Surviving the Black Death

|

By Philip McCouat

In the 1340s, a catastrophic wave of bubonic plague swept through Europe. Originating near Mongolia, it wiped out at least a third of the population. It was – and remains – the greatest single natural disaster in history. If replicated on the same scale today, it would have killed an almost inconceivable two billion people. Known at the time as The Great Mortality, it is today usually referred to as the Black Death [1]. |

---------------------------------------------

For more on diseases ---------------------------------------------------------- |

By May 1348, it had reached the thriving Italian city of Siena. Coming on top of a series of disastrous events, including banking crises, bankruptcies, crop failures and hailstorms, the misery and mass deaths caused by the Black Death were seen as a terrible warning of the wrath of God for the moral corruption of man. For some, it even came to be regarded, quite literally, as the end of the world [2].

In this article, we’ll be examining how these grim developments affected the life and work of one of the fortunate survivors – the Sienese painter Bartolo di Fredi.

In this article, we’ll be examining how these grim developments affected the life and work of one of the fortunate survivors – the Sienese painter Bartolo di Fredi.

Painters and the Black Death

In Siena, as in other places, the Black Death had immediate and devastating effects on artists. The most obvious, of course, was that many painters, prominent or otherwise, died. The probable victims included Sienese masters such as Ambrogio Lorenzetti and his brother Pietro, the Sienese-influenced Florentine master Bernardo Daddi, and possibly Lippo Memmi. These came on top of some earlier notable losses – Simone Martini n 1344, Donato Martini in 1347 and Niccolo di Segna, probably in 1345 [3]. It is almost certain that the Black Death would also have severely depleted future numbers of potential new painters.

In the immediate aftermath of the outbreak, artistic activity virtually stopped. So, for example, major expansion projects such as the Duomo (Cathedral) of Siena, funded by civic authorities, were halted or drastically scaled back [4]. Traditional levels of patronage also declined, especially after 1355 when many wealthy and powerful families started to lose their influence [5]. This decline forced those artists who managed to survive to travel and work further afield.

Bartolo di Fredi, who was only 18 at the time of the outbreak [6], was in many ways blessed with luck. He was not himself afflicted, and survival brought its own benefits. As Meiss says, “this sudden removal [of artists] at one stroke … gave to the surviving masters, especially the younger ones, a sudden exceptional independence”[7]. More practically, perhaps, it meant that there were fewer artists around, and – because of deaths of younger persons during the Black Death – fewer painters coming through. For Bartolo, who was emerging as a painter after 1348, there would have been a sustained period in which there was a relative lack of competition. This factor alone is likely to have had a significant and positive effect on his career.

Addded to this, Bartolo’s comparatively young age when the outbreak occurred meant that the sudden lack of commissions that did occur was not financially crippling, as it may have been for older painters who had already become dependant on continued patronage. In fact, by the time that Bartolo’s career was starting in earnest, the general patterns of commissioning had altered for the better. Cohn’s research has demonstrated that the second wave of the Black Death, which had returned in 1362-63, produced a crisis in thinking about mortality that in fact led to an increase in demand for sacred art as a vehicle for self-memorialisation. This probably ensured more security for painters, including Bartolo [8].

Whatever the reasons, Bartolo does not appear to have been significantly adversely affected by a lack of commissions. It seems clear that he was able to run an extremely busy and successful workshop for many years. Indeed, he was more likely to suffer from an oversupply rather than an undersupply [9]. Even at the Siena Duomo itself, an alternative source of significant commissions from the commercial guilds would eventually result in major works for him, for example, in chapel altarpieces for the Bakers’, Masons’ and Shoemakers’ Guilds [10]. One of his best-known works, The Adoration of the Magi, with its depiction of Siena itself in the background, was also commissioned for the Duomo (Fig 1).

In the immediate aftermath of the outbreak, artistic activity virtually stopped. So, for example, major expansion projects such as the Duomo (Cathedral) of Siena, funded by civic authorities, were halted or drastically scaled back [4]. Traditional levels of patronage also declined, especially after 1355 when many wealthy and powerful families started to lose their influence [5]. This decline forced those artists who managed to survive to travel and work further afield.

Bartolo di Fredi, who was only 18 at the time of the outbreak [6], was in many ways blessed with luck. He was not himself afflicted, and survival brought its own benefits. As Meiss says, “this sudden removal [of artists] at one stroke … gave to the surviving masters, especially the younger ones, a sudden exceptional independence”[7]. More practically, perhaps, it meant that there were fewer artists around, and – because of deaths of younger persons during the Black Death – fewer painters coming through. For Bartolo, who was emerging as a painter after 1348, there would have been a sustained period in which there was a relative lack of competition. This factor alone is likely to have had a significant and positive effect on his career.

Addded to this, Bartolo’s comparatively young age when the outbreak occurred meant that the sudden lack of commissions that did occur was not financially crippling, as it may have been for older painters who had already become dependant on continued patronage. In fact, by the time that Bartolo’s career was starting in earnest, the general patterns of commissioning had altered for the better. Cohn’s research has demonstrated that the second wave of the Black Death, which had returned in 1362-63, produced a crisis in thinking about mortality that in fact led to an increase in demand for sacred art as a vehicle for self-memorialisation. This probably ensured more security for painters, including Bartolo [8].

Whatever the reasons, Bartolo does not appear to have been significantly adversely affected by a lack of commissions. It seems clear that he was able to run an extremely busy and successful workshop for many years. Indeed, he was more likely to suffer from an oversupply rather than an undersupply [9]. Even at the Siena Duomo itself, an alternative source of significant commissions from the commercial guilds would eventually result in major works for him, for example, in chapel altarpieces for the Bakers’, Masons’ and Shoemakers’ Guilds [10]. One of his best-known works, The Adoration of the Magi, with its depiction of Siena itself in the background, was also commissioned for the Duomo (Fig 1).

A further consequence of the Black Death turned out to be personally advantageous for Bartolo, and in an unexpected way. Wainwright has noted that the dislocation caused by the Black Death was pivotal in social and political changes that took place in Siena, culminating in the fall of the government in 1355. Thereafter, members of the artisan classes could hold public office [11]. This crucial change enabled Bartolo, a mere artist, to gain significant power as a result of his association with the popular faction [12]. It seems to have been no coincidence that he also became the recipient of a series of large-scale commissions around this time [13].

The fact that many artists had to travel in order to obtain work also did not seem to have had a detrimental effect on Bartolo. It is true that many of his most important commissions were for altarpieces for provincial towns lying outside the city [14]. However, Bartolo’s need to travel on artistic business was largely limited to the surrounds of Siena [15]. In an event, any travel he made to surrounding districts in the course of his political duties may actually have been beneficial. Wainwright is clearly of the view that Bartolo’s contacts established in towns such as San Gimignano on non-artistic business “bore fruit in the form of painting commissions”[16].

The fact that many artists had to travel in order to obtain work also did not seem to have had a detrimental effect on Bartolo. It is true that many of his most important commissions were for altarpieces for provincial towns lying outside the city [14]. However, Bartolo’s need to travel on artistic business was largely limited to the surrounds of Siena [15]. In an event, any travel he made to surrounding districts in the course of his political duties may actually have been beneficial. Wainwright is clearly of the view that Bartolo’s contacts established in towns such as San Gimignano on non-artistic business “bore fruit in the form of painting commissions”[16].

The general standard of art

If then the Black Death did not have an unfavourable effect on the amount of work for Bartolo, did it affect its quality?

This is a controversial issue and one on which subjective preferences can sometimes intrude. The first question that has to be considered is as to the merits of post-1348 art in general. In his influential book Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, Millard Meiss argued that painting in the third quarter of the 14th century demonstrated a clear break with the art of the previous 50 years. This break, he said, was characterised by painting that reflected a renewed religious conservatism which stressed hierarchical, spiritual, supernatural and judgmental representations. It also involved a rejection of some of the advances made by Giotto and the Lorenzettis in the early part of the century, in areas such as perspective and naturalistic representations. Finally, Meiss argued, post-1348 art embodied a gloomy pessimism, tension and fear, including an increased obsession with death.

Meiss’ general conclusion was that it was “not one of the great periods”. While accepting that the characteristics of period were “coherent and purposeful” and worthy of appreciation in their own right, he describes them as being foreign to the evolution of art and contrary to classical taste [17]. Other influential views were that in this period art grew “worse day by day” or “fell back into decline” [18].

Although Meiss’ view was that this decline could be traced directly to the mindset created by the Black Death [19], there is an associated view that the nature of commissions after 1348 also contributed led to a general decline in quality. Various commentators have pointed out that the dislocations of the period led to the emergence of a rising new class of patrons – the gente nuova – who in artistic terms were either more religiously and aesthetically conservative, less sophisticated or simply less concerned with artistic purity than the traditional patrons of the earlier part of the century [20].

In van Os’ view, for example, this change resulted in a break in the continuity of large commissions that would, in normal times, guarantee the lasting existence of large, cohesive workshops. Instead, there emerged ad hoc collaborations by individual artists who worked in their own stylistic idioms, leading to a loss of overall coherence. He notes, for example, that the 1389 Duomo altarpiece referred to previously was a joint commission for Bartolo, his son Andrea and Luca di Tomme, whose style was very different from Bartolo’s [21]. Steinhoff goes further, arguing that this development actually constituted a basic change in the system of artistic production, forcing painters to form the new style collaborations to help them weather the perceived uncertainties and the accompanying economic instability [22].

Whatever the merits of these arguments, however, the impact on Bartolo does not appear to have been great. Indeed, in some ways, it is odd that van Os chose to use Bartolo as evidence of his view because, as we have seen, Bartolo in fact did run a large and successful workshop for many years. Both Freuler and Wainwright also point out that the reason that Bartolo sometimes collaborated with other leading artists was simply that he was inundated with commissions – some he did through the workshop, others by collaboration [23]. This was not a matter of necessity, rather one of good management.

This is a controversial issue and one on which subjective preferences can sometimes intrude. The first question that has to be considered is as to the merits of post-1348 art in general. In his influential book Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, Millard Meiss argued that painting in the third quarter of the 14th century demonstrated a clear break with the art of the previous 50 years. This break, he said, was characterised by painting that reflected a renewed religious conservatism which stressed hierarchical, spiritual, supernatural and judgmental representations. It also involved a rejection of some of the advances made by Giotto and the Lorenzettis in the early part of the century, in areas such as perspective and naturalistic representations. Finally, Meiss argued, post-1348 art embodied a gloomy pessimism, tension and fear, including an increased obsession with death.

Meiss’ general conclusion was that it was “not one of the great periods”. While accepting that the characteristics of period were “coherent and purposeful” and worthy of appreciation in their own right, he describes them as being foreign to the evolution of art and contrary to classical taste [17]. Other influential views were that in this period art grew “worse day by day” or “fell back into decline” [18].

Although Meiss’ view was that this decline could be traced directly to the mindset created by the Black Death [19], there is an associated view that the nature of commissions after 1348 also contributed led to a general decline in quality. Various commentators have pointed out that the dislocations of the period led to the emergence of a rising new class of patrons – the gente nuova – who in artistic terms were either more religiously and aesthetically conservative, less sophisticated or simply less concerned with artistic purity than the traditional patrons of the earlier part of the century [20].

In van Os’ view, for example, this change resulted in a break in the continuity of large commissions that would, in normal times, guarantee the lasting existence of large, cohesive workshops. Instead, there emerged ad hoc collaborations by individual artists who worked in their own stylistic idioms, leading to a loss of overall coherence. He notes, for example, that the 1389 Duomo altarpiece referred to previously was a joint commission for Bartolo, his son Andrea and Luca di Tomme, whose style was very different from Bartolo’s [21]. Steinhoff goes further, arguing that this development actually constituted a basic change in the system of artistic production, forcing painters to form the new style collaborations to help them weather the perceived uncertainties and the accompanying economic instability [22].

Whatever the merits of these arguments, however, the impact on Bartolo does not appear to have been great. Indeed, in some ways, it is odd that van Os chose to use Bartolo as evidence of his view because, as we have seen, Bartolo in fact did run a large and successful workshop for many years. Both Freuler and Wainwright also point out that the reason that Bartolo sometimes collaborated with other leading artists was simply that he was inundated with commissions – some he did through the workshop, others by collaboration [23]. This was not a matter of necessity, rather one of good management.

How good was Bartolo?

The second question is the separate issue of Bartolo’s own artistic ability. It is certainly true that Bartolo did not exhibit much interest in detailed formal perspective. His treatment of architectural detail was often naïve, and he showed a characteristic lack of interest in developing a convincing middle ground. For Meiss, comparing this with the groundbreaking pre-1348 works of Giotto and the Lorenzettis, this demonstrated that Bartolo’s work represented an evolutionary dead-end or throwback to the previous century.

However, considerable caution is warranted here. Judging evolutionary “success” is an exercise that can only be conducted with the comforting advantage of hindsight. When Meiss was writing in the 1950s, in the secure knowledge of the ultimate direction of art after the fourteenth century, it would seem clear that pre-1348 artists such as Giotto and Lorenzetti represented the way of the future, and that artists such as Bartolo definitely did not. However, for Bartolo and his post-1348 contemporaries, it may well have seemed that Lorenzettian concerns with perspective could be perceived as just a short-lived experiment that they were not inspired or compelled to follow. Considered in its contemporary context, the mere fact that these artists’ works may not have followed Giotto-esque precedent, and that they therefore itself may have had only a limited influence, should not necessarily imply inferiority.

It is true that that many of Bartolo’s works, particularly in the provinces, were versions of earlier works by others. There were various reasons for this. One was simply the fact that his provincial patrons specifically commissioned him to do it. Norman suggests, for example, that Bartolo’s Presentation at the Temple (Fig 2) derived its prestige as a religious painting precisely because it supplied a version of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s pre-1348 altarpiece (Fig 3)[24].

However, considerable caution is warranted here. Judging evolutionary “success” is an exercise that can only be conducted with the comforting advantage of hindsight. When Meiss was writing in the 1950s, in the secure knowledge of the ultimate direction of art after the fourteenth century, it would seem clear that pre-1348 artists such as Giotto and Lorenzetti represented the way of the future, and that artists such as Bartolo definitely did not. However, for Bartolo and his post-1348 contemporaries, it may well have seemed that Lorenzettian concerns with perspective could be perceived as just a short-lived experiment that they were not inspired or compelled to follow. Considered in its contemporary context, the mere fact that these artists’ works may not have followed Giotto-esque precedent, and that they therefore itself may have had only a limited influence, should not necessarily imply inferiority.

It is true that that many of Bartolo’s works, particularly in the provinces, were versions of earlier works by others. There were various reasons for this. One was simply the fact that his provincial patrons specifically commissioned him to do it. Norman suggests, for example, that Bartolo’s Presentation at the Temple (Fig 2) derived its prestige as a religious painting precisely because it supplied a version of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s pre-1348 altarpiece (Fig 3)[24].

The further view that this lack of originality led to an inferior, less dynamic, simplified style is, however, open to doubt [25]. This may be illustrated by examining the two works just mentioned – a comparison commonly cited as evidence of the supposed decline [26].

Meiss claims that although Bartolo’s work is based on Ambrogio’s, it is lacking in some important ways. He argues that Bartolo curtails Ambrogio’s deep space, and distorts the system of perspective – “the inlaid floor that defined the recession and the position of the figures in space has been eliminated. The figures have been drawn into one or two shallow planes and knit tightly together by their more salient outlines and drapery folds”. Furthermore, he considers that “whereas in Ambrogio’s concentrated design the figures are united in contemplation of Anna’s prophecy, Bartolo has created three separate competitive centres – around the child, the priest, and the prophetess Anna. Even within these centres, the figures are withdrawn from each other”. Finally, Meiss argues that Bartolo has increased the importance of the altar, and elevated the priest to “a position of dominance in the entire scene”[27]. The result, suggests Meiss, is the Bartolo’s version is flatter, more conservative, oversimplified and less intense.

This analysis, however, overlooks a crucial difference between the paintings. This lies in the depiction of the Child. Ambrogio showed the Child as passive, not playing any active role in the proceedings, or even showing an interest in them. In contrast, Bartolo’s Child is alert, actively reaching out for his mother who clasps his hands. It is arguable that this aspect gives the painting a liveliness that is totally absent from Ambrogio’s earlier work [28], and that the contact of hands and exchanging of glances between mother and son becomes the focal point in the centre of the composition [29]. Indeed, as Wainwright has pointed out [30], it is a very similar feature – the reaching out of the child to its Mother – which Meiss considers to be the familiar, human and intimate central incident, when he is discussing Taddeo Gaddi’s pre-1348 Presentation [31].

It can also be argued that the effect of light on the altar, which Meiss dismisses as a mere glare which fails to create atmosphere, can instead be seen as further highlighting the central focus on the mother-son connection. The elevation of the priest, far from giving him a position of dominance, takes him out of the central focus of the painting. On this alternative analysis, therefore, it is arguable that contrary to Meiss’s view, Bartolo’s version exhibits more human intimacy and less dominance of the priest [32]. It seems clear, therefore, that the Presentation may be interpreted in a much more positive way than either Meiss or Van Os allows [33].

Similar comments may be made about Bartolo’s Old Testament cycle of frescoes for the Collegiata in San Gimignano (ca 1367). This cycle originally consisted of 30 scenes from the Creation and episodes in the life of Old Testament characters such Noah, Abraham, Moses, Joseph and Job [34]. As an extensive cycle on traditional subjects, firmly dated inside Meiss’s critical quarter century, one would expect this work to provide a good test of his views as to the decline in quality.

Meiss’s only reference to the work, however, is to its subject matter, and not at all to its style. He suggests that the choice of Job was attributable to the fact that Job’s disease and recurring tribulations had interesting parallels with the Black Death (though it is noteworthy that this does not apply to the other patriarchs featured). He then seeks to reinforce the work’s Black Death significance by claiming that this subject had “rarely if ever [been] represented in earlier Tuscan panels or frescoes”[35]. However, in this respect Meiss is mistaken. It has since been plausibly demonstrated that Bartolo’s Job cycle was in fact based on Taddeo Gaddi’s work at the Camposanto at Pisa, which is most probably pre-1348 [36]. To compound this difficulty, Taddeo is a painter whom Meiss himself accepts as “the most devoted pupil of Giotto” who stood “wholly outside” the artistic trend that Meiss considers emerged after 1348 [37].

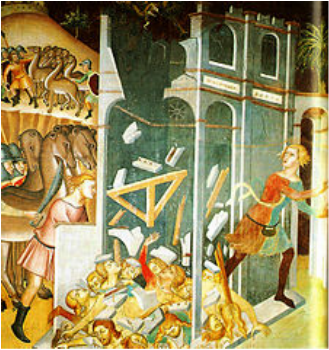

Furthermore, as Fengler has pointed out, the style of Bartolo’s work adds no support at all to Meiss’s expectation of “ a strict uniformity and regimentation of the figures .. a denial of the values of individuality.. and an accent on the miraculous rather than the natural”[38]. Although the work exhibits Bartolo’s characteristic flattening of perspective and architectural idiosyncracy, it is actually remarkable for the liveliness of its figures, and the cramming in of colourful human incident and realistic detail, coupled with an almost naive lack of solemnity or high drama. This is particularly surprising in view of the potentially alarming nature of the subject matter. The scene of Collapse of Job’s House (Fig 4) is typical, somehow contriving to convert a scene of appalling death to one in which the chief interest focuses on the massed sinuous lines of camels, picturesquely-falling woodwork and a handsome fleeing son.

Meiss claims that although Bartolo’s work is based on Ambrogio’s, it is lacking in some important ways. He argues that Bartolo curtails Ambrogio’s deep space, and distorts the system of perspective – “the inlaid floor that defined the recession and the position of the figures in space has been eliminated. The figures have been drawn into one or two shallow planes and knit tightly together by their more salient outlines and drapery folds”. Furthermore, he considers that “whereas in Ambrogio’s concentrated design the figures are united in contemplation of Anna’s prophecy, Bartolo has created three separate competitive centres – around the child, the priest, and the prophetess Anna. Even within these centres, the figures are withdrawn from each other”. Finally, Meiss argues that Bartolo has increased the importance of the altar, and elevated the priest to “a position of dominance in the entire scene”[27]. The result, suggests Meiss, is the Bartolo’s version is flatter, more conservative, oversimplified and less intense.

This analysis, however, overlooks a crucial difference between the paintings. This lies in the depiction of the Child. Ambrogio showed the Child as passive, not playing any active role in the proceedings, or even showing an interest in them. In contrast, Bartolo’s Child is alert, actively reaching out for his mother who clasps his hands. It is arguable that this aspect gives the painting a liveliness that is totally absent from Ambrogio’s earlier work [28], and that the contact of hands and exchanging of glances between mother and son becomes the focal point in the centre of the composition [29]. Indeed, as Wainwright has pointed out [30], it is a very similar feature – the reaching out of the child to its Mother – which Meiss considers to be the familiar, human and intimate central incident, when he is discussing Taddeo Gaddi’s pre-1348 Presentation [31].

It can also be argued that the effect of light on the altar, which Meiss dismisses as a mere glare which fails to create atmosphere, can instead be seen as further highlighting the central focus on the mother-son connection. The elevation of the priest, far from giving him a position of dominance, takes him out of the central focus of the painting. On this alternative analysis, therefore, it is arguable that contrary to Meiss’s view, Bartolo’s version exhibits more human intimacy and less dominance of the priest [32]. It seems clear, therefore, that the Presentation may be interpreted in a much more positive way than either Meiss or Van Os allows [33].

Similar comments may be made about Bartolo’s Old Testament cycle of frescoes for the Collegiata in San Gimignano (ca 1367). This cycle originally consisted of 30 scenes from the Creation and episodes in the life of Old Testament characters such Noah, Abraham, Moses, Joseph and Job [34]. As an extensive cycle on traditional subjects, firmly dated inside Meiss’s critical quarter century, one would expect this work to provide a good test of his views as to the decline in quality.

Meiss’s only reference to the work, however, is to its subject matter, and not at all to its style. He suggests that the choice of Job was attributable to the fact that Job’s disease and recurring tribulations had interesting parallels with the Black Death (though it is noteworthy that this does not apply to the other patriarchs featured). He then seeks to reinforce the work’s Black Death significance by claiming that this subject had “rarely if ever [been] represented in earlier Tuscan panels or frescoes”[35]. However, in this respect Meiss is mistaken. It has since been plausibly demonstrated that Bartolo’s Job cycle was in fact based on Taddeo Gaddi’s work at the Camposanto at Pisa, which is most probably pre-1348 [36]. To compound this difficulty, Taddeo is a painter whom Meiss himself accepts as “the most devoted pupil of Giotto” who stood “wholly outside” the artistic trend that Meiss considers emerged after 1348 [37].

Furthermore, as Fengler has pointed out, the style of Bartolo’s work adds no support at all to Meiss’s expectation of “ a strict uniformity and regimentation of the figures .. a denial of the values of individuality.. and an accent on the miraculous rather than the natural”[38]. Although the work exhibits Bartolo’s characteristic flattening of perspective and architectural idiosyncracy, it is actually remarkable for the liveliness of its figures, and the cramming in of colourful human incident and realistic detail, coupled with an almost naive lack of solemnity or high drama. This is particularly surprising in view of the potentially alarming nature of the subject matter. The scene of Collapse of Job’s House (Fig 4) is typical, somehow contriving to convert a scene of appalling death to one in which the chief interest focuses on the massed sinuous lines of camels, picturesquely-falling woodwork and a handsome fleeing son.

Some of these comments also apply to the Adoration of the Magi, mentioned earlier (Fig 1). Meiss notes this only in a footnote [39], commenting on the prominent use of gold in the garments, crown and possessions of the main figures. He does not comment on its lively sense of anecdotal detail – for example, in the actions of the horses and their attendant in the foreground, and the extraordinary procession including dogs, camels and monkeys in the background. Perhaps these are not features that can easily be reconciled with a Black Death mindset.

Conclusion

This analysis suggests that some of the criticisms of Bartolo’s work may have been somewhat overdone. It is true that Bartolo is not generally regarded as being in the same exalted company as, say, Giotto or the Lorenzettis [40]. However, it appears that more recent studies have to some extent restored his reputation as a worthy master, who would come to be regarded as one of the most popular and prolific Sienese painters of the second half of the 14th century [41].

In summing up, it seems that Bartolo’s relationship with the Black Death was in many ways that of a beneficiary. The particular combination of personal and external circumstances proved fortunate for him. Bartolo’s long life, high level of energy, organisational workshop skills, luck, timing, political influence and significant artistic talent combined to put him in an ideal position to take artistic advantage of the dislocations of the times.□

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015

If you enjoyed this article you may also be interested in Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night.

We welcome your comments on this article.

In summing up, it seems that Bartolo’s relationship with the Black Death was in many ways that of a beneficiary. The particular combination of personal and external circumstances proved fortunate for him. Bartolo’s long life, high level of energy, organisational workshop skills, luck, timing, political influence and significant artistic talent combined to put him in an ideal position to take artistic advantage of the dislocations of the times.□

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015

If you enjoyed this article you may also be interested in Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night.

We welcome your comments on this article.

End Notes

1. The literature on the Black Death is intimidatingly vast. Useful starting points are Tuchman, B, A Distant Mirror: the Calamitous 14th Century, Ballantine Books, New York, 1978 (and later reissues); and Kelly, J, The Great Mortality: an Intimate History of the Black Death, Harper Perennial, London 2006.

2. Kelly, op cit, at 26.

3. Meiss, M., Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, Harper and Row 1973, at 66; Maginnis, H.B.J., Painting in the age of Giotto: a historical re-evaluation, University Park, 1997, at 191.

4. Norman, D, (ed) Siena, Florence and Padua: Art, Society and Religion 1280-1400, Vol 1, Yale University Press 1995, at 19.

5. Bowsky, W M, “The impact of the Black Death upon Sienese government and society”, Speculum 39, 1964, 1-34.

6. Bartolo was probably born in 1330 and died in 1410.

7. Meiss, op cit at 66.

8. Steinhoff, J., “Artistic Working Relationships after the Black Death: a Sienese compagnia”, Renaissance Studies 2000, 14, no. 1, 1-45, at 44.

9. Freuler, G., and Wainwright, V., Letter to Editor, Art Bulletin 68, 1986, 327-8.

10. In 1368, 1374 and 1389: Harpring, P, The Sienese Trecento Painter Bartolo di Fredi, Associated University Presses Inc, 1993, at 16.

11. Wainwright, V., “Andrea Vanni and Bartolo di Fredi: Sienese painters in their Social Context”, PhD diss, University of London, 1978, at 36.

12. Wainwright, op cit, at 10; Harpring, op cit at 16.

13. Freuler and Wainwright, op cit at 328.

14. Norman, D., “Change and continuity: art and religion after the Black Death” 177-196, in Norman, D., (ed) Siena, Florence and Padua: Art, Society and Religion 1280-1400, Vol 1, Yale University Press 1995, at 195.

15. A detailed study by Wainwright concluded that “on the whole, Sienese painters in the latter half of the Trecento do not appear to have been as adventurous as their illustrious predecessors; with few exceptions they were perhaps reluctant to undertake long and potentially hazardous journeys to work in other cities in the peninsula”: Wainwright, op cit at 162.

16. Wainwright, op cit, at 154.

17. Meiss, op cit at xi.

18. Maginnis, op cit at 164.

19. A detailed examination of this much disputed view is outside the scope of this article.

20. Maginnis, op cit at 164-191.

21. Van Os, H. W, “Tradition and innovation in some altarpieces by Bartolo di Fredi”, Art Bulletin 67, 1985, at 56, 64.

22. Steinhoff, op cit at 7. This view has been further developed in the same author's Sienese Painting after the Black Death: Artistic Pluralism, Politics and the New Art Market, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

23. Freuler and Wainwright, op cit at 327.

24. Norman, op cit at 195. Another reason may simply have been that the abundance of commissions, combined with the demands of his political career, led Bartolo into taking shortcuts.

25. There seems to be no compelling reason why this should occur – as Maginnis points out, one might expect that reliance on precedent would tend to lead to preservation or even precise imitation of pre-1348 styles: Maginnis, op cit at 173.

26. Ambrogio’s work was for the altar of the Duomo of Siena. Bartolo’s work was probably originally for an altar in Sant’ Agostino, San Gimignano.

27. Meiss, op cit at 19.

28. Wainwright, op cit at 187.

29. Harpring, op cit at 120.

30. Wainwright, op cit at 186.

31. Meiss, op cit at 56.

32. Meiss mentions the child only in passing, and claims to detect that the child is looking at the Priest. However, this would appear to be almost a physical impossibility.

33. Van Os’s view of Bartolo’s shortcomings also sits oddly with his later-expressed views as to the originality of the design of Bartolo’s altarpieces in provincial centres.

34. An excellent photographic representation of the cycle is in Freuler, G., Bartolo di Fredi Cini, Desertina Verlag, 1994 (back cover insert).

35. Meiss, op cit at 68.

36. Fengler, C K., “Bartolo de Fredi’s Old Testament frescoes in San Gimignano”, Art Bulletin 63, 1981, 374-384, at 378 and 384. Theoretically, Taddeo’s work could have been executed at any time before 1367, but to a large extent the date is irrelevant in view of his consistency of style over this period. Meiss refers to Taddeo’s work only in a footnote (68 fn 37), where he says that the same subject matter had been used by Taddeo, and tentatively suggesting that this work was started “in the ‘fifties?” (sic) and that it was completed some years later “by another painter”.

37. Meiss, op cit at 4, 56.

38. Fengler, op cit at 383.

39. Meiss, op cit at 46 fn 131.

40. Meiss, op cit at 7, 21. Vasari had also effectively dismissed Bartolo as a mediocrity: Gardner, J., Book Review, Burlington Magazine 139, no. 1132, 478-9.

41. Harpring, op cit at 9; Gardner, op cit at 478.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Surviving the Black Death", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to Home

2. Kelly, op cit, at 26.

3. Meiss, M., Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, Harper and Row 1973, at 66; Maginnis, H.B.J., Painting in the age of Giotto: a historical re-evaluation, University Park, 1997, at 191.

4. Norman, D, (ed) Siena, Florence and Padua: Art, Society and Religion 1280-1400, Vol 1, Yale University Press 1995, at 19.

5. Bowsky, W M, “The impact of the Black Death upon Sienese government and society”, Speculum 39, 1964, 1-34.

6. Bartolo was probably born in 1330 and died in 1410.

7. Meiss, op cit at 66.

8. Steinhoff, J., “Artistic Working Relationships after the Black Death: a Sienese compagnia”, Renaissance Studies 2000, 14, no. 1, 1-45, at 44.

9. Freuler, G., and Wainwright, V., Letter to Editor, Art Bulletin 68, 1986, 327-8.

10. In 1368, 1374 and 1389: Harpring, P, The Sienese Trecento Painter Bartolo di Fredi, Associated University Presses Inc, 1993, at 16.

11. Wainwright, V., “Andrea Vanni and Bartolo di Fredi: Sienese painters in their Social Context”, PhD diss, University of London, 1978, at 36.

12. Wainwright, op cit, at 10; Harpring, op cit at 16.

13. Freuler and Wainwright, op cit at 328.

14. Norman, D., “Change and continuity: art and religion after the Black Death” 177-196, in Norman, D., (ed) Siena, Florence and Padua: Art, Society and Religion 1280-1400, Vol 1, Yale University Press 1995, at 195.

15. A detailed study by Wainwright concluded that “on the whole, Sienese painters in the latter half of the Trecento do not appear to have been as adventurous as their illustrious predecessors; with few exceptions they were perhaps reluctant to undertake long and potentially hazardous journeys to work in other cities in the peninsula”: Wainwright, op cit at 162.

16. Wainwright, op cit, at 154.

17. Meiss, op cit at xi.

18. Maginnis, op cit at 164.

19. A detailed examination of this much disputed view is outside the scope of this article.

20. Maginnis, op cit at 164-191.

21. Van Os, H. W, “Tradition and innovation in some altarpieces by Bartolo di Fredi”, Art Bulletin 67, 1985, at 56, 64.

22. Steinhoff, op cit at 7. This view has been further developed in the same author's Sienese Painting after the Black Death: Artistic Pluralism, Politics and the New Art Market, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

23. Freuler and Wainwright, op cit at 327.

24. Norman, op cit at 195. Another reason may simply have been that the abundance of commissions, combined with the demands of his political career, led Bartolo into taking shortcuts.

25. There seems to be no compelling reason why this should occur – as Maginnis points out, one might expect that reliance on precedent would tend to lead to preservation or even precise imitation of pre-1348 styles: Maginnis, op cit at 173.

26. Ambrogio’s work was for the altar of the Duomo of Siena. Bartolo’s work was probably originally for an altar in Sant’ Agostino, San Gimignano.

27. Meiss, op cit at 19.

28. Wainwright, op cit at 187.

29. Harpring, op cit at 120.

30. Wainwright, op cit at 186.

31. Meiss, op cit at 56.

32. Meiss mentions the child only in passing, and claims to detect that the child is looking at the Priest. However, this would appear to be almost a physical impossibility.

33. Van Os’s view of Bartolo’s shortcomings also sits oddly with his later-expressed views as to the originality of the design of Bartolo’s altarpieces in provincial centres.

34. An excellent photographic representation of the cycle is in Freuler, G., Bartolo di Fredi Cini, Desertina Verlag, 1994 (back cover insert).

35. Meiss, op cit at 68.

36. Fengler, C K., “Bartolo de Fredi’s Old Testament frescoes in San Gimignano”, Art Bulletin 63, 1981, 374-384, at 378 and 384. Theoretically, Taddeo’s work could have been executed at any time before 1367, but to a large extent the date is irrelevant in view of his consistency of style over this period. Meiss refers to Taddeo’s work only in a footnote (68 fn 37), where he says that the same subject matter had been used by Taddeo, and tentatively suggesting that this work was started “in the ‘fifties?” (sic) and that it was completed some years later “by another painter”.

37. Meiss, op cit at 4, 56.

38. Fengler, op cit at 383.

39. Meiss, op cit at 46 fn 131.

40. Meiss, op cit at 7, 21. Vasari had also effectively dismissed Bartolo as a mediocrity: Gardner, J., Book Review, Burlington Magazine 139, no. 1132, 478-9.

41. Harpring, op cit at 9; Gardner, op cit at 478.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Surviving the Black Death", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to Home