The origins of an australian art icon

charles Meere's Australian beach Pattern

By Philip McCouat For reader comments on this article see here

During the 20th century, the beach started to rival the outback as one of the defining symbols of Australian life. The beach represented a casual freedom, fun, the outdoors and healthy sport – and it was open to all. In the interwar, post-Depression period of the 1930s, Australian artists increasingly turned to it for inspiration.

Among these artists was Charles Meere, who had settled in Sydney as a mature artist in 1932/33, after living and studying art in his native England and in France, and serving in the First World War [1]. While pursuing his Sydney art practice, he also worked as a commercial artist, exhibited widely and taught life-classes at East Sydney Technical College. He achieved considerable artistic and commercial success, winning the Sulman Prize in 1938 with Atalanta’s Eclipse, a neo-classical interpretation of the Greek myth [2]. One of his colleagues described him as "somewhat of a character, slightly eccentric, looking like a businessman, with a droll sense of humour" [2a].

Meere’s most famous work, Australian Beach Pattern, again uses classically-posed and rather heroic figures, but positions them in a novel – and outwardly incongruous – beach setting (Fig 1). Conceived and executed over the period 1938 to 1940, this work has achieved a quasi-iconic status in Australia [3], becoming one of the most popular paintings in the Art Gallery of NSW [4], appearing on book covers [5] and, as we shall later see, inspiring various other artists. It was among the quintessential Australian images chosen for the 2000 Olympics Opening Ceremony Program [6] and was included in the major exhibition of Australian Art held at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in late 2013.

During the 20th century, the beach started to rival the outback as one of the defining symbols of Australian life. The beach represented a casual freedom, fun, the outdoors and healthy sport – and it was open to all. In the interwar, post-Depression period of the 1930s, Australian artists increasingly turned to it for inspiration.

Among these artists was Charles Meere, who had settled in Sydney as a mature artist in 1932/33, after living and studying art in his native England and in France, and serving in the First World War [1]. While pursuing his Sydney art practice, he also worked as a commercial artist, exhibited widely and taught life-classes at East Sydney Technical College. He achieved considerable artistic and commercial success, winning the Sulman Prize in 1938 with Atalanta’s Eclipse, a neo-classical interpretation of the Greek myth [2]. One of his colleagues described him as "somewhat of a character, slightly eccentric, looking like a businessman, with a droll sense of humour" [2a].

Meere’s most famous work, Australian Beach Pattern, again uses classically-posed and rather heroic figures, but positions them in a novel – and outwardly incongruous – beach setting (Fig 1). Conceived and executed over the period 1938 to 1940, this work has achieved a quasi-iconic status in Australia [3], becoming one of the most popular paintings in the Art Gallery of NSW [4], appearing on book covers [5] and, as we shall later see, inspiring various other artists. It was among the quintessential Australian images chosen for the 2000 Olympics Opening Ceremony Program [6] and was included in the major exhibition of Australian Art held at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in late 2013.

This painting, with its mixture of the strange and the familiar, has inspired a number of competing interpretations, ranging from the innocent to the frankly sinister [6A]. In this article, we examine some of these interpretations – and their possible drawbacks – and suggest that there may be additional ways in which this painting can be understood.

A warm celebration of beach culture?

Meere’s work can be approached on a number of levels. On its face, it simply depicts an action-packed family day at the beach, an activity that had become increasingly popular during the interwar period. If you venture a little further, you might say – along with countless others – that it is a “celebration” of the Australian beach culture, influenced by the 1930s trend to mythologise the Australian way of life.

It seems odd that Meere, so classically trained and not exactly an outdoors type, would be particularly enamoured with beach life. According to his close associate and student Freda Robertshaw, “Charles never went to the beach. We made up most of the figures, occasionally using one of Charles’ employees as a model for the hands and feet but never using the complete figure”[7]. If this is so, the description of Pattern as a celebration is probably more a reflection of how the painting has been perceived by its viewers, not necessarily what Meere was intending [8].

It seems odd that Meere, so classically trained and not exactly an outdoors type, would be particularly enamoured with beach life. According to his close associate and student Freda Robertshaw, “Charles never went to the beach. We made up most of the figures, occasionally using one of Charles’ employees as a model for the hands and feet but never using the complete figure”[7]. If this is so, the description of Pattern as a celebration is probably more a reflection of how the painting has been perceived by its viewers, not necessarily what Meere was intending [8].

A cold celebration of heroic racial purity?

Early critical commentary on the painting struggled with its unfamiliar combination of formality and the casual fun normally experienced at an Australian beach. These critics expressed stern disapproval of what they perceived as an artificial, unfeeling, cold formality. This led to the painting being described with words such as dull, laborious, literal, lacking in lyric feeling, prosaic, frigid, inhuman, lifeless and academic [9]. Despite the rather overwrought nature of these criticisms, it is unlikely that Meere would have been too surprised by this. After all, he titled his work Australian Beach Pattern, not Happy Day at the Seaside. Meere spent over two years on composing the image, going to infinite pains to ensure that it was exactly as he wished, and his interest in form and structure had already been evident in his previous works. His work may have been unfashionable in some critical circles, but it does not appear that this was Meere’s concern.

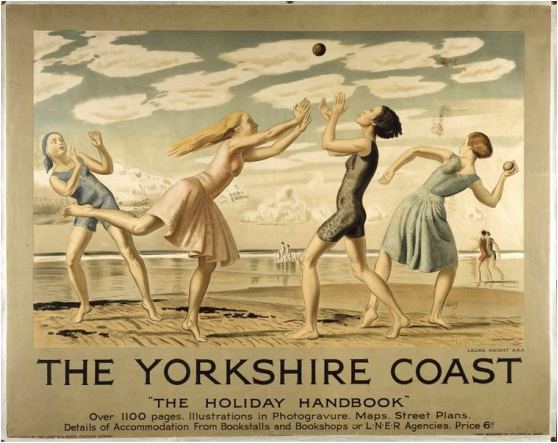

More seriously, some later critics advanced a now often-held view that the work depicts and even intentionally glorifies notions of racial purity. They suggested that there were affinities between Pattern and the ideals of health and heroism that were prominent in Nazi Germany during the 1930s, where classical idealism was associated with images of “modern Aryans”. So, for example, Pattern has been described as an “iconic example of ‘Aryan’ hedonism in Australian life”[10], “a political statement about the ideal Australian race”[11], and a “sun-soaked eugenic argument" [12] with figures that have something "almost fascistic" about them [12A]. Among other comments collected by Joy Eadie, the painting supposedly “eulogises national identity”, the figures are “embodiments of eugenic and racial goals” and are “perfect in body and morally sanctified”. One commentator has even likened Pattern to totalitarian art [13]. it would be interesting to see if such criticisms would also be levelled at Dame Laura Knight's 1929 poster, The Yorkshire Coast, with which Meere's painting has significant stylistic affinities (Fig 1A).

More seriously, some later critics advanced a now often-held view that the work depicts and even intentionally glorifies notions of racial purity. They suggested that there were affinities between Pattern and the ideals of health and heroism that were prominent in Nazi Germany during the 1930s, where classical idealism was associated with images of “modern Aryans”. So, for example, Pattern has been described as an “iconic example of ‘Aryan’ hedonism in Australian life”[10], “a political statement about the ideal Australian race”[11], and a “sun-soaked eugenic argument" [12] with figures that have something "almost fascistic" about them [12A]. Among other comments collected by Joy Eadie, the painting supposedly “eulogises national identity”, the figures are “embodiments of eugenic and racial goals” and are “perfect in body and morally sanctified”. One commentator has even likened Pattern to totalitarian art [13]. it would be interesting to see if such criticisms would also be levelled at Dame Laura Knight's 1929 poster, The Yorkshire Coast, with which Meere's painting has significant stylistic affinities (Fig 1A).

It may be a stretch to describe Pattern as some kind of celebration of racial purity unless there is some objective evidence that this really represented Meere’s view. However, in some cases, commentators have come to regard it as almost self-evident, on the basis of a face-value reading of the painting and the fact that the painting appeared during a period when these thoughts were current in Germany. Of course, those commentators might possibly be right, but precisely why Meere would necessarily sympathise with German eugenic or racial views is not clear. He had served in France against Germany in the horrors of the First World War, and at the very time the painting appeared both his native and adopted countries were yet again engaged in bitter fighting against that country. In these circumstances, as Eadie comments, it was hardly self-evident why Meere would choose to “endorse the artistic or political vision of the Third Reich”[14].

A similar objection may apply to unsupported assertions that Pattern was inspired by, and reflected, the rampant nationalism that swept parts of Australia as a result of its 1938 Sesquicentenary celebrations. Not every Australian viewed those celebrations with unbridled enthusiasm. Indeed, in some artistic circles, the excesses of the Sesquicentenary were openly mocked [15]. As Eadie has commented, it would be surprising if a person who had spent much of his life in England and France would be so impressed with a 150th anniversary (wow!) that he would be moved to “spend a year of his life painting a celebration of Australians as the epitome of racial perfection”[16].

Some 50 years after Pattern appeared, some echoes of this type of interpretation resurfaced with Anna Zahalka’s photographic parody The bathers (1989) (Fig 2). Her work highlights the gap between reality and myth by the use of photography – traditionally regarded as revealing the “real” position – coupled with the obvious staginess of the work. With an artificial backdrop of the sea, this highly-coloured work depicts a group of people in poses clearly reminiscent of Pattern, but with a droll twist. Instead of heroic poses, the characters stand about looking rather awkward and self-conscious. Instead of the preponderance of males, the sexes are more evenly balanced, and the woman holding the beach ball has been made more central [17]. Instead of the toned, fit bodies shown in Pattern, there are some more “ordinary” looking people. And, perhaps most importantly, instead of the Anglo emphasis of Pattern, there is an emphasis on people of non-Anglo origin occupying the foreground.

A similar objection may apply to unsupported assertions that Pattern was inspired by, and reflected, the rampant nationalism that swept parts of Australia as a result of its 1938 Sesquicentenary celebrations. Not every Australian viewed those celebrations with unbridled enthusiasm. Indeed, in some artistic circles, the excesses of the Sesquicentenary were openly mocked [15]. As Eadie has commented, it would be surprising if a person who had spent much of his life in England and France would be so impressed with a 150th anniversary (wow!) that he would be moved to “spend a year of his life painting a celebration of Australians as the epitome of racial perfection”[16].

Some 50 years after Pattern appeared, some echoes of this type of interpretation resurfaced with Anna Zahalka’s photographic parody The bathers (1989) (Fig 2). Her work highlights the gap between reality and myth by the use of photography – traditionally regarded as revealing the “real” position – coupled with the obvious staginess of the work. With an artificial backdrop of the sea, this highly-coloured work depicts a group of people in poses clearly reminiscent of Pattern, but with a droll twist. Instead of heroic poses, the characters stand about looking rather awkward and self-conscious. Instead of the preponderance of males, the sexes are more evenly balanced, and the woman holding the beach ball has been made more central [17]. Instead of the toned, fit bodies shown in Pattern, there are some more “ordinary” looking people. And, perhaps most importantly, instead of the Anglo emphasis of Pattern, there is an emphasis on people of non-Anglo origin occupying the foreground.

Zahalka’s work therefore can be seen as updating Meere’s subject matter to reflect more closely the demographic mix of Australia in the late 1980s. As Anne O’Hehir has pointed out, however, Zahalka “has replaced one stereotype of Australia with another. She can give us a more accurate image of our time but she cannot ultimately step out of history to gives us individuals instead of stereotypes. The people. .. can only be read as representatives of types”[18].

In addition to being a more modern updating of the ethnic mix, some have suggested that Zahalka’s work can also be seen as suggesting that Pattern presented a false view of Australia even back in the 1940s. If so, however, such an interpretation may need some refinement. Meere’s work was probably a fairly accurate view of the racial mix (or rather non-mix) of people likely to be seen on Australian beaches in 1940. At that time, Australia was practising the so-called “White Australia” policy, and the era of mass migration from continental Europe, let alone Asia, was still years away. Even by 1947, less than 10% of the Australian population were born overseas and, of those, almost three-quarters were from Great Britain and Ireland [19]. It can therefore be argued that, so far as the racial mix in 1940 is concerned, Meere was to a significant extent simply reflecting what he saw.

Of course, Zahalka’s work also can be seen as a dig at the perceived heroics of Pattern. Meere clearly idealised the smooth physiques of his figures to some degree, even bearing in mind the uncomfortable fact that Australians generally looked rather fitter in 1940 than many of them do today. However, even this criticism loses some force if Meere himself was using his classical bodies not as ideals, but for ironic effect in order to give effect to some more subtle message. It is to this possibility that we now turn.

In addition to being a more modern updating of the ethnic mix, some have suggested that Zahalka’s work can also be seen as suggesting that Pattern presented a false view of Australia even back in the 1940s. If so, however, such an interpretation may need some refinement. Meere’s work was probably a fairly accurate view of the racial mix (or rather non-mix) of people likely to be seen on Australian beaches in 1940. At that time, Australia was practising the so-called “White Australia” policy, and the era of mass migration from continental Europe, let alone Asia, was still years away. Even by 1947, less than 10% of the Australian population were born overseas and, of those, almost three-quarters were from Great Britain and Ireland [19]. It can therefore be argued that, so far as the racial mix in 1940 is concerned, Meere was to a significant extent simply reflecting what he saw.

Of course, Zahalka’s work also can be seen as a dig at the perceived heroics of Pattern. Meere clearly idealised the smooth physiques of his figures to some degree, even bearing in mind the uncomfortable fact that Australians generally looked rather fitter in 1940 than many of them do today. However, even this criticism loses some force if Meere himself was using his classical bodies not as ideals, but for ironic effect in order to give effect to some more subtle message. It is to this possibility that we now turn.

A wake-up call for war?

In recent years, there have emerged some nuanced interpretations of what Pattern is about. Linda Slutzkin has hinted at its possible connection with war, noting how “this strenuous composition with its heroic figures is more suggestive of a Renaissance battle scene”, and memorably describing the figures as “Spartans in Speedos”[20]. Joy Eadie has elaborated on this possible war connection, arguing that previous critics have taken the painting too literally and at face value, ignoring “such artistic devices as allusion, ambiguity, and irony”[21].

Eadie argues that the painting actually reflected two war-related themes. The first was essentially political – Australia’s unpreparedness for war. As support for this theme, she draws on various compositional elements common to both Pattern and to Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819), such as the overlapping triangles of figures, and other specific similarities, such as the child waving his spade mirroring the Raft’s child signalling for help [22]. Noting that the Raft was widely interpreted as “an indictment of the negligent rulers of the French ship of state, abandoning the people to their fate”, Eadie goes on to say that perhaps Pattern similarly “suggests that the Australian people at play on the beach were vulnerable, adrift, like the outcasts from the Medusa, ill-served by their leaders. The shaken towel, a white flag, symbol of surrender, flies at the centre. The signposts are blank, the sandcastles are about to be washed away, the only ship in sight is a toy. Were these lovely people with their young helplessly and unwittingly awaiting the slaughter of Australia at play while the world burned?”[23].

The second theme, according to Eadie, is the more personal looming sacrifice of Australia’s young men in the world-wide conflict. In support of this, Eadie points to the “Madonna and Child” group of figures in the left foreground, stating that they represent Meere’s own family – the artist (standing alone in the left background), his wife, their daughter and infant son. Significantly, she suggests that, in accordance with European iconography, the red ball for which the son is reaching out represents the Biblical forbidden fruit, and symbolises Christ’s future sacrificial role in redemption from original sin through his crucifixion [24]. This round red shape is a recurring motif in the painting, appearing in the red cap of the deckchair-seated woman, the open red bucket held by the nearby naked child, again appearing in the bucket in the lower left foreground, and in the round sign in the background. Eadie concludes that the painting depicts the successive stages in the life of a male from infancy to manhood, suggesting that the boys from the infant up are marked out for sacrifice, born to repeat the same pattern as Meere and his generation had experienced in the previous war.

Eadie’s intriguing suggestions, while closely argued, are of course speculative, and the question of their validity remains open. However, it may be argued that they gain some additional support from two quite differing sources.

Eadie argues that the painting actually reflected two war-related themes. The first was essentially political – Australia’s unpreparedness for war. As support for this theme, she draws on various compositional elements common to both Pattern and to Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819), such as the overlapping triangles of figures, and other specific similarities, such as the child waving his spade mirroring the Raft’s child signalling for help [22]. Noting that the Raft was widely interpreted as “an indictment of the negligent rulers of the French ship of state, abandoning the people to their fate”, Eadie goes on to say that perhaps Pattern similarly “suggests that the Australian people at play on the beach were vulnerable, adrift, like the outcasts from the Medusa, ill-served by their leaders. The shaken towel, a white flag, symbol of surrender, flies at the centre. The signposts are blank, the sandcastles are about to be washed away, the only ship in sight is a toy. Were these lovely people with their young helplessly and unwittingly awaiting the slaughter of Australia at play while the world burned?”[23].

The second theme, according to Eadie, is the more personal looming sacrifice of Australia’s young men in the world-wide conflict. In support of this, Eadie points to the “Madonna and Child” group of figures in the left foreground, stating that they represent Meere’s own family – the artist (standing alone in the left background), his wife, their daughter and infant son. Significantly, she suggests that, in accordance with European iconography, the red ball for which the son is reaching out represents the Biblical forbidden fruit, and symbolises Christ’s future sacrificial role in redemption from original sin through his crucifixion [24]. This round red shape is a recurring motif in the painting, appearing in the red cap of the deckchair-seated woman, the open red bucket held by the nearby naked child, again appearing in the bucket in the lower left foreground, and in the round sign in the background. Eadie concludes that the painting depicts the successive stages in the life of a male from infancy to manhood, suggesting that the boys from the infant up are marked out for sacrifice, born to repeat the same pattern as Meere and his generation had experienced in the previous war.

Eadie’s intriguing suggestions, while closely argued, are of course speculative, and the question of their validity remains open. However, it may be argued that they gain some additional support from two quite differing sources.

Sacrifice and personal loss

For the first, sacrificial, theme, we can consider a painting done, later in 1940, by Meere’s own apprentice/student Freda Robertshaw. She had worked closely with Meere during the conception and execution of Pattern. Her own work Australian Beach Scene (Fig 3) was done while still under his tutelage and, presumably, with his approval [25]. While it is clearly inspired and influenced by Pattern, it presents a more intimate “feminised” version – the group is smaller, the painting is more tightly focused, the gender balance has been reversed so that women predominate, the actions are a little freer. The sign, blank and uninformed in Pattern, is now clearly a cautionary, motherly warning about bathing between the flags.

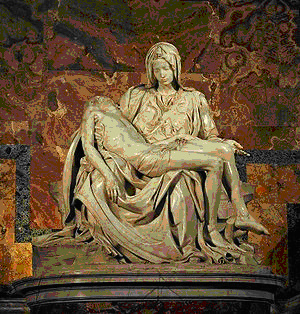

There is, however, one element in this painting that gives further pause for thought – the mother at left is no longer lovingly restraining her lively child as in Pattern, but appears forlorn, with the child lying lifelessly across her lap. It is almost as if the Madonna and Child of the Pattern has somehow been transformed into a Pietà-like depiction of the Madonna holding her dead son (Fig 4).

If we accept that the original group was indeed based on the Meere family, Robertshaw’s work may therefore be a sobering reflection of the fact that the Meere’s infant son in fact died in late 1939, shortly before Pattern was exhibited. The possibility therefore emerges that Australian Beach Scene is not just a feminisation of Pattern - in some ways, although executed more or less contemporaneously with Meere's painting, it may actually act as an update or sequel to it, reflecting the situation as fighting intensified. This would reinforce Eadie’s theme of loss and sacrifice – the Meeres’ loss of their son, and also the disappearance of so many of the men from the scene, who by now have been sent off to war to face their own possible sacrifice.

Unpreparedness and The Battle of Cascina

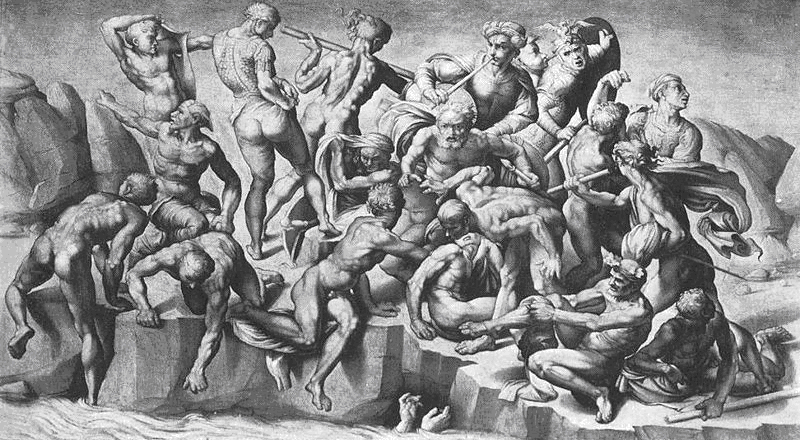

The other possible supporting evidence for Eadie’s interpretation concerns her second theme, that of unpreparedness for war. We have previously mentioned Slutzkin’s suggestion that Pattern was reminiscent of a Renaissance battle scene. If we were searching for a likely candidate for this role, I would suggest Michelangelo’s The Battle of Cascina – significantly, also known as Bathers [26].

Michelangelo was commissioned to execute this work to celebrate the Florentine victory over the Pisans in the 1364 Battle of Cascina. It was intended as a companion fresco to Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari, with the two works decorating opposite walls in the Great Council Hall of the Palazzo della Signoria. As it happened, however, neither work has survived, Leonardo’s because he abandoned his paining due to technical problems, and Michelangelo’s because he never finished it, leaving (like Leonardo) only a detailed cartoon and some working drawings. Today, we know of this work of Michelangelo’s principally through a copy of the cartoon of it executed by his pupil Aristotile da Sangallo (Fig 5) [27].

Michelangelo was commissioned to execute this work to celebrate the Florentine victory over the Pisans in the 1364 Battle of Cascina. It was intended as a companion fresco to Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari, with the two works decorating opposite walls in the Great Council Hall of the Palazzo della Signoria. As it happened, however, neither work has survived, Leonardo’s because he abandoned his paining due to technical problems, and Michelangelo’s because he never finished it, leaving (like Leonardo) only a detailed cartoon and some working drawings. Today, we know of this work of Michelangelo’s principally through a copy of the cartoon of it executed by his pupil Aristotile da Sangallo (Fig 5) [27].

The painting depicts a rather bizarre scene of Florentine soldiers who, instead of preparing for the fighting, have been bathing naked at a stream to gain relief from the heat of the day. They have been taken by surprise by a Pisan attack, and struggle in a confused, contorted, writhing melee to clothe and arm themselves. The painting has memorably been described as “one of the few episodes in medieval warfare that involved mass male nudity”[28]. In contrast to Leonardo’s work, which depicted the horrors of war, Michelangelo’s depiction is more like an idealised exercise in muscled athleticism. It has been commented that the intermingled figures resemble a variety of artistic poses, “a conglomerate of isolated figure studies that has more to say about the history of representation than the city’s glorious military past”[29].

It is tempting to suggest that this work, with its unusual conjunction of war and bathing, may have been in Meere’s mind when he was conceiving Pattern. Certainly, with his longtime interest in murals, it would have been natural for Meere to turn to frescoes for inspiration, just as Michelangelo himself was inspired by classical reliefs and statues from ancient Rome [30]. Both artists’ works also share other elements – the emphasis on classical, healthy, naked (or near naked) figures, the concentration on highly-posed, somewhat artificial postures, an obsession with form and the depiction of a large number of figures in an extraordinarily complex tableau.

Both works also depict the scene as if the artist was standing in the water looking back at the shore. Both depict limbs trailing in the water. The figure in Battle holding a spear is reflected, reversed, by the man in Pattern holding the surfboard; and the upward-facing crook-armed figure at the far right on Battle recalls the woman with the beach ball in Pattern.

A further odd coincidence lies in the important role that cartoons have played in both paintings. Before Michelangelo’s Battle, cartoons had been considered simply as preparatory media, to be discarded or, at best, kept for future projects in the workshop the moment the painting was done [31]. However, it appears that Michelangelo always intended that his Battle cartoon should also have a life in itself as a self-sufficient work of art, irrespective of whether the “real” painting was ever completed. As such, it attracted great admiration from its contemporaries. Vasari noted how Michelangelo’s desire to show off his skills resulted in an extraordinary variety of extravagant poses which left other artists “seized with admiration and astonishment”, and that some, “after beholding figures so divine”, even declared “that there has never been seen any work… that can equal it in divine beauty of art”[32]. Michelangelo’s cartoon therefore acted as a “a school for craftsmen” and a monument to the importance of drawing [33].

Like Michelangelo, Meere also produced an elaborate cartoon for Pattern which he regarded as a self-sufficient work of art. He actually exhibited the cartoon at the Society of Artists 1939 Annual Exhibition, indicating not only the importance the project had for him [34], but also the significance that he attached to the cartoon itself.

It may also be that the educative role of Michelangelo’s work would have appealed to Meere, generally in his role as an art teacher and more specifically if he was using Pattern as a teaching piece for Freda Robertshaw. Finally, if Eadie is correct is saying that Pattern reflects an unpreparedness for war, the Battle provides a direct precedent As we have seen, with its depiction of the bathers being caught totally unprepared for the Pisan’s inevitable attack. it acts as "a cautionary [example] of the need for vigilance" [35] .

It is tempting to suggest that this work, with its unusual conjunction of war and bathing, may have been in Meere’s mind when he was conceiving Pattern. Certainly, with his longtime interest in murals, it would have been natural for Meere to turn to frescoes for inspiration, just as Michelangelo himself was inspired by classical reliefs and statues from ancient Rome [30]. Both artists’ works also share other elements – the emphasis on classical, healthy, naked (or near naked) figures, the concentration on highly-posed, somewhat artificial postures, an obsession with form and the depiction of a large number of figures in an extraordinarily complex tableau.

Both works also depict the scene as if the artist was standing in the water looking back at the shore. Both depict limbs trailing in the water. The figure in Battle holding a spear is reflected, reversed, by the man in Pattern holding the surfboard; and the upward-facing crook-armed figure at the far right on Battle recalls the woman with the beach ball in Pattern.

A further odd coincidence lies in the important role that cartoons have played in both paintings. Before Michelangelo’s Battle, cartoons had been considered simply as preparatory media, to be discarded or, at best, kept for future projects in the workshop the moment the painting was done [31]. However, it appears that Michelangelo always intended that his Battle cartoon should also have a life in itself as a self-sufficient work of art, irrespective of whether the “real” painting was ever completed. As such, it attracted great admiration from its contemporaries. Vasari noted how Michelangelo’s desire to show off his skills resulted in an extraordinary variety of extravagant poses which left other artists “seized with admiration and astonishment”, and that some, “after beholding figures so divine”, even declared “that there has never been seen any work… that can equal it in divine beauty of art”[32]. Michelangelo’s cartoon therefore acted as a “a school for craftsmen” and a monument to the importance of drawing [33].

Like Michelangelo, Meere also produced an elaborate cartoon for Pattern which he regarded as a self-sufficient work of art. He actually exhibited the cartoon at the Society of Artists 1939 Annual Exhibition, indicating not only the importance the project had for him [34], but also the significance that he attached to the cartoon itself.

It may also be that the educative role of Michelangelo’s work would have appealed to Meere, generally in his role as an art teacher and more specifically if he was using Pattern as a teaching piece for Freda Robertshaw. Finally, if Eadie is correct is saying that Pattern reflects an unpreparedness for war, the Battle provides a direct precedent As we have seen, with its depiction of the bathers being caught totally unprepared for the Pisan’s inevitable attack. it acts as "a cautionary [example] of the need for vigilance" [35] .

Conclusion

Charles Meere’s Australian Beach Pattern, with its enduring but elusive popular appeal, is an intriguing work that seems to invite alternative interpretations – particularly as objective evidence of the painter’s intention seems to be lacking. In this article we have examined some of those alternatives. Of course, what seems to be the most obvious or simple interpretation of a painting often turns out to be correct. Sometimes, however, it does not.

Hopefully, those revisiting Pattern, or those seeing it for the first time during its London sojourn, may be able to consider it with an open mind, receptive to the possibility that there may be considerably more to this work than meets the eye.

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014, 2015, 2015. 2016, 2017

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The origins of an Australian art Icon: Charles Meere's Australian Beach Pattern", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article.

Hopefully, those revisiting Pattern, or those seeing it for the first time during its London sojourn, may be able to consider it with an open mind, receptive to the possibility that there may be considerably more to this work than meets the eye.

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014, 2015, 2015. 2016, 2017

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The origins of an Australian art Icon: Charles Meere's Australian Beach Pattern", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article.

Endnotes

[1] Charles Meere (1890-1961), full name Mathew Charles Meere. For a more detailed biography, see Joy Eadie’s entry on Meere in Design & Art Australia Online http://www.daao.org.au/bio/version_history/charles-meere/biography/?p=1&revision_no=12 ; and her more comprehensive treatment in Discovering Charles Meere, Halstead Press, 2017. See also Linda Slutzkin and Dinah Dysart, Charles Meere (1890-1961), S H Ervin Gallery, National Trust of Aust (NSW), Sydney, 1987.

[2] This painting is held in the S H Ervin Gallery, Sydney. According to the myth, prospective suitors of Atalanta could win her hand by outrunning her in a footrace, with execution as the dire penalty for failure. Only one man was able to succeed, by distracting Atalanta during the race by rolling irresistible golden apples in her path.

[2a] Quoted in Slutzkin, op cit [note[1].

[3] Along with photographer Max Dupain’s Sunbaker (1937). Dupain’s studio was in the same Sydney building as Meere’s.

[4] The Gallery acquired the painting in 1965.

[5] For example, Robert Drewe’s The Bodysurfers.

[6] Joy Eadie, “In time of war: Charles Meere’s Australian Beach Pattern”, Art Monthly Australia, Iss 186, Summer 2005/6, p 26.

[6A] The most comprehensive treatment of the work is by Joy Eadie, in Discovering Charles Meere, Halstead Press, 2017.

[7] Slutzkin, op cit [note 1].

[8] Some would argue that how a painting is perceived by others is really all that matters. Of course, there is also the possibility that Meere was simply playing an elaborate joke by contrasting the “grand tragic themes of the European tradition” with what he may have perceived as the rather shallow pleasures of the new world: see Eadie, op cit at p 29. However, this does not seem likely, considering the years of concentrated effort and dedication that Meere put into the work.

[9] Eadie (In time of war), op cit at 27.

[10] Deborah Edwards, “Classical Allusions”, in Barry Pearce et al, Australian art in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, AGNSW, 2000, p 136.

[11] Christopher Allen, Art in Australia: from Colonisation to Postmodernism. Thames and Hudson, London. 1997, p 96. He also describes it as “a rather silly and artificial display of activity”.

[12] David Ellison, “Anne Zahalka’s Leisureland”, London Papers in Australian Studies No 13, Menzies Centre for Australian Studies, London, 2006, p 1.

[12A] Alastair Sooke, "Australia at the Royal Academy, Review", The Telegraph, 16 September 2013

[13] Eadie (In time of war), op cit at 27.

[14] Eadie (In time of war), op cit at 28. Meere also had close links with France, having fought there, and marrying a French nurse whom he met during a period recovering from his wounds. The couple spent their honeymoon visiting his friends' war graves, and later spent some time living and working in France (Eadie, see Endnote 1].

[15] For example, in satiric novels such as Miles Franklin and Dymphna Cusack’s highly-controversial Pioneers on Parade (1939). As the celebration of the 150th anniversary of British settlement in Australia, the event also attracted opposition from some Aborigines who described it as a "Day of Mourning and Protest".

[16] Eadie (In time of war), op cit at 27.

[17] As we shall see, this adjustment of gender balance had already been foreshadowed as far back as 1940, in Freda Robertshaw’s Australian Beach Scene.

[18] Anne O’Hehir, “Anne Sahalka: “How did we get to be here?”, Art and Australia, Autumn 2004, p 410.

[19] In accordance with practices at the time, the official figures excluded “full-blood Aboriginals” (Census of the Commonwealth of Australia, 30 June 1947.

[20] Linda Slutzkin, “Spartans in Speedos”, in Daniel Thomas and Ron Radford (eds), Creating Australia: 200 Years of Art 1788-1988, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 1988, p 176.

[21] Eadie (In time of war), op cit at 27. On Meere’s artistic irony, see also Eadie, in Exhibition Catalogue for Important Art from the Collection of Reg Grundy and Joy Chambers, June 2013, entry on Charles Meere’s Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend (1959).

[22] There are also some echoes here of Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830).

[23] Eadie (In time of war), op cit at 29.

[24] Eadie (In time of war), op cit at 30. It is interesting that the theme of being led astray by an apple also appears in Meere’s previous work Atalanta’s Eclipse, mentioned earlier: see end note [1].

[25] Robertshaw was originally a student of Meere's and became his apprentice in 1938. (It appears that there may be some direct copies of Pattern, usually identified by an attribution such as "Charles Meere and Studio". Journal reader Chris Jenkins has also drawn my attention to another copy by the American artist Fletcher Martin.) Robertshaw’s Australian Beach Scene was acquired for $475,000 in 1998 for the Reg Grundy and Joy Chambers-Grundy Collection, bidding against the National Gallery of Australia and the National Gallery of Victoria. At the time this was a record price for a work by an Australian woman artist. Her painting was one of the works which the Grundys chose to retain rather than include it in the partial sale of their collection in 2012. Sadly, Robertshaw would never know about this record price – she had died the year before. See John Cruthers, Introduction to Exhibition Catalogue for Important Art from the Collection of Reg Grundy and Joy Chambers, June 2013

[26] Harold Osborne (ed), The Oxford Companion to Art, Book Club Associates, London, 1978 at p 116-117.

[27] Also known as Bastiano da Sangallo.

[28] Jonathan Jones, “Michelangelo’s naked courage in the The Battle of Cascina”, The Guardian, 3 June 2011 http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2011/jun/03/michelangelo-battle-of-cascina . More generally, see Jonathan Jones, The Lost Battles: Leonardo, Michelangelo and the Artistic Duel that Defined the Renaissance, Alfred A Knopf, New York, 2010.

[29] Joost Keizer, “Michelangelo, Drawing and the Subject of Art”, The Art Bulletin 93:3 (Sept 2011), p 304.

[30] Osborne, op cit at 117.

[31] Keizer, op cit.

[32] Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, Everyman’s Library, London, 1996, at 657. Some of the poses are certainly extravagant. The figure at centre front seems to be twisted to an impossible degree.

[33] Vasari, op cit at 658; Keizer, op cit. Kenneth Clark has said, “These battle cartoons of Leonardo and Michelangelo are the turning-point of the Renaissance… It is not too fanciful to say that they initiate the two styles which sixteenth century painting was to develop – the Baroque and the Classical”: cited in Osborne, op cit at 117.

[34] Eadie (Design and Art), op cit.

[35] Robert Williams, Letter to Editor, The Art Bulletin, vol XCV No 4 (Dec 2013) at 656.

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The origins of an Australian art Icon", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home