FROM THE ROKEBY VENUS TO FASCISM

Pt 1: Why did suffragettes attack artworks?

The attack on the rokeby Venus

Just on 100 years ago, a small soberly-dressed woman carrying a sketch book entered the National Gallery in London and physically attacked one of the most famous nude paintings in the world (Fig 1).

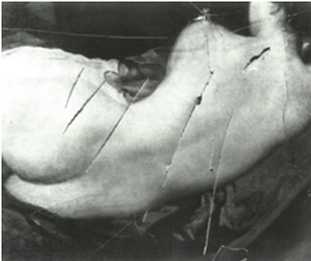

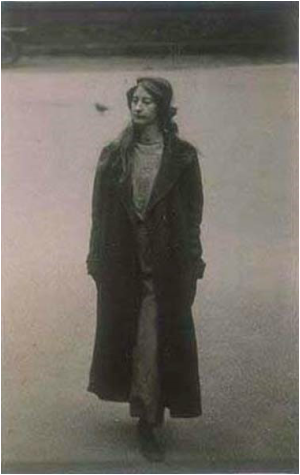

It was just after 10 o’clock on the morning of 10 March 1914 [1]. The painting, Velásquez’s so-called “Rokeby Venus” [2], was standing on an easel in Room 17, temptingly accessible. The woman stepped forward, took a narrow meat chopper which had been concealed up her sleeve and began swinging, getting in what she later described as several “lovely shots”, smashing the protective glass and making numerous large slashes in the painted canvas (Fig 3). The room attendant’s initial belief that the breaking glass was coming from a skylight gave the woman precious time to carry out the attack, and the delay in stopping her was compounded by the attendant slipping on the recently-polished floor when running to intervene. However, the attacker was eventually restrained, and arrested. On the next day, now identified as the well-known militant suffragette Mary Richardson (Fig 2), she was convicted on charges of malicious damage, and sentenced to the maximum penalty of six months imprisonment.

After Richardson’s arrest, she explained her actions on the basis that, “I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government destroying Mrs Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history. Justice is an element of beauty as much as colour and outline on canvas” [3]. “Mrs Pankhurst” was Emmeline Pankhurst, the campaigner for women’s voting rights and leader of the militant Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), who had been arrested in extraordinarily violent circumstances the day before. Richardson’s view was that if people were outraged about her own attack on the painting, which was a mere representation of physical beauty, they should be equally or more outraged over the government’s treatment of Pankhurst, a real embodiment of moral beauty.

Richardson insisted that as a student of art herself it had been difficult for her to damage such a beautiful work, but that her hand had been forced by the government’s indifference to the suffragist cause [4]. She also added “You can get another picture, but you cannot get a life, as they are killing Mrs Pankhurst" [5]. In her autobiography [6], Richardson also said that the high financial value of the painting made it a suitable surrogate for the high value of Mrs Pankhurst. A less elevated consideration emerged in an interview Richardson gave some decades later: “I didn’t like the way men visitors to the gallery gaped at it all day” [7].

Richardson insisted that as a student of art herself it had been difficult for her to damage such a beautiful work, but that her hand had been forced by the government’s indifference to the suffragist cause [4]. She also added “You can get another picture, but you cannot get a life, as they are killing Mrs Pankhurst" [5]. In her autobiography [6], Richardson also said that the high financial value of the painting made it a suitable surrogate for the high value of Mrs Pankhurst. A less elevated consideration emerged in an interview Richardson gave some decades later: “I didn’t like the way men visitors to the gallery gaped at it all day” [7].

“A body for Don Juanesque fantasies”

In many ways the Rokeby Venus was an ideal target for suffragette attack. As the commentators Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen say, it was originally painted to display “a body for Don Juanesque fantasies” in a country (Spain) in which extreme machismo was the hallmark and women were regarded as “inferior, voiceless and … easy prey”. They add that “few other paintings celebrate, so aesthetically and alluringly, the reduction of Woman to a physical body, to the object of male desire. Venus's face, which might reveal something of her individuality and mind, is blurred in the mirror, while her curving pelvis is placed in the centre of the composition. The dark sheet sets off Venus's skin to particular advantage and is almost like a dish on which the beautiful goddess is presented” [8].

Although being regarded as the first known painting of a nude by a Spanish artist [8A] – the next one would not be until Goya's Naked Maja more than a century later – the Venus escaped censure from the Inquisition only by the fact that it was nominally of a mythological subject, and had been painted under the personal protection of the licentious Spanish King Philip IV. All in all, then, the idea of attacking it could well seem attractive to a fighter for women's rights. As an added bonus, attacking the painting would enable Richardson to come as near as possible to blood-shedding without actually infringing the suffragettes’ policy of not endangering human life [9].

Yet, from a public relations viewpoint, Richardson’s choice of target was actually quite problematic. The painting had only recently been acquired by the National Gallery after its previous owner, John Morritt MP of Rokeby Hall in Yorkshire (from which the painting gained its recent popular name) had put it up for sale. In private correspondence, Morritt had described the painting as his “fine picture of Venus’s backside”, and he had hung it prominently over his fireplace, which raised “the said backside to a considerable height” [10].

The £45,000 purchase price – a very substantial amount at the time – was raised by a widely-supported public subscription, including a crucial contribution by King Edward VII himself. The public therefore felt that it had a considerable financial, emotional and even patriotic stake in the painting. Its destruction was therefore hardly likely to attract popular support, particularly as the slashes were so disturbingly realistic in their impact.

At a more general level, people would be far more likely to form a strong attachment to a painting that they would with other suffragist targets of destruction, such as haystacks, sports pavilions, windows or letter boxes. As Rowena Fowler has pointed out, “it was not necessary to be an art lover or connoisseur to be disturbed by the threat to a valuable but vulnerable national possession; it was genuinely upsetting to see beautiful things spoiled and to find ‘great’ and ‘timeless’ works of art forced into proximity with the messiness of contemporary political conflict” [11]. The negative impact was increased by the brazenness of the attack and the fact that Richardson appeared to bask in her own publicity, taking pride in her action, rather than exhibiting what was felt to be a sufficient level of genuine remorse.

More prosaically, those who had contributed to the purchase of the painting would have been annoyed by reports that the attack had substantially reduced its value. The Keeper of the National Gallery had, for example, estimated that the value of the Venus had been reduced by ₤10-15,000 [12]. The WSPU counter-argued that “the Rokeby Venus has, because of Miss Richardson’s act, acquired a new human and historic interest. For ever more, this picture will be a sign and a memorial of women’s determination to be free” [13]. But on this particular aspect, both sides probably overstated their case. The long term value of the painting, which was swiftly restored, was not adversely affected by the attack, but equally the prediction that it would acquire additional value as a sort of historical relic has not been borne out to any significant extent.

Although being regarded as the first known painting of a nude by a Spanish artist [8A] – the next one would not be until Goya's Naked Maja more than a century later – the Venus escaped censure from the Inquisition only by the fact that it was nominally of a mythological subject, and had been painted under the personal protection of the licentious Spanish King Philip IV. All in all, then, the idea of attacking it could well seem attractive to a fighter for women's rights. As an added bonus, attacking the painting would enable Richardson to come as near as possible to blood-shedding without actually infringing the suffragettes’ policy of not endangering human life [9].

Yet, from a public relations viewpoint, Richardson’s choice of target was actually quite problematic. The painting had only recently been acquired by the National Gallery after its previous owner, John Morritt MP of Rokeby Hall in Yorkshire (from which the painting gained its recent popular name) had put it up for sale. In private correspondence, Morritt had described the painting as his “fine picture of Venus’s backside”, and he had hung it prominently over his fireplace, which raised “the said backside to a considerable height” [10].

The £45,000 purchase price – a very substantial amount at the time – was raised by a widely-supported public subscription, including a crucial contribution by King Edward VII himself. The public therefore felt that it had a considerable financial, emotional and even patriotic stake in the painting. Its destruction was therefore hardly likely to attract popular support, particularly as the slashes were so disturbingly realistic in their impact.

At a more general level, people would be far more likely to form a strong attachment to a painting that they would with other suffragist targets of destruction, such as haystacks, sports pavilions, windows or letter boxes. As Rowena Fowler has pointed out, “it was not necessary to be an art lover or connoisseur to be disturbed by the threat to a valuable but vulnerable national possession; it was genuinely upsetting to see beautiful things spoiled and to find ‘great’ and ‘timeless’ works of art forced into proximity with the messiness of contemporary political conflict” [11]. The negative impact was increased by the brazenness of the attack and the fact that Richardson appeared to bask in her own publicity, taking pride in her action, rather than exhibiting what was felt to be a sufficient level of genuine remorse.

More prosaically, those who had contributed to the purchase of the painting would have been annoyed by reports that the attack had substantially reduced its value. The Keeper of the National Gallery had, for example, estimated that the value of the Venus had been reduced by ₤10-15,000 [12]. The WSPU counter-argued that “the Rokeby Venus has, because of Miss Richardson’s act, acquired a new human and historic interest. For ever more, this picture will be a sign and a memorial of women’s determination to be free” [13]. But on this particular aspect, both sides probably overstated their case. The long term value of the painting, which was swiftly restored, was not adversely affected by the attack, but equally the prediction that it would acquire additional value as a sort of historical relic has not been borne out to any significant extent.

Other reactions to the attack

In the light of all these considerations, it is perhaps not surprising that Richardson’s explanation for her actions, although cogently expressed, seemed to go completely over most people's heads. The almost universal press reaction [14] was predictably one of outrage, with many reports treating it as equivalent to a violent attack on an actual beautiful woman, rather than on a painted canvas, an odd inversion of Richardson’s argument. The language used was consistent with that of a sensational murder, with the Venus figure being described as a “victim”, and the damage as “cruel wounds”, “broad lacerations” or “ragged bruises”. One newspaper almost slaveringly described the nude figure as “the Goddess of Youth and Health, the embodiment of elastic strength and vitality – of the perfection of Womanhood at the moment when it passes from the bud to the flower” [15]. Similarly, Richardson herself was referred to as “Slasher Mary” or the “Ripper”. These allusions, of course, were evocative of the infamous Jack the Ripper murders some 25 years before [16], though not everyone took the matter quite so seriously (Fig 4).

Criticism of the attack even came from other suffrage associations. The more conservative National Union of Womens’ Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) censured Richardson’s apparent ignorance of the real value of the painting, and deplored “the spirit of revenge which has so poisoned the minds of a few of the supporters of the noblest and purest of all causes” [17].

One interestingly mixed reaction was by the painter Wyndham Lewis, who published an open letter to the suffragettes, expressing general support for their cause but giving them a rather patronising “word of advice” – “in destruction, as in other things, stick to what you understand. We make you a present of our vote, only leave works of art alone – you might someday destroy a good picture by accident…..Leave art alone, brave comrades!” His statement that “we make you a present of our vote” is interesting for its apparent assumption that “we” refers to males, and that the vote is a matter of discretionary benefaction, not right.

Directly after the attack, the National Gallery was closed to the public for two weeks, with many other major institutions such as the Tate, Hampton Court and Windsor Castle following suit. As presented in negative press reports, this meant that the ordinary public – not to mention the tourists so valued by the tourism industry – were being denied access to Britain’s artistic heritage, thanks to the wanton acts of “that woman”.

One interestingly mixed reaction was by the painter Wyndham Lewis, who published an open letter to the suffragettes, expressing general support for their cause but giving them a rather patronising “word of advice” – “in destruction, as in other things, stick to what you understand. We make you a present of our vote, only leave works of art alone – you might someday destroy a good picture by accident…..Leave art alone, brave comrades!” His statement that “we make you a present of our vote” is interesting for its apparent assumption that “we” refers to males, and that the vote is a matter of discretionary benefaction, not right.

Directly after the attack, the National Gallery was closed to the public for two weeks, with many other major institutions such as the Tate, Hampton Court and Windsor Castle following suit. As presented in negative press reports, this meant that the ordinary public – not to mention the tourists so valued by the tourism industry – were being denied access to Britain’s artistic heritage, thanks to the wanton acts of “that woman”.

A new wave of attacks on paintings

Richardson’s attack on the Rokeby Venus was destined to become one of the most notorious acts of iconoclasm in modern times. But she was not the first suffragette to target art galleries, nor the last. The year before, two other suffragettes, Lillian Forrester and Evelyn Manesta, who had previously engaged in a series of window smashings, had used hammers to smash the protective glass on thirteen of the biggest and most valuable works in the Manchester Art Gallery. In the process, four of the paintings themselves had been incidentally damaged, though this was apparently not the women’s intention [18]. Their attacks, like Richardson’s, were prompted by the government’s treatment of Mrs Pankhurst [19]. Both Forrester and Manesta were convicted and jailed on malicious damage charges, while an associate, Annie Briggs, was acquitted [20]. In sentencing Forrester and Manesta, the judge is reported to have said, “if the law would allow, I would send you round the world in a sailing ship as the best thing for you” (Fig 5).

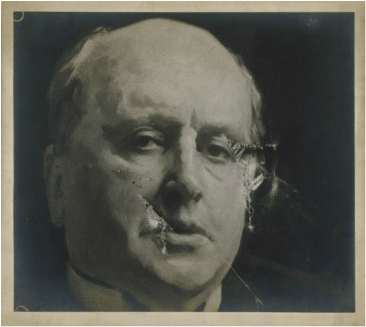

The Rokeby Venus attack had marked a significant escalation of these earlier incidents, as it was carried out with the deliberate intention of inflicting maximum damage to a particular, very famous, painting. The enormous publicity generated by Richardson's arrest and conviction prompted a rush of similar copy-cat attacks – fourteen more paintings would be slashed and nine women arrested between March and July 1914 [21]. The targets included the National Gallery, where Grace Marcon (aka Frieda Graham) damaged five paintings, including Giovanni Bellini's The Agony in the Garden and Gentile Bellini's Portrait of a Mathematician; and the John Singer Sargent portrait of Henry James in the Royal Academy, which was attacked with a chopper by Mary Wood, reportedly “an elderly woman of distinctly peaceable appearance”.

Wood’s stated rationale was that, “I have tried to destroy a valuable picture because I wish to show the public that they have no security for their property nor for their art treasures until women are given political freedom.” Unlike the situation with the Rokeby Venus, however, the subject matter of the painting appeared to have no special significance, as Henry James was seen as having broadly sympathetic feminist views. However, it has been suggested that “James became the target of this assault not for his writing, but because Sargent’s picture of him presented such an overbearing image of male authority”[22].

Wood’s stated rationale was that, “I have tried to destroy a valuable picture because I wish to show the public that they have no security for their property nor for their art treasures until women are given political freedom.” Unlike the situation with the Rokeby Venus, however, the subject matter of the painting appeared to have no special significance, as Henry James was seen as having broadly sympathetic feminist views. However, it has been suggested that “James became the target of this assault not for his writing, but because Sargent’s picture of him presented such an overbearing image of male authority”[22].

This assault was followed quickly by two more attacks at the same exhibition – Gertrude Mary Ansell’s hatchet job on Herkomer’s portrait of the Duke of Wellington (whereabouts now unknown), which earned her six months imprisonment in which, reportedly, she was forcibly fed an almost unbelievable 236 times; and Mary Spencer’s use of a meat cleaver to dissect Primavera, a teasing nude by Clausen. Elsewhere, five paintings in the Venetian Room at the National Gallery were slashed; and attacks were carried out at the Doré Gallery, at Birmingham City Art Gallery, on Lavel’s portrait of George V, and on Millais’ portrait of Carlyle.

The women’s suffrage movement

The wider context of all these attacks was the militant campaign being waged by the WSPU, which had been founded by Mrs Pankhurst, together with her daughter Christabel, back in 1903. The WSPU’s aim was to achieve the vote for women on the same basis as that currently applying to men, who qualified if they were aged 21, and satisfied a residency and property qualification [23].

The Canadian-raised Richardson had joined the WSPU after hearing Mrs Pankhurst speaking at the Albert Hall. She likened the change to enlisting in a “holy crusade” [24]. Using the name “Polly Dick”, Richardson embarked on an active career including window smashing at the Home Office, bombing a railway station and carrying out several episodes of arson. All told, she was arrested nine times, and received prison terms totalling more than three years. She had gone on a hunger strike in prison and was one of the first women to undergo being forcibly fed. She had actually been out on licence from Holloway Prison when she carried out the Rokeby Venus attack.

The WSPU was one of a number of women’s suffrage associations active at the time, the most notable being the much larger National Union of Womens’ Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) led by Millicent Fawcett. The Pankhursts had become frustrated that although the suffrage movement had been active for many years, it seemed to have made little headway. Adopting the slogan “Deeds, not words”, they believed that there would only be progress if there was more direct and disruptive action. Fawcett and the NUWSS, on the other hand, preferred to continue using persuasion and negotiation.

Many members of the various suffrage groups were concerned not just with the vote, but also with other issues particularly affecting women. There were fundamental differences not only between the groups, but within them. Should they be “pro” men or “anti” men (or neither)? Should they stand for sexual “purity”, or for sexual independence? Was marriage desirable or was it a form of slavery? Were women equal to men, or were they superior, or were they just “special”[25]? These differences, often passionately espoused, made it difficult for a clear or unified message to develop. To some extent, the issue of the vote provided some consistency of view but, even here there were basic differences of opinion. In addition to the different courses set by the WSPU and the NUWSS, there were questions over whether the franchise should be restricted to married women, or to women with property, or women over a certain age; or whether, as some members of the Left believed, men and women should enjoy universal suffrage of the type enjoyed today.

The Canadian-raised Richardson had joined the WSPU after hearing Mrs Pankhurst speaking at the Albert Hall. She likened the change to enlisting in a “holy crusade” [24]. Using the name “Polly Dick”, Richardson embarked on an active career including window smashing at the Home Office, bombing a railway station and carrying out several episodes of arson. All told, she was arrested nine times, and received prison terms totalling more than three years. She had gone on a hunger strike in prison and was one of the first women to undergo being forcibly fed. She had actually been out on licence from Holloway Prison when she carried out the Rokeby Venus attack.

The WSPU was one of a number of women’s suffrage associations active at the time, the most notable being the much larger National Union of Womens’ Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) led by Millicent Fawcett. The Pankhursts had become frustrated that although the suffrage movement had been active for many years, it seemed to have made little headway. Adopting the slogan “Deeds, not words”, they believed that there would only be progress if there was more direct and disruptive action. Fawcett and the NUWSS, on the other hand, preferred to continue using persuasion and negotiation.

Many members of the various suffrage groups were concerned not just with the vote, but also with other issues particularly affecting women. There were fundamental differences not only between the groups, but within them. Should they be “pro” men or “anti” men (or neither)? Should they stand for sexual “purity”, or for sexual independence? Was marriage desirable or was it a form of slavery? Were women equal to men, or were they superior, or were they just “special”[25]? These differences, often passionately espoused, made it difficult for a clear or unified message to develop. To some extent, the issue of the vote provided some consistency of view but, even here there were basic differences of opinion. In addition to the different courses set by the WSPU and the NUWSS, there were questions over whether the franchise should be restricted to married women, or to women with property, or women over a certain age; or whether, as some members of the Left believed, men and women should enjoy universal suffrage of the type enjoyed today.

Political and popular support

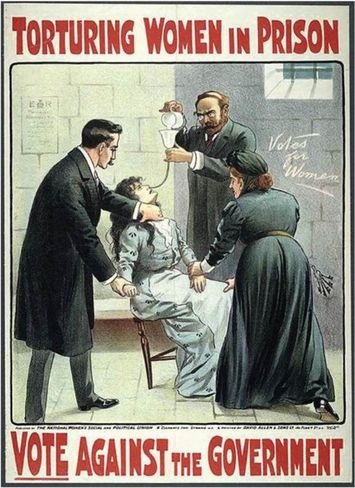

As it happened, women’s suffrage was actually surprisingly well supported, at least in theory, in the House of Commons, mainly among the Liberals. But there were seemingly implacable opponents in the House of Lords and, crucially, the Prime Minister was vehemently opposed. The Royal Family, too. were not supportive – Queen Mary scorned what she described as “those horrid suffragettes” and was particularly alienated by their militancy [26], and it was the King himself who in 1909 had suggested introducing the practice of forcibly feeding those imprisoned suffragettes who went on hunger strikes. This gruesomely cruel procedure was normally accomplished by physically (and often roughly) restraining the prisoner and force-feeding her with a tube inserted into her mouth or nose. The process was intrusive, humiliating, painful and often induced vomiting. Some victims suffered long term health problems as a result [27]. Confronting images of force-feeding would eventually become political weapons that were used against the government (Fig 5A).

The Independent Labor Party was broadly sympathetic to suffragette views, though was wary of the Pankhurst’s exclusion of unpropertied women from the vote, and was concerned with whether “hordes of liberated women” entering the workforce would lead to competition for jobs and lower wages. It seemed that all the political parties managed to convince themselves to hold the mutually contradictory view that women's votes would favour “the other side”, with the result being that suffrage proposals kept getting derailed or delayed. Viewed in retrospect, this parliamentary impasse reflected a combination of prejudice, apprehension (justified or not) and collective dithering.

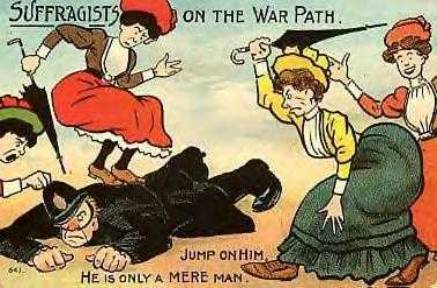

Among the public, opinion was split. Many people believed that women’s suffrage was simply not a priority issue. While there was a significant level of support, particularly among women and the Left, there were also predictable claims – by some women as well as by men – that it would lead to the end of British civilisation and the demasculation of men. These claims were typically accompanied by portrayals of suffragettes as mannish, unfeminine, sexually-starved, ugly and obsessed with power (Fig 6).

Among the public, opinion was split. Many people believed that women’s suffrage was simply not a priority issue. While there was a significant level of support, particularly among women and the Left, there were also predictable claims – by some women as well as by men – that it would lead to the end of British civilisation and the demasculation of men. These claims were typically accompanied by portrayals of suffragettes as mannish, unfeminine, sexually-starved, ugly and obsessed with power (Fig 6).

Negative presentations such as these were strongly reminiscent of the attitudes taken to the advent in the 1890s of women’s bicycling (see our article on Toulouse Lautrec, the bicycle and the women's movement). Suffragettes therefore needed to be prepared for abuse and possibly violence from opponents on any their public appearances.

The Pankhurst strategy

Mrs Pankhurst, possibly influenced by the campaign run by Charles Stewart Parnell in seeking Home Rule for Ireland [28], based the WSPU’s strategy on being focused, persistent, obstructionist and strongly led. She often referred to the WSPU as a “volunteer army”, and the campaign as a war, with the aim being to bring the government to its knees. As with Parnell, anyone who had doubts was out. This often translated to an attitude that “if you disagree at all with me, you don’t belong”. This autocratic approach certainly had its strengths, but as time went by, it also proved to have its weaknesses – unlike Parnell, the Pankhursts appeared to be being neither willing nor able to negotiate.

The WSPU’s more militant tactics were devised mainly by Christabel Pankhurst. One key aim was to obtain publicity through getting imprisoned. Christabel herself deliberately disturbed a Liberal Party meeting and reportedly spat at a policeman. Refusing to pay the resultant fine (or to have anyone else pay it for her), she achieved the desired martyred status by being sent to Strangeways jail. The whole episode, including the celebrations on Christabel’s ultimate release, drew a level of publicity and excitement that even Millicent Fawcettt acknowledged twenty years of peaceful propaganda had failed to produce.

A concerted program of heckling government speakers began, with aggressive picketing, noisy interruptions and scuffles in which the participating suffragettes themselves often became the victims [29]. In furtherance of the cause, WSPU branches continued to be set up, public meetings held, marches and rousing speeches made. A distinctive “uniform” was devised, with a long white dress highlighted by purple and green. In massed displays or marches, it presented an impressive spectacle.

The WSPU’s more militant tactics were devised mainly by Christabel Pankhurst. One key aim was to obtain publicity through getting imprisoned. Christabel herself deliberately disturbed a Liberal Party meeting and reportedly spat at a policeman. Refusing to pay the resultant fine (or to have anyone else pay it for her), she achieved the desired martyred status by being sent to Strangeways jail. The whole episode, including the celebrations on Christabel’s ultimate release, drew a level of publicity and excitement that even Millicent Fawcettt acknowledged twenty years of peaceful propaganda had failed to produce.

A concerted program of heckling government speakers began, with aggressive picketing, noisy interruptions and scuffles in which the participating suffragettes themselves often became the victims [29]. In furtherance of the cause, WSPU branches continued to be set up, public meetings held, marches and rousing speeches made. A distinctive “uniform” was devised, with a long white dress highlighted by purple and green. In massed displays or marches, it presented an impressive spectacle.

Increasingly, as time went by, the WSPU had drifted away from some of its original links with the Left, and fostered its connections with “well-bred” middle and upper class women (like the Pankhursts themselves). This type of women generated more publicity, more sympathy and more converts when they went to jail than working class women and girls did. Christabel correctly judged that it was the sight of the symbols of bourgeois ultra-respectability taking to the streets which would get under the government’s skin like nothing else [30]. Eventually, formal links with the labour movement were terminated in 1907.

The WSPU also developed more direct threats to public order, such as smashing windows in government offices, or throwing stones. Mrs Pankhurst herself was regularly being arrested or imprisoned for various offences. One imprisoned suffragette, on her own initiative, went on a hunger strike, starting a wave of imitators. Mrs Pankhurst (though not Christabel) endured many of these, suffering considerably, though was never subject to force- feeding. By this stage, Millicent Fawcett and the NUWSS had completely distanced themselves, registering strong objections to the WSPU’s increasingly aggressive tactics.

The WSPU also developed more direct threats to public order, such as smashing windows in government offices, or throwing stones. Mrs Pankhurst herself was regularly being arrested or imprisoned for various offences. One imprisoned suffragette, on her own initiative, went on a hunger strike, starting a wave of imitators. Mrs Pankhurst (though not Christabel) endured many of these, suffering considerably, though was never subject to force- feeding. By this stage, Millicent Fawcett and the NUWSS had completely distanced themselves, registering strong objections to the WSPU’s increasingly aggressive tactics.

The militancy increases

As time went by, still with no apparent progress in Parliament, the WSPU's level of militancy was upped yet again. By 1912, the strategy was now no longer just to shock the government but to force it to legislate by the threat of violent attacks. In Lisa Tickner’s words, the WSPU became focused on daring deeds of furtive guerrilla activity performed by a small group of individuals who were tasting what Christabel referred to as “the exaltation, the rapture of battle”[31]. This “spectacular radicalisation” [32] was centred round the destruction of property, widespread arson, firing pillar-boxes, burning buildings, boathouses, pavilions, setting off bombs and later – as we have already seen – attacking paintings. In the Pankhursts' view, the public itself had only itself to blame for this if they stood by and allowed women’s suffrage to continue being denied. The government reacted by jailing Mrs Pankhurst for nine months, and Christina fled to Paris where she continued the campaign from a distance.

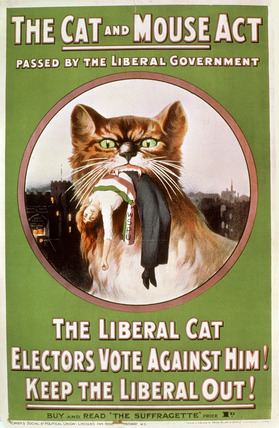

Apart from the daring and courage needed to carry out these acts, the militants knew that the prison conditions they could face could be primitive, and that their hunger strikes could be arduous and medically harmful. But those hunger strikes also created a sensitive problem for the Liberal government. Its novel solution was to pass legislation which enabled imprisoned suffragettes to be released on licence on account of ill-health, but to be re-imprisoned once they had recovered [33]. This “letting them go, then catching them again” policy became known as “The Cat and Mouse Act” and was exploited derisively by the suffragettes in targeting Liberal candidates (Fig 8) [34].

Apart from the daring and courage needed to carry out these acts, the militants knew that the prison conditions they could face could be primitive, and that their hunger strikes could be arduous and medically harmful. But those hunger strikes also created a sensitive problem for the Liberal government. Its novel solution was to pass legislation which enabled imprisoned suffragettes to be released on licence on account of ill-health, but to be re-imprisoned once they had recovered [33]. This “letting them go, then catching them again” policy became known as “The Cat and Mouse Act” and was exploited derisively by the suffragettes in targeting Liberal candidates (Fig 8) [34].

he level to which violence had risen was demonstrated by Christina’s exultant summary of the 141 acts of destruction chronicled in the press in just the first seven months of 1914:

“The destruction wrought …excelled that of the previous year. Three Scotch castles were destroyed by fire on a single night. The Carnegie Library in Birmingham was burnt. The Rokeby Venus … was mutilated by Mary Richardson. Romney’s Master Thornhill, in the Birmingham Art Gallery was slashed by Bertha Ryland, daughter of an early suffragist. Carlyle’s portrait of Millais [sic, actually the reverse] in the National Portrait Gallery, and numbers of other pictures were attacked, a Bartolozzi drawing in Doré Gallery being completely ruined. Many large empty houses in all parts of the country were set on fire, including Redlynch House, Somerset, where the damage was estimated at £40,000. Railway stations, piers, sports pavilions, haystacks were set on fire. Attempts were made to blow up reservoirs. A bomb exploded in Westminster Abbey, and in the fashionable church of St George’s, Hanover Square, where a famous stained glass window from Malines was damaged”[35].

“The destruction wrought …excelled that of the previous year. Three Scotch castles were destroyed by fire on a single night. The Carnegie Library in Birmingham was burnt. The Rokeby Venus … was mutilated by Mary Richardson. Romney’s Master Thornhill, in the Birmingham Art Gallery was slashed by Bertha Ryland, daughter of an early suffragist. Carlyle’s portrait of Millais [sic, actually the reverse] in the National Portrait Gallery, and numbers of other pictures were attacked, a Bartolozzi drawing in Doré Gallery being completely ruined. Many large empty houses in all parts of the country were set on fire, including Redlynch House, Somerset, where the damage was estimated at £40,000. Railway stations, piers, sports pavilions, haystacks were set on fire. Attempts were made to blow up reservoirs. A bomb exploded in Westminster Abbey, and in the fashionable church of St George’s, Hanover Square, where a famous stained glass window from Malines was damaged”[35].

While officially the WSPU was committed to the sanctity of human life, the increasingly violent trend suggested that the Pankhursts were having some difficulty in controlling their more enthusiastic (or fanatical) supporters. In 1913, Emily Wilding Davison was famously killed when she ventured onto the race track during the running of the Epsom Derby (Fig 10). It was an extraordinarily courageous, if rash, act, but one which could well have led to deaths other than her own [36]. In February 1914, a suffragette attacked Lord Wensleydale, a Liberal peer, after she mistook him for the Prime Minister. Two suffragettes used horsewhips on the deputy governor of Holloway Prison. A train guard was badly burned by sulphuric acid after an explosion among mail bags caused by a suffragette-designed device [37]. It was becoming increasingly difficult to see how this level of militancy could be further continued or increased without it resulting in some sort of full-scale disaster.

Increasingly too, initiatives were starting to be taken by individual members, rather than the Pankhursts. So, for example, the hunger strike strategy was initiated by Marion Wallace-Dunlop, and only later endorsed by the WSPU. Similarly, a boycott of the national census was initially disapproved of by the Pankhursts but later approved because so many members wanted to participate.

Major internal organisational problems had also developed. Of course, in any protest organisation, some level of internal conflict is only to be expected. However the number of key supporters who had split from the organisation kept on mounting. Back in 1907 there had been a major split led by Teresa Billington-Grieg, protesting about the increasingly autocratic control of the WSPU, and setting up a rival body, the Womens Freedom League (WFL). Another split in early 1914 produced the United Suffragists. Long-time key supporters such as the Pethic-Lawrences objected to the increasing violence and left in 1912; Sylvia Pankhurst, the most left-leaning of the family, also departed or was pushed out over ideological differences, including the increasing violence and the issue of pacifism; she went on to form her own movement, the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). Christina herself was still absent in Paris. For some, all these trends suggested that by August 1914 there was a possibility that the WSPU was beginning to teeter out of control.

Major internal organisational problems had also developed. Of course, in any protest organisation, some level of internal conflict is only to be expected. However the number of key supporters who had split from the organisation kept on mounting. Back in 1907 there had been a major split led by Teresa Billington-Grieg, protesting about the increasingly autocratic control of the WSPU, and setting up a rival body, the Womens Freedom League (WFL). Another split in early 1914 produced the United Suffragists. Long-time key supporters such as the Pethic-Lawrences objected to the increasing violence and left in 1912; Sylvia Pankhurst, the most left-leaning of the family, also departed or was pushed out over ideological differences, including the increasing violence and the issue of pacifism; she went on to form her own movement, the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). Christina herself was still absent in Paris. For some, all these trends suggested that by August 1914 there was a possibility that the WSPU was beginning to teeter out of control.

A sudden change of focus

In his New Year message for 1914, the Archbishop of York warned that it could well prove to be “a very fateful year in the history of our land”. His concern was with the prospect of three major challenges to social order in Britain – the threat of industrial strife and paralysis resulting from continuous strikes; the vexed issue of Home Rule for Ireland; and the increasingly destructive militant tactics of the suffragette movement [38]. The Archbishop was not to know that another quite different and cataclysmic event would soon overwhelm all these issues.

That event, of course, was the sudden outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. It marked a crucial turning point for Britain, and for the suffragette cause. The government almost immediately declared that all remaining suffragette prisoners would be released. In return, Mrs Pankhurst suspended militancy, requesting all WSPU members to devote their efforts to supporting the war effort. In effect, the WSPU’s militant campaign stopped in its tracks.

The prosecution of the War, which had previously been considered to be “God’s vengeance upon the people who held women in subjection” (Christabel) or “not women’s way”, became Mrs Pankhurst’s new passion. It was a change of focus which had not been anticipated by many [39]. She rejected “pacifism at all costs” and began making recruiting speeches, lobbying vigorously for military conscription, and criticising “weak-kneed” politicians who were not aggressive enough. Her view was that “every man of fighting age should prepare himself to redeem his word to women”. Her supporters – though evidently not Mrs Pankhurst herself [40] – reportedly handed out white feathers, a symbol of cowardice, to young men who were not in uniform in the hope of shaming or humiliating them into enlisting. Mrs Pankhurst also vigorously promoted, with government support, the involvement of women in the wartime workforce (including strikebreaking) and opposing strike action.

Her support for the men who actually were fighting overseas was such that she considered that it was more important to ensure that those men received the vote – at risk because they necessarily could no longer satisfy the residency requirement – than any issue of the vote for women. In 1915, her increasingly ultra-nationalistic approach was reflected by the change of the WSPU’s newspaper’s name from The Suffragette to Britannia, with the byline “for King, for Country, for Freedom”. According to the new policy, it was “a thousand times more the duty of the militant suffragettes to fight the Kaiser for the sake of liberty than it was to fight anti-suffrage Governments” [41]. Mrs Pankhurst involved herself in opposing Bolshevism, calling for abolition of trade unions, promoting equal rights for women, looking after the interests of war babies and campaigning for chastity and self-control.

This radical change of focus, however, had been costing the WSPU support among those former members who were pacifists, or opposed conscription, or who were not ultra-nationalist. With dwindling support, and despite a rebranding as The Women’s Party, it was eventually disbanded altogether. Mrs Pankhurst would eventually join the Conservative Party in 1925.

That event, of course, was the sudden outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. It marked a crucial turning point for Britain, and for the suffragette cause. The government almost immediately declared that all remaining suffragette prisoners would be released. In return, Mrs Pankhurst suspended militancy, requesting all WSPU members to devote their efforts to supporting the war effort. In effect, the WSPU’s militant campaign stopped in its tracks.

The prosecution of the War, which had previously been considered to be “God’s vengeance upon the people who held women in subjection” (Christabel) or “not women’s way”, became Mrs Pankhurst’s new passion. It was a change of focus which had not been anticipated by many [39]. She rejected “pacifism at all costs” and began making recruiting speeches, lobbying vigorously for military conscription, and criticising “weak-kneed” politicians who were not aggressive enough. Her view was that “every man of fighting age should prepare himself to redeem his word to women”. Her supporters – though evidently not Mrs Pankhurst herself [40] – reportedly handed out white feathers, a symbol of cowardice, to young men who were not in uniform in the hope of shaming or humiliating them into enlisting. Mrs Pankhurst also vigorously promoted, with government support, the involvement of women in the wartime workforce (including strikebreaking) and opposing strike action.

Her support for the men who actually were fighting overseas was such that she considered that it was more important to ensure that those men received the vote – at risk because they necessarily could no longer satisfy the residency requirement – than any issue of the vote for women. In 1915, her increasingly ultra-nationalistic approach was reflected by the change of the WSPU’s newspaper’s name from The Suffragette to Britannia, with the byline “for King, for Country, for Freedom”. According to the new policy, it was “a thousand times more the duty of the militant suffragettes to fight the Kaiser for the sake of liberty than it was to fight anti-suffrage Governments” [41]. Mrs Pankhurst involved herself in opposing Bolshevism, calling for abolition of trade unions, promoting equal rights for women, looking after the interests of war babies and campaigning for chastity and self-control.

This radical change of focus, however, had been costing the WSPU support among those former members who were pacifists, or opposed conscription, or who were not ultra-nationalist. With dwindling support, and despite a rebranding as The Women’s Party, it was eventually disbanded altogether. Mrs Pankhurst would eventually join the Conservative Party in 1925.

Finally getting the vote ...

In the meantime, after more than three years of War, Parliament had overcome its vacillation, and finally acted on the suffrage. The Representation of the People Act 1918, granting the right to vote to women aged 30 or over (compared to the men's age of 21), became law on 6 February 1918. This allowed over 8 million women to vote. To be eligible, women had to be householders, householders’ wives, graduates or occupiers of property with an annual rent of 5 pounds or more. However, the law was unclear as to whether it granted women the right to also stand as parliamentary candidates. This was only confirmed in November 1918 [42], but as an election had already been called for December, prospective female candidates had only a very short time to decide on their party affiliation (if any), find a seat, organise support and nominate. In the event, only 17 women stood, including Christabel, but only one was elected. Ironically, this was Constance Markievicz who, as a member of Sinn Fein, refused to take an oath of allegiance and never took her seat [43]. The first woman to actually do so was US-born socialite Nancy Astor, after a 1919 by-election.

Full suffrage was not granted until ten years later, when The Equal Franchise Act 1928 lowered the voting age for women to 21, thus aligning it with males. Over 15 million women were now enabled to vote. Mrs Pankhurst, however, did not live to see the day; she had died just days before.

Full suffrage was not granted until ten years later, when The Equal Franchise Act 1928 lowered the voting age for women to 21, thus aligning it with males. Over 15 million women were now enabled to vote. Mrs Pankhurst, however, did not live to see the day; she had died just days before.

… and sharing the credit

The WSPU is often considered to be the prime motivating force in the granting of the vote. However, it appears that the issue may be considerably more nuanced than this. It was certainly true that the WSPU could claim credit for the crucial raising of consciousness of the issue as one worthy of serious consideration; for demonstrating that there was significant support for it among women themselves; for mobilising, empowering and energising many women in the cause; and for providing forceful and charismatic leadership. But this is not necessarily the same as showing that it was effective in actually changing the minds of either the politicians or the general public. On this aspect, a number of other important factors were also involved.

The first of these was women’s involvement in the war effort, arising from the inevitable manpower shortages [44]. This shortage of men led to some fundamental changes in the labour market and the general perception of the role of women. Many women began to take on jobs which had previously been exclusively male. Women became conductors on buses and trains. They performed vital and dangerous work in munitions factories, shipbuilding and the heavy labour of unloading coal. As the NUWSS's Millicent Fawcett pointed out, the war “opened up both opportunities and men’s minds. It had made both men and women aware of the waste involved in condemning women to work which needed only mediocre intelligence”[45].

A number of politicians stated that this was in fact the main factor in their decision. The Conservatives leader Balfour, for example, claimed that the grant of the women’s suffrage was “mainly due to the universal recognition of the magnificent work performed by the women of Britain in the country’s cause”. The previously recalcitrant Asquith also attributed the change to women's war effort [46]. However, this view is debatable – it may be that the war effort provided a convenient excuse for politicians to explain why they had changed their vote, without having to admit that their earlier attitudes were mistaken, and without having to give credit to the suffrage organisations. The war-induced cessation of militant suffragette activities also enabled politicians such as Asquith to implement change without appearing to be forced into it.

It was also relevant that there had been a change in the actual composition of Parliament, reflecting more members in favour, and the ending of Asquith’s personal opposition. Crucially, too, the form of suffrage that was granted in 1918 was actually very limited. The age and property restrictions meant, for example, that most female munitions workers would remain disenfranchised because they were under 30. Many wavering politicians were also comforted by the (untested) belief that those older women who would receive the vote would be less likely to support other dangerous feminist or radical reforms.

The other principal factor was Millicent Fawcett’s efforts over many years – often behind the scenes – in seeking a workable consensus. Some commentators have suggested that this contribution, admittedly far less exciting than the WSPU’s exploits, has been unjustifiably devalued. Melanie Phillips, for example, goes so far as to suggest that Fawcett “could justifiably claim the lion’s share of the credit” for the granting of the vote [47].

It also needs to be appreciated that women’s role in a more general sense was expanding. Women were moving into higher education and previously inaccessible professions. Achieving a prominent or independent position was slowly becoming normalised. Specific moves toward women’s suffrage had also gained strength in other developed countries. It was not as if Britain was leading the world in this change – women had already gained the vote in countries like New Zealand (1893), Australia (1894-1902), Finland (1906), Norway (1907) and some States of the United States (1869 onwards) a generation or more before.

The efficacy of the highly militant strategy from 1912-14, as distinct from the earlier less violent militancy, is also a matter of special dispute. It should not simply be assumed without question that the increased violence of the attacks, or the threat of their resumption, forced the government into action. It is possible that it had no net effect on the result, and it is even plausible that it actually delayed any change. This would apply with even more force with the attacks on paintings. For reasons we have previously discussed relating to the special status of these objects, and despite the intellectual rationalisations made by the perpetrators and the WSPU, it is likely that these attacks on popularly-valued cultural items – an activity more usually associated with terrorists, uncaring vandals, totalitarian regimes, conquerors or the insane – may have only confirmed, rather than changed, anti-suffrage views [48]. □

End of Pt 1 -- now go to Pt 2: The Strange Allure of Fascism

© Philip McCouat, 2014, 2015, 2016.

The first of these was women’s involvement in the war effort, arising from the inevitable manpower shortages [44]. This shortage of men led to some fundamental changes in the labour market and the general perception of the role of women. Many women began to take on jobs which had previously been exclusively male. Women became conductors on buses and trains. They performed vital and dangerous work in munitions factories, shipbuilding and the heavy labour of unloading coal. As the NUWSS's Millicent Fawcett pointed out, the war “opened up both opportunities and men’s minds. It had made both men and women aware of the waste involved in condemning women to work which needed only mediocre intelligence”[45].

A number of politicians stated that this was in fact the main factor in their decision. The Conservatives leader Balfour, for example, claimed that the grant of the women’s suffrage was “mainly due to the universal recognition of the magnificent work performed by the women of Britain in the country’s cause”. The previously recalcitrant Asquith also attributed the change to women's war effort [46]. However, this view is debatable – it may be that the war effort provided a convenient excuse for politicians to explain why they had changed their vote, without having to admit that their earlier attitudes were mistaken, and without having to give credit to the suffrage organisations. The war-induced cessation of militant suffragette activities also enabled politicians such as Asquith to implement change without appearing to be forced into it.

It was also relevant that there had been a change in the actual composition of Parliament, reflecting more members in favour, and the ending of Asquith’s personal opposition. Crucially, too, the form of suffrage that was granted in 1918 was actually very limited. The age and property restrictions meant, for example, that most female munitions workers would remain disenfranchised because they were under 30. Many wavering politicians were also comforted by the (untested) belief that those older women who would receive the vote would be less likely to support other dangerous feminist or radical reforms.

The other principal factor was Millicent Fawcett’s efforts over many years – often behind the scenes – in seeking a workable consensus. Some commentators have suggested that this contribution, admittedly far less exciting than the WSPU’s exploits, has been unjustifiably devalued. Melanie Phillips, for example, goes so far as to suggest that Fawcett “could justifiably claim the lion’s share of the credit” for the granting of the vote [47].

It also needs to be appreciated that women’s role in a more general sense was expanding. Women were moving into higher education and previously inaccessible professions. Achieving a prominent or independent position was slowly becoming normalised. Specific moves toward women’s suffrage had also gained strength in other developed countries. It was not as if Britain was leading the world in this change – women had already gained the vote in countries like New Zealand (1893), Australia (1894-1902), Finland (1906), Norway (1907) and some States of the United States (1869 onwards) a generation or more before.

The efficacy of the highly militant strategy from 1912-14, as distinct from the earlier less violent militancy, is also a matter of special dispute. It should not simply be assumed without question that the increased violence of the attacks, or the threat of their resumption, forced the government into action. It is possible that it had no net effect on the result, and it is even plausible that it actually delayed any change. This would apply with even more force with the attacks on paintings. For reasons we have previously discussed relating to the special status of these objects, and despite the intellectual rationalisations made by the perpetrators and the WSPU, it is likely that these attacks on popularly-valued cultural items – an activity more usually associated with terrorists, uncaring vandals, totalitarian regimes, conquerors or the insane – may have only confirmed, rather than changed, anti-suffrage views [48]. □

End of Pt 1 -- now go to Pt 2: The Strange Allure of Fascism

© Philip McCouat, 2014, 2015, 2016.

End Notes for Pt 1

1. The following account is based largely on Lynda Nead, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity and Sexuality, Routledge, London 1992 at 34ff; and Mary Richardson, Laugh a Defiance, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1953, at 165ff.

2. (1647-51); more correctly known as Venus at her Mirror or, in the original Spanish, La Venus del Espejo.

3. London Times, 11 March 2014, quoted in Nead, op cit at 35.

4. Nead, op cit at 37.

5. Quoted in Dano Gamboni, The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution, Reaktion Books, London, 1997, at 94.

6. Richardson, op cit.

7. Quoted in Nead, op cit at 37.

8. Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, “A nude for the pious king”, in What Great Paintings Say, Vol 1, Taschen, Köln, 2003, at 255-259.

8A. However it has been reported that El Greco's Toledo-based son, Jorge Manuel Theotocópuli, painted a Death of Holy Mary Magdalene (1607-19) which features a full-frontal nude, though with strategically-positioned arms and hair: The Art Newspaper, No 259, July/August 2014, p 8.

9. Gamboni, op cit at 96.

10. Letter by Morritt to Sir Walter Scott, quoted in Dawson W Carr (ed), Velasquez, National Gallery, London 2006, at 99. For details of the sale of the Rokeby Venus, see Barbara Pezzini, "Days with Velásquez", The Burlington Magazine, May 2016 at 158.

11. Rowena Fowler, “Why Did Suffragettes Attack Works of Art?”, Journal of Women’s History, Vol 2, No 3 Winter 1991, 109.

12. Fowler, op cit.

13. Christabel Pankhurst in The Suffragette, 20 March 1914: quoted in Fowler, op cit.

14. Of the national press, only the Daily Herald was at all sympathetic; see Fowler, op cit.

15. Quoted in Gamboni, op cit, at 96.

16. Nead, op cit at 38.

17. “An Irreparable Loss”, in The Common Cause, 13 March 1914; quoted in Fowler, op cit.

18. For a partial list of the damaged paintings, largely pre-Raphaelite or late Victorian works, see Manchester Art Gallery, “Wonder Women: Radical Manchester”, http://www.manchestergalleries.org/the-collections/wonder-women/ [accessed May 2014].

19. On the previous day, she had been sentenced to three years penal servitude for inciting “persons unknown” to commit arson by burning down buildings. Other women in Manchester had also protested by pouring ink into 11 post boxes, damaging 250 letters: see Manchester Art Gallery, op cit.

20. Briggs had supported but not participated in the attack.

21. Fowler, op cit.

22. Carter Ratcliff, John Singer Sargent, Abbeville Press, New York, 1982, 231 cited in Fowler, op cit.

23. This in fact enabled only a minority of men, predominantly from the middle and upper classes, to qualify.

24. Richardson, op cit at 96.

25. Phillips, op cit at xi.

26. 1913 letter cited in Kate Adie, Fighting on the Home Front: The Legacy of Women in World War One, Hachette UK, 2013.

27. For a graphic first-person account see Constance Lytton, Prisons and Prisoners, William Heinemann, London. 1914; extracted in Eyewitness to History (ed John Carey), Avon Books, New York, 1987 at 423ff.

28. Phillips, opp cit at 141.

29. Phillips, op cit at 176.

30. Phillips, op cit at 186.

31. Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907-14, Chatto and Windus, London, 1987, at 135.

32. Gamboni, op cit at 95.

33. Prisoners Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health Act 1913.

34. As previously noted, Mary Richardson had actually been out of prison on licence under this Act when she carried out her Rokeby Venus attack.

35. Gamboni, op cit at 95-6.

36. Mary Richardson claimed that she was present at this event, though this has been disputed.

37. Mark Bostridge, “1914: Why war caught Britain cold”, BBC History Magazine, January 2014, 22–27. More generally, see the same author's The Fateful Year: England 1914, Penguin, London, 2014.

38. Bostridge, op cit (BBC History) at 23.

39. For differing views on the consistency of her position compare Phillips, op cit at 291ff and June Purvis, Mrs Pankhurst: a Biography, Routledge, London, 2002 at 268ff. Phillips describes it as a “spectacular volte-face”, whereas Purvis argues that it was not an abandonment of feminism, and was explicable as the act of a “patriotic feminist”.

40. Purvis, op cit at 271.

41. Susan and Angela McPherson, Mosley’s Old Suffragette: A Biography of Norah Dacre Fox, Revised edn 2011, at 87; Purvis, op cit.

42. The Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918.

43. Purvis, op cit at 312-4.

44. Phillips, op cit at 303. This situation is reminiscent of the expansion of women’s economic role in the wake of the manpower shortages caused by the London outbreak of the Black Death in 1439: see Caroline Barron, “Medieval queens of industry”, BBC History Magazine, June 2014, 30-33.

45. Phillips, op cit at 303.

46. Phillips, op cit at 299-302.

47. Phillips, op cit at 303.

48. Respected historians differ widely on the relative importance of the various factors. For examples of some differing viewpoints, see Purvis, op cit at 307ff; Phillips, op cit at 304ff; and Martin Pugh, The March of the Women, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2002, at 252ff. For recent books on various aspects of women's suffrage, see Jad Adams, Women and the Vote: A World History, Oxford University Press, 2014; and Jill Liddington, Vanishing for the Vote: Suffrage, citizenship and the Battle for the Census, Manchester University Press, 2014.

© Philip McCouat, 2014, 2015, 2016

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to Home

2. (1647-51); more correctly known as Venus at her Mirror or, in the original Spanish, La Venus del Espejo.

3. London Times, 11 March 2014, quoted in Nead, op cit at 35.

4. Nead, op cit at 37.

5. Quoted in Dano Gamboni, The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution, Reaktion Books, London, 1997, at 94.

6. Richardson, op cit.

7. Quoted in Nead, op cit at 37.

8. Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, “A nude for the pious king”, in What Great Paintings Say, Vol 1, Taschen, Köln, 2003, at 255-259.

8A. However it has been reported that El Greco's Toledo-based son, Jorge Manuel Theotocópuli, painted a Death of Holy Mary Magdalene (1607-19) which features a full-frontal nude, though with strategically-positioned arms and hair: The Art Newspaper, No 259, July/August 2014, p 8.

9. Gamboni, op cit at 96.

10. Letter by Morritt to Sir Walter Scott, quoted in Dawson W Carr (ed), Velasquez, National Gallery, London 2006, at 99. For details of the sale of the Rokeby Venus, see Barbara Pezzini, "Days with Velásquez", The Burlington Magazine, May 2016 at 158.

11. Rowena Fowler, “Why Did Suffragettes Attack Works of Art?”, Journal of Women’s History, Vol 2, No 3 Winter 1991, 109.

12. Fowler, op cit.

13. Christabel Pankhurst in The Suffragette, 20 March 1914: quoted in Fowler, op cit.

14. Of the national press, only the Daily Herald was at all sympathetic; see Fowler, op cit.

15. Quoted in Gamboni, op cit, at 96.

16. Nead, op cit at 38.

17. “An Irreparable Loss”, in The Common Cause, 13 March 1914; quoted in Fowler, op cit.

18. For a partial list of the damaged paintings, largely pre-Raphaelite or late Victorian works, see Manchester Art Gallery, “Wonder Women: Radical Manchester”, http://www.manchestergalleries.org/the-collections/wonder-women/ [accessed May 2014].

19. On the previous day, she had been sentenced to three years penal servitude for inciting “persons unknown” to commit arson by burning down buildings. Other women in Manchester had also protested by pouring ink into 11 post boxes, damaging 250 letters: see Manchester Art Gallery, op cit.

20. Briggs had supported but not participated in the attack.

21. Fowler, op cit.

22. Carter Ratcliff, John Singer Sargent, Abbeville Press, New York, 1982, 231 cited in Fowler, op cit.

23. This in fact enabled only a minority of men, predominantly from the middle and upper classes, to qualify.

24. Richardson, op cit at 96.

25. Phillips, op cit at xi.

26. 1913 letter cited in Kate Adie, Fighting on the Home Front: The Legacy of Women in World War One, Hachette UK, 2013.

27. For a graphic first-person account see Constance Lytton, Prisons and Prisoners, William Heinemann, London. 1914; extracted in Eyewitness to History (ed John Carey), Avon Books, New York, 1987 at 423ff.

28. Phillips, opp cit at 141.

29. Phillips, op cit at 176.

30. Phillips, op cit at 186.

31. Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907-14, Chatto and Windus, London, 1987, at 135.

32. Gamboni, op cit at 95.

33. Prisoners Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health Act 1913.

34. As previously noted, Mary Richardson had actually been out of prison on licence under this Act when she carried out her Rokeby Venus attack.

35. Gamboni, op cit at 95-6.

36. Mary Richardson claimed that she was present at this event, though this has been disputed.

37. Mark Bostridge, “1914: Why war caught Britain cold”, BBC History Magazine, January 2014, 22–27. More generally, see the same author's The Fateful Year: England 1914, Penguin, London, 2014.

38. Bostridge, op cit (BBC History) at 23.

39. For differing views on the consistency of her position compare Phillips, op cit at 291ff and June Purvis, Mrs Pankhurst: a Biography, Routledge, London, 2002 at 268ff. Phillips describes it as a “spectacular volte-face”, whereas Purvis argues that it was not an abandonment of feminism, and was explicable as the act of a “patriotic feminist”.

40. Purvis, op cit at 271.

41. Susan and Angela McPherson, Mosley’s Old Suffragette: A Biography of Norah Dacre Fox, Revised edn 2011, at 87; Purvis, op cit.

42. The Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918.

43. Purvis, op cit at 312-4.

44. Phillips, op cit at 303. This situation is reminiscent of the expansion of women’s economic role in the wake of the manpower shortages caused by the London outbreak of the Black Death in 1439: see Caroline Barron, “Medieval queens of industry”, BBC History Magazine, June 2014, 30-33.

45. Phillips, op cit at 303.

46. Phillips, op cit at 299-302.

47. Phillips, op cit at 303.

48. Respected historians differ widely on the relative importance of the various factors. For examples of some differing viewpoints, see Purvis, op cit at 307ff; Phillips, op cit at 304ff; and Martin Pugh, The March of the Women, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2002, at 252ff. For recent books on various aspects of women's suffrage, see Jad Adams, Women and the Vote: A World History, Oxford University Press, 2014; and Jill Liddington, Vanishing for the Vote: Suffrage, citizenship and the Battle for the Census, Manchester University Press, 2014.

© Philip McCouat, 2014, 2015, 2016

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to Home