How one man saved the "greatest picture in the world"

Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection

By Philip McCouat For reader comments on this article see here

Resurrection in the midst of war

In the summer of 1944, in the midst of World War II, the Allies were advancing northward into Italy, gradually overcoming the defences of the occupying German forces, and seizing control of newly-liberated towns.

As part of this advance, British troops of the Royal Horse Artillery reached the hillsides overlooking the Tuscan town of Sansepolcro, near Arrezzo [1]. In accordance with orders, they then prepared to shell the town to clear it of German soldiers before advancing.

As their bombardment began, the troop commander, Lieutenant Anthony (“Tony”) Clarke, began to be assailed by doubts. As he told it in his diary [2], a question started to nag him: Why do I know the name of this town Sansepolcro?' Suddenly he remembered – a few years before, as an art-loving teenager, he had read a book containing an essay by Aldous Huxley [3], describing how he had travelled to the town, and seen there what he rather grandly described as ''the greatest picture in the world'' [4]. "We need no imagination to help us figure forth its beauty,'' Huxley wrote, "It stands there before us in entire and actual splendour".

The painting he was talking about was the monumental 15th century fresco, The Resurrection, by Piero della Francesca.

As part of this advance, British troops of the Royal Horse Artillery reached the hillsides overlooking the Tuscan town of Sansepolcro, near Arrezzo [1]. In accordance with orders, they then prepared to shell the town to clear it of German soldiers before advancing.

As their bombardment began, the troop commander, Lieutenant Anthony (“Tony”) Clarke, began to be assailed by doubts. As he told it in his diary [2], a question started to nag him: Why do I know the name of this town Sansepolcro?' Suddenly he remembered – a few years before, as an art-loving teenager, he had read a book containing an essay by Aldous Huxley [3], describing how he had travelled to the town, and seen there what he rather grandly described as ''the greatest picture in the world'' [4]. "We need no imagination to help us figure forth its beauty,'' Huxley wrote, "It stands there before us in entire and actual splendour".

The painting he was talking about was the monumental 15th century fresco, The Resurrection, by Piero della Francesca.

Clarke was stricken ~ if the bombardment continued, would he be the one responsible for destroying this apparent masterpiece? He had already seen the damage that shelling could cause, when he’d earlier passed through the devastated Monte Cassino. His dilemma was further complicated by an unconfirmed local report that the Germans had already retreated from the town. But could that report be trusted? Might Clarke be held liable for the serious offence of disobeying clear and repeated orders if he stopped firing? Could he trust the local report? Had the masterpiece already been destroyed in the preliminary bombardment? It was a difficult choice, but Clarke was eventually firm -- he told his men to cease firing [5].

As it happened, it was a fortunate decision. Militarily, because it turned out that the Germans had in fact already vacated the town, so the bombardment had not been needed in any event. And artistically, because, as would become evident the next day when the Clarke and his troops inspected the town, the precious fresco had indeed been saved from destruction.

How the painting came about

The Resurrection had originally been commissioned by Sansepolcro’s town fathers in the 1460s, to adorn a prominent wall in the town hall.

Their choice of both artist and subject matter was understandable. Piero della Francesca was the obvious choice as artist as he had been born and grown up in the town, was well-regarded, well-connected [6], and at the height of his career [7]. As for the subject matter, the town’s own name meant “holy sepulchre” in Italian – this was the stone sepulchre in which the crucified Christ had been placed, and from which he would rise three days later. According to Christian tradition, a relic of this sepulchre had been brought to the town by its founding saints in the 10th century. So, in a very real sense, the Resurrection was a symbol of the town. This was particularly resonant in the 1460s, as the city had just shortly before had its own revival when it recovered a measure of independence from Florentine rule [8].

Their choice of both artist and subject matter was understandable. Piero della Francesca was the obvious choice as artist as he had been born and grown up in the town, was well-regarded, well-connected [6], and at the height of his career [7]. As for the subject matter, the town’s own name meant “holy sepulchre” in Italian – this was the stone sepulchre in which the crucified Christ had been placed, and from which he would rise three days later. According to Christian tradition, a relic of this sepulchre had been brought to the town by its founding saints in the 10th century. So, in a very real sense, the Resurrection was a symbol of the town. This was particularly resonant in the 1460s, as the city had just shortly before had its own revival when it recovered a measure of independence from Florentine rule [8].

What’s happening in the painting

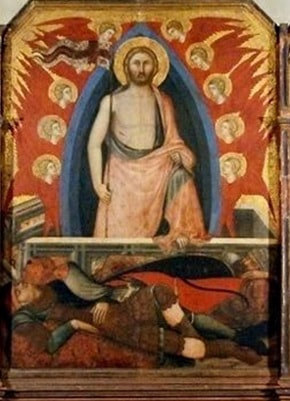

There are no Biblical accounts of the actual moment of the Resurrection, only of events before and after the Resurrection occurred. So, an artist such as Piero had nothing authoritative to follow, just the efforts of artists before him [9]. Chief among these was probably another Resurrection painted a century earlier by Niccolò de Segna, as part of the altarpiece for Sansepolcro’s nearby Cathedral (Fig 3). That painting clearly foreshadows the pyramidical or triangular composition used by Piero, with the guards slumped and sleeping below the horizontal line of the sepulchre, upon which Christ rises.

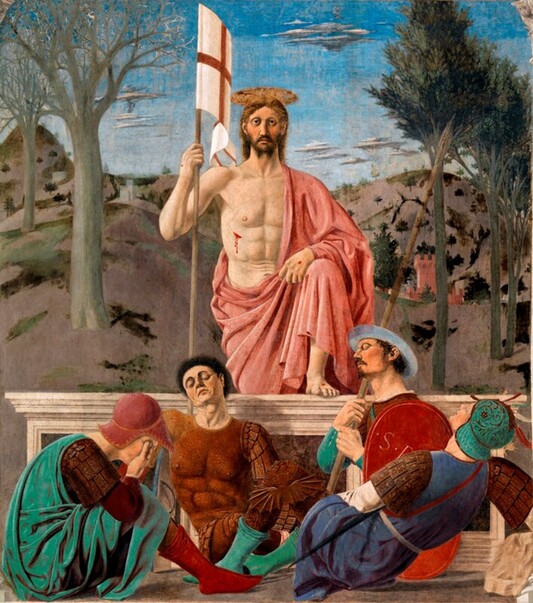

Piero painted his almost life-sized version sometime between 1460 and 1465. In his painting, which has been described as the best work he ever did [10], he depicts a pale, strongly-built Christ, muscled almost like a classical Greek hero. Rather than the expected white shroud, he is wearing a loose pinkish robe [11]. He holds a staff with a white flag adorned by a red cross – a traditional Christian symbol of the Crusaders – as he triumphantly emerges from the sepulchre in which he had been placed, one foot already resting on the top of it, looking straight ahead, seeming to stare straight at us. He seems to be challenging the viewer with the deep, dark pools of his eyes.

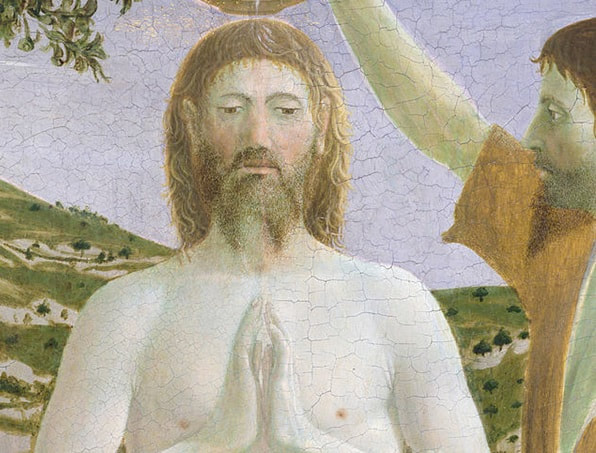

The wound in his side, previously inflicted by a Roman soldier at the Crucifixion as a “test of death”, is still actively weeping blood. His face is haggard, his wiry beard straggly in Piero’s characteristic style, with deep circles round his eyes, and his mouth is set firm. It is a face of a man who has seen life [12], who has known suffering, and who has finally prevailed. He is no “gentle Jesus, meek and mild”. His face forms a stark contrast with the innocent, almost overawed face of the younger Christ that Piero depicted in the Baptism of Christ (1650).

The wound in his side, previously inflicted by a Roman soldier at the Crucifixion as a “test of death”, is still actively weeping blood. His face is haggard, his wiry beard straggly in Piero’s characteristic style, with deep circles round his eyes, and his mouth is set firm. It is a face of a man who has seen life [12], who has known suffering, and who has finally prevailed. He is no “gentle Jesus, meek and mild”. His face forms a stark contrast with the innocent, almost overawed face of the younger Christ that Piero depicted in the Baptism of Christ (1650).

His image is spare, intense without being outwardly emotional, without a trace of the version of overdone piety that haunts so many religious paintings. No angels, no witnesses, no heavenly choruses, no miraculous source of light – Piero just gives Christ a halo to signify his holiness.

In the foreground of the painting are the Roman soldiers who were supposed to have been guarding the sepulchre against the possibility that Christ’s followers might attempt to rescue the body. The guards are fast asleep, totally unaware of the miracle that is unfolding above them – in contrast to the newly-revived Christ, they remain “dead to the world”. Their abandoned postures have been likened to a seed that has burst open [13]. and their extravagant languor contrasts sharply to the upright, stern strength of Christ. It is easy to overlook that the pose of the guard at lower right looks hardly sustainable, and the fact that the guard just beyond him does not appear to have any legs (though possibly he has just drawn up his feet underneath him) [14]. The positioning of the guard at lower left may remind us of a similar figure in Giotto’s Lamentation (Fig 5), who serves to anchor the eye and adds weight to the composition [15].

In the foreground of the painting are the Roman soldiers who were supposed to have been guarding the sepulchre against the possibility that Christ’s followers might attempt to rescue the body. The guards are fast asleep, totally unaware of the miracle that is unfolding above them – in contrast to the newly-revived Christ, they remain “dead to the world”. Their abandoned postures have been likened to a seed that has burst open [13]. and their extravagant languor contrasts sharply to the upright, stern strength of Christ. It is easy to overlook that the pose of the guard at lower right looks hardly sustainable, and the fact that the guard just beyond him does not appear to have any legs (though possibly he has just drawn up his feet underneath him) [14]. The positioning of the guard at lower left may remind us of a similar figure in Giotto’s Lamentation (Fig 5), who serves to anchor the eye and adds weight to the composition [15].

In the background, in the cool light of the first Easter morning – the birth of a new day -- are rolling hills, their shapes mimicking the shape of Christ’s shoulders. On the left, there is a suggestion of the steep hill of Golgotha and a barren winter landscape with old spindly leafless trees; on the right is a fertile land in spring, with young, verdant foliage. This is a resurrection, or rebirth, of nature itself, with the left side representing the old world and the right representing the new, into which believers may enter.

Getting a perspective on realism

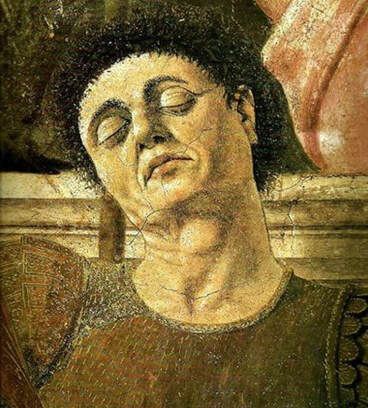

Piero was intent on increasing the realism of his painting -- if necessary by sacrificing historical accuracy -- and tried to portray the subject matter in ways that viewers could identify with. So, for example, he places the event taking place, not in Jerusalem, but in the hills of Tuscany (perhaps Sansepolcro itself). He puts the guards in contemporary 15th-century clothing rather than in Roman army uniforms (though the shield at right bears the beginning of the Roman SPQR inscription, and some are wearing a form of body armour). He even, apparently, puts his own face on one of them (Fig 6), the guard in brown who has thrown his head back to rest on the sepulchre and whose torso appears to mirror Christ’s own muscled body.

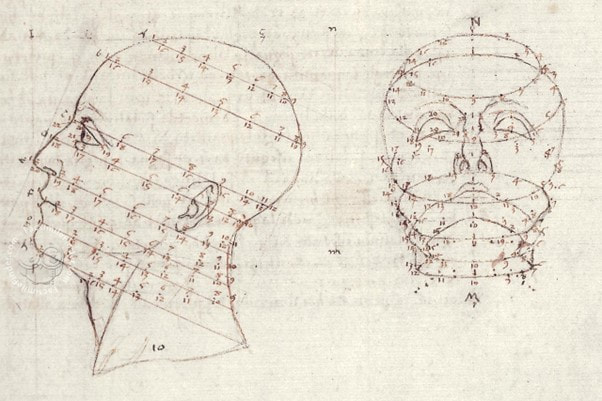

In the painting, Piero represents light in a naturalistic way, as it comes from the left and casts realistic shadows which give depth to the painting. He also makes use of other emerging skills that had been pioneered a generation before in the works of artists such as the Florentine artist Masaccio and architect Filippo Brunelleschi. During his lifetime, Piero actually became as well-known for his mathematical skills as he was for his painting. He wrote complex works about arithmetic, geometry and perspective [16], making particular use of the still-novel “Arabic” numbers. These writings were later developed by others, including Piero’s pupil Luca Pacioli, whom Vasari claims “shamefully and wickedly tried to blot out his teacher’s name and to usurp for himself the honour which belonged entirely to Piero” [17].

Piero incorporated this knowledge into his paintings. He believed that “painting is nothing but a representation of surfaces and solids foreshortened or enlarged, and put on the plane of the picture in accordance with the fashion in which the real objects seen by the eye appear on this plane” [18].

Look, for example, at the formal geometrical composition of the Resurrection, with its perfectly horizontal edge of the tomb, split in the centre by a vertical flagpole, and the equally erect posture of Christ and the nearby trees. On each side of Christ, the diagonals formed by the guards’ heads (below) and the trees (above) also serve to draw our attention to the central position of Christ [19]. Factors such as these, when added to the simplicity of Piero’s colours, and even the classical pillars at the edges of the painting, give it a monumental character, as well as conferring a sense of balance and stillness to the work.

At the same time, Piero creates the illusion of reality by making the scene appear to be three-dimensional, by introducing a vanishing point, and foreshortening nearby objects or people, such as the brown-armoured guard with his head thrown back [20]. Piero even tricks viewers of his painting by exploiting two vanishing points. If you focus at the guards, they appear to be just slightly above us, yet if we look at Christ, who is obviously much higher in the painting, he nevertheless appears to be looking straight at us.

The impact of Piero’s combination of humanism and perspective can be seen by comparing Piero’s painting with di Segna’s (Fig 3), where there is little impression of depth, the sleeping guards form just a jumble of figures, there is little structure or foreshortening, little or no feeling of natural light, a barely-evident musculature of Christ’s torso, and a background which is stylised instead of naturalistic.

Look, for example, at the formal geometrical composition of the Resurrection, with its perfectly horizontal edge of the tomb, split in the centre by a vertical flagpole, and the equally erect posture of Christ and the nearby trees. On each side of Christ, the diagonals formed by the guards’ heads (below) and the trees (above) also serve to draw our attention to the central position of Christ [19]. Factors such as these, when added to the simplicity of Piero’s colours, and even the classical pillars at the edges of the painting, give it a monumental character, as well as conferring a sense of balance and stillness to the work.

At the same time, Piero creates the illusion of reality by making the scene appear to be three-dimensional, by introducing a vanishing point, and foreshortening nearby objects or people, such as the brown-armoured guard with his head thrown back [20]. Piero even tricks viewers of his painting by exploiting two vanishing points. If you focus at the guards, they appear to be just slightly above us, yet if we look at Christ, who is obviously much higher in the painting, he nevertheless appears to be looking straight at us.

The impact of Piero’s combination of humanism and perspective can be seen by comparing Piero’s painting with di Segna’s (Fig 3), where there is little impression of depth, the sleeping guards form just a jumble of figures, there is little structure or foreshortening, little or no feeling of natural light, a barely-evident musculature of Christ’s torso, and a background which is stylised instead of naturalistic.

Multiple rescues of the painting…

The rescue of the Resurrection during the fighting of 1944 was not the first time that this painting had been saved or reborn. In fact, from the 16th to the 18th centuries it had almost been completely forgotten, due in part to the fact that for a considerable period it had disappeared under a coat of whitewash applied by workmen oblivious to its value. It was only when the whitewash started to flake off many decades later that people were reminded of its existence again.

In years since then, and even after the 1944 rescue, the painting has once again had to be saved ~ centuries of grime and humidity had resulted in it becoming flaky, cracked and discoloured to the point where it was in a desperate state of disrepair, and it was only rescued where a wealthy local businessman offered to make a significant contribution to its three-year restoration [21].

Today, the town hall that housed Piero’s Resurrection has now been converted into a museum, where the now-famous painting is its star attraction. A stylised version of the painting even appears in the town’s coat of arms, and has done so since the 16th century [22]. For a painting whose subject matter is the Resurrection, its seeming capacity for its own rebirth and renewal seems somehow fitting.

In years since then, and even after the 1944 rescue, the painting has once again had to be saved ~ centuries of grime and humidity had resulted in it becoming flaky, cracked and discoloured to the point where it was in a desperate state of disrepair, and it was only rescued where a wealthy local businessman offered to make a significant contribution to its three-year restoration [21].

Today, the town hall that housed Piero’s Resurrection has now been converted into a museum, where the now-famous painting is its star attraction. A stylised version of the painting even appears in the town’s coat of arms, and has done so since the 16th century [22]. For a painting whose subject matter is the Resurrection, its seeming capacity for its own rebirth and renewal seems somehow fitting.

...And the rescue of Piero’s reputation

The reputation of Piero has similarly had its dramatic ups and downs. Highly regarded in his lifetime, his reputation suffered after his death. There were a number of reasons for this. He mainly worked outside the major centres and his privately-commissioned works had predominantly been held, not in major museums, but in smaller or more isolated centres. Sansepolcro itself has been described as “a provincial town set far from the artistic ferment of Florence” [23] – even as late as 1925, Aldous Huxley could claim, perhaps extravagantly, that he had spent over seven hours in a bus reaching Sansepolcro, and that it was “no joke, that journey, as I know by experience” [24]. Some of his paintings were misattributed or lost or destroyed for one reason or another -- for example, frescoes he painted in the Vatican were apparently destroyed to leave room for paintings by Raphael; and rampaging French troops fired shots at his fresco series The Legend of the True Cross, in Arezzo. Fashions also changed, and his short-lived fame was swamped by later superstars such as Leonardo, Raphael and Botticelli. The increasing loss of his eyesight, and his late-life concentration on his mathematical interests, probably also cut short his artistic career [25].

It was not until the 19th and 20th centuries that Piero’s work again started receiving critical and artistic favour, even cult status, once more. While few would go as far as Huxley’s rather breathless description, Piero was enthusiastically endorsed by influential critics such as Bernard Berenson, Kenneth Clark, Roberto Longhi and Roger Fry. The New York Times art critic John Russell went so far as to say that “he is for us the first and the greatest of classical painters…He has my vote, any time, as the Perpetual President of European painting.” And art historian John Pope-Hennessy acclaimed Piero’s Flagellation of Christ as “the greatest small painting in the world” [26].

Piero’s works also appealed to those modern artists who championed the importance of inner form over outward emotion. So, for example, Giorgio de Chirico praised “the solidity, the transparency, the lyric strength of colour” of artists such as Piero [27]; Georges Seurat acknowledged Piero’s influence in his own paintings such as Bathers at Asnières (1884) and Cezanne particularly admired the geometric forms and underlying structure of Piero’s work. Even more recently, David Hockney included a partial image of Piero’s Baptism of Christ in his own work My Parents (1977), in which he acknowledges a number of his literary and artistic heroes.

It was not until the 19th and 20th centuries that Piero’s work again started receiving critical and artistic favour, even cult status, once more. While few would go as far as Huxley’s rather breathless description, Piero was enthusiastically endorsed by influential critics such as Bernard Berenson, Kenneth Clark, Roberto Longhi and Roger Fry. The New York Times art critic John Russell went so far as to say that “he is for us the first and the greatest of classical painters…He has my vote, any time, as the Perpetual President of European painting.” And art historian John Pope-Hennessy acclaimed Piero’s Flagellation of Christ as “the greatest small painting in the world” [26].

Piero’s works also appealed to those modern artists who championed the importance of inner form over outward emotion. So, for example, Giorgio de Chirico praised “the solidity, the transparency, the lyric strength of colour” of artists such as Piero [27]; Georges Seurat acknowledged Piero’s influence in his own paintings such as Bathers at Asnières (1884) and Cezanne particularly admired the geometric forms and underlying structure of Piero’s work. Even more recently, David Hockney included a partial image of Piero’s Baptism of Christ in his own work My Parents (1977), in which he acknowledges a number of his literary and artistic heroes.

Conclusions

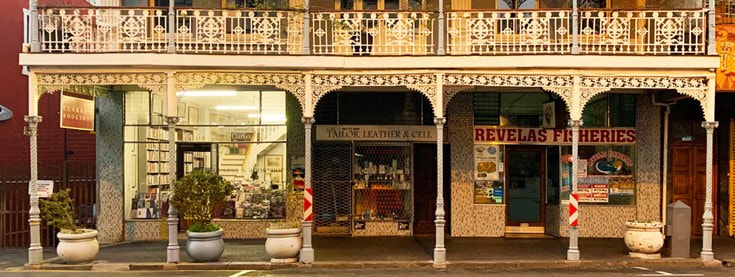

Anthony Clarke successfully survived the war, and in 1957 set up a bookshop in Cape Town, South Africa [28]. Over the years, this evolved into one of the most significant in the country; it even had its own small resurrection when Clarke’s successor had to relocate the business [29].

Meanwhile, Clarke was not forgotten by the people of Sansepolcro. In 1965 he was invited back to the town as an official guest, and was feted at a civic reception. A street in the town was even named in his honour, the Via Anthony Clarke [30]. He died in 1981.

So, what conclusions can we draw from this rather tangled tale? It could have been a story of disgrace, loss, destruction, war and death. It could have been that Clarke’s decision turned out to be disastrously wrong, that his troops faced a deadly ambush when they tried to enter the town, and that he faced a court martial for disobeying orders. It could have been, instead, that he continued the bombardment, and that the Resurrection and large parts of the town were destroyed. It could have been that the painting never emerged from its coat of whitewash. It could have been that Piero’s reputation, and the advances he made in depicting reality, slowly became forever forgotten. But none of these things happened.

So, our story is rather different -- it is one about the importance of second thoughts, the possibility of the second chance, and a reminder that hope is never quite lost.■

© Philip McCouat 2022; first published November 2022

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, "How one man saved the greatest picture in the world: Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection”, Journal of Art in Society, November 2022.

My thanks to Olga Cramsie who first told me about the story of Anthony Clarke.

Return to HOME

So, our story is rather different -- it is one about the importance of second thoughts, the possibility of the second chance, and a reminder that hope is never quite lost.■

© Philip McCouat 2022; first published November 2022

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, "How one man saved the greatest picture in the world: Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection”, Journal of Art in Society, November 2022.

My thanks to Olga Cramsie who first told me about the story of Anthony Clarke.

Return to HOME

End Notes

[1] Formerly known as Borgo San Sepolcro.

[2] Clarke’s diaries were accidently discovered, many years after his death, in a suitcase Cape Town in 2011: see Tim Butcher, “The man who saved The Resurrection”, BBC New Magazine, 24 December 2011, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-16306893

[3] Author of Brave New World (1932) and The Doors of Perception (1954), among others

[4] Aldous Huxley, “The Best Picture”, in Along the Road,(1925), at 185. Extracted at http://www.travelingintuscany.com/art/pierodellafrancesca/resurrectionhuxley.htm. Huxley’s stated reasons for this judgment are rather obscure, but he places considerable value on the painting’s “genuineness” and the fact that the artist was “genuinely noble as well as talented", bringing a quality of a natural, spontaneous and unpretentious grandeur" to the work (at 188).

[5] The story was later recounted in 1964 by author HV Morton in his A Traveller in Italy, as a result of a chance meeting with Clarke in Cape Town

[6] For a detailed treatment of his close connections with the city, see James R Banker, The Culture of San Sepolcro during the Youth of Piero della Francesca, University of Michigan Press, 2003

[7] Jeryldene Wood (ed), Cambridge Companion to Piero della Francesca, Icon, London, 1991“Introduction” at 1

[8] The large stone which we can see in the bottom right corner of the painting may actually represent that relic: see Marilyn Aronberg Levin, “Piero’s Mediation on the Nativity” in Wood, op cit at 74. A similar object appears in di Segna’s painting.

[9] For detailed treatments of Piero’s life and influences, see Bruce Cole, Piero Della Francesca: Tradition and Innovation in Form and Idiom In Renaissance Art, Westview Press, London, 1991; and Jeryldene M Wood, op cit; for an informative documentary, see BBC, The Private Life of a Masterpiece, “Piero della Francesca”, DVD Vol 1, Disc 1

[10] Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, Vol 1, Penguin Classics, London, 1987 at 194

[11] Possibly reflecting the medieval symbol of marriage, maybe the marriage of divine and human: Jonathan Baker,“The resurrection according to Matthew and Piero della Francesca” https://www.peterborough-cathedral.org.uk/157/section.aspx/156/wednesday_at_one_resurrection_in_gospel_and_art_matthew_piero_della_francesca

[12] Critic Andrew Graham Dixon describes the face as ”un-idealised, almost coarse-featured”: http://www.andrewgrahamdixon.com/archive/itp-157-the-resurrection-by-piero-della-francesca.html

[13] M B Israëls, Piero della Francesca and the Invention of the Artist, Reaktion, London, 2020 at 146

[14] Israëls, op cit at 147

[15] Christine Zappella, ”Piero della Francesca: Resurrection”, at https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/early-renaissance1/painting-in-florence/a/piero-della-francesca-resurrection

[16] Trattato d'Abaco; De Prospectiva Pingendi; and Libellus de Quinque Corporibus Regularibus: see Christopher Booker. “The mathematical revolution behind ‘the greatest picture in the world’”, The Spectator Magazine, 19 April 2014 https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-mathematical-revolution-behind-the-greatest-picture-in-the-world-

[17] Vasari, op cit at 190

[18] In Piero’s On Perspective for Painting

[19] Israëls, op cit at 146

[20] This pose is similar to various perspectives sketched by Piero in his mathematical treatises: Renana Bartal, “Piero’s Faces: Artist and Image Making in Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection of Christ”, Notes in the History of Art, Fall 2019, at 31 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335535828_Piero's_Faces_Artist_and_Image_Making_in_Piero_della_Francesca's_Resurrection_of_Christ

[21] Philip Pullella, “Spared in war, Italy’s ‘greatest picture’ saved again by benefactor”, Reuters, 16 November 2014

[22] Cole, op cit at 79

[23] Cole, op cit at 141

[24] Huxley, op cit

[25] MD Aeschiman,”The Greatest Painting”, Nation Review, 21 September 2013, https://www.nationalreview.com/2013/09/greatest-painting-m-d-aeschliman/

[26] These and additional quotes about Piero’s work are collected in Aeschliman, op cit

[27] From ‘Pro Tempera Oratio’, c. 1920

[28] Clarke’s Bookshop website https://clarkesbooks.co.za/

[29] Brent Meersman, “A bookshop’s new chapter, different setting”, Mail & Guardian (South Africa), 16 August 2013, https://mg.co.za/article/2013-08-16-new-chapter-different-setting/

[30] See generally, Fausto Braganti, “M’Accordo… when I didn’t meet Anthony Clarke”, https://biturgus.com/104a-marcordo-quando-non-ho-incontrato-anthony-clarke/

© Philip McCouat 2022

Return to HOME

[2] Clarke’s diaries were accidently discovered, many years after his death, in a suitcase Cape Town in 2011: see Tim Butcher, “The man who saved The Resurrection”, BBC New Magazine, 24 December 2011, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-16306893

[3] Author of Brave New World (1932) and The Doors of Perception (1954), among others

[4] Aldous Huxley, “The Best Picture”, in Along the Road,(1925), at 185. Extracted at http://www.travelingintuscany.com/art/pierodellafrancesca/resurrectionhuxley.htm. Huxley’s stated reasons for this judgment are rather obscure, but he places considerable value on the painting’s “genuineness” and the fact that the artist was “genuinely noble as well as talented", bringing a quality of a natural, spontaneous and unpretentious grandeur" to the work (at 188).

[5] The story was later recounted in 1964 by author HV Morton in his A Traveller in Italy, as a result of a chance meeting with Clarke in Cape Town

[6] For a detailed treatment of his close connections with the city, see James R Banker, The Culture of San Sepolcro during the Youth of Piero della Francesca, University of Michigan Press, 2003

[7] Jeryldene Wood (ed), Cambridge Companion to Piero della Francesca, Icon, London, 1991“Introduction” at 1

[8] The large stone which we can see in the bottom right corner of the painting may actually represent that relic: see Marilyn Aronberg Levin, “Piero’s Mediation on the Nativity” in Wood, op cit at 74. A similar object appears in di Segna’s painting.

[9] For detailed treatments of Piero’s life and influences, see Bruce Cole, Piero Della Francesca: Tradition and Innovation in Form and Idiom In Renaissance Art, Westview Press, London, 1991; and Jeryldene M Wood, op cit; for an informative documentary, see BBC, The Private Life of a Masterpiece, “Piero della Francesca”, DVD Vol 1, Disc 1

[10] Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, Vol 1, Penguin Classics, London, 1987 at 194

[11] Possibly reflecting the medieval symbol of marriage, maybe the marriage of divine and human: Jonathan Baker,“The resurrection according to Matthew and Piero della Francesca” https://www.peterborough-cathedral.org.uk/157/section.aspx/156/wednesday_at_one_resurrection_in_gospel_and_art_matthew_piero_della_francesca

[12] Critic Andrew Graham Dixon describes the face as ”un-idealised, almost coarse-featured”: http://www.andrewgrahamdixon.com/archive/itp-157-the-resurrection-by-piero-della-francesca.html

[13] M B Israëls, Piero della Francesca and the Invention of the Artist, Reaktion, London, 2020 at 146

[14] Israëls, op cit at 147

[15] Christine Zappella, ”Piero della Francesca: Resurrection”, at https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/early-renaissance1/painting-in-florence/a/piero-della-francesca-resurrection

[16] Trattato d'Abaco; De Prospectiva Pingendi; and Libellus de Quinque Corporibus Regularibus: see Christopher Booker. “The mathematical revolution behind ‘the greatest picture in the world’”, The Spectator Magazine, 19 April 2014 https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-mathematical-revolution-behind-the-greatest-picture-in-the-world-

[17] Vasari, op cit at 190

[18] In Piero’s On Perspective for Painting

[19] Israëls, op cit at 146

[20] This pose is similar to various perspectives sketched by Piero in his mathematical treatises: Renana Bartal, “Piero’s Faces: Artist and Image Making in Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection of Christ”, Notes in the History of Art, Fall 2019, at 31 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335535828_Piero's_Faces_Artist_and_Image_Making_in_Piero_della_Francesca's_Resurrection_of_Christ

[21] Philip Pullella, “Spared in war, Italy’s ‘greatest picture’ saved again by benefactor”, Reuters, 16 November 2014

[22] Cole, op cit at 79

[23] Cole, op cit at 141

[24] Huxley, op cit

[25] MD Aeschiman,”The Greatest Painting”, Nation Review, 21 September 2013, https://www.nationalreview.com/2013/09/greatest-painting-m-d-aeschliman/

[26] These and additional quotes about Piero’s work are collected in Aeschliman, op cit

[27] From ‘Pro Tempera Oratio’, c. 1920

[28] Clarke’s Bookshop website https://clarkesbooks.co.za/

[29] Brent Meersman, “A bookshop’s new chapter, different setting”, Mail & Guardian (South Africa), 16 August 2013, https://mg.co.za/article/2013-08-16-new-chapter-different-setting/

[30] See generally, Fausto Braganti, “M’Accordo… when I didn’t meet Anthony Clarke”, https://biturgus.com/104a-marcordo-quando-non-ho-incontrato-anthony-clarke/

© Philip McCouat 2022

Return to HOME