The rescue of the fabulous lost library of Deir al-Surian

The hidden benefits of being lost

On the morning of 29 December 1935, the French writer and pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry took off from Paris en route to Cochin-China, as a participant in the long-distance Paris-to-Saigon air race. That night, flying towards Casablanca across the dark vastness of the Sahara Desert, with no landmarks, he got lost and crashed. Although the crash site was not far from the isolated ancient monastery settlement of Wadi el-Natrun, it was four days before the parched and ravenous St Exupéry and his co-pilot, exhausted and delusional, would finally be rescued by Bedouin tribesmen [1].

|

For Saint-Exupéry, it must have seemed like an all-time low – out of the air race, physically and mentally depleted, and with his plane a wreck. But at least he was alive, and the incident would later pay substantial dividends – it would form the basis of his famous book Wind Sand and Stars, and inspire his classic The Little Prince, later voted as the best novel of the 20th century in France.

In retrospect, getting lost was probably the best thing that could have happened to him. |

More articles on Egypt

|

Strangely enough, in a quite different context, Wadi el-Natrun itself – and, in particular, its legendary library – would also come to experience the benefits of getting lost. In this case, those benefits would turn out to be virtually priceless. To understand why, we have to backtrack, quite a few millennia.

An ancient Egyptian past

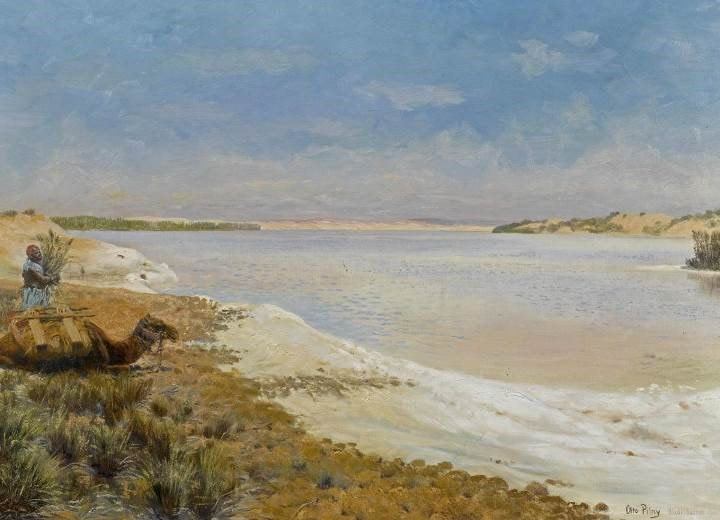

Nowadays, Wadi el-Natrun has been nominated for status as a World Heritage site [2] and is quite easily accessible – you will eventually come upon it if you travel from Cairo, into the great Western Desert, and head towards the Mediterranean seaport of Alexandria.

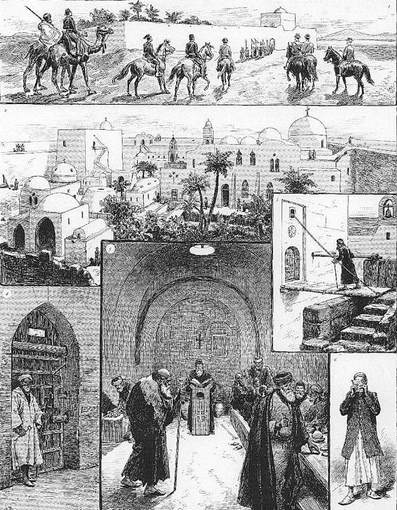

It’s best known now as a destination for travellers wishing to see the four stunning Coptic Christian monasteries, the only survivors of dozens that were built as part of a Christian settlement at the Wadi dating back to the 4th century -- St Macarius, St Pshoi, the Monastery of the Romans and the Monastery of the Syrians [3].

As old as these buildings are, however, the human history of the Wadi goes back even further, in fact over 4,000 years, to the ancient Egyptians. Back then, the Wadi was one of the principal sources of “natron”, the salt which gives the Wadi its name [4]. This natron occurs in solution in a number of seasonal alkaline lakes dotted round the surrounding desert, fed from an underground water table that stretches from the Nile Delta, where the Nile reaches the Mediterranean. These lakes dry out during summer, leaving white evaporitic deposits of natron forming a crust around their edges and in deposits on their bottom [5].

For the ancient Egyptians, and later the Romans, natron was a precious commodity. It was used to make glass and ceramics, as a soldering agent, medicines, soap and cleaning, toothpaste, mouthwash and food preservative. In addition, as we have discussed elsewhere, the Egyptians used natron as an ingredient in the creation of a blue pigment that was used extensively in Egyptian art (see our article on Egyptian Blue). Even more importantly, natron’s most prominent use was in the process of mummification, a central aspect of Egyptian religious practice, as detailed in our article on Mummy Brown. This central role in both business and cultural life led to the Wadi being known to the Egyptians as the “Field of Salt” and becoming part of a major trade route [6].

A desert sanctuary for early Christians

So how did The Wadi evolve from this into an important Christian site? According to Coptic tradition, the connection of Christianity to the site began when the Holy Family – Jesus, Mary and Joseph – stopped there for safe haven during their Flight into Egypt. Subsequently, around 330 AD, Saint Macarius of Egypt, also seeking a form of haven, went to the Wadi and established a solitary monastic site.

|

His reputation attracted a loose band of anchorites, hermits and monks who settled nearby in individual cells, intent on achieving a stoic self-discipline by enduring the privations and isolation of the desert [7].

By the end of the fourth century, distinct communities began to develop, and over time; small hermitages or monasteries – basically churches surrounded by the often-underground cells of the monks -- started to develop, eventually building up to possibly 200 in the area. |

The rise of the Syrian Monastery

Our particular area of interest here is the Syrian Monastery (Deir al-Surian, formerly Monastery of the Holy Virgin), one of the four monasteries that have survived to present times. It originally emerged in the 6th century, following a theological dispute and, later, Syrian monks also came to live there, forming a mixed community based on the common theological ideas of the Coptic and Syrian Orthodox Churches.

Gradually the Monastery’s influence grew, and by the 9th century, the monastery had become a centre of learning and cultural exchange [8]. It became the home of an outstanding collection of religious art, the relics of 12 saints, including a lock of hair of St Mary Magdalene, and the 10th-century wooden “Door of Symbols” which reportedly includes within its intricately engravings a forecast of the Church’s history till the end of the world. It was also the site of the cave in which Anba Bishoi—believed in the Coptic tradition to have washed the feet of Christ—lived as an anchorite for some 35 years, and the tamarind tree which is said to have grown out of St Mar-Ephraim’s staff [8].

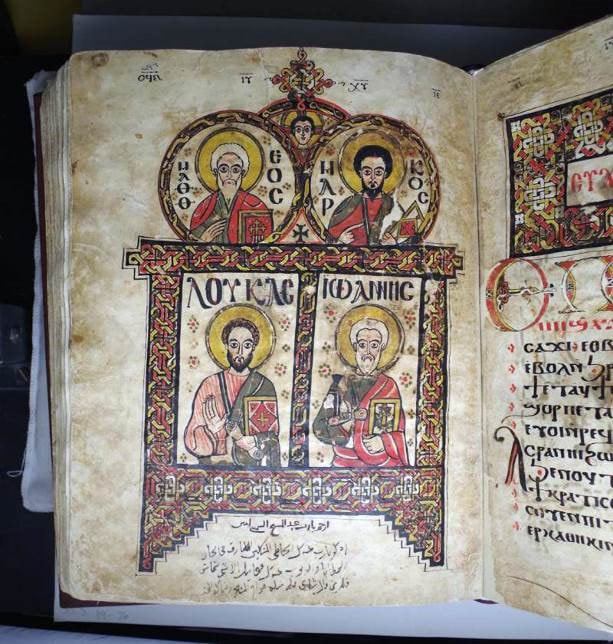

However, the Monastery’s most precious cultural possession was its almost legendary ancient library. The collection of this library evidently started quite early, and was already extensive when it was further enlarged after an extended visit by Abbot Moses to Baghdad in 927, returning with hundreds of early Syriac Manuscripts. Despite various attacks on the Wadi by desert tribes during the 5th to 9th centuries, the library grew to become the largest collection of Syriac manuscripts in the Near East. From the 11th century, further Coptic, Christian-Arabic and Ethiopic texts were added, and contributed to its reputation as one of the richest ancient libraries in Christendom [9].

Gradually the Monastery’s influence grew, and by the 9th century, the monastery had become a centre of learning and cultural exchange [8]. It became the home of an outstanding collection of religious art, the relics of 12 saints, including a lock of hair of St Mary Magdalene, and the 10th-century wooden “Door of Symbols” which reportedly includes within its intricately engravings a forecast of the Church’s history till the end of the world. It was also the site of the cave in which Anba Bishoi—believed in the Coptic tradition to have washed the feet of Christ—lived as an anchorite for some 35 years, and the tamarind tree which is said to have grown out of St Mar-Ephraim’s staff [8].

However, the Monastery’s most precious cultural possession was its almost legendary ancient library. The collection of this library evidently started quite early, and was already extensive when it was further enlarged after an extended visit by Abbot Moses to Baghdad in 927, returning with hundreds of early Syriac Manuscripts. Despite various attacks on the Wadi by desert tribes during the 5th to 9th centuries, the library grew to become the largest collection of Syriac manuscripts in the Near East. From the 11th century, further Coptic, Christian-Arabic and Ethiopic texts were added, and contributed to its reputation as one of the richest ancient libraries in Christendom [9].

Easy pickings for Western collectors

Later, however, in the 17th century, the Syrian community eventually died out, and the monastery went into a steep decline. This accelerated in the next century, as Western libraries, travellers and collectors discovered the easy pickings in the monastery’s holdings. Some of the most valuable of the manuscripts, about a thousand manuscripts, were bought or simply taken from the monks who had no idea of their value. Chief among the collectors were the Vatican, which first sent emissaries on collecting visits to the Wadi in the 18th century [10], and the British Library in the 19th century [11]. A regular antiquities trade soon developed, with manuscripts being bought in and sold by dealers in Cairo.

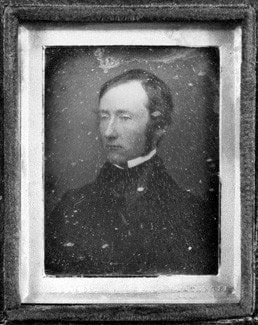

One of the collectors for the British Museum, Lord Robert Curzon, has provided this colourful first-person account of a collection visit in 1837, which gives us uncomfortable insights into the state of the Syrian Monastery’s library and Curzon’s own dubious collection methods [12]:

“In the morning [he wrote] I went to see the church and all the other wonders of the place, and on making inquiries about the library, was conducted by the old abbot, who was blind, and was constantly accompanied by another monk, into a small upper room in the great square tower, where we found several Coptic manuscripts. Most of these were lying on the floor, but some were placed in niches in the stone wall. They were all on paper, except three or four.

“One of these was a superb manuscript of the Gospels, with commentaries by the early fathers of the church; two others were doing duty as coverings to a couple of large open pots or jars, which had contained preserves, long since evaporated. I was allowed to purchase these vellum manuscripts, as they were considered to be useless by the monks, principally I believe because there were no more preserves in the jars. On the floor I found a fine Coptic and Arabic dictionary. I was aware of the existence of this volume, with which they refused to part. I placed it in one of the niches in the wall; and some years afterwards it was purchased for me by a friend, who sent it to England after it had been copied at Cairo.

“In the morning [he wrote] I went to see the church and all the other wonders of the place, and on making inquiries about the library, was conducted by the old abbot, who was blind, and was constantly accompanied by another monk, into a small upper room in the great square tower, where we found several Coptic manuscripts. Most of these were lying on the floor, but some were placed in niches in the stone wall. They were all on paper, except three or four.

“One of these was a superb manuscript of the Gospels, with commentaries by the early fathers of the church; two others were doing duty as coverings to a couple of large open pots or jars, which had contained preserves, long since evaporated. I was allowed to purchase these vellum manuscripts, as they were considered to be useless by the monks, principally I believe because there were no more preserves in the jars. On the floor I found a fine Coptic and Arabic dictionary. I was aware of the existence of this volume, with which they refused to part. I placed it in one of the niches in the wall; and some years afterwards it was purchased for me by a friend, who sent it to England after it had been copied at Cairo.

“They sold me two imperfect dictionaries, which I discovered loaded with dust upon the ground. Besides these, I did not see any other books but those of the liturgies for various holy days. These were large folios on cotton paper, most of them of considerable antiquity, and well begrimed with dirt. ….. [A]ccording to the dates contained in them, and from their general appearance, [these manuscripts] may claim to be considered among the oldest manuscripts in existence.”

Curzon suspects that there are many ancient manuscripts in the monks' oil cellar. He does not trust the blind abbot’s insistence that there are no such manuscripts, and proceeds to ply him with drink:

“The abbot, his companion, and myself sat down together. I produced a bottle of rosoglio from my stores, to which I knew that all Oriental monks were partial; for though they do not, I believe, drink wine because an excess in its indulgence is forbidden by Scripture…. and now we sat sipping our cups of the sweet pink rosoglio, and firing little compliments at each other, and talking pleasantly over our bottle till some time passed away, and the face of the blind abbot waxed bland and confiding; and he had that expression on his countenance which men wear when they are pleased with themselves and hear goodwill towards mankind in general.”

Curzon takes advantage of the situation by pretending that he is interested in the architecture of the oil cellar, and with the promise of further bottles to come, gets the access he desires:

“We then descended a narrow staircase to the oil-cellar, a handsome vaulted room, where we found a range of immense vases which formerly contained the oil, but which now on being struck returned a mournful, hollow sound. There was nothing else to be seen: there were no books here, but …. I discovered a narrow low door, and, pushing it open, entered into a small closet vaulted with stone which was filled to the depth of two feet or more with the loose leaves of the Syriac manuscripts which now form one of the chief treasures of the British Museum. Here I remained for some time turning over the leaves and digging into the mass of loose vellum pages; by which exertions I raised such a cloud of fine pungent dust that the monks relieved each other in holding our only candle at the door, while the dust made us sneeze incessantly as we turned over the scattered leaves of vellum…...”

Curzon triumphantly left the church “with a small book in the breast of my gown and a big one under each arm; and there were my servants armed to the teeth and laden with old books; and one and all we were so covered with dirt and wax from top to toe, that we looked more as if we had been up the chimney than like quiet people engaged in literary researches”.

Curzon suspects that there are many ancient manuscripts in the monks' oil cellar. He does not trust the blind abbot’s insistence that there are no such manuscripts, and proceeds to ply him with drink:

“The abbot, his companion, and myself sat down together. I produced a bottle of rosoglio from my stores, to which I knew that all Oriental monks were partial; for though they do not, I believe, drink wine because an excess in its indulgence is forbidden by Scripture…. and now we sat sipping our cups of the sweet pink rosoglio, and firing little compliments at each other, and talking pleasantly over our bottle till some time passed away, and the face of the blind abbot waxed bland and confiding; and he had that expression on his countenance which men wear when they are pleased with themselves and hear goodwill towards mankind in general.”

Curzon takes advantage of the situation by pretending that he is interested in the architecture of the oil cellar, and with the promise of further bottles to come, gets the access he desires:

“We then descended a narrow staircase to the oil-cellar, a handsome vaulted room, where we found a range of immense vases which formerly contained the oil, but which now on being struck returned a mournful, hollow sound. There was nothing else to be seen: there were no books here, but …. I discovered a narrow low door, and, pushing it open, entered into a small closet vaulted with stone which was filled to the depth of two feet or more with the loose leaves of the Syriac manuscripts which now form one of the chief treasures of the British Museum. Here I remained for some time turning over the leaves and digging into the mass of loose vellum pages; by which exertions I raised such a cloud of fine pungent dust that the monks relieved each other in holding our only candle at the door, while the dust made us sneeze incessantly as we turned over the scattered leaves of vellum…...”

Curzon triumphantly left the church “with a small book in the breast of my gown and a big one under each arm; and there were my servants armed to the teeth and laden with old books; and one and all we were so covered with dirt and wax from top to toe, that we looked more as if we had been up the chimney than like quiet people engaged in literary researches”.

rediscovery and resurrection

For the next hundred years, it seems that the library continued in a state of neglectful decline. The ancient tower, where the main cache of manuscripts was kept, was secure but nevertheless extremely unsuitable for conservation purposes – temperatures ranged from 5 to 43 degrees, and humidity from 30 to 80% [13]. The paper became brittle and discoloured, the inks faded and pages became damaged and fragmented from moisture and mishandling. The silverfish and mice had a field day.

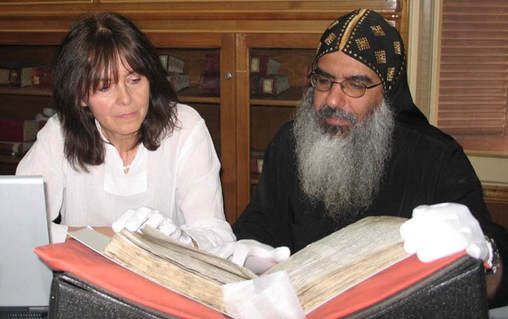

The first signs of a concentrated attempt to save the library from its slow destruction came in the mid-20th century. Coptic scholars began a process of cataloguing and relocating the contents to a better building. Nevertheless, the decline continued. The turning point finally came as recently as 1997 when Father Bigoul, who was then in charge of the library, commissioned a conservation expert to examine the manuscripts and advise on how they could be restored. The expert, London-based conservator Elizabeth Sobczynski, was appalled at what she saw, and initiated a major conservation effort, with the cooperation of major international libraries, universities and institutions.

In 2013, this major effort culminated in the relocation of the entire collection in a new two-storey purpose-built state-of-the-art library, within the existing ancient walls, which not only preserves the manuscripts but also acts as a restoration and conservation centre. It is planned that ultimately the collection will be digitised and become available online. In the meantime, a comprehensive catalogue has been published [14]. At the same time, major conservation efforts are being undertaken on the many paintings and artworks in the monasteries [15].

Highlights of the collection

Currently, the library includes some 2,000 Coptic, Arabic, Syriac, Greek and Ethiopian manuscripts which date back from the fifth to the 17th century [16]. Astonishingly, many of them are earlier than the tenth century. The oldest manuscript is part of a book which dates back to the 5th century and chronicles the lives of martyrs. The Coptic collection constitutes more than 300 manuscripts which date back from the 11th century to the 19th century. Most important among them is the oldest complete Gospel of St John in Coptic. Another significant manuscript, from the 12th-century, deals with the consecration of new churches. The biggest is a 369-page manuscript written in both Coptic and Arabic. It is reportedly the oldest version of the New Testament and was revised against Greek, Syriac, Ethiopian and Latin translations [17].

Conclusion

If it were not for Wadi el-Natrun’s isolation, the manuscripts at the Syrian Monastery may well have been lost or dispersed years ago. Yet, by the 20th century, that same isolation almost led to them being lost in any event, due to neglect or a lack of appreciation for their cultural value. Fortunately, although a massive conservation effort will still be needed, it now seems assured that this cultural treasure will be preserved for coming generations.

The Western involvement in past centuries has also proved to be rather a two-edged sword. Even in his own time, Curzon’s tactics to obtain books drew some strong criticism. One contemporary reviewer referred to the “uncomfortable impression produced in our minds by [Curzon’s] story told, with such great apparent relish… of the strong spirituous drink with which he drugged the old blind abbot into insensibility or stupidity, that so he might the better accomplish his purpose: an important purpose perhaps, but not one which ought to have been compassed by such measures as these. Indeed, whatever may be the value of the collection of Syriac MSS, now deposited in the British Museum, all religious men must feel that it is dearly purchased at the sacrifice of morality and national character” [18].

Be this as it may, the Monastery’s leader Father Bigoul is reconciled to the past losses of many of the manuscripts to Western collectors and museums. He told The Art Newspaper that the most important thing is for them to be well cared for… "When I saw the Deir al-Surian manuscripts at the British Library, I was so happy to touch books which had been written by our saintly fathers. I felt that I was meeting the people who wrote them, and it was like being reunited with my family." [19] ■

© Philip McCouat 2018. First published June 2018. This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “The rescue of the fabulous lost library of Deir al-Surian”, Journal of Art in Society” www.artinsociety.com

For more articles on Egypt, see the box at the start of this article.

The Western involvement in past centuries has also proved to be rather a two-edged sword. Even in his own time, Curzon’s tactics to obtain books drew some strong criticism. One contemporary reviewer referred to the “uncomfortable impression produced in our minds by [Curzon’s] story told, with such great apparent relish… of the strong spirituous drink with which he drugged the old blind abbot into insensibility or stupidity, that so he might the better accomplish his purpose: an important purpose perhaps, but not one which ought to have been compassed by such measures as these. Indeed, whatever may be the value of the collection of Syriac MSS, now deposited in the British Museum, all religious men must feel that it is dearly purchased at the sacrifice of morality and national character” [18].

Be this as it may, the Monastery’s leader Father Bigoul is reconciled to the past losses of many of the manuscripts to Western collectors and museums. He told The Art Newspaper that the most important thing is for them to be well cared for… "When I saw the Deir al-Surian manuscripts at the British Library, I was so happy to touch books which had been written by our saintly fathers. I felt that I was meeting the people who wrote them, and it was like being reunited with my family." [19] ■

© Philip McCouat 2018. First published June 2018. This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “The rescue of the fabulous lost library of Deir al-Surian”, Journal of Art in Society” www.artinsociety.com

For more articles on Egypt, see the box at the start of this article.

End Notes

[1] This Day in Aviation https://www.thisdayinaviation.com/30-december-1935-wind-sand-stars/, 29 December 2017

[2] https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/1827/

[3] “The Coptic Monasteries of the Wadi Natrun” https://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3252813.pdf.bannered.pdf

[4] Natron is a hydrated sodium carbonate mineral with the formula Na2CO3·10H2O. The chemical symbol for sodium, “Na”, is based on the Latin natrium.

[5] MF Sayed and MH Abdo, “Assessment of Environmental Impact on Wadi el-Natrun Depression Lakes Water, Egypt”, World Journal of Fish and Marine Sciences 1 (2) 129-136, 2009 https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9434/7d35053545e59a5fe24e1af1141273a70fc5.pdf

http://antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/shortland/shortland.html

[6] Karl-Heinz Brune, “The multiethnic character of the Wad al-Natrun”, Christianity and Monasticism in Wadi al-Natrun, American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, 2009 (ed Maged SA Mikhail and Mark Moussa), at 12, 13.

[7] Karel Innemée, “A Lifetime in Solitary: Early Hermits of the Egyptian Deserts”, Rawi Magazine, Iss 6, 2014 http://rawi-magazine.com/articles/solitary_life/

[8] Victor Salama, “The Deir Al-Surian Manuscript Library”, Watani International, 6 July 2013 http://en.wataninet.com/culture/heritage/the-deir-al-surian-manuscript-library/10517/

[9] Martin Bailey for The Art Newspaper, “Ancient Manuscripts Found in Egyptian Monastery”, Forbes, 29 May 2002 https://www.forbes.com/2002/05/29/0529conn.html#5d18f0372944; SG Richter “Wadi El Natrun and Coptic Literature” in Christianity and Monasticism in Wadi Al-Natrun, American Univ in Cairo Press, 2009 (eds Maged S. A. Mikhail and Mark Moussa, at 43ff.

[10] Teresa Levonian Cole, “Egypt’s Mysterious Monastery Hides Ancient Secrets”, Assyrian International News Agency, 7 February 2014, http://www.aina.org/ata/20140206205930.htm; Jimmy Dunn, “The Monastery of the Syrins in Wadi Natrun”, in Tour Egypt http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/surian.htm; Richter, op cit.

[11] Other foreign collectors included the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris and the St. Petersburg Library.

[12] Hon Robert Curzon. A Visit to Monasteries in the Levan , George P Putnam & Co, New York 1852 https://archive.org/stream/avisittomonaste01curzgoog/avisittomonaste01curzgoog_djvu.txt

[13] Salama, op cit; Bailey op cit

[14] E Sobczynski and M Antonia, “The new Deir al-Surian library and conservation centre”, May 2013. 20-23; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292112802_The_new_Deir_al-Surian_library_and_conservation_centre

Sebastian Brock and Lucas van Rompay, Catalogue of the Syriac Manuscripts and Fragments in the Library of Deir al-Surian, Wadi al-Natrun (Egypt), Uitgeverij Peeters, 2014.

[15] A future Journal article on this aspect is being contemplated.

[16] Salama, op cit.

[17] Salama, op cit.

[18] Review in Ecclesiologist No LXXIII August 1849 at p 2 https://books.google.com.au/books?id=eI0QAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq=visits+to+monasteries+in+the+levant+curzon&source=bl&ots=JlezPPmpCA&sig=VwjMiL_Nocb-RVllaz-gGDGMCXk&hl=en&sa=X&ei=IWjHUpeLO8aXkgWChoC4CA&ved=0CFMQ6AEwCTgK#v=onepage&q=visits%20to%20monasteries%20in%20the%20levant%20curzon&f=false

[19] Bailey, op cit.

© Philip McCouat 2018

[2] https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/1827/

[3] “The Coptic Monasteries of the Wadi Natrun” https://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3252813.pdf.bannered.pdf

[4] Natron is a hydrated sodium carbonate mineral with the formula Na2CO3·10H2O. The chemical symbol for sodium, “Na”, is based on the Latin natrium.

[5] MF Sayed and MH Abdo, “Assessment of Environmental Impact on Wadi el-Natrun Depression Lakes Water, Egypt”, World Journal of Fish and Marine Sciences 1 (2) 129-136, 2009 https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9434/7d35053545e59a5fe24e1af1141273a70fc5.pdf

http://antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/shortland/shortland.html

[6] Karl-Heinz Brune, “The multiethnic character of the Wad al-Natrun”, Christianity and Monasticism in Wadi al-Natrun, American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, 2009 (ed Maged SA Mikhail and Mark Moussa), at 12, 13.

[7] Karel Innemée, “A Lifetime in Solitary: Early Hermits of the Egyptian Deserts”, Rawi Magazine, Iss 6, 2014 http://rawi-magazine.com/articles/solitary_life/

[8] Victor Salama, “The Deir Al-Surian Manuscript Library”, Watani International, 6 July 2013 http://en.wataninet.com/culture/heritage/the-deir-al-surian-manuscript-library/10517/

[9] Martin Bailey for The Art Newspaper, “Ancient Manuscripts Found in Egyptian Monastery”, Forbes, 29 May 2002 https://www.forbes.com/2002/05/29/0529conn.html#5d18f0372944; SG Richter “Wadi El Natrun and Coptic Literature” in Christianity and Monasticism in Wadi Al-Natrun, American Univ in Cairo Press, 2009 (eds Maged S. A. Mikhail and Mark Moussa, at 43ff.

[10] Teresa Levonian Cole, “Egypt’s Mysterious Monastery Hides Ancient Secrets”, Assyrian International News Agency, 7 February 2014, http://www.aina.org/ata/20140206205930.htm; Jimmy Dunn, “The Monastery of the Syrins in Wadi Natrun”, in Tour Egypt http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/surian.htm; Richter, op cit.

[11] Other foreign collectors included the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris and the St. Petersburg Library.

[12] Hon Robert Curzon. A Visit to Monasteries in the Levan , George P Putnam & Co, New York 1852 https://archive.org/stream/avisittomonaste01curzgoog/avisittomonaste01curzgoog_djvu.txt

[13] Salama, op cit; Bailey op cit

[14] E Sobczynski and M Antonia, “The new Deir al-Surian library and conservation centre”, May 2013. 20-23; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292112802_The_new_Deir_al-Surian_library_and_conservation_centre

Sebastian Brock and Lucas van Rompay, Catalogue of the Syriac Manuscripts and Fragments in the Library of Deir al-Surian, Wadi al-Natrun (Egypt), Uitgeverij Peeters, 2014.

[15] A future Journal article on this aspect is being contemplated.

[16] Salama, op cit.

[17] Salama, op cit.

[18] Review in Ecclesiologist No LXXIII August 1849 at p 2 https://books.google.com.au/books?id=eI0QAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq=visits+to+monasteries+in+the+levant+curzon&source=bl&ots=JlezPPmpCA&sig=VwjMiL_Nocb-RVllaz-gGDGMCXk&hl=en&sa=X&ei=IWjHUpeLO8aXkgWChoC4CA&ved=0CFMQ6AEwCTgK#v=onepage&q=visits%20to%20monasteries%20in%20the%20levant%20curzon&f=false

[19] Bailey, op cit.

© Philip McCouat 2018