Strange encounters: the collector, the artist and the philosopher

The oddly-productive relationships between the eccentric art collector Albert Barnes, the painter Henri Matisse and the philosopher Bertrand Russell

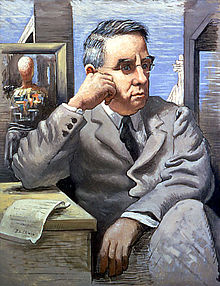

Dr Albert C Barnes, one of the greatest art collectors of the 20th century, was not a man to run away from a fight. On his death, he was described as the American art world’s “most bizarre and colourful personality”, as a man with a “talent for invective” who placed a “paralysing terror” on “the entire American art world of his generation”, and who left behind him “more ill-will than any other single figure in American art”[1].

In this article, we’ll be examining this almost mythical character’s extraordinary relationships with two other major cultural figures – Henri Matisse and Bertrand Russell. Both of these relationships would end unhappily, but would ultimately have far-reaching and beneficial effects on the particpants' future lives and careers.

The extraordinary Dr Barnes

Albert Barnes was born in a working class suburb of Philadelphia in 1872 and, despite a difficult childhood, soon demonstrated intellectual promise and an interest in art, as well as a streak of determination and a well-developed willingness to defend himself [2]. With the help of part-time jobs, he worked his way though medical school, eventually specialising in chemistry. Later, together with a talented German chemist, Herman Hille, who provided most of the scientific expertise, he developed an innovative silver nitrate solution designed to treat blindness in newborn babies of mothers with sexually transmitted disease. The new invention, which they called Argyrol, was cheap and easy to produce, and undeniably effective. Helped by an aggressive marketing campaign, it proved to be an amazing success and the money simply poured in. Within three years, both men were extremely wealthy. Shortly after, however, they fell out, and after a court case, Barnes bought out Hille’s interest, becoming the sole owner.

From about 1912, Barnes used his immense new wealth in collecting art works, showing remarkable prescience and taste – his first Picasso is said to have cost him only a pittance. He later said that the pursuit of art affected him like rabies [3]. It was an obsession that he was eager to indulge.

From about 1912, Barnes used his immense new wealth in collecting art works, showing remarkable prescience and taste – his first Picasso is said to have cost him only a pittance. He later said that the pursuit of art affected him like rabies [3]. It was an obsession that he was eager to indulge.

|

Even the Wall Street Crash of 1929 -- which would prove to be so catastrophic to many businesses -- did nothing to reduce Barnes’ collecting. In fact, it worked to his advantage.

Providentially, Barnes had sold the rights to Argyrol just a couple of months before, at the peak of the market. He was therefore in the fortunate position of being cashed-up in a buyers’ market. The steep fall in art prices meant that he was able to buy art cheaply from other, financially distressed, collectors who desperately needed to liquidate their assets. |

The timing of his sale of the Argyrol rights was also remarkably providential in another way, as it came shortly before the invention of antibiotics, which ultimately wiped out a large part of Argyrol’s market. Barnes’ art collection just grew and grew.

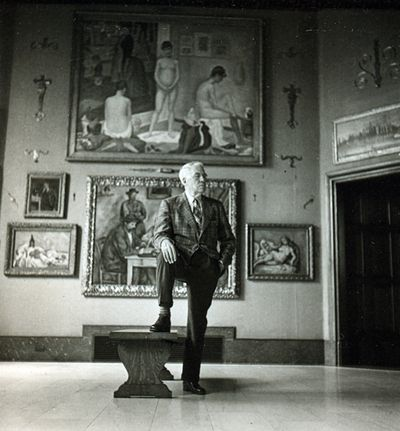

By 1930, the collection included 180 works by Renoir, 69 by Cezanne, and dozens by Matisse – the largest private Matisse collection in the world. The collection was administered under the auspices of the Barnes Foundation, a body controlled (naturally) by Barnes himself, which had as its objective the promotion of “the advancement of education and the appreciation of the fine arts”[4]. Both the collection and the Foundation’s educational classes were housed in a limestone building constructed in the 1920s on a 12 acre estate in Merion, a suburb of Philadelphia.

Art works at Merion were displayed in a typically unusual fashion. Rooms might be dedicated to works of a certain colour, or on a certain theme. Works were not identified, except by name of artist. Old masters were placed next to moderns. A wide variety of art objects, not just paintings, were displayed – one wall, for example, could include works as diverse as Modigliani paintings, Picasso heads, tribal sculptures, European religious carvings and hand forged metal door handles.

Barnes had a tendency to resent people who disagreed with him, offended him or criticised his collection, particularly those in positions of power or those who regarded themselves as born to rule. Over time, his growing list of enemies included journalists, art critics, dealers, other collectors, other millionaires, conservative academics and museum officials [5]. The directness of his attacks on his opponents was notorious. He once described certain members of a respected institutional art collection (which he called “the morgue”) as fiddling, senile, befuddled "director-Neros" who were “habitually in a state of profound alcoholic intoxication”. A university president was described as a “mental delinquent….dumb bunny, false alarm, phony”[6]. In return, Barnes himself was regarded by his enemies as one of the more offensive men in public life. One museum director, after losing a bidding war with Barnes, concluded that “there is no use entering into a pissing contest with a skunk”[7].

Barnes’ idiosyncratic views were also reflected in his response to those who sought permission to view the collection. Officially, access was limited to students at the Foundation, but Barnes exercised his discretion – in a characteristically eccentric way – to admit others. So, for example, he would welcome visitors like Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann or the actor Charles Laughton, but would refuse admission to other notables on the deliberately facetious basis that he was too busy trying to “break the world’s record for goldfish-swallowing”[8], or that he was “out on the lawn singing to the birds” [9]. One rejected journalist was accused of being “either a colossal ignoramus or a demonstrable liar”. TS Eliot received the one-word rejection, “Nuts”; Le Corbusier fared even worse, with “Merde”[10]. Sometimes Barnes signed rejections in the name of his fictional secretary, or even his dog Fidèle-de-Port-Manech who, Barnes claimed, could understand only French [11].

Because of these aberrations, it is all too easy to be critical of Barnes. As a necessary balancing of the ledger, it should be pointed out that in addition to his phenomenal self-made business success, he was an early and active supporter of disadvantaged groups, including Afro-Americans, provided generous employee conditions and benefits for his workforce (which he ensured were mixed-sex and racially integrated), and had a great and genuine commitment to worker education. Barnes was fluent in French, a skilful, even fascinating, lecturer, and displayed impeccable taste and judgment in his collecting [12]. He also studied and wrote widely on art [13]. As Howard Greenfeld points out in The Devil and Dr Barnes, “If Barnes had peacefully collected his paintings, written his books, and directed the educational work of the Foundation, he would have been unqualifiedly respected and universally mourned”[14].

By 1930, the collection included 180 works by Renoir, 69 by Cezanne, and dozens by Matisse – the largest private Matisse collection in the world. The collection was administered under the auspices of the Barnes Foundation, a body controlled (naturally) by Barnes himself, which had as its objective the promotion of “the advancement of education and the appreciation of the fine arts”[4]. Both the collection and the Foundation’s educational classes were housed in a limestone building constructed in the 1920s on a 12 acre estate in Merion, a suburb of Philadelphia.

Art works at Merion were displayed in a typically unusual fashion. Rooms might be dedicated to works of a certain colour, or on a certain theme. Works were not identified, except by name of artist. Old masters were placed next to moderns. A wide variety of art objects, not just paintings, were displayed – one wall, for example, could include works as diverse as Modigliani paintings, Picasso heads, tribal sculptures, European religious carvings and hand forged metal door handles.

Barnes had a tendency to resent people who disagreed with him, offended him or criticised his collection, particularly those in positions of power or those who regarded themselves as born to rule. Over time, his growing list of enemies included journalists, art critics, dealers, other collectors, other millionaires, conservative academics and museum officials [5]. The directness of his attacks on his opponents was notorious. He once described certain members of a respected institutional art collection (which he called “the morgue”) as fiddling, senile, befuddled "director-Neros" who were “habitually in a state of profound alcoholic intoxication”. A university president was described as a “mental delinquent….dumb bunny, false alarm, phony”[6]. In return, Barnes himself was regarded by his enemies as one of the more offensive men in public life. One museum director, after losing a bidding war with Barnes, concluded that “there is no use entering into a pissing contest with a skunk”[7].

Barnes’ idiosyncratic views were also reflected in his response to those who sought permission to view the collection. Officially, access was limited to students at the Foundation, but Barnes exercised his discretion – in a characteristically eccentric way – to admit others. So, for example, he would welcome visitors like Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann or the actor Charles Laughton, but would refuse admission to other notables on the deliberately facetious basis that he was too busy trying to “break the world’s record for goldfish-swallowing”[8], or that he was “out on the lawn singing to the birds” [9]. One rejected journalist was accused of being “either a colossal ignoramus or a demonstrable liar”. TS Eliot received the one-word rejection, “Nuts”; Le Corbusier fared even worse, with “Merde”[10]. Sometimes Barnes signed rejections in the name of his fictional secretary, or even his dog Fidèle-de-Port-Manech who, Barnes claimed, could understand only French [11].

Because of these aberrations, it is all too easy to be critical of Barnes. As a necessary balancing of the ledger, it should be pointed out that in addition to his phenomenal self-made business success, he was an early and active supporter of disadvantaged groups, including Afro-Americans, provided generous employee conditions and benefits for his workforce (which he ensured were mixed-sex and racially integrated), and had a great and genuine commitment to worker education. Barnes was fluent in French, a skilful, even fascinating, lecturer, and displayed impeccable taste and judgment in his collecting [12]. He also studied and wrote widely on art [13]. As Howard Greenfeld points out in The Devil and Dr Barnes, “If Barnes had peacefully collected his paintings, written his books, and directed the educational work of the Foundation, he would have been unqualifiedly respected and universally mourned”[14].

Barnes meets Matisse: 1930

In 1930, the opportunity came for Barnes to meet up with Henri Matisse. Both men would have looked forward to this. Matisse himself was keen to visit the famous collection in which his works featured so prominently. For his part, Barnes was keen to show off the collection to an artist he deeply admired.

The opportunity arose when Matisse was invited to go to New York to help judge the Carnegie Medal. At the time, Matisse had just turned 60, and was at somewhat of a crossroads [15]. Artistically, he had lost some of his inspiration for painting. He had recently returned from a trip to Tahiti, which had been intended to recharge his batteries, but from which he derived few short-term results. He had painted very little – instead mainly concentrating on etching and sculpture – and finished even less; he had, for example, been trying unsuccessfully to finish The Yellow Dress since 1929. He had also been subject to devastating criticism from some critics that he had been coasting, particularly during his so-called Nice period, and that his best days were long behind him[16].

Financially, too, there were problems. He was badly affected by the fall in art prices resulting from the Crash. Coupled with his dwindling stocks of painting, this meant some financial pain for Matisse. To top things off, his home life was also troubled at the time. His wife was an invalid and his adult children were still emotional and financial burdens [17].

Against this depressing background, Matisse welcomed the chance to visit America, and visit one of his most serious collectors. Despite Barnes’ prickly reputation, the two men initially got on well, and Matisse was pleasantly stunned when Barnes asked him to decorate a large area of the two-storey main gallery at Merion. After some bargaining, both parties probably got a reasonable deal – $30,000 in three instalments for an expected year’s work ($10,000 down, $10,000 on half completion and $10,000 on installation) [18]. This was a welcome break for Matisse, and he saw it as a chance to raise his profile and reach out to a new public in America. For an artist who had largely been involved with small, private art, he was excited at this new challenge of producing public, monumental art.

The opportunity arose when Matisse was invited to go to New York to help judge the Carnegie Medal. At the time, Matisse had just turned 60, and was at somewhat of a crossroads [15]. Artistically, he had lost some of his inspiration for painting. He had recently returned from a trip to Tahiti, which had been intended to recharge his batteries, but from which he derived few short-term results. He had painted very little – instead mainly concentrating on etching and sculpture – and finished even less; he had, for example, been trying unsuccessfully to finish The Yellow Dress since 1929. He had also been subject to devastating criticism from some critics that he had been coasting, particularly during his so-called Nice period, and that his best days were long behind him[16].

Financially, too, there were problems. He was badly affected by the fall in art prices resulting from the Crash. Coupled with his dwindling stocks of painting, this meant some financial pain for Matisse. To top things off, his home life was also troubled at the time. His wife was an invalid and his adult children were still emotional and financial burdens [17].

Against this depressing background, Matisse welcomed the chance to visit America, and visit one of his most serious collectors. Despite Barnes’ prickly reputation, the two men initially got on well, and Matisse was pleasantly stunned when Barnes asked him to decorate a large area of the two-storey main gallery at Merion. After some bargaining, both parties probably got a reasonable deal – $30,000 in three instalments for an expected year’s work ($10,000 down, $10,000 on half completion and $10,000 on installation) [18]. This was a welcome break for Matisse, and he saw it as a chance to raise his profile and reach out to a new public in America. For an artist who had largely been involved with small, private art, he was excited at this new challenge of producing public, monumental art.

The difficulties of the Dance

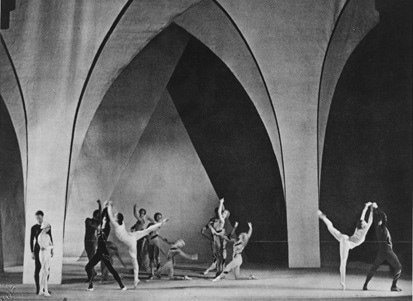

Barnes’ main gallery was impressive in its size and contents. On one wall, directly below the place where Matisse’s work would appear, were his own Seated Riffian (1912/13) and Picasso’s The Peasants (1906). The facing wall featured works by Cezanne and Renoir. On one end wall were Cezanne’s The Card Players (1890/92) and Seurat’s The Models (1887/88) (Fig 2).

The particular space in the gallery that Matisse had to deal with was very large and difficult – about 14 metres long and 3 ½ metres high, a total of about 50 square metres. It was also about 5 metres above floor level. The space was divided into three lunettes by projecting shafts of masonry. It was erratically lit – obscured from above by the shadow of the ceiling vaults, and from below by sunlight pouring in through three glass window/doors. It would actually be quite difficult to see the work fully from ground level. Most viewers would have to feel its presence rather than examine it.

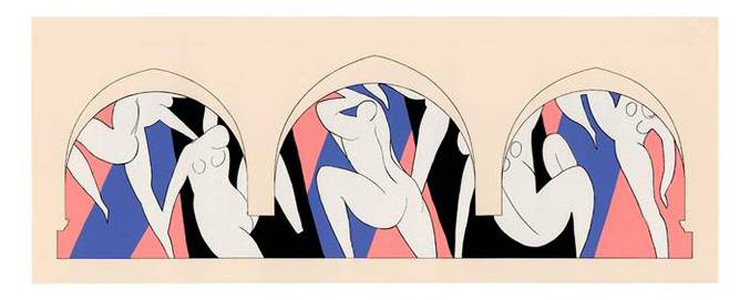

Matisse was given a free choice of subject. He decided on a single composition with the theme of the dance. For Matisse, the dance was associated with vitality and regeneration, and had been a recurring theme in his life. It had of course been the subject of his first major commission, Dance (1909/10). That in turn had partly been inspired by the dance motif in his own Bonheur de Vivre (1905/06), a work which was already in the Barnes collection. Matisse’s aim was to use this theme to produce a work that straddled painting and architecture. It would be the biggest painting that Matisse had ever undertaken, and would be his first picture of figures in motion for more than twenty years [19].

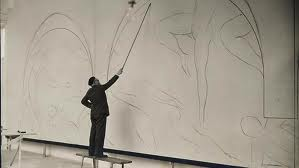

The massive size of the work meant that Matisse could not work on it on-site. Instead he hired a large garage back in Nice, had the walls painted to duplicate plaster and had the massive canvases set up. Then he started doing freehand drafting directly onto the canvases, using a stick of charcoal tied to a bamboo pole (Fig 3).

Matisse was given a free choice of subject. He decided on a single composition with the theme of the dance. For Matisse, the dance was associated with vitality and regeneration, and had been a recurring theme in his life. It had of course been the subject of his first major commission, Dance (1909/10). That in turn had partly been inspired by the dance motif in his own Bonheur de Vivre (1905/06), a work which was already in the Barnes collection. Matisse’s aim was to use this theme to produce a work that straddled painting and architecture. It would be the biggest painting that Matisse had ever undertaken, and would be his first picture of figures in motion for more than twenty years [19].

The massive size of the work meant that Matisse could not work on it on-site. Instead he hired a large garage back in Nice, had the walls painted to duplicate plaster and had the massive canvases set up. Then he started doing freehand drafting directly onto the canvases, using a stick of charcoal tied to a bamboo pole (Fig 3).

The work proved exhausting and the project dragged on. Months into the project, Matisse came to realise that he needed to substantially modify his original design. In effect, this meant that he had to start again. To obviate the practical problems of dealing with multiple changes, he resorted to using paper cutouts He hired a housepainter to cover many large sheets of paper in the limited range of colours Matisse had by now selected – blue, grey, black and pink. Matisse then redrew his entire design, outlining shapes on the coloured paper. His assistant would cut out the shapes in the appropriate colour and pin them on the canvas. To change the design or the arrangement of colour, Matisse would simply draw over the paper and an assistant would trim or add the paper to fit. The work gradually became a giant collage.

Almost a year after he began, when he was nearly finished, a further, disastrous error was discovered. Almost unbelievably, Matisse had made the decoration the wrong size. He had underestimated the width of the pendentives by well over a metre. Again, he was forced to started all over again. Ultimately, the design was not finally completed until March 1933 – more than two years since it was begun. A housepainter was called in again to assist with painting in the outlines at the Merion gallery. The painting was finished off by Matisse, who also added linear accents in charcoal, and some shadowing of the figures, so as to “enliven” the composition. By this stage he was so stressed that he abandoned plans to exhibit the work in Paris before transporting it to America.

Almost a year after he began, when he was nearly finished, a further, disastrous error was discovered. Almost unbelievably, Matisse had made the decoration the wrong size. He had underestimated the width of the pendentives by well over a metre. Again, he was forced to started all over again. Ultimately, the design was not finally completed until March 1933 – more than two years since it was begun. A housepainter was called in again to assist with painting in the outlines at the Merion gallery. The painting was finished off by Matisse, who also added linear accents in charcoal, and some shadowing of the figures, so as to “enliven” the composition. By this stage he was so stressed that he abandoned plans to exhibit the work in Paris before transporting it to America.

Events surrounding the actual installation of the painting at Merion were also fraught. Barnes would not agree with Matisse’s request to remove the two paintings on the wall below. He also refused to replace the frosted glass with clear so as to let the colours of the garden in, or to remove the ornamental frieze at the base of the mural. The tension became so great that, during the installation, Matisse suffered a seizure [20].

Yet the final bombshell was still to come. Although Barnes did not express dissatisfaction with the work, he shocked Matisse by telling him that he had no intention of letting the public see it. Matisse was naturally devastated, describing Barnes privately as a “monster of egotism" who was concerned only with the mixed reception that had greeted his recently-released The Art of Henri-Matisse [21]. Matisse was keen for critical approval and, apart from that, felt strongly that a painting was a form of communication that was wasted if it was not seen. The upsetting result was that, once Matisse left Merion, he never saw the painting again [22]. Very few others did either, until well after Barnes’ death. Even colour reproductions of the painting, like other works at Merion, were strictly forbidden [22a].

Yet the final bombshell was still to come. Although Barnes did not express dissatisfaction with the work, he shocked Matisse by telling him that he had no intention of letting the public see it. Matisse was naturally devastated, describing Barnes privately as a “monster of egotism" who was concerned only with the mixed reception that had greeted his recently-released The Art of Henri-Matisse [21]. Matisse was keen for critical approval and, apart from that, felt strongly that a painting was a form of communication that was wasted if it was not seen. The upsetting result was that, once Matisse left Merion, he never saw the painting again [22]. Very few others did either, until well after Barnes’ death. Even colour reproductions of the painting, like other works at Merion, were strictly forbidden [22a].

Barnes meets Bertrand Russell: 1940

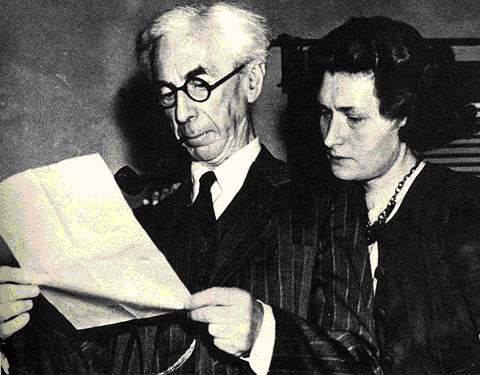

Some seven years later, Barnes came into contact with another iconic figure, Bertrand Russell. As with Matisse, it was an episode that would have far-reaching consequences for both parties.

Russell, born of aristocratic but radical parents, was a leading British philosopher and logician, a prominent anti-war and anti-nuclear activist and a social critic [23]. He held “progressive” views on religion, marriage and sexual morality. Despite his prominence, his experience as a academic was surprisingly modest and his main source of income was as a freelance writer and journalist. In 1938, with a world war looming, and wishing to boost his academic career, he moved to America where he took up appointments at the University of Chicago, and later at UCLA. Neither was an outstanding success, and in 1940 he resigned from UCLA to take up a promising professorship at the College of the City of New York.

The appointment, however, prompted a extraordinary blitz of opposition, orchestrated largely by the Episcopal Bishop of New York, Dr William Manning [24]. The two men had clashed previously, when Manning had campaigned, on moral grounds, against a 1929 lecture tour by Russell. Manning was outraged that his old foe – whom he described as a recognised propagandist against both religion and morality, and as a defender of adultery – was now being honoured by this prestigious new appointment.

The anti-Russell campaign was conducted with “astonishing ferocity”[25], with various editorials, letters and speakers variously condemning him as a Communist, a dog, “ a professor of paganism”, and a “desiccated, divorced and decadent advocate of sexual promiscuity”. On the other hand, Russell was supported by bodies such as the American Civil Liberties Union, a rally of 2,000 at City College, and intellectuals such as Albert Einstein, who famously commented at the time that “great spirits have always encountered violent opposition from mediocre minds”[26].

Despite the extraordinary controversy, the Board of Higher Education confirmed the appointment. However, this simply prompted a court challenge the following day, brought by a Mrs Jean Kay. Although having no connection whatsoever with the College, she opposed the appointment on the grounds that Russell, as a non-citizen, was not legally eligible to take it up. Furthermore, she claimed, his teachings constituted “a danger and a menace to the health, morals and welfare of his students”[27]. In a supporting affidavit, her lawyer made various extravagant allegations, including that Russell had run a “nudist school” and “winked at homosexuality”. Based on earlier books written by Russell some time before [28], the lawyer described Russell as “lecherous, salacious, libidinous, lustful, venerous, erotomaniac, aphrodisiac, atheistic, irreverent, narrow minded, bigoted and untruthful”. There was much more along the same lines [29].

Russell, born of aristocratic but radical parents, was a leading British philosopher and logician, a prominent anti-war and anti-nuclear activist and a social critic [23]. He held “progressive” views on religion, marriage and sexual morality. Despite his prominence, his experience as a academic was surprisingly modest and his main source of income was as a freelance writer and journalist. In 1938, with a world war looming, and wishing to boost his academic career, he moved to America where he took up appointments at the University of Chicago, and later at UCLA. Neither was an outstanding success, and in 1940 he resigned from UCLA to take up a promising professorship at the College of the City of New York.

The appointment, however, prompted a extraordinary blitz of opposition, orchestrated largely by the Episcopal Bishop of New York, Dr William Manning [24]. The two men had clashed previously, when Manning had campaigned, on moral grounds, against a 1929 lecture tour by Russell. Manning was outraged that his old foe – whom he described as a recognised propagandist against both religion and morality, and as a defender of adultery – was now being honoured by this prestigious new appointment.

The anti-Russell campaign was conducted with “astonishing ferocity”[25], with various editorials, letters and speakers variously condemning him as a Communist, a dog, “ a professor of paganism”, and a “desiccated, divorced and decadent advocate of sexual promiscuity”. On the other hand, Russell was supported by bodies such as the American Civil Liberties Union, a rally of 2,000 at City College, and intellectuals such as Albert Einstein, who famously commented at the time that “great spirits have always encountered violent opposition from mediocre minds”[26].

Despite the extraordinary controversy, the Board of Higher Education confirmed the appointment. However, this simply prompted a court challenge the following day, brought by a Mrs Jean Kay. Although having no connection whatsoever with the College, she opposed the appointment on the grounds that Russell, as a non-citizen, was not legally eligible to take it up. Furthermore, she claimed, his teachings constituted “a danger and a menace to the health, morals and welfare of his students”[27]. In a supporting affidavit, her lawyer made various extravagant allegations, including that Russell had run a “nudist school” and “winked at homosexuality”. Based on earlier books written by Russell some time before [28], the lawyer described Russell as “lecherous, salacious, libidinous, lustful, venerous, erotomaniac, aphrodisiac, atheistic, irreverent, narrow minded, bigoted and untruthful”. There was much more along the same lines [29].

The judge, John E McGeehan, apparently glossing over various procedural irregularities in the proceedings, speedily revoked Russell’s appointment to what he described as a “chair of indecency”, ruling that Russell had openly encouraged illegal acts (adultery was a criminal office in New York at the time) and was morally unfit to teach philosophy [30]. This was so even though Russell’s proposed lectures were limited to the seemingly dry topics of logic, and the philosophy of mathematics and science. As it happened, Russell had actually changed his views on adultery by this time in any event, though, interestingly, he was not permitted to appear before the court even had he so wished.

McGeehan also had little time for arguments based on the emerging concept of academic freedom. He stressed that this had to be distinguished from academic license, and came to the rather remarkable conclusion that academic freedom meant only the “the freedom to do good and not to teach evil”[31].

Despite various abortive appeals, the decision stood. Russell was left with no permanent job to go to. At 68 years old, his academic career appeared to be over. He needed money. And his home life, with his third wife Patricia, was proving difficult. In many ways, it was a similar scenario to that in which Matisse had found himself back in 1930.

McGeehan also had little time for arguments based on the emerging concept of academic freedom. He stressed that this had to be distinguished from academic license, and came to the rather remarkable conclusion that academic freedom meant only the “the freedom to do good and not to teach evil”[31].

Despite various abortive appeals, the decision stood. Russell was left with no permanent job to go to. At 68 years old, his academic career appeared to be over. He needed money. And his home life, with his third wife Patricia, was proving difficult. In many ways, it was a similar scenario to that in which Matisse had found himself back in 1930.

Barnes to the rescue again

Help was, however at hand, and again it came from Barnes. An invitation arrived for Russell to join the Barnes Foundation as a philosophy lecturer. It was a lucrative offer for little work – just one lecture a week for five years – and Russell was pleased to take it [32].

The educational work of the Foundation was inextricably linked to the collection. Classes were small, conducted primarily at Merion. The admissions policy was rather haphazard, with applicants from poor or ethnic backgrounds being particularly favoured, and with seemingly arbitrary inclusions and exclusions. Even after being accepted, students could be expelled for absenteeism, late arrivals or disagreement with Barnes’ theories. Barnes also maintained a similarly rigid control over the faculty staff [33].

At the time of Russell’s appointment, Barnes appears to have felt that the two men had much in common. He likened Russell’s court battle to the “bitter medicine” that he himself had experienced when “the principal Philadelphia newspaper printed an editorial denouncing me as a ‘perverter of public morals’ because I exhibited, wrote and talked about such painters as Cezanne and Renoir” [34]. He made Russell an undertaking that “if you say what you damn well please, even giving your adversaries a dose of their own medicine, we’ll back you up”.

In this, however, Barnes had seriously misread Russell. As Russell’s biographer Ray Monk points out, Russell did not particularly want Barnes to be his friend or even his colleague. He saw the relationship with Barnes simply “an opportunity to realise the kind of quiet, financially secure, contemplative life that was required to pursue serious work. He did not want to fight Barnes’ battles, nor did he want Barnes to fight his; he wanted only to work in peace in the countryside, undisturbed by the demands of working journalism or engaging in polemics”[35]. Privately, while grateful to his “rich patron”, he was somewhat contemptuous of him, and would later ridicule Barnes’ mispronunciations of the names of pre-Socratic philosophers [36].

The educational work of the Foundation was inextricably linked to the collection. Classes were small, conducted primarily at Merion. The admissions policy was rather haphazard, with applicants from poor or ethnic backgrounds being particularly favoured, and with seemingly arbitrary inclusions and exclusions. Even after being accepted, students could be expelled for absenteeism, late arrivals or disagreement with Barnes’ theories. Barnes also maintained a similarly rigid control over the faculty staff [33].

At the time of Russell’s appointment, Barnes appears to have felt that the two men had much in common. He likened Russell’s court battle to the “bitter medicine” that he himself had experienced when “the principal Philadelphia newspaper printed an editorial denouncing me as a ‘perverter of public morals’ because I exhibited, wrote and talked about such painters as Cezanne and Renoir” [34]. He made Russell an undertaking that “if you say what you damn well please, even giving your adversaries a dose of their own medicine, we’ll back you up”.

In this, however, Barnes had seriously misread Russell. As Russell’s biographer Ray Monk points out, Russell did not particularly want Barnes to be his friend or even his colleague. He saw the relationship with Barnes simply “an opportunity to realise the kind of quiet, financially secure, contemplative life that was required to pursue serious work. He did not want to fight Barnes’ battles, nor did he want Barnes to fight his; he wanted only to work in peace in the countryside, undisturbed by the demands of working journalism or engaging in polemics”[35]. Privately, while grateful to his “rich patron”, he was somewhat contemptuous of him, and would later ridicule Barnes’ mispronunciations of the names of pre-Socratic philosophers [36].

The relationship unravels

Russell’s lectures, on the history of philosophy, proved to be spectacularly successful, with over 500 applicants to attend the course. However, perhaps inevitably, cracks in his relationship with Barnes soon started to appear.

The initial causes appeared fairly trivial. Russell’s wife Patricia [37] appeared to take her acquired aristocratic status [38] very seriously, sometimes insisting on being addressed as Lady Russell and adopting what Barnes regarded as a superior and snobbish attitude [39]. This did not go down well at the professedly democratic Barnes Foundation. There were complaints raised that Patricia had “created a disturbance” by knitting during Russell’s lectures (!), that she had burst in interrupting a press interview, and generally that she had “trouble-making propensities”. After a prickly exchange of correspondence, she was ultimately banned from entering the Foundation’s premises. The position worsened considerably when a full account of the dispute, generally favouring the Russells, was published in the Saturday Evening Post, much to Barnes’ fury [40].

The breaking point finally came in 1942 when Russell agreed to give a series of weekly lectures with the Rand School of Social Science. Barnes took the view – ultimately incorrectly – that this was in breach of his contract with Russell, and peremptorily dismissed him, with only three days’ notice. The stunned Russell was, in his words, “reduced once again from affluence to destitution” [41]. At the age of seventy, he felt that he might be forced to return to wartime England or starve [42].

The initial causes appeared fairly trivial. Russell’s wife Patricia [37] appeared to take her acquired aristocratic status [38] very seriously, sometimes insisting on being addressed as Lady Russell and adopting what Barnes regarded as a superior and snobbish attitude [39]. This did not go down well at the professedly democratic Barnes Foundation. There were complaints raised that Patricia had “created a disturbance” by knitting during Russell’s lectures (!), that she had burst in interrupting a press interview, and generally that she had “trouble-making propensities”. After a prickly exchange of correspondence, she was ultimately banned from entering the Foundation’s premises. The position worsened considerably when a full account of the dispute, generally favouring the Russells, was published in the Saturday Evening Post, much to Barnes’ fury [40].

The breaking point finally came in 1942 when Russell agreed to give a series of weekly lectures with the Rand School of Social Science. Barnes took the view – ultimately incorrectly – that this was in breach of his contract with Russell, and peremptorily dismissed him, with only three days’ notice. The stunned Russell was, in his words, “reduced once again from affluence to destitution” [41]. At the age of seventy, he felt that he might be forced to return to wartime England or starve [42].

The silver-lined sequels

Both of these episodes, although several years apart, had followed an uncannily similar arc. For both Matisse and Russell, their encounters with Dr Barnes had started at a low point in their personal and professional lives. In both cases, this had been followed by the promise of rescue with a lucrative job offer from Barnes. However, after an initial amicable period, each of their relationships with Barnes would suffer a dramatic breakdown. Despite this, in both cases, that relationship would result in breakthroughs that would prove pivotal to their future careers.

For Matisse, upset as he may have been in 1933, the Dance itself was, in his eyes, an artistic success, and – especially in retrospect – he was grateful to Barnes for giving him the chance to express himself on a grand scale. As Matisse rather expansively said, he would happily live on bread and water if he had another wall to decorate [43].

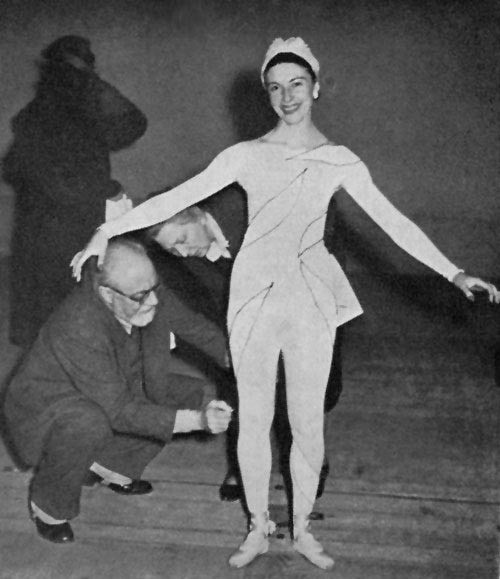

On a more general level, too, there were major positives for Matisse. Some commentators consider that the Barnes commission was pivotal in enabling Matisse to return to the most essential sources of his art [44]. Indeed, one suggests that the Barnes commission was a “time bomb” that catapulted Matisse back towards his glorious pre-Nice past, and in doing so cleared the way for the future [45]. Whatever the merits of these claims, it does seem fair to say that, for Matisse, the Barnes commission served to highlight the importance of simplicity, abstractness, flattening, the emphasis on colour at the expense of traditional line, and the use of paper cut-outs. Although largely prompted by the particularly architectural demands of the commission itself, there is little doubt that these trends would go on to play an important role in reviving Matisse’s career and later artistic development. They would also have application in his other fields of artistic interest -- in 1938 he was even using Dance-style motifs of paper cut-outs and arched backgrounds in his design of Léonide Massine's ballet Rouge et Noir.

For Matisse, upset as he may have been in 1933, the Dance itself was, in his eyes, an artistic success, and – especially in retrospect – he was grateful to Barnes for giving him the chance to express himself on a grand scale. As Matisse rather expansively said, he would happily live on bread and water if he had another wall to decorate [43].

On a more general level, too, there were major positives for Matisse. Some commentators consider that the Barnes commission was pivotal in enabling Matisse to return to the most essential sources of his art [44]. Indeed, one suggests that the Barnes commission was a “time bomb” that catapulted Matisse back towards his glorious pre-Nice past, and in doing so cleared the way for the future [45]. Whatever the merits of these claims, it does seem fair to say that, for Matisse, the Barnes commission served to highlight the importance of simplicity, abstractness, flattening, the emphasis on colour at the expense of traditional line, and the use of paper cut-outs. Although largely prompted by the particularly architectural demands of the commission itself, there is little doubt that these trends would go on to play an important role in reviving Matisse’s career and later artistic development. They would also have application in his other fields of artistic interest -- in 1938 he was even using Dance-style motifs of paper cut-outs and arched backgrounds in his design of Léonide Massine's ballet Rouge et Noir.

For Bertrand Russell, despite his initial despair at his dismissal, he too ended up substantially benefiting from his relationship with Barnes in a number of ways. After receiving legal advice, he had successfully sued Barnes for wrongful dismissal, securing damages for the loss of virtually all the wages due to him under the unexpired part of the contract, a sum of $20,000 [46]. In addition, the lectures that Russell had given at the Barnes Foundation would form the basis of his A History of Western Philosophy, first published in 1945. Apart from gaining him the largest advance he had ever received, this book proved to be a great commercial success (despite mixed critical reviews) and provided Russell with considerable financial security for the rest of his life. It was also one of the four works mentioned when Russell was, rather unexpectedly, awarded the 1950 Nobel Prize for Literature “in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought” [47]. This book, which Russell acknowledged as owing its existence to Barnes, therefore played a significant part in the revival of Russell’s career [48].

Russell’s academic career had also received a substantial boost. After the dismissal from the Barnes Foundation, the Russells re-established contact with Trinity College in Cambridge, with whom there had been a serious breach for more than 20 years. The upshot, in early 1944, was what Monk describes as “some extraordinarily good news” – the offer of a five year fellowship at Trinity, which would enable Russell to pursue his work in “the most congenial circumstances imaginable” [49]. His academic future was assured.

Meanwhile, for Barnes himself, life returned to “normal”. The work of the Foundation continued, as did his disputes with his traditional enemies. Barnes, however, was slowing with age, and became pre-occupied with finding an institution qualified to assume responsibility for this collection after his death. He died in a motor vehicle accident in 1951, with the issue still not finally settled. Almost unbelievably, acrimonious disputes about the future of the collection continued for years, finally resulting in the contentious 2012 removal of the entire collection to new premises in downtown Philadelphia, where it was rehung in virtually the same manner [50].

Russell’s academic career had also received a substantial boost. After the dismissal from the Barnes Foundation, the Russells re-established contact with Trinity College in Cambridge, with whom there had been a serious breach for more than 20 years. The upshot, in early 1944, was what Monk describes as “some extraordinarily good news” – the offer of a five year fellowship at Trinity, which would enable Russell to pursue his work in “the most congenial circumstances imaginable” [49]. His academic future was assured.

Meanwhile, for Barnes himself, life returned to “normal”. The work of the Foundation continued, as did his disputes with his traditional enemies. Barnes, however, was slowing with age, and became pre-occupied with finding an institution qualified to assume responsibility for this collection after his death. He died in a motor vehicle accident in 1951, with the issue still not finally settled. Almost unbelievably, acrimonious disputes about the future of the collection continued for years, finally resulting in the contentious 2012 removal of the entire collection to new premises in downtown Philadelphia, where it was rehung in virtually the same manner [50].

Conclusion

In a sense, Barnes had attempted to “collect” Matisse and Russell, just as he had collected great paintings. The fact that neither relationship worked out precisely as planned – though ultimately very beneficially for both Matisse and Russell – may be due to the fact that Barnes got on better with paintings than he did with people. Barnes himself recognised this. Indeed, he celebrated it. As far back as 1915, in his first work of art criticism, he wrote, “Good paintings are much more satisfying companions than the best of books and infinitely more so than most very nice people”. Unlike people, paintings also had the unique advantage of being able to inform or even correct Barnes without openly disagreeing with him. "That", said Barnes, "is one of the joys of a collection” [51]. □

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017

We welcome your comments on this article

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017

We welcome your comments on this article

End notes

[1] Quotations from the New York Herald Tribune, the New York Times and Art News, cited in Greenfeld, H, The Devil and Dr Barnes: Portrait of an American Art Collector, Penguin Books, New York 1987, at 1.

[2] For a full account of Barnes’ life, see Greenfeld, op cit.

[3] Greenfeld, op cit at 54.

[4] Greenfeld, op cit at 73. See also the Barnes Foundation website at www.barnesfoundation.org

[5] Greenfeld, op cit at 129.

[6] Greenfeld, op cit at 118, 277..

[7] Spurling, H, Matisse the Master, Penguin Books, London, 2006 at 324, quoting the Director of Philadelphia Museum of Art, as cited by Lukacs, J, Philadelphia: Patricians and Philistines 1900-1950, New York, 1980 at 271.

[8] Greenfeld, op cit at 129-130. The rejectee was the millionaire collector Walter Chrysler Jr.

[9] Greenfeld, op cit at 254. The rejectee was the critic and playwright Alexander Woollcott.

[10] Greenfeld, op cit at 252-3.

[11] Monk, R, Bertrand Russell 1921-70: the Ghost of Madness, Jonathan Cape, London, 2000, at 248. Above the dog’s bed was a map of Brittany, “in case he felt lost”: Greenfeld, op cit at 283.

[12] See generally Greenfeld, op cit.

[13] For example The Art in Painting (1925); The Art of Henri-Matisse (1933).

[14] Greenfeld, op cit at 3.

[15] Spurling, op cit at 322ff.

[16] Bois, Y-A, “The Shift”, in Turner and Benjamin, eds, Matisse, Brisbane: QAG, 1995 at 97.

[17] Spurling, op cit at 322.

[18] This would be over $400,000 in today’s values. For further details, see Flam, J, Matisse: The Dance, Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1993.

[19] In relation to execution of the Dance mural, see generally Flam, op cit and Spurling, op cit at 329 -336.

[20] Flam, op cit at 62; Spurling, op cit at 336.

[21] Spurling, op cit at 337. Barnes made no public pronouncement on the Dance mural, and the work is not mentioned in his book.

[22] Spurling, op cit at 338.

[22a] The Dance was physically removed and relocated to the new Barnes Museum in 2012. See the item "Barnes' controversial reopening in downtown Philadelphia" in Art News.

[23] For a full account of Russell’s life, see Monk, R, Bertrand Russell 1921-70: the Ghost of Madness, Jonathan Cape, London, 2000; and its companion volume Bertrand Russell: the Spirit of Solitude.

[24] Monk, op cit at 230.

[25] Monk, op cit at 232.

[26] Einstein continued: “The mediocre mind is incapable of understanding the man who refuses to bow blindly to conventional prejudices and chooses instead to express his opinions courageously and honestly”: letter to Morris Raphael Cohen, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at College of the City of New York, March 1940.

[27] Monk, op cit at 235.

[28] Marriage and Morals, On Education, What I Believe and Education and the Modern World.

[29] Monk, op cit at 236.

[30] Kay v. Board of Higher Ed. of City of New York, 18 N.Y.S.2d 821 (1940).

[31] Kay, op cit at 829.

[32] Monk, op cit at 247.

[33] Greenfeld, op cit at 231.

[34] Monk, op cit at 247.

[35] Monk, op cit at 249.

[36] Monk, op cit at 245.

[37] Oddly, she was known as “Peter”, apparently because her parents had always wanted a boy: Monk, op cit at 118.

[38] Russell had inherited an earldom in 1931.

[39] Monk, op cit at 261.

[40] Monk, op cit at 262. The article, “The Terrible-Tempered Dr Barnes”, by Carl W McCardle, was published over the March 21, March 28, April 4 and April 11 1942 issues of the magazine. At one point it described Barnes as a “combination of Peck’s Bad Boy and Donald Duck”, who was said to get “his greatest personal satisfaction out of writing poison-pen letters”.

[41] Greenfeld, op cit at 222.

[42] Greenfeld, op cit at 226.

[43] Flam, op cit at 74.

[44] Flam, op cit at 76-77; Bois, op cit at 98.

[45] Bois, op cit at 98. Though it must be said that In view of the time Matisse spent on the commission, it must have been a remarkably slow-acting bomb.

[46] Monk, op cit at 265.

[47] Monk, op cit at 332.

[48] In the Preface, Russell states that, “This book owes its existence to Dr Alfred C Barnes, having been originally designed and partly delivered as lectures at the Barnes Foundation in Pennsylvania”: A History of Western Philosophy, Unwin Paperbacks, London, 1979 at 8.

[49] Monk, op cit at 271.

[50] For an account of the ongoing disputes, see Anderson, J, Art Held Hostage: the Battle over the Barnes Collection, WW Norton and Company, New York, 2003. For reaction to the move, see the item "Barnes' controversial reopening in downtown Philadelphia" in Art News. For an excellent guide to the collection in in its new home, see Dolkart, J F and ors, The Barnes Foundation: Masterworks, Skira Rizzoli, 2012. For a PBS documentary on Barnes' life and his collection, including its move downtown, see The Barnes Collection (dir Glenn Holsten).

[51] Barnes, A C, “How to Judge a Painting”, Arts and Decoration April 1915, cited in Greenfeld, op cit at 53-4.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Strange encounters; The Collector, the Artist and the Philosopher", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home

[2] For a full account of Barnes’ life, see Greenfeld, op cit.

[3] Greenfeld, op cit at 54.

[4] Greenfeld, op cit at 73. See also the Barnes Foundation website at www.barnesfoundation.org

[5] Greenfeld, op cit at 129.

[6] Greenfeld, op cit at 118, 277..

[7] Spurling, H, Matisse the Master, Penguin Books, London, 2006 at 324, quoting the Director of Philadelphia Museum of Art, as cited by Lukacs, J, Philadelphia: Patricians and Philistines 1900-1950, New York, 1980 at 271.

[8] Greenfeld, op cit at 129-130. The rejectee was the millionaire collector Walter Chrysler Jr.

[9] Greenfeld, op cit at 254. The rejectee was the critic and playwright Alexander Woollcott.

[10] Greenfeld, op cit at 252-3.

[11] Monk, R, Bertrand Russell 1921-70: the Ghost of Madness, Jonathan Cape, London, 2000, at 248. Above the dog’s bed was a map of Brittany, “in case he felt lost”: Greenfeld, op cit at 283.

[12] See generally Greenfeld, op cit.

[13] For example The Art in Painting (1925); The Art of Henri-Matisse (1933).

[14] Greenfeld, op cit at 3.

[15] Spurling, op cit at 322ff.

[16] Bois, Y-A, “The Shift”, in Turner and Benjamin, eds, Matisse, Brisbane: QAG, 1995 at 97.

[17] Spurling, op cit at 322.

[18] This would be over $400,000 in today’s values. For further details, see Flam, J, Matisse: The Dance, Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1993.

[19] In relation to execution of the Dance mural, see generally Flam, op cit and Spurling, op cit at 329 -336.

[20] Flam, op cit at 62; Spurling, op cit at 336.

[21] Spurling, op cit at 337. Barnes made no public pronouncement on the Dance mural, and the work is not mentioned in his book.

[22] Spurling, op cit at 338.

[22a] The Dance was physically removed and relocated to the new Barnes Museum in 2012. See the item "Barnes' controversial reopening in downtown Philadelphia" in Art News.

[23] For a full account of Russell’s life, see Monk, R, Bertrand Russell 1921-70: the Ghost of Madness, Jonathan Cape, London, 2000; and its companion volume Bertrand Russell: the Spirit of Solitude.

[24] Monk, op cit at 230.

[25] Monk, op cit at 232.

[26] Einstein continued: “The mediocre mind is incapable of understanding the man who refuses to bow blindly to conventional prejudices and chooses instead to express his opinions courageously and honestly”: letter to Morris Raphael Cohen, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at College of the City of New York, March 1940.

[27] Monk, op cit at 235.

[28] Marriage and Morals, On Education, What I Believe and Education and the Modern World.

[29] Monk, op cit at 236.

[30] Kay v. Board of Higher Ed. of City of New York, 18 N.Y.S.2d 821 (1940).

[31] Kay, op cit at 829.

[32] Monk, op cit at 247.

[33] Greenfeld, op cit at 231.

[34] Monk, op cit at 247.

[35] Monk, op cit at 249.

[36] Monk, op cit at 245.

[37] Oddly, she was known as “Peter”, apparently because her parents had always wanted a boy: Monk, op cit at 118.

[38] Russell had inherited an earldom in 1931.

[39] Monk, op cit at 261.

[40] Monk, op cit at 262. The article, “The Terrible-Tempered Dr Barnes”, by Carl W McCardle, was published over the March 21, March 28, April 4 and April 11 1942 issues of the magazine. At one point it described Barnes as a “combination of Peck’s Bad Boy and Donald Duck”, who was said to get “his greatest personal satisfaction out of writing poison-pen letters”.

[41] Greenfeld, op cit at 222.

[42] Greenfeld, op cit at 226.

[43] Flam, op cit at 74.

[44] Flam, op cit at 76-77; Bois, op cit at 98.

[45] Bois, op cit at 98. Though it must be said that In view of the time Matisse spent on the commission, it must have been a remarkably slow-acting bomb.

[46] Monk, op cit at 265.

[47] Monk, op cit at 332.

[48] In the Preface, Russell states that, “This book owes its existence to Dr Alfred C Barnes, having been originally designed and partly delivered as lectures at the Barnes Foundation in Pennsylvania”: A History of Western Philosophy, Unwin Paperbacks, London, 1979 at 8.

[49] Monk, op cit at 271.

[50] For an account of the ongoing disputes, see Anderson, J, Art Held Hostage: the Battle over the Barnes Collection, WW Norton and Company, New York, 2003. For reaction to the move, see the item "Barnes' controversial reopening in downtown Philadelphia" in Art News. For an excellent guide to the collection in in its new home, see Dolkart, J F and ors, The Barnes Foundation: Masterworks, Skira Rizzoli, 2012. For a PBS documentary on Barnes' life and his collection, including its move downtown, see The Barnes Collection (dir Glenn Holsten).

[51] Barnes, A C, “How to Judge a Painting”, Arts and Decoration April 1915, cited in Greenfeld, op cit at 53-4.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Strange encounters; The Collector, the Artist and the Philosopher", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home