Vermeer’s concert, the Gardner collection, and the art heist of the century

By Philip McCouat For readers' comments on this article, see here

Introduction

In the early hours of 18 March 1990, as St Patrick’s Day revellers were still wending their way home, two men posing as police officers bluffed their way into the poorly-guarded Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston and stole 13 artworks. Despite extensive investigations by the FBI, and a massive $10 million reward being offered by the museum, the crime has never been solved, and none of the stolen works has ever been recovered.

The stolen works are an odd mixture of the highly valuable, and the not-very-valuable, of the famous and of the obscure. Their total value today is almost incalculable, certainly many hundreds of millions and, with recent soaring auction prices for famous paintings, could even be heading toward a staggering billion dollars. Fully half of that amount would be attributable to just one painting -- Jan Vermeer’s The Concert, now generally regarded as the most valuable stolen object in the world. And it is this painting – its history and its meaning – which we shall be examining in this article [1].

What’s happening in the painting

We are in a 17th century domestic parlour – possibly a room in the house owned by Vermeer’s mother-in law, which Vermeer and his family shared with her. Three well-dressed people are absorbed in creating music. The light falls mainly on the central figure, a woman, who sits, lips slightly parted, intently playing the harpsichord/clavecin – we can see its lid, painted with a peaceful pastoral scene, in the upright position. At right, a second woman stands holding sheet music, one hand raised, maybe to keep time. Between them, almost overlooked by the viewer, is a fashionably long-haired man with his back turned to us as he sits rather awkwardly on a chair. He is playing a partly-obscured lute. His bandolier/sash and sword, just visible on his left, suggest he is a member of a civic militia.

We are in a 17th century domestic parlour – possibly a room in the house owned by Vermeer’s mother-in law, which Vermeer and his family shared with her. Three well-dressed people are absorbed in creating music. The light falls mainly on the central figure, a woman, who sits, lips slightly parted, intently playing the harpsichord/clavecin – we can see its lid, painted with a peaceful pastoral scene, in the upright position. At right, a second woman stands holding sheet music, one hand raised, maybe to keep time. Between them, almost overlooked by the viewer, is a fashionably long-haired man with his back turned to us as he sits rather awkwardly on a chair. He is playing a partly-obscured lute. His bandolier/sash and sword, just visible on his left, suggest he is a member of a civic militia.

The threesome are so intent, and so close to each other, that we might even feel as if we are intruding [2]. Oddly, despite the fact that music is obviously being played, the atmosphere is still of a calm quiet. How Vermeer managed to achieve this effect in a family house with eleven noisy young children is a secret many modern-day parents would love to discover!

On the rumpled Persian carpet on the table at left is a lute and some sheet music. In the foreground, a large viola da gamba [3] lies on the foreshortened black-and-white checked marble floor – an unusually lavish type of floor for a middle class house and one probably included by Vermeer in the painting to accentuate its perspective lines.

On the rather neutral-coloured back wall are two paintings, one a landscape dominated by a large tree and luxuriant greenery, and the other a known painting, The Procuress, by Dirck van Baburen, depicting a scene in a brothel. This topic of mercenary love was one which evidently interested Vermeer -- he also used this work by van Baburen in the background of one of his other works (Lady Seated at a Virginal,1672) and Vermeer himself painted a Procuress in the early part of his career [4].

On the rumpled Persian carpet on the table at left is a lute and some sheet music. In the foreground, a large viola da gamba [3] lies on the foreshortened black-and-white checked marble floor – an unusually lavish type of floor for a middle class house and one probably included by Vermeer in the painting to accentuate its perspective lines.

On the rather neutral-coloured back wall are two paintings, one a landscape dominated by a large tree and luxuriant greenery, and the other a known painting, The Procuress, by Dirck van Baburen, depicting a scene in a brothel. This topic of mercenary love was one which evidently interested Vermeer -- he also used this work by van Baburen in the background of one of his other works (Lady Seated at a Virginal,1672) and Vermeer himself painted a Procuress in the early part of his career [4].

Does the appearance of Baburen’s work have any particular significance? It certainly seems that Vermeer sometimes chose his background artworks as oblique comments on the action taking place in the main part of the painting. Accordingly, the presence of the Baburen painting, with its obvious reference to illicit sex, has led some commentators to speculate that Vermeer is trying to contrast this with the situation of the civilised mixed-sex group sedately making music. Or he may actually have been suggesting that “beneath the quiet exteriors of the man and woman there lurk stronger passions” [5]. Then again, it also seems that the Baburen was owned by Vermeer’s mother-in-law Maria Thins [6], so it is feasible that he simply included it because it was convenient. Maybe too a combination of these facts was relevant.

As is typical for Vermeer, the painting is lit from the left, and the colours used in the painting are subdued. He carefully distributes splashes of colour and highlights throughout the scene – the silver dress and yellow sleeve of the seared woman, the orange back of the man’s chair, and white silk top of the standing woman. Light sparkles on the women’s pearls (a favourite of Vermeer) and on the white sheet music on the table.

It is striking that all the action, such as it is, takes place over on the other side of the room from the viewer. We are looking at these people as a distinct distance. In this respect, the painting resembles a movie “establishment shot”, a scene which is initially depicted at a distance so as to enable the viewers to orient themselves. In a movie, the camera would normally then focus in on what specifically is happening. But in this painting, Vermeer holds us there and, naturally, we naturally never get to any closer. The fact that we never find out what happens adds to the sense of the stillness which seems to permeate many of Vermeer’s works [7]. It also encourages us to examine every carefully-placed item in the painting to get clues as to what Vermeer’s intention may have been.

.

Vermeer’s interest in music

Scenes involving a group of people making music, such as we see in The Concert, had become a popular part of Dutch painting at the time. This reflected social life too. Music was popular among all classes in Dutch society, not only just for listening, or playing, but also for its role in facilitating social engagement and entertainment, as an accompaniment to singing and dancing [8]. Because of this role, and its association with harmony, music became particularly associated with love and courtship.

Vermeer himself was attracted to music. Young women reading letters or playing musical instruments in domestic settings appear constantly in his art. Indeed, in his The Music Lesson there is an inscription on a viola da gamba that says “Music is the companion of joy, the balm of sorrow” [9]. Perhaps that reflected Vermeer’s feelings too.

Enter Isabella Stewart Gardner

For the next step in our story, let us now jump forward to the late 1800s and early 1900s, a period in which a number of prominent women emerged as major art collectors [10]. Particularly notable among these was Isabella Stewart Gardner.

As is typical for Vermeer, the painting is lit from the left, and the colours used in the painting are subdued. He carefully distributes splashes of colour and highlights throughout the scene – the silver dress and yellow sleeve of the seared woman, the orange back of the man’s chair, and white silk top of the standing woman. Light sparkles on the women’s pearls (a favourite of Vermeer) and on the white sheet music on the table.

It is striking that all the action, such as it is, takes place over on the other side of the room from the viewer. We are looking at these people as a distinct distance. In this respect, the painting resembles a movie “establishment shot”, a scene which is initially depicted at a distance so as to enable the viewers to orient themselves. In a movie, the camera would normally then focus in on what specifically is happening. But in this painting, Vermeer holds us there and, naturally, we naturally never get to any closer. The fact that we never find out what happens adds to the sense of the stillness which seems to permeate many of Vermeer’s works [7]. It also encourages us to examine every carefully-placed item in the painting to get clues as to what Vermeer’s intention may have been.

.

Vermeer’s interest in music

Scenes involving a group of people making music, such as we see in The Concert, had become a popular part of Dutch painting at the time. This reflected social life too. Music was popular among all classes in Dutch society, not only just for listening, or playing, but also for its role in facilitating social engagement and entertainment, as an accompaniment to singing and dancing [8]. Because of this role, and its association with harmony, music became particularly associated with love and courtship.

Vermeer himself was attracted to music. Young women reading letters or playing musical instruments in domestic settings appear constantly in his art. Indeed, in his The Music Lesson there is an inscription on a viola da gamba that says “Music is the companion of joy, the balm of sorrow” [9]. Perhaps that reflected Vermeer’s feelings too.

Enter Isabella Stewart Gardner

For the next step in our story, let us now jump forward to the late 1800s and early 1900s, a period in which a number of prominent women emerged as major art collectors [10]. Particularly notable among these was Isabella Stewart Gardner.

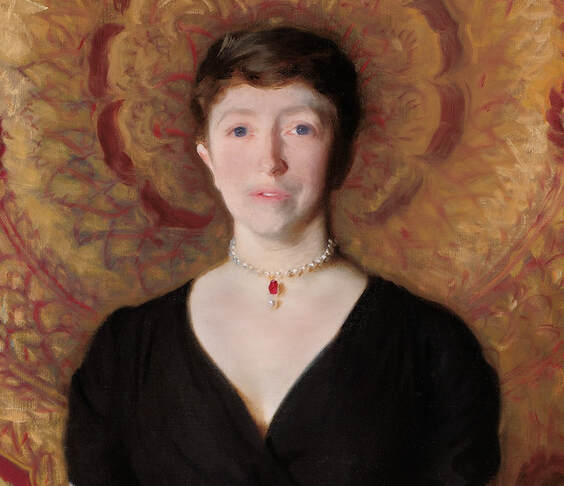

Isabella came from a rich and privileged background, was married to the wealthy Jack Gardner, and was a flamboyant, fashionable, attrractive, high-spirited and fiercely determined Boston socialite. With the nickname “Mrs Jack”, she was a person who attracted and courted publicity when it suited her, and there were numerous tales of her surprising exploits – the lion cubs she “adopted”, the “Oh, you Red Sox” headband she wore to a staid performance of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, her number of footmen, her smoking Turkish cigarettes, her posing in the nude, her hosting of dinners for winning sports teams, her habit of walking home from the opera unescorted and encrusted with jewels, her infatuations with sensitive male artists – true, exaggerated or invented, they all contributed to her aura of celebrity. Her personal motto was “C’est mon plaisir” (It is my pleasure) [11].

The Gardners had started collecting during their many trips abroad, and Isabella started making acquisitions on her own account in 1891, after inheriting a fortune from her father. She soon made her mark. In the following year, she would make the purchase which created an international stir, and heralded her arrival as a serious collector. It was the purchase of Vermeer’s The Concert.

A fateful auction

The purchase occurred at the Paris auction of the estate of Théophile Thoré-Bürger, a prominent journalist and art critic. In the 1860s, he had been instrumental in reviving the reputation of Vermeer, who had largely been forgotten in the centuries since he died in 1675 (see our article here).

The fact that The Concert had been owned by a person who had been so influential in the growing appreciation of Vermeer’s paintings no doubt added extra spice to the painting. It appeared to be a personal choice by the music-loving Gardner herself though, at the auction, she observed the social proprieties of the time by using a male agent bid on her behalf, signalling him with a wave of her handkerchief, and beating off competition from the National Gallery and the Louvre. Her winning bid was $6,000 [12]. In just one swoop, she became a major player in the international art world [13].

The Gardners had started collecting during their many trips abroad, and Isabella started making acquisitions on her own account in 1891, after inheriting a fortune from her father. She soon made her mark. In the following year, she would make the purchase which created an international stir, and heralded her arrival as a serious collector. It was the purchase of Vermeer’s The Concert.

A fateful auction

The purchase occurred at the Paris auction of the estate of Théophile Thoré-Bürger, a prominent journalist and art critic. In the 1860s, he had been instrumental in reviving the reputation of Vermeer, who had largely been forgotten in the centuries since he died in 1675 (see our article here).

The fact that The Concert had been owned by a person who had been so influential in the growing appreciation of Vermeer’s paintings no doubt added extra spice to the painting. It appeared to be a personal choice by the music-loving Gardner herself though, at the auction, she observed the social proprieties of the time by using a male agent bid on her behalf, signalling him with a wave of her handkerchief, and beating off competition from the National Gallery and the Louvre. Her winning bid was $6,000 [12]. In just one swoop, she became a major player in the international art world [13].

In choosing the paintings she wanted for her collection, Isabella took a personal approach, informed by her appreciation of their cultural and historic value, rather than merely depending on the views of agents, art experts or dealers. In general, it was their connections, not necessarily their knowledge or opinions, that appeared to have been their greatest value to her [14]. However, the prominent art conoisseur Bernard Berenson proved to be particularly helpful in many of her acquisitions.

Isabella’s main focus was on European art. Her approach, perhaps reflecting her personality, was bold and ambitious, targeting and obtaining major works by artists such as Botticelli, Rembrandt Titian, Fra Angelico, Velazquez and, as we have seen, Vermeer. The Gardners’ house, extensive as it was, soon became too crowded for the burgeoning collection and the couple turned their minds to creating their own purpose-built museum. Following Jack’s death in 1898, Isabella moved swiftly to put this into practice, purchasing land and having plans made for a new building, Fenway Court. It was modelled ambitiously on Venetian Renaissance palaces [15], based round a central courtyard (Fig 7); however, rumours that the building was being transported stone by stone from Venice were, sadly, unfounded.

Establishment of the Gardner Museum

Isabella took a deep and almost obsessive interest in the design, construction and decoration of the museum, insisting that her exact wishes, and no-one else’s, must be followed, even in the smallest of details [16]. She forged ahead with the project, ignoring dissenting views, never even bothering to lodge development plans, or to get a building permit with the local authority, and completely dominating the appointed architect Willard Sears. Once the building was completed, Isabella spent a year on the interior design, arranging the collection precisely in her preferred non-traditional ways. Typically, this involved the creation of eclectic ensembles of furniture, textiles and objects from different cultures and periods among well-known European paintings and sculpture [17].

Isabella’s main focus was on European art. Her approach, perhaps reflecting her personality, was bold and ambitious, targeting and obtaining major works by artists such as Botticelli, Rembrandt Titian, Fra Angelico, Velazquez and, as we have seen, Vermeer. The Gardners’ house, extensive as it was, soon became too crowded for the burgeoning collection and the couple turned their minds to creating their own purpose-built museum. Following Jack’s death in 1898, Isabella moved swiftly to put this into practice, purchasing land and having plans made for a new building, Fenway Court. It was modelled ambitiously on Venetian Renaissance palaces [15], based round a central courtyard (Fig 7); however, rumours that the building was being transported stone by stone from Venice were, sadly, unfounded.

Establishment of the Gardner Museum

Isabella took a deep and almost obsessive interest in the design, construction and decoration of the museum, insisting that her exact wishes, and no-one else’s, must be followed, even in the smallest of details [16]. She forged ahead with the project, ignoring dissenting views, never even bothering to lodge development plans, or to get a building permit with the local authority, and completely dominating the appointed architect Willard Sears. Once the building was completed, Isabella spent a year on the interior design, arranging the collection precisely in her preferred non-traditional ways. Typically, this involved the creation of eclectic ensembles of furniture, textiles and objects from different cultures and periods among well-known European paintings and sculpture [17].

The museum finally opened in 1903, creating a sensation, with the celebration being hailed as “the party of the decade and even of the century”. The eminent William James described the scene as “unbelievably beautiful… The thrill of it was beyond words” [18]. It was undoubtedly a triumph, a complete vindication of Isabella’s personal vision, energy, taste and skill. The Museum would also prove to be the prototype for a number of other private art museums, such as the Frick Museum in New York, the Walters in Baltimore and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles [19].

On Isabella’s death in 1924, aged 84, her will required that her collection be permanently exhibited "for the education and enjoyment of the public forever", according to her aesthetic vision and intent. By that stage it comprised over 7,500 paintings, sculptures, furniture, textiles, silver and ceramics, 1,500 rare books, 7,000 archival objects, and 7,000 letters

.

Thieves in the night

76 years later, as we have foreshadowed, that vast number of artworks would be reduced by thirteen, with the audacious and notorious “theft of the century” that included The Concert.

On Isabella’s death in 1924, aged 84, her will required that her collection be permanently exhibited "for the education and enjoyment of the public forever", according to her aesthetic vision and intent. By that stage it comprised over 7,500 paintings, sculptures, furniture, textiles, silver and ceramics, 1,500 rare books, 7,000 archival objects, and 7,000 letters

.

Thieves in the night

76 years later, as we have foreshadowed, that vast number of artworks would be reduced by thirteen, with the audacious and notorious “theft of the century” that included The Concert.

|

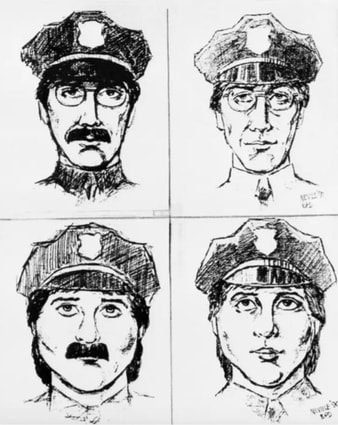

The theft was planned, rather than spontaneous. It started in the middle of the guards’ night shift when the two thieves, in police uniforms and wearing false moustaches, demanded entry to the Museum side door on the pretext that they had heard of “a disturbance in the courtyard”.

Once inside, they handcuffed the two unsuspecting & inexperienced security guards, bound them with duct tape and confined them in the Museum’s basement. |

------------------------------------------------------------------------ What was stolen

Jan Vermeer, The Concert 1664 (Fig 1) Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man 1633 (Fig 8) Rembrandt van Rijn, A Lady and Gentleman in Black 1633) Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee 1633 (Fig 9) Govaert Flinck, Landscape with Obelisk 1638 Edouard Manet, Chez Tortoni c 1875 Edgar Degas, 5 Works on Paper 1857-88 Bronze Eagle Finial, 1813-14 Ancient Chinese Gu (beaker) 1200-1100 BC ------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

The thieves first went to the Dutch Room, where they took The Concert, the Rembrandt self-portrait (Fig 8) -- ironically, the first work Isabella had purchased with the Museum specifically in mind [20] -- and four other works. The Manet, five drawings by Degas, and the two other Rembrandts, including Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee (Fig 9), were taken from other rooms. A number of the works were treated rather clumsily, with some simply being torn from their frames. Curiously, some of the works that were taken were of modest value – such as a Napoleonic banner, which the thieves abandoned after unsuccessfully trying to remove it from the wall -- while other far more valuable works, such as Titian’s The Rape of Europa, were left untouched.

Loaded with their booty, the thieves loaded it into their car – it took two trips to load -- never to be seen again, leaving broken glass and shreds of canvas littering the Museum floor. The entire operation had lasted just 81 minutes, and the crime was not discovered until the next morning when the next shift of security guards arrived.

Just who was responsible, either for actually carrying out the theft, organising it or dealing with the proceeds, has never been conclusively resolved. Despite an exhaustive investigation, numerous prominent leads, deep suspicions, massive reward offers and a virtual blitz of books and articles putting forward theories and speculations – even including a 2021 Netflix series -- it remains the largest unsolved property crime in US history [21].

To this day, the empty frames of the stolen works hang mute on the walls, awaiting – rather forlornly – their hoped-for eventual return. As those artworks have now been missing for over 30 years, away from the normal conservation processes and conditions that apply in a museum setting, it may well be that their physical condition has substantially deteriorated, assuming they are still in existence at all.

To this day, the empty frames of the stolen works hang mute on the walls, awaiting – rather forlornly – their hoped-for eventual return. As those artworks have now been missing for over 30 years, away from the normal conservation processes and conditions that apply in a museum setting, it may well be that their physical condition has substantially deteriorated, assuming they are still in existence at all.

Conclusion

It is now almost 100 years since Isabella died, never to know of the heartbreaking theft of her precious paintings.

In her will she asked the Cowley Brothers religious order, with whom she had a deep and long-standing relationship, to hold a memorial service for her on or round her birthday, 14 April. In recent years, this service has taken the form of a rather scaled-down Requiem Mass for the Repose of her Soul, held in the chapel of her museum.

Isabella was definitely no saint, but as one reporter attending the service observed, “Yesterday, with pure April sunshine streaming through the vaulted skylights, and a superb choir belting out a Gregorian Missa pro defunctis, it was quite easy to believe that somewhere out there, a soul was at peace” [22] ■

© Philip McCouat, 2022. First published April 2022

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Vermeer’s Concert, the Gardner collection, and the art heist of the century”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. For another article on Vermeer, see The Sphinx of Delft

Return to HOME

End notes

[1] For an invaluable source of information on all aspects of Vermeer’s life and works, see http://www.essentialvermeer.com/catalogue/concert.html

[2] For speculation on the identity of the models used by Vermeer for this painting, see B Binstock, “Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism”, Palgrave Commun 3, 17068 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.68

[3] For more on the use of the viola da gamba, see our article on the Isenheim Altarpiece

[4] Hans Koningsberger, The World of Vermeer, Time-Life Library of Art, Netherlands, 1979, at 65, 75-6

[5] Koningsberger, op cit, note [3] at 157

[6] JM Montias, Vermeer and his Milieu: A Web of Social History, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1989, at 122

[7] The relationship between Vermeer’s works and cinematography is discussed in Ann Hollander, Moving Pictures, Harvard University Press, London 1991, for example at 140-143

[8] Edwin Buijsen, "Music in the Age of Vermeer," in Donld Haks et al, Dutch Society in the Age of Vermeer, Wanderers Publishers, 1996, at 110; Amsterdam itself was also a centre for music publishing: Marjorie E. Weisman, Vermeer and Music: The Art of Love and Leisure National Gallery, London, 2013 at 22–24.

[9] B Binstock, op cit, note [1]

[10] Elizabeth Capel, “Money alone was not enough: Continued Gendering of Women’s Gilded Age and Progressive Era Art Collecting Narratives”. International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities, 6(1), p.1, 2014. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7710/2168-0620.1013

[11] For the details of her life and works, see generally Douglass Shand-Tucci, The Art of Scandal, HarperPerennial, New York, 1997

[12] Shand-Tucci, op cit, note [10] at 168-9. Some accounts say $5,000

[13] Alan Chong, "The Concert," in Eye of the Beholder, ed Alan Chong et al, ISGM and Beacon Press, Boston, 2003, at 149

[14] Capel. op cit, note [9]

[15] Shand-Tucci, op cit, note [10] at197ff, 220ff

[16] Shand-Tucci, op cit [10] at 207

[17] For more on the design see Shand-Tucci, op cit, note [10] at 220ff. For details of the rooms of the Museum, see https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience/rooms

[18] Shand-Tucci, op cit [10] at 213

[19] Shand-Tucci, op cit [10] at 219

[20] Shand-Tucci, op cit [10] at 196

[21] For a useful, non-exhaustive list of publications on the theft, see https://www.futilitycloset.com/2018/05/21/podcast-episode-201-the-gardner-heist/

[22] Alex Beam “Mrs Gardner’s annual claim on heaven”, The Boston Globe, 19 April 1995 http://mcnsarticles.blogspot.com/2003_11_09_archive.html

© Philip McCouat, 2022

Return to HOME

It is now almost 100 years since Isabella died, never to know of the heartbreaking theft of her precious paintings.

In her will she asked the Cowley Brothers religious order, with whom she had a deep and long-standing relationship, to hold a memorial service for her on or round her birthday, 14 April. In recent years, this service has taken the form of a rather scaled-down Requiem Mass for the Repose of her Soul, held in the chapel of her museum.

Isabella was definitely no saint, but as one reporter attending the service observed, “Yesterday, with pure April sunshine streaming through the vaulted skylights, and a superb choir belting out a Gregorian Missa pro defunctis, it was quite easy to believe that somewhere out there, a soul was at peace” [22] ■

© Philip McCouat, 2022. First published April 2022

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Vermeer’s Concert, the Gardner collection, and the art heist of the century”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. For another article on Vermeer, see The Sphinx of Delft

Return to HOME

End notes

[1] For an invaluable source of information on all aspects of Vermeer’s life and works, see http://www.essentialvermeer.com/catalogue/concert.html

[2] For speculation on the identity of the models used by Vermeer for this painting, see B Binstock, “Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism”, Palgrave Commun 3, 17068 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.68

[3] For more on the use of the viola da gamba, see our article on the Isenheim Altarpiece

[4] Hans Koningsberger, The World of Vermeer, Time-Life Library of Art, Netherlands, 1979, at 65, 75-6

[5] Koningsberger, op cit, note [3] at 157

[6] JM Montias, Vermeer and his Milieu: A Web of Social History, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1989, at 122

[7] The relationship between Vermeer’s works and cinematography is discussed in Ann Hollander, Moving Pictures, Harvard University Press, London 1991, for example at 140-143

[8] Edwin Buijsen, "Music in the Age of Vermeer," in Donld Haks et al, Dutch Society in the Age of Vermeer, Wanderers Publishers, 1996, at 110; Amsterdam itself was also a centre for music publishing: Marjorie E. Weisman, Vermeer and Music: The Art of Love and Leisure National Gallery, London, 2013 at 22–24.

[9] B Binstock, op cit, note [1]

[10] Elizabeth Capel, “Money alone was not enough: Continued Gendering of Women’s Gilded Age and Progressive Era Art Collecting Narratives”. International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities, 6(1), p.1, 2014. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7710/2168-0620.1013

[11] For the details of her life and works, see generally Douglass Shand-Tucci, The Art of Scandal, HarperPerennial, New York, 1997

[12] Shand-Tucci, op cit, note [10] at 168-9. Some accounts say $5,000

[13] Alan Chong, "The Concert," in Eye of the Beholder, ed Alan Chong et al, ISGM and Beacon Press, Boston, 2003, at 149

[14] Capel. op cit, note [9]

[15] Shand-Tucci, op cit, note [10] at197ff, 220ff

[16] Shand-Tucci, op cit [10] at 207

[17] For more on the design see Shand-Tucci, op cit, note [10] at 220ff. For details of the rooms of the Museum, see https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience/rooms

[18] Shand-Tucci, op cit [10] at 213

[19] Shand-Tucci, op cit [10] at 219

[20] Shand-Tucci, op cit [10] at 196

[21] For a useful, non-exhaustive list of publications on the theft, see https://www.futilitycloset.com/2018/05/21/podcast-episode-201-the-gardner-heist/

[22] Alex Beam “Mrs Gardner’s annual claim on heaven”, The Boston Globe, 19 April 1995 http://mcnsarticles.blogspot.com/2003_11_09_archive.html

© Philip McCouat, 2022

Return to HOME