Comets in Art

By Philip McCouat

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

UPDATE! 15 June 2015: Seven months after finishing its 10 year journey through the solar system, Rosetta’s probe Philae started communicating with Earth. For the latest progress of this incredible project, check out http://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2015/06/14/rosettas-lander-philae-wakes-up-from-hibernation/

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

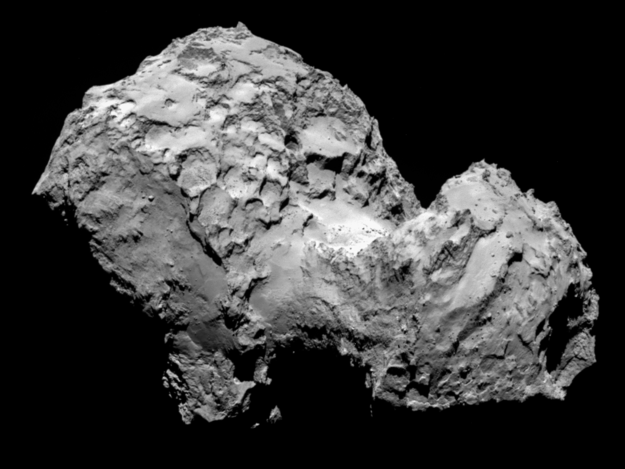

As I write this (August 2014), the European space probe Rosetta, launched more than ten years ago, is finally rendezvousing with Comet 67P / Churyumov-Gerasimenko, some 400 million kilometres away from Earth [1]. Rosetta has travelled over 6 billion kilometres to achieve this remote coupling, somewhere between the orbits of Jupiter and Mars. It needed four flybys of Mars and Earth, using their gravitational forces as a slingshot, for Rosetta to build up the speed needed to catch up with its target. Both the comet and Rosetta are now travelling at 55,000 kilometres an hour, just 100 kilometres apart (Fig 1) [2].

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

UPDATE! 15 June 2015: Seven months after finishing its 10 year journey through the solar system, Rosetta’s probe Philae started communicating with Earth. For the latest progress of this incredible project, check out http://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2015/06/14/rosettas-lander-philae-wakes-up-from-hibernation/

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

As I write this (August 2014), the European space probe Rosetta, launched more than ten years ago, is finally rendezvousing with Comet 67P / Churyumov-Gerasimenko, some 400 million kilometres away from Earth [1]. Rosetta has travelled over 6 billion kilometres to achieve this remote coupling, somewhere between the orbits of Jupiter and Mars. It needed four flybys of Mars and Earth, using their gravitational forces as a slingshot, for Rosetta to build up the speed needed to catch up with its target. Both the comet and Rosetta are now travelling at 55,000 kilometres an hour, just 100 kilometres apart (Fig 1) [2].

Rosetta’s ultimate task is to release its three-legged lander/laboratory Philae onto the actual surface of the comet – the first time this feat has ever been achieved – where it will take samples and use radio waves to probe the comet’s interior [3]. Both Philae and Rosetta will then accompany the comet for about a year, until it reaches its closest approach to the sun (“perihelion”, expected mid-July 2015), and then later as it heads off in the direction of Jupiter. It’s hoped that the information gleaned from the mission will shed light on fundamental questions that have intrigued observers for thousands of years – What are comets made of? Where do they come from? Can they provide clues about how the planets were formed? Could they have contained the ice that became Earth’s original oceans? Might they possibly even contain the ultimate building blocks of life?

It is remarkable that we still know so little about these wanderers of the Solar System. But historically this void in our knowledge has also meant that, since early times, comets have often come to mean what we want them to mean. So, depending on the circumstances, comets have been invested with particular meanings, being represented in common thought and art in a multitude of ways – not just as an object of awe and wonder, but as a presentiment of disaster, a sign of divinity, a reminder about deep time, a warning about the end of the world, and even just as a badge of worldly power or aristocratic prestige. In this article, we’ll be examining these different interpretations, primarily as they have been reflected in, or propagated by, selected artworks of the time [4].

It is remarkable that we still know so little about these wanderers of the Solar System. But historically this void in our knowledge has also meant that, since early times, comets have often come to mean what we want them to mean. So, depending on the circumstances, comets have been invested with particular meanings, being represented in common thought and art in a multitude of ways – not just as an object of awe and wonder, but as a presentiment of disaster, a sign of divinity, a reminder about deep time, a warning about the end of the world, and even just as a badge of worldly power or aristocratic prestige. In this article, we’ll be examining these different interpretations, primarily as they have been reflected in, or propagated by, selected artworks of the time [4].

So what are comets?

We currently know of about 5,000 comets, but the total number is probably in the billions, or even trillions. Comet 67P itself was discovered as recently as 1969. Once believed to be some sort of star – the word comet is derived from the Greek komḗtēs, meaning “long-haired star” – comets came to be envisaged by the mid-20th century as “dirty snowballs” consisting an icy nucleus primarily of frozen volatiles such as water, carbon dioxide, methane and ammonia, together with rock and dust. Today, this perception has been modified somewhat to account for the darker nucleus that some observed comets have exhibited. Comet 67P for example, initially appears to have a predominantly dark, dusty crust and, although being a very cold -70ºC, is apparently not covered in ice [5].

Comets vary widely in size, with 67P being medium-sized at about five kilometres across, just about the size of a city suburb. Generally, they come from the outer regions of the solar system and travel in elongated elliptical orbits around the Sun. The length of those orbits can differ enormously – for example, Halley’s Comet (Fig 2), the most familiar to us, reappears every 76 years, but some can take hundreds or even thousands of years to do so, and some never return at all. The orbital shapes of comets are also variable, with the narrower orbits generating the highest speeds. This overwhelming variability, coupled with the immense times and distances involved, created almost insoluble problems for early observers and contributed to the mysterious and rather fearsome reputation that comets acquired.

The speed of any comet also varies over time, with its maximum being reached at the comet’s closest point to the sun. The characteristic spectacular bright “tails” that we all associate with comets are expected to become visible on 67P about a month before it reaches perihelion. At this stage, the components of the comet will be being released by the sunlight to form a “coma” or halo-like bright hood around the comet’s nucleus [6]. Typically, two “tails” will be visible, both pointing away from the direction of the sun – one of slightly bluish ionised gases, and the other a more yellow tail of dust. However, the number, shape and composition of the tails, like most attributes of comets, are all variable.

The speed of any comet also varies over time, with its maximum being reached at the comet’s closest point to the sun. The characteristic spectacular bright “tails” that we all associate with comets are expected to become visible on 67P about a month before it reaches perihelion. At this stage, the components of the comet will be being released by the sunlight to form a “coma” or halo-like bright hood around the comet’s nucleus [6]. Typically, two “tails” will be visible, both pointing away from the direction of the sun – one of slightly bluish ionised gases, and the other a more yellow tail of dust. However, the number, shape and composition of the tails, like most attributes of comets, are all variable.

Some early representations of comets

Comets seem to have always made a deep impression on humans. Comet-like images have been found in rock art from various ancient cultures, dating back thousands of years. However, the understandably-simplified nature of these images often makes identification a rather ambiguous and subjective affair. One interesting candidate can be found at Valcamonica, an extensive World Heritage-listed rock art site in northern Italy, which stretches back some 8,000 years. (Fig 3) [7].

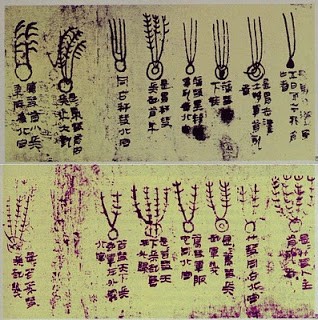

Many definite early images of comets were made by the Chinese, who also documented them thoroughly. A most remarkable example is provided by the ancient Mawangdui Silk Book, which only came to light in the early 1970s. While excavating three sealed tombs dating back to 168 BC, Chinese archaeologists discovered a copy of a book transcribed onto a swathe of silk about 1 ½ metres long. The book, which originally dates back to the 3rd century BC – with the knowledge it contains possibly dating back centuries more – contained 29 drawings and accompanying descriptions that almost certainly qualify as the world’s first detailed writings on comets based on actual observation (Fig 4) [8]. Of the 29 comets recorded, 18 had never been identified before.

Each of the comets appearing in the drawings is identified by name, together with notes or prognostications that were made as to the each comet’s significance. These are mainly negative, with descriptions such as “”General dies”, “rebellion in the State”, “State perishes”, ”Death in the State”, “Death among the Generals”, "Disease in the world” and so on. A few others, however, are two–edged, such as “Internal war; bumper harvest” or ”Army that gains the right direction will win”. One is highly prescriptive – “appearing in Spring, means good harvest, in Summer means drought, in Autumn means flood, in Winter means small battles”[9].

The fact that a comet’s tail points way from the Sun had been discovered by a Chinese astronomer, Li Chun-feng, over 900 years before the same discovery by Europeans [10]. Virtually all of the drawings in the Mawangdui Silk Book conform to this rule. In fact, the degree of detail is extremely advanced, with the various comet shapes being clearly identified. In this respect, the Chinese drawings appear to be more scientifically informative about the real nature of comets than any European illustration until the Renaissance, if not later.

This particular Silk Book was just a small part of the treasures discovered in the tombs. They were also found to contain some of the earliest versions of texts such as the I Ching and other manuscripts comprising some 120,000 words on topics such as military strategy, mathematics, cartography and the classical arts. In addition, befitting the status of the tombs as housing the remains of leaders during the Han Dynasty [11], archaeologists found funeral banners, garments, tapestries, paintings and even the body of a woman known as Lady Dai, still in a remarkable state of preservation after more than 2,000 years (Fig 5). There is an extensive collection of the finds in the Hunan Provincial Museum, a major tourist attraction [12].

The fact that a comet’s tail points way from the Sun had been discovered by a Chinese astronomer, Li Chun-feng, over 900 years before the same discovery by Europeans [10]. Virtually all of the drawings in the Mawangdui Silk Book conform to this rule. In fact, the degree of detail is extremely advanced, with the various comet shapes being clearly identified. In this respect, the Chinese drawings appear to be more scientifically informative about the real nature of comets than any European illustration until the Renaissance, if not later.

This particular Silk Book was just a small part of the treasures discovered in the tombs. They were also found to contain some of the earliest versions of texts such as the I Ching and other manuscripts comprising some 120,000 words on topics such as military strategy, mathematics, cartography and the classical arts. In addition, befitting the status of the tombs as housing the remains of leaders during the Han Dynasty [11], archaeologists found funeral banners, garments, tapestries, paintings and even the body of a woman known as Lady Dai, still in a remarkable state of preservation after more than 2,000 years (Fig 5). There is an extensive collection of the finds in the Hunan Provincial Museum, a major tourist attraction [12].

A portent in the Bayeux Tapestry

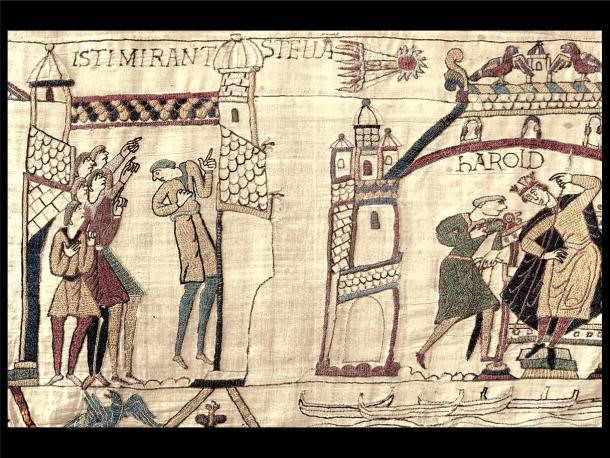

One of the most famous depictions of a historical comet appears on the Bayeux Tapestry [13]. The Tapestry is an impressive 231 feet long but very narrow, thus resembling a frieze. It contains many highly detailed panels, each with its descriptive Latin inscriptions, illustrating the events leading up to the Norman Conquest of England. Its climax is the Battle of Hastings (1066), where William the Conqueror defeated the English King Harold [14].

As it happened, a comet had made a spectacular appearance in 1066, creating quite an impression. The writers of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recounted that, “At that time, throughout all Europe, a portent such as men had never seen before was seen in the heavens. Some declared that the star was a comet, which some call “the long-haired star… It shone every night for a week” [15].

As it happened, a comet had made a spectacular appearance in 1066, creating quite an impression. The writers of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recounted that, “At that time, throughout all Europe, a portent such as men had never seen before was seen in the heavens. Some declared that the star was a comet, which some call “the long-haired star… It shone every night for a week” [15].

This was actually Halley’s Comet, making its regular return after every 76 years. On the tapestry it is shown at a crucial point in the narrative, before the Battle takes place, when Harold has just taken the throne (Fig 6). A group of people on the left are pointing to a strange, flaming broom-like object in the sky, looking in wonder at the “star” [16]. This of course is the comet. On the right, Harold has evidently just been given the news and appears to react with shock. Actually, the comet did not appear until four months after Harold’s coronation, but the Tapestry makers have taken the liberty of bringing it forward, no doubt as a propaganda measure to emphasise the comet’s role as signifying divine judgment on Harold and an evil omen for his (very short) reign.

At the foot of the panel, on the right, are some sketchily-drawn empty boats drifting on the waves, possibly a vision of Harold’s coming defeat, or a reminder of the ill-preparedness of his fleet -- yet more indicators of the certainty of his defeat.

The comet is shown in a flattened, simplified cartoonlike form, but it is surprisingly perceptive in its identification of the essential components of the comet – the nucleus, the coma and the multiple tails.

At the foot of the panel, on the right, are some sketchily-drawn empty boats drifting on the waves, possibly a vision of Harold’s coming defeat, or a reminder of the ill-preparedness of his fleet -- yet more indicators of the certainty of his defeat.

The comet is shown in a flattened, simplified cartoonlike form, but it is surprisingly perceptive in its identification of the essential components of the comet – the nucleus, the coma and the multiple tails.

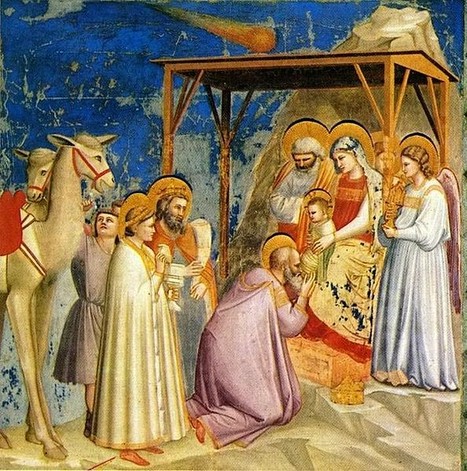

Giotto paints a comet at the Nativity

The early 14th century Florentine artist Giotto [17] was a pioneer in introducing a more naturalistic style in painting, breaking from the far more stylised and formulaic styles of his predecessors. Nowhere is this more evident than in his Adoration of the Magi, part of a famous series painted for the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua in the period 1301-5. In the Adoration, the Bethlehem Star is clearly depicted as a comet. Not only this, the depiction is so realistic and naturalistic that it can legitimately be claimed to be the first realistic Western representation of a comet based on close actual observation.

The idea that the “historical” Bethlehem Star was a comet was actually not new. Origen, a Church Father, had made this suggestion as far back as AD 248, and it coincided with some early pagan beliefs that a comet signified the birth of a king [18]. Padua would also have been a particularly receptive place for an astronomical representation of the Bethlehem Star. As a university town (where Giotto would later teach), it was a centre for mathematical learning and for early astronomy. There is also evidence that Giotto was influenced by the astrologer/philosopher Pietro D’albano [19]. Olson also suggests that Giotto’s pre-existing receptivity to an observation-based art may actually have been increased by the brilliance of the comet’s appearance; if so, it may have actually helped to push Giotto toward an even more radical naturalism “and thus played an important role in determining the future of art”. She also suggests that Giotto was able to paint such a progressive daring image of the comet because of the private status of the Scrovegni chapel [20].

It is generally believed that the particular comet which inspired Giotto’s depiction was Comet Halley, which had made its spectacular re-appearance in 1301, just as Giotto was starting his work in the Scrovegni Chapel [21]. However, David Hughes has argued that it is more likely that Giotto was inspired by a comet that appeared in 1304, rather than Halley’s Comet. He points out that (1) although Giotto’s depiction would seem to be based on actual observation, it is not sufficiently distinctive to be able to say that it is based on Halley in particular; if anything, the very short tail of Giotto’s comet is more reminiscent of the 1304 comet; (2) the 1304 comet was visible for much longer than the 1301 Halley; (3) there was no reason why Giotto, when painting the Star of Bethlehem in 1304 (which is when he started the Adoration), would try to memorise what Halley looked like 2 ½ years previously, when all he had to do was look out the window toward the horizon to see “a beautiful, bright, short-tailed comet for him to paint from life” [22].

The other remarkable aspect of Giotto’s comet – whichever one it was – was that he portrayed it as signalling good news – the birth of a new king to lead the Jews. While previous comets had generally been associated with disasters, pestilence and death, Giotto’s comet is a relatively rare example of a comet that many would have welcomed.

It is generally believed that the particular comet which inspired Giotto’s depiction was Comet Halley, which had made its spectacular re-appearance in 1301, just as Giotto was starting his work in the Scrovegni Chapel [21]. However, David Hughes has argued that it is more likely that Giotto was inspired by a comet that appeared in 1304, rather than Halley’s Comet. He points out that (1) although Giotto’s depiction would seem to be based on actual observation, it is not sufficiently distinctive to be able to say that it is based on Halley in particular; if anything, the very short tail of Giotto’s comet is more reminiscent of the 1304 comet; (2) the 1304 comet was visible for much longer than the 1301 Halley; (3) there was no reason why Giotto, when painting the Star of Bethlehem in 1304 (which is when he started the Adoration), would try to memorise what Halley looked like 2 ½ years previously, when all he had to do was look out the window toward the horizon to see “a beautiful, bright, short-tailed comet for him to paint from life” [22].

The other remarkable aspect of Giotto’s comet – whichever one it was – was that he portrayed it as signalling good news – the birth of a new king to lead the Jews. While previous comets had generally been associated with disasters, pestilence and death, Giotto’s comet is a relatively rare example of a comet that many would have welcomed.

But was the Bethlehem Star Really a comet?

Of course, the fact that Giotto may have been inspired by a comet to portray the Bethlehem Star in this way does not mean that the historical Star, 1300 years before, actually was a comet. But, assuming that the Star was not some type of miracle, what -- if anything at all -- was it? As it happens, it appears that it too, as well as Giotto’s portrayal of it, may have been comet-related.

To explain this, we must first revisit the Biblical account of the incident [23]. According to the source of the original Bethlehem Star story, the Gospel according to St Matthew [24], an unidentified number of “wise men” (also described in other versions of the Bible as “Magi”) came from the east to Jerusalem to worship a child who was “born to be king of the Jews” . They had been attracted there by seeing his “star in the east”. King Herod was troubled by this development. His chief priests and scribes told him that the birth had taken place in Bethlehem, as written by the prophet. So Herod summoned the wise men, asked them when the Star first appeared, and instructed them to go to Bethlehem to “search diligently” for the child, “and when you have found him, bring me word again, that I may come and worship him also”.

The wise men set off, guided by the star which “went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was”. On finding the new-born child there in a house with his mother Mary, the wise men “rejoiced with exceeding great joy”, worshipped him and presented him with gifts. They did not, however, return with this news to Herod. Instead, after being warned by God in a dream, “they departed into their own country another way”. Meanwhile, the child’s father Joseph escaped with Mary and the child to Egypt, as he had been warned by an angel that Herod intended to “seek the young child to destroy him”. The thwarted Herod, furious that he had been “mocked by the wise men”, then “slew all the children that were in Bethlehem, and in all the coasts thereof, from two years old and under…”.

This account, apparently written in about AD 80 to 100, appears to be the only mention of the Star in the New Testament (or, for that matter, of Herod’s so-called massacre of the innocents). But as the story was recounted in subsequent years, it seems that memories of the Star somehow seemed to invest it with an increasingly great size and brightness [25]. Was it in fact based on an actual astronomical event? There appear to be few such events at the time that could have inspired it, other than Halley’s Comet, which appeared in 12 BC, a few years before Jesus’ generally accepted birthdate. If, however, this was the source it would form a remarkable symmetry with Giotto’s depiction in the Adoration also being influenced by the reappearance of the very same comet some 1,300 years later. This would almost be too good to be true.

Another possibility is the comet that appeared over Jerusalem in AD 66. This comet, which also was extremely bright, with an impressive tail, assumed considerable local importance as it was appeared just before a major Jewish uprising, and was taken by some to portend the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70. Jenkins points out that when this comet first appeared, it rose in the eastern sky and travelled west, and that towards the end of its visibility period it appeared to become nearly stationary. These characteristics are compatible with the Star in the East that led the wise men westwards to Bethlehem, and then “stood over” the town. Of course, if the inspiration for Matthew was the AD 66 comet, his account cannot be historically accurate, as this appeared many decades after the Nativity.

Some other possibilities have been suggested, such as rather complex and unusually brilliant conjunctions of planets [26]. As it involves an issue of both fact and faith It is possible that this will never be conclusively settled.

To explain this, we must first revisit the Biblical account of the incident [23]. According to the source of the original Bethlehem Star story, the Gospel according to St Matthew [24], an unidentified number of “wise men” (also described in other versions of the Bible as “Magi”) came from the east to Jerusalem to worship a child who was “born to be king of the Jews” . They had been attracted there by seeing his “star in the east”. King Herod was troubled by this development. His chief priests and scribes told him that the birth had taken place in Bethlehem, as written by the prophet. So Herod summoned the wise men, asked them when the Star first appeared, and instructed them to go to Bethlehem to “search diligently” for the child, “and when you have found him, bring me word again, that I may come and worship him also”.

The wise men set off, guided by the star which “went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was”. On finding the new-born child there in a house with his mother Mary, the wise men “rejoiced with exceeding great joy”, worshipped him and presented him with gifts. They did not, however, return with this news to Herod. Instead, after being warned by God in a dream, “they departed into their own country another way”. Meanwhile, the child’s father Joseph escaped with Mary and the child to Egypt, as he had been warned by an angel that Herod intended to “seek the young child to destroy him”. The thwarted Herod, furious that he had been “mocked by the wise men”, then “slew all the children that were in Bethlehem, and in all the coasts thereof, from two years old and under…”.

This account, apparently written in about AD 80 to 100, appears to be the only mention of the Star in the New Testament (or, for that matter, of Herod’s so-called massacre of the innocents). But as the story was recounted in subsequent years, it seems that memories of the Star somehow seemed to invest it with an increasingly great size and brightness [25]. Was it in fact based on an actual astronomical event? There appear to be few such events at the time that could have inspired it, other than Halley’s Comet, which appeared in 12 BC, a few years before Jesus’ generally accepted birthdate. If, however, this was the source it would form a remarkable symmetry with Giotto’s depiction in the Adoration also being influenced by the reappearance of the very same comet some 1,300 years later. This would almost be too good to be true.

Another possibility is the comet that appeared over Jerusalem in AD 66. This comet, which also was extremely bright, with an impressive tail, assumed considerable local importance as it was appeared just before a major Jewish uprising, and was taken by some to portend the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70. Jenkins points out that when this comet first appeared, it rose in the eastern sky and travelled west, and that towards the end of its visibility period it appeared to become nearly stationary. These characteristics are compatible with the Star in the East that led the wise men westwards to Bethlehem, and then “stood over” the town. Of course, if the inspiration for Matthew was the AD 66 comet, his account cannot be historically accurate, as this appeared many decades after the Nativity.

Some other possibilities have been suggested, such as rather complex and unusually brilliant conjunctions of planets [26]. As it involves an issue of both fact and faith It is possible that this will never be conclusively settled.

The comet that was excommunicated (or not)

In 1456 Diebold Schilling’s Lucerne Chronicle portrayed two comets that appeared in 1456 [27], with a sky raining blood, on a scorched earth with disease, two-headed animals, deformed babies and apparent earthquakes (Fig 8). Such lurid scenes were typically described as God’s comment on the fall of Constantinople and the Ottoman threat to the West -- Mehmed II had recently been besieging Belgrade.

The problem with this was that it was an invention, written in 1513, more than 50 years after the event. Schilling may not have even been born when these claimed disasters occurred. In addition, it seems that “the assertion that the comet was universally considered as a presage of the defeat of the Christians by the Turks, is entirely without foundation. Several contemporary authors even say the very contrary” [28].

To further compound the problem, a legend developed that the comet was so associated with this evil that Pope Callixtus III had excommunicated or “exorcised” it, with the Ave Maria being supplemented by an additional line, “Lord save us from the devil, the Turk, and the comet”. It seem that this too is an invention, repeated as fact by a succession of writers, all relying on secondary sources. These writers included Laplace, Arago and a certain M Babinet, whom we shall meet again in this article (under heading “Daumier and the comet that never came”). In fact, while a Papal Bull certainly was issued against the Turks, soon after the comet had appeared, it seems that no mention at all of the comet has been found in any official documents from the time [29].

However, we should not be too critical. In medieval times, comets were totally inexplicable and unexpected events and would have been terrifying to many people. And, as we shall see, even in the vastly more-educated 20th century, people were not immune to threats that an approaching comet would cause the end of the World [30].

To further compound the problem, a legend developed that the comet was so associated with this evil that Pope Callixtus III had excommunicated or “exorcised” it, with the Ave Maria being supplemented by an additional line, “Lord save us from the devil, the Turk, and the comet”. It seem that this too is an invention, repeated as fact by a succession of writers, all relying on secondary sources. These writers included Laplace, Arago and a certain M Babinet, whom we shall meet again in this article (under heading “Daumier and the comet that never came”). In fact, while a Papal Bull certainly was issued against the Turks, soon after the comet had appeared, it seems that no mention at all of the comet has been found in any official documents from the time [29].

However, we should not be too critical. In medieval times, comets were totally inexplicable and unexpected events and would have been terrifying to many people. And, as we shall see, even in the vastly more-educated 20th century, people were not immune to threats that an approaching comet would cause the end of the World [30].

A badge of power, prestige… or mockery

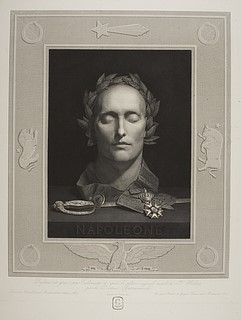

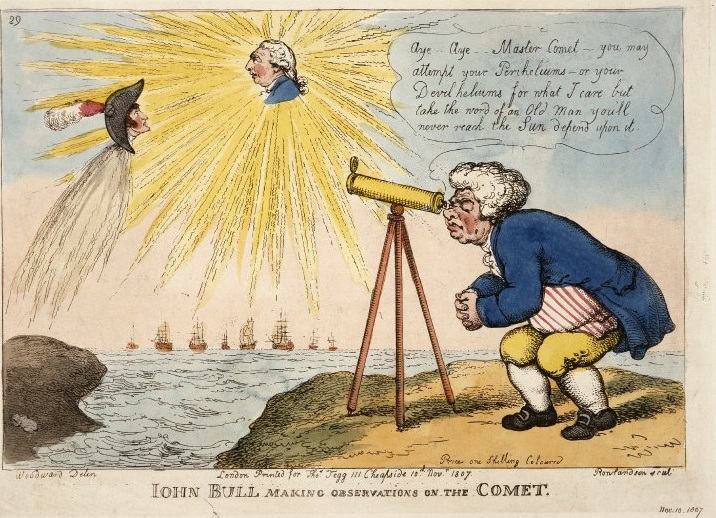

For some people with elevated aspirations about their own worth, comets could sometimes be seen as having a distinctly personal significance. Napoleon Bonaparte, for example adopted various comets as badges of his power and the legitimacy of his reign [31]. The Great Comet of 1769 – the year of his birth – was the first of those specifically linked with him, even being described as Napoleon’s Comet. Depending on which political side you were on, the unusually red colour and spectacular tail of this comet could either be interpreted as a triumphant sign of his glorious reign, or as a reminder of coming bloodshed and destruction. Later, Napoleon would confidently claim that the Great Comet of 1811-12 foretold his certain victory in the Russian Campaign, though this of course did not eventuate. A comet was also supposedly sighted over France one night before his death – though again, this could be variously interpreted as a sad tribute or a joyous celebration.

Napoleon’s linkage of himself to comets was loyally perpetuated in art by painters such as Charles Bouvier and Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, but most specifically in Calamatta’s idealised engraving Still Life with Death Mask of Napoleon, where a stylised comet appears in the top centre surround of the work (Fig 9). Not surprisingly, Napoleon’s enemies played with his claimed cometary connection in far less respectful ways. Thomas Rowlandson’s satiric print shows a comet with Napoleon’s startled face failing to reach the ascendant position of the Sun, represented by the English George III (Fig 10).

Of course. It was not only emperors or kings who could appropriate comets as their personal talismans. In 16th century England, as the power and influence of the British Empire expanded, portraits of upwardly mobile aristocrats became popular. Typically, these paintings were intended as demonstrations of wealth, power and status. Almost certainly, this would have been the intention of young Richard Goodricke, who had his portrait painted in 1578, the year of his marriage [32] by Cornelis Ketel, a highly regarded Dutch portraitist, active in England from 1573 to 1581 [33].

To the usual symbols of rich clothing, a family crest and a haughty aristocratic air (he claimed descent on his mother’s side from Edward I), Goodricke has had the painter add one unexpected touch -- a small glowing comet in the top right of the work, accompanied by a Latin inscription doersum nunquam (“never downwards”). The comet was actually the spectacular Great Comet of 1577, which had appeared for an extended period just the year before. Appropriately enough, the inscription applies equally to the comet and to Goodricke’s confident aspirations as to his own future life and career [34].

Daumier and the comet that never came

The prediction that there would be a re-appearance of a Great Comet in 1857 caused an unusually hysterical wave of panic in Europe, particularly in Paris. The reasons for this were a little obscure. Some time before, certain astronomers had become convinced that the bright comets that had been sighted by previous generations as far back as 1264 and 1556 and were in fact one and the same (the “Charles-Quint” comet), and that this comet would re-appear sometime in the late 1850s. Later, a French journal evidently picked up on an obscure prediction, apparently originally made by the German (or Belgian) Laensberg in his Liege Almanac, In his entry for the week commencing 15 Jun 1857, Laensberg had warned, “about this time, expect a comet”. Through the vagaries of reporting, this eventually came to be understood to be a specific prediction that not only would the comet appear on that date, but that it would also collide with the Earth, and that this would result in the end of the World.

While this prediction was treated with scorn by many, it was also taken very seriously by large parts of the population. It was wryly noted in the press that, as a result of the panic, “Women have miscarried, crops have been neglected, wills have been made, comet-proof suits of clothing have been invented [and] a cometary life insurance company (premiums payable in advance) has been created” [35]. The eminent but mistake-prone physicist/astronomer Jacques Babinet (whom we have already met [36]), tried to quell the panic by declaring – remarkably unconvincingly -- that the impact of the comet would no more affect the stability of the Earth “than a train coming into contact with a fly”.

While this prediction was treated with scorn by many, it was also taken very seriously by large parts of the population. It was wryly noted in the press that, as a result of the panic, “Women have miscarried, crops have been neglected, wills have been made, comet-proof suits of clothing have been invented [and] a cometary life insurance company (premiums payable in advance) has been created” [35]. The eminent but mistake-prone physicist/astronomer Jacques Babinet (whom we have already met [36]), tried to quell the panic by declaring – remarkably unconvincingly -- that the impact of the comet would no more affect the stability of the Earth “than a train coming into contact with a fly”.

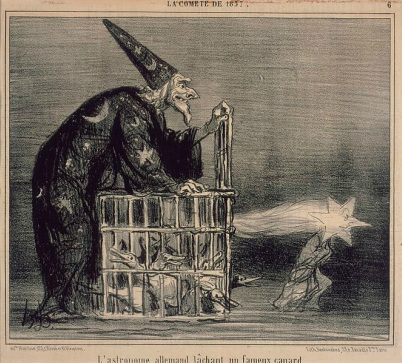

All this was a fertile field for satirists such as the French caricaturist Honoré Daumier. He gently mocked the Parisians’ comet obsession in a series of cartoons published in Le Charivari, and represented the offending German prognosticator as a magician playing a magic trick by releasing a comet-like duck. The joke, of course, was that the French for duck, “canard”, also means “hoax” (Fig 12). As you might expect by now, the much-feared comet did not arrive at all – in Owen Gingerich’s words, it became ”the Great Comet that never came” [37]. But that was not the end of the story.

By coincidence, in the very next year, an extraordinarily bright comet was sighted. Unfortunately for the original predictors, it had nothing to do with the comets of 1264 or 1556 and Daumier was able to return to his theme with a famous cartoon showing the learned Monsieur Babinet intently peering into the heavens with the aid of his telescope, while his lowly housekeeper excitedly taps him on the shoulder (Fig 13). In a triumph of common sense over abstruse learning, she is pointing out the cruelly obvious – the real comet is clearly visible in the opposite direction [38].

Deep time, photography and the meaning of life

The bright comet that caused M Babinet’s embarrassment was in fact Donati’s comet of 1858 [39].This comet became the second most brilliant comet of the 19th century. With its huge scimitar-shaped dust tail – estimated at 50 million miles in length -- and subsidiary plasma tails. It has sometimes been described as the most beautiful comet in history [40]. It was the first to receive massive serious media attention, and became the best recorded of all comets to date.

Donati was visible to the naked eye for an exceptionally long period from August to December and became the first comet to be photographed. George Bond, using a telescope at Harvard College Observatory, was able to capture an image on a collodion-coated glass plate, though it appeared only as “a tiny smudge”, without a tail [41]. At about the same time (perhaps even the night before), an English commercial artist/photographer, William Underwood, evidently obtained a more impressive image, showing “a magnificent tail”, using a portrait camera while standing on Walton Common. Unfortunately, however, this image has not survived [42].

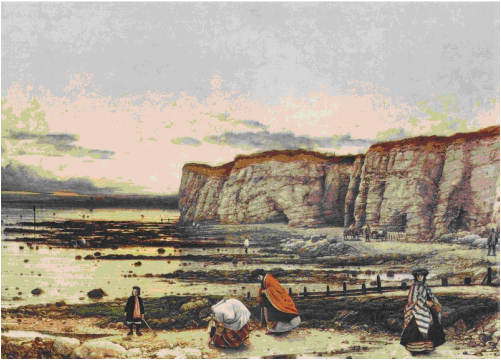

Understandably, Donati’s comet was depicted by many artists, notably William Blake, William Turner (Donati’s Comet, Oxford, 7:30 pm 5 October 1858}, and Samuel Palmer (whose work is discussed further below), but for our purposes one of the most interesting depictions was by William Dyce in his 1860 work Pegwell Bay, Kent: A Recollection of October 5th 1858 (Fig 14). This painting, exhibited the year after the publication of Charles Darwin’s ground-breaking The Origin of Species (1859), came at a time when – for many – scientific enquiry was starting to overtake religious belief as an explanation of the world and humankind’s place in it. In particular, as our article Art in a Speeded up World explains, startling re-evaluations were being made about the age of the universe, the role of evolution and the origins of human existence.

Donati was visible to the naked eye for an exceptionally long period from August to December and became the first comet to be photographed. George Bond, using a telescope at Harvard College Observatory, was able to capture an image on a collodion-coated glass plate, though it appeared only as “a tiny smudge”, without a tail [41]. At about the same time (perhaps even the night before), an English commercial artist/photographer, William Underwood, evidently obtained a more impressive image, showing “a magnificent tail”, using a portrait camera while standing on Walton Common. Unfortunately, however, this image has not survived [42].

Understandably, Donati’s comet was depicted by many artists, notably William Blake, William Turner (Donati’s Comet, Oxford, 7:30 pm 5 October 1858}, and Samuel Palmer (whose work is discussed further below), but for our purposes one of the most interesting depictions was by William Dyce in his 1860 work Pegwell Bay, Kent: A Recollection of October 5th 1858 (Fig 14). This painting, exhibited the year after the publication of Charles Darwin’s ground-breaking The Origin of Species (1859), came at a time when – for many – scientific enquiry was starting to overtake religious belief as an explanation of the world and humankind’s place in it. In particular, as our article Art in a Speeded up World explains, startling re-evaluations were being made about the age of the universe, the role of evolution and the origins of human existence.

Dyce’s painting can therefore be seen as portraying the new awareness of cosmic time in human life. The time-specificity of its title – very close to the comet’s perihelion – and the immediacy of the poses of the woman at right and child at left, suggest the painting’s sense of immediate present. The faint appearance of the almost invisible comet in the sky is a reminder of the almost unimaginable concepts of time and distance that had recently been claimed by astronomers. And the new “geological” time is suggested by the women collecting shells or fossils, and by the eroded chalk cliffs. At the same time, it has been speculated that the rather mournful colours of the painting reflect the nostalgia of the artist – who was also a minister of religion – for the old certainties. In this respect, the location of the painting is significant. Pegwell Bay was the supposed site of the first Christian missionary St Augustine’s arrival in Britain, but it was also a centre famous for its prehistoric fossils [43].

In contrast, Samuel Palmer’s The comet of 1858 as seen from the heights of Dartmoor (Fig 15) appears to be painted simply out of admiration for its natural wonder, the artist’s preoccupation with light, and as a “manifestation of divine presence in the world” [44]. This painting was unfortunately stolen from a private collection in January 2014.

In contrast, Samuel Palmer’s The comet of 1858 as seen from the heights of Dartmoor (Fig 15) appears to be painted simply out of admiration for its natural wonder, the artist’s preoccupation with light, and as a “manifestation of divine presence in the world” [44]. This painting was unfortunately stolen from a private collection in January 2014.

Quite strikingly, the paintings by Turner, Dyce and Palmer can be traced to the same specific date (5 October 1858), close to the comet’s perihelion, either specifically by their title (in the case of Turner and Dyce) or inferentially by their astronomical precision (in the case of Palmer).

Across the world in Japan, where comets were known as hōkiboshi (“broom stars”), the 1858 comet excited contrasting reactions. It so happened that In the period preceding the comet’s appearance, Japan had endured a seemingly endless string of shattering events – political upheavals, prominent deaths, a cholera epidemic, a devastating fire in Kyoto, floods, race riots, crop failures and rapid price inflation. Had the comet shown up at a different time, its transit may have even gone semi-unnoticed. As it was, however, it became something of a lightning rod for differing opinions, permeating political, religious, social and economic debates. To some it was just a comet, to others a portent. And, as often seems to happen, there was sharp disagreement over just what it was a portent of – was it a sad confirmation that the world of the Tokugawa era was falling apart, or was it a beacon of positive and welcome change? [45].

Across the world in Japan, where comets were known as hōkiboshi (“broom stars”), the 1858 comet excited contrasting reactions. It so happened that In the period preceding the comet’s appearance, Japan had endured a seemingly endless string of shattering events – political upheavals, prominent deaths, a cholera epidemic, a devastating fire in Kyoto, floods, race riots, crop failures and rapid price inflation. Had the comet shown up at a different time, its transit may have even gone semi-unnoticed. As it was, however, it became something of a lightning rod for differing opinions, permeating political, religious, social and economic debates. To some it was just a comet, to others a portent. And, as often seems to happen, there was sharp disagreement over just what it was a portent of – was it a sad confirmation that the world of the Tokugawa era was falling apart, or was it a beacon of positive and welcome change? [45].

Cyanide panic and the comet of 1910

Halley’s Comet returned, as expected in 1910, but the general hope of a spectacular show was dampened by an announcement by Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory that the tail of the comet contained cyanogen, a compound of toxic cyanide. As the Earth was expected to pass through this tail, there were understandable, but unfounded, fears among many that the cyanogen “would impregnate the atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet”, as reportedly predicted by the French astronomer Flammarion [46].

There were some who took this extremist prediction seriously – despite the fact that it flew in the face of most scientific opinion – and they reacted in some extreme ways. Some simply panicked, some feverishly took extensive measures to stockpile provisions, or to block off chimneys, windows and doors of their homes to insulate themselves from contamination. Some passively awaited their doom, while others fasted and prayed, partied and prepared for last wild acts of debauchery, or even suicided.

There were some who took this extremist prediction seriously – despite the fact that it flew in the face of most scientific opinion – and they reacted in some extreme ways. Some simply panicked, some feverishly took extensive measures to stockpile provisions, or to block off chimneys, windows and doors of their homes to insulate themselves from contamination. Some passively awaited their doom, while others fasted and prayed, partied and prepared for last wild acts of debauchery, or even suicided.

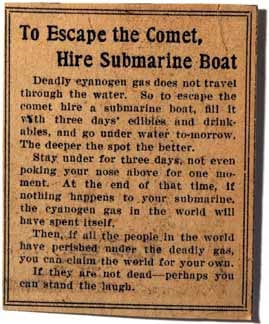

Fig 16: Surviving the comet Fig 16: Surviving the comet

|

Churches held all-night vigils. Charlatans sold “comet pills”, oxygen bottles and gas masks to the gullible or ultracautious [47]. Some newspapers also offered tongue-in-cheek hints for survival, such as hiding down in a submarine while the comet passed over [48].

On 20 May, the dreaded conjunction of the comet’s tail and Earth finally occurred, and … nothing happened. The people who had been fearful emerged sheepishly from their hiding places, while those who had been more sceptical crowed “I told you so”. Once again, doomsday had been averted. Or had it merely been postponed? |

Conclusion

The fact that comets are mysterious, spectacular and relatively rare makes it almost inevitable that people down the ages would attribute considerable significance to them, and that this significance would normally be negative. People tend to be afraid of the unknown, and to find irrational explanations for things that they don’t understand. So we should not be surprised that comets have been blamed for everything from pestilence and famine to wars and death. At the same time, some comets have been chosen as auspicious, as harbingers of good news. In this article, for example, we have seen them positively portrayed as symbols of divine guidance (Giotto), power and legitimacy (the Bayeux Tapestry, Napoleon’s Comet) and prestige (Goodricke). Some artists have used them as reflections on scientific or intellectual advances (Dyce’s Pegwell Bay) and still others have used them to satiric effect (Daumier, Rowlandson).

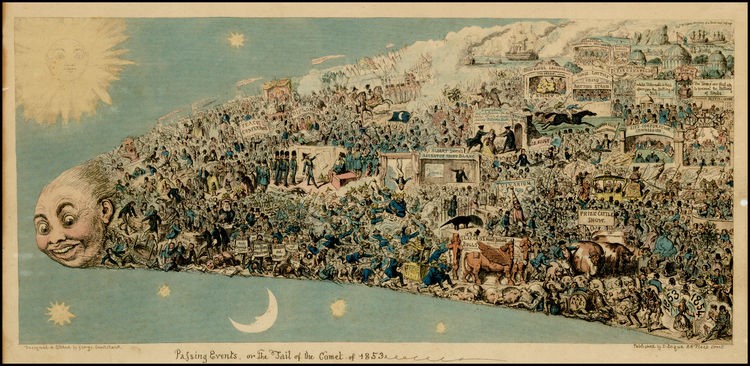

This article has necessarily been very selective. Without extending it to an inconvenient length, it has not been possible to touch on the depictions of comets by many artists from Durer to Kandinsky. Nor have we dealt with comets which are not necessarily art-related but which have been crucial in making scientific advances – including the 1577 comet on which Tycho Brahe based his conclusion that comets travelled outside the moon, the 1680 comet which Newtown used in developing his theory of gravitation and the 1682 comet which was crucial to Edmond Halley in making his famous prediction of its eventual return. These are stories that remain to be told. But, in conclusion, can I offer you George Cruikshank's brilliant representation of the Comet of 1853, with the comet's impossibly crowded tail acting as a review of that year's events.

This article has necessarily been very selective. Without extending it to an inconvenient length, it has not been possible to touch on the depictions of comets by many artists from Durer to Kandinsky. Nor have we dealt with comets which are not necessarily art-related but which have been crucial in making scientific advances – including the 1577 comet on which Tycho Brahe based his conclusion that comets travelled outside the moon, the 1680 comet which Newtown used in developing his theory of gravitation and the 1682 comet which was crucial to Edmond Halley in making his famous prediction of its eventual return. These are stories that remain to be told. But, in conclusion, can I offer you George Cruikshank's brilliant representation of the Comet of 1853, with the comet's impossibly crowded tail acting as a review of that year's events.

© Philip McCouat 2014, 2015, 2016

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Comets in Art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Comets in Art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

End Notes

1. The letter “P” stands for “periodic”, meaning a comet that reappears. Non-periodic comets are those that will not return for thousands of years, if ever.

2. For updates on Rosetta’s progress, and much useful information on the probe, see the Rosetta website of the European Space Agency (ESA) at http://sci.esa.int/rosetta.

3. Philae is the name of the Nile island on which a dual-language inscribed obelisk was found. The obelisk was used, in conjunction with the Rosetta Stone, in the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphics.

4. For a comprehensive history of comets in art, see Roberta J M Olson, Fire and Ice: A History of Comets in Art, Walker and Co, New York, 1985. This book, though published back in 1985, has been invaluable in the preparation of parts of this article.

5. See http://sci.esa.int/rosetta/54198-harbingers-of-doom-windy-exhalations-or-icy-wanderers/

6. The nucleus and the coma together are called the “head” of the comet.

7. For details of this site, see http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/94.

8. See generally Xi Ze-song, “The Commentary Atlas in the Silk Book of the Han Tomb at Mawangdui”, Chinese Astronomy and Astrophysics, Vol 8, Iss 1 (1984) 1-7; and https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/deepimpact/science/comets-cultures.cfm. Apart from comet images, there other detailed drawings of clouds, mirages, halos, rainbows, lunar occultations and star groups, constituting 250 drawings in total.

9. Xi, op cit at 4-5.

10. Xi, op cit at 5. The European discovery was made in 1531.

11. This covers the 400 years from 206 BC onwards.

12. This museum is evidently closed until 2015, due to refurbishments.

13. Although called a “tapestry”, it is actually embroidered linen. It is displayed in a museum in Bayeux, Normandy.

14. See generally Olson, op cit at 13-15; Mogens Rud, The Bayeux Tapestry and the Battle of Hastings 1066, Christian Eilers, Copenhagen, 1988, 58-9.

15. G N Garmonsway (transl), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, London 1966.

16. The Latin inscription reads ISTI MIRANT STELLA.

17. His full name was Giotto di Bondone.

18. Olson, op cit at 17; R M Jenkins, “The star of Bethlehem and the comet of AD 66”, Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 114, 6, 2004; H Chadwick (tr) Origen: Contra Celsum, CUP, 1953.

19. Roberta J M Olson and Jay M Passachoff, “New information on comet P/Halley as depicted by Giotto di Bondone and other Western artists”, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 187 (1987) 1-11, at 9. Indeed, it has even been has suggested that this influence, rather than the actual apparition of a comet, accounts for the appearance of a comet in Giotto’s work.

20. Olson and Passachoff, op cit at 1, 8-9.

21. Olson, op cit at 17; Olson and Passachoff, op cit.

22. David W Hughes et al, “Giotto’s Comet – was it the Comet of 1304 and not Comet Halley?” Q.J.R. astr Soc (1993) 34, 21. In the end, which particular comet it was is probably not a crucial issue.

23. See the useful discussion in Jenkins, op cit.

24. King James version.

25. Jenkins, op cit at 13.

26. See discussion in E.L. Martin, The Star that Astonished the World, ASK Publications 1991; David W Hughes, The Star of Bethlehem Mystery, Dent, 1979.

27. One of them was presumably Halley. It is also possible that the two comets were one and the same, but depicted before and after perihelion

28. Fr J Stein, “Calixte III et la comète de Halley”, Specola Astronomica Vaticana, II (1909), quoted in William F Rigge, “An Historical Examination of the Connection of Callixtus III with Halley's Comet”, Popular Astronomy, 1910, at 214 - 219.

29. Stein, op cit and Rigge, op cit.

30. See under heading “Cyanide panic and the comet of 1910”.

31. Olson, op cit at 74.

32. Goodricke’s birth year is variously given as 1550 and 1560.

33. It was typical for such portraits to be done by European, not British, artists.

34. As it happened, these do not appear to have been realised, as he died relatively young.

35. Paris correspondent for Harpers Weekly, cited in Owen Gingerich, “The Great Comet that never came”. In The Great Copernicus Chase and other adventures in astronomical history, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992, at 167. This passage was contained in an article widely syndicated round the world.

36. Under the heading “The comet that was excommunicated (or not)”

37. Gingerich, op cit at 165. Though various other unrelated comets did arrive during that year.

38. Olson’s discussion of this incident in Fire and Ice (op cit) at 92-3 appears to overlook the fact that the promised Great Comet of 1877 in fact never arrived.

39. Officially known as C/1858 L1, first observed by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Battista Donati on 2 June 1858.

40. Olson, op cit at 93, though how one could judge comets hundreds of years apart is highly problematical.

41. J M Passachoff, Roberta J M Olson, & Martha L Hazen, “The Earliest Comet Photographs: Usherwood, Bond, and Donati 1858”, Journal for the History of Astronomy, 1996, vol 27, 129, at 131.

42. The oldest surviving photographic plate or print that clearly shows a comet’s tail is therefore, apparently, David Gill’s magnificent photograph of the 1882 comet: Passachoff, op cit at 140.

43. Marcia Pointon, "The Representation of Time in Painting: A Study of William Dyce's Pegwell Bay: A Recollection of October 5th, 1858", Art History, I, March 1978, at 99-103.

44. Rachel Campbell-Johnston, Mysterious Wisdom: The Life and Work of Samuel Palmer, A&C Black, 2011 at 129: Roberta J M Olson, “A water-colour by Samuel Palmer of Donati’s comet, The Burlington Magazine, Vol 132, No 1052 (Nov 1990) 795-6.

45. Laura Nenzi, “Caught in the spotlight: the 1858 comet and late Tokugawa Japan”, Japan Forum, 23(1) 2011: 1-23.

46. “Comet’s Poisonous Tail”, The New York Times, 7 February 1910.

47. Adrian Galea, “Comet Haley in 1910, as viewed from a Maltese perspective”, Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 12(2) 2009 p 167; P Lancaster-Brown, Halley and his Comet, Poole, Blandford Press, 1985.

48. See http://wordcraft.net/comets3.html.

© Philip McCouat 2014, 2015, 2016

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Comets in Art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

2. For updates on Rosetta’s progress, and much useful information on the probe, see the Rosetta website of the European Space Agency (ESA) at http://sci.esa.int/rosetta.

3. Philae is the name of the Nile island on which a dual-language inscribed obelisk was found. The obelisk was used, in conjunction with the Rosetta Stone, in the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphics.

4. For a comprehensive history of comets in art, see Roberta J M Olson, Fire and Ice: A History of Comets in Art, Walker and Co, New York, 1985. This book, though published back in 1985, has been invaluable in the preparation of parts of this article.

5. See http://sci.esa.int/rosetta/54198-harbingers-of-doom-windy-exhalations-or-icy-wanderers/

6. The nucleus and the coma together are called the “head” of the comet.

7. For details of this site, see http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/94.

8. See generally Xi Ze-song, “The Commentary Atlas in the Silk Book of the Han Tomb at Mawangdui”, Chinese Astronomy and Astrophysics, Vol 8, Iss 1 (1984) 1-7; and https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/deepimpact/science/comets-cultures.cfm. Apart from comet images, there other detailed drawings of clouds, mirages, halos, rainbows, lunar occultations and star groups, constituting 250 drawings in total.

9. Xi, op cit at 4-5.

10. Xi, op cit at 5. The European discovery was made in 1531.

11. This covers the 400 years from 206 BC onwards.

12. This museum is evidently closed until 2015, due to refurbishments.

13. Although called a “tapestry”, it is actually embroidered linen. It is displayed in a museum in Bayeux, Normandy.

14. See generally Olson, op cit at 13-15; Mogens Rud, The Bayeux Tapestry and the Battle of Hastings 1066, Christian Eilers, Copenhagen, 1988, 58-9.

15. G N Garmonsway (transl), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, London 1966.

16. The Latin inscription reads ISTI MIRANT STELLA.

17. His full name was Giotto di Bondone.

18. Olson, op cit at 17; R M Jenkins, “The star of Bethlehem and the comet of AD 66”, Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 114, 6, 2004; H Chadwick (tr) Origen: Contra Celsum, CUP, 1953.

19. Roberta J M Olson and Jay M Passachoff, “New information on comet P/Halley as depicted by Giotto di Bondone and other Western artists”, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 187 (1987) 1-11, at 9. Indeed, it has even been has suggested that this influence, rather than the actual apparition of a comet, accounts for the appearance of a comet in Giotto’s work.

20. Olson and Passachoff, op cit at 1, 8-9.

21. Olson, op cit at 17; Olson and Passachoff, op cit.

22. David W Hughes et al, “Giotto’s Comet – was it the Comet of 1304 and not Comet Halley?” Q.J.R. astr Soc (1993) 34, 21. In the end, which particular comet it was is probably not a crucial issue.

23. See the useful discussion in Jenkins, op cit.

24. King James version.

25. Jenkins, op cit at 13.

26. See discussion in E.L. Martin, The Star that Astonished the World, ASK Publications 1991; David W Hughes, The Star of Bethlehem Mystery, Dent, 1979.

27. One of them was presumably Halley. It is also possible that the two comets were one and the same, but depicted before and after perihelion

28. Fr J Stein, “Calixte III et la comète de Halley”, Specola Astronomica Vaticana, II (1909), quoted in William F Rigge, “An Historical Examination of the Connection of Callixtus III with Halley's Comet”, Popular Astronomy, 1910, at 214 - 219.

29. Stein, op cit and Rigge, op cit.

30. See under heading “Cyanide panic and the comet of 1910”.

31. Olson, op cit at 74.

32. Goodricke’s birth year is variously given as 1550 and 1560.

33. It was typical for such portraits to be done by European, not British, artists.

34. As it happened, these do not appear to have been realised, as he died relatively young.

35. Paris correspondent for Harpers Weekly, cited in Owen Gingerich, “The Great Comet that never came”. In The Great Copernicus Chase and other adventures in astronomical history, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992, at 167. This passage was contained in an article widely syndicated round the world.

36. Under the heading “The comet that was excommunicated (or not)”

37. Gingerich, op cit at 165. Though various other unrelated comets did arrive during that year.

38. Olson’s discussion of this incident in Fire and Ice (op cit) at 92-3 appears to overlook the fact that the promised Great Comet of 1877 in fact never arrived.

39. Officially known as C/1858 L1, first observed by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Battista Donati on 2 June 1858.

40. Olson, op cit at 93, though how one could judge comets hundreds of years apart is highly problematical.

41. J M Passachoff, Roberta J M Olson, & Martha L Hazen, “The Earliest Comet Photographs: Usherwood, Bond, and Donati 1858”, Journal for the History of Astronomy, 1996, vol 27, 129, at 131.

42. The oldest surviving photographic plate or print that clearly shows a comet’s tail is therefore, apparently, David Gill’s magnificent photograph of the 1882 comet: Passachoff, op cit at 140.

43. Marcia Pointon, "The Representation of Time in Painting: A Study of William Dyce's Pegwell Bay: A Recollection of October 5th, 1858", Art History, I, March 1978, at 99-103.

44. Rachel Campbell-Johnston, Mysterious Wisdom: The Life and Work of Samuel Palmer, A&C Black, 2011 at 129: Roberta J M Olson, “A water-colour by Samuel Palmer of Donati’s comet, The Burlington Magazine, Vol 132, No 1052 (Nov 1990) 795-6.

45. Laura Nenzi, “Caught in the spotlight: the 1858 comet and late Tokugawa Japan”, Japan Forum, 23(1) 2011: 1-23.

46. “Comet’s Poisonous Tail”, The New York Times, 7 February 1910.

47. Adrian Galea, “Comet Haley in 1910, as viewed from a Maltese perspective”, Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 12(2) 2009 p 167; P Lancaster-Brown, Halley and his Comet, Poole, Blandford Press, 1985.

48. See http://wordcraft.net/comets3.html.

© Philip McCouat 2014, 2015, 2016

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Comets in Art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME