Art in a Speeded Up World - Part 3

By Philip McCouat

|

Overview

Part 1: Changing concepts of time Part 2: The 'new' time in literature Part 3: The 'new' time in painting |

Other articles on photography:

Early influences of photography on art Why wasn’t photography invented earlier? -------------------------------------------------------- |

Part 3: The 'new' time in painting

Creatively,

of course, it was easier to incorporate the new time concepts in literature rather

than in visual art [100]. Writers have the liberty of explaining and

describing, whereas painters face much greater challenges in conveying abstract

concepts or detailed reasoning. So it is not so surprising that artists took

more time to assimilate the changes and to attempt to incorporate them into

their work.

Importance of time

Initially, and not surprisingly, painters reacted in a fairly literal way, by producing paintings which simply reflected the new importance of time in daily life. So, for example, the extraordinary extent to which the public had become more time-conscious became the subject of paintings such as George Elgar Hicks’ The General Post Office: One Minute to Six (1860) (Fig 7a). This work shows a wide spectrum of London society crowding to catch the last post at 6 o’clock. This daily rush had acquired legendary status, being seen as a true modern phenomenon, a living symbol not just of the rapid spread of communication but of the accelerating pace of life throughout Victorian Britain. The temporal precision of the title of the painting, incidentally, was no exaggeration – since 1855 clocks at the Post Office had been corrected daily by electric telegraph signals from the Royal Observatory at Greenwich [101].

A similar theme appears in William Powell Frith’s blockbuster The

Railway Station (1862) – the painting reproduced on our masthead – which

depicts crowds of all social classes crowding to board the Great Western

Railway train at Paddington Station. At the extreme right, two London detectives are

arriving in the nick of time to arrest a ‘fugitive from justice, his foot on

the step of the carriage that would take him to freedom’[102]. The incident is

overlaid, by a trick of perspective, onto the area of a newspaper held by a man

reading in the carriage, ‘like an item inserted into the daily news’. Newsboys

feature on from both sides of the painting, and the crushing urgency of the

crowd at the left underlines the time pressures imposed by the still-new

technology [103].

The contrast between old or natural time, and the new time driven by technological changes, also became the subject of JMW Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed – the Great Western Railway (1844). This work shows a vast Thames River being spanned by the modern energy of the railway [103a]. The barely-visible dancing maidens on the bank of the river and the plough in a distant field signify a society that is fading before the impact of a scientific revolution [104]. The hare racing in front of the train contrasts ‘natural’ speed with the vastly superior speed of the modern locomotive, a speed so rapid that the viewer’s perception is blurred, prompting contemporary viewers to feel that the train was about to burst out of the picture [105]. As one reviewer of the painting commented, ‘[M]eanwhile there comes a train upon you, really moving at the rate of fifty miles per hour, and which the reader had best make haste to see, lest it should dash out of the picture, and be away up Charing Cross through the wall opposite’ [106]. Schama suggests that the painting represents a clear recognition by Turner that ‘while once the river had been the favoured metaphor for the flow of time, modern history was already being compared to the runaway force of the locomotive’ [107].

A similar though less dramatic contrast between the natural river and the mechanical train appears in Monet’s The Railway Bridge at Argenteuil [108]. River-time is unbroken and continuous, whereas the crossing of the two trains on the bridge invokes the precise timekeeping needed for railway timetables. The sailing boats and the two figures on the bank suggest the more flexible subjective notion of leisure time, unconstrained by such strict schedules [109].

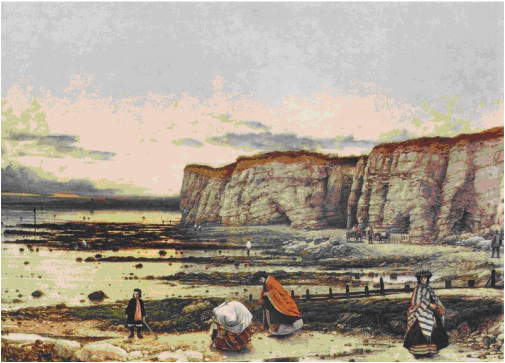

While Hicks’ painting reflected personal and social issues, and Turner’s reflected technological concerns, William Dyce ventured beyond both of these to portray the new awareness of cosmic time in human life, in his post-Darwinian Pegwell Bay, Kent: A Recollection of October 5th 1858 (Fig 8) [109a]. The time-specificity of the title, and the immediacy of the poses of the woman at right and child at left, suggest the painting’s sense of immediate present. The faint appearance of a comet in the sky [110] is a reminder of the almost unimaginable concepts of time and distance that had recently been claimed by astronomers. The new ‘geological’ time is suggested by the women collecting shells or fossils, and by the eroded chalk cliffs. It has even been speculated that the rather mournful colours of the painting reflect the nostalgia of the artist – who was also a minister of religion – for the old certainties. In this respect, the location of the painting is significant. Pegwell Bay was the supposed site of the first Christian missionary St Augustine’s arrival in Britain, but it was also a centre famous for its prehistoric fossils [111].

The contrast between old or natural time, and the new time driven by technological changes, also became the subject of JMW Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed – the Great Western Railway (1844). This work shows a vast Thames River being spanned by the modern energy of the railway [103a]. The barely-visible dancing maidens on the bank of the river and the plough in a distant field signify a society that is fading before the impact of a scientific revolution [104]. The hare racing in front of the train contrasts ‘natural’ speed with the vastly superior speed of the modern locomotive, a speed so rapid that the viewer’s perception is blurred, prompting contemporary viewers to feel that the train was about to burst out of the picture [105]. As one reviewer of the painting commented, ‘[M]eanwhile there comes a train upon you, really moving at the rate of fifty miles per hour, and which the reader had best make haste to see, lest it should dash out of the picture, and be away up Charing Cross through the wall opposite’ [106]. Schama suggests that the painting represents a clear recognition by Turner that ‘while once the river had been the favoured metaphor for the flow of time, modern history was already being compared to the runaway force of the locomotive’ [107].

A similar though less dramatic contrast between the natural river and the mechanical train appears in Monet’s The Railway Bridge at Argenteuil [108]. River-time is unbroken and continuous, whereas the crossing of the two trains on the bridge invokes the precise timekeeping needed for railway timetables. The sailing boats and the two figures on the bank suggest the more flexible subjective notion of leisure time, unconstrained by such strict schedules [109].

While Hicks’ painting reflected personal and social issues, and Turner’s reflected technological concerns, William Dyce ventured beyond both of these to portray the new awareness of cosmic time in human life, in his post-Darwinian Pegwell Bay, Kent: A Recollection of October 5th 1858 (Fig 8) [109a]. The time-specificity of the title, and the immediacy of the poses of the woman at right and child at left, suggest the painting’s sense of immediate present. The faint appearance of a comet in the sky [110] is a reminder of the almost unimaginable concepts of time and distance that had recently been claimed by astronomers. The new ‘geological’ time is suggested by the women collecting shells or fossils, and by the eroded chalk cliffs. It has even been speculated that the rather mournful colours of the painting reflect the nostalgia of the artist – who was also a minister of religion – for the old certainties. In this respect, the location of the painting is significant. Pegwell Bay was the supposed site of the first Christian missionary St Augustine’s arrival in Britain, but it was also a centre famous for its prehistoric fossils [111].

_ At an even more fundamental level, the recent changes in thinking about the past played a role in changing ideas about what actually qualified as art. When prehistoric rock paintings were first re-discovered in the seventeenth century, the viewers’ lack of any temporal framework had meant that the works were simply regarded as hardly worthy of interest. From about the mid nineteenth century, however, as people’s concepts of time expanded to include the perspective of vast eons of prehistoric antiquity, they became more equipped to see the paintings in their proper context, as extraordinary artistic creations. The result was a soaring of interest in Palaeolithic art [112].

Time and reality

he additional insights into temporal reality that were being provided, particularly by photography, also started being reflected in painting. For example, it seems likely that Muybridge’s stop-action photography (see Part 1) may have inspired Degas’ renewed interest in depicting racehorses – particularly in intermediate positions not normally perceived by humans [113]. It also influenced the portrayal of horses in Eakins’ The Fairman Rogers Four in Hand (1879) [114] and the diving boy in his oddly-frozen Swimmers (1885) [115]. Artists such as Meissonnier and Remington rushed to correct their former ‘rocking horse’ style depictions of galloping horses. Suddenly there was an outbreak of battle pictures, showing horses charging in every direction, with all four legs off the ground. Not since 1815 had the Battle of Waterloo been so popular [116].

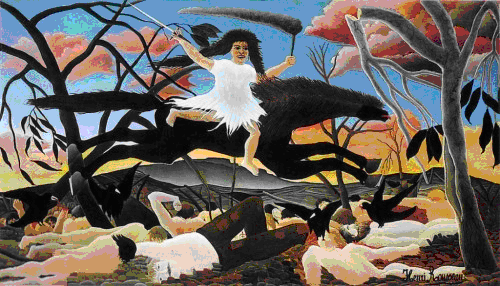

Of course, the issue is not really about how horses gallop – rather it is about the role of objective reality. Changes in one’s perception of objective reality will matter greatly for a painter of realist battle scenes, but may be irrelevant for those who are less literal minded. So, for example, Seurat is still using the‘old’ style – extremely effectively – in Le Cirque (1891), as is Toulouse-Lautrec in The Jockey (1899) and Rousseau in War (1894) (Fig 9). These objectively-incorrect depictions are quite deliberate, and seem an essential part of the composition. For example, it is likely that a depiction of a biomechanically-correct galloping horse bestriding the scene of human devastation in War would look ridiculous in this context.

Of course, the issue is not really about how horses gallop – rather it is about the role of objective reality. Changes in one’s perception of objective reality will matter greatly for a painter of realist battle scenes, but may be irrelevant for those who are less literal minded. So, for example, Seurat is still using the‘old’ style – extremely effectively – in Le Cirque (1891), as is Toulouse-Lautrec in The Jockey (1899) and Rousseau in War (1894) (Fig 9). These objectively-incorrect depictions are quite deliberate, and seem an essential part of the composition. For example, it is likely that a depiction of a biomechanically-correct galloping horse bestriding the scene of human devastation in War would look ridiculous in this context.

The “fleeting moment” effect that photography fostered also started appearing in many paintings – for example Toulouse-Lautrec’s At the Moulin Rouge [fig 10] or Cassatt’s Mrs Cassatt Reading to her Grandchildren (1880). Degas’ Place de la Concorde similarly shows radical cropping, a spontaneous feel to the characters due to their unconventional positioning, and an unusual composition lacking any middle ground – all effects that are capable of being attributed to photographic immediacy [117].

_ Of course, fast as photography was, it had its limits. Photographic blurring could result from the combination of moving objects and (relatively) slower exposure times. Although this effect was generally considered to be a defect, it was sometimes mimicked in paintings. In Munch’s photographically-based Man and Woman II, for example, a man stands out as a dynamic blurred shadow, as a result of moving away from a position ‘too close’ to the camera [118]. It is also arguable that the ‘smudged’ figures in Monet’s Boulevarde des Capucines are based on the blurred figures in an 1868 photo [119]. However, in the painting, unlike the photograph, everything is a bit blurred, not just the moving figures. Furthermore, the painted figures are actually recognisable as people, whereas the photographed figures do not look like people at all [120].

Other depictions of the effects of time

It was not just the importance of time that artists were starting to reflect in their work. They also began attempting to convey the effects of time in different ways. In On the Beach at Boulogne (1869), Manet, in accordance with his determination to ‘work with what I see’ [121] presents a number of small component scenes, with each being executed separately and then combined into a wide, flattened panorama. McClain argues that this resulted from Manet’s refusal to compromise the immediate experience of seeing each component as his eyes moved about. To take in the scene, the viewer, like Manet, therefore has to jump from group to group. Because of this part-by-part reading, it is argued, the work can only be seen in time [122].

It seems that Claude Monet also wanted the viewer to live for longer with his paintings. He began applying effects similar to those of stop-action photography with seemingly static objects by painting subjects such as Rouen Cathedral or haystacks in multiple series, showing the light effects on the same subject at different times of the day, seasons and climatic conditions [123]. These works represented an attempt to incorporate the dimension of time in the paintings [124]. At a serial exhibition of the Rouen paintings, one commentator imagined a ‘perfect equivalence of art and phenomenon – a lasting vision not of twenty, but a hundred, a thousand, a million states of the eternal cathedral in the immense cycles of the sun’ [125].

Monet himself commented, ‘One does not paint a landscape ... One paints an impression of an hour of the day’. He called this approach ‘instantaneity’. He added that these paintings acquired ‘their full value only by the comparison and succession of the whole series’ [126]. In a sense, Monet is presenting history, not traditionally as a representation of the past, but as collection of representations of the evolving ‘now’. This can also be seen as a reaction to the immediate recognition of photographic reality, by making the viewer spend time looking at the painting in order to fully understand what is being depicted.

Henri Matisse also stressed the importance of the time spent by the painter, though without this necessarily being shared by the viewer [127]. In Notes of a Painter, Matisse says, ‘Underlying this succession of moments which constitutes the superficial existence of beings and things, and which is continually modifying and transforming them, one can search for a truer more essential character, which the artist will seize so that he may give to reality a more lasting interpretation’. Matisse desired to ‘reach that state of condensation of sensations which makes a painting. I might be satisfied with a work done at one sitting, but I would soon tire of it: therefore I prefer to rework it so that later I may recognise it as representative of my state of mind' [128] – uniting intuition and memory.

Similarly, Cézanne – specifically acknowledging the influence of photography – observed, ' A minute in the world's life passes! To paint it in its reality, and forget everything for that! To become that minute, to be that sensitive plate ... [to] give the image of what we see, forgetting everything that appeared before out time...' [128A].

It seems that Claude Monet also wanted the viewer to live for longer with his paintings. He began applying effects similar to those of stop-action photography with seemingly static objects by painting subjects such as Rouen Cathedral or haystacks in multiple series, showing the light effects on the same subject at different times of the day, seasons and climatic conditions [123]. These works represented an attempt to incorporate the dimension of time in the paintings [124]. At a serial exhibition of the Rouen paintings, one commentator imagined a ‘perfect equivalence of art and phenomenon – a lasting vision not of twenty, but a hundred, a thousand, a million states of the eternal cathedral in the immense cycles of the sun’ [125].

Monet himself commented, ‘One does not paint a landscape ... One paints an impression of an hour of the day’. He called this approach ‘instantaneity’. He added that these paintings acquired ‘their full value only by the comparison and succession of the whole series’ [126]. In a sense, Monet is presenting history, not traditionally as a representation of the past, but as collection of representations of the evolving ‘now’. This can also be seen as a reaction to the immediate recognition of photographic reality, by making the viewer spend time looking at the painting in order to fully understand what is being depicted.

Henri Matisse also stressed the importance of the time spent by the painter, though without this necessarily being shared by the viewer [127]. In Notes of a Painter, Matisse says, ‘Underlying this succession of moments which constitutes the superficial existence of beings and things, and which is continually modifying and transforming them, one can search for a truer more essential character, which the artist will seize so that he may give to reality a more lasting interpretation’. Matisse desired to ‘reach that state of condensation of sensations which makes a painting. I might be satisfied with a work done at one sitting, but I would soon tire of it: therefore I prefer to rework it so that later I may recognise it as representative of my state of mind' [128] – uniting intuition and memory.

Similarly, Cézanne – specifically acknowledging the influence of photography – observed, ' A minute in the world's life passes! To paint it in its reality, and forget everything for that! To become that minute, to be that sensitive plate ... [to] give the image of what we see, forgetting everything that appeared before out time...' [128A].

Radical experimentation

Once the more obvious insights into ‘reality’ disclosed by photography and chronophotography had been assimilated by painters, there followed some twenty years in which the subject of time seemed to disappear as a major artistic motif. Kern suggests for example, that during this period, watches and clocks – normally familiar, orderly, measurable and reassuring presences – almost disappeared from major works of art [129]. It is almost as if the ‘old’ concept of time had been displaced, but that although this change had been recognised, painters still needed time to assimilate the additional visual insights into the way that time could be fragmented and manipulated.

When this assimilation finally occurs, it does so in a radical new way. The Cubist works of Picasso and Braque that emerged from 1906 onwards fractured the image, just as chronophotography or train journeys had, and as movie editing was starting to do. But they then confounded viewers by presenting the resultant multiple perspectives – or discontinuities of perspective – in the one painting. This was initially believed to represent the passage of time by presenting various aspects of the subject at different times [130]. However, it seems more accurate to say that the various facets are meant to exist and be seen simultaneously by a stationary viewer [131]. In one sense, that would mean that the factor of natural time is eliminated. Either way, these works signalled that time was being conceived in an experimental manner.

Taking this further, there has been much controversy on the more specific issue of the possible relationship between Cubism and Einstein’s concept of space-time. Some commentators have denied that there is any relationship at all, some have argued that such parallels as exist are largely coincidental, some that the relationship is one of artistic prescience or precognition, and still others suggest that both Picasso and Einstein were influenced by specific earlier sources, such as Poincaré [132]. For present purposes, however, it is not necessary to resolve this specific issue – either way, time has clearly become experimental.

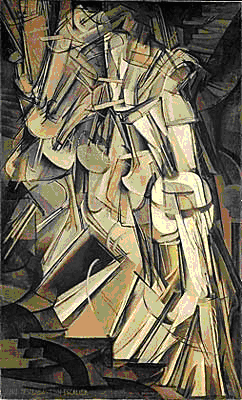

Ironically, the Cubist paintings were criticised because of their static quality – a criticism that Duchamp responded to with his equally surprising Nude Descending a Staircase (No 2) (fig 11) [133]. This work does indeed attempt to express the passage of time, but does so by presenting successive stages of the descent in a series of overlapping images, reminiscent of Marey’s photomontages (see Part 1) [133A]. Again, the extreme artificiality of the result only serves to underline the challenges that painting faced in conveying movement. Possibly acknowledging this, Duchamp introduced actual movement into art with his Bicycle Wheel (1913). His glass picture To be looked at (from the other side of the glass) with one eye, close to, for almost an hour (1918) was another ambitious attempt to convey the passage and measurement of time.

When this assimilation finally occurs, it does so in a radical new way. The Cubist works of Picasso and Braque that emerged from 1906 onwards fractured the image, just as chronophotography or train journeys had, and as movie editing was starting to do. But they then confounded viewers by presenting the resultant multiple perspectives – or discontinuities of perspective – in the one painting. This was initially believed to represent the passage of time by presenting various aspects of the subject at different times [130]. However, it seems more accurate to say that the various facets are meant to exist and be seen simultaneously by a stationary viewer [131]. In one sense, that would mean that the factor of natural time is eliminated. Either way, these works signalled that time was being conceived in an experimental manner.

Taking this further, there has been much controversy on the more specific issue of the possible relationship between Cubism and Einstein’s concept of space-time. Some commentators have denied that there is any relationship at all, some have argued that such parallels as exist are largely coincidental, some that the relationship is one of artistic prescience or precognition, and still others suggest that both Picasso and Einstein were influenced by specific earlier sources, such as Poincaré [132]. For present purposes, however, it is not necessary to resolve this specific issue – either way, time has clearly become experimental.

Ironically, the Cubist paintings were criticised because of their static quality – a criticism that Duchamp responded to with his equally surprising Nude Descending a Staircase (No 2) (fig 11) [133]. This work does indeed attempt to express the passage of time, but does so by presenting successive stages of the descent in a series of overlapping images, reminiscent of Marey’s photomontages (see Part 1) [133A]. Again, the extreme artificiality of the result only serves to underline the challenges that painting faced in conveying movement. Possibly acknowledging this, Duchamp introduced actual movement into art with his Bicycle Wheel (1913). His glass picture To be looked at (from the other side of the glass) with one eye, close to, for almost an hour (1918) was another ambitious attempt to convey the passage and measurement of time.

_ Meanwhile, the Italian futurists – the self-described ‘caffeine of Europe’ – specifically declared their own war on traditional representations of time and space, declaring that those concepts had ‘died yesterday’ [134]. Borrowing explicitly from Marey [135], the futurists declared that the form of objects ‘changes like rapid vibration, in their mad career, thus a running horse has not four legs but twenty’. Thus, some of their works, analogously with the emerging stream of consciousness novels, were intended to present the sensation of time, reflecting a ‘simultaneity of states of mind… [where] the picture must be the synthesis of what one remembers and what one sees’[136]. These works conformed to Apollinaire’s pronouncement that the painter must ‘encompass in one glance the past, the present, and the future’. So, for example, in Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash [fig 12], Balla superimposed a series of successive single instants in time on one another and squeezed them into one work.

_ At about the same time, the watches and clocks which had temporarily retreated from major art reappear in surprising new guises. In The Watch (1913), Juan Gris rotated his cubist watch at 90 degrees, and broke it into four quadrants, only two of which were visible, with the minute hand missing. Similarly, Gleizes (1913) put a clock in a cubist portrait and effaced half the numbers. In these works, painters found a more literal way to represent the new concept of fragmentation and manipulation of time [137].

The Italian de Chirico also started a series of works in which clocks and trains appear in an almost obsessional manner [137A]. This conjunction of motifs may be significant – de Chirico’s father was a railway engineer, and it is possible that de Chirico connected the railroads with the standard time that began to be imposed on a global scale in 1912 [138]. In these perversely frozen works, the clocks appear normal, but the times displayed are manipulated in a manner inconsistent with real time, as implied by the length of the shadows that form such a prominent role. For example, in The Soothsayer’s Recompense, the clock shows the time as just before 2 o’clock, but the elongated shadows are typical of those cast by an evening sun already low in the sky [139]. Another odd relationship of space and time appears in Gare Montparnasse (The melancholy of departure (1914), in which the prominent clock is contrasted with the contradictory perspectives – none of the angles of the walls, towers and arcades meet at the same point – producing a highly unstable space and unsettling experience of a new relationship between space and time [140]. De Chirico was also reputed to date paintings incorrectly, and sometimes even altered the dates after they had been hung [141].

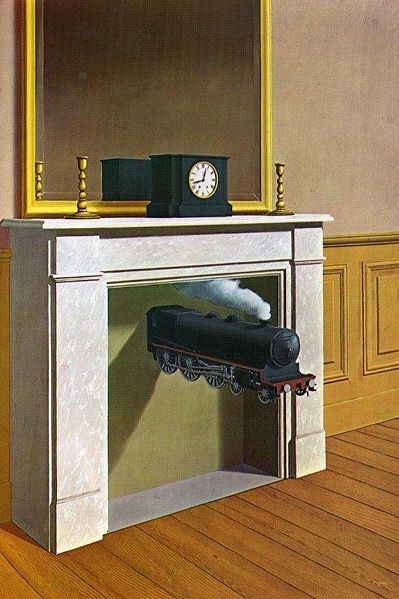

A more radical manipulation of time later appears as a prominent feature of surrealist works. So, for example, in his 1928 essay ‘Theatre in the Midst of Life’, Rene Magritte described his art as a stage on which the natural laws of time and space cease to apply [142]. Magritte was interested in de Chirico’s work, and his own Time Transfixed (1938) also features a train and a clock. Again, as with de Chirico, there is an apparent time discrepancy – the clock shows the time at a quarter to one, but there appears to be natural light casting the deeper shadows of a much later time [143]. More bizarrely, a tiny train is steaming into a room through the blocked-up fireplace, typical of the odd juxtapositions of surrealism. The painting style, a type of flat, deadpan realism, mimics photography but this only serves to heighten the surreal character of the subject matter. These ‘snapshots of the impossible, rendered in the dullest and most literal way’ [144] echo Dostoevsky’s 1860 comment that ‘the fantastic must be so close to the real that you almost have to believe in it’[145].

The Italian de Chirico also started a series of works in which clocks and trains appear in an almost obsessional manner [137A]. This conjunction of motifs may be significant – de Chirico’s father was a railway engineer, and it is possible that de Chirico connected the railroads with the standard time that began to be imposed on a global scale in 1912 [138]. In these perversely frozen works, the clocks appear normal, but the times displayed are manipulated in a manner inconsistent with real time, as implied by the length of the shadows that form such a prominent role. For example, in The Soothsayer’s Recompense, the clock shows the time as just before 2 o’clock, but the elongated shadows are typical of those cast by an evening sun already low in the sky [139]. Another odd relationship of space and time appears in Gare Montparnasse (The melancholy of departure (1914), in which the prominent clock is contrasted with the contradictory perspectives – none of the angles of the walls, towers and arcades meet at the same point – producing a highly unstable space and unsettling experience of a new relationship between space and time [140]. De Chirico was also reputed to date paintings incorrectly, and sometimes even altered the dates after they had been hung [141].

A more radical manipulation of time later appears as a prominent feature of surrealist works. So, for example, in his 1928 essay ‘Theatre in the Midst of Life’, Rene Magritte described his art as a stage on which the natural laws of time and space cease to apply [142]. Magritte was interested in de Chirico’s work, and his own Time Transfixed (1938) also features a train and a clock. Again, as with de Chirico, there is an apparent time discrepancy – the clock shows the time at a quarter to one, but there appears to be natural light casting the deeper shadows of a much later time [143]. More bizarrely, a tiny train is steaming into a room through the blocked-up fireplace, typical of the odd juxtapositions of surrealism. The painting style, a type of flat, deadpan realism, mimics photography but this only serves to heighten the surreal character of the subject matter. These ‘snapshots of the impossible, rendered in the dullest and most literal way’ [144] echo Dostoevsky’s 1860 comment that ‘the fantastic must be so close to the real that you almost have to believe in it’[145].

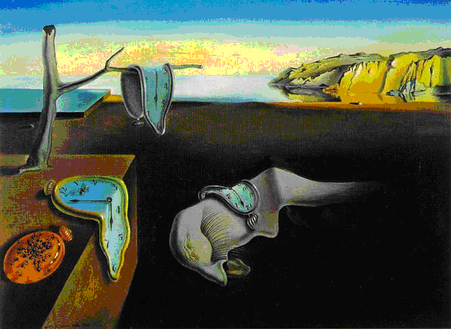

Salvador Dali introduced multiple elements of unreal time into works such as The Persistence of Memory (1931) (fig 14). This work forms an intriguing contrast with Dyce’s Recollections of Pegwell Bay (fig 8), discussed earlier. The paintings have some eerie similarities, not just in having a title that explicitly invokes memory, but also in composition and subject matter. Compositionally, both show wide flat beaches, a calm sea at low tide, in a transitional late afternoon light. Both feature a tapering line of weathered cliffs on the right, and wide band of crystalline, largely cloudless sky [146]. Both also share a preoccupation with time. But whereas Dyce’s conception, as we have seen, was largely concerned with depicting the importance of time, Dali develops this much further by showing how time can be manipulated. In various ways, Dali subverts our expectations of an orderly and predictable world. Not only are the metal watches melting, and being attacked by hour-glass ants, but each is showing a different time. Thus, both ‘normal’ time and the machines that measure it are depicted as ineffective and irrelevant [147]. The incongruity is heightened by Dali’s precise rendering of what he called his ‘hand-painted dream photograph’, in which he sought to make the unreal as real as possible. The work also reflects the effects of entropy, the ‘arrow of time’ which we have mentioned earlier (see Part 1). Thus, we see a dead tree, crumbling fossil cliffs, a fly feeding on metal as if it were rotting flesh, and a body distorted as if in death – a collection of images of objects falling apart, fossilising, crumbling, rotting or melting away [148].

Dali’s inspiration has been variously attributed to Freudian dream theory – in which the unconscious may be accessed through dreams in which time works in all directions – or to Einstein’s relativity theory. More prosaically, as Dali sometimes provocatively claimed, it has been attributed to the chance sighting of a melting over-mature camembert. Whichever applies, he is playing with time.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2018

We welcome your comments on this article

END NOTES [continued from Pt 2]

100. In once sense, all paintings – considered as artefacts –are themselves time travellers. ‘One of the jobs of a modern museum is to protect [those artefacts] from time. The aim is to carry [them] forward unaltered, like the cryogenically frozen travellers in science fiction movies’ (Sturgis, A, Telling Time, National Gallery London 2000 at 25). Considered as images they are time travellers too, as they capture the image in the artist’s mind at the point of conception and carry it forward into the future.

101. Charles Manby Smith ‘Last Post at St-Martin’s-le-Grand’, in Curiosities of London Life, 1853.

102. Website of the Liverpool Art Museum at: http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk

103. Bills, M and Knight, V, William Powell Frith – Painting the Victorian Age, Yale University Press, 2006 at 81.

103a. Turner also portrayed a similar transition in sea transport -- the passing of the age of sail and its looming replacement by steam -- in his poignant The Fighting Temeraire, Tugged To Her Last Berth To Be Broken Up (1838): see generally Willis, S, The Fighting Temeraire, Legend of Trafalgar, Quercus, London, 2009 ch 10.

104. Many Romantic artists were indifferent or even hostile to the new technology represented by the railways. As to whether Turner was regretting or celebrating the change, contrast Daniels, S, ‘Turner and the Circulation of State in his Fields of Vision: Landscape Imagery and National Identity in England and the United States, Princeton, 1993; and Gage, J, Turner: Rain, Steam and Speed , Allen Lane, The Penguin Press, London, 1972. Ruskin, a champion of Turner, completely ignored this painting and stated that travelling by railway was not real travel, but was like being sent to a place, like a parcel. This is reminiscent of the criticism of photography that it was not real painting, but more like a mechanical copy of the world (Wilton, A, Turner in his Time, Thames and Hudson, London, 2006 at 210).

Ruskin also memorably likened rail travel to "screaming along at the tail of a big tea kettle" (quoted in Flanders, J, Circle of Sisters,. Viking, London, 2001 at 127).

105. There is a similar blurring in other works on similar themes, for example Adolph von Menzel’s The Berlin-Potsdam Railway (1847). That work, too, depicts a train travelling at full steam out of the picture frame at an angle towards the viewer.

106. Review by William Makepeace Thackeray in Fraser’s Magazine, June 1844, cited in Wilton at 210..

107. Schama, S, Landscape and Memory, Fontana Press, London, 1996 at 362. It is interesting that Einstein often used the concept of a speeding train as a device in explaining the concept of space-time.

108. Spate, op cit, at 102.

109. House, op cit, at 196. Of course, it is always just possible that Monet simply liked sitting out in the sunshine painting trains.

109a. See Marcia Pointon, "The Representation of Time in Painting: A Study of William Dyce's Pegwell Bay: A Recollection of October 5th, 1858", Art History, I, March 1978, at 99-103.

110. This was Donati’s comet, which was at its brightest on the particular October day depicted in the painting. This comet was the second brightest in the nineteenth century, and was the first to be photographed.

111. This elegiac tone is also reflected in Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach (1867) which could almost be describing Dyce’s feelings expressed in the painting:

The sea of faith /Was once, too, at the full and round earth’s shore / Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furl’d;/ But now I only hear / Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,/ Retreating to the breath / Of the night-wind down the vast edges drear/And naked shingles of the world.

112. Lewis-Williams, D, The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art, Thames and Hudson, London, 2002 at 19, 26. It is no coincidence that it was also about this time that the discipline of art history developed.

113. Scharf, A, Art and Photography, Allen Lane, London, 1986 at 206.

114. Vaizey, M, The Artist as Photographer, Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1982 at 26; R Solnit, Motion Studies: Time, Space and Eadweard Muybridge, Bloomsbury, 2003.

115. Perhaps not so odd, really, as it was also based on a wax model (Vaizey, op cit, at 27).

116. Maas, J, Victorian Painters, Barrie and Jenkins, London, 1978 revd edn at 207. Similarly, Meissonnier’s Friedland, 1807 (1875) is a full pelt cavalry charge frozen in time, every bunched muscle and flying hoof captured with an unlikely precision (King, R, The Judgment of Paris, Walter & Co, New York, 2006 at 345). Scharf claims that Degas also made similar corrections to his horses but, to my eye, the pre-Muybridge style depicted in Carriage at the Races (1870) is repeated post-Muybridge with the horse in the left background in Racehorses (1888). Scharf also argues, less convincingly, that it is ‘more than fortuitous’ that Degas’ Scene de Ballet (1879), which shows dancers with legs completely off the ground, appeared at exactly the time Muybridge’s photos were being published in Paris (Scharf, op cit, at 205).

117. However, these effects have also been attributed to the influence of Japanese prints, which had recently started appearing in Paris (Berger, K, Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse, CUP, Cambridge 1992, at 56). It is also arguable that Degas’ so-called ‘Kodak eye’ may have been operating even without the direct influence of photography. Degas himself noted his predilection to ‘want to look through the keyhole’, an attitude likely to produce voyeur-like perspectives which could result in precisely the sharply angled viewpoints, unexpected juxtapositions, and abrupt cutting off of forms that characterised some of his art (See also Rubin, J, Impressionism and the Modern Landscape, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2008 at 47).

118. Eggum, A (transl Holm, B), Munch and Photography, Yale University Press, New Haven/London, 1989.at 157.Of course, this is not to say that before photography artists were not aware of the perceptual blurring created by movement. For example, the blurring effect caused by a rapidly spinning wheel is clearly evident in Velasquez’ The Spinners, painted back in 1648. However, in a photograph this is effect made much more explicit because it is a fixed image.

119. Scharf, op cit, at 168. The critic Louis Leroy rather uncharitably attacked this painting for its representation of figures on the street as ‘black tongue-lickings’ (Rubin at 45).

120. Varnedoe, K, ‘The Artifice of Candour: Impressionism and Photography Reconsidered’ in Art in America, January 1980, at 70. Incidentally, the quasi Impressionist blurring effect seen in modern reproductions of Niepce’s original heliograph (View from the Window at Le Gras, ca 1826) is misleading – this effect is actually due to the reproduction process and is not present in the original.

121. Bataille, G, Manet, Skira/Rizzoli, New York, 1984, at 64.

122. McClain, J, ‘Time in the Visual Arts: Lessing and Modern Criticism’, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol 44 No 1 (Autumn 1985) 41 at 46.

123. Apart from this possible theoretical inspiration for his works, Monet also used photographs as actual working aid in his series of paintings of the light effects on Rouen Cathedral. Spate recounts how Monet would venture out with a group of children, each carrying canvases representing the same subject at different times of the day. Monet then worked on the canvases and put them aside by turn, according to changes in the sky and shadows (Spate, V, Claude Monet: The Colour of Time,Thames and Hudson, London, 1992 at 230).

124. Kosinski, D, (ed) The Artist and the Camera: Degas to Picasso, Dallas Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2000 at 31. In one sense, these series paintings represent an extreme development of the traditional depiction of the four seasons (such as the Limbourg Brothers's Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c 1416)), or the past, present and the future (such as Titian's Allegory of Prudence (c 1660-1670). During the nineteenth century, Millet revived this tradition in works such as The Four Times of Day and The Four Seasons. Johnson suggests that Millet was influenced by Japanese woodblock series such as 100 Views of Famous Places in Edo (Johnson, D, ‘Confluence and Influence: Photography and the Japanese Print in 1850’, in K. S. Champa (ed) The Rise of Landscape Painting in France: Corot to Monet, Manchester N.H, Currier Gallery of Art, 1991 at 94). However, unlike Monet’s series, these depict different subject matters, whereas the whole point of Monet’s series was to depict ostensibly the same subject matter.

125. Spate, op cit, at 171.

126. House, op cit, at 197.

127. Ades, op cit, at 203.

128. Matisse, H, Notes of a Painter, at 36-37. In this respect Matisse is presumably influenced by Bergson

128A. Cited in Berger, J, Ways of Seeing, BBC/Penguin Books, London, 1972 at 31.

129. Kern, op cit, at 22, 23. Chagall is an exception to this.

130. Kern, op cit, at 22.

131. Leibowitz, op cit, at 109. It is interesting to contrast this with sixteenth century works which had anamorphic features, such the ‘distorted’ skull in Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533). These can only be fully appreciated by the viewer’s shifting their own perspective.

132. For examples of these views, see Richardson (no connection) in Shlain, op cit at 200; Liebowitz (coincidental); Schlain (precognition); and Miller (Poincaré)

133. His use of cubist imagery in this painting prompted the critic Julian Street to call it ‘an explosion in a shingle factory’, though one would have to say it was a very planned and orderly explosion. Duchamp was a great advocate of the fourth dimension in the art world (Henderson, L.D, The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidian Geometry in Modern Art, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1983 at 162). Oddly, the seemingly-radical Nude Descending has strong echoes of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones' The Golden Stairs (1880).

133A. It also serves to remind us of a far older method of conveying the passing of time -- by having the one painting depict a sequence of discrete events that happen over a period of time. So for example, in The Meeting of St Anthony and St Paul (1435), we see St Anthony walking along the road at top left of the painting, later having a chat with a centaur on the right of the painting, then finally meeting up with St Paul in the foreground.

134. The Futurist Manifesto (1909).

135. Hughes (Shock), op cit, at 44. Some of Balla’s paintings were almost literal transcriptions of the photographs.

136. Ottinger, D (ed), Futurism, Exh Cat, Tate Publishing, London 2009 at 49; Kern, op cit at 85.

137. Kern, op cit, at 23.

137A. Clocks also appear as a recurring motif in Marc Chagall’s works, typically flying –- memorably in Time is a River Without Banks (1930-39)). However, in this case, it seems that clocks are essentially still being used in their traditional way, to express the natural passage of time, and nostalgia for the old eternal values (Wullschlager, J, Chagall: Love and Exile, Allen Lane, London, 2008, at 371) Their unreal defiance of gravity simply mirrors a similar propensity by many other objects in Chagall’s work, rather than any specific distortion of the concept of time itself. In this sense Chagall’s work therefore still reflects old time, rather than the new time.

138. Kern, op cit, at 23.

139. Other examples include The Enigma of the Hour (1912), The Delights of the Poet (1913, The Philosophers Conquest (1914) and Gare Montparnasse (The Melancholy of Departure) (1914).

140. Ades, op cit, at 205.

141. De Chirico is reputed to have backdated some of his later works to take advantage of the stronger market for his early works.

142. Klingsohr-Leroy, C, Surrealism, Taschen, Koln, 2009 at 66.

143. Various versions of The Empire of Light in the 1950s create a de Chirico-like confusion of time periods by combining daylight skies with a night-time landscape.

144. Hughes, R, Nothing if not Critical, The Harvill Press, London, 1995 at 155.

145. Quoted in Linner, S, Dostoevsky on Realism, Almquick & Wiksell, Stockholm, 1967 at 178.

146. Arguably, both also contain self portraits – Dali’s in the misshapen shape in the foreground, Dyce’s on the far right, carrying artists’ materials.

147. The beaches, too, in both paintings may be evocative of the ‘sands of time’.

148. Malt, J, Obscure Objects of Desire: Surrealism, Fetishism and Politics, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004 at 193. This possibly symbolises the collapse of the fixed ‘clockwork’ cosmic order (Ades, D, Dali, Thames and Hudson, London, 1982 at 145). Significantly, Dali later revisited this work with his Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (1954), showing his earlier famous work systematically fragmenting into smaller component elements.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015

Citation: Philip McCouat, "Art in a Speeded up World", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2018

We welcome your comments on this article

END NOTES [continued from Pt 2]

100. In once sense, all paintings – considered as artefacts –are themselves time travellers. ‘One of the jobs of a modern museum is to protect [those artefacts] from time. The aim is to carry [them] forward unaltered, like the cryogenically frozen travellers in science fiction movies’ (Sturgis, A, Telling Time, National Gallery London 2000 at 25). Considered as images they are time travellers too, as they capture the image in the artist’s mind at the point of conception and carry it forward into the future.

101. Charles Manby Smith ‘Last Post at St-Martin’s-le-Grand’, in Curiosities of London Life, 1853.

102. Website of the Liverpool Art Museum at: http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk

103. Bills, M and Knight, V, William Powell Frith – Painting the Victorian Age, Yale University Press, 2006 at 81.

103a. Turner also portrayed a similar transition in sea transport -- the passing of the age of sail and its looming replacement by steam -- in his poignant The Fighting Temeraire, Tugged To Her Last Berth To Be Broken Up (1838): see generally Willis, S, The Fighting Temeraire, Legend of Trafalgar, Quercus, London, 2009 ch 10.

104. Many Romantic artists were indifferent or even hostile to the new technology represented by the railways. As to whether Turner was regretting or celebrating the change, contrast Daniels, S, ‘Turner and the Circulation of State in his Fields of Vision: Landscape Imagery and National Identity in England and the United States, Princeton, 1993; and Gage, J, Turner: Rain, Steam and Speed , Allen Lane, The Penguin Press, London, 1972. Ruskin, a champion of Turner, completely ignored this painting and stated that travelling by railway was not real travel, but was like being sent to a place, like a parcel. This is reminiscent of the criticism of photography that it was not real painting, but more like a mechanical copy of the world (Wilton, A, Turner in his Time, Thames and Hudson, London, 2006 at 210).

Ruskin also memorably likened rail travel to "screaming along at the tail of a big tea kettle" (quoted in Flanders, J, Circle of Sisters,. Viking, London, 2001 at 127).

105. There is a similar blurring in other works on similar themes, for example Adolph von Menzel’s The Berlin-Potsdam Railway (1847). That work, too, depicts a train travelling at full steam out of the picture frame at an angle towards the viewer.

106. Review by William Makepeace Thackeray in Fraser’s Magazine, June 1844, cited in Wilton at 210..

107. Schama, S, Landscape and Memory, Fontana Press, London, 1996 at 362. It is interesting that Einstein often used the concept of a speeding train as a device in explaining the concept of space-time.

108. Spate, op cit, at 102.

109. House, op cit, at 196. Of course, it is always just possible that Monet simply liked sitting out in the sunshine painting trains.

109a. See Marcia Pointon, "The Representation of Time in Painting: A Study of William Dyce's Pegwell Bay: A Recollection of October 5th, 1858", Art History, I, March 1978, at 99-103.

110. This was Donati’s comet, which was at its brightest on the particular October day depicted in the painting. This comet was the second brightest in the nineteenth century, and was the first to be photographed.

111. This elegiac tone is also reflected in Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach (1867) which could almost be describing Dyce’s feelings expressed in the painting:

The sea of faith /Was once, too, at the full and round earth’s shore / Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furl’d;/ But now I only hear / Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,/ Retreating to the breath / Of the night-wind down the vast edges drear/And naked shingles of the world.

112. Lewis-Williams, D, The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art, Thames and Hudson, London, 2002 at 19, 26. It is no coincidence that it was also about this time that the discipline of art history developed.

113. Scharf, A, Art and Photography, Allen Lane, London, 1986 at 206.

114. Vaizey, M, The Artist as Photographer, Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1982 at 26; R Solnit, Motion Studies: Time, Space and Eadweard Muybridge, Bloomsbury, 2003.

115. Perhaps not so odd, really, as it was also based on a wax model (Vaizey, op cit, at 27).

116. Maas, J, Victorian Painters, Barrie and Jenkins, London, 1978 revd edn at 207. Similarly, Meissonnier’s Friedland, 1807 (1875) is a full pelt cavalry charge frozen in time, every bunched muscle and flying hoof captured with an unlikely precision (King, R, The Judgment of Paris, Walter & Co, New York, 2006 at 345). Scharf claims that Degas also made similar corrections to his horses but, to my eye, the pre-Muybridge style depicted in Carriage at the Races (1870) is repeated post-Muybridge with the horse in the left background in Racehorses (1888). Scharf also argues, less convincingly, that it is ‘more than fortuitous’ that Degas’ Scene de Ballet (1879), which shows dancers with legs completely off the ground, appeared at exactly the time Muybridge’s photos were being published in Paris (Scharf, op cit, at 205).

117. However, these effects have also been attributed to the influence of Japanese prints, which had recently started appearing in Paris (Berger, K, Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse, CUP, Cambridge 1992, at 56). It is also arguable that Degas’ so-called ‘Kodak eye’ may have been operating even without the direct influence of photography. Degas himself noted his predilection to ‘want to look through the keyhole’, an attitude likely to produce voyeur-like perspectives which could result in precisely the sharply angled viewpoints, unexpected juxtapositions, and abrupt cutting off of forms that characterised some of his art (See also Rubin, J, Impressionism and the Modern Landscape, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2008 at 47).

118. Eggum, A (transl Holm, B), Munch and Photography, Yale University Press, New Haven/London, 1989.at 157.Of course, this is not to say that before photography artists were not aware of the perceptual blurring created by movement. For example, the blurring effect caused by a rapidly spinning wheel is clearly evident in Velasquez’ The Spinners, painted back in 1648. However, in a photograph this is effect made much more explicit because it is a fixed image.

119. Scharf, op cit, at 168. The critic Louis Leroy rather uncharitably attacked this painting for its representation of figures on the street as ‘black tongue-lickings’ (Rubin at 45).

120. Varnedoe, K, ‘The Artifice of Candour: Impressionism and Photography Reconsidered’ in Art in America, January 1980, at 70. Incidentally, the quasi Impressionist blurring effect seen in modern reproductions of Niepce’s original heliograph (View from the Window at Le Gras, ca 1826) is misleading – this effect is actually due to the reproduction process and is not present in the original.

121. Bataille, G, Manet, Skira/Rizzoli, New York, 1984, at 64.

122. McClain, J, ‘Time in the Visual Arts: Lessing and Modern Criticism’, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol 44 No 1 (Autumn 1985) 41 at 46.

123. Apart from this possible theoretical inspiration for his works, Monet also used photographs as actual working aid in his series of paintings of the light effects on Rouen Cathedral. Spate recounts how Monet would venture out with a group of children, each carrying canvases representing the same subject at different times of the day. Monet then worked on the canvases and put them aside by turn, according to changes in the sky and shadows (Spate, V, Claude Monet: The Colour of Time,Thames and Hudson, London, 1992 at 230).

124. Kosinski, D, (ed) The Artist and the Camera: Degas to Picasso, Dallas Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2000 at 31. In one sense, these series paintings represent an extreme development of the traditional depiction of the four seasons (such as the Limbourg Brothers's Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c 1416)), or the past, present and the future (such as Titian's Allegory of Prudence (c 1660-1670). During the nineteenth century, Millet revived this tradition in works such as The Four Times of Day and The Four Seasons. Johnson suggests that Millet was influenced by Japanese woodblock series such as 100 Views of Famous Places in Edo (Johnson, D, ‘Confluence and Influence: Photography and the Japanese Print in 1850’, in K. S. Champa (ed) The Rise of Landscape Painting in France: Corot to Monet, Manchester N.H, Currier Gallery of Art, 1991 at 94). However, unlike Monet’s series, these depict different subject matters, whereas the whole point of Monet’s series was to depict ostensibly the same subject matter.

125. Spate, op cit, at 171.

126. House, op cit, at 197.

127. Ades, op cit, at 203.

128. Matisse, H, Notes of a Painter, at 36-37. In this respect Matisse is presumably influenced by Bergson

128A. Cited in Berger, J, Ways of Seeing, BBC/Penguin Books, London, 1972 at 31.

129. Kern, op cit, at 22, 23. Chagall is an exception to this.

130. Kern, op cit, at 22.

131. Leibowitz, op cit, at 109. It is interesting to contrast this with sixteenth century works which had anamorphic features, such the ‘distorted’ skull in Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533). These can only be fully appreciated by the viewer’s shifting their own perspective.

132. For examples of these views, see Richardson (no connection) in Shlain, op cit at 200; Liebowitz (coincidental); Schlain (precognition); and Miller (Poincaré)

133. His use of cubist imagery in this painting prompted the critic Julian Street to call it ‘an explosion in a shingle factory’, though one would have to say it was a very planned and orderly explosion. Duchamp was a great advocate of the fourth dimension in the art world (Henderson, L.D, The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidian Geometry in Modern Art, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1983 at 162). Oddly, the seemingly-radical Nude Descending has strong echoes of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones' The Golden Stairs (1880).

133A. It also serves to remind us of a far older method of conveying the passing of time -- by having the one painting depict a sequence of discrete events that happen over a period of time. So for example, in The Meeting of St Anthony and St Paul (1435), we see St Anthony walking along the road at top left of the painting, later having a chat with a centaur on the right of the painting, then finally meeting up with St Paul in the foreground.

134. The Futurist Manifesto (1909).

135. Hughes (Shock), op cit, at 44. Some of Balla’s paintings were almost literal transcriptions of the photographs.

136. Ottinger, D (ed), Futurism, Exh Cat, Tate Publishing, London 2009 at 49; Kern, op cit at 85.

137. Kern, op cit, at 23.

137A. Clocks also appear as a recurring motif in Marc Chagall’s works, typically flying –- memorably in Time is a River Without Banks (1930-39)). However, in this case, it seems that clocks are essentially still being used in their traditional way, to express the natural passage of time, and nostalgia for the old eternal values (Wullschlager, J, Chagall: Love and Exile, Allen Lane, London, 2008, at 371) Their unreal defiance of gravity simply mirrors a similar propensity by many other objects in Chagall’s work, rather than any specific distortion of the concept of time itself. In this sense Chagall’s work therefore still reflects old time, rather than the new time.

138. Kern, op cit, at 23.

139. Other examples include The Enigma of the Hour (1912), The Delights of the Poet (1913, The Philosophers Conquest (1914) and Gare Montparnasse (The Melancholy of Departure) (1914).

140. Ades, op cit, at 205.

141. De Chirico is reputed to have backdated some of his later works to take advantage of the stronger market for his early works.

142. Klingsohr-Leroy, C, Surrealism, Taschen, Koln, 2009 at 66.

143. Various versions of The Empire of Light in the 1950s create a de Chirico-like confusion of time periods by combining daylight skies with a night-time landscape.

144. Hughes, R, Nothing if not Critical, The Harvill Press, London, 1995 at 155.

145. Quoted in Linner, S, Dostoevsky on Realism, Almquick & Wiksell, Stockholm, 1967 at 178.

146. Arguably, both also contain self portraits – Dali’s in the misshapen shape in the foreground, Dyce’s on the far right, carrying artists’ materials.

147. The beaches, too, in both paintings may be evocative of the ‘sands of time’.

148. Malt, J, Obscure Objects of Desire: Surrealism, Fetishism and Politics, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004 at 193. This possibly symbolises the collapse of the fixed ‘clockwork’ cosmic order (Ades, D, Dali, Thames and Hudson, London, 1982 at 145). Significantly, Dali later revisited this work with his Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (1954), showing his earlier famous work systematically fragmenting into smaller component elements.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015

Citation: Philip McCouat, "Art in a Speeded up World", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home

_

___