Bruegel’s Peasant Wedding Feast

The case of the missing bridegroom and other puzzles

By Philip McCouat For comments on this article see here

A lively celebration of a marriage

|

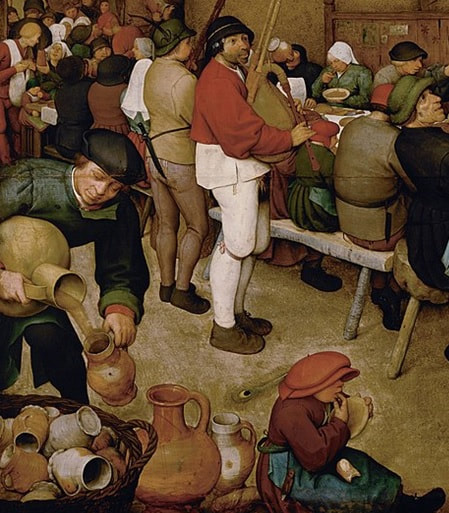

The Peasant Wedding Feast, a painting by Pieter Bruegel in 1567, was one of the last paintings he ever created. It is also one of his most popular and well-recognised works [1]. Bruegel invites the viewer to witness a convivial and lively celebration of a marriage, seduces them with his warm, approachable colours of red, yellow orange [2], and leaves them with the feeling that they have been given a genuine insight into how ordinary people really lived in the 16th century Netherlands. |

More on Bruegel at

|

Fig 1: Pieter Bruegel, Peasant Wedding Feast (1567), 114 x 163 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Fig 1: Pieter Bruegel, Peasant Wedding Feast (1567), 114 x 163 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Breugel was, of course, famous for his interest in depicting peasant life. According to his first biographer, Karel van Mander, Bruegel enjoyed going out with a friend to "village fairs or weddings, wearing peasant garb. They came to the wedding bearing gifts like everyone else and claiming to be members of the family of the bride or groom. Bruegel took pleasure in studying the appearance of the peasants . . . He also knew how to represent these peasant men and women most exactly" [3].

However, despite Bruegel’s apparent mastery of the genre (or possibly because of it), this particular painting conceals a number of mysteries, which critics over the last 100 years have almost been falling over themselves (and each other) in their eagerness to solve. In this article, we’ll attempt to analyse what’s happening in the painting, and see if we can throw some light on these mysteries which have caused so much confusion.

Part 1: DESCRIPTION

However, despite Bruegel’s apparent mastery of the genre (or possibly because of it), this particular painting conceals a number of mysteries, which critics over the last 100 years have almost been falling over themselves (and each other) in their eagerness to solve. In this article, we’ll attempt to analyse what’s happening in the painting, and see if we can throw some light on these mysteries which have caused so much confusion.

Part 1: DESCRIPTION

sETTING THE SCENE

Let us set the scene. On an autumn day in a 16th century Flemish village, a wedding is being celebrated with a feast in a barn. At a long trestle table, slanting away from the viewer, sit the invited guests, eating, drinking and chatting. On the yellow back wall – really, neatly trimmed bales of hay – hang the crossed sheaves of grain secured by a rake, a common sign of autumn harvest celebrations and fertility; clearly, the harvest has been good [4]. In pride of place, just to right of centre, sits the bride; above her, the traditional wedding crown hangs from the dark green cloth attached to the wall.

In the right foreground (Fig 2), two servants carry a tray fashioned from a detached door still bearing its hinges, with servings of soup or a yellow porridge in flat bowls. The servants have lowered the tray to enable another man to reach out and -- rather precariously! -- transfer the bowls to the table, to add to the tankards and bread already there.

In the right foreground (Fig 2), two servants carry a tray fashioned from a detached door still bearing its hinges, with servings of soup or a yellow porridge in flat bowls. The servants have lowered the tray to enable another man to reach out and -- rather precariously! -- transfer the bowls to the table, to add to the tankards and bread already there.

The solidly-built servant with a blue top and white apron, right in the centre of the painting, serves to anchor it -- after initially being drawn to him, the eye travels straight on to the “enthroned” bride, to the left for two bagpipers and to the right for the other servant. This sense of “being there” is reinforced by the painting’s low perspective, seemingly showing the scene from the same angle as a standing viewer [5].

Over to the left, two bagpipers are providing the music for the occasion (Fig 3). Their pipes (pijpzak) are decorated with a bunch of white ribbons [nesteln) – also evident on the white-aproned servant’s hat – variously interpreted as a typical wedding adornment [6], or as indicating membership of a young men’s group [7]. Coins, just visible, hang from the red-coated piper’s hat. These may relate to membership of a musicians’ guild [8] or, alternatively, may have come from the bride’s shoes, a custom that has carried over in some cultures into present times [9].

Over to the left, two bagpipers are providing the music for the occasion (Fig 3). Their pipes (pijpzak) are decorated with a bunch of white ribbons [nesteln) – also evident on the white-aproned servant’s hat – variously interpreted as a typical wedding adornment [6], or as indicating membership of a young men’s group [7]. Coins, just visible, hang from the red-coated piper’s hat. These may relate to membership of a musicians’ guild [8] or, alternatively, may have come from the bride’s shoes, a custom that has carried over in some cultures into present times [9].

In the left foreground, a man is pouring beer from a clay pitcher into smaller jugs, and a young child – too young to have qualified for wearing breeches -- sits on the floor, licking food off his fingers, with a peacock feather in his hat.

Off in the top left corner, a crowd of locals have gathered inside the barn’s doorway, maybe just to see what’s happening or to share in the drinking. Their exclusion from the table probably reflects the Imperial regulations that limited the number of wedding guests to twenty [10].

Off in the top left corner, a crowd of locals have gathered inside the barn’s doorway, maybe just to see what’s happening or to share in the drinking. Their exclusion from the table probably reflects the Imperial regulations that limited the number of wedding guests to twenty [10].

Who’s who, and where’s the bridegroom?

We’ve already noted the bride (Fig 2). She sits quietly, not conversing with anyone but smiling faintly, her cheeks flushed, her eyes half-closed, her hands clasped demurely before her on the table. Instead of the hat that everyone else in the painting is wearing, she wears a simple wedding tiara, interleaved with flowers, suggesting virginity. Her long auburn hair hangs loose; from now onwards her hair will be cut and confined, as befitting a married woman. Her passivity is understandable – it was custom for the bride to do nothing on her wedding day; it was “at least one holiday in a lifetime of hard labour” [11].

At the far right of the table, a brown-cowled Franciscan monk is gesturing and talking intently with a prosperous-looking older man who is sitting on an upturned barrel. The monk is there probably to confer a religious blessing for the marriage; the older man is possibly the local landowner. Next to him, a dog pokes his face out from under the table, to nose some food scraps that have been left on an empty part of the bench.

Where then is the bridegroom? He is not sitting next to his betrothed; she has women on both sides of her (you can only just see the white headdress of the one on the bride’s right, possibly her mother). According to some sources, there was a custom for the bridegroom not to actually attend the wedding feast at all – or rather not attend before dark. Another claimed custom was that he had to attend but also had to assist in the serving of the food and drink [12]. On that basis, he could be the man pouring the beer in the bottom left corner; and his normal seat could possibly be the unoccupied place on the bench at the end of the table at right. Or he might be the red-capped man twisting round to takes the plates of food from the tray. Or he may be the white aproned man carrying the table-tray in the foreground, whose face is compositionally linked to the bride’s face [13].

Yet another view [14] is based on people’s supposed facial similarities, position at the table, and mode of dress. So, it is said that the bride bears a physical resemblance to the beer-pouring man, and also to the two servants, so all three may be the bride’s brothers. On this view, the older woman sitting on the bride’s left (the viewer’s right) and the well-dressed man in the high-backed chair next to her are the bride’s parents-in-law, as they both have no resemblance to her and are rather better dressed. As a matter of elimination, on this theory, the bridegroom is the distinctively-featured, dark-clad man sitting on the near side of the table, seeming to hold up his tankard for a refill. This view is supported by the claimed fact that this man and his parents all wear city clothes, unlike everyone else; apparently, this mixture of town and country was not unusual in an area which was enjoying relative prosperity [15].

Of course, it wouldn’t be a Bruegel painting if all the critics agreed! The couple sitting next to the bride have also been interpreted as her parents, not her parents-in law [16]. Yet another well-supported interpretation is that the man sitting in the high-backed chair is the notary who has solemnised the wedding, not the bride’s father or father-in-law [17].

At the far right of the table, a brown-cowled Franciscan monk is gesturing and talking intently with a prosperous-looking older man who is sitting on an upturned barrel. The monk is there probably to confer a religious blessing for the marriage; the older man is possibly the local landowner. Next to him, a dog pokes his face out from under the table, to nose some food scraps that have been left on an empty part of the bench.

Where then is the bridegroom? He is not sitting next to his betrothed; she has women on both sides of her (you can only just see the white headdress of the one on the bride’s right, possibly her mother). According to some sources, there was a custom for the bridegroom not to actually attend the wedding feast at all – or rather not attend before dark. Another claimed custom was that he had to attend but also had to assist in the serving of the food and drink [12]. On that basis, he could be the man pouring the beer in the bottom left corner; and his normal seat could possibly be the unoccupied place on the bench at the end of the table at right. Or he might be the red-capped man twisting round to takes the plates of food from the tray. Or he may be the white aproned man carrying the table-tray in the foreground, whose face is compositionally linked to the bride’s face [13].

Yet another view [14] is based on people’s supposed facial similarities, position at the table, and mode of dress. So, it is said that the bride bears a physical resemblance to the beer-pouring man, and also to the two servants, so all three may be the bride’s brothers. On this view, the older woman sitting on the bride’s left (the viewer’s right) and the well-dressed man in the high-backed chair next to her are the bride’s parents-in-law, as they both have no resemblance to her and are rather better dressed. As a matter of elimination, on this theory, the bridegroom is the distinctively-featured, dark-clad man sitting on the near side of the table, seeming to hold up his tankard for a refill. This view is supported by the claimed fact that this man and his parents all wear city clothes, unlike everyone else; apparently, this mixture of town and country was not unusual in an area which was enjoying relative prosperity [15].

Of course, it wouldn’t be a Bruegel painting if all the critics agreed! The couple sitting next to the bride have also been interpreted as her parents, not her parents-in law [16]. Yet another well-supported interpretation is that the man sitting in the high-backed chair is the notary who has solemnised the wedding, not the bride’s father or father-in-law [17].

The mystery of the third foot

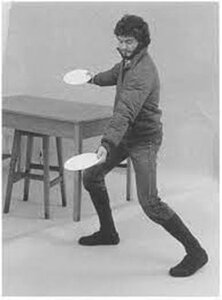

From discussing someone who seems to have been misplaced, we now pass to something that seems to have been added. Look at the red-clad servant on the right carrying the tray, and the man twisting to pass the plates to the table (Fig 4). Most viewers assume that the twisting man is sitting, that the dark brown patch underneath his arm is his left leg, and that his foot visible under the tray (circled in yellow) is his left foot. Viewers are then left with the conundrum that Bruegel seems to have given the red-clad servant three feet (the third foot is circled red).

Is this a joke by the painter? Or a huge error? Clearly, Bruegel’s son, Brueghel the Younger, thought it was an error or, at best, too confusing for viewers. His 1620 copy of his father’s painting solves the problem simply by eliminating the third foot altogether (Fig 5).

However, it seems that we may have been looking at Bruegel's painting incorrectly. A detailed consideration by Claudine Majzels of the angles and the relative positions of the people involved suggests that we need to accept that the twisting man is not sitting, but standing with knees bent, and the brown-clad leg and the foot circled yellow in Fig 4 are actually his right leg and foot [18]. The mysterious third foot is then explicable as his extended left foot. The position is explained in Majzels’ re-enactment and diagram (Figs 6 and 7).

Part II: INTERPRETATION

Moral lesson or early journalism?

As with many Bruegel paintings, opinion is split on whether he was merely depicting a scene here, or poking fun at rustic ways [19], or giving us a moral lecture by illustrating the depravity of sin. Personally, I suspect that there may be elements of all these factors present in the painting, to a greater or lesser extent.

Take, for example, the argument that Wedding Feast is a sermon condemning gluttony and other sins [20]. Such a view relies on aspects such as the pile of beer jugs in the wicker basket in the lower left corner (Fig 3), and the emphasis on consumption -- with the cooking spoon in the lead servant’s hat being a regarded as a symbol of gluttony [21] and the child’s peacock feather being taken as a symbol of sinful pride [22]. However, on its face, the scene hardly seems to be bawdy or bacchanalian and, considering that it is a country wedding feast, quite civilised and restrained. Wied comments, for example, that “it is doubtful whether things could possibly be more modest and well-behaved at a peasant wedding” [23].

Commentator Timothy Foote argues that it is this very aspect -- the depiction of the life of the common person as a subject for its own sake, with little ulterior moral or religious motive -- that makes this painting “one of the pioneering peaks of Bruegel’s creative lifetime”. He concludes that the painting is among “the most straightforward and natural renderings of everyday life painted in the 16th century” [24]. Indeed, Oberthaler comments that “for the first time in the history of art, Bruegel gives the genre scene a scale that can be measured against classical models” [25].

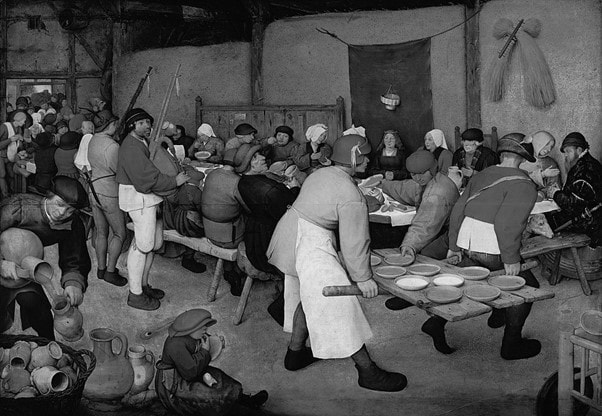

Just for a moment, let’s try to forget that it’s a painting. Here it is in black and white (Fig 8). Can you almost imagine it’s a photograph of an actual scene? In saying this, of course, I’m not suggesting that the painting is photorealistic, far from it. But it suggests that Bruegel here is giving the impression that he is painting from actual experience, and that he (and through him, the viewer) could actually be in that barn watching what was going on. In effect, then, the painting is playing a role that is analogous to a modern-day photograph of the occasion.

Take, for example, the argument that Wedding Feast is a sermon condemning gluttony and other sins [20]. Such a view relies on aspects such as the pile of beer jugs in the wicker basket in the lower left corner (Fig 3), and the emphasis on consumption -- with the cooking spoon in the lead servant’s hat being a regarded as a symbol of gluttony [21] and the child’s peacock feather being taken as a symbol of sinful pride [22]. However, on its face, the scene hardly seems to be bawdy or bacchanalian and, considering that it is a country wedding feast, quite civilised and restrained. Wied comments, for example, that “it is doubtful whether things could possibly be more modest and well-behaved at a peasant wedding” [23].

Commentator Timothy Foote argues that it is this very aspect -- the depiction of the life of the common person as a subject for its own sake, with little ulterior moral or religious motive -- that makes this painting “one of the pioneering peaks of Bruegel’s creative lifetime”. He concludes that the painting is among “the most straightforward and natural renderings of everyday life painted in the 16th century” [24]. Indeed, Oberthaler comments that “for the first time in the history of art, Bruegel gives the genre scene a scale that can be measured against classical models” [25].

Just for a moment, let’s try to forget that it’s a painting. Here it is in black and white (Fig 8). Can you almost imagine it’s a photograph of an actual scene? In saying this, of course, I’m not suggesting that the painting is photorealistic, far from it. But it suggests that Bruegel here is giving the impression that he is painting from actual experience, and that he (and through him, the viewer) could actually be in that barn watching what was going on. In effect, then, the painting is playing a role that is analogous to a modern-day photograph of the occasion.

But there’s another twist. Not everything is as it seems. Recent investigations have revealed that the impression of the painting’s moderation may need some qualification. Two new pieces of evidence have emerged which suggest that the painting that we see today may actually be a sanitised version of the much more bawdy painting that Bruegel originally created. It is to this issue that we now turn.

The affair of the missing codpiece

The first piece of evidence relates to the red-coated bagpiper, standing just left of centre. He is looking to the right to watch the servants carrying the tray. Maybe he’s just realised he’s hungry. However, there is an odd thing about him. Look at this detail from the 1620 copy of the painting by Pieter Brueghel the Younger (Fig 9); the bagpiper here is wearing an extremely prominent and commodious codpiece [26]. This does not appear at all in Bruegel senior's painting; instead of a codpiece, there is simply a flat black patch (Fig 10).

So, was the prominent codpiece just a pure invention by the Younger, trying to make the painting more titillating to viewers? Not at all. Because infrared photography indicates that Bruegel senior had also included just such a codpiece in his painting, but that it was later painted out – either by Bruegel as a second thought during the painting process, or at some later stage, by Bruegel or someone else, after the painting had been finished, possibly at the request of the private patron who commissioned the work [27].

This type of censorship of Bruegel’s paintings was not unknown. In his Bruegel’s notably more earthy The Wedding Dance (1566) [28], the prominent codpieces depicted were also overpainted at some stage, and only became visible again in 1941, when the painting’s authentic surface was restored [29].

Clearly then, the codpieces painted by Breughel the Younger were no invention. Either they were still present in the original when he made his copy, or at least known to him in the form of prints that were made of the original, or even possibly from preliminary sketches done by his father that survived.

This type of censorship of Bruegel’s paintings was not unknown. In his Bruegel’s notably more earthy The Wedding Dance (1566) [28], the prominent codpieces depicted were also overpainted at some stage, and only became visible again in 1941, when the painting’s authentic surface was restored [29].

Clearly then, the codpieces painted by Breughel the Younger were no invention. Either they were still present in the original when he made his copy, or at least known to him in the form of prints that were made of the original, or even possibly from preliminary sketches done by his father that survived.

The puzzle of the amorous couple

The second piece of evidence as to Bruegel’s intent also involves the bagpipers, though indirectly. You’ll notice that the pipes on each bagpiper’s instrument point upwards, directing our eyes towards the dark area above the hay in the top left corner (see Fig 1). But there appears to be nothing in particular there, other than the faint outline of a ladder. However, if we look again at Breughel the Younger’s later copy (Fig 11), we can just see a couple amorously entwined together, unnoticed by the wedding party, lying in the shadows there.

This raises the same issue as arose with the codpiece. And again, as with the codpiece, infrared photography suggests that the same couple also actually appeared in Bruegel senior’s original painting, but have been painted out [30].

Effectively, then, Bruegel’s original has been sanitised by the removal of two "bawdy" features which were considered later to be unsuitable. The fact that the original painting had a greater emphasis on sin than appears today means that our initial impression that the painting was quite decorous may, to that extent, need to be modified.

Effectively, then, Bruegel’s original has been sanitised by the removal of two "bawdy" features which were considered later to be unsuitable. The fact that the original painting had a greater emphasis on sin than appears today means that our initial impression that the painting was quite decorous may, to that extent, need to be modified.

The attraction of mystery

This painting is like a detective story, containing ambiguous clues and sudden unexpected twists. But there is no neat conclusion in which all the loose ends are tied up. We may have worked out who owns the third foot, but we still don’t really know where the bridegroom is. And are the now-missing codpiece and kissing couple just honest slices of life? Or were they originally intended to make the painting more titillating or amusing? Or, contrarily, were these suggestions of sinful activity intended to indicate that Bruegel was actually giving us a moral message? As with many of his paintings, Bruegel keeps us guessing. And, centuries later, it may be that this is part of his appeal.

© Philip McCouat 2021. First published September 2021.

This article may be cited as “Bruegel’s Peasant Wedding Feast: the case of the missing bridegroom and other mysteries”, Journal of Art in Society (2021) www.artinsociety.com

Your comments on this article are welcome.

RETURN TO HOME

© Philip McCouat 2021. First published September 2021.

This article may be cited as “Bruegel’s Peasant Wedding Feast: the case of the missing bridegroom and other mysteries”, Journal of Art in Society (2021) www.artinsociety.com

Your comments on this article are welcome.

RETURN TO HOME

end notes

1. The painting is also known as Peasant Wedding

2. it is possible that some of the browns may originally have been bluer. This fading could have happened if Bruegel used smalt, a violet blue pigment that was popular at the time, but later discovered to be unstable and given to breaking down: Nancy Kenney, “Science illuminates art in Detroit’s celebration of Bruegel’s The Wedding Dance, The Art Newspaper, 10 December 2019 https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/science-illuminates-art-in-detroit-s-celebration-of-bruegel-s-wedding-dance

3. Karel van Mander, Schilder-boek (1604)

4. Alpers, Svetlana. "Bruegel's Festive Peasants" in Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 6, no. 3/4 (1972) at 167. Accessed July 12, 2021. doi:10.2307/3780341.

5. Elke Oberthaler and others, Bruegel the Master. Thames & Hudson (2018) at 262

6. Alpers, op cit at 165; Oberthaler, op cit at 261

7. Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, “The barn is full – time for a wedding!”, in What Great Paintings Say, Vol 1, Taschen, Koln, 2003 at 177

8. Oberthaler, op cit at 265

9. Alpers, op cit at 167

10. Oberthaler, op cit at 265

11. Hagen, op cit at 181

12. Alpers, op cit at 168

13. Oberthaler, op cit at 261

14. Timothy Foote and eds, The World of Bruegel, Time Life International (Nederland) 1971 at 135, citing Gilbert Highet

15. Yet another view is that the bridegroom is the somewhat befuddled-looking man sitting at the table, eating with a spoon, three to the bride’s right

16. See for example, Alexander Wied, Bruegel, Bay Books, Sydney, 1979, at 173

17. See for example Hagen, op cit at 177

18. Claudine Majzels, "The Man with Three Feet in Pieter Bruegel the Elder's Peasant Wedding", Canadian Art Review 27, No 1/2 (2000) 46

19. Walter S Gibson, “Some notes on Pieter Bruegel’s Peasant Wedding Feast”, Art Quarterly 28 (1965) 196; Pieter Bruegel and the Art of Laughter, University of California Press, 2006

20. It has also been argued that the painting is an allegory of the church abandoned by Christ, or that the work is Bruegel’s version of the Last Supper, or that it refers to the biblical marriage at Cana, where Christ turned water into wine and vessels were perpetually filled up; see Hagen, op cit at 177

21. The spoon has alternatively been interpreted as a symbol of poverty: Hagen, op cit at 179. A similar spoon appears in the hat of the main male dancer in Bruegel’s Peasant Dance (1568)

22. A similar feather appears on the hat of the man sitting next to the bagpiper in Bruegel’s Peasant Dance (1568)

23. Wied, op cit at 174

24. Foote, op cit at 114

25. Oberthaler, op cit at 262

26. Codpieces emerged to solve the problem that men’s tights simply went to the top of the leg, and did not cover the groin

27. Oberthaler, op cit at 262; TM Richardson, Pieter Bruegel the Elder: art discourse in the sixteenth-century Netherlands, Doctoral Thesis, 2007 Leiden University Scholarly Publications at 91 (fig 31)

28. Also known as Peasant Wedding Dance

29. Kenney, op cit

30. Oberthaler, op cit at 262; Richardson, op cit at 91 (fig 32).

© Philip McCouat 2021

RETURN TO HOME

2. it is possible that some of the browns may originally have been bluer. This fading could have happened if Bruegel used smalt, a violet blue pigment that was popular at the time, but later discovered to be unstable and given to breaking down: Nancy Kenney, “Science illuminates art in Detroit’s celebration of Bruegel’s The Wedding Dance, The Art Newspaper, 10 December 2019 https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/science-illuminates-art-in-detroit-s-celebration-of-bruegel-s-wedding-dance

3. Karel van Mander, Schilder-boek (1604)

4. Alpers, Svetlana. "Bruegel's Festive Peasants" in Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 6, no. 3/4 (1972) at 167. Accessed July 12, 2021. doi:10.2307/3780341.

5. Elke Oberthaler and others, Bruegel the Master. Thames & Hudson (2018) at 262

6. Alpers, op cit at 165; Oberthaler, op cit at 261

7. Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, “The barn is full – time for a wedding!”, in What Great Paintings Say, Vol 1, Taschen, Koln, 2003 at 177

8. Oberthaler, op cit at 265

9. Alpers, op cit at 167

10. Oberthaler, op cit at 265

11. Hagen, op cit at 181

12. Alpers, op cit at 168

13. Oberthaler, op cit at 261

14. Timothy Foote and eds, The World of Bruegel, Time Life International (Nederland) 1971 at 135, citing Gilbert Highet

15. Yet another view is that the bridegroom is the somewhat befuddled-looking man sitting at the table, eating with a spoon, three to the bride’s right

16. See for example, Alexander Wied, Bruegel, Bay Books, Sydney, 1979, at 173

17. See for example Hagen, op cit at 177

18. Claudine Majzels, "The Man with Three Feet in Pieter Bruegel the Elder's Peasant Wedding", Canadian Art Review 27, No 1/2 (2000) 46

19. Walter S Gibson, “Some notes on Pieter Bruegel’s Peasant Wedding Feast”, Art Quarterly 28 (1965) 196; Pieter Bruegel and the Art of Laughter, University of California Press, 2006

20. It has also been argued that the painting is an allegory of the church abandoned by Christ, or that the work is Bruegel’s version of the Last Supper, or that it refers to the biblical marriage at Cana, where Christ turned water into wine and vessels were perpetually filled up; see Hagen, op cit at 177

21. The spoon has alternatively been interpreted as a symbol of poverty: Hagen, op cit at 179. A similar spoon appears in the hat of the main male dancer in Bruegel’s Peasant Dance (1568)

22. A similar feather appears on the hat of the man sitting next to the bagpiper in Bruegel’s Peasant Dance (1568)

23. Wied, op cit at 174

24. Foote, op cit at 114

25. Oberthaler, op cit at 262

26. Codpieces emerged to solve the problem that men’s tights simply went to the top of the leg, and did not cover the groin

27. Oberthaler, op cit at 262; TM Richardson, Pieter Bruegel the Elder: art discourse in the sixteenth-century Netherlands, Doctoral Thesis, 2007 Leiden University Scholarly Publications at 91 (fig 31)

28. Also known as Peasant Wedding Dance

29. Kenney, op cit

30. Oberthaler, op cit at 262; Richardson, op cit at 91 (fig 32).

© Philip McCouat 2021

RETURN TO HOME