Art in a Speeded Up World - Part 2

By Philip McCouat

|

Art in a Speeded Up World: Overview

Part 1: Changing concepts of time Part 2: The 'new' time in literature Part 3: The 'new' time in painting |

Other articles on photography:

Early influences of photography on art Why wasn’t photography invented earlier? ------------------------------------------------------------ |

PART 2: THE 'NEW' TIME IN LITERATURE

The pervasiveness of these radical and puzzling changes in conceptions of time, ranging from the cosmic level down to the social and personal, soon inspired writers to explore extraordinary new directions in their work. During the course of the nineteenth century, popular literature moved from the genteel, timeless world of Jane Austen to the wild futuristic imaginings of H G Wells. During this period, a preoccupation with time and its malleability emerged as a major theme in many major literary works.

An obvious example was the emergence of the new genre that would later be described as ‘science fiction’[73]. Emerging from classic Gothic fiction such as Mary Shelley’s groundbreaking Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus (1818)[73a], her futuristic The Last Man (1826) and Jane C Loudon’s totally remarkable The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty Second Century (1827)[73b], science fiction broke new ground by featuring stories set in the future, and by popularising the intriguing concept of time travel. Particularly influential examples included, Dickens’ ‘Our Phantom Ship on an Antediluvian Cruise’ in Household Words (1851), A Christmas Carol (1843), Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864), Pierre Boitard’s fossil- and evolution-based Paris Avant les hommes [Paris before Men] (1861), Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward 2000-1887 (1888) – one of the best-selling books of the nineteenth century – and Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) [74].

Many of these works, particularly the earlier ones, tended to present the time travel as involuntary and sometimes imaginary, with a destination outside the protagonist’s control, and instigated by some surprising mind-altering event such as a dream, the intervention of a ghost or an angel, a blow to the head or an alcoholically-induced stupor [75]. Some influential later works, possibly reflecting the more sophisticated time concepts that been developing, started to involve more physical devices, such as clocks or other time machines, which – at least in theory – could be consciously and deliberately manipulated to enable the protagonist to travel to the desired era. In these works the actual process of time travel, not just the destination, assumes greater importance, as is evident from the titles: the Spaniard Enrique Gaspar y Rimbau’s El Anacropete (1887) (‘flyer against time’), Edward Page Mitchell’s The Clock That Went Backward (1887) and HG Wells’ The Chronic Argonauts (1888), followed by his classic The Time Machine (1895) [76].

Other manipulations of time

Related works, though not involving time travel itself, feature the manipulation of time in various guises. In Wells’ The New Accelerator (1901), a story inspired by the author’s fascination with chronophotography [77], a newly-invented drug enables people to move at such speed that the rest of the world seems virtually frozen in time. The drug’s inventor exclaims, ‘It kicks the theory of vision into a perfectly new shape!’ In Edward Bellamy’s The Blindman’s World (1886), the narrator suddenly finds himself on Mars where he encounters beings who know the future up to their deaths, and have only a rudimentary idea of their past. Page Mitchell’s extraordinary The Tachypomp (1874) explores the possibilities of faster-than-light travel.

Outside science fiction, themes related to the manipulation of time also begin to appear in works such as Lewis Carroll’s phenomenonally successful Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There (1871). In both of these books, reality and identity become contingent, perception becomes highly subjective and there are constant, radical variations in time and size. Time is personified as a ‘he’ which doesn’t like being ‘beaten’, and who responds to requests to speed up. The March Hare is obsessed with time (‘I’m late! I’m late!’), and the Mad Hatter is sentenced to death because ‘He’s murdering the time!’ A watch tells the days of the month, not the hours of the day. The Red Queen inverts the normal time sequence by proclaiming, ‘Sentence first, verdict later!’ and the White Queen proclaims, ‘it’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards’. Alice neatly sums up the twin themes of reality and time shifts: ‘It’s no use going back to yesterday, because I was a different person then’.

The manipulation of time is also central to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Grey (1890), which brings together the themes of an alternative reality and of time ‘frozen’ in a painting. JM Barrie’s play Peter Pan (1904) presents a more literal version of time standing still, in the form of the boy who refused to grow up, a setting – significantly called Neverland – in which the passage of time is ambiguously unreal, and a hungry crocodile that swallows a clock whose ‘tick-tock’ transforms it into an ominous embodiment of passing time [78].

At a more subtle level, Ėdouard Dujardin’s Les Lauriers sont Coupés (1888) rejected strict chronology in favour of free association and a form of the ‘stream of consciousness’ allied to Jamesian concepts [79]. Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866) was based on a minute description of the protagonist’s inner thoughts, with a plot that unfolded over a period shorter than the average reader takes to read it – a concept of a ‘present’ that seemed to continue almost indefinitely [80]. Proust’s monumental In Search of Lost Time, published in stages from 1913 onwards, also ignores the constraints of linear time, intermingling a past and a present, with the present continually triggering the past [81]. In Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier (1915), the reader rather than the protagonist, experiences a form of mental time travel as a result of the author’s radical experimentations in a third person narrative sequence by using ‘flashbacks’ and ‘flash forwards’ in time.

Crime, detection and penny dreadfuls

While the connection is less direct, the extraordinary new sense of immediacy also provided fertile ground for the development of the new genre of crime or detective fiction. This genre involved ‘cleverly constructed stories, the whole interest of which consists in the gradual unravelling of some carefully prepared enigma’[82]. The genre is commonly accepted as first emerging in its modern version in the 1840s, with Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue and other short stories, followed by Wilkie Collins’ novels The Woman in White (1859) and The Moonstone (1868) [83].

Detective fiction contained many intriguing aspects for readers. Firstly, it turned the focus of stories from the adventures of daring criminals (such as Dick Turpin) to the discoveries of brilliant detectives -- in the words of one critical commentator, it developed as ‘a literary institutionalisation of the habits of mind of the new police force’[84]. Secondly, the stories were increasingly driven by plot, and the uncovering of detail, often at the expense of character. Thirdly, and most significantly for our purposes, the approach taken by detectives resembled that taken by the groundbreaking geologists or evolutionists – they began with the present, and then methodically travelled back into the past to uncover the reasons why the present is as it is [85].

Detectives thus became the medium for readers to experience a form of time travel. This had the effect of turning the traditional treatment of tragedy on its head – instead of a character’s fatal flaw leading eventually to an unpleasant and usually inevitable end, detective stories usually started with the unpleasant event and, by working backwards in time, eventually reached a fulfilling conclusion. As Raymond Chandler remarked, ‘a detective story is a tragedy with a happy ending’[86]. The dramatic originality of the genre was indicated by the number of words that needed to be coined or redefined in order for the new stories to be told – not just the word ‘detective’ itself, but also words such as clue, sleuth, hunch, lead and red herring.

The rapid growth in the public’s (and writers’) interest in crime had been fuelled largely by the growth of the popular penny press that we have discussed earlier. Crime provided one of the most sensational sources of material for these publications [87] – as one character in Dickens’ Great Expectations (1861) reads the news, he becomes ‘imbued with blood to the eyebrows’[88]. In turn, these crime reports in turn provided attractive plot lines for authors. As Altick points out, ‘every good new Victorian murder helped legitimise and prolong the fashion of sensational plots’[89].

Around the same time, the development of a British national police force and criminal investigation departments [90], together with the instantaneity provided by telegraphic communication, led to a much more professional and rapid approach to detection and enforcement. To a significant extent, detectives were products of the new time-saving technologies. In one sensational murder case, the dramatic changes flowing from this new time-immediacy were described as ‘almost miraculous’, with the Glasgow Herald breathlessly recounting how a description of the suspect had been sent from London ‘at ten minutes before one o’clock’, and ‘a few minutes after one’ the police were at her door. Then ‘before the clock had struck two’, a telegraph was on its way back to London to report her arrest. ‘So magically had all this been effected’ that the police in London had barely returned to Scotland Yard before the news of the arrest was with them [91].

The stark nature of the change is illustrated by contrasting the investigation of an early 19th century robbery, as presented George Eliot’s Silas Marner, with that of a similar crime occurring a few decades later in 1848, as presented in Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone. The earlier investigation simply involved informing a local magistrate and the eventual setting up of a kind of local committee, with both measures proving to be ineffectual. By contrast, in The Moonstone, the crime was reported by the newly-invented telegraph to the newly-developed Scotland Yard, and the police arrived at the crime scene within hours, travelling by the newly-developed railway [92].

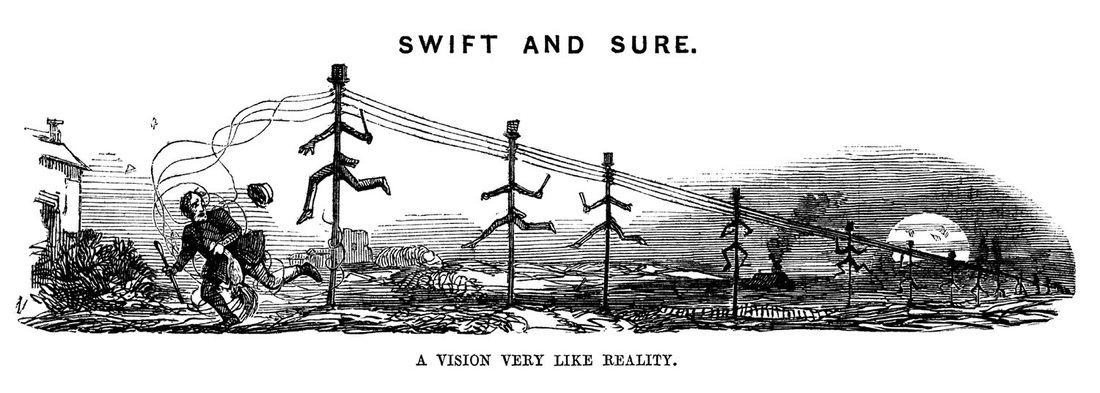

This capacity of telegraph messages and trains to play a dramatic role in criminal investigations generated enormous public interest. In 1845, for example, the murderer John Tawell achieved the twin distinction of becoming the first person to be arrested as the result of telecommunications technology and – reportedly – the first murderer to flee the scene of the crime by rail [93]. After being spotted acting suspiciously and catching a train to London, Tawell had been overtaken by a telegraphic message containing his description, and was consequently arrested by a railway policeman soon after his arrival. The drama, not surprisingly, ‘filled the newspapers for months’[94]. Contemporary commentators were prompted to dub the telegraph as ‘the electric constable’[95],or ‘God’s lightning’[96], and the telegraph lines were described as ‘the cords that hung John Tawell’[97]. One newspaper marvelled at how a ‘guilty wretch, flying on the wings of steam’, could be ‘tracked by a swifter messenger’[98].

An obvious example was the emergence of the new genre that would later be described as ‘science fiction’[73]. Emerging from classic Gothic fiction such as Mary Shelley’s groundbreaking Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus (1818)[73a], her futuristic The Last Man (1826) and Jane C Loudon’s totally remarkable The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty Second Century (1827)[73b], science fiction broke new ground by featuring stories set in the future, and by popularising the intriguing concept of time travel. Particularly influential examples included, Dickens’ ‘Our Phantom Ship on an Antediluvian Cruise’ in Household Words (1851), A Christmas Carol (1843), Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864), Pierre Boitard’s fossil- and evolution-based Paris Avant les hommes [Paris before Men] (1861), Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward 2000-1887 (1888) – one of the best-selling books of the nineteenth century – and Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) [74].

Many of these works, particularly the earlier ones, tended to present the time travel as involuntary and sometimes imaginary, with a destination outside the protagonist’s control, and instigated by some surprising mind-altering event such as a dream, the intervention of a ghost or an angel, a blow to the head or an alcoholically-induced stupor [75]. Some influential later works, possibly reflecting the more sophisticated time concepts that been developing, started to involve more physical devices, such as clocks or other time machines, which – at least in theory – could be consciously and deliberately manipulated to enable the protagonist to travel to the desired era. In these works the actual process of time travel, not just the destination, assumes greater importance, as is evident from the titles: the Spaniard Enrique Gaspar y Rimbau’s El Anacropete (1887) (‘flyer against time’), Edward Page Mitchell’s The Clock That Went Backward (1887) and HG Wells’ The Chronic Argonauts (1888), followed by his classic The Time Machine (1895) [76].

Other manipulations of time

Related works, though not involving time travel itself, feature the manipulation of time in various guises. In Wells’ The New Accelerator (1901), a story inspired by the author’s fascination with chronophotography [77], a newly-invented drug enables people to move at such speed that the rest of the world seems virtually frozen in time. The drug’s inventor exclaims, ‘It kicks the theory of vision into a perfectly new shape!’ In Edward Bellamy’s The Blindman’s World (1886), the narrator suddenly finds himself on Mars where he encounters beings who know the future up to their deaths, and have only a rudimentary idea of their past. Page Mitchell’s extraordinary The Tachypomp (1874) explores the possibilities of faster-than-light travel.

Outside science fiction, themes related to the manipulation of time also begin to appear in works such as Lewis Carroll’s phenomenonally successful Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There (1871). In both of these books, reality and identity become contingent, perception becomes highly subjective and there are constant, radical variations in time and size. Time is personified as a ‘he’ which doesn’t like being ‘beaten’, and who responds to requests to speed up. The March Hare is obsessed with time (‘I’m late! I’m late!’), and the Mad Hatter is sentenced to death because ‘He’s murdering the time!’ A watch tells the days of the month, not the hours of the day. The Red Queen inverts the normal time sequence by proclaiming, ‘Sentence first, verdict later!’ and the White Queen proclaims, ‘it’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards’. Alice neatly sums up the twin themes of reality and time shifts: ‘It’s no use going back to yesterday, because I was a different person then’.

The manipulation of time is also central to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Grey (1890), which brings together the themes of an alternative reality and of time ‘frozen’ in a painting. JM Barrie’s play Peter Pan (1904) presents a more literal version of time standing still, in the form of the boy who refused to grow up, a setting – significantly called Neverland – in which the passage of time is ambiguously unreal, and a hungry crocodile that swallows a clock whose ‘tick-tock’ transforms it into an ominous embodiment of passing time [78].

At a more subtle level, Ėdouard Dujardin’s Les Lauriers sont Coupés (1888) rejected strict chronology in favour of free association and a form of the ‘stream of consciousness’ allied to Jamesian concepts [79]. Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866) was based on a minute description of the protagonist’s inner thoughts, with a plot that unfolded over a period shorter than the average reader takes to read it – a concept of a ‘present’ that seemed to continue almost indefinitely [80]. Proust’s monumental In Search of Lost Time, published in stages from 1913 onwards, also ignores the constraints of linear time, intermingling a past and a present, with the present continually triggering the past [81]. In Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier (1915), the reader rather than the protagonist, experiences a form of mental time travel as a result of the author’s radical experimentations in a third person narrative sequence by using ‘flashbacks’ and ‘flash forwards’ in time.

Crime, detection and penny dreadfuls

While the connection is less direct, the extraordinary new sense of immediacy also provided fertile ground for the development of the new genre of crime or detective fiction. This genre involved ‘cleverly constructed stories, the whole interest of which consists in the gradual unravelling of some carefully prepared enigma’[82]. The genre is commonly accepted as first emerging in its modern version in the 1840s, with Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue and other short stories, followed by Wilkie Collins’ novels The Woman in White (1859) and The Moonstone (1868) [83].

Detective fiction contained many intriguing aspects for readers. Firstly, it turned the focus of stories from the adventures of daring criminals (such as Dick Turpin) to the discoveries of brilliant detectives -- in the words of one critical commentator, it developed as ‘a literary institutionalisation of the habits of mind of the new police force’[84]. Secondly, the stories were increasingly driven by plot, and the uncovering of detail, often at the expense of character. Thirdly, and most significantly for our purposes, the approach taken by detectives resembled that taken by the groundbreaking geologists or evolutionists – they began with the present, and then methodically travelled back into the past to uncover the reasons why the present is as it is [85].

Detectives thus became the medium for readers to experience a form of time travel. This had the effect of turning the traditional treatment of tragedy on its head – instead of a character’s fatal flaw leading eventually to an unpleasant and usually inevitable end, detective stories usually started with the unpleasant event and, by working backwards in time, eventually reached a fulfilling conclusion. As Raymond Chandler remarked, ‘a detective story is a tragedy with a happy ending’[86]. The dramatic originality of the genre was indicated by the number of words that needed to be coined or redefined in order for the new stories to be told – not just the word ‘detective’ itself, but also words such as clue, sleuth, hunch, lead and red herring.

The rapid growth in the public’s (and writers’) interest in crime had been fuelled largely by the growth of the popular penny press that we have discussed earlier. Crime provided one of the most sensational sources of material for these publications [87] – as one character in Dickens’ Great Expectations (1861) reads the news, he becomes ‘imbued with blood to the eyebrows’[88]. In turn, these crime reports in turn provided attractive plot lines for authors. As Altick points out, ‘every good new Victorian murder helped legitimise and prolong the fashion of sensational plots’[89].

Around the same time, the development of a British national police force and criminal investigation departments [90], together with the instantaneity provided by telegraphic communication, led to a much more professional and rapid approach to detection and enforcement. To a significant extent, detectives were products of the new time-saving technologies. In one sensational murder case, the dramatic changes flowing from this new time-immediacy were described as ‘almost miraculous’, with the Glasgow Herald breathlessly recounting how a description of the suspect had been sent from London ‘at ten minutes before one o’clock’, and ‘a few minutes after one’ the police were at her door. Then ‘before the clock had struck two’, a telegraph was on its way back to London to report her arrest. ‘So magically had all this been effected’ that the police in London had barely returned to Scotland Yard before the news of the arrest was with them [91].

The stark nature of the change is illustrated by contrasting the investigation of an early 19th century robbery, as presented George Eliot’s Silas Marner, with that of a similar crime occurring a few decades later in 1848, as presented in Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone. The earlier investigation simply involved informing a local magistrate and the eventual setting up of a kind of local committee, with both measures proving to be ineffectual. By contrast, in The Moonstone, the crime was reported by the newly-invented telegraph to the newly-developed Scotland Yard, and the police arrived at the crime scene within hours, travelling by the newly-developed railway [92].

This capacity of telegraph messages and trains to play a dramatic role in criminal investigations generated enormous public interest. In 1845, for example, the murderer John Tawell achieved the twin distinction of becoming the first person to be arrested as the result of telecommunications technology and – reportedly – the first murderer to flee the scene of the crime by rail [93]. After being spotted acting suspiciously and catching a train to London, Tawell had been overtaken by a telegraphic message containing his description, and was consequently arrested by a railway policeman soon after his arrival. The drama, not surprisingly, ‘filled the newspapers for months’[94]. Contemporary commentators were prompted to dub the telegraph as ‘the electric constable’[95],or ‘God’s lightning’[96], and the telegraph lines were described as ‘the cords that hung John Tawell’[97]. One newspaper marvelled at how a ‘guilty wretch, flying on the wings of steam’, could be ‘tracked by a swifter messenger’[98].

The consequent emphasis on time fostered the development of many staple components of the modern crime genre – the notion of establishing the exact time of death and the related concept of alibis that could be rigorously tested; a ‘crime scene’ that was effectively frozen so that it could not corrupted by the passage of time or third party interference [99]; the resultant ability of investigators to place reliance on ‘clues’ that could be discovered there; and a chase often reliant on rapid forms of transport. Photography, too, began to play a part. The practice of systematically recording (or "freezing") crime scenes by photography, and taking "mugshots"of criminals, started being adopted in the 1890s, largely pioneered by the work of Alphonse Bertillon in France.

At a practical level, the shorter journey times facilitated by the railways also gave rise to the development of cheap, short, standardised books suitable to be read on the train in one sitting -- a 'literature for the rail' [99].

[End of Pt 2]

Now go to:

Part 3: The 'new' time in painting

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018

We welcome your comments on this article

END NOTES [continued from Pt 1]

73. This term did not become common until the 1920s. At the time of their first appearance, these works were generally described as ‘scientific romances’ or ‘speculative fiction’ (Ousland, I (ed), The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1993 at 834). Some elements of science fiction had of course appeared in earlier stories – typically featuring imaginary voyages – but what generally distinguished the new genre from mere fantasy was that they generally respected the limits of scientific possibility, albeit sometimes elastically interpreted. For other non-English precursors, see Tiphaigne de la Roche's Giphantie (1760), which envisaged a form of photography; and François-Félix Nogaret's Le miroir des événemens actuels, ou La belle au plus offrant, histoire à deux visages (1790).

73a. The 19 year-old Mary Shelley saw her novel as having elements both of supernatural romance and of scientific reflections on the nature of the origins of life: see Muriel Spark: Child of Light: Mary Shelley, Welcome Bain, New York, 2002 at 156.

73b. Written when Loudon was just 20, Loudon's book is "full of totally unexpected technical inventions, such as 'steam percussion bridges', heated streets, mobile homes on rails, smokeless chemical fuels, electric hats... and a full-size balloon made from a nugget of highly concentrated Indiarubber": Richard Holmes, Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air, William Collins, London, 2013 at 51.

74. Washington Irving’s Rip van Winkle (1810) may also be a contender, though it is arguable that this story does not involve time travel, but simply the effects of an abnormally long sleep.

75. For example, A Christmas Carol featured a ghost, Connecticut Yankee a blow to the head, and Rip van Winkle an alcoholic stupor. William Morris' News from Nowhere (1891), Bellamy's Looking Backward, and Boitard's Paris Before Men all involved falling asleep/dreaming. Indeed, there are even isolated works from the eighteenth century which include elements of time travel occurring in a dream-like state: see, for example, Samuel Madden’s Memoirs of the Twentieth Century (1733) and Louis-Sebastien Mercier’s L’an 2440, reve s’il en fut jamais [The year 2440: A year if ever there was one] (1771). The concept of a world travelling backwards can be traced at least back to Plato’s Dialogue Statesman circa 360BCE.

76. See generally Nahin, PJ, Time Machines: Time Travel in Physics, Metaphysics and Science Fiction 2 edn Springer-Verlag, New York, 1999.

77. Williams, K, HG Wells, Modernity and the Movies, Liverpool University Press, Liverpool, 2007 at 8.

78. This is almost a literal manifestation of Ovid’s description of Time as ‘the devourer of all things’ (Metamorphoses, Book 15, l 871).

79. James Joyce would later acknowledge Dujardin as an influence on his own, even more ambitious, work Ulysses (1922).

80. His novella Notes from Underground (1864) also employed techniques related to stream of consciousness.

81. Another early example was Ambrose Bierce’s Occurrence at Owl Creek (1893), which takes place entirely in the moment from when a man is dropped off the gallows until the instant he dies (Shlain at 299). In a very general sense, too, the development of a long-term time perspective during the nineteenth century became reflected in, and reinforced by, a burgeoning interest in historical novels and biographies

82. Brantlinger, P, ‘What is sensational about the sensation novel?’, Nineteenth Century Fiction vol 37, No 1 Jun 1982 1-28 at 3, quoting article ‘The Enigma Novel’, The Spectator, 28 December 1861. There are interesting precursors of the genre in the 18th century contemporaneous accounts of actual crimes, such as Samuel Foote's The Genuine Account of the Murder of Sir John Dinely Goodere (1742): see Ian Kelly, Mr Foote's Other Leg, Picador, London 2012.

83. Inspector Bucket in Dickens’ Bleak House (1852/3), although a relatively minor character, was also an important early influence. The Notting Hill Mystery (1862/5) by "Charles Felix" (Charles Warren Adams) was also an early example. One should also not overlook the influence of the larger-than-life French criminal/policeman, Eugène Vidocq, who founded the Sûreté, published best-selling Memoirs in 1828, and whose chequered career evidently was the basis for many later fictional characters, most notably both of the protagonists in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. Vidocq was also referred to in Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue. See generally James Morton, The First Detective, Ebury Press, London 2006.

84. Summerscale, K, The Suspicions of Mr Whicher, Bloomsbury, London, 2008, at 111, at 222 and at 300 n 55.

85. In 1906, Freud also likened the task of the detective to that of the psychoanalyst (Summerscale, op cit at 103). This type of approach was also evident in the growth of historical novels in the nineteenth century.

86. Summerscale, op cit, at 304.

87. The first edition of the grandly-titled News of the World in 1843 was typical – it led with a classic Victorian sensation, the lurid tale of a female chemist raped and thrown into the Thames.

88. Summerscale, op cit, at 106.

89. Brantlinger, op cit, at 9, quoting Altick, R, in Victorian Studies in Scarlet (NY, Norton 1970 at 79).Wilkie Collins for example, evidently based stories partly on news reports of the Road Hill murder in 1860 and the Northumberland Street murder in 1861. While this practice added to the reality and credibility of plots, it also became the basis for criticism that the new genre lacked originality. Elements of the Road Hill murder also appear in Dickens’ unfinished The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870). For an excellent modern account of the Road Hill murder, see Summerscale, op cit.

90. In England, the Metropolitan Police of London was established in 1829 and a dedicated detective branch in 1842. For a review of early fiction featuring detectives (both police and private), see Shpayer-Makov, H, ‘Revisiting the Detective in Late Victorian and Edwardian Fiction – A View from the Perspective of Police History’, Law, Crime and History (2011) 2. Charles Dickens was fascinated with the novel phenomenon: see ‘A Detective Police Party’, Household Words, 27 July 1850

91. Flanders, J, The Invention of Murder, HarperPress,. London 2011 at 161, quoting the Glasgow Herald, 27 August 1849. The case was dubbed the ‘Bermondsey Horror’ and the suspect, Maria Manning, was later hanged. Dickens, who attended Manning’s public execution, is believed to have based the a character in Bleak House on her.

92. Sutherland, op cit, at xxiii.

93. For further details of Tawell's remarkable life and death, see Prussian blue and its partner in crime.The first reported murder to take place on board a train in Britain did not occur until 1864, though theft was very common (Website of British Transit Police http://www.btp.police.uk/ ; Colquhoun, K, Mr Briggs' Hat: A Sensational Account of Britain's First Railway Murder, Little, Brown, London 2011). An earlier railway murder took place in France in 1860 (Colquhoun, at 45).

94. Gleick (Information), op cit, at 144; Miller, G, ‘Famous murderer caught by the wire’, The Pharmaceutical Journal 21 December 2002, cited in Website of British Transit Police http://www.btp.police.uk/ . For an account of Tawell’s chequered career in both England and Australia, see Buckland, J, Mort’s Cottage 1838-1988, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 1988 at 9–39; the detailed treatment in Carol Baxter, The Peculiar Case of the Electric Constable, Oneworld Publications, London, 2013; and our article Prussian blue and its partner in crime.

95. Wynter, A, ‘The Electric Telegraph’, Quarterly Review, June 1854, 118 at 129.

96. Flanders, J, op cit at 161, quoting Punch magazine.

97. This doleful comment by a railway passenger, breaking the customary silence of an English railway carriage, was recorded by Sir Francis Head in Stokers and Pokers (1849), quoted in Fraser, M, The Rise of Slough, Slough Corporation, at 52. On the other hand, of course, the increased mobility could also be a boon for criminals too. The Times of 17 January 1857 "lectured its readers on the manner in which professional burglars were travelling by railway, often in first-class carriages, moving from town to town with a speed that the police could scarcely match": Donald Thomas, The Victorian Underworld, John Murray, London, 1998 at 2.

98. Flanders, op cit at 161, quoting the Illustrated London News, 1 September 1849, p 147. Telegrams also played a significant role in the apprehension of Abraham Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth in 1865. A wireless telegram also played a pivotal role in the transatlantic arrest of the notorious ‘cellar murderer’ Dr Crippen in 1910, a case that excited worldwide interest at the time, and continues to resound even today. Crippen’s crime inspired numerous ‘true life’ books, novels, plays, musicals, films, television programs and a Madame Tussaud waxwork. Even as late as 2007, however, it was being reported that newly discovered DNA evidence supposedly cast doubt on Crippen’s guilt (Hodgson, M, ‘100 years on, DNA casts doubt on Crippen case’, The Guardian, 17 October 2007

99. Clark Blaise, The Time Lord: Sir Sandford Fleming and the Creation of Standard Time, Weidenfield & Nicholson, London 2009 at 139.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015

Citation: Philip McCouat, "Art in a Speeded up World", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home

At a practical level, the shorter journey times facilitated by the railways also gave rise to the development of cheap, short, standardised books suitable to be read on the train in one sitting -- a 'literature for the rail' [99].

[End of Pt 2]

Now go to:

Part 3: The 'new' time in painting

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018

We welcome your comments on this article

END NOTES [continued from Pt 1]

73. This term did not become common until the 1920s. At the time of their first appearance, these works were generally described as ‘scientific romances’ or ‘speculative fiction’ (Ousland, I (ed), The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1993 at 834). Some elements of science fiction had of course appeared in earlier stories – typically featuring imaginary voyages – but what generally distinguished the new genre from mere fantasy was that they generally respected the limits of scientific possibility, albeit sometimes elastically interpreted. For other non-English precursors, see Tiphaigne de la Roche's Giphantie (1760), which envisaged a form of photography; and François-Félix Nogaret's Le miroir des événemens actuels, ou La belle au plus offrant, histoire à deux visages (1790).

73a. The 19 year-old Mary Shelley saw her novel as having elements both of supernatural romance and of scientific reflections on the nature of the origins of life: see Muriel Spark: Child of Light: Mary Shelley, Welcome Bain, New York, 2002 at 156.

73b. Written when Loudon was just 20, Loudon's book is "full of totally unexpected technical inventions, such as 'steam percussion bridges', heated streets, mobile homes on rails, smokeless chemical fuels, electric hats... and a full-size balloon made from a nugget of highly concentrated Indiarubber": Richard Holmes, Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air, William Collins, London, 2013 at 51.

74. Washington Irving’s Rip van Winkle (1810) may also be a contender, though it is arguable that this story does not involve time travel, but simply the effects of an abnormally long sleep.

75. For example, A Christmas Carol featured a ghost, Connecticut Yankee a blow to the head, and Rip van Winkle an alcoholic stupor. William Morris' News from Nowhere (1891), Bellamy's Looking Backward, and Boitard's Paris Before Men all involved falling asleep/dreaming. Indeed, there are even isolated works from the eighteenth century which include elements of time travel occurring in a dream-like state: see, for example, Samuel Madden’s Memoirs of the Twentieth Century (1733) and Louis-Sebastien Mercier’s L’an 2440, reve s’il en fut jamais [The year 2440: A year if ever there was one] (1771). The concept of a world travelling backwards can be traced at least back to Plato’s Dialogue Statesman circa 360BCE.

76. See generally Nahin, PJ, Time Machines: Time Travel in Physics, Metaphysics and Science Fiction 2 edn Springer-Verlag, New York, 1999.

77. Williams, K, HG Wells, Modernity and the Movies, Liverpool University Press, Liverpool, 2007 at 8.

78. This is almost a literal manifestation of Ovid’s description of Time as ‘the devourer of all things’ (Metamorphoses, Book 15, l 871).

79. James Joyce would later acknowledge Dujardin as an influence on his own, even more ambitious, work Ulysses (1922).

80. His novella Notes from Underground (1864) also employed techniques related to stream of consciousness.

81. Another early example was Ambrose Bierce’s Occurrence at Owl Creek (1893), which takes place entirely in the moment from when a man is dropped off the gallows until the instant he dies (Shlain at 299). In a very general sense, too, the development of a long-term time perspective during the nineteenth century became reflected in, and reinforced by, a burgeoning interest in historical novels and biographies

82. Brantlinger, P, ‘What is sensational about the sensation novel?’, Nineteenth Century Fiction vol 37, No 1 Jun 1982 1-28 at 3, quoting article ‘The Enigma Novel’, The Spectator, 28 December 1861. There are interesting precursors of the genre in the 18th century contemporaneous accounts of actual crimes, such as Samuel Foote's The Genuine Account of the Murder of Sir John Dinely Goodere (1742): see Ian Kelly, Mr Foote's Other Leg, Picador, London 2012.

83. Inspector Bucket in Dickens’ Bleak House (1852/3), although a relatively minor character, was also an important early influence. The Notting Hill Mystery (1862/5) by "Charles Felix" (Charles Warren Adams) was also an early example. One should also not overlook the influence of the larger-than-life French criminal/policeman, Eugène Vidocq, who founded the Sûreté, published best-selling Memoirs in 1828, and whose chequered career evidently was the basis for many later fictional characters, most notably both of the protagonists in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. Vidocq was also referred to in Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue. See generally James Morton, The First Detective, Ebury Press, London 2006.

84. Summerscale, K, The Suspicions of Mr Whicher, Bloomsbury, London, 2008, at 111, at 222 and at 300 n 55.

85. In 1906, Freud also likened the task of the detective to that of the psychoanalyst (Summerscale, op cit at 103). This type of approach was also evident in the growth of historical novels in the nineteenth century.

86. Summerscale, op cit, at 304.

87. The first edition of the grandly-titled News of the World in 1843 was typical – it led with a classic Victorian sensation, the lurid tale of a female chemist raped and thrown into the Thames.

88. Summerscale, op cit, at 106.

89. Brantlinger, op cit, at 9, quoting Altick, R, in Victorian Studies in Scarlet (NY, Norton 1970 at 79).Wilkie Collins for example, evidently based stories partly on news reports of the Road Hill murder in 1860 and the Northumberland Street murder in 1861. While this practice added to the reality and credibility of plots, it also became the basis for criticism that the new genre lacked originality. Elements of the Road Hill murder also appear in Dickens’ unfinished The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870). For an excellent modern account of the Road Hill murder, see Summerscale, op cit.

90. In England, the Metropolitan Police of London was established in 1829 and a dedicated detective branch in 1842. For a review of early fiction featuring detectives (both police and private), see Shpayer-Makov, H, ‘Revisiting the Detective in Late Victorian and Edwardian Fiction – A View from the Perspective of Police History’, Law, Crime and History (2011) 2. Charles Dickens was fascinated with the novel phenomenon: see ‘A Detective Police Party’, Household Words, 27 July 1850

91. Flanders, J, The Invention of Murder, HarperPress,. London 2011 at 161, quoting the Glasgow Herald, 27 August 1849. The case was dubbed the ‘Bermondsey Horror’ and the suspect, Maria Manning, was later hanged. Dickens, who attended Manning’s public execution, is believed to have based the a character in Bleak House on her.

92. Sutherland, op cit, at xxiii.

93. For further details of Tawell's remarkable life and death, see Prussian blue and its partner in crime.The first reported murder to take place on board a train in Britain did not occur until 1864, though theft was very common (Website of British Transit Police http://www.btp.police.uk/ ; Colquhoun, K, Mr Briggs' Hat: A Sensational Account of Britain's First Railway Murder, Little, Brown, London 2011). An earlier railway murder took place in France in 1860 (Colquhoun, at 45).

94. Gleick (Information), op cit, at 144; Miller, G, ‘Famous murderer caught by the wire’, The Pharmaceutical Journal 21 December 2002, cited in Website of British Transit Police http://www.btp.police.uk/ . For an account of Tawell’s chequered career in both England and Australia, see Buckland, J, Mort’s Cottage 1838-1988, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 1988 at 9–39; the detailed treatment in Carol Baxter, The Peculiar Case of the Electric Constable, Oneworld Publications, London, 2013; and our article Prussian blue and its partner in crime.

95. Wynter, A, ‘The Electric Telegraph’, Quarterly Review, June 1854, 118 at 129.

96. Flanders, J, op cit at 161, quoting Punch magazine.

97. This doleful comment by a railway passenger, breaking the customary silence of an English railway carriage, was recorded by Sir Francis Head in Stokers and Pokers (1849), quoted in Fraser, M, The Rise of Slough, Slough Corporation, at 52. On the other hand, of course, the increased mobility could also be a boon for criminals too. The Times of 17 January 1857 "lectured its readers on the manner in which professional burglars were travelling by railway, often in first-class carriages, moving from town to town with a speed that the police could scarcely match": Donald Thomas, The Victorian Underworld, John Murray, London, 1998 at 2.

98. Flanders, op cit at 161, quoting the Illustrated London News, 1 September 1849, p 147. Telegrams also played a significant role in the apprehension of Abraham Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth in 1865. A wireless telegram also played a pivotal role in the transatlantic arrest of the notorious ‘cellar murderer’ Dr Crippen in 1910, a case that excited worldwide interest at the time, and continues to resound even today. Crippen’s crime inspired numerous ‘true life’ books, novels, plays, musicals, films, television programs and a Madame Tussaud waxwork. Even as late as 2007, however, it was being reported that newly discovered DNA evidence supposedly cast doubt on Crippen’s guilt (Hodgson, M, ‘100 years on, DNA casts doubt on Crippen case’, The Guardian, 17 October 2007

99. Clark Blaise, The Time Lord: Sir Sandford Fleming and the Creation of Standard Time, Weidenfield & Nicholson, London 2009 at 139.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015

Citation: Philip McCouat, "Art in a Speeded up World", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home