Bernardo Bellotto and the reconstruction of Warsaw

How a hidden cache of 18th century artworks provided a blueprint for the resurrection of a destroyed city

1. Introduction: capturing the past

When World War II ended in Europe in May 1945 [1], the Polish capital Warsaw was in ruins. More than 90% of its buildings had been damaged or destroyed over the course of the hostilities.

Poland’s new communist government embarked on a massive program to reconstruct the city. For the historic centre they decided not to create a new modern precinct, or even to restore it to as it had been immediately before the War. Instead, they decided to reconstruct it according to how it had looked in its “golden age”. Given that this was almost 200 years before, this posed an obvious question – how could anyone really know what it looked like in those pre-photographic times? Fortunately, however, there was a ready answer -- the fortuitous, almost miraculous, survival of a series of meticulously precise paintings of the city which had been created by the artist Bernardo Bellotto, right at the height of the golden age.

Creating a modern city plan on the basis of some centuries-old paintings might seem to be a quixotic, even bizarre, undertaking. To understand it, and to evaluate its success, we need to go back a step, to the tragic circumstances of Poland’s involvement in the War.

Poland’s new communist government embarked on a massive program to reconstruct the city. For the historic centre they decided not to create a new modern precinct, or even to restore it to as it had been immediately before the War. Instead, they decided to reconstruct it according to how it had looked in its “golden age”. Given that this was almost 200 years before, this posed an obvious question – how could anyone really know what it looked like in those pre-photographic times? Fortunately, however, there was a ready answer -- the fortuitous, almost miraculous, survival of a series of meticulously precise paintings of the city which had been created by the artist Bernardo Bellotto, right at the height of the golden age.

Creating a modern city plan on the basis of some centuries-old paintings might seem to be a quixotic, even bizarre, undertaking. To understand it, and to evaluate its success, we need to go back a step, to the tragic circumstances of Poland’s involvement in the War.

2. The attack on Poles, their buildings and their culture

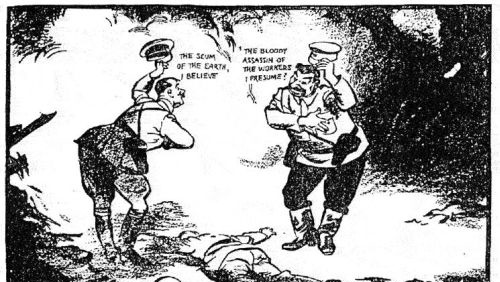

In September 1939, in an act that precipitated the outbreak of World War II [2], Poland was attacked in a Blitzkrieg attack from the west by Nazi Germany. A few weeks later, it was attacked from the east by the Soviet Union. Under the 1939 German/Soviet Non-Aggression Pact [3], the two unlikely alllies proceeded to partition Poland between themselves, with the Germans taking the west, occupied by some 20 million Poles, and the Soviets taking the east, which had about 12 million. With that partition, Poland ceased to exist as a separate country in its own right.

It was particularly unfortunate for Poland that both Germany and the Soviet Union had their own particular interest in suppressing most forms of Polish culture. The Soviets were deeply suspicious of a wide range of Poles whom they considered to be hostile to the Soviet Union and to communism – army officers, policemen, priests, prison guards, landowners and the intelligentsia. Over 20,000 of these people were rounded up and shot [4]. Over the following months, hundreds of thousands – perhaps as many as a million – of other target groups were identified, rounded up and deported to Siberia or the hard-labour camps of the Gulag. These groups ranged from teachers, merchants and local politicians to (rather oddly) Esperantists, postmasters and philatelists [5]. These activities continued until the Soviets were driven out by their former ally Germany in 1941.

The Nazis, for their part, were pursuing an equally devastating policy, euphemistically known as the “Extraordinary Pacification Operation”. Hitler had originally urged his forces to “act brutally…be harsh and relentless”, and had encouraged them to “kill without pity or mercy all men, women and children of Polish descent or language” in the coming “invasion and extermination of Poland” [6]. This policy was implemented with utmost vigour. Initially, this involved arresting about 30,000 Polish academics, intellectuals, teachers and writers, with most being sent to concentration camps, and some 6,000 being executed. Some 87,000 Poles and Jews (most classed as sub-human degenerates) were forcibly deported from their homes to make “living space” for ethnic Germans. About a million others were deported to Germany to join labour gangs. About 400,000 Jews were crowded into a high-walled Ghetto with an area of only 3.4 sq kms, with many being "deported" for execution, Many thousands were murdered in April 1943 after the Jewish Ghetto revolt and again in the reprisals for the Warsaw uprising in August 1944 (which had beens the largest single military effort taken by any European resistance movement during the War).

Overall, over the course of the War, it is estimated that several million Poles were killed, including one-third of Catholic priests and doctors, and half of Polish lawyers; about half a million citizens were crippled for life, and a million children orphaned [7]. Another half a million Polish citizens, including most of its political and military leadership, and many leading writers and artists, became scattered round the world, never to return.

The Nazis confiscated all Jewish property, all Polish private property and Polish state enterprises [8]. German was declared to be the official language, and Polish people’s access to education, art and science was radically curtailed. Polish youths were denied the right to secondary or tertiary education, being restricted to vocational schools. Many centres of culture were closed, including libraries, theatres and concert halls. Even the playing of the works of Poland’s most famous composer, Chopin, was forbidden. Religious practice was generally hindered.

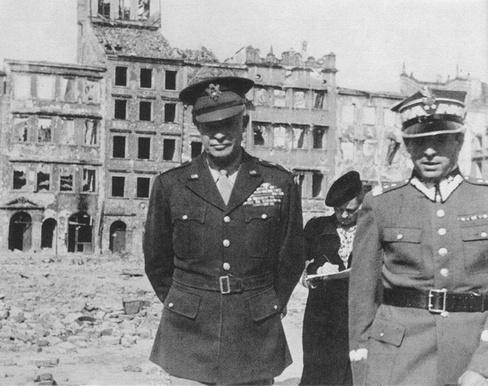

Physical damage to buildings and property was immense. This differed from that in much of Western Europe because of the extent to which the destruction of buildings of cultural and historic interest was deliberate and systematic, rather than being incidental to the course of war action [9]. It is estimated that about 40% of these types of building were destroyed in the country as a whole [10], with all of the historic town centre of Warsaw being virtually destroyed, 782/987 of its historic monuments disappearing and 141 being partly damaged [11]. Overall, Allied Commander General Eisenhower concluded, “I have seen many cities destroyed, but nowhere have I been faced with such destruction” (Fig 2).

The Nazis, for their part, were pursuing an equally devastating policy, euphemistically known as the “Extraordinary Pacification Operation”. Hitler had originally urged his forces to “act brutally…be harsh and relentless”, and had encouraged them to “kill without pity or mercy all men, women and children of Polish descent or language” in the coming “invasion and extermination of Poland” [6]. This policy was implemented with utmost vigour. Initially, this involved arresting about 30,000 Polish academics, intellectuals, teachers and writers, with most being sent to concentration camps, and some 6,000 being executed. Some 87,000 Poles and Jews (most classed as sub-human degenerates) were forcibly deported from their homes to make “living space” for ethnic Germans. About a million others were deported to Germany to join labour gangs. About 400,000 Jews were crowded into a high-walled Ghetto with an area of only 3.4 sq kms, with many being "deported" for execution, Many thousands were murdered in April 1943 after the Jewish Ghetto revolt and again in the reprisals for the Warsaw uprising in August 1944 (which had beens the largest single military effort taken by any European resistance movement during the War).

Overall, over the course of the War, it is estimated that several million Poles were killed, including one-third of Catholic priests and doctors, and half of Polish lawyers; about half a million citizens were crippled for life, and a million children orphaned [7]. Another half a million Polish citizens, including most of its political and military leadership, and many leading writers and artists, became scattered round the world, never to return.

The Nazis confiscated all Jewish property, all Polish private property and Polish state enterprises [8]. German was declared to be the official language, and Polish people’s access to education, art and science was radically curtailed. Polish youths were denied the right to secondary or tertiary education, being restricted to vocational schools. Many centres of culture were closed, including libraries, theatres and concert halls. Even the playing of the works of Poland’s most famous composer, Chopin, was forbidden. Religious practice was generally hindered.

Physical damage to buildings and property was immense. This differed from that in much of Western Europe because of the extent to which the destruction of buildings of cultural and historic interest was deliberate and systematic, rather than being incidental to the course of war action [9]. It is estimated that about 40% of these types of building were destroyed in the country as a whole [10], with all of the historic town centre of Warsaw being virtually destroyed, 782/987 of its historic monuments disappearing and 141 being partly damaged [11]. Overall, Allied Commander General Eisenhower concluded, “I have seen many cities destroyed, but nowhere have I been faced with such destruction” (Fig 2).

Artworks, too, were destroyed or looted on a massive scale. While being scathing of the standard of Polish art culture, the Nazis retained the right to appropriate for “safeguarding” any artworks as they saw fit. In deciding what to take, the Nazis were guided by advice from a “phalanx of distinguished German art historians”, some of whom, it appeared, had a strong belief in the “Germanic origins of anything of value in Poland” [12]. This greatly accelerated a trend which had been evident for many years. As Lynn Nicholas points out, “The continual need to rescue the evidence of ancient history and culture from the destructive power of the Partitioning Powers (Austria, Prussia and Russia) had kept Polish collections in a state of flux for nearly two centuries. Objects had repeatedly been carried off to Berlin or Russia, or been evacuated by their owners to Paris or Switzerland” [13].

By the end of the War, Poland had lost its independence, almost half of its territory and 30% of its population. The fanatical ruthlessness with which the Nazis destroyed Warsaw and attacked its people and culture is scarcely believable, even for modern observers who have become used to large scale destruction. Overall, it is a grim irony [14] that although Poland had been a member of the victorious Allies, and the need for its protection had been a trigger for the War itself, it was actually one of the War’s biggest losers.

By the end of the War, Poland had lost its independence, almost half of its territory and 30% of its population. The fanatical ruthlessness with which the Nazis destroyed Warsaw and attacked its people and culture is scarcely believable, even for modern observers who have become used to large scale destruction. Overall, it is a grim irony [14] that although Poland had been a member of the victorious Allies, and the need for its protection had been a trigger for the War itself, it was actually one of the War’s biggest losers.

3. Why and how Warsaw was reconstructed

n 1945, with the eventual expulsion of the Nazis by the Soviet advance, the postwar “Polish People’s Republic” acquired a communist-controlled government and effectively became part of the Soviet sphere of influence.

The new government ultimately decided that, despite the level of destruction, Warsaw should be restored as the capital, as a matter of “national honour”. The rebuilding and modernising project which was eventually carried out was largely in the grey Soviet block style. However, for the historic old town part of the city, after considerable agonising, the government committed itself to an ambitious “reconstruction” of what the town used to look like during its so-called “golden age” in the 1760s and 1770s. During that period, Poland had been undergoing a considerable cultural revival and geographic expansion – a sort of Polish Enlightenment – and was free of what the planners regarded as the later excesses of untrammelled capitalism [15].

The general idea was to hand down “to future generations at least the exact shape of these monuments, even if it were not authentic, because it was alive in human memory and accessible through historical sources” [16]. To its detractors, this approach carried the risk of ending up with a sort of tokenistic “toy town” or theme park. As a partial answer to this, the restorers determined not just to create a theatrical likeness, but to try to ensure that the rebuilding met scientific criteria and was credible to the public [17].

The new government ultimately decided that, despite the level of destruction, Warsaw should be restored as the capital, as a matter of “national honour”. The rebuilding and modernising project which was eventually carried out was largely in the grey Soviet block style. However, for the historic old town part of the city, after considerable agonising, the government committed itself to an ambitious “reconstruction” of what the town used to look like during its so-called “golden age” in the 1760s and 1770s. During that period, Poland had been undergoing a considerable cultural revival and geographic expansion – a sort of Polish Enlightenment – and was free of what the planners regarded as the later excesses of untrammelled capitalism [15].

The general idea was to hand down “to future generations at least the exact shape of these monuments, even if it were not authentic, because it was alive in human memory and accessible through historical sources” [16]. To its detractors, this approach carried the risk of ending up with a sort of tokenistic “toy town” or theme park. As a partial answer to this, the restorers determined not just to create a theatrical likeness, but to try to ensure that the rebuilding met scientific criteria and was credible to the public [17].

How though was this to be achieved, given the general lack of documentation of how things looked so long ago [18]? The answer lay in an extraordinary collection of over 20 panoramic paintings which had been created by the eighteenth century Venetian artist, Bernardo Bellotto. These paintings provided a vivid view of Warsaw at the critical time, by someone who was actually there. Not only that, but Bellotto used the “camera obscura” technique to ensure an almost photographic accuracy [19], and was famous for his obsessional attention to architectural detail and perspective (Fig 4).

Bellotto’s paintings were therefore used extensively by the Warsaw Preservation Department (WPD) in the reconstruction of the old city and other areas such as the Royal Way. Many buildings had long since disappeared, so Bellotto’s paintings were almost the only source. So great is this debt that Majewski has commented that the present Royal Way could even justifiably be named after the artist [20]. Indeed, many locations in the city now actually display reproductions of the Bellotto painting on which their reconstruction was based (Fig 4A).

The reconstruction of the Church of the Blessed Sacrament provides a good example of Bellotto’s crucial role. His 1778 painting of the church is shown in Fig 5. How it looked after its destruction during the War is shown in Fig 6, and the reconstructed Church as it appears today, closely following Bellotto’s depiction, is shown in Fig 7.

4. Bellotto / canaletto and his paintings

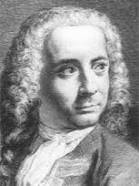

So who was this Bernardo Bellotto? He was born in Venice in 1721, the nephew of the famous painter Giovanni Antonio Canal, aka “Canaletto”. Bellotto followed in his uncle’s steps by specialising in accurate and detailed city vistas (vedute). In later years, he even confusingly adopted Canaletto’s name [21]. He travelled widely through Europe, typically obtaining major commissions for cycles of city views, culminating in his 1768 appointment as the court painter for Poland’s last king, Stanislaw August Poniatowski. It was here that he produced the panoramic city views of Warsaw which would later become so important in the reconstruction.

That these paintings survived at all through the War was a matter of luck. Before the War they had been housed in the Royal Castle. Because of the risk of bombing, they were evacuated to the National Museum [22]. After the Soviet invasion in 1939, they were requisitioned with the aim of “protecting the artworks which are in the occupied territories of former Poland”. In 1940, however they were confiscated by the Germans, taken to Cracow, and then to Muhrau Castle in the Legnica region of Lower Silesia. Their whereabouts at this time was of course unknown to the Polish, and their continued absence caused considerable fears that they had been irretrievably lost or destroyed. Towards the end of the War, as the allied troops were advancing, the Germans transferred the paintings to Callenberg Castle (Fig 9), the summer residence of the Dukes of Coburg. It was here that they were finally found by the American Art Protection Service (the Monuments Men) and taken to the Central Collecting Point at Munich. The Polish authorities were able to reclaim them in 1946 and they were returned, virtually unscathed, to the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw.

5. Art, architecture and “authenticity”

By the early 1960s, the Warsaw city historian was claiming that “the old town now looks as it used to long ago” [23]. While this is a commonly cited view, it is not completely correct. Despite his reputation for accuracy and precision, Bellotto actually allowed himself considerable artistic licence in his paintings. One commentator, noting that that “the border line between topographical accuracy and fantasy is not easy”, gives numerous examples – when depicting the entry of the Polish ambassador into Rome in 1633, Bellotto painted two churches in the Piazza del Popolo, although they were not built till some 30 years later; in his picture of the election of the last king of Poland he transformed Warsaw’s flat fields into a picturesque hilly landscape; and he sometimes abandoned direct transcriptions of nature in order to present an ingeniously constructed scene from an artificial perspective [24]. Bellotto also consciously “improved” some scenes. So, for example, in Fig 4 his Miodowa Street façade of Branicki Palace apparently shows sculptural work derived from his own imagination; these were laboriously copied in the reconstruction nearly two centuries after their invention by the painter [25].

Another source of divergence was the compromises and decisions – often-ideological and sometimes pragmatic – made by the planners. Many of the buildings originally depicted by Bellotto had been remodelled in the nineteenth century, and were restored back to an earlier state. For example, the reconstruction of St John's Cathedral, carried out between 1947 and 1955, removed substantial neo-gothic alterations which had been made in the nineteenth century, because “in the imagination of Stalinist patriotism”, these were regarded as being redolent of “Englishness” and “cosmopolitanism” [26]. The removal enabled the building to more resemble the “Vistula gothic” of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, which was considered to be closer to what the government wished to present as a desirable historic building.

Together, variations stemming from factors such as these produced results in which it is difficult to sort out what should be regarded as “authentic”. One example is John’s House on Castle Square. Fig 10a shows Bellotto’s 18th century version. Fig 10b is a photograph taken in about 1920 showing some variations and additions, but also indicating that Bellotto must have omitted one entire line of windows; and Fig 10c shows the building as reconstructed, which reverts to Bellotto’s original, presumably incorrect, version.

Another source of divergence was the compromises and decisions – often-ideological and sometimes pragmatic – made by the planners. Many of the buildings originally depicted by Bellotto had been remodelled in the nineteenth century, and were restored back to an earlier state. For example, the reconstruction of St John's Cathedral, carried out between 1947 and 1955, removed substantial neo-gothic alterations which had been made in the nineteenth century, because “in the imagination of Stalinist patriotism”, these were regarded as being redolent of “Englishness” and “cosmopolitanism” [26]. The removal enabled the building to more resemble the “Vistula gothic” of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, which was considered to be closer to what the government wished to present as a desirable historic building.

Together, variations stemming from factors such as these produced results in which it is difficult to sort out what should be regarded as “authentic”. One example is John’s House on Castle Square. Fig 10a shows Bellotto’s 18th century version. Fig 10b is a photograph taken in about 1920 showing some variations and additions, but also indicating that Bellotto must have omitted one entire line of windows; and Fig 10c shows the building as reconstructed, which reverts to Bellotto’s original, presumably incorrect, version.

Fig 10. From left: (a) John’s House on Castle Square, mid-18th century, as depicted in Bernardo Bellotto’s 1768 painting Krakowskie Przedmieście from the side of the Kraków gate, (b) John’s House during the second decade of 20th century; (c) John’s House in 2009, after reconstruction. http://99percentinvisible.org/episode/episode-72-new-old-town/

6. Evaluation

In 1983 Bellotto’s paintings were finally returned from the National Museum to their original home at the Royal Castle, where they may now been seen in the “Canaletto Room” of the Royal Apartments, in Castle Square at the entrance to the old town. Outside the Castle is the historic centre which the paintings were originally intended to reflect, but which they would later be used to reconstruct. This is a very intimate relationship indeed between art and society.

So what are we dealing with here? Is it a restoration? A reconstruction? A reinvention? A resuscitation? A remodelling? Perhaps it contains elements of all of these. And how do we evaluate it? In 1980, UNESCO included the historic city (the Old City and the Royal Castle) in the World Heritage list as an “outstanding example of a near-total reconstruction of a span of history covering the 13th to the 20th century”. It is hard to quibble about the effort involved and the impressiveness of the achievement. Yet some have criticised it, with some justification, on the basis that it is an artificial confection. It is true that there is that element, though in practical terms this would probably exist to some extent no matter how scrupulously the project may have been implemented. Perhaps, however, from our point of view, there are two aspects that are more important than this. The first is that it was art – in the form of Bellotto’s paintings – which helped inspire and enabled the attempt to reconstruct. The second is that this effort represents a triumph, however imperfect, of a downtrodden but indefatigable people’s expression of pride in their cultural identity.□

© Philip McCouat 2015

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Bernardo Bellotto and the Reconstruction of Warsaw”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsocety.com

Thanks to Punia Jeffery for suggesting this topic!

We welcome your comments on this article

For other articles on art and war, see:

The Isenheim Altarpiece Pt 2: Nationalism, Nazism and Degeneracy

The shocking birth and amazing career of Guernica

From the Rokeby Venus to Fascism Pt 2: the strange allure of fascism

Back to HOME

So what are we dealing with here? Is it a restoration? A reconstruction? A reinvention? A resuscitation? A remodelling? Perhaps it contains elements of all of these. And how do we evaluate it? In 1980, UNESCO included the historic city (the Old City and the Royal Castle) in the World Heritage list as an “outstanding example of a near-total reconstruction of a span of history covering the 13th to the 20th century”. It is hard to quibble about the effort involved and the impressiveness of the achievement. Yet some have criticised it, with some justification, on the basis that it is an artificial confection. It is true that there is that element, though in practical terms this would probably exist to some extent no matter how scrupulously the project may have been implemented. Perhaps, however, from our point of view, there are two aspects that are more important than this. The first is that it was art – in the form of Bellotto’s paintings – which helped inspire and enabled the attempt to reconstruct. The second is that this effort represents a triumph, however imperfect, of a downtrodden but indefatigable people’s expression of pride in their cultural identity.□

© Philip McCouat 2015

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Bernardo Bellotto and the Reconstruction of Warsaw”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsocety.com

Thanks to Punia Jeffery for suggesting this topic!

We welcome your comments on this article

For other articles on art and war, see:

The Isenheim Altarpiece Pt 2: Nationalism, Nazism and Degeneracy

The shocking birth and amazing career of Guernica

From the Rokeby Venus to Fascism Pt 2: the strange allure of fascism

Back to HOME

End Notes

1 Poland itself had been “liberated” from the Germans in January 1945 when Soviet forces entered Warsaw. In the Pacific, the War with Japan continued until August 1945.

2 England and France declared war on Germany two days later, pursuant to their guarantee of Poland’s border.

3 Also known as the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact after the respective foreign ministers. See generally Roger Moorhouse, The Devils’ Alliance: Hitler‘s Pact with Stalin, 1939-41, Bodley Head, London, 2014; Roger Moorhouse, “When Poland was torn to pieces”, BBC History Magazine, October 2014, 40-44.

4 This became known as the massacre at Katyn.

5 Moorehouse, op cit, BBC History at 44.

6 Lynn H Nicholas, The Rape of Europa, Papermac, London 1994 at 61.

7 Adam Zamoyski, Poland: a History, Harper Press, London, 2009 at 338.

8 Zamoyski, op cit at 338.

9 Nicola Lanbourne, War Damage in Western Europe: the destruction of historic monuments during World War II, Edinburgh University Press, 2001 at 42-3.

10 UNESCO Art Museums in Need, 1949, at 6.

11 See also Zamoyski, op cit at 338.

12. Nicholas, op cit at 68-71.

13. Nicholas, op cit at 58.

14. Zamoyski, op cit at 338.

15 Michal Murawski, “(A)political buildings: ideology, memory and Warsaw's 'Old' Town”. Mirror of Modernity: The Postwar Revolution in Urban Conservation, Proceedings of Joint Conference, May 2009. http://www.fredmussat.fr/e-proceedings2_dec09/mirror_of_modernity_murawski.htm

16 Piotr Majewski, “The Use of Bernardo Bellotto’s Paintings in the Reconstruction of Warsaw after World War II” in Stéphane Loire et al (eds), Bernardo Bellotto: a Venetian Painter in Warsaw, 5 Continents, Milan, 2004 at 27.

17 Majewski, op cit at 28.

18 Martyn, P. 2001 “The Brave New-Old Capital City: Questions relating to the rebuilding and remodelling of Warsaw’s architectural profile from the late-1940s until 1956”, in Jerzy Miziołek (Ed.), Falsifications in Polish Collections and Abroad, Warsaw: Institute of Archaeology, Warsaw University.

19 A camera obscura (“dark box”) consists of a box with a hole in one end. Light from an outside source passes through the hole and hits the opposite end of the box, presenting an upside-down image of the scene outside. This image can be projected onto a piece of paper, and traced to produce an extremely accurate representation.

20 Majewski, op cit at 30.

21 In Poland, he is often referred to as Canaletto.

22 Majewski, at 34-5.

23 Martyn, op cit at 211-2; Murawski, op cit.

24. Jan Bialostocki, “Bernardo Bellotto in Dresden and Warsaw”, The Burlington Magazine, Vol 106, No 735, June 1964, 289-90.

25 Martyn, op cit at 211-2.

26 Murawski, op cit.

© Philip McCouat 2015

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Bernardo Bellotto and the Reconstruction of Warsaw”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsocety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

2 England and France declared war on Germany two days later, pursuant to their guarantee of Poland’s border.

3 Also known as the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact after the respective foreign ministers. See generally Roger Moorhouse, The Devils’ Alliance: Hitler‘s Pact with Stalin, 1939-41, Bodley Head, London, 2014; Roger Moorhouse, “When Poland was torn to pieces”, BBC History Magazine, October 2014, 40-44.

4 This became known as the massacre at Katyn.

5 Moorehouse, op cit, BBC History at 44.

6 Lynn H Nicholas, The Rape of Europa, Papermac, London 1994 at 61.

7 Adam Zamoyski, Poland: a History, Harper Press, London, 2009 at 338.

8 Zamoyski, op cit at 338.

9 Nicola Lanbourne, War Damage in Western Europe: the destruction of historic monuments during World War II, Edinburgh University Press, 2001 at 42-3.

10 UNESCO Art Museums in Need, 1949, at 6.

11 See also Zamoyski, op cit at 338.

12. Nicholas, op cit at 68-71.

13. Nicholas, op cit at 58.

14. Zamoyski, op cit at 338.

15 Michal Murawski, “(A)political buildings: ideology, memory and Warsaw's 'Old' Town”. Mirror of Modernity: The Postwar Revolution in Urban Conservation, Proceedings of Joint Conference, May 2009. http://www.fredmussat.fr/e-proceedings2_dec09/mirror_of_modernity_murawski.htm

16 Piotr Majewski, “The Use of Bernardo Bellotto’s Paintings in the Reconstruction of Warsaw after World War II” in Stéphane Loire et al (eds), Bernardo Bellotto: a Venetian Painter in Warsaw, 5 Continents, Milan, 2004 at 27.

17 Majewski, op cit at 28.

18 Martyn, P. 2001 “The Brave New-Old Capital City: Questions relating to the rebuilding and remodelling of Warsaw’s architectural profile from the late-1940s until 1956”, in Jerzy Miziołek (Ed.), Falsifications in Polish Collections and Abroad, Warsaw: Institute of Archaeology, Warsaw University.

19 A camera obscura (“dark box”) consists of a box with a hole in one end. Light from an outside source passes through the hole and hits the opposite end of the box, presenting an upside-down image of the scene outside. This image can be projected onto a piece of paper, and traced to produce an extremely accurate representation.

20 Majewski, op cit at 30.

21 In Poland, he is often referred to as Canaletto.

22 Majewski, at 34-5.

23 Martyn, op cit at 211-2; Murawski, op cit.

24. Jan Bialostocki, “Bernardo Bellotto in Dresden and Warsaw”, The Burlington Magazine, Vol 106, No 735, June 1964, 289-90.

25 Martyn, op cit at 211-2.

26 Murawski, op cit.

© Philip McCouat 2015

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Bernardo Bellotto and the Reconstruction of Warsaw”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsocety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME