenzetti died only a few years later (ca 1348), probably as a result of the Black Death (see Surviving the Black Death).

[12] Heine, op cit at 33.

[13] His work, in turn, was apparently based on classical sources dating back to the 1st century BCE.

[14] Otto Pacht, "Early Italian nature studies and the early calendar landscape”, Journal of the Warburg and Cortauld Institutes, Volume 13. 1950, 35-47, at 35.

[15] Pacht, op cit at 41.

[16] Heine, op cit at 33.

[17] Heine, op cit at 34.

[18] “True” perspective would not emerge for another 20 years.

[19] Paul, Herman and Johan Limbourg, from Nimwegen in present day Flanders. All three brothers died in the same year, 1416. Like Lorenzetti before them, they were possibly victims of an outbreak of the plague. They had not completed the Book of Hours at the time of their death, but other artists finished the project.

[20] Interestingly, during the period 1408-16 when the paintings were done, there were at least two winters that were extreme: Hagen, op cit at 20.

[21] Approx 8.9in x 5.4in or 22.5 cm x 13.6 cm.

[22] See generally Lillian Schacherl’s excellent description in Très Riches Heures: Behind the Gothic Masterpiece, Prestel-Verlag, Munich and New York, 1997.

[23] Not surprisingly, this was a sign of lower status. Lower classes often urinated in public “though they have no hose, they do not fear the gaze of passers-by”: cited in Hagen, op cit at 25. Reportedly, the couple’s exposed genitalia were brushed out in reproductions of the miniature that appeared in Life magazine in 1948.

[24] These status symbols suggest that the house is that of a factor/bailiff on a landholder’s property: Hagen, op cit at 25.

[25] Schacherl, op cit at 48. A very similar motif, albeit in a non-winter context, appears in Robert Campin's Dijon Nativity (c1425):.

[26] Schacherl, op cit at 46.

[27] David Piper, The Illustrated History of Art, Bounty, London 2005, at 89.

[28] Pacht, op cit at 41.

[29] Pacht 38; see also P Toesca, La Pittura e la Miniatura nells Lombardia, Ulrico Hoepli, Milano 1912, accessed through www.openlibrary.org, p 419, 344 (fig 271).

[30] Wolfgang Stechow, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Harry N Abrams Inc, New York, 1990, at 17.

[31] For example, Landscape with the Martyrdom of St Catherine 1510-15); and The Penitence of St Jerome (ca 1518).

[32] As to whether this was deliberate or was a technical fault, see Verena Voigt, “Joachim Patinir (ca 1485-1524) and the beginnings of landscape painting in the low countries”, Canadian Journal of Netherlandic Studies, Issue XIV 1993, p 19.

[33] Only five survive. Originally, there were possibly 12 but more likely six, covering the 12 months of the year.

[34] Reportedly, it was one of the few occasions when a “frost fair” was conducted on the frozen River Thames in London. The series of bitterly cold winters experienced during the 1550s in northern Europe is sometimes considered to be the start of the so-called “Little Ice Age”, which lasted into the nineteenth century.

[35] These views are summarised in John E Thomas, John Constable’s Skies, A Fusion of Art and Science, University of Birmingham Press, Edgbaston, 1999, at 160-1. See also Robertson, op cit.

[36] Timothy Foote, The World of Bruegel, Time-Life Books, Inc, 1971, at 176.

[37] Foote, op cit at 178.

[38] In 1604 Carel van Mander said that that Bruegel did so many views from nature, that it was said of him when he travelled through the Alps that he had “swallowed all the mountains and the rocks of the Alps and spat them out again, after his return, onto his canvases and panels”: Ian Chilvers, Oxford Concise Dictionary of Art and Artists (3 edn), Oxford, 2003, at 89.

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The emergence of the winter landscape: Bruegel and his predecessors", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article.

Back to HOME

[2] Kenneth Clark, Landscape into Art, Beacon Press, Boston, 1961, at 2. It was not always so, especially in book illustrations. See, for example, the informal naturalistic sketches that illustrated the Utrecht Psalter (ca 830) and the Julius Work Calendar (ca 1100): see generally Robert Lacey and Danny Danziger, The Year 1000, Abacus, London 1999.

[3] Peter J Robertson, “Ice and Snow in Paintings of Little Ice Age Winters”, 2005 Weather 60 (2) 37, at 38.

[4] Interestingly, there were also very few early depictions of night-time: Florian Heine, The First Time. Bucher, Munich, 2007 at 22.

[5] Fergus Fleming, Killing Dragons: The Conquest of the Alps, Granta Books, London 2000 at 4-5.

[6] Clark, op cit at 7. The mountain was Mt Ventoux in the Provence Alps.

[7] This generalised fear proved to be long-lasting. Even in Bruegel’s time, and beyond, actual mountains were far from being generally regarded as picturesque features.

[8] This article, necessarily selective, is not intended as a general history of early landscape art. Nor does it deal with the long tradition of landscapes in oriental art.

[9] Giotto di Bondone (ca 1266-1337).

[10] Clark, op cit at 11.

[11] Lorenzetti died only a few years later (ca 1348), probably as a result of the Black Death (see Surviving the Black Death).

[12] Heine, op cit at 33.

[13] His work, in turn, was apparently based on classical sources dating back to the 1st century BCE.

[14] Otto Pacht, "Early Italian nature studies and the early calendar landscape”, Journal of the Warburg and Cortauld Institutes, Volume 13. 1950, 35-47, at 35.

[15] Pacht, op cit at 41.

[16] Heine, op cit at 33.

[17] Heine, op cit at 34.

[18] “True” perspective would not emerge for another 20 years.

[19] Paul, Herman and Johan Limbourg, from Nimwegen in present day Flanders. All three brothers died in the same year, 1416. Like Lorenzetti before them, they were possibly victims of an outbreak of the plague. They had not completed the Book of Hours at the time of their death, but other artists finished the project.

[20] Interestingly, during the period 1408-16 when the paintings were done, there were at least two winters that were extreme: Hagen, op cit at 20.

[21] Approx 8.9in x 5.4in or 22.5 cm x 13.6 cm.

[22] See generally Lillian Schacherl’s excellent description in Très Riches Heures: Behind the Gothic Masterpiece, Prestel-Verlag, Munich and New York, 1997.

[23] Not surprisingly, this was a sign of lower status. Lower classes often urinated in public “though they have no hose, they do not fear the gaze of passers-by”: cited in Hagen, op cit at 25. Reportedly, the couple’s exposed genitalia were brushed out in reproductions of the miniature that appeared in Life magazine in 1948.

[24] These status symbols suggest that the house is that of a factor/bailiff on a landholder’s property: Hagen, op cit at 25.

[25] Schacherl, op cit at 48. A very similar motif, albeit in a non-winter context, appears in Robert Campin's Dijon Nativity (c1425):.

[26] Schacherl, op cit at 46.

[27] David Piper, The Illustrated History of Art, Bounty, London 2005, at 89.

[28] Pacht, op cit at 41.

[29] Pacht 38; see also P Toesca, La Pittura e la Miniatura nells Lombardia, Ulrico Hoepli, Milano 1912, accessed through www.openlibrary.org, p 419, 344 (fig 271).

[30] Wolfgang Stechow, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Harry N Abrams Inc, New York, 1990, at 17.

[31] For example, Landscape with the Martyrdom of St Catherine 1510-15); and The Penitence of St Jerome (ca 1518).

[32] As to whether this was deliberate or was a technical fault, see Verena Voigt, “Joachim Patinir (ca 1485-1524) and the beginnings of landscape painting in the low countries”, Canadian Journal of Netherlandic Studies, Issue XIV 1993, p 19.

[33] Only five survive. Originally, there were possibly 12 but more likely six, covering the 12 months of the year.

[34] Reportedly, it was one of the few occasions when a “frost fair” was conducted on the frozen River Thames in London. The series of bitterly cold winters experienced during the 1550s in northern Europe is sometimes considered to be the start of the so-called “Little Ice Age”, which lasted into the nineteenth century.

[35] These views are summarised in John E Thomas, John Constable’s Skies, A Fusion of Art and Science, University of Birmingham Press, Edgbaston, 1999, at 160-1. See also Robertson, op cit.

[36] Timothy Foote, The World of Bruegel, Time-Life Books, Inc, 1971, at 176.

[37] Foote, op cit at 178.

[38] In 1604 Carel van Mander said that that Bruegel did so many views from nature, that it was said of him when he travelled through the Alps that he had “swallowed all the mountains and the rocks of the Alps and spat them out again, after his return, onto his canvases and panels”: Ian Chilvers, Oxford Concise Dictionary of Art and Artists (3 edn), Oxford, 2003, at 89.

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The emergence of the winter landscape: Bruegel and his predecessors", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article.

Back to HOME