Art in a Speeded up World - Part 1

By Philip McCouat

|

Art in a Speeded Up World: Overview

Part 1: Changing concepts of time Part 2: The 'new' time in literature Part 3:The 'new' time in painting |

Other articles on photography:

Early influences of photography on art Why wasn’t photography invented earlier? ------------------------------------------------------- |

Part 1: Changing concepts of time

Traditionally, in Christian societies, it had commonly been believed that time belonged only to God, its creator. This meant that time could not be treated as a commodity. To grasp it, measure it, or turn it to account was a sin; hence the early prohibition on usury [1]. Time was the great leveller, able to reveal truth, and with the power to destroy beauty, human vanities, worldly fame and ultimately earthly life itself.

The passage of time was regarded as continuous [2]. Changes in time were marked primarily by the regular cycle of religious events, seasons and feast days. Even after the invention of the mechanical clock in the fourteenth century, most people were far less concerned with the passage of time in their daily life than we are today. Even years varied from place to place and were considered quite personal or local [3].

In Western art, in accordance with these traditional concepts, time was commonly personified as a judgmental Father Time, an ancient man, often winged to reflect how ‘time flies’, armed with a scythe and sometimes accompanied by an hourglass [4]. Time was typically portrayed as passing steadily and inevitably. Popular subjects included the three ages of man, the passing of the seasons, the end of fleeting worldly pleasures and earthly existence [5]. The focus was firmly on the inevitable transience of life, compared to the eternal and timeless glory of God’s kingdom [6].

Photography and perceptual time

One of a number of factors that contributed to changing these views about time was the 1830s introduction of photography [7].

Photography’s most important time-related feature [8] was its capacity to capture and process images faster than the human eye [9]. This had a number of important, but sometimes paradoxical effects. Firstly, it provided unprecedentedly accurate information as to how things physically moved. In 1878, Muybridge’s sensational exhibition of short-exposure photography disclosed the movement of animals and humans in step-by-step detail. Equally startling chronophotographic studies (‘pictures of time’) were later produced by Marey, showing successive phases of continuous movement in a single picture (Fig 1).

Traditionally, in Christian societies, it had commonly been believed that time belonged only to God, its creator. This meant that time could not be treated as a commodity. To grasp it, measure it, or turn it to account was a sin; hence the early prohibition on usury [1]. Time was the great leveller, able to reveal truth, and with the power to destroy beauty, human vanities, worldly fame and ultimately earthly life itself.

The passage of time was regarded as continuous [2]. Changes in time were marked primarily by the regular cycle of religious events, seasons and feast days. Even after the invention of the mechanical clock in the fourteenth century, most people were far less concerned with the passage of time in their daily life than we are today. Even years varied from place to place and were considered quite personal or local [3].

In Western art, in accordance with these traditional concepts, time was commonly personified as a judgmental Father Time, an ancient man, often winged to reflect how ‘time flies’, armed with a scythe and sometimes accompanied by an hourglass [4]. Time was typically portrayed as passing steadily and inevitably. Popular subjects included the three ages of man, the passing of the seasons, the end of fleeting worldly pleasures and earthly existence [5]. The focus was firmly on the inevitable transience of life, compared to the eternal and timeless glory of God’s kingdom [6].

Photography and perceptual time

One of a number of factors that contributed to changing these views about time was the 1830s introduction of photography [7].

Photography’s most important time-related feature [8] was its capacity to capture and process images faster than the human eye [9]. This had a number of important, but sometimes paradoxical effects. Firstly, it provided unprecedentedly accurate information as to how things physically moved. In 1878, Muybridge’s sensational exhibition of short-exposure photography disclosed the movement of animals and humans in step-by-step detail. Equally startling chronophotographic studies (‘pictures of time’) were later produced by Marey, showing successive phases of continuous movement in a single picture (Fig 1).

Short-exposure photography of this type expanded the reach of human eyesight in the temporal domain. To the amazement of viewers, a trotting horse was revealed as having all four legs off the ground for an instant. The prosaic action of a raindrop falling into a puddle became transformed into an extraordinary vision. These revelations provided a striking demonstration of how time – previously regarded as a flow – could be visually deconstructed and fragmented, and of how aspects of movements could be isolated and considered on their own terms.

The speed of photography also revealed a world that often included fragmentary views based on discontinuous forms and unexpected juxtapositions that occur in nature, but which are edited out in adult human perception.This sometimes meant that photographs had a cropped appearance, either accidentally (as where a snapshot captured a part of a figure entering the scene from the side), or deliberately (as where a photo was edited to highlight the action, draw the viewer into the scene, or even just to save space). These features contributed to the impression that the photograph had the effect of somehow stopping time.

As a result, photographic images acquired a quality that we rarely experience when looking at painted forms – immediacy [10]. This contrasted sharply with the Renaissance tradition in which paintings were typically contained and finite, carefully composed, complete within themselves, and clearly defined by a non-intrusive framing edge [11]. The new framing edges, coupled with shorter exposure times, reinforced impressions of the ‘fleeting moment’ of arrested motion, a spirit of temporality, momentariness or movement continuing beyond the frame into real space. Even for relatively static subjects, photography revealed that reality had a transitory and ever-changing nature. As Szarkowski pointed out, ‘each subtle variation in viewpoint or light, each passing moment, each change in the tonality of the print, caused a new picture…. the wall of a building in the sun was never twice the same’[12].

Additional time-defying effects were also produced by special photographic techniques. Innovations such as spirit photography, combination printing and retouching demonstrated that the version of reality that photography revealed could be manipulated. Spirit photographs cynically exploited the recently-discovered effect of double exposure to produce realistic-looking yet temporally impossible portraits of living people, with beloved dead relatives usually hovering behind them [13]. This contributed enormously to the rise of belief in spiritualism and ‘the other side’ which had first surfaced in Germany back in the 1840s [14]. The belief that communication with the departed might be possible was in many ways quite understandable in the late nineteenth century, given the recent developments of other ‘invisible’ and seemingly impossible modes of communication, such as the telephone and the telegraph [15].

The subsequent unmasking of spirit photographs as fakes shocked those who had implicitly believed the evidence of their own eyes. In a similar way, the first retouched photograph, in 1855, with its undeniable confirmation that the camera could lie, astounded crowds who had regarded photography as the embodiment of authenticity [16]. Because photographic images seemed so real, evidence of their manipulation was even more shocking and potentially influential.

This of course was not the only paradox that photography presented. For artists and non-artists alike, photography also served to highlight a number of temporal contradictions.Thus, photography was a technological breakthrough in a society obsessed with the future, yet it enabled society to hold onto the past. A photograph could freeze time to an abrupt halt yet, in another equally valid sense, express the impression of transition. Conversely, photography could portray a fleeting moment, yet seemingly do so forever. Photographs could bring the past into the present or, conversely, could take the present back into the past. And, as we have just seen, photographs were capable of providing an objective, accurate view of the world, yet, for that very reason, could also be vehicles of deception and manipulation.

Many of these effects were even further highlighted with the invention of the cinematograph, or ‘animated photography’ [17]. Moving films presented the phenomenon of a 'mechanical eye' in constant movement, 'freed from the boundaries of time and space' [17A]. They left first-time viewers sitting with ‘mouths open, thunderstruck, speechless with amazement’[18], and achieved such unbelievable immediacy that first-time audiences jumped aside in terror to avoid being hit by a train as it appeared to steam toward them [19]. Film also had unprecedented capacity to manipulate time and movement by artificially slowing it down, speeding it up, stopping it, making it go backwards, inserting or truncating time gaps or jumps, and performing seemingly impossible feats of time trickery with flash backs or flash forwards. In these ways, ‘cinematic time’ became independent of ‘real time’. Film also embodied its own fundamental paradox – that it created ‘movement’ by frames showing ‘stopped time’[20].

Technological and social time

There were of course other major factors that were operating to change people’s conceptions of time and space.

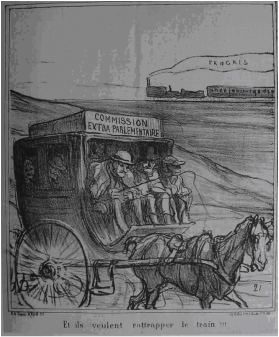

From the 1830s onwards, the railways had spread rapidly, as locomotives ‘burst rather than stole or crept upon the world’[21]. This had a transforming effect on many aspects of people’s lives. Before the railway, the fastest mode of travel had been a horse. People in 1800 travelled at much the same speed as they had in the days of Julius Caesar, two thousand years before. Suddenly, almost overnight it seemed, people could travel long distances six times faster [22]. The locomotive gave ‘a new celerity’ to time [23], with an impact that was ‘in the highest degree dramatic’[24]. The description ‘slow coach’ entered the language almost immediately [25]. W R Greg complained in 1875 that 'the most salient characteristic of life in this latter portion of the 19th century is its SPEED' [25A]. Daumier’s satire on governmental bureaucratic delays contrasts the old fashioned coach with a train representing progress with the mocking comment – ‘and they think they might be able to overtake the train!’ (Fig 2).

The speed of photography also revealed a world that often included fragmentary views based on discontinuous forms and unexpected juxtapositions that occur in nature, but which are edited out in adult human perception.This sometimes meant that photographs had a cropped appearance, either accidentally (as where a snapshot captured a part of a figure entering the scene from the side), or deliberately (as where a photo was edited to highlight the action, draw the viewer into the scene, or even just to save space). These features contributed to the impression that the photograph had the effect of somehow stopping time.

As a result, photographic images acquired a quality that we rarely experience when looking at painted forms – immediacy [10]. This contrasted sharply with the Renaissance tradition in which paintings were typically contained and finite, carefully composed, complete within themselves, and clearly defined by a non-intrusive framing edge [11]. The new framing edges, coupled with shorter exposure times, reinforced impressions of the ‘fleeting moment’ of arrested motion, a spirit of temporality, momentariness or movement continuing beyond the frame into real space. Even for relatively static subjects, photography revealed that reality had a transitory and ever-changing nature. As Szarkowski pointed out, ‘each subtle variation in viewpoint or light, each passing moment, each change in the tonality of the print, caused a new picture…. the wall of a building in the sun was never twice the same’[12].

Additional time-defying effects were also produced by special photographic techniques. Innovations such as spirit photography, combination printing and retouching demonstrated that the version of reality that photography revealed could be manipulated. Spirit photographs cynically exploited the recently-discovered effect of double exposure to produce realistic-looking yet temporally impossible portraits of living people, with beloved dead relatives usually hovering behind them [13]. This contributed enormously to the rise of belief in spiritualism and ‘the other side’ which had first surfaced in Germany back in the 1840s [14]. The belief that communication with the departed might be possible was in many ways quite understandable in the late nineteenth century, given the recent developments of other ‘invisible’ and seemingly impossible modes of communication, such as the telephone and the telegraph [15].

The subsequent unmasking of spirit photographs as fakes shocked those who had implicitly believed the evidence of their own eyes. In a similar way, the first retouched photograph, in 1855, with its undeniable confirmation that the camera could lie, astounded crowds who had regarded photography as the embodiment of authenticity [16]. Because photographic images seemed so real, evidence of their manipulation was even more shocking and potentially influential.

This of course was not the only paradox that photography presented. For artists and non-artists alike, photography also served to highlight a number of temporal contradictions.Thus, photography was a technological breakthrough in a society obsessed with the future, yet it enabled society to hold onto the past. A photograph could freeze time to an abrupt halt yet, in another equally valid sense, express the impression of transition. Conversely, photography could portray a fleeting moment, yet seemingly do so forever. Photographs could bring the past into the present or, conversely, could take the present back into the past. And, as we have just seen, photographs were capable of providing an objective, accurate view of the world, yet, for that very reason, could also be vehicles of deception and manipulation.

Many of these effects were even further highlighted with the invention of the cinematograph, or ‘animated photography’ [17]. Moving films presented the phenomenon of a 'mechanical eye' in constant movement, 'freed from the boundaries of time and space' [17A]. They left first-time viewers sitting with ‘mouths open, thunderstruck, speechless with amazement’[18], and achieved such unbelievable immediacy that first-time audiences jumped aside in terror to avoid being hit by a train as it appeared to steam toward them [19]. Film also had unprecedented capacity to manipulate time and movement by artificially slowing it down, speeding it up, stopping it, making it go backwards, inserting or truncating time gaps or jumps, and performing seemingly impossible feats of time trickery with flash backs or flash forwards. In these ways, ‘cinematic time’ became independent of ‘real time’. Film also embodied its own fundamental paradox – that it created ‘movement’ by frames showing ‘stopped time’[20].

Technological and social time

There were of course other major factors that were operating to change people’s conceptions of time and space.

From the 1830s onwards, the railways had spread rapidly, as locomotives ‘burst rather than stole or crept upon the world’[21]. This had a transforming effect on many aspects of people’s lives. Before the railway, the fastest mode of travel had been a horse. People in 1800 travelled at much the same speed as they had in the days of Julius Caesar, two thousand years before. Suddenly, almost overnight it seemed, people could travel long distances six times faster [22]. The locomotive gave ‘a new celerity’ to time [23], with an impact that was ‘in the highest degree dramatic’[24]. The description ‘slow coach’ entered the language almost immediately [25]. W R Greg complained in 1875 that 'the most salient characteristic of life in this latter portion of the 19th century is its SPEED' [25A]. Daumier’s satire on governmental bureaucratic delays contrasts the old fashioned coach with a train representing progress with the mocking comment – ‘and they think they might be able to overtake the train!’ (Fig 2).

_ The effect was described, with some hyperbole, as an ‘annihilation of space and time’[26] – if distance was measured in time, then the world had suddenly begun to shrink [27]. Visually, instead of the slow, steady unfolding of the landscape, train passengers experienced a succession of ‘rapidly superseded fragments, snatched glimpses and staccato juxtapositions’, an unfolding of the landscape in flickering surfaces as one was carried swiftly past it [28]. The German poet Heinrich Heine commented, ‘What changes are happening now, are being imposed on our perceptions and imaginations! Even the elementary concepts of time and space are swaying’. William Makepeace Thackeray commented wonderingly, 'We who have lived before railways were made, belong to another world.... [I]t was only yesterday; but what a gulf between now and then!' [28A]. So marked was the change that English artist John Cooke Bourne was prompted to specifically create artworks ‘to display the stations, bridges, tunnels and viaducts to the passengers who were whirled past them so rapidly that, otherwise, they had no chance to appreciate their worth’[29]. This speeded-up visual sensation was not limited to passengers on board the train. Even for spectators, ‘an engine as it draws near, appears to be rapidly magnified and as it would fill up the entire space between the banks and absorb everything in its vortex’[30].

In one sense, of course, the concept of ‘annihilating time’ was quite misleading. In fact, time was starting to assume a much greater role in people’s lives. So, for example, the seemingly reckless new speeds demanded timetables and precise timekeeping in order to avoid the horrific crashes that marked the early years of train travel [31]. As rail travel was fast enough to make differences in local time significant, this in turn led to moves towards the standardisation of time into time zones, a step ultimately made possible by the development of the electric telegraph [32]. Just as with photography, time – previously considered natural, universal and concrete – thus became a more abstract concept that could be manipulated by humans.

Timetables also had significant effects on people’s personal habits. ‘Catching’ a train ‘energised punctuality, discipline, and attention’ [33]. As Henry Thoreau commented, ‘Have not men improved somewhat in punctuality since the railroad was invented? Do they not talk and think somewhat faster in the [rail] depot than they did in the stage [coach] office?’[34]. One 1862 railway guide devoted four pages to the importance of being on time, sternly warning intending passengers that 'the time of departure stated in the [time]table is no fiction; the strictest regularity is observed, and indeed must necessarily be, to prevent the terrible consequences that might otherwise ensue'[34A]. Reflecting the new mood, pocket watches changed to mass production in the 1850s [35], and second hands for clocks stated to become commonplace [36]. From 1855 onwards, all clocks at the main London post offices began to be corrected daily by electric telegraph signals from the Royal Observatory at Greenwich [37]. The introduction of observatory-precise standard time actually made it a marketable commodity – in both England and America, town jewellers bought access to it from observatories for large annual fees and advertised it in clocks in their shop windows, gaining prestige and custom [38]. The installation in 1858 of the giant clock face of Big Ben, accurate to one second, towering over Britain’s centre of power at the Houses of Parliament in London, was an extraordinarily potent reminder of the central position that time was beginning to occupy in everyday life [39].

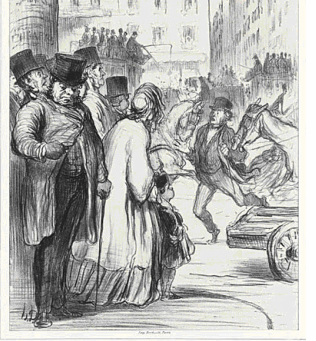

This sense extended even to holidays. Daumier’s satiric Trains of Pleasure (1864), commenting on the booming tourism that the railways spawned, depicts a mad scramble to get on a train, with the artist’s wry caption, ‘Having found a seat after ten desperate attempts to board the train, a first tender feeling of holiday relaxation emerges’ (Fig 3).

In one sense, of course, the concept of ‘annihilating time’ was quite misleading. In fact, time was starting to assume a much greater role in people’s lives. So, for example, the seemingly reckless new speeds demanded timetables and precise timekeeping in order to avoid the horrific crashes that marked the early years of train travel [31]. As rail travel was fast enough to make differences in local time significant, this in turn led to moves towards the standardisation of time into time zones, a step ultimately made possible by the development of the electric telegraph [32]. Just as with photography, time – previously considered natural, universal and concrete – thus became a more abstract concept that could be manipulated by humans.

Timetables also had significant effects on people’s personal habits. ‘Catching’ a train ‘energised punctuality, discipline, and attention’ [33]. As Henry Thoreau commented, ‘Have not men improved somewhat in punctuality since the railroad was invented? Do they not talk and think somewhat faster in the [rail] depot than they did in the stage [coach] office?’[34]. One 1862 railway guide devoted four pages to the importance of being on time, sternly warning intending passengers that 'the time of departure stated in the [time]table is no fiction; the strictest regularity is observed, and indeed must necessarily be, to prevent the terrible consequences that might otherwise ensue'[34A]. Reflecting the new mood, pocket watches changed to mass production in the 1850s [35], and second hands for clocks stated to become commonplace [36]. From 1855 onwards, all clocks at the main London post offices began to be corrected daily by electric telegraph signals from the Royal Observatory at Greenwich [37]. The introduction of observatory-precise standard time actually made it a marketable commodity – in both England and America, town jewellers bought access to it from observatories for large annual fees and advertised it in clocks in their shop windows, gaining prestige and custom [38]. The installation in 1858 of the giant clock face of Big Ben, accurate to one second, towering over Britain’s centre of power at the Houses of Parliament in London, was an extraordinarily potent reminder of the central position that time was beginning to occupy in everyday life [39].

This sense extended even to holidays. Daumier’s satiric Trains of Pleasure (1864), commenting on the booming tourism that the railways spawned, depicts a mad scramble to get on a train, with the artist’s wry caption, ‘Having found a seat after ten desperate attempts to board the train, a first tender feeling of holiday relaxation emerges’ (Fig 3).

_

As the Times complained in 1861, railway time turned holidays into work – and tiring work at that. It demanded ‘perpetual attention to time, and all the anxieties and irritations of that responsibility’. National life was now ruled by ‘railway time’, and Thomas Cook’s highly-organised travel groups subjected the nation’s leisure to factory discipline [40]. Charles Dickens commented that this replacement of local time by standardised railway time made it seem ‘as if the sun itself had given in’[41].

It also seemed to some that the need for punctuality in turn contributed to increased anxiety. As the physician G M Beard commented in 1881:

“The perfection of clocks and the invention of watches have something to do with modern nervousness, since they compel us to be on time, and excite the habit of looking to see the exact moment, so as not to be late for trains or appointments. Before the general use of these instruments of precision in time, there was a wider margin for all appointments; a longer period was required and prepared for, especially in travelling – coaches of the olden period were not expected to start like steamers or trains, on the instant – men judged of the time by probabilities, by looking at the sun, and needed not, as a rule, to be nervous about the loss of a moment, and had incomparably fewer experiences wherein a delay of a few moments might destroy the hopes of a lifetime” [42]

It was even speculated that the anxiety to be ‘on time’, the hurrying pace, and the running to catch trains may have contributed to the increase in deaths from heart failure between 1851 and 1870 [43].

Industrialisation and urbanisation

Further pressures on time resulted from the rapid industrialisation and urbanisation of the 19th century. At the beginning of the century, 80% of people in England and Wales lived in the countryside, but by 1851 more than 50% of the population lived in cities [44] – the first time this had happened anywhere in the world. Highly-mechanised and organised industry demanded standardisation, timetabling and precision in all aspects, from the time people started work to the time they had their lunch. Time became a business commodity. In conjunction with the virtually instant communication that was enabled by the recently-invented electric telegraph and, later, the telephone, this provided another example of the so-called ‘annihilation of space and time’, reducing the time spent in motion from one place to another. For businesses, getting quick access to vital information – stock market changes, commodity price movements and so on – became a virtual necessity [45].

Karl Marx suggested that ‘the clock is the first automatic machine applied to practical purposes; the whole theory of production of regular motion was developed through it’[46]. Urban business life increasingly began to depend entirely on the punctual integration of all activities and mutual relations into a stable and impersonal time schedule. Thus, Bundy clocks for recording sign-on and sign-off times for workers were invented in 1885-88, stop watches were introduced in 1869, and time-and-motion studies were devised and pioneered by Frederick (‘Speedy’) Taylor in the 1870s. The assembly-line method of manufacture was introduced, with the process being fragmented into modular tasks and modular time allowances. At the same time, the predictable and familiar rural way of life became replaced by the fleeting experiences of the city – short, intense, accidental and arbitrary [47]. These developments thus revolutionised the way that people lived and worked.

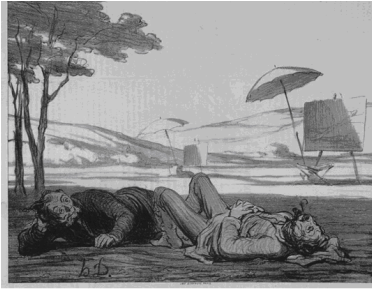

The contrast between these new urban concepts and traditional concepts of time was illustrated in two lithographs by Daumier in 1862 – The New Paris, characterised by an urban rush, crowds and the checking of a watch (Fig 4) and Landscapists at Work, representing ‘natural’, rural pre-industrial time, characterised by freedom and pleasure, with its suggestion that may artists were, at this stage, still enjoying living in the past (Fig 5) [48].

It also seemed to some that the need for punctuality in turn contributed to increased anxiety. As the physician G M Beard commented in 1881:

“The perfection of clocks and the invention of watches have something to do with modern nervousness, since they compel us to be on time, and excite the habit of looking to see the exact moment, so as not to be late for trains or appointments. Before the general use of these instruments of precision in time, there was a wider margin for all appointments; a longer period was required and prepared for, especially in travelling – coaches of the olden period were not expected to start like steamers or trains, on the instant – men judged of the time by probabilities, by looking at the sun, and needed not, as a rule, to be nervous about the loss of a moment, and had incomparably fewer experiences wherein a delay of a few moments might destroy the hopes of a lifetime” [42]

It was even speculated that the anxiety to be ‘on time’, the hurrying pace, and the running to catch trains may have contributed to the increase in deaths from heart failure between 1851 and 1870 [43].

Industrialisation and urbanisation

Further pressures on time resulted from the rapid industrialisation and urbanisation of the 19th century. At the beginning of the century, 80% of people in England and Wales lived in the countryside, but by 1851 more than 50% of the population lived in cities [44] – the first time this had happened anywhere in the world. Highly-mechanised and organised industry demanded standardisation, timetabling and precision in all aspects, from the time people started work to the time they had their lunch. Time became a business commodity. In conjunction with the virtually instant communication that was enabled by the recently-invented electric telegraph and, later, the telephone, this provided another example of the so-called ‘annihilation of space and time’, reducing the time spent in motion from one place to another. For businesses, getting quick access to vital information – stock market changes, commodity price movements and so on – became a virtual necessity [45].

Karl Marx suggested that ‘the clock is the first automatic machine applied to practical purposes; the whole theory of production of regular motion was developed through it’[46]. Urban business life increasingly began to depend entirely on the punctual integration of all activities and mutual relations into a stable and impersonal time schedule. Thus, Bundy clocks for recording sign-on and sign-off times for workers were invented in 1885-88, stop watches were introduced in 1869, and time-and-motion studies were devised and pioneered by Frederick (‘Speedy’) Taylor in the 1870s. The assembly-line method of manufacture was introduced, with the process being fragmented into modular tasks and modular time allowances. At the same time, the predictable and familiar rural way of life became replaced by the fleeting experiences of the city – short, intense, accidental and arbitrary [47]. These developments thus revolutionised the way that people lived and worked.

The contrast between these new urban concepts and traditional concepts of time was illustrated in two lithographs by Daumier in 1862 – The New Paris, characterised by an urban rush, crowds and the checking of a watch (Fig 4) and Landscapists at Work, representing ‘natural’, rural pre-industrial time, characterised by freedom and pleasure, with its suggestion that may artists were, at this stage, still enjoying living in the past (Fig 5) [48].

_

From the 1840s, there was an explosive growth in the popular penny press and the accompanying phenomenon of ‘news’, or ‘stories of the day’ which provided ‘new, thrilling and sensational’ fodder for their readers [49]. Thanks to the new rail services, the electric telegraph and the speed of steam printing presses, a newspaper printed in London could be in Manchester in time for morning delivery [50]. The result was that any local incident, if important or sensational enough, could almost instantaneously become a subject of national interest. For readers, suddenly it seemed that so much more was happening so much more quickly, an impression heightened by the introduction of ‘railway post offices’, which dramatically cut postal delivery times by transporting and sorting letters en-route [51]. By 1883, as a result of the laying of the submarine telegraph cables, instantaneity also extended to international events, enabling news of the explosion of the volcano at Krakatoa to be transmitted around the world in minutes. The effect, according to one modern commentator, was that ‘the world’s people suddenly became part of a new brotherhood [sic] of knowledge’; in one sense, the event could be seen as the birth of the modern phenomenon known as the ‘Global Village’’[52].

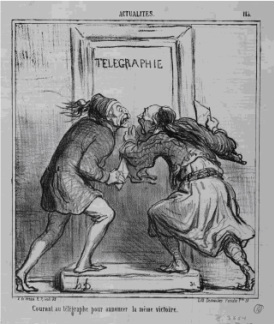

The new premium placed on timing also played a crucial role in determining how the perception of news could be shaped. In some cases, what increasingly came to matter was not so much the truth, but who was first in disseminating their version of the ‘story’. The phenomenon was parodied in Daumier’s 1867 lithograph Running to the Telegraph Office to Announce the Same Victory (Fig 6), which shows Greek and Turk jostling each other to get to the telegraph office in their desperate bid to be first to transmit their own biased version of the war news.

The new premium placed on timing also played a crucial role in determining how the perception of news could be shaped. In some cases, what increasingly came to matter was not so much the truth, but who was first in disseminating their version of the ‘story’. The phenomenon was parodied in Daumier’s 1867 lithograph Running to the Telegraph Office to Announce the Same Victory (Fig 6), which shows Greek and Turk jostling each other to get to the telegraph office in their desperate bid to be first to transmit their own biased version of the war news.

_ The capacity of the electric telegraph to obtain virtually instant news from distant places had other, more unexpected effects on people’s lives. So, for example, in London, the new availability of regularly-updateable information about approaching weather patterns from all parts of the country led to the development of ‘weather forecasts’ and the creation of a government Meteorological Office in 1854, with daily weather reports starting to be published in the London Times from 1860 [53].

Sport and leisure

We have already noted the impact that the availability and speed of railways had in increasing and regimenting tourism. The increased importance of time also started being reflected in people’s other leisure activities. In England, for example, increased leisure times had been made possible by the half Saturday holiday derived from industrialisation. Together with revived interest in team sports in the English public schools, increased networks of schools that had inter school sporting competitions, and a revival of the idea of the ancient Olympic Games [54], this led to an extraordinary mid-century revival of interest in organised sport and games. This interest was also facilitated the faster transport that enabled people to attend bigger, more organised sporting events, and by higher wages which enabled them to pay to be spectators at them. Activities that formerly were the preserve of professionals and gamblers (such as ‘pedestrianism’) increasingly became popular among the wider population of amateurs. Increasingly, accurate timing started to be a prime consideration in these activities. By the 1850s, the advent of precisely-measured athletic tracks enabled accurate times for each event to be recorded. By 1869, this had been further refined by the development of the stop watch [55]. Together with improved international communications, the novel concept of ‘world records’ began to claim a hold on the public imagination.

Intellectual changes affecting time

During the nineteenth century, firmly-held beliefs about the age of the world – and the beginning of time – came under sustained attack on a number of fronts.

From about 1650, the vast mass of Christians had believed implicitly that time began about 6,000 years ago, when God created heaven and earth. This actually had Biblical sanction; side annotations to Genesis in the King James Version published from 1701 referred to Bishop Ussher’s calculation of the beginning of time as occurring on the night preceding 23 October 4004 BC [56]. Geologists and other ‘scientists’ (as they became known after the word was coined in 1834), seriously challenged this traditional concept as they pushed back their estimates of the age of the earth, in books that sometimes outsold popular novels [57].

The discoveries of the new discipline of astronomy, aided by significant improvements in telescopes [57A], further disrupted conventional notions of time and space. Photographs taken of celestial bodies [58] enabled public appreciation of other worlds, unimaginable distances and ages away. Estimates of the age of the universe grew exponentially to almost unimaginable levels. The need to express these incredible distances led to the development of the mind-stretching concept of the ‘light year’ in the 1880s. By 1905, the estimated age of the world was up to 1.64 billion years. As the geologist G. P. Scrope commented, ‘the leading idea which is present in all our researches, and which accompanies every fresh observation, the sound which to the ear of the student of Nature seems continually echoed from every part of her works, is – Time! Time! Time!’[59].

For many, all this was deeply unsettling. As Gould comments, ‘[W]hat could be more comforting, what more convenient for human domination, that the traditional concept of a young earth, ruled by human will within days of its origin. What more threatening, by contrast, [was] the notion of an almost incomprehensible immensity, with human habitation restricted to a millimicrosecond at the very end! [60]

Even more challenging implications of this immense time-scale became shockingly evident with the publication of Darwin’s On The Origin of Species in 1859. A vast age for the earth provided a feasible time frame for the operation of the Darwinian theory of evolution, presenting a challenge to the public’s conception of themselves as humans, as well as to their Christian faith [61]. Previously-held concepts of the immutability of species over time also suffered major challenges with the increasing discoveries of fossils of long-extinct life forms, which scientists used to establish a chronology of rock strata which suggested an immense history of progressive change. The significance of mutability was enormous. It meant that the future seemed much less predictable, as it could no longer be assumed that things would stay as they were in the present. Darwin himself said that stating his belief that species were not immutable was ‘like confessing to a murder’[62].

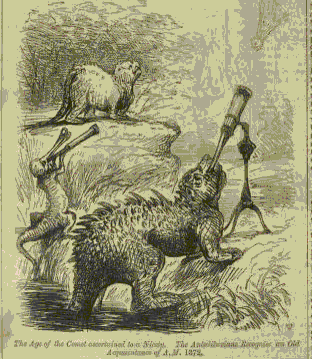

Some appreciation of the time-confusion that many would have felt was reflected in a Punch cartoon (Fig 7), inspired by the re-appearance in 1861 of the ‘Great Comet’[63]. The cartoon, The Age of the Comet Ascertained to a Nicety, shows ‘antediluvian’ dinosaurs peering through telescopes as they ‘recognise an old acquaintance of 1372’, based on the fanciful idea that the reptiles saw the same periodic comet during their reign on earth [64].

Sport and leisure

We have already noted the impact that the availability and speed of railways had in increasing and regimenting tourism. The increased importance of time also started being reflected in people’s other leisure activities. In England, for example, increased leisure times had been made possible by the half Saturday holiday derived from industrialisation. Together with revived interest in team sports in the English public schools, increased networks of schools that had inter school sporting competitions, and a revival of the idea of the ancient Olympic Games [54], this led to an extraordinary mid-century revival of interest in organised sport and games. This interest was also facilitated the faster transport that enabled people to attend bigger, more organised sporting events, and by higher wages which enabled them to pay to be spectators at them. Activities that formerly were the preserve of professionals and gamblers (such as ‘pedestrianism’) increasingly became popular among the wider population of amateurs. Increasingly, accurate timing started to be a prime consideration in these activities. By the 1850s, the advent of precisely-measured athletic tracks enabled accurate times for each event to be recorded. By 1869, this had been further refined by the development of the stop watch [55]. Together with improved international communications, the novel concept of ‘world records’ began to claim a hold on the public imagination.

Intellectual changes affecting time

During the nineteenth century, firmly-held beliefs about the age of the world – and the beginning of time – came under sustained attack on a number of fronts.

From about 1650, the vast mass of Christians had believed implicitly that time began about 6,000 years ago, when God created heaven and earth. This actually had Biblical sanction; side annotations to Genesis in the King James Version published from 1701 referred to Bishop Ussher’s calculation of the beginning of time as occurring on the night preceding 23 October 4004 BC [56]. Geologists and other ‘scientists’ (as they became known after the word was coined in 1834), seriously challenged this traditional concept as they pushed back their estimates of the age of the earth, in books that sometimes outsold popular novels [57].

The discoveries of the new discipline of astronomy, aided by significant improvements in telescopes [57A], further disrupted conventional notions of time and space. Photographs taken of celestial bodies [58] enabled public appreciation of other worlds, unimaginable distances and ages away. Estimates of the age of the universe grew exponentially to almost unimaginable levels. The need to express these incredible distances led to the development of the mind-stretching concept of the ‘light year’ in the 1880s. By 1905, the estimated age of the world was up to 1.64 billion years. As the geologist G. P. Scrope commented, ‘the leading idea which is present in all our researches, and which accompanies every fresh observation, the sound which to the ear of the student of Nature seems continually echoed from every part of her works, is – Time! Time! Time!’[59].

For many, all this was deeply unsettling. As Gould comments, ‘[W]hat could be more comforting, what more convenient for human domination, that the traditional concept of a young earth, ruled by human will within days of its origin. What more threatening, by contrast, [was] the notion of an almost incomprehensible immensity, with human habitation restricted to a millimicrosecond at the very end! [60]

Even more challenging implications of this immense time-scale became shockingly evident with the publication of Darwin’s On The Origin of Species in 1859. A vast age for the earth provided a feasible time frame for the operation of the Darwinian theory of evolution, presenting a challenge to the public’s conception of themselves as humans, as well as to their Christian faith [61]. Previously-held concepts of the immutability of species over time also suffered major challenges with the increasing discoveries of fossils of long-extinct life forms, which scientists used to establish a chronology of rock strata which suggested an immense history of progressive change. The significance of mutability was enormous. It meant that the future seemed much less predictable, as it could no longer be assumed that things would stay as they were in the present. Darwin himself said that stating his belief that species were not immutable was ‘like confessing to a murder’[62].

Some appreciation of the time-confusion that many would have felt was reflected in a Punch cartoon (Fig 7), inspired by the re-appearance in 1861 of the ‘Great Comet’[63]. The cartoon, The Age of the Comet Ascertained to a Nicety, shows ‘antediluvian’ dinosaurs peering through telescopes as they ‘recognise an old acquaintance of 1372’, based on the fanciful idea that the reptiles saw the same periodic comet during their reign on earth [64].

In the area of physics, too, the traditional understanding of the absolute nature of time was challenged, notably by Poincaré in France. Later, and more radically, Einstein’s development of the concept of relative time meant that time must speed up or slow down depending on how fast one thing is moving relative to something else. Like so many other previous certainties, the concept of a universal ‘now’ or a ‘universally audible tick-tock’ was starting to look more and more like a fiction [65].

Radical thoughts about time were also afoot in the ‘softer’ sciences. Around the turn of the century, the philosopher Bergson was attracting massive crowds to his weekly lectures, distinguishing himself by being placed on the Vatican Index for his controversial views on time. According to his concept of durée, time is measured subjectively, as it is experienced, not by what the clock says. On this basis, the future therefore does not really exist, and each moment carries within it the entire flow of the past [66].

In psychology, too, traditional concepts of time were challenged by an obsession with the assumed importance of dreams, arising from the popularisation of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams (1902). In dreams, time undergoes irrational shifts and dislocations. Past, present and future cease to lose their differentiation, as the dreamer experiences a mental form of time travel. These concepts also had parallels in the concept, popularised by William James, of a ‘stream of consciousness’[67]. James also characterised high-level creative thought as involving not ‘thoughts of concrete things patiently following one another’, but instead a seething cauldron of ideas ‘where partnerships can be joined or loosened in an instant, treadmill routine is unknown, and the unexpected seems the only law’ [68].

Additional new ways of thinking about time also became popular. In the 1850s, for example, the idea of the irreversible ‘Arrow of Time’ began entering the public consciousness. This idea became associated with the elusive concept of ‘entropy’, a term first coined in 1865 [69], which postulated that as one goes forwards in time, everything tends to lose energy and therefore disintegrates into lesser degrees of orderliness [70]. When combined with the increasingly-voguish idea that the universe would continue indefinitely – instead of ending with the Apocalypse – this was seen by some as leading inevitably to the ‘abominable desolation’ of a future world, of the type later portrayed in H G Wells’ The Time Machine. The further idea that, in theory, entropy (and therefore time) may itself be reversed [71] added additional confusion. Later, the concept of a ‘fourth dimension’, variously interpreted as temporal or spatial, entered intellectual and artistic circles, influencing artists such as Duchamp, who was intensely interested in the concept of a time continuum [72].

[End of Part 1]

Now go to:

Part 2: The 'new' time in literature

Part 3: The 'new' time in painting

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014

We welcome your comments on this article

End notes for Part 1

1. Jacques Le Goff (transl Julia Barrow), Medieval Civilisation 400-1500, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1989 at 165; Frugoni, C, Inventions of the Middle Ages, Folio Society, London, 2007 at 41.

2. Le Goff, op cit, at 174.

3. Whitrow, G J, Time in History, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1988 at 82.

4. Lippincott, K, and Ors, The Story of Time, Merrell Holberton (in association with the National Maritime Museum), London, 2003 at 174.

5. These expressions of the passage of time were actually exceptions to traditional academic theory (as stated by Lessing in 1766), under which painting was viewed as a spatial art, as distinct from a temporal art such as poetry (Kern, S, The Culture of Time and Space 1880-1918, Harvard University Press, 1983 at 194). Under this theory, painting should therefore not be concerned with a passage through time; instead, it must express the ‘purity of the moment’ – the moment that distilled the essence of the subject depicted (House, J, ‘Seasons and Moments – Time and Nineteenth-Century Art’, in Lippincott, op cit, at 194).

6. Ades, D, ‘Art and Time in the Twentieth Century’ in Lippincott, op cit, at 203.

7. Photography is generally taken to have been invented in 1839, when the invention was publicly announced and the commercially-produced ‘daguerreotype’ became publicly available. Earlier prototypes had been developed in the 1820s by Niepce. Other processes for the reproduction of images, without the crucial chemical fixing, had long been available through the use of the simple ‘camera obscura’, and the more complex ‘camera lucida’ patented in 1807.

8. The many other ways in which photography may have impacted on art are outside the scope of our discussion here. At a mechanical level, of course, the speed and apparent accuracy of the photographic process, compared to the labour-intensive work of making a painting, meant that photographs played a useful role as time saver or working aid for many artists, particularly in portraits, paintings of exotica, and paintings where scientific precision was important. For more details, see our article Early influences of photography.

9. All human eyes, it seems, except for Leonardo da Vinci’s. With the aid of his anatomical studies, Leonardo was evidently able to discern the individual movements of pigeons’ wings in flight almost 400 years before the introduction of chronophotography: Shlain, L, Art and Physics: Parallel Visions in Space, Time and Light, William Morrow & Co, New York 1991 at 433; Leonardo da Vinci, The Codex on the Flight of Birds, 1505.

10. Feldman, E B, Varieties of Visual Experience, Prentice Hall Inc, New York, 4 edn 1992 at 432, 438.

11. Johnson, D, ‘Confluence and Influence: Photography and the Japanese Print in 1850’, in K. S. Champa (ed) The Rise of Landscape Painting in France: Corot to Monet, Manchester N.H, Currier Gallery of Art, 1991 at 88.

12. Szarkowski, J, The Photographer’s Eye, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2007.

13. Eggum, A (transl Holm, B), Munch and Photography, Yale University Press, New Haven/London, 1989, at 32.

14. Further impetus to this movement was provided by the horrific death tolls in the American Civil War, the Franco Prussian War and the Paris Commune. In many cases, photographs became grieving families’ only tangible link with their departed ones. The appeal to such people of photographs that seemed to show those persons as still ‘living’ is obvious.

15. Jolly, M, Faces of the Living Dead: the Belief in Spirit Photography, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2006 at 8. Jolly also makes the point that photography stops an image of a living person dead in its tracks, and peels that frozen image way from them. In this sense, all portrait photographs are spirit photographs because they allow us to see people as they lived in the past.

16. Sontag, S, On Photography, Penguin Books, Middlesex, 1977 at 86.

17. Hepworth, C, The ABC of the Cinematograph, Hazel, Watson and Viney, London,1897 at 105, cited in Puttnam, D, The Undeclared War: The Struggle for Control of the World’s Film Industry, Harper/Collins, London 1997 at 28.

17A. Quotations from film director Dziga Vertov cited in Berger, J, Ways of Seeing, BBC/Penguin Books, London, 1971 at 17.

18. Puttnam, D, The Undeclared War: The Struggle for Control of the World’s Film Industry, Harper/Collins, London 1997, at 18.

19. Puttnam, op cit, at 18.

20. Doane, MA, The Emergence of Cinematic Time: modernity, contingency, the archive, Harvard University Press, 2002 at 172.

21. Whitrow, op cit, at 160.

22. The top speed of locomotives was over 60 mph – six times faster than a stage-coach (Freeman M, Railways and the Victorian Imagination, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1999 at 82). In America, the introduction of lifts, or ‘elevators’, in the latter part of the nineteenth century would also have provided a thrillingly rapid alternative to walking up (or down) stairs. In conjunction with the telephone, elevators helped make skyscrapers feasible.

23. Smiles, S, The Life of George Stephenson, John Murray, 1905 p vii. Quoted in Klingender, FD, Art and the Industrial Revolution, Granada Publishing Ltd, London, 1968, at 122.

24. Whitrow, op cit, at 160.

25. Its first recorded use, in 1837, was in Dickens’ The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, ch 31. The original usage did not, however, necessarily have the same derisory overtones that it acquired later.

25A. Greg, W R, "Life at High Pressure", Birmingham Review article quoted in the Sydney Morning Herald 7 May 1875.

26. Schivelbusch, W, The Railway Journey: Trains and Travel in the 19th Century, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1979 at 41.

27. Solnit, R, ‘The Annihilation of Time and Space’, New England Review, Vol 24 No 1 (Winter 2003) 5; see also generally the same author's River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West, Penguin Books, London, 2003. Ulysses S. Grant, with a sense of amazement typical of most early rail travellers, wrote, ‘We travelled at least eighteen miles an hour when at full speed, and made the whole distance averaging as much as twelve miles an hour’.

28. Spate, V, Claude Monet: The Colour of Time,Thames and Hudson, London, 1992 at 102: Hughes, R, The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Change, Thames and Hudson, London 1991 (revd edn) at 12.

28A. Thackeray, W M, "De Juventute" in The Roundabour Papers, 1863.

29. Klingender, FD, Art and the Industrial Revolution, Granada Publishing Ltd, London, 1968, at 123

30. Freeman M, Railways and the Victorian Imagination, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1999, at 223, quoting Edward Stanley; Klingender, op cit, at 123.

31. Gleick, J, Faster: the Acceleration of Just About Everything, Little, Brown and Company, London, 1999 at 44.

32. Schivelbusch, W, The Railway Journey: Trains and Travel in the 19th Century. Basil Blackwelll, Oxford, 1979, at 48.

33. Smiles, S, The Life of George Stephenson, John Murray, 1905, in Klingender, op cit, at 122.

34. Gleick (Faster), op cit, at 45.

34A. The Railway Traveller's Handy Book of Hints, Suggestions and Advice, Lockwood & Co, London, 1862 at 28 (reprinted 2012 by Old House, Oxford).

35. Jarvis, J, Exploring the Modern: Patterns of Western Culture and Civilisation, Blackwell Publications, Maiden Mass, 1998 at 208.

36. By 1900, the universal diffusion of pocket watches had an impact in ‘accelerating modern life by instilling a sense of punctuality and exactness’ (Solnit, op cit).

37. Schivelbusch, op cit, at 48

38. Gleick (Faster), op cit, at 45; Galison, P. Einstein’s Clocks Poincare’s Maps: Empires of Time, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 2003 at 107. For the development of standard time, see Blaise, C, Time Lord: Sir Sandford Fleming and the Creation of Standard Time, Phoenix, London 2001.

39. Strictly, ‘Big Pen’ refers to the name given to the Great Bell attached to the Great Clock of Westminster in the Clock Tower at the Palace of Westminster, but in common parlance it is often used to include the clock and even the tower itself.

40. Flanders, J, Consuming Passions: Leisure and Pleasure in Victorian Britain, HarperPress, 2006.

41. Dombey and Son (1848) at 185.

42. Beard, GM, American Nervousness, its Causes and Consequences, Putnam, 1881, at 103 see also Harrington, R. "The Neuroses of the Railway", History Today, vol 44, no 7, July 1994, at 15; Matus, J L, "Trauma, Memory, and Railway Disaster: The Dickensian Connection", Victorian Studies, vol 43, no 3 (2001) at 413-436.

43. Freeman, op cit, at 82. Interestingly, it seems that the word 'worry', previously used in the active sense to mean to torment another (eg the dog worried its prey), changed during the nineteenth century to acquire the meaning of tormenting oneself (Phillips, A, On Kissing, Tickling and Being Bored, Faber and Faber, London, 1993).

44. Whitrow, op cit, at 159.

45. Gleick, J, The Information, Fourth Estate, London, 2011 at 139.

46. Gleick (Faster), op cit, at 35.

47. Watson, P, Ideas: a History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud, Harper Perennial, 2006 at 729.

48. Spate, op cit, at 8.

49. Sutherland J, Introduction to Wilkie Collins, The Moonstone, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1999 at xxiii. By 1860, there were 1,100 newspaper titles in Britain. The number of potential readers was also boosted by increasing literacy rates.

50. The growth was also stimulated by the abolition of the stamp tax (1855) and of the duty on paper (1860).

51. Johnson, P, Mail by Rail - The History of the TPO & Post Office Railway, Ian Allan Publishing, London, 1995.

52. Winchester, S, Krakatoa: the Day the World Exploded, August 27, 1883, HarperCollins, New York, 2003 at 6. It is extraordinary to consider that before the development of the (electric) telegraph in the 1840s, the fastest mode of long-distance human communication was probably the drum-language messages that had been used widely in Africa for some centuries. The first detailed analysis of these messages appears in Carrington, J, The Talking Drums of Africa, Carey Kingsgate, London, 1949.

53. Gleick (Information), op cit, at 148.

54. By Evangelos Zappas, as early as 1856.

55. The first patent was granted to Tag Heuer.

56. This was a rejection of the Aristotelian belief that the earth was eternal. The literal accuracy of Ussher’s view had long been doubted in certain intellectual circles. Eighteenth-century savants such as Kant considered that the real age should be measured in millions of years (Rossi, P, The Birth of Modern Science, Wiley-Blackwall, 2001, ch 13).

57. The key English text was Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1834), notable among other things for its elaboration of the concept of 'deep time'. The term 'scientist' was originally proposed by William Whewell at a British Association debate reported in the Quarterly Review of 1834. By 1840, the term was recognised in the Oxford English Dictionary: Holmes, op cit, at 449-450. For an extraordinarily far-sighted early view, see Benoît de Maillet's palindromically-titled Telliamed, or Conversation between an Indian Philosopher and a French Missionary on the Diminution of the Sea (1748), in which, on the basis of his geologic observations, he postulated a world slowly evolving over 2 billion years, evolution of land creatures from sea creatures, and the natural evolution of humans.

57A. The improvements made by William Herschel from the 1770s onwards were particularly significant: see Holmes, R, The Age of Wonder, Harper Press, London, 2008, ch 2. In one sense, of course, astronomy itself was an exercise in time travel, as people observing far-distant stars were necessarily seeing images of those stars as they had been in the past.

58. The first daguerreotypes of the moon, sun and a remote star were taken between 1840 and 1850. On the sun, see Aczil, AD, Pendulum, Washington Square Press, New York, 2003, at 85.

59. Scrope, GP, The Geology and Extinct Volcanoes of Central France (2nd ed., 1858), 208-9, epigraph in Gould S J, Times Arrow, Time’s Cycle: myth and metaphor in the discovery of geological time, Harvard University Press 1988.

60. Gould, op cit, at 2.

61. Tellingly, the 1867 edition of Figuier’s La Terre Avant le Déluge abandoned the Garden of Eden shown in the first edition, and included dramatic illustrations of savage men and women wearing animal skins and wielding stone axes.

62. Letter to J D Hooker, 11 January 1844 at http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/entry-729, accessed September 2011. On an even larger scale, the astronomical concept of a constantly evolving universe, as distinct from a fixed immutable world, had also been advanced as early as 1785: Holmes, op cit, at 191, 204.

63. Punch 41, July 1861 at 34.

64. The cartoon is unconsciously and poignantly prescient, in view of more recent scientific theories that it was the impact of a giant asteroid crashing on Earth which actually led to the disappearance of the dinosaurs.

65. Einstein’s theory took some years after its publication in 1905 to percolate through to public consciousness: Leibowitz, I R, Hidden Harmony: The Connected Worlds of Physics and Art, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2008. On the connection between Poincaré’s and Einstein’s concepts, see Miller, A, Einstein, Picasso, Space, Time and the Beauty That Causes Havoc, Basic Books, New York, 2001.

66. Bergson’s view that we have an intuitive understanding of time, simultaneity and duration can be contrasted with the views being developed in physics by Poincaré (Galison, op cit, at 32-33).

67. Kern, op cit, at 24.

68. James, W, ‘Great Men, Great Thoughts and the Environment’, lecture published in Atlantic Monthly October 1880.

69. By the physicist Rudolf Clausius.

70. Arnheim. R, Entropy and Art – An Essay on Disorder and Order, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1971 at 8-9.

71. This idea was developed by physicists James Clerk Maxwell and William Thomson (Lord Kelvin).

72. The American medium Henry Slade, in his trial for criminal deception in relation to experiments involving a so-called fourth dimension, was actually defended by some eminent scientists. One of these, Johann Zollner, wrote Transcendental Physics (1879) which, while ridiculed in many quarters, contributed to a surge in popular interest in the fourth dimension that lasted well into the twentieth century.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Art in a Speeded up World", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to Overview

Return to Home

Radical thoughts about time were also afoot in the ‘softer’ sciences. Around the turn of the century, the philosopher Bergson was attracting massive crowds to his weekly lectures, distinguishing himself by being placed on the Vatican Index for his controversial views on time. According to his concept of durée, time is measured subjectively, as it is experienced, not by what the clock says. On this basis, the future therefore does not really exist, and each moment carries within it the entire flow of the past [66].

In psychology, too, traditional concepts of time were challenged by an obsession with the assumed importance of dreams, arising from the popularisation of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams (1902). In dreams, time undergoes irrational shifts and dislocations. Past, present and future cease to lose their differentiation, as the dreamer experiences a mental form of time travel. These concepts also had parallels in the concept, popularised by William James, of a ‘stream of consciousness’[67]. James also characterised high-level creative thought as involving not ‘thoughts of concrete things patiently following one another’, but instead a seething cauldron of ideas ‘where partnerships can be joined or loosened in an instant, treadmill routine is unknown, and the unexpected seems the only law’ [68].

Additional new ways of thinking about time also became popular. In the 1850s, for example, the idea of the irreversible ‘Arrow of Time’ began entering the public consciousness. This idea became associated with the elusive concept of ‘entropy’, a term first coined in 1865 [69], which postulated that as one goes forwards in time, everything tends to lose energy and therefore disintegrates into lesser degrees of orderliness [70]. When combined with the increasingly-voguish idea that the universe would continue indefinitely – instead of ending with the Apocalypse – this was seen by some as leading inevitably to the ‘abominable desolation’ of a future world, of the type later portrayed in H G Wells’ The Time Machine. The further idea that, in theory, entropy (and therefore time) may itself be reversed [71] added additional confusion. Later, the concept of a ‘fourth dimension’, variously interpreted as temporal or spatial, entered intellectual and artistic circles, influencing artists such as Duchamp, who was intensely interested in the concept of a time continuum [72].

[End of Part 1]

Now go to:

Part 2: The 'new' time in literature

Part 3: The 'new' time in painting

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014

We welcome your comments on this article

End notes for Part 1

1. Jacques Le Goff (transl Julia Barrow), Medieval Civilisation 400-1500, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1989 at 165; Frugoni, C, Inventions of the Middle Ages, Folio Society, London, 2007 at 41.

2. Le Goff, op cit, at 174.

3. Whitrow, G J, Time in History, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1988 at 82.

4. Lippincott, K, and Ors, The Story of Time, Merrell Holberton (in association with the National Maritime Museum), London, 2003 at 174.

5. These expressions of the passage of time were actually exceptions to traditional academic theory (as stated by Lessing in 1766), under which painting was viewed as a spatial art, as distinct from a temporal art such as poetry (Kern, S, The Culture of Time and Space 1880-1918, Harvard University Press, 1983 at 194). Under this theory, painting should therefore not be concerned with a passage through time; instead, it must express the ‘purity of the moment’ – the moment that distilled the essence of the subject depicted (House, J, ‘Seasons and Moments – Time and Nineteenth-Century Art’, in Lippincott, op cit, at 194).

6. Ades, D, ‘Art and Time in the Twentieth Century’ in Lippincott, op cit, at 203.

7. Photography is generally taken to have been invented in 1839, when the invention was publicly announced and the commercially-produced ‘daguerreotype’ became publicly available. Earlier prototypes had been developed in the 1820s by Niepce. Other processes for the reproduction of images, without the crucial chemical fixing, had long been available through the use of the simple ‘camera obscura’, and the more complex ‘camera lucida’ patented in 1807.

8. The many other ways in which photography may have impacted on art are outside the scope of our discussion here. At a mechanical level, of course, the speed and apparent accuracy of the photographic process, compared to the labour-intensive work of making a painting, meant that photographs played a useful role as time saver or working aid for many artists, particularly in portraits, paintings of exotica, and paintings where scientific precision was important. For more details, see our article Early influences of photography.

9. All human eyes, it seems, except for Leonardo da Vinci’s. With the aid of his anatomical studies, Leonardo was evidently able to discern the individual movements of pigeons’ wings in flight almost 400 years before the introduction of chronophotography: Shlain, L, Art and Physics: Parallel Visions in Space, Time and Light, William Morrow & Co, New York 1991 at 433; Leonardo da Vinci, The Codex on the Flight of Birds, 1505.

10. Feldman, E B, Varieties of Visual Experience, Prentice Hall Inc, New York, 4 edn 1992 at 432, 438.

11. Johnson, D, ‘Confluence and Influence: Photography and the Japanese Print in 1850’, in K. S. Champa (ed) The Rise of Landscape Painting in France: Corot to Monet, Manchester N.H, Currier Gallery of Art, 1991 at 88.

12. Szarkowski, J, The Photographer’s Eye, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2007.

13. Eggum, A (transl Holm, B), Munch and Photography, Yale University Press, New Haven/London, 1989, at 32.

14. Further impetus to this movement was provided by the horrific death tolls in the American Civil War, the Franco Prussian War and the Paris Commune. In many cases, photographs became grieving families’ only tangible link with their departed ones. The appeal to such people of photographs that seemed to show those persons as still ‘living’ is obvious.

15. Jolly, M, Faces of the Living Dead: the Belief in Spirit Photography, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2006 at 8. Jolly also makes the point that photography stops an image of a living person dead in its tracks, and peels that frozen image way from them. In this sense, all portrait photographs are spirit photographs because they allow us to see people as they lived in the past.

16. Sontag, S, On Photography, Penguin Books, Middlesex, 1977 at 86.

17. Hepworth, C, The ABC of the Cinematograph, Hazel, Watson and Viney, London,1897 at 105, cited in Puttnam, D, The Undeclared War: The Struggle for Control of the World’s Film Industry, Harper/Collins, London 1997 at 28.

17A. Quotations from film director Dziga Vertov cited in Berger, J, Ways of Seeing, BBC/Penguin Books, London, 1971 at 17.

18. Puttnam, D, The Undeclared War: The Struggle for Control of the World’s Film Industry, Harper/Collins, London 1997, at 18.

19. Puttnam, op cit, at 18.

20. Doane, MA, The Emergence of Cinematic Time: modernity, contingency, the archive, Harvard University Press, 2002 at 172.

21. Whitrow, op cit, at 160.

22. The top speed of locomotives was over 60 mph – six times faster than a stage-coach (Freeman M, Railways and the Victorian Imagination, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1999 at 82). In America, the introduction of lifts, or ‘elevators’, in the latter part of the nineteenth century would also have provided a thrillingly rapid alternative to walking up (or down) stairs. In conjunction with the telephone, elevators helped make skyscrapers feasible.

23. Smiles, S, The Life of George Stephenson, John Murray, 1905 p vii. Quoted in Klingender, FD, Art and the Industrial Revolution, Granada Publishing Ltd, London, 1968, at 122.

24. Whitrow, op cit, at 160.

25. Its first recorded use, in 1837, was in Dickens’ The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, ch 31. The original usage did not, however, necessarily have the same derisory overtones that it acquired later.

25A. Greg, W R, "Life at High Pressure", Birmingham Review article quoted in the Sydney Morning Herald 7 May 1875.

26. Schivelbusch, W, The Railway Journey: Trains and Travel in the 19th Century, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1979 at 41.

27. Solnit, R, ‘The Annihilation of Time and Space’, New England Review, Vol 24 No 1 (Winter 2003) 5; see also generally the same author's River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West, Penguin Books, London, 2003. Ulysses S. Grant, with a sense of amazement typical of most early rail travellers, wrote, ‘We travelled at least eighteen miles an hour when at full speed, and made the whole distance averaging as much as twelve miles an hour’.

28. Spate, V, Claude Monet: The Colour of Time,Thames and Hudson, London, 1992 at 102: Hughes, R, The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Change, Thames and Hudson, London 1991 (revd edn) at 12.

28A. Thackeray, W M, "De Juventute" in The Roundabour Papers, 1863.

29. Klingender, FD, Art and the Industrial Revolution, Granada Publishing Ltd, London, 1968, at 123

30. Freeman M, Railways and the Victorian Imagination, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1999, at 223, quoting Edward Stanley; Klingender, op cit, at 123.

31. Gleick, J, Faster: the Acceleration of Just About Everything, Little, Brown and Company, London, 1999 at 44.

32. Schivelbusch, W, The Railway Journey: Trains and Travel in the 19th Century. Basil Blackwelll, Oxford, 1979, at 48.

33. Smiles, S, The Life of George Stephenson, John Murray, 1905, in Klingender, op cit, at 122.

34. Gleick (Faster), op cit, at 45.

34A. The Railway Traveller's Handy Book of Hints, Suggestions and Advice, Lockwood & Co, London, 1862 at 28 (reprinted 2012 by Old House, Oxford).

35. Jarvis, J, Exploring the Modern: Patterns of Western Culture and Civilisation, Blackwell Publications, Maiden Mass, 1998 at 208.

36. By 1900, the universal diffusion of pocket watches had an impact in ‘accelerating modern life by instilling a sense of punctuality and exactness’ (Solnit, op cit).

37. Schivelbusch, op cit, at 48

38. Gleick (Faster), op cit, at 45; Galison, P. Einstein’s Clocks Poincare’s Maps: Empires of Time, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 2003 at 107. For the development of standard time, see Blaise, C, Time Lord: Sir Sandford Fleming and the Creation of Standard Time, Phoenix, London 2001.

39. Strictly, ‘Big Pen’ refers to the name given to the Great Bell attached to the Great Clock of Westminster in the Clock Tower at the Palace of Westminster, but in common parlance it is often used to include the clock and even the tower itself.

40. Flanders, J, Consuming Passions: Leisure and Pleasure in Victorian Britain, HarperPress, 2006.

41. Dombey and Son (1848) at 185.

42. Beard, GM, American Nervousness, its Causes and Consequences, Putnam, 1881, at 103 see also Harrington, R. "The Neuroses of the Railway", History Today, vol 44, no 7, July 1994, at 15; Matus, J L, "Trauma, Memory, and Railway Disaster: The Dickensian Connection", Victorian Studies, vol 43, no 3 (2001) at 413-436.

43. Freeman, op cit, at 82. Interestingly, it seems that the word 'worry', previously used in the active sense to mean to torment another (eg the dog worried its prey), changed during the nineteenth century to acquire the meaning of tormenting oneself (Phillips, A, On Kissing, Tickling and Being Bored, Faber and Faber, London, 1993).

44. Whitrow, op cit, at 159.

45. Gleick, J, The Information, Fourth Estate, London, 2011 at 139.

46. Gleick (Faster), op cit, at 35.

47. Watson, P, Ideas: a History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud, Harper Perennial, 2006 at 729.

48. Spate, op cit, at 8.

49. Sutherland J, Introduction to Wilkie Collins, The Moonstone, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1999 at xxiii. By 1860, there were 1,100 newspaper titles in Britain. The number of potential readers was also boosted by increasing literacy rates.

50. The growth was also stimulated by the abolition of the stamp tax (1855) and of the duty on paper (1860).

51. Johnson, P, Mail by Rail - The History of the TPO & Post Office Railway, Ian Allan Publishing, London, 1995.

52. Winchester, S, Krakatoa: the Day the World Exploded, August 27, 1883, HarperCollins, New York, 2003 at 6. It is extraordinary to consider that before the development of the (electric) telegraph in the 1840s, the fastest mode of long-distance human communication was probably the drum-language messages that had been used widely in Africa for some centuries. The first detailed analysis of these messages appears in Carrington, J, The Talking Drums of Africa, Carey Kingsgate, London, 1949.

53. Gleick (Information), op cit, at 148.

54. By Evangelos Zappas, as early as 1856.

55. The first patent was granted to Tag Heuer.

56. This was a rejection of the Aristotelian belief that the earth was eternal. The literal accuracy of Ussher’s view had long been doubted in certain intellectual circles. Eighteenth-century savants such as Kant considered that the real age should be measured in millions of years (Rossi, P, The Birth of Modern Science, Wiley-Blackwall, 2001, ch 13).

57. The key English text was Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1834), notable among other things for its elaboration of the concept of 'deep time'. The term 'scientist' was originally proposed by William Whewell at a British Association debate reported in the Quarterly Review of 1834. By 1840, the term was recognised in the Oxford English Dictionary: Holmes, op cit, at 449-450. For an extraordinarily far-sighted early view, see Benoît de Maillet's palindromically-titled Telliamed, or Conversation between an Indian Philosopher and a French Missionary on the Diminution of the Sea (1748), in which, on the basis of his geologic observations, he postulated a world slowly evolving over 2 billion years, evolution of land creatures from sea creatures, and the natural evolution of humans.

57A. The improvements made by William Herschel from the 1770s onwards were particularly significant: see Holmes, R, The Age of Wonder, Harper Press, London, 2008, ch 2. In one sense, of course, astronomy itself was an exercise in time travel, as people observing far-distant stars were necessarily seeing images of those stars as they had been in the past.

58. The first daguerreotypes of the moon, sun and a remote star were taken between 1840 and 1850. On the sun, see Aczil, AD, Pendulum, Washington Square Press, New York, 2003, at 85.

59. Scrope, GP, The Geology and Extinct Volcanoes of Central France (2nd ed., 1858), 208-9, epigraph in Gould S J, Times Arrow, Time’s Cycle: myth and metaphor in the discovery of geological time, Harvard University Press 1988.

60. Gould, op cit, at 2.

61. Tellingly, the 1867 edition of Figuier’s La Terre Avant le Déluge abandoned the Garden of Eden shown in the first edition, and included dramatic illustrations of savage men and women wearing animal skins and wielding stone axes.

62. Letter to J D Hooker, 11 January 1844 at http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/entry-729, accessed September 2011. On an even larger scale, the astronomical concept of a constantly evolving universe, as distinct from a fixed immutable world, had also been advanced as early as 1785: Holmes, op cit, at 191, 204.

63. Punch 41, July 1861 at 34.

64. The cartoon is unconsciously and poignantly prescient, in view of more recent scientific theories that it was the impact of a giant asteroid crashing on Earth which actually led to the disappearance of the dinosaurs.

65. Einstein’s theory took some years after its publication in 1905 to percolate through to public consciousness: Leibowitz, I R, Hidden Harmony: The Connected Worlds of Physics and Art, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2008. On the connection between Poincaré’s and Einstein’s concepts, see Miller, A, Einstein, Picasso, Space, Time and the Beauty That Causes Havoc, Basic Books, New York, 2001.

66. Bergson’s view that we have an intuitive understanding of time, simultaneity and duration can be contrasted with the views being developed in physics by Poincaré (Galison, op cit, at 32-33).

67. Kern, op cit, at 24.

68. James, W, ‘Great Men, Great Thoughts and the Environment’, lecture published in Atlantic Monthly October 1880.

69. By the physicist Rudolf Clausius.

70. Arnheim. R, Entropy and Art – An Essay on Disorder and Order, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1971 at 8-9.

71. This idea was developed by physicists James Clerk Maxwell and William Thomson (Lord Kelvin).