Exploring Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street, Rainy Day

Experiencing the streets of Paris

If you ever get to see Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street: Rainy Day at the Art Institute of Chicago, the first thing to strike you will probably be its massive size, for it’s almost 10 feet across (276 cm), and almost 7 feet high (212 cm) -- bigger than anything he had ever painted before, and unusual for the times [1]. The main people depicted in the painting are therefore not far short of life-size. It’s a feature, along with our street-level viewpoint, that invites us into feeling that we could simply stroll right into the picture.

In this article, we’ll explore this painting -- which has been described as Caillebotte’s masterpiece [2] – and then go on to consider other aspects of this unusual man’s artistic career, and his rather unexpected major achievements in a wide range of other areas.

In this article, we’ll explore this painting -- which has been described as Caillebotte’s masterpiece [2] – and then go on to consider other aspects of this unusual man’s artistic career, and his rather unexpected major achievements in a wide range of other areas.

What’s happening in the painting?

The painting, set in 1877, depicts a drizzly day in a large and rather featureless Parisian square, now known as the Place de Dublin [3]. This forms part of the district surrounding the Gare Saint-Lazare, an area in which Caillebotte painted a number of other scenes -- such as Le Parc Monceau and Le Pont de l’Europe -- and is not far from where the Caillebotte family lived. In fact, he probably saw this scene on his customary route through the intersection on his way from his home to the cafés frequented by the Impressionists [4]. Other impressionist artists such as Manet and Berthe Morisot also lived and painted there, and Monet was a regular visitor.

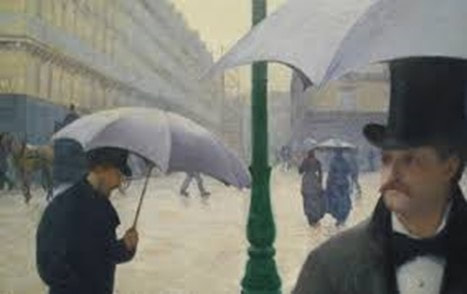

On the square, a scattering of people are crossing in various directions, sheltering under dark-coloured retractable umbrellas [5]. In this pre-automobile age, there is no traffic other than two horse-drawn carriages moving unobtrusively in the background, and large parts of the foreground of the painting are taken up with the wet, unusually large cobblestones of the road surface.

Our eye is drawn principally to the fashionable couple on the right, walking arm-in-arm towards us, sharing an umbrella, on a narrow footpath bordering a building (Fig 2). The man is moustachioed and wears a top hat, bow tie and a frock coat; the woman, her face lightly veiled, wears a fur trimmed outfit and displays a diamond earring. The two have apparently not yet noticed the top-hatted gentleman at far right, walking in the opposite direction – some sort of manoeuvring will shortly be necessary for him to pass.

On the square, a scattering of people are crossing in various directions, sheltering under dark-coloured retractable umbrellas [5]. In this pre-automobile age, there is no traffic other than two horse-drawn carriages moving unobtrusively in the background, and large parts of the foreground of the painting are taken up with the wet, unusually large cobblestones of the road surface.

Our eye is drawn principally to the fashionable couple on the right, walking arm-in-arm towards us, sharing an umbrella, on a narrow footpath bordering a building (Fig 2). The man is moustachioed and wears a top hat, bow tie and a frock coat; the woman, her face lightly veiled, wears a fur trimmed outfit and displays a diamond earring. The two have apparently not yet noticed the top-hatted gentleman at far right, walking in the opposite direction – some sort of manoeuvring will shortly be necessary for him to pass.

Just behind the couple is a prominent green lamppost, which stands on the edge of the footpath; there is, however no sign of curbing or guttering. On the far side of the square there are a number of buildings -- mid-sized, similarly designed and notable for the presence of balconies -- separated by wide streets which radiate away into the misty distance. Shades of the pale yellow that suffuses the painting appear not only on the buildings but also the paving stones and the sky, giving the impression that the sun is trying to break through the clouds [6]. These, together with the dark colour of the pedestrians’ clothes and umbrellas, dominate the colour scheme.

Most of the pedestrians appear to be fashionably-dressed, though there are exceptions -- in the distance behind the foreground couple, we can make out a painter/decorator with his ladder, and a maid standing on the footpath, about to put up (or down) her umbrella (Fig 3). The two people passing each other in the middle of the square in front of the 2nd building from left also appear to be less fashionably dressed [7].

Most of the pedestrians appear to be fashionably-dressed, though there are exceptions -- in the distance behind the foreground couple, we can make out a painter/decorator with his ladder, and a maid standing on the footpath, about to put up (or down) her umbrella (Fig 3). The two people passing each other in the middle of the square in front of the 2nd building from left also appear to be less fashionably dressed [7].

Some commentators have suggested that the subdued colouring, the lack of eye contact between any of the pedestrians, and their generally huddled appearance as they walk across the square, conveys a pervading mood of loneliness and urban alienation. “[The pedestrians} are not out for a stroll, but hurry through empty streets, shielding themselves with their umbrellas not just from the rain, but also, so it seems, from other passers-by” [8]. Similarly, it has been suggested that the “umbrellas….intensify the unsociability of Caillebotte’s chosen urban space; few figures appear to communicate or toe engage another’s gaze, and even the two principal figures seem deliberately to avoid eye contact with the viewer” [9].

To me, these views appear to be overstated. Given that it is a rainy day, one would not expect that people would decide to go strolling bare-headed through the city, or stand gaily chatting to each other on street corners. Their heads-down behaviour simply seems typical of rainy days, and is not necessarily indicative of anything else [10].

To me, these views appear to be overstated. Given that it is a rainy day, one would not expect that people would decide to go strolling bare-headed through the city, or stand gaily chatting to each other on street corners. Their heads-down behaviour simply seems typical of rainy days, and is not necessarily indicative of anything else [10].

Critics’ response to the painting

The painting won favourable reviews when entered in the Third Impressionist Exhibition in 1877. Critic Georges Rivière described Caillebotte as “an intrepid seeker, on whom we pin well-founded hopes” [11], and commented, “Those who have criticised the picture have not dreamed how difficult it was, and what skill was necessary to bring off a canvas of this size” [12].

Emile Zola, who had previously criticised Caillebotte’s work in realist paintings such as The Floorscrapers (Fig 4) as “anti-artistic” and “middle class in its exactitude” now referred to him as “a young painter of the greatest courage and who does not shrink from life-size modern subjects. His Rue de Paris par un Temps de Pluie shows passers-by, especially a gentleman and a lady in the foreground, who are very truthful. When his talent has softened a little more, Mr. Caillebotte will certainly be one of the boldest in the group”.

Emile Zola, who had previously criticised Caillebotte’s work in realist paintings such as The Floorscrapers (Fig 4) as “anti-artistic” and “middle class in its exactitude” now referred to him as “a young painter of the greatest courage and who does not shrink from life-size modern subjects. His Rue de Paris par un Temps de Pluie shows passers-by, especially a gentleman and a lady in the foreground, who are very truthful. When his talent has softened a little more, Mr. Caillebotte will certainly be one of the boldest in the group”.

Like many of the paintings he created, Rainy Day remained in the Caillebotte family, away from public view, until it was purchased in 1955 by prolific art collector Walter P. Chrysler Jr. He later sold it to Wildenstein and Company, a historic art dealership, who, in turn, sold to its present-home The Art Institute of Chicago in 1964.

“Hausmannisation” of Paris

Even given that it is a rainy day, a modern observer used to seeing vehicle-choked city streets will probably be struck by the sparseness of people and traffic depicted here. In Figure 5 you’ll see a present-day photograph of this same square, seen from the same point of view as the painting – the contrast in level of activity and crowding is quite sharp!

To Caillebotte, however, the peaceful scene depicted in the painting would itself have seemed ultra-modern. When he was growing up, this district had been a relatively unsettled hill [13]. But at the time he came to paint it, there had been massive destruction of large areas of medieval Paris, and their replacement by refashioned and extended Paris streets and buildings. In fact, every street and every building that appear in the painting was built during Caillebotte’s lifetime [14]. This sweeping project had been ordered by Napoleon III and carried out under the energetic (some would say overbearing) leadership of Baron Georges Eugene Haussmann.

The rebuilding and expansion were characterised by symmetry and perspective -- wide, straight streets replaced narrow medieval alleys, leading from one square or major building to the next, creating attractive vistas. Large apartment buildings replaced old houses, conforming to height restrictions (generally 4-5 storeys), having prominent balconies running the length of their first and top storeys, and made from uniform dressed creamy yellow limestone (“ashlar” or “Parisian stone”).

All these features we can see in Caillebotte’s painting, and indeed they are still in Paris today. Incidentally, as you can see from Fig 6, the pharmacy which Caillebotte depicted on the corner of the central building is still a pharmacy today, almost 150 years later. And, demonstrating that the “Haussmannisation” project was still not quite complete, there is also scaffolding faintly visible on the building in the distance behind the green lamppost (fig 7).

The rebuilding and expansion were characterised by symmetry and perspective -- wide, straight streets replaced narrow medieval alleys, leading from one square or major building to the next, creating attractive vistas. Large apartment buildings replaced old houses, conforming to height restrictions (generally 4-5 storeys), having prominent balconies running the length of their first and top storeys, and made from uniform dressed creamy yellow limestone (“ashlar” or “Parisian stone”).

All these features we can see in Caillebotte’s painting, and indeed they are still in Paris today. Incidentally, as you can see from Fig 6, the pharmacy which Caillebotte depicted on the corner of the central building is still a pharmacy today, almost 150 years later. And, demonstrating that the “Haussmannisation” project was still not quite complete, there is also scaffolding faintly visible on the building in the distance behind the green lamppost (fig 7).

Style and composition

Caillebotte is often described as an Impressionist, and he indeed did some paintings in a typical Impressionist style (see, for example, Fig 10). But most of his works, including Rainy Day, are done in a much more realist style, with an emphasis on structure and composition, rather than the light effects, colours and unfinished quality that characterise what we now regard as typically Impressionist.

Caillebotte shared a keen interest in photography with his brother Martial, for whom it was a major activity, and there are suggestions of photographic influences in Rainy Day. So, for example, the top hatted man at far right is virtually cut in two by the edge of the painting, creating a snapshot effect, similar to the cut-off figures often painted by Caillebotte’s friend Edgar Degas [15]. Various features of the painting are also (deliberately) partly obscured, as would happen incidentally in the “frozen moment” captured by a snapshot [16] -- the ubiquitous umbrellas block out parts of the horse-drawn carriages and, in one case, completely obscure the torso of a pedestrian, leaving just his legs to our view (Fig 7). The unusual width of the scene has a similarity to a wide-angle lens [17].

The sharp contrast between the sharpness of the foreground figures and the more blurred buildings in the background is also reminiscent of a photograph. In this connection, there are interesting parallels with a photograph taken by Martial of Caillebotte himself, standing in a vast sparsely-populated Paris square in 1892 (Fig 7A).

Caillebotte shared a keen interest in photography with his brother Martial, for whom it was a major activity, and there are suggestions of photographic influences in Rainy Day. So, for example, the top hatted man at far right is virtually cut in two by the edge of the painting, creating a snapshot effect, similar to the cut-off figures often painted by Caillebotte’s friend Edgar Degas [15]. Various features of the painting are also (deliberately) partly obscured, as would happen incidentally in the “frozen moment” captured by a snapshot [16] -- the ubiquitous umbrellas block out parts of the horse-drawn carriages and, in one case, completely obscure the torso of a pedestrian, leaving just his legs to our view (Fig 7). The unusual width of the scene has a similarity to a wide-angle lens [17].

The sharp contrast between the sharpness of the foreground figures and the more blurred buildings in the background is also reminiscent of a photograph. In this connection, there are interesting parallels with a photograph taken by Martial of Caillebotte himself, standing in a vast sparsely-populated Paris square in 1892 (Fig 7A).

Even if the painting is in many ways like a snapshot, its composition was perfectly planned and deliberate. Caillebotte did many detailed preliminary sketches of the pedestrians, exhibiting considerable changes and experimentation to achieve his desired effect [18].Careful planning, so important in a large painting such as this, is also evident in the way that the scene is divided into quadrants, with the vertical green lamppost defining the right and left sides. The upper and lower parts of the painting are divided by the roughly horizontal base line of the buildings, and by the positioning of most of the distant pedestrians (who seem unrealistically small, probably as part of a deliberate attempt to accentuate the size of the square). This horizontal also corresponds roughly with the viewer’s eye-line.

The main action, as we have seen, is at lower right. The lower left is dominated by the paving stones and the mid-distance pedestrians. The upper left is dominated by the geometrical lines of the buildings, and the upper right is largely obstructed by the umbrellas of the strolling couple.

Caillebotte has sought to counter the broad horizontal sweep of the square with the strong verticals of the buildings, the lamppost (and its reflection on the wet footpath) and even the shaft of the man’s umbrella. He also has the couple looking sharply to the left, which helps to unify a composition which might otherwise feel unbalanced.

The main action, as we have seen, is at lower right. The lower left is dominated by the paving stones and the mid-distance pedestrians. The upper left is dominated by the geometrical lines of the buildings, and the upper right is largely obstructed by the umbrellas of the strolling couple.

Caillebotte has sought to counter the broad horizontal sweep of the square with the strong verticals of the buildings, the lamppost (and its reflection on the wet footpath) and even the shaft of the man’s umbrella. He also has the couple looking sharply to the left, which helps to unify a composition which might otherwise feel unbalanced.

Collector and champion of the Impressionists

Caillebotte’s career as a painter was at its highest level for only a few years from 1875 onwards and, as we shall see, it ceased being the main focus of his creative life when overtaken by other passionate interests in boating, philately and gardening [19] -- not to mention his crucial role in championing the Impressionist cause over an extended period during which it was largely derided or ignored.

Kirk Varnedoe, noting that the success of Impressionism did not arrive by default, said, “it required …hard work on the part of several individuals, among whom Caillebotte was one of the most dedicated. He haggled and negotiated to keep the group together through periods of fractious disagreement, and when he had to, he rented the exhibition space, paid for the advertising, bought frames and hung the pictures… Caillebotte further fuelled the movement by buying paintings from his needy colleagues. Yet, more than just a source of charity, he was also a collector with uncannily astute judgement” [20].

Caillebotte rarely turned down a request for an advance, often helped out on rent, and his numerous purchases of paintings and social connections were often lifesavers for his struggling colleagues. He became a close friend of Impressionists such as Monet, and was particularly close to Renoir, who regarded him as the first patron of Impressionism [21]. They painted each other’s wives, and Caillebotte included Renoir’s Dance at the Moulin de la Galette (which he’d bought at the Third Impressionist Exhibition) in one of his self-portraits. Caillebotte also named Renoir executor of his will and was godfather to Renoir’s first son.

Caillebotte’s role in supporting the Impressionists was crowned by the far-sighted bequest of his extraordinary collection to the State. We shall discuss this hugely controversial bequest further below (under the heading “Gift to the Nation”), but first we must explore some of his other extraordinary interests.

Kirk Varnedoe, noting that the success of Impressionism did not arrive by default, said, “it required …hard work on the part of several individuals, among whom Caillebotte was one of the most dedicated. He haggled and negotiated to keep the group together through periods of fractious disagreement, and when he had to, he rented the exhibition space, paid for the advertising, bought frames and hung the pictures… Caillebotte further fuelled the movement by buying paintings from his needy colleagues. Yet, more than just a source of charity, he was also a collector with uncannily astute judgement” [20].

Caillebotte rarely turned down a request for an advance, often helped out on rent, and his numerous purchases of paintings and social connections were often lifesavers for his struggling colleagues. He became a close friend of Impressionists such as Monet, and was particularly close to Renoir, who regarded him as the first patron of Impressionism [21]. They painted each other’s wives, and Caillebotte included Renoir’s Dance at the Moulin de la Galette (which he’d bought at the Third Impressionist Exhibition) in one of his self-portraits. Caillebotte also named Renoir executor of his will and was godfather to Renoir’s first son.

Caillebotte’s role in supporting the Impressionists was crowned by the far-sighted bequest of his extraordinary collection to the State. We shall discuss this hugely controversial bequest further below (under the heading “Gift to the Nation”), but first we must explore some of his other extraordinary interests.

A man of many talents: boating, philately and horticulture

Early in his adult life, Caillebotte inherited a fortune from his father, and was never under financial pressure to work for a living, or to sell his paintings. But, in addition to his artistic career and interests, he showed a tremendous ability and determination to excel in a large number of diverse areas -- achieving international eminence in the fields of boat designing and philately, and becoming a respected authority on garden design and horticulture. By all accounts, he was a realistic, energetic and highly organised person who, at the same time, was modest about his achievements.

In 1876, Caillebotte joined the Cercle de la Voile de Paris (CVP), a small club for sailing enthusiasts, which became “one of the most prestigious and active clubs” of the late nineteenth century. As Samuel Raybone has recorded, Caillebotte purchased his first boat in 1878 and would own thirteen more before he died. In the late 1870s he began to race seriously, becoming one of the most successful yachtsmen in France. He became a founding subscriber of Le Yacht, the first French review on boating; he was instrumental in the organization and institutionalization of the sport; designed the world’s first truly international handicapping system; financed a dedicated, modern, and high quality racing yacht yard; invented a new class of sailing vessel (based on sail area); and designed twenty-five boats which revolutionized French sailing with their thoroughly modern, and often experimental, designs [22]. Boating also became a recurring theme in his paintings.

In 1876, Caillebotte joined the Cercle de la Voile de Paris (CVP), a small club for sailing enthusiasts, which became “one of the most prestigious and active clubs” of the late nineteenth century. As Samuel Raybone has recorded, Caillebotte purchased his first boat in 1878 and would own thirteen more before he died. In the late 1870s he began to race seriously, becoming one of the most successful yachtsmen in France. He became a founding subscriber of Le Yacht, the first French review on boating; he was instrumental in the organization and institutionalization of the sport; designed the world’s first truly international handicapping system; financed a dedicated, modern, and high quality racing yacht yard; invented a new class of sailing vessel (based on sail area); and designed twenty-five boats which revolutionized French sailing with their thoroughly modern, and often experimental, designs [22]. Boating also became a recurring theme in his paintings.

Caillebotte also took up collecting stamps with his brother Martial round 1878, and, aided by their financial clout, the brothers quite rapidly became leading international figures in the world of philately, combining their forces to systematically build up a huge collection of exceptional quality. The brothers pioneered the study of post marks, published an extensive study of Mexican stamps, contributed greatly to the study of Australian stamps, and were posthumously honoured in 1921 as “Fathers of Philately” in the Roll of Distinguished Philatelists of the Philatelic Congress of Great Britain. Their philatelic activities came to an end after Martial got married, and their 50-volume collection was eventually sold for £5,000, a staggering figure at the time. Large parts of it were incorporated into the almost legendary collection of Thomas Tapling, and later bequeathed to the British Museum [23].

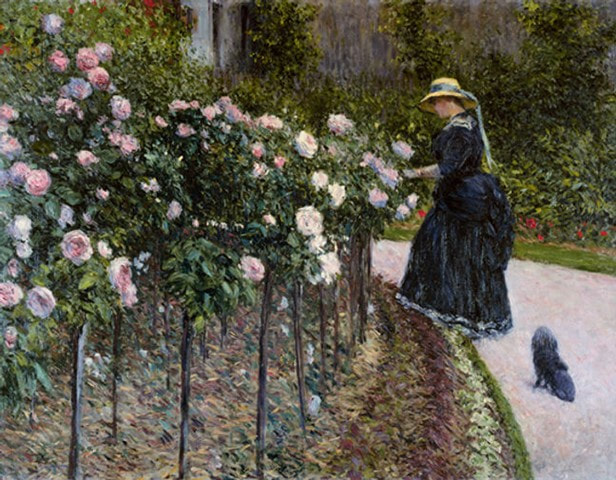

Horticulture became yet another passionate interest. In 1881, Caillebotte left the family estate at Yerres and bought a smaller property in Petit Gennevilliers, quite close to Monet’s famous house at Giverny. As with boating, Caillebotte threw himself into horticulture, designing a huge garden which he and his helpers created and maintained, building a studio and a massive greenhouse, acquiring specialist knowledge on exotic plants such as orchids and giving advice on horticultural matters to Monet [24].

Many of his later paintings became dominated by flowers, such as his study of gardeners watering new plants in a corner of his walled estate (Fig 9), and his depiction, in Impressionist style, of his long-term partner, Charlotte Berthier (aka Ann-Marie Hagen) and her dog in an established part of the garden (Fig 10) [25]. Sadly, unlike Monet’s Giverny, Caillebotte’s garden became a victim of creeping industrialisation and bombing in World War II, and not a trace of it survives.

Horticulture became yet another passionate interest. In 1881, Caillebotte left the family estate at Yerres and bought a smaller property in Petit Gennevilliers, quite close to Monet’s famous house at Giverny. As with boating, Caillebotte threw himself into horticulture, designing a huge garden which he and his helpers created and maintained, building a studio and a massive greenhouse, acquiring specialist knowledge on exotic plants such as orchids and giving advice on horticultural matters to Monet [24].

Many of his later paintings became dominated by flowers, such as his study of gardeners watering new plants in a corner of his walled estate (Fig 9), and his depiction, in Impressionist style, of his long-term partner, Charlotte Berthier (aka Ann-Marie Hagen) and her dog in an established part of the garden (Fig 10) [25]. Sadly, unlike Monet’s Giverny, Caillebotte’s garden became a victim of creeping industrialisation and bombing in World War II, and not a trace of it survives.

Gift to the Nation

Caillebotte died of a stroke in 1894 as he tended his beloved plants at the garden in Petit-Gennevillers. He was only 45. As part of his estate, he left his collection of 68 works, mostly Impressionist, to the French State. They included works by Pissarro, Degas, Cézanne, Sisley, Morisot, Monet, Renoir, Millet and Manet.

Surprising as it may seem today, the Caillebotte Bequest was initially refused by the State. There were various reasons for their reticence. The State was accustomed to itself selecting and purchasing works for the national collection, not having outsiders decide for them what should be included, especially as Impressionists had never ranked highly in any event in their list of priorities [26].

The authorities were also concerned by Caillebotte’s insistence that all 68 works must be accepted in full, and that they be given a dedicated space in a prestigious museum’s collection. Added to this, the authorities felt that acceptance of the Bequest as a whole would necessarily violate their official policy of exhibiting no more than three works from any individual artist [27].

Almost 20 years later, after strenuous and protracted negotiations jointly conducted by Renoir, as executor of Caillebotte’s estate, and Martial, and a growing realisation by the government that they must be seen to be moving forwards, a compromise was finally reached. Forty of the works were accepted and were later installed in the Musée du Luxembourg in 1897; they are now among the most famous works in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

The government was given two more opportunities to acquire the remaining 28 works, but refused. Decades later, presumably inspired by the growing popularity (and value) of Impressionist works, the government changed its mind and made a legal claim for those works, but it was far too late. The estate rejected the government’s claim outright, and proceeded to put the paintings on the open market, where they were sold mainly to private collectors, such as Albert Barnes [28].

In the Bequest, Caillebotte had modestly refrained from including any works which he himself had painted. Subsequently, this injustice was corrected when the indefatigable Renoir was able to negotiate for The Floor Scrapers (Fig 4) to be added.

Surprising as it may seem today, the Caillebotte Bequest was initially refused by the State. There were various reasons for their reticence. The State was accustomed to itself selecting and purchasing works for the national collection, not having outsiders decide for them what should be included, especially as Impressionists had never ranked highly in any event in their list of priorities [26].

The authorities were also concerned by Caillebotte’s insistence that all 68 works must be accepted in full, and that they be given a dedicated space in a prestigious museum’s collection. Added to this, the authorities felt that acceptance of the Bequest as a whole would necessarily violate their official policy of exhibiting no more than three works from any individual artist [27].

Almost 20 years later, after strenuous and protracted negotiations jointly conducted by Renoir, as executor of Caillebotte’s estate, and Martial, and a growing realisation by the government that they must be seen to be moving forwards, a compromise was finally reached. Forty of the works were accepted and were later installed in the Musée du Luxembourg in 1897; they are now among the most famous works in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

The government was given two more opportunities to acquire the remaining 28 works, but refused. Decades later, presumably inspired by the growing popularity (and value) of Impressionist works, the government changed its mind and made a legal claim for those works, but it was far too late. The estate rejected the government’s claim outright, and proceeded to put the paintings on the open market, where they were sold mainly to private collectors, such as Albert Barnes [28].

In the Bequest, Caillebotte had modestly refrained from including any works which he himself had painted. Subsequently, this injustice was corrected when the indefatigable Renoir was able to negotiate for The Floor Scrapers (Fig 4) to be added.

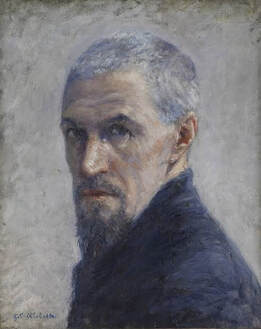

Conclusion: stepping out from the shadows

Gustave Caillebotte enjoyed considerable critical success during his lifetime, but he was not a typical example of a famous Impressionist artist. So, for example. he never struggled financially; and painting did not dominate his whole life -- he had other interests in which he excelled, which to his way of thinking, transcended his art. Nor did he seek personal publicity or aggrandisement. He spent a large amount of time (and money) helping out other artists. Many of his works stayed in the family, rather than being sold or being acquired by public institutions. He died young. And, not least, most of his works are not overly impressionist!

Caillebotte himself was very modest about his achievements as a painter. Jean Renoir reports him as saying, “I try to paint honestly, hoping that someday my works will be good enough to hang in the ante-chamber of the living room where the Renoirs and Cézannes are hung” [29].

Caillebotte himself was very modest about his achievements as a painter. Jean Renoir reports him as saying, “I try to paint honestly, hoping that someday my works will be good enough to hang in the ante-chamber of the living room where the Renoirs and Cézannes are hung” [29].

|

After his death, his reputation fell – he was too difficult to categorise, too self-effacing, too overshadowed by the eventual glittering success of Impressionists such as Monet and Renoir.

The 1980s, however, saw the beginnings of a revival of interest [30] and subsequently there has also been a fuller understanding of his other major achievements [31]. Today, Caillebotte has finally stepped out of the shadows of others and we are able to treat him on his own merits, recognising his own unique set of talents ■ |

© Philip McCouat, 2023. first published March 2023

We welcome your comments on this article

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, "Exploring Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street, Rainy Day”, Journal of Art in Society, March 2023.

Return to HOME

We welcome your comments on this article

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, "Exploring Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street, Rainy Day”, Journal of Art in Society, March 2023.

Return to HOME

End Notes

[1] The name “Caillebotte” is pronounced like “Kieya-bot”, though it is frequently mispronounced as “Kalli-bot”

[2] Kirk Varnedoe, Gustave Caillebotte, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1987, at 88

[3] At the time of the painting, it was called the Carrefour de Moscou

[4] Gloria Groom and Kelly Keegan, “Paris Street; Rainy Day”, in Caillebotte: Paintings and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago, at 3

[5] The retractable style had just been newly invented: see Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, “Under the umbrella, loneliness”, in What Great Paintings Say, Vol 2, Taschen, London, 2003, at 405. Recent conservation and cleaning reveals that the canopies of the umbrellas actually have lavender tones: Groom, op cit at 9

[6] Groom, op cit at 9

[7] Before the recent conservation of the painting, these people were generally interpreted as a couple walking together: Groom, op cit

[8] Hagen, op cit at 404

[9] Julia Sagraves, cited in Michael Fried, “Caillebotte’s Impressionism”, Representations, No 66 (Spring 1999) at 26

[10] See also Fried, op cit at 26ff

[11] Cited in Hagen, op cit at 402

[12] Cited in Groom, op cit at 2

[13] Groom, op cit

[14] Varnedoe, op cit at 88

[15] See our article at https://www.artinsociety.com/pt-3-photographic-effects.html

[16] Groom, op cit at 1

[17] Groom suggests, on the basis of physical evidence, that Caillebotte may have used a camera lucida as an aid to composition in the painting (op cit at 6,7; see also Kirk Varnedoe, op cit at 20ff, 187

[18] Groom, op cit at 10

[19] Fried, op cit at 2

[20] Kirk Varnedoe, “Odd Man In”, in Ann Distel et al, Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, Abbeville Press, New York, 1995, at 13

[21] Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists, Chatto and Windus, London, 2006, at 145

[22] Samuel Raybone, “Gustave Caillebotte’s Interiors: Working Between Leisure and Labor”, November 2018, https://nonsite.org/article/gustave-caillebottes-interiors. For more on Caillebotte’s sailing-related activities see Daniel Charles, “Caillebotte and Boating,” in Gustave Caillebotte, Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark et al., exh. cat. Copenhagen: Ordrupgaard; Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2008

[23] Raybone, op cit; for more on Caillebotte’s philatelic career, see R. D. Beech, “Note on Caillebotte as a Philatelist,” in Anne Distel, op cit at 206

[24] Anne Foster, “Caillebotte in his Garden”, La Gazette Drouot, May 2019 https://www.gazette-drouot.com/en/article/caillebotte-in-his-garden/6931; Distel, op cit at 22

[25] Charlotte was regarded as his wife by the Renoirs and presumably others (Jean Renoir, Renoir my Father (English translation), Fontana, London, 1965 at 250), though Martial’s wife Marie rejected Gustave when she learned of this slightly irregular arrangement. In his will, Caillebotte left “the little house that I own in Petit Gennevilliers” to Charlotte, along with a sizeable annuity

[26] At that time, there had only been formal museum acquisitions of two paintings associated with Impressionism

[27] John P Walsh, The “tricky business” of the Caillebotte Bequest, https://johnpwalshblog.com/2013/04/12/the-tricky-business-of-the-caillebotte-bequest/

[28] See our article at https://www.artinsociety.com/strange-encounters-the-collector-the-artist-and-the-philosopher.html

[29] Renoir, op cit at 250

[30] Initiated by art historians such as Kirk Varnedoe: see note (2)

[31] Notably, by Samuel Raybone, in Gustave Caillebotte as Worker, Collector, Painter. Bloomsbury, 2019

© Philip McCouat, 2023. First published March 2023.

Return to HOME

[2] Kirk Varnedoe, Gustave Caillebotte, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1987, at 88

[3] At the time of the painting, it was called the Carrefour de Moscou

[4] Gloria Groom and Kelly Keegan, “Paris Street; Rainy Day”, in Caillebotte: Paintings and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago, at 3

[5] The retractable style had just been newly invented: see Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, “Under the umbrella, loneliness”, in What Great Paintings Say, Vol 2, Taschen, London, 2003, at 405. Recent conservation and cleaning reveals that the canopies of the umbrellas actually have lavender tones: Groom, op cit at 9

[6] Groom, op cit at 9

[7] Before the recent conservation of the painting, these people were generally interpreted as a couple walking together: Groom, op cit

[8] Hagen, op cit at 404

[9] Julia Sagraves, cited in Michael Fried, “Caillebotte’s Impressionism”, Representations, No 66 (Spring 1999) at 26

[10] See also Fried, op cit at 26ff

[11] Cited in Hagen, op cit at 402

[12] Cited in Groom, op cit at 2

[13] Groom, op cit

[14] Varnedoe, op cit at 88

[15] See our article at https://www.artinsociety.com/pt-3-photographic-effects.html

[16] Groom, op cit at 1

[17] Groom suggests, on the basis of physical evidence, that Caillebotte may have used a camera lucida as an aid to composition in the painting (op cit at 6,7; see also Kirk Varnedoe, op cit at 20ff, 187

[18] Groom, op cit at 10

[19] Fried, op cit at 2

[20] Kirk Varnedoe, “Odd Man In”, in Ann Distel et al, Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, Abbeville Press, New York, 1995, at 13

[21] Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists, Chatto and Windus, London, 2006, at 145

[22] Samuel Raybone, “Gustave Caillebotte’s Interiors: Working Between Leisure and Labor”, November 2018, https://nonsite.org/article/gustave-caillebottes-interiors. For more on Caillebotte’s sailing-related activities see Daniel Charles, “Caillebotte and Boating,” in Gustave Caillebotte, Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark et al., exh. cat. Copenhagen: Ordrupgaard; Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2008

[23] Raybone, op cit; for more on Caillebotte’s philatelic career, see R. D. Beech, “Note on Caillebotte as a Philatelist,” in Anne Distel, op cit at 206

[24] Anne Foster, “Caillebotte in his Garden”, La Gazette Drouot, May 2019 https://www.gazette-drouot.com/en/article/caillebotte-in-his-garden/6931; Distel, op cit at 22

[25] Charlotte was regarded as his wife by the Renoirs and presumably others (Jean Renoir, Renoir my Father (English translation), Fontana, London, 1965 at 250), though Martial’s wife Marie rejected Gustave when she learned of this slightly irregular arrangement. In his will, Caillebotte left “the little house that I own in Petit Gennevilliers” to Charlotte, along with a sizeable annuity

[26] At that time, there had only been formal museum acquisitions of two paintings associated with Impressionism

[27] John P Walsh, The “tricky business” of the Caillebotte Bequest, https://johnpwalshblog.com/2013/04/12/the-tricky-business-of-the-caillebotte-bequest/

[28] See our article at https://www.artinsociety.com/strange-encounters-the-collector-the-artist-and-the-philosopher.html

[29] Renoir, op cit at 250

[30] Initiated by art historians such as Kirk Varnedoe: see note (2)

[31] Notably, by Samuel Raybone, in Gustave Caillebotte as Worker, Collector, Painter. Bloomsbury, 2019

© Philip McCouat, 2023. First published March 2023.

Return to HOME