The Art of Shadows

By Philip McCouat For readers’ comments on this article, see here

introduction

Shadows are strange. It can take years for children to fully understand how their own shadows are formed, or why they vary as the child moves around [1]. Yet we cannot escape them, for we all live in a world of shadows. Everyone has their own ever-changing personal shadow that accompanies them from the time they are born. Depending on the absence or presence of light, this shadow can disappear, then magically appear. You can’t hold it, and it constantly changes shape. Sometimes it resembles you, but at other times it is magnified or diminished. It is utterly personal to you, but totally impersonal in its behaviour.

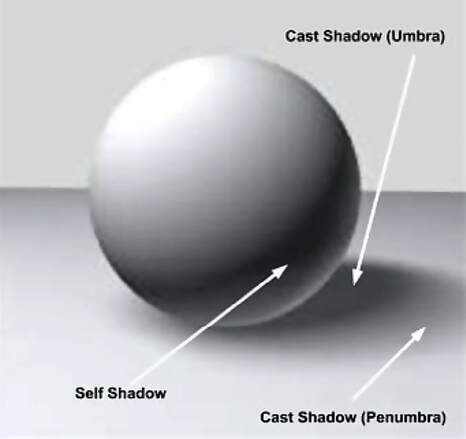

In this article, we are dealing primarily with cast shadows. These are the type of shadow that we normally mean when we are talking about personal shadows, or the shadow of a building or tree. A cast shadow occurs where an object is lit by a light source, such as the sun, a candle or an electric light. A shadow of the object will appear (or “be cast”) on the ground or surroundings to the side of the object that is hidden from the light source. Where there is more than one source of light, or a light from a relatively wide range, the innermost parts of the cast shadow (“umbra”) may be darker than the outermost parts of the shadow (“penumbra”) [2].

There are of course other types of shadow, such as shadows formed on the lit object itself, primarily on its surface hidden from the light source; these are variously described as “self” or “form” shadows. The relationship between cast shadows and self shadows is illustrated below.

In this article, we are dealing primarily with cast shadows. These are the type of shadow that we normally mean when we are talking about personal shadows, or the shadow of a building or tree. A cast shadow occurs where an object is lit by a light source, such as the sun, a candle or an electric light. A shadow of the object will appear (or “be cast”) on the ground or surroundings to the side of the object that is hidden from the light source. Where there is more than one source of light, or a light from a relatively wide range, the innermost parts of the cast shadow (“umbra”) may be darker than the outermost parts of the shadow (“penumbra”) [2].

There are of course other types of shadow, such as shadows formed on the lit object itself, primarily on its surface hidden from the light source; these are variously described as “self” or “form” shadows. The relationship between cast shadows and self shadows is illustrated below.

We’ll be dealing here with the many, often-overlooked, ways in these cast shadows have played a role in Western art, primarily in painting. Though some mention of the impact on the art of other areas is also made where appropriate, this article does not attempt to examine the finer technical points of degrees of shading and perspective.

Part 1: Early use of shadows

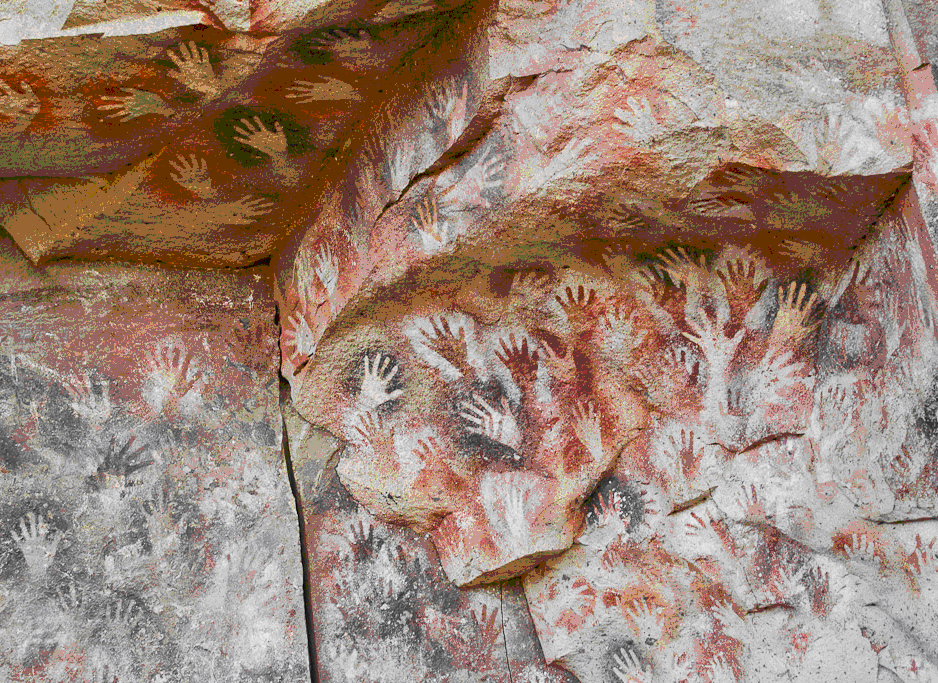

Shadows have been used in art for thousands of years. The Cave of Hands in Patagonia has images of hundreds of outstretched hands, stencilled onto cave walls up to 7,000 years ago. These were formed by using a pipe to spray or blow pigment to trace the outline of a hand placed flat against the cave wall. In this case, of course, the aim was to depict the hand, not the shadow, which is hidden from sight, but is identical to the shape as the hand itself [3]..

Thousands of years later, in the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, mentions the legend that painting began with the outlining of a man’s shadow cast on a wall. This process differs from the cave stencils ~ first, the shadow is not hidden (as it is with a stencilled hand) and is the main focus of the drawing; and second, the shape is defined by light, not a spray of pigment [4].

The legend has itself been depicted in many artworks from the 17th century onwards, including in this painting by Murillo.

The legend has itself been depicted in many artworks from the 17th century onwards, including in this painting by Murillo.

Whatever the truth of the legend, the depiction of cast shadows was certainly known to artists in antiquity, dating at least back to ancient Roman times. This is evident particularly in Roman mosaics. In Fig 4, we see objects lit by light coming from the left, resulting in cast shadows on the right-hand side. In Fig 5 we see a particularly subtle use of cast shadow – even the mouse’s tail is included; and in Fig 6, the cast shadows of Roman gladiators.

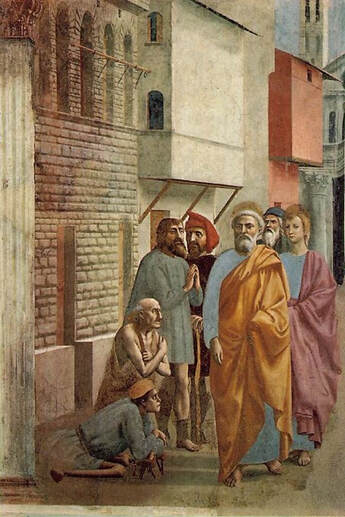

However, in the centuries after the Roman era, shadows ceased to be a factor in Western art. Medieval painting was not concerned with presenting reality, and used generalised light over the whole painting. Shadows therefore became essentially irrelevant. They did not make their first significant re-appearance until the early 15th century, as Western artists started to place much more emphasis on depicting reality. The Florentine artist Masaccio was an early adopter, with a painting that could hardly convey its meaning at all without depicting a shadow. This painting depicts the Biblical story of how St Peter miraculously cured a crippled man, not by touching him, but with St Peter’s own shadow [5]. The shadow here performs a dual role -- not only as a miraculous curative power, but also as a device to make the painting itself look more realistic.

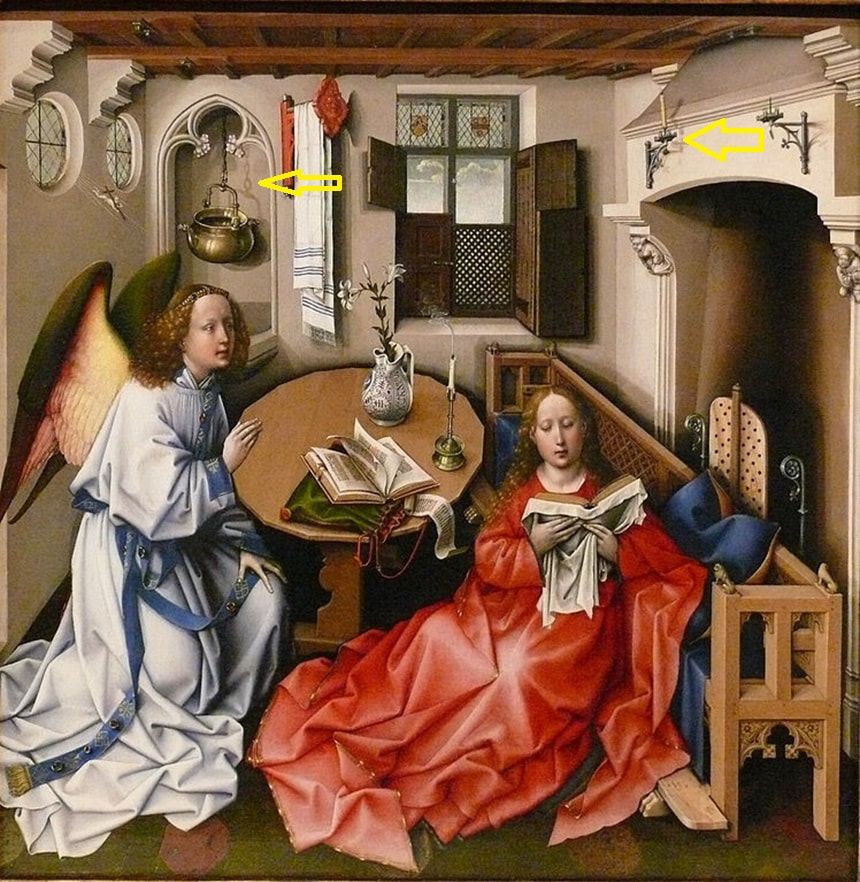

Cast shadows of objects, not just of people, also started to re-appear, particularly in the works of Flemish painters such as Robert Campin. In Fig 8, note the subtlety of the shadows cast by the cauldron in the niche, and the light fittings over the fireplace [6].

Part 2: How cast shadows are used

Having seen how cast shadows re-entered the world of art, we can turn to the various ways in which they have been used to achieve an artistic effect.

#1 Depth, perspective, realism

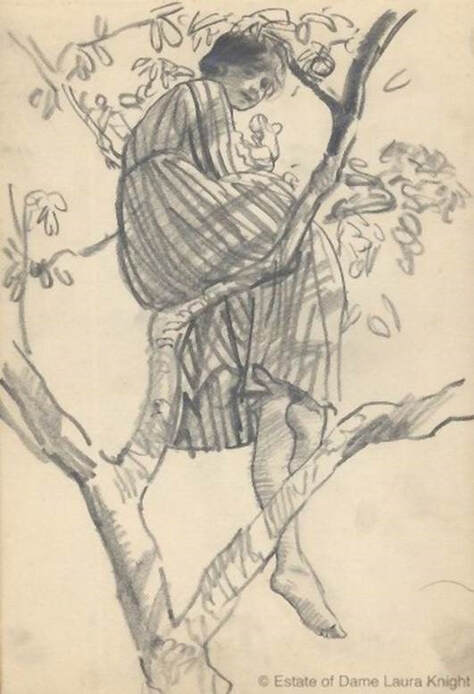

Shadows play an important role in grounding an image, in providing depth and perspective, and in defining the form and shape of the objects depicted. This is particularly important where the realism of images is important to the artist. A good example is provided by the shadow cast by of a flask of red wine on a tabletop in this detail from Caravaggio’s Bacchus (Fig 9) -- the shadow effectively anchors the flask on the table. Note too how Caravaggio has demonstrated his powers of observation by depicting the lighter part in the shadow’s penumbra. Equally instructive, though radically different in style and subject matter, is this sketch by Laura Knight, highlighting the shadows cast by the branches on the young woman’s face, legs and dress (Fig 10).

#1 Depth, perspective, realism

Shadows play an important role in grounding an image, in providing depth and perspective, and in defining the form and shape of the objects depicted. This is particularly important where the realism of images is important to the artist. A good example is provided by the shadow cast by of a flask of red wine on a tabletop in this detail from Caravaggio’s Bacchus (Fig 9) -- the shadow effectively anchors the flask on the table. Note too how Caravaggio has demonstrated his powers of observation by depicting the lighter part in the shadow’s penumbra. Equally instructive, though radically different in style and subject matter, is this sketch by Laura Knight, highlighting the shadows cast by the branches on the young woman’s face, legs and dress (Fig 10).

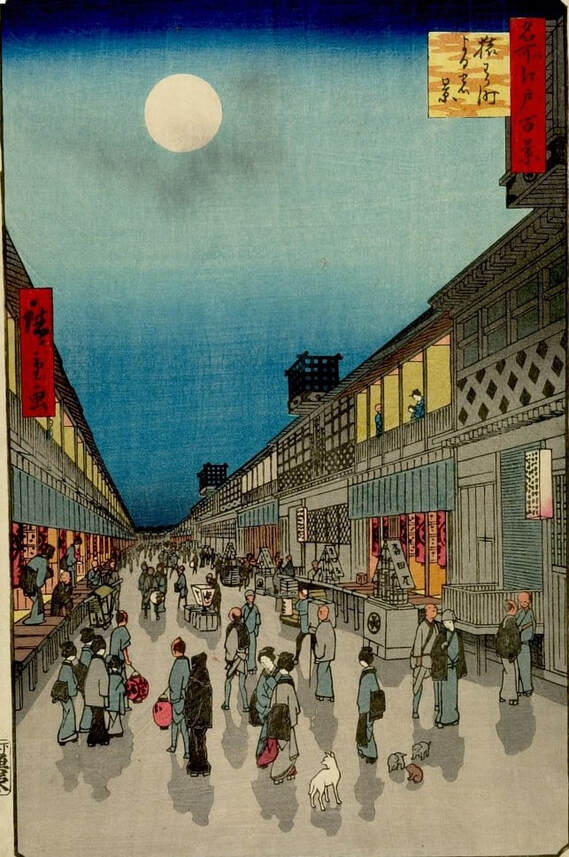

When using shadows in this way, of course, care must be taken to ensure that the shadow itself meets the requirements of perspective. Japanese woodblock prints traditionally do not emphasise depth, and do not feature many cast shadows, though there are exceptions, mainly of buildings or trees. When Utagawa Hiroshige, a leading Japanese woodblock print specialist, innovatingly incorporated shadows cast by people walking up a moonlit street towards a far horizon, he was meticulous in depicting Western-type perspective in the buildings lining the street, but it seems he failed to realise that the shadows of the people also needed to reflect that perspective, instead of all falling vertically (Fig 11). In reality, perspective would require that the shadows of people on either side of the street should slant away from the viewer, as in Fig 12.

The source of light can also affect the subject matter of the painting for a different, very practical reason. For a right-handed painter, a light source from the right may mean that their right hand may cast a shadow on the canvas. The same applies for a left-handed painter with a light source from the left. This is sometimes actually depicted in paintings showing an artist working at a canvas.

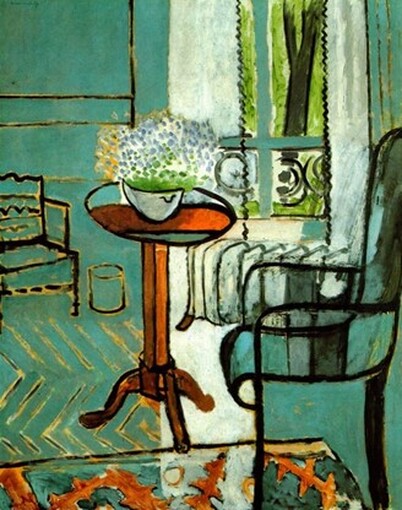

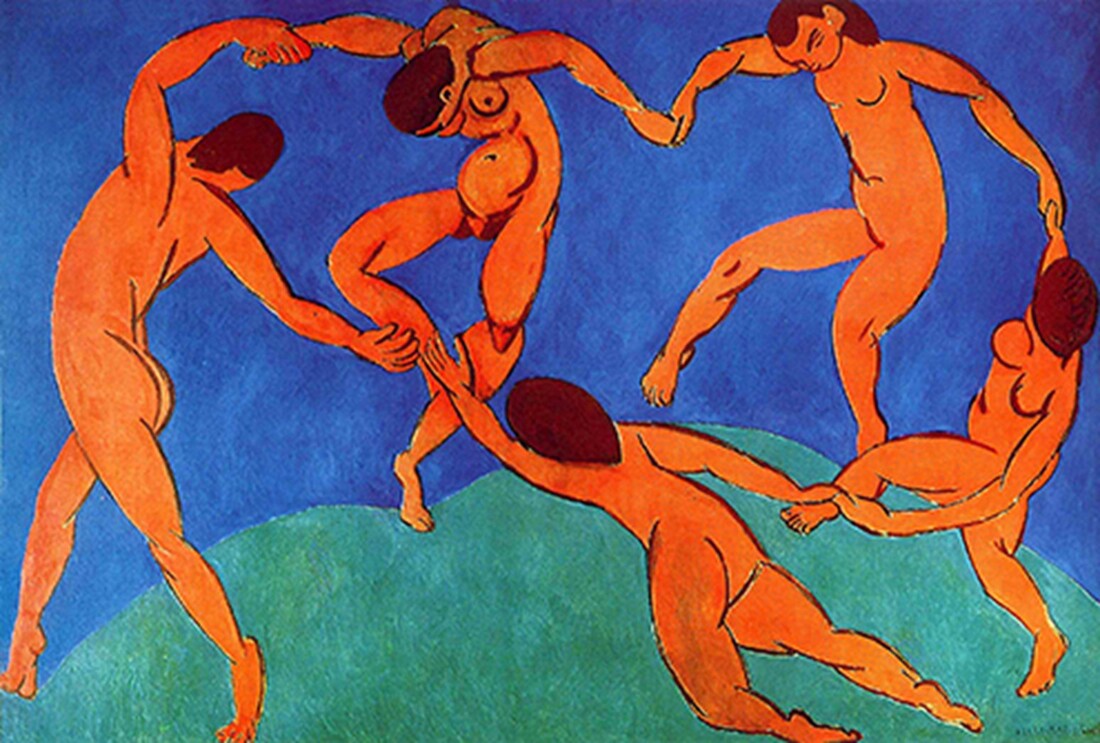

The absence of shadows, deliberate or otherwise, can make objects sometimes appear to be floating above the ground. This occurs in this painting by Matisse, an artist who favoured flat images and colour effects, and was less concerned with depicting depth or literal reality (Fig 14). This floating effect is used to good effect when depicting people who are dancing about, in Matisse’s The Dance (Fig 15).

#2 Telling a story

Shadows can help us understand what story an artist is trying to tell us.

Shadows lengthen as the light source gets lower or as the object moves further away from it. So, they can be used, for example, to enable us to identify whether the action of the painting takes place at sunrise, sunset or the middle of the day (see Fig 12). A hard bright light will produce a cast shadow with a sharp edge, whereas a soft light will produce a cast shadow with a more blurry edge.

Shadows can help us understand what story an artist is trying to tell us.

Shadows lengthen as the light source gets lower or as the object moves further away from it. So, they can be used, for example, to enable us to identify whether the action of the painting takes place at sunrise, sunset or the middle of the day (see Fig 12). A hard bright light will produce a cast shadow with a sharp edge, whereas a soft light will produce a cast shadow with a more blurry edge.

|

If we don’t know where a light source is, or what colour the light is, this can affect our perception of the colour of an object, because the perceived colour of it is affected by our perception of how it is lit. This is illustrated by the well-known example of the photograph of a dress that appears blue and black to some, but white and gold by others (Fig 16). The key is that for many people (including me), their brains interpret the blue as if it were a white in shadow, and the black as if it were a gold in shadow [7].

|

Cast shadows can reveal or emphasise other aspects of a painting. For example, heavy shadows cast on the countryside enhance the intended feeling of wide vistas in this landscape by Ruisdael [8]; and in a painting of an interior, deep shadows can be used to highlight the areas which are bathed in light.

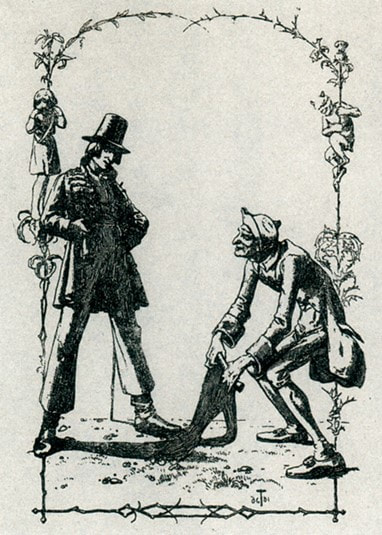

Cast shadows can also play a role in indicating the character of people in the painting. In the 18th century, Johann Caspar Lavater believed that one could discern the character of a person from their exact silhouette or profile outline, and this view was quite influential [9]. Taking this idea one (absurd) step further, JJ Grandville depicts the distorted shadows cast by the four people as revealing what the artist thinks they are really like -- an apothecary casts the shadow of an enema, a censor casts the shadow of a devil, a hereditary peer casts the shadow of a pig, and a Jesuit casts the shadow of a turkey.

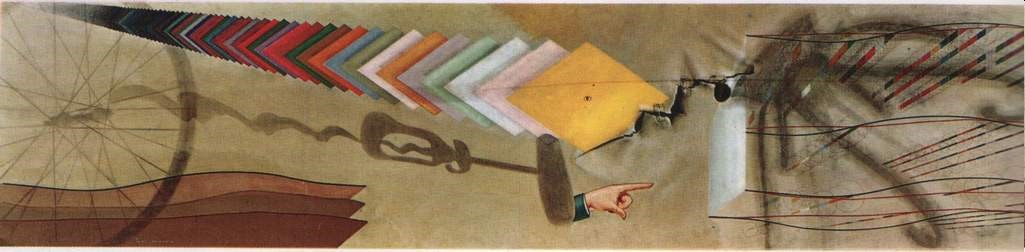

In some cases, the shadow itself can even dominate the painting. So, for example, while this photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson is nominally just of a boy sleeping, it is perhaps even more about the enormous shadow cast by an unseen temple on the wall behind him (Fig 19). Taking it even further, Marcel Duchamp’s painting Tu m’ (Fig 20) consists largely of cast shadows of “non-artistic” commonplace objects, such as a corkscrew or hat rack. Given that its title is probably short for “tu memmerdes’’ (you bore me) or “tu m’ennuies” (you annoy me), Duchamp seems to be saying that the whole idea of representational art is rather tedious [10]. This reaches an extreme with Malevich’s Black Square in which there is a total shadow with no light at all.

Mention here also needs to be made of a genre of paintings that depict the supposed “birth of painting”, in which the putative artist traces the outline of a person’s shadow on a wall. As we have already seen (Fig 3), Murillo illustrated this legendary event in 1660; this was followed by numerous works on the same theme, such as Alexander Runciman’s more romantic version, which depicts a woman drawing her lover’s picture on a wall as he lay asleep, by recording the profile of her lover’s slumbering head which had been cast upon a wall by the light of the moon (The Origin of Painting, 1771) [11]. In more recent times, the tradition formed the basis of Komar & Melamid’s parody, which highlights not only the absurdly inflated role of Great Leaders, but also the obsession with scantily-clad maidens that emerges so often in art.

# 3 Conveying mood

Shadows and light are two sides of the same coin. In contrast to light, which is often associated with purity, goodness and truth, shadows have traditionally had a bad press. For the Greeks, the shadow was a metaphor for the psyche, the soul [12]. A dead person’s soul was compared to a shadow, and Hades was the land of shadows, the land of death. In his Parable of the Cave, Plato likened ignorant people to beings who lived in a mental cave and who saw only the shadow of reality projected by the outside world onto the cave walls; not the real world itself outside the cave, which only knowledgeable people could see. And, of course, we are all aware of the very human fear of the dark, a distrust of what it may conceal, and awareness of its association with death.

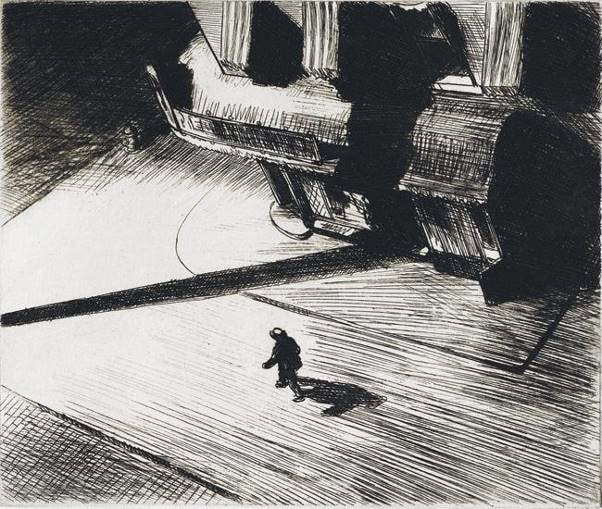

So perhaps it is understandable that shadows are commonly used by painters to impart a sense of drama, or menace, typically making the ordinary extraordinary, and even just making the dull look more interesting. For example, in Fig 22, a follower of Rembrandt has effectively used cast shadows to make a drama out of what might ordinarily be a conventional scene. Edward Hopper uses the elongated shadow of a streetlight, along with a bird’s eye viewpoint, to give a mysterious, perhaps threatening, atmosphere to a simple-seeming street scene in Night Shadows (Fig 23).

Shadows and light are two sides of the same coin. In contrast to light, which is often associated with purity, goodness and truth, shadows have traditionally had a bad press. For the Greeks, the shadow was a metaphor for the psyche, the soul [12]. A dead person’s soul was compared to a shadow, and Hades was the land of shadows, the land of death. In his Parable of the Cave, Plato likened ignorant people to beings who lived in a mental cave and who saw only the shadow of reality projected by the outside world onto the cave walls; not the real world itself outside the cave, which only knowledgeable people could see. And, of course, we are all aware of the very human fear of the dark, a distrust of what it may conceal, and awareness of its association with death.

So perhaps it is understandable that shadows are commonly used by painters to impart a sense of drama, or menace, typically making the ordinary extraordinary, and even just making the dull look more interesting. For example, in Fig 22, a follower of Rembrandt has effectively used cast shadows to make a drama out of what might ordinarily be a conventional scene. Edward Hopper uses the elongated shadow of a streetlight, along with a bird’s eye viewpoint, to give a mysterious, perhaps threatening, atmosphere to a simple-seeming street scene in Night Shadows (Fig 23).

Similarly, Caravaggio uses sharp directional shadows to disguise the presence of Jesus and highlight the dawning realisation of Matthew of his coming role (Fig 24). And the long shadows in Fig 25 tell us not only that a man is being chased but also suggest that the chaser is ominous and possibly dangerous.

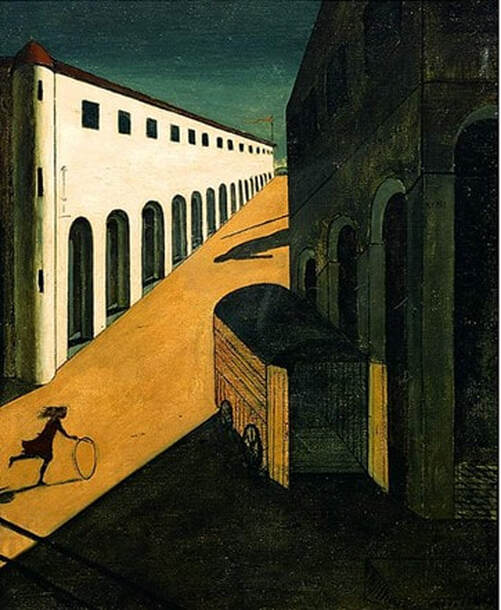

Shadows can also acquire special significance for some surrealist painters. In Fig 26, Giorgio de Chirico combines a number of these factors in one painting -- long shadows suggest late afternoon, a hidden statue is revealed only by its shadow, and a young girl with a hoop is seen only in silhouette. Combined with other, surreal aspects of the painting – the impossibly-flat surface of street, the truck on the right which is mysteriously lit from nowhere, and the shifting perspective of the buildings – they all contribute to the general air of dislocation and mystery.

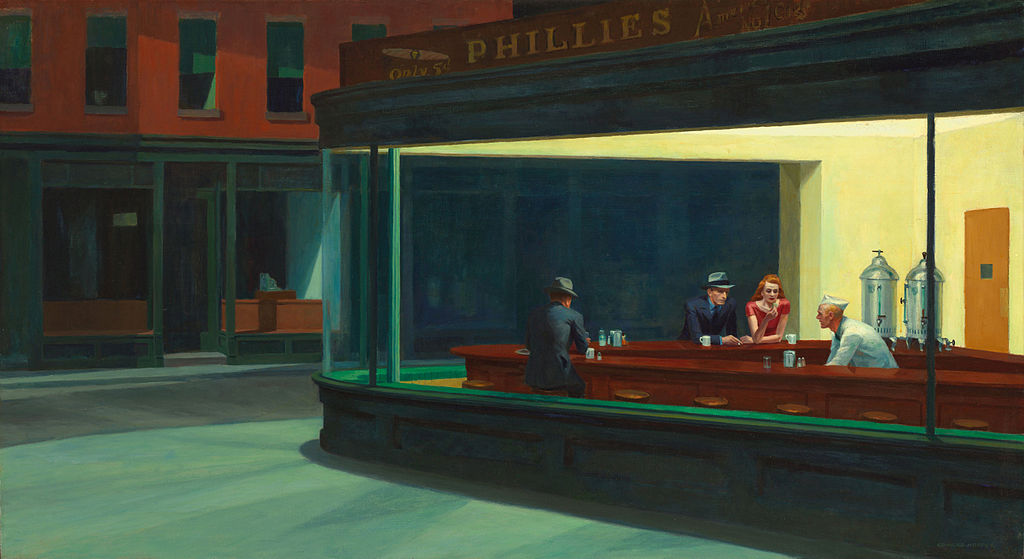

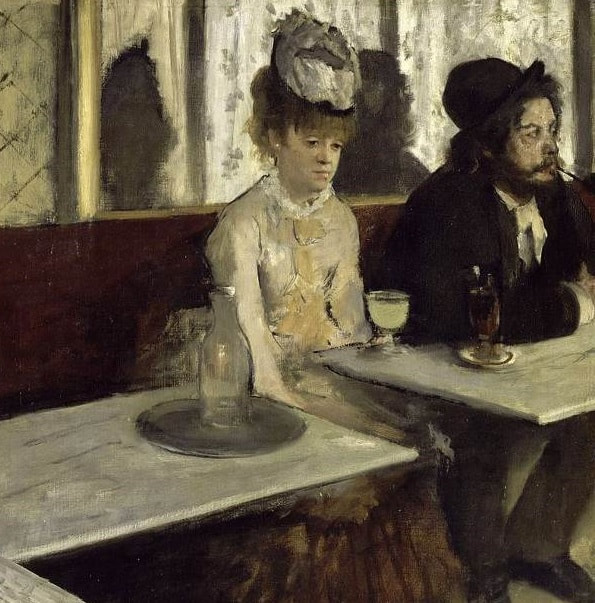

Shadows may also be used to create a sense of isolation or loneliness. Hopper uses shadows created by the harsh light in a diner to contribute to the sense of isolation in Nighthawks. In The Absinthe Drinkers, Degas uses the man and woman’s dark shadows on the wall behind them to suggest their shadowy, unhappy lives.

On the other hand, the use of soft, diffuse shadows can indicate safety, peace and warmth, as evident in many works by Impressionist painters and others. The Impressionists also reminded us that shadows do not need to be dark, with images of dappled sunlight and mauve shadows (or rather, shadows making the ground on which they fall look mauve).

#4 Shadows with special personalities

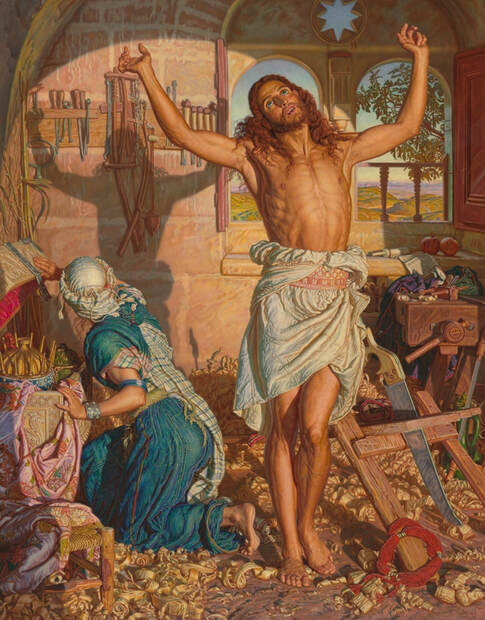

Some shadows can play a role in story-telling because they are shown as taking on a personality or power of their own. This is often associated with magic, mysticism, secrets or prophesy. We have already seen one example of this in Masaccio’s miraculous disease-curing shadow (Fig 7). In William Holman Hunt’s painting (Fig 31), the shadow on the wall of the house is not of the youthful Jesus depicted in the painting – it is a portent of his crucifixion which would occur some years later.

Some shadows can play a role in story-telling because they are shown as taking on a personality or power of their own. This is often associated with magic, mysticism, secrets or prophesy. We have already seen one example of this in Masaccio’s miraculous disease-curing shadow (Fig 7). In William Holman Hunt’s painting (Fig 31), the shadow on the wall of the house is not of the youthful Jesus depicted in the painting – it is a portent of his crucifixion which would occur some years later.

Sometimes, shadows actually take the place of a person or object that is important to the story. In Gerome’s Golgotha, what at first glance is a rather puzzling composition immediately becomes explicable when we realise that the shadows on the hillside on the right are of an unseen crucified Christ and the two thieves. Similarly, in Collins’ Rustic Civility, we have no idea why the boy is doffing his cap until we see the shadow cast by the unseen horseman.

In the converse situation, what does it mean when a person does not have a shadow, or misplaces or loses it? Some artists depict heavenly beings, evil spirits or other beings that are not flesh and blood, as not having shadows at all. Similarly, in literature, the shadow is often treated as symbolising a person’s soul, identity or human-ness. For example, in von Chamisso’s book The Wonderful Story of Peter Schlemihl, a man sells his shadow to the devil only to find that he is now shunned by society (Fig 34). In The Shadow, a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen (1847) when a man's shadow is detached, it takes on a life of its own and eventually usurps his identity. In the fantasy Peter and Wendy, by JM Barrie (1911), Peter Pan is the boy that never grows up, and the loss of his shadow seems to be a symbolic loss of his life. Fortunately, of course, Wendy is there to sew it back on, as memorably depicted in the Disney animated feature film.

#5 Artistic style and preferences

It is of course up to the artist to decide what role, if any, shadows should play in their art. This will be affected by various factors, including their own personal preferences and style of painting. We have hinted at this in our discussion of Matisse’s almost-floating dancers. Gauguin, for example, was another artist who hardly used shadows at all. Leonardo deprecated the unwise overuse of them, commenting that “light too conspicuously cut-off by shadows is exceedingly disapproved of …To avoid such awkwardness when you depict bodies in open country, do not make your figures appear determined by the sun, but contrive a certain amount of mist or of transparent cloud to be placed between the object and the sun” [13].

Some abstract painters, not interested in “reality”, would not feel any need to depict shadows. Artists preferring minimalist, or flat or graphic styles may deliberately opt not to include shadows. Eliminating shadows can also be important for some artists trying to create ethereal or symbolic effects in their paintings.

In summary then, shadows can be used to increase the realism of a painting, or used to distort reality, or simply ignored. Whichever it is, both their presence and their absence can provide important clues as to an artist’s approach to their art ■

© Philip McCouat, 2023. First published November 2023

We welcome your comments on this article

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “The Art of Shadows”, Journal of Art in Society, November 2023 www.artinsociety.com

Return to HOME

End Notes

[1] Research by Piaget cited in Victor I Stoichita, A Short History of the Shadow, Reaktion Books, London, 2019; and Interview with Stoichita in Cabinet Magazine: https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/24/turner_stoichita.php

[2] Nijad A Al-Najdawi et al, “A-survey-of-cast-shadow-detection-algorithms” in Semantic Scholar https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-survey-of-cast-shadow-detection-algorithms-Al-Najdawi-Bez/8ae34fc4867de92744b7e119186ad681694aef2a/figure/2]

[3] Philip McCouat, “Art and Survival in Patagonia”, in Journal of Art in Society, https://www.artinsociety.com/art-and-survival-in-patagonia.html

[4] See generally Robert Rosenblum, “The Origin of Painting: A Problem in the Iconography of Romantic Classicism”, The Art Bulletin, vol 39 No 4 (Dec 1957, 279-290)

[5] The Holy Bible, Acts of the Apostles 3

[6] Floriane Heine, “In the Land of Shadows”, in The First Time, Bucher, Munich 2007, pp 40-47, at 43

[7] See also Riccardo Falcinelli, Chromorama: How Colour Changed Our Way of Seeing, Penguin Books, (transl) 2022. at 384

[8] E H Gombrich, Shadows: The Depiction of Cast Shadows in Western Art, National Gallery Publications, London, 1995 at 52

[9] Joan K Stemmler, “The Physiological Portraits of Johann Caspar Lavater”, The Art Bulletin, Vol 75, No 1 (Mar 1993), 151]. See also Lauren Muney, “Silhouettes in History”, 2014 at https://www.silhouettesbyhand.com/history

[10] Yale University Art Gallery note on the painting https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/50128

[11] Rosenblum, op cit

[12] Stoichita, op cit

[13] Trattato della Pittura, cited in Gombrich, op cit at 20.

© Philip McCouat, 2023. First published November 2023

Return to HOME

It is of course up to the artist to decide what role, if any, shadows should play in their art. This will be affected by various factors, including their own personal preferences and style of painting. We have hinted at this in our discussion of Matisse’s almost-floating dancers. Gauguin, for example, was another artist who hardly used shadows at all. Leonardo deprecated the unwise overuse of them, commenting that “light too conspicuously cut-off by shadows is exceedingly disapproved of …To avoid such awkwardness when you depict bodies in open country, do not make your figures appear determined by the sun, but contrive a certain amount of mist or of transparent cloud to be placed between the object and the sun” [13].

Some abstract painters, not interested in “reality”, would not feel any need to depict shadows. Artists preferring minimalist, or flat or graphic styles may deliberately opt not to include shadows. Eliminating shadows can also be important for some artists trying to create ethereal or symbolic effects in their paintings.

In summary then, shadows can be used to increase the realism of a painting, or used to distort reality, or simply ignored. Whichever it is, both their presence and their absence can provide important clues as to an artist’s approach to their art ■

© Philip McCouat, 2023. First published November 2023

We welcome your comments on this article

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “The Art of Shadows”, Journal of Art in Society, November 2023 www.artinsociety.com

Return to HOME

End Notes

[1] Research by Piaget cited in Victor I Stoichita, A Short History of the Shadow, Reaktion Books, London, 2019; and Interview with Stoichita in Cabinet Magazine: https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/24/turner_stoichita.php

[2] Nijad A Al-Najdawi et al, “A-survey-of-cast-shadow-detection-algorithms” in Semantic Scholar https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-survey-of-cast-shadow-detection-algorithms-Al-Najdawi-Bez/8ae34fc4867de92744b7e119186ad681694aef2a/figure/2]

[3] Philip McCouat, “Art and Survival in Patagonia”, in Journal of Art in Society, https://www.artinsociety.com/art-and-survival-in-patagonia.html

[4] See generally Robert Rosenblum, “The Origin of Painting: A Problem in the Iconography of Romantic Classicism”, The Art Bulletin, vol 39 No 4 (Dec 1957, 279-290)

[5] The Holy Bible, Acts of the Apostles 3

[6] Floriane Heine, “In the Land of Shadows”, in The First Time, Bucher, Munich 2007, pp 40-47, at 43

[7] See also Riccardo Falcinelli, Chromorama: How Colour Changed Our Way of Seeing, Penguin Books, (transl) 2022. at 384

[8] E H Gombrich, Shadows: The Depiction of Cast Shadows in Western Art, National Gallery Publications, London, 1995 at 52

[9] Joan K Stemmler, “The Physiological Portraits of Johann Caspar Lavater”, The Art Bulletin, Vol 75, No 1 (Mar 1993), 151]. See also Lauren Muney, “Silhouettes in History”, 2014 at https://www.silhouettesbyhand.com/history

[10] Yale University Art Gallery note on the painting https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/50128

[11] Rosenblum, op cit

[12] Stoichita, op cit

[13] Trattato della Pittura, cited in Gombrich, op cit at 20.

© Philip McCouat, 2023. First published November 2023

Return to HOME