The floating pleasure worlds of Paris and Edo

|

Any work of art is a product of a number of factors – the era and society in which it is produced, the talent and inclinations of the artist, the artistic tradition upon which the artist draws, and the limitations and scope of the medium and technology used.

|

For more on food and art ----------------------------------------------------

|

This article examines two works by artists who were working at the peak of their form. Both works have a similar subject matter – a lively social gathering – but were created in different media, in different cultures on opposite sides of the world, almost one hundred years apart. The result is two works that, outwardly at least, appear strikingly different. Yet, intriguingly, the closer one looks, the more similarities emerge.

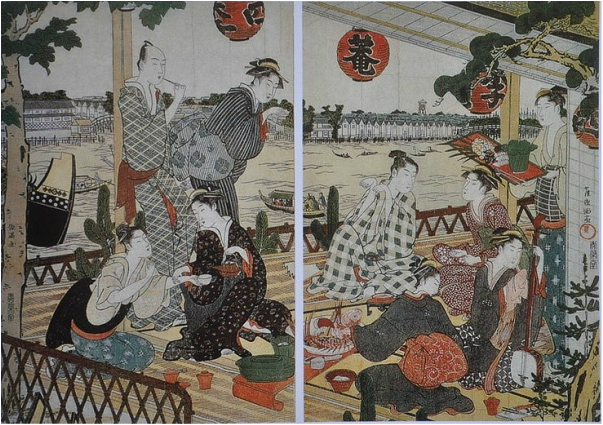

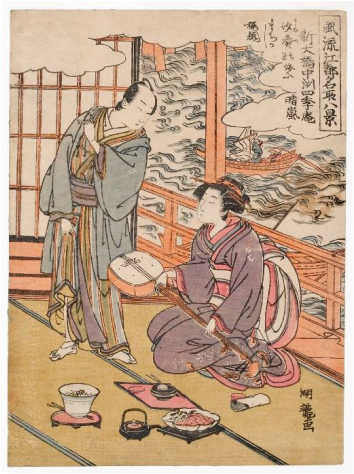

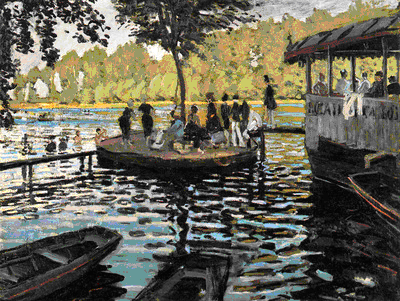

The works in question are The Shikian Restaurant (c 1787)[1], a coloured diptych woodblock print by the Japanese artist Kubo Shumman [2], and The Luncheon of the Boating Party (1881) [3], an oil painting by the French artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir [4].

The works in question are The Shikian Restaurant (c 1787)[1], a coloured diptych woodblock print by the Japanese artist Kubo Shumman [2], and The Luncheon of the Boating Party (1881) [3], an oil painting by the French artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir [4].

Two floating worlds

Kumman’s The Shikian Restaurant is a picture of Japan’s “Floating World”. The Floating World (ukiyo) was originally a Buddhist term expressive of the transience of life. However, by the late seventeenth century it had acquired more positive connotations. Instead of the transient world of sorrows, it came to refer to the transient world of pleasures [5]. This new mood was memorably expressed as one of “living only for the moment… singing songs, drinking wine, and diverting ourselves just in floating, floating… like a gourd floating along with the river current”[6].

By a striking coincidence, Renoir too had adopted remarkably similar language in explaining his own well-defined philosophy of life. “One is merely a cork,” he said, “You must let yourself go along in life like a cork in the current of a stream” [7]. Speaking of his feelings at the time of painting the Luncheon, he said, “We still had life ahead of us; we denied ourselves nothing… Life was a never ending celebration!”[8]

These twin images of pleasure-seeking gourds or corks bobbing in streams are, of course, metaphorical. But they echo more literal connections that have often been drawn between pleasure and water. The Japanese architectural historian Hidenobu Jinnai noted that a freedom from social norms had, since ancient times, been enjoyed in places connected with water, and that entertainment quarters were commonly situated near bridges [9]. The historian Amino Yoshihiko similarly observed that in medieval Japan, the places where itinerant entertainers gathered, such as riverbanks, were considered to be exempt from social norms. The “distorted remains” of this tradition survived in marginal urban precincts as the brothel quarters and theatres [10].

In France, too, the Seine has been described as being as “symbolically potent”, with a similarly prominent role in arts and literature as a symbol of pleasure, love and intrigue [11]. In particular, towards the end of the nineteenth century, the river became a focus of the Parisian preoccupation with entertainment, heightened by an easing of earlier restrictions on public performances [12]. Some of the Impressionists, such as Caillebote, Monet and Sisley became almost obsessive in their depictions of the Seine as a focus for images of contemporary life. These scenes typically featured urbanites enjoying themselves in the countryside with adult, tipsy informality, unequal mixtures of men and women and the absence of children [13].

By a striking coincidence, Renoir too had adopted remarkably similar language in explaining his own well-defined philosophy of life. “One is merely a cork,” he said, “You must let yourself go along in life like a cork in the current of a stream” [7]. Speaking of his feelings at the time of painting the Luncheon, he said, “We still had life ahead of us; we denied ourselves nothing… Life was a never ending celebration!”[8]

These twin images of pleasure-seeking gourds or corks bobbing in streams are, of course, metaphorical. But they echo more literal connections that have often been drawn between pleasure and water. The Japanese architectural historian Hidenobu Jinnai noted that a freedom from social norms had, since ancient times, been enjoyed in places connected with water, and that entertainment quarters were commonly situated near bridges [9]. The historian Amino Yoshihiko similarly observed that in medieval Japan, the places where itinerant entertainers gathered, such as riverbanks, were considered to be exempt from social norms. The “distorted remains” of this tradition survived in marginal urban precincts as the brothel quarters and theatres [10].

In France, too, the Seine has been described as being as “symbolically potent”, with a similarly prominent role in arts and literature as a symbol of pleasure, love and intrigue [11]. In particular, towards the end of the nineteenth century, the river became a focus of the Parisian preoccupation with entertainment, heightened by an easing of earlier restrictions on public performances [12]. Some of the Impressionists, such as Caillebote, Monet and Sisley became almost obsessive in their depictions of the Seine as a focus for images of contemporary life. These scenes typically featured urbanites enjoying themselves in the countryside with adult, tipsy informality, unequal mixtures of men and women and the absence of children [13].

Nakasu and Chatou

In eighteenth century Edo (now Tokyo), the Floating World concepts of high living and extravagance were focused on the Kabuki theatre district and the “pleasure” quarters that were devoted largely to prostitution. Sex was a major industry in Japan, fuelled in part by Edo’s culture of consumption [14], a significant preponderance of men [15], and a growing class of urban merchants who, due to sumptuary laws and their low social status [16], had money but few outlets for spending it, other than on arts and entertainment.

Kumman’s painting (Figs 1 and 2) depicts an establishment in one of these pleasure quarters. Its setting is the real-life restaurant, the Shikian (or “Four Seasons Hermitage”) situated in a small town (Nakasu) [17] near a fork of a major river (the Sumida), a few miles downstream from the capital (Edo). Nakasu was a stretch of filled-in land jutting out into the river to form a virtual island in an area known for flooding. In fact, it was almost literally a floating world.

Kumman’s painting (Figs 1 and 2) depicts an establishment in one of these pleasure quarters. Its setting is the real-life restaurant, the Shikian (or “Four Seasons Hermitage”) situated in a small town (Nakasu) [17] near a fork of a major river (the Sumida), a few miles downstream from the capital (Edo). Nakasu was a stretch of filled-in land jutting out into the river to form a virtual island in an area known for flooding. In fact, it was almost literally a floating world.

Nakasu was an example of the unlicensed pleasure quarters that developed in outlying areas in competition to the officially licensed Yoshiwara [18]. It was popular for its teahouses, restaurants, boating and – above all – for commercial sex, both institutionalised and freelance. By 1779, there were reportedly 18 restaurants, 93 teahouses, 14 boathouses and at least 27 geisha in Nakasu, making it one of the larger concentrations of famous restaurants and teahouses in Japan [19].

Nakasu’s real boom period, however, began from 1787, when there was a major fire in the Yoshiwara, prompting some Yoshiwara establishment proprietors to temporarily transfer in Nakasu [20]. Here, courtesans and others could ply their trade, and a wider range of customers enjoy it, free of the complex and burdensome rituals and procedures, and the sometimes crippling expense, of the Yoshiwara. Standards were lower – Nakasu courtesans were not so choosy in picking clients, and the establishments were less comfortable and less classy [21].

Nakasu’s real boom period, however, began from 1787, when there was a major fire in the Yoshiwara, prompting some Yoshiwara establishment proprietors to temporarily transfer in Nakasu [20]. Here, courtesans and others could ply their trade, and a wider range of customers enjoy it, free of the complex and burdensome rituals and procedures, and the sometimes crippling expense, of the Yoshiwara. Standards were lower – Nakasu courtesans were not so choosy in picking clients, and the establishments were less comfortable and less classy [21].

The Shikian stood out as probably the best known of Nakasu’s restaurants, famous for its range of food, including fish supplied from its own “live tank” pond. It attracted various ranks of society, including artists and poets [22]. One contemporary account describes the Shikian as a venue for lords and commoners of all types – “some up-to- date, others old fashioned, boorish types, aficionados, pleasure seekers, courtesans, geisha, all mixing together. There are many rooms, but they are never empty.” [23]

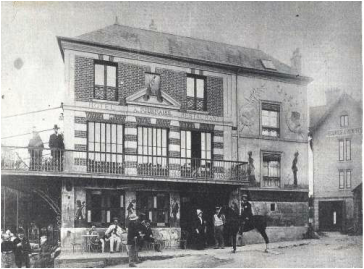

This setting has many close similarities to the setting of Renoir’s work (fig 3A). Precisely matching the Shikian, the Luncheon is also set in a real-life restaurant (this one called La Maison Fournaise), situated in a small village/town (Chatou), on an island in a fork of a major river (the Seine), and in a popular spot for boating, a few miles downstream from the capital (Paris).

This setting has many close similarities to the setting of Renoir’s work (fig 3A). Precisely matching the Shikian, the Luncheon is also set in a real-life restaurant (this one called La Maison Fournaise), situated in a small village/town (Chatou), on an island in a fork of a major river (the Seine), and in a popular spot for boating, a few miles downstream from the capital (Paris).

The Fournaise, with its accompanying small hotel and boat rental facilities (Fig 4), had recently been established to take advantage of the new tourist trade, fuelled by the new railway connection from Paris [24]. Just as with the Shikian, there was a wide mix of customers. Parisians of all classes – shopgirls, clerks [25], businessmen, society women, artists, actresses, writers and critics – thronged there on Sundays to throw off their city restraints, to enjoy the pleasures of boating, dancing, cafes and, for many, the possibility of casual sex [26}.

Just downstream, and downmarket, from the Maison Fournaise was La Grenouillere (the “Frog Pond”), one of the best-known pick-up joints in Chatou. Again, it was almost literally a floating world. Supposedly named after the fast women (“frogs”) that hung out there, this venue became famous as the subject of paintings by Monet and Renoir in the late 1860s (fig 5). It was variously described as a “jolly, vulgar place”, with “a pervading atmosphere of love-making” [27]; “a rustic little place for rendezvous by a very frivolous society”; a place where “if a man go there alone, he returns in the company of at least one person” [28]; and the nineteenth-century equivalent of a singles bar [29].

For all the similarities between Chatou and Nakasu, however, there was a difference of degree. Although both were places where people came to be entertained, to relax, and form liaisons in an atmosphere of pleasure seeking, the economy of Chatou was not based predominantly on institutionalised or commercial sex. It was perfectly possible, and very common, to go to Chatou entirely for “innocent” entertainment [30].

Subject matter and composition

In Shumman’s work, a party is in progress in a partly open area of the Shikian. Everyone seems to have already dined – sake and a large sea bream [31] have been served, and a maid brings in another tray with raw fish and other delicacies. The room has probably been engaged by the two young men in light summer robes.On the right, two women, probably geisha, tune their shamisen ready to play music [32]. The people interact in small groups and, in the background, boats sail on the river.

Renoir’s work, too, shows a party in progress in the partly open terrace of the restaurant. Again, everyone seems to have already dined – bunches of grapes, half-empty wine bottles and the remains of a meal are scattered on the rumpled tablecloth. Most of the people are in small groups and, again, in the background, boats sail on the river.

These similarities in subject matter are surpassed by some remarkable similarities in composition of the two works. Both feature oblique close-up views, as if the viewer were actually in a corner inside the restaurant [33]. In both, the viewer looks out across the social action to the river, to the waterfront beyond, and ultimately to a partly obscured bridge crossing the river.

The waterside balustrade of each restaurant is set on a sharp diagonal running upwards from the left foreground. This angle maximises the space available for the depiction of the numerous characters (and, in the Shikian, enables Shumman to avoid the appearance of having a procession of people stationed across a horizontal, stage-like setting). In both works, the angle is mirrored by the far shoreline, and is emphasised by the verticals of the receding pillars or supports. It is also echoed in the positioning of the figures – in the Shikian, by the diagonal from the sitting waitress at bottom left to the similarly-clad waitress standing at top right, and in the Luncheon by the diagonal from the girl with the dog toward the main group of people on the right.

Balancing diagonals are also created – in the Shikian by the angle of the front fence, and the angle from the woman on the left who appears to be pointing to the geisha on the right; and in the Luncheon, by the front edge of the table and the angle from the boatman standing top left to the similarly-clad boatman sitting in the right foreground.

On the left of both works, a man lounges against a balustrade or pillar, idly surveying the busy scene. In each work, the line of his back is gracefully continued by the curved back of the woman seated in the left foreground. A corresponding curve appears in the right foreground, formed by the curve of the singleted boatman’s back and the leaning man’s arm (in the Luncheon), and by the line of the two women sitting nearest the standing waitress (in the Shikian). In both works, these gentle interactive curves provide a balanced sense of movement while at the same time suggesting the relaxation of the participants.

Both works are framed at the top by the angled line of a ceiling. This is a reminder that the setting is a building, not a deck, though it is softened in each case by foliage, heavily stylised in the case of Shikian. This top framing also has the effect of enclosing the group and making the scene more intimate. The round shapes of Shumman’s red lanterns hanging from the edge of the roof are reflected in the scalloped edge of Renoir’s striped apricot awning [34].

At the edges, both works are cropped, though in different ways. In the Shikian, there is radical cropping of the tree and the boat on the left, but all of the main characters are shown in full. This probably reflects the importance placed on giving maximum exposure to clothing. In the Luncheon, on the other hand, there is a more photographic-style cropping – legs are cropped from the bottom edge, and a woman’s back from the right edge – as if to ensure that as many faces as possible can get into the picture.

In both works, gesture and touch are also used to reinforce elegant lines and unite groups. In the Shikian, the standing man at left is, rather unobtrusively, holding hands with the standing woman. She herself appears to be pointing toward the two geisha in the right foreground, who are linked by their matching kimonos. The seated couple in the left foreground are linked literally and harmoniously by the touch of hand on arm. The other couple are engaging in an interplay of hand gestures in playing their game [35].

In the Luncheon, similarly, gestures unify the composition and also strengthen the impression of intimacy. The hand of the woman in the right foreground curls intimately round the back of the singleted man’s chair, and is brushed by the hand of the man leaning over her. The hair of the woman in the left foreground brushes the hand of the tall standing man. A man’s hand encircles the waist of the woman on the right who is holding her ears.

The question must be asked at this point whether Renoir may have been influenced by the diagonal lines and radical cropping that was characteristic of the Japanese woodblock prints that burst onto the Paris art scene from the 1860s. These prints undeniably influenced many French artists, including some Impressionists. It seems, however, that Renoir may have remained outside their influence. Although appreciating their distinctive character, he emphatically and rather chauvinistically rejected them as an influence, after reaching the conclusion that “Japanese prints are certainly most interesting, as Japanese prints… that is to say, on condition that they stay in Japan. No people should appreciate what does not belong to their own race, if they don’t want to make themselves ridiculous…” [36].

Nor does there appear to be any evidence that he was subconsciously influenced (or that he was dissembling), though of course this would be difficult to prove one way or the other. Rather, the oblique angle and cropping in Luncheon would appear to be attributable simply to the physical constraints of the balcony setting and the need to fit in all the characters. If we are looking for sources of influence, a more likely candidate is provided by the left foreground of Veronese’s Wedding Feast at Cana (1563). That painting, which Renoir is known to have admired [37], has many similar elements to the Luncheon, including close overlapping of figures, the depiction of the remains of a sumptuous meal, grapes and goblets, and a diagonally positioned white clothed table.

Some important compositional differences between Renoir’s and Shumman’s works should also be noted. The Shikian is a diptych, with each panel being capable of standing on its own, as well as contributing to the overall balance of the whole. This self-containment is assisted by grouping most of the people as couples – the couple holding hands on the left, the two seated women, the two geisha with their shamisen, and the two playing the hand game.

This does not apply in the Luncheon. If that work is divided vertically into two, the left side presents a mysterious view of three people looking in a variety of directions, and the right becomes an unbalanced and oddly crowded scene with the brown suited man looking away out to the left. With a mixture of groups ranging from one person to three persons, the Luncheon only works compositionally because of the interplay across the whole of the picture [38].

Another major compositional difference is, of course, the presence of the two dining tables in the Luncheon. The potential compositional problem posed to Renoir by their size and inertness is solved by a combination of strategies. In the case of the front table, he foreshortens it, so that it appears smaller than in real life, places it at an angle that is not parallel with the balustrade so that it does not appear too narrow, and piles it with bottles and food so as to produce an interesting still life in its own right. The problem of the second table he solves by simply obscuring all except a tiny patch front of the drinking woman. This particular compositional issue does not arise in the Shikian, as dining tables of this type were, of course, not used in Japan. Instead, in the Shikian, the remains of the fish meal are on a low tray (centre foreground, as in Luncheon), and empty cups, chopsticks and napkins are positioned on the tatami matting.

Renoir’s work, too, shows a party in progress in the partly open terrace of the restaurant. Again, everyone seems to have already dined – bunches of grapes, half-empty wine bottles and the remains of a meal are scattered on the rumpled tablecloth. Most of the people are in small groups and, again, in the background, boats sail on the river.

These similarities in subject matter are surpassed by some remarkable similarities in composition of the two works. Both feature oblique close-up views, as if the viewer were actually in a corner inside the restaurant [33]. In both, the viewer looks out across the social action to the river, to the waterfront beyond, and ultimately to a partly obscured bridge crossing the river.

The waterside balustrade of each restaurant is set on a sharp diagonal running upwards from the left foreground. This angle maximises the space available for the depiction of the numerous characters (and, in the Shikian, enables Shumman to avoid the appearance of having a procession of people stationed across a horizontal, stage-like setting). In both works, the angle is mirrored by the far shoreline, and is emphasised by the verticals of the receding pillars or supports. It is also echoed in the positioning of the figures – in the Shikian, by the diagonal from the sitting waitress at bottom left to the similarly-clad waitress standing at top right, and in the Luncheon by the diagonal from the girl with the dog toward the main group of people on the right.

Balancing diagonals are also created – in the Shikian by the angle of the front fence, and the angle from the woman on the left who appears to be pointing to the geisha on the right; and in the Luncheon, by the front edge of the table and the angle from the boatman standing top left to the similarly-clad boatman sitting in the right foreground.

On the left of both works, a man lounges against a balustrade or pillar, idly surveying the busy scene. In each work, the line of his back is gracefully continued by the curved back of the woman seated in the left foreground. A corresponding curve appears in the right foreground, formed by the curve of the singleted boatman’s back and the leaning man’s arm (in the Luncheon), and by the line of the two women sitting nearest the standing waitress (in the Shikian). In both works, these gentle interactive curves provide a balanced sense of movement while at the same time suggesting the relaxation of the participants.

Both works are framed at the top by the angled line of a ceiling. This is a reminder that the setting is a building, not a deck, though it is softened in each case by foliage, heavily stylised in the case of Shikian. This top framing also has the effect of enclosing the group and making the scene more intimate. The round shapes of Shumman’s red lanterns hanging from the edge of the roof are reflected in the scalloped edge of Renoir’s striped apricot awning [34].

At the edges, both works are cropped, though in different ways. In the Shikian, there is radical cropping of the tree and the boat on the left, but all of the main characters are shown in full. This probably reflects the importance placed on giving maximum exposure to clothing. In the Luncheon, on the other hand, there is a more photographic-style cropping – legs are cropped from the bottom edge, and a woman’s back from the right edge – as if to ensure that as many faces as possible can get into the picture.

In both works, gesture and touch are also used to reinforce elegant lines and unite groups. In the Shikian, the standing man at left is, rather unobtrusively, holding hands with the standing woman. She herself appears to be pointing toward the two geisha in the right foreground, who are linked by their matching kimonos. The seated couple in the left foreground are linked literally and harmoniously by the touch of hand on arm. The other couple are engaging in an interplay of hand gestures in playing their game [35].

In the Luncheon, similarly, gestures unify the composition and also strengthen the impression of intimacy. The hand of the woman in the right foreground curls intimately round the back of the singleted man’s chair, and is brushed by the hand of the man leaning over her. The hair of the woman in the left foreground brushes the hand of the tall standing man. A man’s hand encircles the waist of the woman on the right who is holding her ears.

The question must be asked at this point whether Renoir may have been influenced by the diagonal lines and radical cropping that was characteristic of the Japanese woodblock prints that burst onto the Paris art scene from the 1860s. These prints undeniably influenced many French artists, including some Impressionists. It seems, however, that Renoir may have remained outside their influence. Although appreciating their distinctive character, he emphatically and rather chauvinistically rejected them as an influence, after reaching the conclusion that “Japanese prints are certainly most interesting, as Japanese prints… that is to say, on condition that they stay in Japan. No people should appreciate what does not belong to their own race, if they don’t want to make themselves ridiculous…” [36].

Nor does there appear to be any evidence that he was subconsciously influenced (or that he was dissembling), though of course this would be difficult to prove one way or the other. Rather, the oblique angle and cropping in Luncheon would appear to be attributable simply to the physical constraints of the balcony setting and the need to fit in all the characters. If we are looking for sources of influence, a more likely candidate is provided by the left foreground of Veronese’s Wedding Feast at Cana (1563). That painting, which Renoir is known to have admired [37], has many similar elements to the Luncheon, including close overlapping of figures, the depiction of the remains of a sumptuous meal, grapes and goblets, and a diagonally positioned white clothed table.

Some important compositional differences between Renoir’s and Shumman’s works should also be noted. The Shikian is a diptych, with each panel being capable of standing on its own, as well as contributing to the overall balance of the whole. This self-containment is assisted by grouping most of the people as couples – the couple holding hands on the left, the two seated women, the two geisha with their shamisen, and the two playing the hand game.

This does not apply in the Luncheon. If that work is divided vertically into two, the left side presents a mysterious view of three people looking in a variety of directions, and the right becomes an unbalanced and oddly crowded scene with the brown suited man looking away out to the left. With a mixture of groups ranging from one person to three persons, the Luncheon only works compositionally because of the interplay across the whole of the picture [38].

Another major compositional difference is, of course, the presence of the two dining tables in the Luncheon. The potential compositional problem posed to Renoir by their size and inertness is solved by a combination of strategies. In the case of the front table, he foreshortens it, so that it appears smaller than in real life, places it at an angle that is not parallel with the balustrade so that it does not appear too narrow, and piles it with bottles and food so as to produce an interesting still life in its own right. The problem of the second table he solves by simply obscuring all except a tiny patch front of the drinking woman. This particular compositional issue does not arise in the Shikian, as dining tables of this type were, of course, not used in Japan. Instead, in the Shikian, the remains of the fish meal are on a low tray (centre foreground, as in Luncheon), and empty cups, chopsticks and napkins are positioned on the tatami matting.

Depth and perspective

In both works, depth is conveyed by the conventions of perspective, with converging diagonals, and objects and figures becoming smaller as their perceived distance from the viewer increases [39]. However, neither artist is bound by strict accuracy in this regard. In the Shikian, the convergence of the roof and the balustrade is exaggerated, presumably for dramatic effect; the odd angle of the waitress’s tray is a matter of concern; and the perspective of the some of the boats on the river is erratic. Similarly, in the Luncheon, the top-hatted man and his companion seem too small for figures who are only two tables away from the viewer, and there is a marked disproportion in size between the woman leaning on the balustrade and the woman with a glass at her lips, even though they are virtually next to each other.

The major difference between the works in this respect is that Shumman does not use any atmospheric perspective. The outline and detail of the warehouses on the distant shore is as clear as any thing in the foreground [40]. In contrast, Renoir blurs his far outlines – a task more difficult to achieve with prints – and pales his colours to suggest the effect of the intervening atmosphere.

The major difference between the works in this respect is that Shumman does not use any atmospheric perspective. The outline and detail of the warehouses on the distant shore is as clear as any thing in the foreground [40]. In contrast, Renoir blurs his far outlines – a task more difficult to achieve with prints – and pales his colours to suggest the effect of the intervening atmosphere.

Colour and light

Both works are notable for the brilliance of their colours.

In the Luncheon, Renoir achieves his effect with a surprisingly small number of basic colours – the apricot of the awning and the related red splash on the hat of the seated woman in the left foreground and the related flesh tones; the white of the tablecloth; the dark tints used for some of the clothing; the golden glow of the sunlight; and the pallid green of the foliage.

Firsthand viewers of the Shikian report that the colours are still vivid, though the blue has faded almost entirely from the river [41]. Shumman uses a wide colour range – primarily blues, greens and purples for the clothing and the roofs of the warehouses over the river; a bright yellow for the tatami matting; bright apricot or red splashes in the serving trays, the obi of the geisha in the foreground and the cups, sleeves and hanging lanterns; the blackness of the hairstyles and of the written characters on the lanterns; and the dark green of the foliage and the serving dishes.

In both works, there is a degree of artificiality in the colours used. A major focus of prints such as the Shikian was to highlight a desirable lifestyle, not to reflect reality. Clark comments that print artists never felt obliged to, and never made a pretence of, matching the actual colours of their subject [42]. Similarly, Renoir, who had as a main focus the celebration of physical attractiveness, heightens the colour of cheeks to a rosy hue that is unnatural, even considering the effect of sunlight through the apricot awning.

Although bright, the colours of the Shikian are the flat colours characteristic of woodblock prints. There is a lot of patterning, but little or no gradation or shading of colour [43]. Instead, Shumman uses conventional black lines to define his subjects, to detail their features, and to suggest folds and creases. The woodblock printing process, in which the artist’s design was transferred to carved wooden blocks, was particularly conducive to this more graphical approach [44]. In contrast, Renoir’s painting is almost a study in shadings of colour to create the contours and colours of faces, to suggest depth (for example, the flashes of white on the woman with her hands over her ears); to give a suggestion of beard stubble; the texture of rumpled fabric; the effect of shadow; and the definition of form. By applying colour in small brushstrokes, Renoir has also been able to impart a glowing and jewel-like effect [45].

This difference is highlighted by the ways in which the two artists convey a summery feeling to their works. As the light in Shumman’s work is so even, he is restricted to using circumstantial aspects – the partly outdoor setting, the summer robes of the men, the green foliage of the framing trees, and the number of boats on the river [46]. Renoir uses similar circumstantial devices, but goes further – by using colour to depict the effect of light, he also able to convey the effect of the sun shining on the distant treetops, the golden glow of the sun reflected on clothing and faces (notably on the girl leaning on the railing, the hat of the seated girl at left and the face of the man seated at right) and the brilliant “white” of the tablecloth [47].

In the Luncheon, Renoir achieves his effect with a surprisingly small number of basic colours – the apricot of the awning and the related red splash on the hat of the seated woman in the left foreground and the related flesh tones; the white of the tablecloth; the dark tints used for some of the clothing; the golden glow of the sunlight; and the pallid green of the foliage.

Firsthand viewers of the Shikian report that the colours are still vivid, though the blue has faded almost entirely from the river [41]. Shumman uses a wide colour range – primarily blues, greens and purples for the clothing and the roofs of the warehouses over the river; a bright yellow for the tatami matting; bright apricot or red splashes in the serving trays, the obi of the geisha in the foreground and the cups, sleeves and hanging lanterns; the blackness of the hairstyles and of the written characters on the lanterns; and the dark green of the foliage and the serving dishes.

In both works, there is a degree of artificiality in the colours used. A major focus of prints such as the Shikian was to highlight a desirable lifestyle, not to reflect reality. Clark comments that print artists never felt obliged to, and never made a pretence of, matching the actual colours of their subject [42]. Similarly, Renoir, who had as a main focus the celebration of physical attractiveness, heightens the colour of cheeks to a rosy hue that is unnatural, even considering the effect of sunlight through the apricot awning.

Although bright, the colours of the Shikian are the flat colours characteristic of woodblock prints. There is a lot of patterning, but little or no gradation or shading of colour [43]. Instead, Shumman uses conventional black lines to define his subjects, to detail their features, and to suggest folds and creases. The woodblock printing process, in which the artist’s design was transferred to carved wooden blocks, was particularly conducive to this more graphical approach [44]. In contrast, Renoir’s painting is almost a study in shadings of colour to create the contours and colours of faces, to suggest depth (for example, the flashes of white on the woman with her hands over her ears); to give a suggestion of beard stubble; the texture of rumpled fabric; the effect of shadow; and the definition of form. By applying colour in small brushstrokes, Renoir has also been able to impart a glowing and jewel-like effect [45].

This difference is highlighted by the ways in which the two artists convey a summery feeling to their works. As the light in Shumman’s work is so even, he is restricted to using circumstantial aspects – the partly outdoor setting, the summer robes of the men, the green foliage of the framing trees, and the number of boats on the river [46]. Renoir uses similar circumstantial devices, but goes further – by using colour to depict the effect of light, he also able to convey the effect of the sun shining on the distant treetops, the golden glow of the sun reflected on clothing and faces (notably on the girl leaning on the railing, the hat of the seated girl at left and the face of the man seated at right) and the brilliant “white” of the tablecloth [47].

Artistic climate and style

Both works happen to have been produced during the golden ages of styles that were in the process of shedding themselves of earlier, less prestigious, reputations.

In Japan, there had been a perception among some traditionalists that ukiyo-e woodblock prints were a lesser form of art. This perception was based partly on the limited role of the artist in the creation of the print, the commercial nature of the process, the “vulgar” and often salacious nature of the subject matter, the relatively unsophisticated nature of the market, the sometimes injudicious colouring and even the extreme cheapness of the prints [48].

However, the Shikian was created during the relatively short period after 1780 that is sometimes described as the “golden age” of ukiyo-e prints. In this period, a number of factors came together – the refinement of full colour printing techniques, greater compositional and pictorial sophistication, the impact of great practitioners such as Kiyonaga, Utamaro and Eishi, the emergence of major entrepreneurial publishers such as Tsutaya Juzaburo, a growing and enthusiastic market with more money to spend, and a fairly relaxed official attitude to censorship (at least before the Kansei sumptuary reforms of the late 1780s) [49]. During this period, ukiyo-e prints therefore emerged as a leading art form, and to an extent shook off their earlier reputation as a “second best” to painting [50].

At the time of the Luncheon, France too was in the process of artistic change. The introduction of Impressionism in the 1860s had been met with a storm of criticism. Although the styles of its individual adherents differed, its general emphasis was on natural colour and outdoor light effects, imperfect human perceptions, fleeting impressions, non-traditional contemporary subjects, and the application of paint in individual small touches rather than blended strokes. This initially exposed it to derision as lacking the finish that true “art” should exhibit. By the time of the Luncheon in 1881, however, Impressionism had achieved considerable success in challenging the pre-eminence of the State-organised Salon as the determinant of acceptable style and commercial success. Although its creative force barely survived the end of the century, its continuing audience appeal ensured that it would remain as one of the more popular styles in the history of western art.

Perhaps reflecting the changing fortunes of their respective genres, both artists were also in the process of their own individual transitions. Shumman’s personal style had been particularly influenced by Kiyonaga’s innovations, with an emphasis on relaxed, dignified figures, whose attenuated height stressed the easy splendour of their clothing [51]; open air compositions with a detailed sense of place; and extensive use of compositions across two or three sheets to produce wide, connected views. However, Shumman’s artistic interests went beyond ukiyo-e prints and he designed only a small number of them [52]. Within a short period after the Shikian, he virtually abandoned commercial prints and turned almost exclusively to the new surimono genre of privately commissioned prints for special occasions [53].

For his part, Renoir had always been associated with Impressionism, partnering with Monet at La Grenouillere in the late 1860s to produce pioneering studies of the impact of light on water (fig 5). However, he did not share the disdain of many Impressionists for the Old Masters. By 1883, shortly after the Luncheon, he finally concluded that that Impressionism was a blind alley [54], and moved back to more traditional forms and lines, and towards more timeless subject matter, such as female nudes, sometimes of a monumental size. This seems purely a matter of personal preference, though it was also possibly influenced by a medical crisis and by the fact that his close relationship with his future wife tended to alienate him from his more bohemian friends [55]. With the benefit of hindsight, the Luncheon can be seen as a transitional work in this process. It retains Impressionist elements in the background and in the depiction of light effects on surfaces [56], but the foreground figures have a much more solid, focused and sculpturally rounded feel, as distinct from the rather evanescent, surface appearance on many Impressionist subjects [57].

In Japan, there had been a perception among some traditionalists that ukiyo-e woodblock prints were a lesser form of art. This perception was based partly on the limited role of the artist in the creation of the print, the commercial nature of the process, the “vulgar” and often salacious nature of the subject matter, the relatively unsophisticated nature of the market, the sometimes injudicious colouring and even the extreme cheapness of the prints [48].

However, the Shikian was created during the relatively short period after 1780 that is sometimes described as the “golden age” of ukiyo-e prints. In this period, a number of factors came together – the refinement of full colour printing techniques, greater compositional and pictorial sophistication, the impact of great practitioners such as Kiyonaga, Utamaro and Eishi, the emergence of major entrepreneurial publishers such as Tsutaya Juzaburo, a growing and enthusiastic market with more money to spend, and a fairly relaxed official attitude to censorship (at least before the Kansei sumptuary reforms of the late 1780s) [49]. During this period, ukiyo-e prints therefore emerged as a leading art form, and to an extent shook off their earlier reputation as a “second best” to painting [50].

At the time of the Luncheon, France too was in the process of artistic change. The introduction of Impressionism in the 1860s had been met with a storm of criticism. Although the styles of its individual adherents differed, its general emphasis was on natural colour and outdoor light effects, imperfect human perceptions, fleeting impressions, non-traditional contemporary subjects, and the application of paint in individual small touches rather than blended strokes. This initially exposed it to derision as lacking the finish that true “art” should exhibit. By the time of the Luncheon in 1881, however, Impressionism had achieved considerable success in challenging the pre-eminence of the State-organised Salon as the determinant of acceptable style and commercial success. Although its creative force barely survived the end of the century, its continuing audience appeal ensured that it would remain as one of the more popular styles in the history of western art.

Perhaps reflecting the changing fortunes of their respective genres, both artists were also in the process of their own individual transitions. Shumman’s personal style had been particularly influenced by Kiyonaga’s innovations, with an emphasis on relaxed, dignified figures, whose attenuated height stressed the easy splendour of their clothing [51]; open air compositions with a detailed sense of place; and extensive use of compositions across two or three sheets to produce wide, connected views. However, Shumman’s artistic interests went beyond ukiyo-e prints and he designed only a small number of them [52]. Within a short period after the Shikian, he virtually abandoned commercial prints and turned almost exclusively to the new surimono genre of privately commissioned prints for special occasions [53].

For his part, Renoir had always been associated with Impressionism, partnering with Monet at La Grenouillere in the late 1860s to produce pioneering studies of the impact of light on water (fig 5). However, he did not share the disdain of many Impressionists for the Old Masters. By 1883, shortly after the Luncheon, he finally concluded that that Impressionism was a blind alley [54], and moved back to more traditional forms and lines, and towards more timeless subject matter, such as female nudes, sometimes of a monumental size. This seems purely a matter of personal preference, though it was also possibly influenced by a medical crisis and by the fact that his close relationship with his future wife tended to alienate him from his more bohemian friends [55]. With the benefit of hindsight, the Luncheon can be seen as a transitional work in this process. It retains Impressionist elements in the background and in the depiction of light effects on surfaces [56], but the foreground figures have a much more solid, focused and sculpturally rounded feel, as distinct from the rather evanescent, surface appearance on many Impressionist subjects [57].

Characters, dress and mood

Both works set out to portray attractive subjects. However, these portrayals are radically different, reflecting not only natural physical differences between Japanese and French people, but also differences in cultural and personal concepts of attractiveness.

Beauty and reality

Concepts of beauty change over time, but for a Japanese female beauty of the late eighteenth century, desirable characteristics included a long oval face (the shape of a melon seed [58]), a fair complexion, long legs, slim figure, straight nose and small mouth. A beautiful woman should not be stocky, or have red cheeks [59], or an upturned nose. Japanese artistic conventions, originally influenced by Buddhist ideas of harmony and universality, added some glosses to this. For example, most facial features and contours were typically minimised, with mouths shrinking to tiny buds, and eyes reduced almost to straight lines. Shumman’s women, as may be expected, satisfy all of these descriptions. Renoir’s women, however, present a total contrast. They are typically round faced (not oval), rosy cheeked (not pale), well padded (not slim), and have prominent mouths (not buds). While part of the reason for these differences may lie in artistic tradition or physical racial variations, they are also attributable to Renoir’s own strong personal preferences. According to his son, Renoir liked women who had a tendency to grow fat, with small noses, wide mouths, full lips and blonde hair [60].

Shumman’s adoption of traditional or conventional methods of depiction is probably at the expense of fully expressing the individuality of his subjects. This, however, was not something that particularly mattered to him, or to his audience [61]. Renoir himself also had a limitation in depicting individuality, but this arose from his constant desire to make everything look attractive. “To my mind,” he said, “A picture should be something pleasant, cheerful, and pretty – yes pretty!”[62]. Accordingly, he consistently glamourised or flattered his subjects. All of the characters in his painting were based on real-life people, some of them quite well known [63], but many of these depictions would have been totally unrecognisable even to their friends [64]. A comparison of a photo of the painter Gustave Caillebotte (fig 6)and Renoir’s version of the same man in the left foreground of the painting (fig 7) vividly illustrates the contrast between art and reality.

Shumman’s adoption of traditional or conventional methods of depiction is probably at the expense of fully expressing the individuality of his subjects. This, however, was not something that particularly mattered to him, or to his audience [61]. Renoir himself also had a limitation in depicting individuality, but this arose from his constant desire to make everything look attractive. “To my mind,” he said, “A picture should be something pleasant, cheerful, and pretty – yes pretty!”[62]. Accordingly, he consistently glamourised or flattered his subjects. All of the characters in his painting were based on real-life people, some of them quite well known [63], but many of these depictions would have been totally unrecognisable even to their friends [64]. A comparison of a photo of the painter Gustave Caillebotte (fig 6)and Renoir’s version of the same man in the left foreground of the painting (fig 7) vividly illustrates the contrast between art and reality.

The fact that so many of the models for Renoir’s painting were known raises the issue of whether the Luncheon was intended to be viewed as a depiction of real-life identifiable people, or of an anonymous, generic group. The issue is, however, probably not as relevant as may initially be thought. For one thing, it seems that the models were not in fact as well known as we imagine them now to be. The degree of modern interest in the painting and in identifying the models – recently the subject of a popular novel – has probably exaggerated their fame. Odd as it may seem, they may be better known today then they were in 1881. In fact, it has been suggested that in fact only two of the characters – Charles Ephrussi (top hat) and Jeanne Samury (hands over ears), would have been popularly identifiable at the time, and they are minor parts of the painting [65]. The second reason is that, as we have seen, Renoir idealised most of the subjects so much that they would have been almost unrecognisable anyway.

Women's facial aspects

The aspect of the women’s faces in both works also presents an interesting contrast. Following the normal practice in ukiyo-e prints of avoiding full frontal aspects or profiles [66], almost all of Shumman’s women are shown in half or three quarter frontal aspect [67]. This partial aversion of the face from the viewer’s direct gaze may be interpreted as reflecting appropriate feminine reserve or allure. It also enhances the contour of the nose and de-emphasises the cheekbones, which might otherwise present too flat an appearance, while at the same time allowing full expression to the eyes [68]. In direct contrast, the women’s faces in the Luncheon are all depicted either in virtually full frontal aspect (so as to directly concentrate the viewer’s attention on the individual faces), or in strict profile (so as, for example, to highlight an attractively upturned nose).

Dress and stance

One of the attractions of ukiyo-e prints in the market place was their depiction of the latest fashions. Accordingly, some care was typically taken to ensure that the textiles and patterns of robes were on full view. In some prints, textured paper was actually used to mimic the effect of the pattern. One consequence, exemplified by Shumman’s work, was that women were often depicted standing, so that the full height of their gracefully-hanging dresses were on view, or sitting with their dresses arranged artfully around them.

In Renoir’s painting, the emphasis is rather different. Although Paris was the European fashion capital at the time, Renoir’s women, although smartly dressed, were not intended to be fashion plates. Renoir was more interested in matters such as how the colours of the dresses fitted into his overall design, how a material picked up the light, or how a ruffle might present an interesting textural feature. So it is not surprising that only the busts or upper parts of the women are visible.

Hairstyles and accoutrements also provide an interesting contrast. Shumman’s women all wear their hair off their face, coiled (and presumably oiled) with an elaborate array of oversized pins and combs [69]. Renoir’s women generally have loose, less confined hair, with fringes, and all wear the socially obligatory hats [70].

The treatment of men also differs. Swinton refers to a tendency in some Japanese art to depict men as “pretty boys”, and suggests that the appeal of a strong male in military mode was the exception rather than the rule [71]. In the Shikian, the gender of the man on the left is indicated by his shaved bald patch and small obi, but the second man playing the hand game would commonly be identified as a woman by Europeans, unless his top knot and relatively plain outfit were pointed out. The Luncheon, on the other hand, seems to go out of its way to emphasise gender differences. Two of the men proclaim their gender rather emphatically by stripping off their shirts to reveal their bare arms and boatmen’s singlets [72].

In Renoir’s painting, the emphasis is rather different. Although Paris was the European fashion capital at the time, Renoir’s women, although smartly dressed, were not intended to be fashion plates. Renoir was more interested in matters such as how the colours of the dresses fitted into his overall design, how a material picked up the light, or how a ruffle might present an interesting textural feature. So it is not surprising that only the busts or upper parts of the women are visible.

Hairstyles and accoutrements also provide an interesting contrast. Shumman’s women all wear their hair off their face, coiled (and presumably oiled) with an elaborate array of oversized pins and combs [69]. Renoir’s women generally have loose, less confined hair, with fringes, and all wear the socially obligatory hats [70].

The treatment of men also differs. Swinton refers to a tendency in some Japanese art to depict men as “pretty boys”, and suggests that the appeal of a strong male in military mode was the exception rather than the rule [71]. In the Shikian, the gender of the man on the left is indicated by his shaved bald patch and small obi, but the second man playing the hand game would commonly be identified as a woman by Europeans, unless his top knot and relatively plain outfit were pointed out. The Luncheon, on the other hand, seems to go out of its way to emphasise gender differences. Two of the men proclaim their gender rather emphatically by stripping off their shirts to reveal their bare arms and boatmen’s singlets [72].

Class and status

The appearance of upper class gentility in the Shikian is misleading. Courtesans typically came from poor backgrounds, and had commonly been “sold” as very young girls by their poor families into the indentured life in the pleasure quarters. Their customers were likely to be from merchant families, which, although well-off, were ranked in the lowest level of the Japanese social scale. Their portrayal reflects how the mores of the Floating World differed from that of the “real” world outside. This of course, was part of the attraction of ukiyo-e. The townspeople who purchased these prints saw reflections of their own emerging culture – a highly glamourised, socially mobile version of themselves.

Renoir’s characters illustrate a degree of comfortably middle class aspiration, reflecting the social mores of the time. There are no members of the nobility, nor are there farm workers. Instead there is a mixture of the slightly bohemian and the respectable, indicated by the variations in clothing and hats, with an acceptable frisson of daring in the bare arms of the men.

Renoir’s characters illustrate a degree of comfortably middle class aspiration, reflecting the social mores of the time. There are no members of the nobility, nor are there farm workers. Instead there is a mixture of the slightly bohemian and the respectable, indicated by the variations in clothing and hats, with an acceptable frisson of daring in the bare arms of the men.

Mood

The mood of the Luncheon is generally perceived as joyful, a celebration of a completely harmonious world [73]. However, this view is not unanimous. For example, Giorgio de Chirico described the painting as being “full of melancholy and deep ennui … the boredom of a Sunday afternoon, of a trip to the country, of the minor daily tragedies, is fixed in the gestures and expressions of [Renoir’s] modest characters” [74]. It is true that when each character is looked at individually, only two of the fourteen are positively smiling, with a muted amusement being exhibited by only two others. The expressions of all the others are oddly ambiguous [75]. However, this is a painting in which the overall effect is paramount. What we see is a group of relaxed, attractive people in close physical proximity, on a beautiful day, after what was evidently a good meal, with two of the prominent characters smiling out attractively in the general direction of the viewer. Many viewers would probably interpret this as a happy scene, if only because they were very much like to be part of it.

The Shikian also presents a mood of relaxed, understated intimacy, with elements of playfulness being hinted at – the holding of hands by the couple on the left; the hand game being played by the other couple; the bare feet of the two men and of the woman pouring; the cups, fan and other detritus lying round on the matting. Clark’s assessment of the group as “boisterous” [76] does, however, seem overstated.

The Shikian also presents a mood of relaxed, understated intimacy, with elements of playfulness being hinted at – the holding of hands by the couple on the left; the hand game being played by the other couple; the bare feet of the two men and of the woman pouring; the cups, fan and other detritus lying round on the matting. Clark’s assessment of the group as “boisterous” [76] does, however, seem overstated.

Social idealisation

As we have seen, there is a tendency of both artists to idealise the physical appearance of their subjects, and the colours of their world. Both also idealise the social environment, by ignoring the seamy or unsavoury aspects of the worlds they depict. Both were presenting images of a modern world, but they were remarkably sanitised images.

There are a number of reasons for this, which differ to some extent for each artist. The ukiyo-e print industry was built on creating an impression of a dream world. The promise of a perfect world of sex, beauty, fashion and high living was a potent marketing device. The buying public was not interested in the downside. The miseries of many of the indentured women and girls on which places like Nakasu depended simply did not rate, asthe whole industry bathed in the reflected glamour of its top practitioners [77].

In Renoir’s case, there was a similar avoidance of sordid reality, though this was due to his own personal preferences. He simply liked to paint happy, beautiful things and was not interested in dealing with contemporary social issues, or with depicting misery or dissatisfaction. In Kenneth Clark’s words, Renoir, unlike some of his Impressionist friends, exhibited no “awakened conscience” [78]; his was a completely harmonious world in which pain and self-doubt played no part. Renoir himself put the contrast this way: “When Pissarro painted views of Paris, he always put in a funeral, whereas I would have put in a wedding” [79]. Also for personal reasons, Renoir enjoyed painting modern, up-to-date people in modern, up-to-date settings, but was not interested in the artefacts of modern life. He constantly railed against the signs of modernity – everything from motorcars to slum clearance [80]. These things did not interest him, so his idealised painted world simply ignored them.

An additional factor relates to the partly promotional character of both the Shikian and the Luncheon. Ukiyo-e prints, as widely sold commercial products, played an important role in building the reputations of the actors, courtesans, fashions and establishments that they portrayed. The Shikian, by its very title, has a promotional function, underlined by the prominent display of the characters for shi, ki and an that are boldly emblazoned on the red lanterns hanging from the roofline. Similarly, Renoir’s affection for the Chatou region, and his longstanding personal relationship with the supportive owner of the Maison Fournaise, meant that it was unlikely that he would want to portray it in anything but a positive light [81].

A further factor, probably common to both works, has to do with the male perspective. The world of Nakasu was largely a world in which women were exploited for the benefit of men. As ukiyo-e artists were male, and presumably imbued with traditional attitudes favouring a subservient, compliant role for women, it is not surprising that women’s issues or concerns are not to the fore in these works.

It seems clear that Renoir too had a particularly chauvinist attitude toward women, and toward their depiction in his art. His attitude is eloquently captured by his observation that “When I’ve painted a woman’s behind so that I want to touch it, then it’s finished” [82]. Such an attitude is not conducive to gritty depictions.

There are a number of reasons for this, which differ to some extent for each artist. The ukiyo-e print industry was built on creating an impression of a dream world. The promise of a perfect world of sex, beauty, fashion and high living was a potent marketing device. The buying public was not interested in the downside. The miseries of many of the indentured women and girls on which places like Nakasu depended simply did not rate, asthe whole industry bathed in the reflected glamour of its top practitioners [77].

In Renoir’s case, there was a similar avoidance of sordid reality, though this was due to his own personal preferences. He simply liked to paint happy, beautiful things and was not interested in dealing with contemporary social issues, or with depicting misery or dissatisfaction. In Kenneth Clark’s words, Renoir, unlike some of his Impressionist friends, exhibited no “awakened conscience” [78]; his was a completely harmonious world in which pain and self-doubt played no part. Renoir himself put the contrast this way: “When Pissarro painted views of Paris, he always put in a funeral, whereas I would have put in a wedding” [79]. Also for personal reasons, Renoir enjoyed painting modern, up-to-date people in modern, up-to-date settings, but was not interested in the artefacts of modern life. He constantly railed against the signs of modernity – everything from motorcars to slum clearance [80]. These things did not interest him, so his idealised painted world simply ignored them.

An additional factor relates to the partly promotional character of both the Shikian and the Luncheon. Ukiyo-e prints, as widely sold commercial products, played an important role in building the reputations of the actors, courtesans, fashions and establishments that they portrayed. The Shikian, by its very title, has a promotional function, underlined by the prominent display of the characters for shi, ki and an that are boldly emblazoned on the red lanterns hanging from the roofline. Similarly, Renoir’s affection for the Chatou region, and his longstanding personal relationship with the supportive owner of the Maison Fournaise, meant that it was unlikely that he would want to portray it in anything but a positive light [81].

A further factor, probably common to both works, has to do with the male perspective. The world of Nakasu was largely a world in which women were exploited for the benefit of men. As ukiyo-e artists were male, and presumably imbued with traditional attitudes favouring a subservient, compliant role for women, it is not surprising that women’s issues or concerns are not to the fore in these works.

It seems clear that Renoir too had a particularly chauvinist attitude toward women, and toward their depiction in his art. His attitude is eloquently captured by his observation that “When I’ve painted a woman’s behind so that I want to touch it, then it’s finished” [82]. Such an attitude is not conducive to gritty depictions.

Physical and technical implications

A number of implications flow from the fact that the Shikian was a woodblock print, and the Luncheon was an oil painting.

The woodblock printing process enabled an artist’s work to reach a wide, largely urban audience, but it also imposed significant restrictions on the artist’s role. In making a print, that role was to generally limited to creating a design, and deciding on the colours. The design was then transferred to woodblocks by skilled craftsmen, and printed by other craftsman, and distributed and sold by a publisher, who typically might mastermind and supervise the whole project [83] .In many cases, the artist was given a design brief by the publisher, setting out what sort of design was required [84]. The process was therefore a collaborative effort.

In the Shikian, this is explicitly recognised – the publisher’s name (Shueido) appears together with Shumman’s name and seal on the screen on the extreme right, and on the trunk of the tree on the extreme left [85]. On some others of Shumman’s prints, the name of the block cutter is also included. While this was quite unusual for prints of this period, it indicated that Shumman and the cutter had a shared pride in the level of technical achievement [86].

In many cases, the constraints imposed by “giving the market what it wanted” could restrict the creativity of the artist by requiring a rather conservative, repetitive approach to subject matter, style and composition. However, for a number of reasons, these very factors were also capable of operating in favour of the artist. First, the enforced division of effort in print production meant that the artist was freed up from the time consuming tasks of production and marketing. This enabled some ukiyo-e print artists to concentrate on their design strengths, leading some artists (though not Shumman) to become astonishingly prolific. Second, the fact that success could be measured in commercial terms meant that a design innovation that did happen to succeed commercially could quickly become influential [87]. Third, the mass nature of the non-traditional market, and its considerable growth, meant that successful artists could achieve celebrity status, instead of being simply admired by a small circle of sophisticates.

A painter such as Renoir was, of course, in a rather different situation. The Luncheon was entirely his own work, from conception to execution to sale [88]. This gave him considerable artistic independence. However, as the Luncheon was not commissioned, Renoir bore all of the considerable financial risk. On the other hand, he did not have to satisfy a mass market – a single (preferably wealthy) buyer would do – and if he did succeed, all the rewards, both financial and reputational, flowed to him.

The woodblock printing process enabled an artist’s work to reach a wide, largely urban audience, but it also imposed significant restrictions on the artist’s role. In making a print, that role was to generally limited to creating a design, and deciding on the colours. The design was then transferred to woodblocks by skilled craftsmen, and printed by other craftsman, and distributed and sold by a publisher, who typically might mastermind and supervise the whole project [83] .In many cases, the artist was given a design brief by the publisher, setting out what sort of design was required [84]. The process was therefore a collaborative effort.

In the Shikian, this is explicitly recognised – the publisher’s name (Shueido) appears together with Shumman’s name and seal on the screen on the extreme right, and on the trunk of the tree on the extreme left [85]. On some others of Shumman’s prints, the name of the block cutter is also included. While this was quite unusual for prints of this period, it indicated that Shumman and the cutter had a shared pride in the level of technical achievement [86].

In many cases, the constraints imposed by “giving the market what it wanted” could restrict the creativity of the artist by requiring a rather conservative, repetitive approach to subject matter, style and composition. However, for a number of reasons, these very factors were also capable of operating in favour of the artist. First, the enforced division of effort in print production meant that the artist was freed up from the time consuming tasks of production and marketing. This enabled some ukiyo-e print artists to concentrate on their design strengths, leading some artists (though not Shumman) to become astonishingly prolific. Second, the fact that success could be measured in commercial terms meant that a design innovation that did happen to succeed commercially could quickly become influential [87]. Third, the mass nature of the non-traditional market, and its considerable growth, meant that successful artists could achieve celebrity status, instead of being simply admired by a small circle of sophisticates.

A painter such as Renoir was, of course, in a rather different situation. The Luncheon was entirely his own work, from conception to execution to sale [88]. This gave him considerable artistic independence. However, as the Luncheon was not commissioned, Renoir bore all of the considerable financial risk. On the other hand, he did not have to satisfy a mass market – a single (preferably wealthy) buyer would do – and if he did succeed, all the rewards, both financial and reputational, flowed to him.

Surface and appearance

We have mentioned earlier the propensity of the woodblock printing process to strengthen the prominence and quality of line, and its limitations in displaying the variable effects of light. Additional effects resulted from the medium’s lack of plasticity.

Working in oil paint, Renoir was able to use variations in thickness to suggest differences in the surface texture (impasto). This is particularly evident in the foreground of the painting, where he uses deep applications of layered paint to suggest the texture of the seated woman’s dress, the crumpled table cloth and the glittering wine glasses and bottles. In contrast, the river and landscape in the background are painted lightly, almost as in a wash. This reflects the shimmering effect of sunlight upon water, and also gives depth to the painting by making the background recede into a less distinct distance.

Woodblock printing did not allow for physical variations in the actual surface of the paint or ink itself. However, it could go some way in achieving analogous effects by varying the texture of the paper that was used. Printers could imitate the textures of quilted or brocaded fabrics by embossing the paper with pattern and texture [89], a technique reserved for the more expensive prints. The slightly three-dimensional effect that was produced often tended to become flattened over time.

The medium also had implications for the actual process of creation. A plastic medium such as oil paint can be reworked and even scraped off to correct errors or to implement the artist’s changes of mind [90]. This flexibility did not apply for Shumman. Once the final design was transmitted to the woodblock, the die was cast.

Working in oil paint, Renoir was able to use variations in thickness to suggest differences in the surface texture (impasto). This is particularly evident in the foreground of the painting, where he uses deep applications of layered paint to suggest the texture of the seated woman’s dress, the crumpled table cloth and the glittering wine glasses and bottles. In contrast, the river and landscape in the background are painted lightly, almost as in a wash. This reflects the shimmering effect of sunlight upon water, and also gives depth to the painting by making the background recede into a less distinct distance.

Woodblock printing did not allow for physical variations in the actual surface of the paint or ink itself. However, it could go some way in achieving analogous effects by varying the texture of the paper that was used. Printers could imitate the textures of quilted or brocaded fabrics by embossing the paper with pattern and texture [89], a technique reserved for the more expensive prints. The slightly three-dimensional effect that was produced often tended to become flattened over time.

The medium also had implications for the actual process of creation. A plastic medium such as oil paint can be reworked and even scraped off to correct errors or to implement the artist’s changes of mind [90]. This flexibility did not apply for Shumman. Once the final design was transmitted to the woodblock, the die was cast.

Size

For many who are accustomed to seeing only reproductions of art works, it may come as a surprise that the Luncheon is more than ten times the size of the Shikian.

At 129 x 172 cms, the Luncheon is also much bigger than the average Impressionist painting. The large size may be attributable to Renoir’s desire to make a major statement with this painting, possibly reflecting a tendency in some western art (and western viewers) to associate the size of individual artworks with their importance.

The two panels of the Shikian total just 36 x 50cms. The size of woodblock prints was of course limited by the size of woodblock and paper available, and the Shikian conforms to the “large” (oban) format introduced in 1784 [91].

The relative sizes reflect the different expectations as to how the works would be viewed .The Luncheon was intended to be hung on a wall, and to dominate a room (as it does). Woodblock prints were instead intended for more intimate viewing, and were commonly mounted in albums or pasted to a screen.

At 129 x 172 cms, the Luncheon is also much bigger than the average Impressionist painting. The large size may be attributable to Renoir’s desire to make a major statement with this painting, possibly reflecting a tendency in some western art (and western viewers) to associate the size of individual artworks with their importance.

The two panels of the Shikian total just 36 x 50cms. The size of woodblock prints was of course limited by the size of woodblock and paper available, and the Shikian conforms to the “large” (oban) format introduced in 1784 [91].

The relative sizes reflect the different expectations as to how the works would be viewed .The Luncheon was intended to be hung on a wall, and to dominate a room (as it does). Woodblock prints were instead intended for more intimate viewing, and were commonly mounted in albums or pasted to a screen.

Conclusion

Despite the obvious differences in the eras, cultures and places in which the Shikian and the Luncheon were produced, there are many striking parallels in the two works.

The philosophical “floating world” approach, rather surprisingly, turns out to be rather similar for both works, as does the focus on depicting a slice of modern life. Their real-life physical settings are strikingly similar, as are their compositions. Both works were created during “golden ages” for their genre, and both appeared close to turning points in their creator’s artistic lives. Both works depict the idealised pleasures of an emerging non-traditional urban class, in a genre that challenged traditional artistic approaches.

Countering these similarities, however, are equally marked differences. Some of these have cultural and personal roots, for example the concept of how beauty should be depicted. The physical constraints of the respective media, and the different commercial markets in which the works were sold, result in different approaches to the role of the artist and to the appearance of the work. Artistic differences, such as in the depiction of colour, light and depth, also dramatically affect the “look” of the works.

With this mixture of similarities and differences, the Shikian and the Luncheon provide a fascinating case study on the complex interplay between the factors that combine to create a work of art. □

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2019

How to cite this article

This article may be cited as:

Philip McCouat, "The Floating Worlds of Paris and Edo", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

You may also enjoy….

If you enjoyed this article, you may also be interested in:

On the trail of the Last Supper

The emergence of the winter landscape: Bruegel and his predecessors

Toulouse-Lautrec, the bicycle and the women's movement

Prussian blue and its partner in crime

We welcome your comments on this article

The philosophical “floating world” approach, rather surprisingly, turns out to be rather similar for both works, as does the focus on depicting a slice of modern life. Their real-life physical settings are strikingly similar, as are their compositions. Both works were created during “golden ages” for their genre, and both appeared close to turning points in their creator’s artistic lives. Both works depict the idealised pleasures of an emerging non-traditional urban class, in a genre that challenged traditional artistic approaches.

Countering these similarities, however, are equally marked differences. Some of these have cultural and personal roots, for example the concept of how beauty should be depicted. The physical constraints of the respective media, and the different commercial markets in which the works were sold, result in different approaches to the role of the artist and to the appearance of the work. Artistic differences, such as in the depiction of colour, light and depth, also dramatically affect the “look” of the works.

With this mixture of similarities and differences, the Shikian and the Luncheon provide a fascinating case study on the complex interplay between the factors that combine to create a work of art. □

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2019

How to cite this article

This article may be cited as:

Philip McCouat, "The Floating Worlds of Paris and Edo", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

You may also enjoy….

If you enjoyed this article, you may also be interested in:

On the trail of the Last Supper

The emergence of the winter landscape: Bruegel and his predecessors

Toulouse-Lautrec, the bicycle and the women's movement

Prussian blue and its partner in crime

We welcome your comments on this article

End Notes

1. Currently held at the British Museum, London. The print has been given various titles. For convenience, I will refer to it in this article by the shorthand term, Shikian. It is variously dated as being between 1786 and 1788. The precise date may actually be significant, because it would indicate whether the print was created before or after the 1787 Yoshiwara fire which contributed to the heyday of Nakasu, the setting for the print.

2. 1757-1820. The name is also spelled as Shunman, though this version has been described as an “archaic romanisation”: Richard Lane, “Ukiyo-E Paintings Abroad: A Review Article”, Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 23, No. 1/2 (1968), 190-207.

3. In French, Le Déjeuner des Canotiers. This work, which I shall generally refer to by the shorthand term, Luncheon, is held in The Phillips Collection, Washington.

4. 1841-1919.

5. Donald Jenkins, The Floating World Revisited, Portland Art Museum in association with University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1993, 15.