the Isenheim Altarpiece Pt 1: Pestilence and the concert of angels

|

By Philip McCouat

Almost exactly five hundred years ago, Matthias Grűnewald embarked on his monumental masterwork, the Isenheim Altarpiece. It would take him four years to complete, and the huge multi-panelled work he created has been called “the most moving and impressive series of religious paintings of the entire Middle Ages”[1]. Yet, within less than two centuries, Grűnewald’s reputation had seemingly fallen into oblivion. Even today, after a considerable revival of scholarly interest in the artist, his work is relatively little-known to the general public outside Germany |

-----------------------------------

For more on diseases For more articles on art and disease, see:

|

There are probably a number of reasons for this discrepancy. Although Grűnewald was well-known during his lifetime, he evidently lived a secluded existence [2], with the result that there was surprisingly little written about him during his lifetime. In fact, his elusiveness extends even to his real identity – the very name “Matthias Grűnewald” seems to be a case of misidentification, and his real name was in fact Mathis Gothart Neithart [3].

Furthermore, his works were also had a rather localised profile. The few that have survived are solely on religious subjects and most remain in smaller museums or the churches for which they were created, mainly in Germany, rather than being exhibited in major mainstream museums [4]. Grűnewald was also not what is regarded as a “progressive” painter – unlike his contemporary, the Italian-influenced Albrecht Dűrer, he resisted some of the developments of the Renaissance and his world view remained strongly influenced by medieval concerns. On top of this, his work is also difficult to pigeonhole. In one sense, it can be seen simply as “a sermon in pictures” [5], but at the same time it combines elements of extreme, sometimes shocking realism, intense religious emotion and colour and a fantastic, almost surreal, imagination.

In this article, we cannot hope to discuss the Altarpiece in the detail it demands, but will instead focus on just two contrasting aspects. In the first part, we will look at the work’s apparent role as a comforter and healer of the sick. In the second part, we will attempt to unravel some of the mysteries that have surrounded one of its central panels. Before we do that, however, we need to get some idea of what the Altarpiece looks like.

Furthermore, his works were also had a rather localised profile. The few that have survived are solely on religious subjects and most remain in smaller museums or the churches for which they were created, mainly in Germany, rather than being exhibited in major mainstream museums [4]. Grűnewald was also not what is regarded as a “progressive” painter – unlike his contemporary, the Italian-influenced Albrecht Dűrer, he resisted some of the developments of the Renaissance and his world view remained strongly influenced by medieval concerns. On top of this, his work is also difficult to pigeonhole. In one sense, it can be seen simply as “a sermon in pictures” [5], but at the same time it combines elements of extreme, sometimes shocking realism, intense religious emotion and colour and a fantastic, almost surreal, imagination.

In this article, we cannot hope to discuss the Altarpiece in the detail it demands, but will instead focus on just two contrasting aspects. In the first part, we will look at the work’s apparent role as a comforter and healer of the sick. In the second part, we will attempt to unravel some of the mysteries that have surrounded one of its central panels. Before we do that, however, we need to get some idea of what the Altarpiece looks like.

The Altarpiece

The Altarpiece, by far Grűnewald’s best–known work, was commissioned in about 1512 for the chapel of a hospital and monastery run by the Order of Hospitallers of St Anthony. The hospital was in Isenheim, a small town in north-eastern France, close to the German border [6].

The Altarpiece is extraordinarily complex. It consists of nine large oil paintings on separate, hinged wooden panels. These have been designed so that they can be opened out into three separate configurations to display different combinations of scenes. You can get an idea of how it was intended to work by accessing the demonstration on a miniature model at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BN2VvXtjkjI

When the altarpiece is in its “closed” configuration – its normal display format – the viewer is confronted with a central panel depicting the Crucifixion, with side panels showing St Sebastian (patron saint of plague victims) and St Anthony (patron saint of the sick). The is also a predella, below the central panel, depicting the Lamentation. The Crucifixion panel alone is 2.7 metres (8’10”) high by 3.07 metres (10’) wide. Each wing is 76 cm (2’6”), so overall the display is some 3.83 metres (15’) wide. With dimensions such as these, the Altarpiece not only embraces viewers, it practically engulfs them.

The central panel of the Crucifixion is actually split vertically and can be opened out like cupboard doors. When this is done, a quite different set of three paintings appear, dominated by a central Nativity panel, and flanked by an Annunciation and a Resurrection. When these panels are in turn opened out in the same way, they reveal yet another inner configuration, consisting of a central wooden carving of St Anthony, flanked by other saints [7], together with painted side panels showing the Meeting of St Anthony and St Paul, and the Torment of St Anthony.

The Altarpiece is now housed in a partly dismantled but more easily viewable state, at the Musée Unterlinden in Colmar [Fig 1], just a few kilometres from its original location at Isenheim, where it was removed for safekeeping after the French Revolution [8].

The Altarpiece is extraordinarily complex. It consists of nine large oil paintings on separate, hinged wooden panels. These have been designed so that they can be opened out into three separate configurations to display different combinations of scenes. You can get an idea of how it was intended to work by accessing the demonstration on a miniature model at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BN2VvXtjkjI

When the altarpiece is in its “closed” configuration – its normal display format – the viewer is confronted with a central panel depicting the Crucifixion, with side panels showing St Sebastian (patron saint of plague victims) and St Anthony (patron saint of the sick). The is also a predella, below the central panel, depicting the Lamentation. The Crucifixion panel alone is 2.7 metres (8’10”) high by 3.07 metres (10’) wide. Each wing is 76 cm (2’6”), so overall the display is some 3.83 metres (15’) wide. With dimensions such as these, the Altarpiece not only embraces viewers, it practically engulfs them.

The central panel of the Crucifixion is actually split vertically and can be opened out like cupboard doors. When this is done, a quite different set of three paintings appear, dominated by a central Nativity panel, and flanked by an Annunciation and a Resurrection. When these panels are in turn opened out in the same way, they reveal yet another inner configuration, consisting of a central wooden carving of St Anthony, flanked by other saints [7], together with painted side panels showing the Meeting of St Anthony and St Paul, and the Torment of St Anthony.

The Altarpiece is now housed in a partly dismantled but more easily viewable state, at the Musée Unterlinden in Colmar [Fig 1], just a few kilometres from its original location at Isenheim, where it was removed for safekeeping after the French Revolution [8].

Saint Anthony's fire and The healing power of art

During the 11th century, during a fatal epidemic of a hideously disfiguring disease, it had come to be believed that the victims could gain relief by seeking intercession from St Anthony, one of the earliest Christian monks [9]. In 1095 a nobleman whose son had experienced just such a miraculous cure founded the Antonine Order in the French town where the saint’s relics were held [10]. The Order’s influence spread widely and it would eventually own over 300 hospitals, including the major complex at Isenheim.

The Order combined spirituality with a practical, charitable approach. They provided accommodation to pilgrims and cared for the sick, including victims of the Black Death [11]. Most relevantly for our purposes, they specialised in diagnosing and treating that mysterious disfiguring disease, which became known as St Anthony’s Fire, or Holy Fire (ignis sacer).

The disease, which would recur in devastating epidemics throughout the Middle Ages [12], caused agonising skin eruptions that blackened and became gangrenous, often requiring amputations [13]. These must have been extraordinarily pioneering operations, as amputations were not fully developed until Ambroise Paré’s innovations in the late 16th century [14]. The pain was experienced by victims as an intense burning sensation (hence the “fire”), and popular representations of the disease at the time often show its victims with a crutch under one arm and the other arm actually in flames [15]. Victims also suffered from uncontrollable convulsions, could be delusional, and go bezerk. Very often, they died.

The cause of the disease, not identified until the following century, was a poison from a fungus (“ergot”) that attached itself to rye and contaminated the flour used to make rye bread [16]. The disease is now called ergotism, and is rare, though there were a number of outbreaks into the early nineteenth century and a fatal outbreak in a French town as recently as 1951 which was attributed at the time to the disease [17].

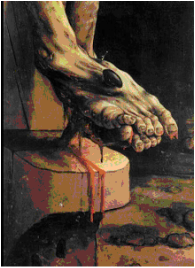

This healing function of the hospital appears to have been crucial in the commissioning of the Altarpiece and also appears to have had a major effect on its contents [18]. Patients at the hospital would presumably have been be afflicted with both agonising pain and mortal fear. They may also have had deep feelings of guilt arising from the belief that Satan had caused their disease as a result of their sins. Those who had access to the chapel, even if only infrequently, could therefore easily identify with the torments suffered by both Christ and St Anthony. In depicting these, Grűnewald certainly does not hold back. In a depiction not common at the time, Christ is portrayed as a writhing, emaciated, contorted, sore-blotched body in terminal agony, complete with dirty toenails, cadaverous greenish skin, dislocated shoulders and hands clawed in pain (Figs 2 and 3). The general nightmarishness is accentuated by the dark setting, reflecting the "darkness all over the earth" that the Bible records as occurring at the time Christ commended his spirit to God [18A].

The Order combined spirituality with a practical, charitable approach. They provided accommodation to pilgrims and cared for the sick, including victims of the Black Death [11]. Most relevantly for our purposes, they specialised in diagnosing and treating that mysterious disfiguring disease, which became known as St Anthony’s Fire, or Holy Fire (ignis sacer).

The disease, which would recur in devastating epidemics throughout the Middle Ages [12], caused agonising skin eruptions that blackened and became gangrenous, often requiring amputations [13]. These must have been extraordinarily pioneering operations, as amputations were not fully developed until Ambroise Paré’s innovations in the late 16th century [14]. The pain was experienced by victims as an intense burning sensation (hence the “fire”), and popular representations of the disease at the time often show its victims with a crutch under one arm and the other arm actually in flames [15]. Victims also suffered from uncontrollable convulsions, could be delusional, and go bezerk. Very often, they died.

The cause of the disease, not identified until the following century, was a poison from a fungus (“ergot”) that attached itself to rye and contaminated the flour used to make rye bread [16]. The disease is now called ergotism, and is rare, though there were a number of outbreaks into the early nineteenth century and a fatal outbreak in a French town as recently as 1951 which was attributed at the time to the disease [17].

This healing function of the hospital appears to have been crucial in the commissioning of the Altarpiece and also appears to have had a major effect on its contents [18]. Patients at the hospital would presumably have been be afflicted with both agonising pain and mortal fear. They may also have had deep feelings of guilt arising from the belief that Satan had caused their disease as a result of their sins. Those who had access to the chapel, even if only infrequently, could therefore easily identify with the torments suffered by both Christ and St Anthony. In depicting these, Grűnewald certainly does not hold back. In a depiction not common at the time, Christ is portrayed as a writhing, emaciated, contorted, sore-blotched body in terminal agony, complete with dirty toenails, cadaverous greenish skin, dislocated shoulders and hands clawed in pain (Figs 2 and 3). The general nightmarishness is accentuated by the dark setting, reflecting the "darkness all over the earth" that the Bible records as occurring at the time Christ commended his spirit to God [18A].

For his part, St Anthony is shown as being beset by numerous fantastical and monstrous demons in the nightmarish Torment of St Anthony (Fig 4). The identification of the patients with these images was made even more explicit in the lower left of the Torment by the ghastly depiction of a floundering, bloated creature with weeping lesions, witnessing the horrifying scene [19]

|

But while it challenged and confronted the already-weakened sufferers, the Altarpiece also offered them the opportunity of solace. In modern parlance, it offered a kind of ultra-tough love. The patients could meet their awful challenge by trusting their faith and drawing strength from the fortitude shown by both Christ and the saint. Hopefully, they could draw comfort from the ultimate triumph of Christ in the Resurrection /Ascension and from Anthony’s elevation to sainthood.

And in the Nativity, which we discuss further below, they could receive assurance that placing their trust in Christ could confound the designs of Satan who had cruelly struck them down with their disease. |

In effect, then, the images in the Altarpiece sternly tested sufferers’ faith but also provided spiritual and psychological reward for those who were able and prepared to commit to it.

An enigmatic concert of angels

It is with something like a feeling of relief that we now turn to the Nativity, the central panel of the second view of the Altarpiece. On the right is a Virgin and Child, on the left an concert of angels inside a gilded temple. This scene, seemingly innocent, raises some curious puzzles (Fig 5).

Of the angels, only three are actually playing instruments, with the others either singing or in attitudes of reverence. The principal player is the angel in the left foreground, who is playing a viola da gamba. At the time, this instrument, related to the cello [20], had only recently evolved, so this is one of its earliest depictions in art The odd aspect of this depiction, however, is that the angel appears to be holding the bow backwards, a technique that would make playing extraordinarily awkward, if not almost impossible (fig 6).

A number of explanations have been proposed for this curiosity. The first possibility is, of course, that it is simply a mistake by the artist, due to the relative novelty of the instrument [21]. However, others have argued that the positioning of the angel’s hand is quite deliberate and meaningful. For example, the Hagens suggest that the angels’ orchestra is linked to the music of the spheres, and that the pose reflects the belief that angels make music differently to humankind [22]. Alternatively, it has been said that the position of the angel’s arm serves the purpose of balancing the composition, presumably by unifying the principal angel with the other angels. More controversially, it has been suggested that the angel represents Venus, the morning star, heralding the dawn of a new day represented by the birth of Christ, and that the function of the bowing technique is to direct the viewer’s attention to the point of generation between the angel’s legs [23].

Whichever explanation is favoured, what then do we make of the equally-idiosyncratic dagger-like bowing technique of the strange greenish-black feathered creature directly behind the main angel? This creature is markedly different from the rest of the angels (Fig 7). He is entirely feathered, seemingly unclad, with a sickly, gangrenous colouring. His fingers are elongated and reptilian and there is a strange crest on his head. He is distinctly dark, with similar colour tones to the-seemingly-disembodied impish heads emerging from the black recesses of the space. His attention is not on the music and, unlike the other angels, his gaze is not directed towards the Virgin and Child. Instead, he is staring fixedly at the ghostly vision of God high in the heavens. His reaction to this sight is difficult to read, but he is clearly not exultant or ecstatic. Rather, he appears to be somewhat baffled, with an air of dawning realisation, trepidation or even dread.

Whichever explanation is favoured, what then do we make of the equally-idiosyncratic dagger-like bowing technique of the strange greenish-black feathered creature directly behind the main angel? This creature is markedly different from the rest of the angels (Fig 7). He is entirely feathered, seemingly unclad, with a sickly, gangrenous colouring. His fingers are elongated and reptilian and there is a strange crest on his head. He is distinctly dark, with similar colour tones to the-seemingly-disembodied impish heads emerging from the black recesses of the space. His attention is not on the music and, unlike the other angels, his gaze is not directed towards the Virgin and Child. Instead, he is staring fixedly at the ghostly vision of God high in the heavens. His reaction to this sight is difficult to read, but he is clearly not exultant or ecstatic. Rather, he appears to be somewhat baffled, with an air of dawning realisation, trepidation or even dread.

Drawing on a number of sources, Ruth Melinkoff has plausibly interpreted these distinguishing features as indicating that this figure is actually none other than Lucifer, the Devil himself [24]. According to tradition, Lucifer had been a high-ranking but overly-ambitious angel who was banished from heaven because of his pride. He later became identified with the Devil, exercising his considerable powers to tempt humans into the types of sinful behaviour to which they were prone, and to visit illness and suffering upon them. The coming of Christ would therefore have been a double blow for him. Firstly, Christ’s birth, death and ultimate resurrection meant that humans who committed to faith in Christ now had an avenue to achieving redemption and everlasting life, no matter what the Devil did. This directly reflected the situation of St Anthony, who was able to use his faith in Christ to withstand and overcome the Devil’s torments. Secondly, Christ’s direct capacity to heal, or to drive out the demons who caused suffering, meant that the results of the Devil’s efforts could potentially be undone. This directly related to the situation of the patients.

If this identification of the Devil is correct, the Nativity can be seen as having a quite specific function: in a particularly dramatic way, it reminded its viewers of the very moment at which Satan first realised that his nemesis, in the form of Christ, had arrived. □

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

How to cite this article

This article may be cited as:

Philip McCouat, "The Isenheim Altarpiece Part 1: Pestilence and the Concert of Angels", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

You may also enjoy….

If you enjoyed this article, you may also be interested in:

If this identification of the Devil is correct, the Nativity can be seen as having a quite specific function: in a particularly dramatic way, it reminded its viewers of the very moment at which Satan first realised that his nemesis, in the form of Christ, had arrived. □

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

How to cite this article

This article may be cited as:

Philip McCouat, "The Isenheim Altarpiece Part 1: Pestilence and the Concert of Angels", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

You may also enjoy….

If you enjoyed this article, you may also be interested in:

Endnotes

[1] Burkhard, A, Matthias Grünewald: Personality and Accomplishment, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1936 at 25.

[2] Piper, D, The Illustrated History of Art, Chancellor Press, London, 2004 at 151; see also Ziermann, H with Beissel, E, Matthias Grűnewald, Prestel, Munich/New York 2001 at 31

[3] Thus explaining the monogram MGN that appears on some of his works: Osborne, H (ed), The Oxford Companion to Art, Oxford University Press, 1978, entry on Mathias Grűnewald.

[4] Meiser,S, "A Masterpiece Born of Saint Anthony's Fire", Smithsonian Magazine, September 1999 .

[5] Gombrich, E H, The Story of Art, Phaidon, London, 1970 at 257.

[6] The Altarpiece was eventually relocated to the Musée Unterlinden in Colmar, Alsace, in 1852.

[7] The sculptures are by Nicholas von Hagenau.

[8] Its temporary war-time relocation to Munich, and subsequent relocation back to Colmar, inspired intense nationalist fervour in Germany.

[9] Saint Anthony (c.251-356) was a hermit in Egypt and one of the earliest Christian monks. He is considered the founder and father of organised Christian monasticism and is the saint who protects against fire, epilepsy and infection. He is commonly referred to as St Anthony the Great, to distinguish him from the much later St Anthony of Padua..

[10] The town was La Motte-Saint-Didier in south eastern France. It was later renamed Saint-Antoine-l’Abbaye, in honour of the saint..

[11] Hagen, R-M and R, What Great Paintings Say, Taschen, Cologne, 2003, vol 2 at 128.

[12] Similar outbreaks had been reported as far back as ancient Greece.

[13] Hayum, A, “The Meaning and Function of the Isenheim Altarpiece: the Hospital Context Revisited, The Art Bulletin, Vol 59, No 4 Dec 1977, 501, at 509.

[14] Porter, R, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, Fontana, London 1999 at 188.

[15] Hayum, op cit at 507.

[16] The psychotropic lysergic acid diethyl-amide (LSD) is a modern synthetic derivative of ergot.

[17] The outbreak was at Pont-Saint-Esprit. For a popular account, see Fuller Jr, J G, The Day of St Anthony’s Fire, McMillan, New York, 1968..

[18] Hayum, op cit at esp 511 ff; see also Hayum, A, The Isenheim Altarpiece: God’s Medicine and the Painter’s Vision, Princeton University Press, 1989.

[18A] Luke 23:44. Luke's comment that "the sun was darkened" may have resonated with the artist, who had himself witnessed a total eclipse of the sun in 1502.

[19] It also may or may not be coincidental that when the front panels of the Crucifixion are opened sequentially, the crucified Christ appears to have an arm amputated, dramatically reflecting the condition of many of the Fire sufferers. However, this would only be effective if the sufferers were there at the time when the transition to the inner configuration was being carried out.

[20]. The viola da gamba (also called a bass viola) is reminiscent of a cello, though produces a softer, rounder sound. It is held between that the legs (gamba means “leg” in Italian), normally has six or seven strings, and a fret, like a guitar. It is played with a bow. It may be distinguished from the second angel’s viola da braccio (braccio = “arm”), which has four strings and is held like a violin.

[21] Though it has to be said that Grűnewald did not seem to have been the type to do anything without careful consideration of its implications.

[22] Hagen, op cit at 127. However, not all the angels share this odd posture.

[23] Rasmussen, M, “Viols, Violists and Venus in Grűnewald’s Isenheim Altar”, Early Music vol 29, No 1 2001, at 61ff. This interpretation seems adventurous.

[24] Melinkoff, R, The Devil at Isenheim: Reflections on Popular Belief in Grunewald’s Altarpiece, University of California Press, 1988. Melinkoff also suggests that the panel as a whole suggests the emergence of Christianity from the darkness of superstition and evil, represented by the Lucifer and the interior of the chapel. On this interpretation, the radiant figure emerging from the temple and away from the “bad” angels is Ecclesia, the symbol of the Church.

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

[2] Piper, D, The Illustrated History of Art, Chancellor Press, London, 2004 at 151; see also Ziermann, H with Beissel, E, Matthias Grűnewald, Prestel, Munich/New York 2001 at 31

[3] Thus explaining the monogram MGN that appears on some of his works: Osborne, H (ed), The Oxford Companion to Art, Oxford University Press, 1978, entry on Mathias Grűnewald.

[4] Meiser,S, "A Masterpiece Born of Saint Anthony's Fire", Smithsonian Magazine, September 1999 .

[5] Gombrich, E H, The Story of Art, Phaidon, London, 1970 at 257.

[6] The Altarpiece was eventually relocated to the Musée Unterlinden in Colmar, Alsace, in 1852.

[7] The sculptures are by Nicholas von Hagenau.

[8] Its temporary war-time relocation to Munich, and subsequent relocation back to Colmar, inspired intense nationalist fervour in Germany.

[9] Saint Anthony (c.251-356) was a hermit in Egypt and one of the earliest Christian monks. He is considered the founder and father of organised Christian monasticism and is the saint who protects against fire, epilepsy and infection. He is commonly referred to as St Anthony the Great, to distinguish him from the much later St Anthony of Padua..

[10] The town was La Motte-Saint-Didier in south eastern France. It was later renamed Saint-Antoine-l’Abbaye, in honour of the saint..

[11] Hagen, R-M and R, What Great Paintings Say, Taschen, Cologne, 2003, vol 2 at 128.

[12] Similar outbreaks had been reported as far back as ancient Greece.

[13] Hayum, A, “The Meaning and Function of the Isenheim Altarpiece: the Hospital Context Revisited, The Art Bulletin, Vol 59, No 4 Dec 1977, 501, at 509.

[14] Porter, R, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, Fontana, London 1999 at 188.

[15] Hayum, op cit at 507.

[16] The psychotropic lysergic acid diethyl-amide (LSD) is a modern synthetic derivative of ergot.

[17] The outbreak was at Pont-Saint-Esprit. For a popular account, see Fuller Jr, J G, The Day of St Anthony’s Fire, McMillan, New York, 1968..

[18] Hayum, op cit at esp 511 ff; see also Hayum, A, The Isenheim Altarpiece: God’s Medicine and the Painter’s Vision, Princeton University Press, 1989.

[18A] Luke 23:44. Luke's comment that "the sun was darkened" may have resonated with the artist, who had himself witnessed a total eclipse of the sun in 1502.

[19] It also may or may not be coincidental that when the front panels of the Crucifixion are opened sequentially, the crucified Christ appears to have an arm amputated, dramatically reflecting the condition of many of the Fire sufferers. However, this would only be effective if the sufferers were there at the time when the transition to the inner configuration was being carried out.

[20]. The viola da gamba (also called a bass viola) is reminiscent of a cello, though produces a softer, rounder sound. It is held between that the legs (gamba means “leg” in Italian), normally has six or seven strings, and a fret, like a guitar. It is played with a bow. It may be distinguished from the second angel’s viola da braccio (braccio = “arm”), which has four strings and is held like a violin.

[21] Though it has to be said that Grűnewald did not seem to have been the type to do anything without careful consideration of its implications.

[22] Hagen, op cit at 127. However, not all the angels share this odd posture.

[23] Rasmussen, M, “Viols, Violists and Venus in Grűnewald’s Isenheim Altar”, Early Music vol 29, No 1 2001, at 61ff. This interpretation seems adventurous.

[24] Melinkoff, R, The Devil at Isenheim: Reflections on Popular Belief in Grunewald’s Altarpiece, University of California Press, 1988. Melinkoff also suggests that the panel as a whole suggests the emergence of Christianity from the darkness of superstition and evil, represented by the Lucifer and the interior of the chapel. On this interpretation, the radiant figure emerging from the temple and away from the “bad” angels is Ecclesia, the symbol of the Church.

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME