FORGOTTEN WOMEN ARTISTS

#4 Michaelina Wautier: entering the limelight after 300 years

By Philip McCouat For comments on this article see here

This is the fourth in our series of articles discussing the lives and works of distinguished women artists from the past who have largely been forgotten. Other articles in the series have dealt with Arcangela Paladini, Jane Loudon, Marie-Gabrielle Capet and Thérèse Schwartze

This is the fourth in our series of articles discussing the lives and works of distinguished women artists from the past who have largely been forgotten. Other articles in the series have dealt with Arcangela Paladini, Jane Loudon, Marie-Gabrielle Capet and Thérèse Schwartze

A chance sighting

Back in 1993 a young art historian, Katlijne Van der Stighelen, was attending a symposium at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. As a specialist in Flemish art, she was interested in viewing a portrait attributed to Van Dyck that was in storage. As Stighelen tells it, “a curator led me down long corridors in which ‘second class’ Flemish paintings were stored. As I was leaving the stores, my eye fell upon a monumental piece I hadn’t seen before” [1]. Here is what she saw:

It was certainly not a Van Dyck. It was an enormous Bacchanal, almost 9 feet high and 12 ft wide, and it was executed in a style which was not familiar to Van der Stighelen’s experienced eye. The curator told her that it was painted in 1659 by an obscure artist named Michaelina Wautier. From that moment, Stighelen realised that this was an outstanding talent which needed to be fully explored.

In this article, we look at what Van der Stighelen was able to uncover, and how a virtually unknown painter finally entered the limelight of art history.

In this article, we look at what Van der Stighelen was able to uncover, and how a virtually unknown painter finally entered the limelight of art history.

a TALENT THAT EMERGES FULLY-FORMED

We still know very little of Michaelina Wautier’s personal life [2]. She was born into a large, fairly well-off family in 1604 and grew up in Mons, in present-day Belgium. After she eventually left home, when both parents had died, she joined her brother Charles, also a painter. They lived in, and possibly also shared a studio, in a large house in Brussels, near the Gothic church Notre Dame de la Chapelle.

Both Michaelina and Charles evidently were active in business, particularly in real estate. Both also were almost certainly well-trained in art, but we don’t know where or with whom. Michaelina, like Charles, would never marry.

In this self-portrait, she shows how she would like to be seen -- as professional, serious and elegant.

Both Michaelina and Charles evidently were active in business, particularly in real estate. Both also were almost certainly well-trained in art, but we don’t know where or with whom. Michaelina, like Charles, would never marry.

In this self-portrait, she shows how she would like to be seen -- as professional, serious and elegant.

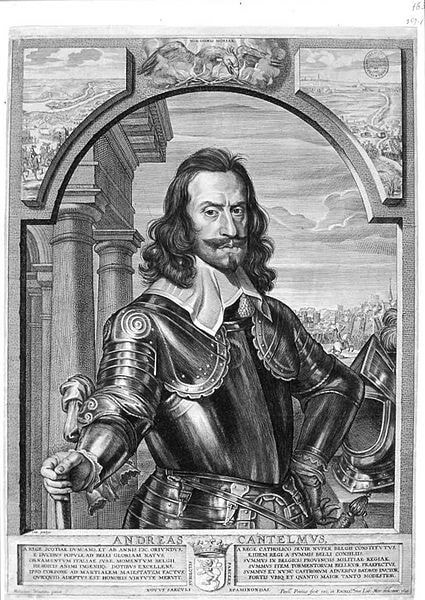

Michaelina does not appear to have taken up art seriously until her late 30s, but her talent evidently did not long go unnoticed. Possibly as a result of Charles’ contacts in the army – he had previously been an officer – she was commissioned to do a portrait of the aristocratic general Andrea Cantelmo. That painting has since disappeared, but we know it through an engraving of it done by Paulus Pontius (Fig 3) [3].

This portrait, together with her evidently growing reputation, and other contacts made through her ennobled elder brothers, may well have been factors in creating some interest at the Brussels Court of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, a noted art patron [4]. In any event, we know that Leopold Wilhelm commissioned or purchased four works by Michaelina, including the Bacchanal [5]; they are listed in a 1659 inventory of his collection -- incidentally, one of the few documentary references to her works [6]. We can therefore assume that her career was established by then, and that it would be likely to flourish as her artistic output increased.

A refusal to be limited

As discussed in our introductory article on forgotten women artists, female artists have traditionally faced a number of hurdles in establishing themselves, so there would not have been many Belgian role models for Michaelina. Certainly, Clara Peeters had established a thriving business in still lifes, and Judith Leyster was also prominent, but there is no evidence that Michaelina was influenced by either of these forthright artists. In fact, the impression one gets is that she was extremely self-possessed and confident in her own ability, and seemed to did not feel too many constraints in what she chose to paint. Indeed, one of the most remarkable aspects of Michaelina’s output, currently estimated to number about 30 works, is that it covered so many genres -- not just portraits, as was originally thought – but also large scale “history” paintings [7], still lifes and scenes of daily life. What’s more, with few exceptions, she seemed to be able to switch to new genres with striking maturity, seemingly able to avoid the pitfalls that often accompany radical changes in subject matter.

This virtuosity is perhaps best displayed in her mythological work, the Bacchanal (see Fig 1). It includes a dozen figures, mostly partially nude males, and Wautier displays dexterity and skill in depicting the human figure, even though women were officially barred from studying live models. The scale of this painting was also most surprising -- normally, women were patronisingly regarded as not being capable of such large-scale complex works. And to top it off she includes herself, looking directly at the viewer, with one breast exposed. It is indeed an astonishing convention-breaking achievement for its time.

Decline of reputation after death

Strangely, the recognition and reputation that Michaelina steadily built up in the 1640s and 50s seems to have evaporated quite quickly after she died [8]. There appears to be a number of reasons for this. First, there was a long period between her last painting (believed to be in 1659) and her death in 1689, at the advanced age of 85, during which she was not producing paintings or staying in the public eye. Second, unlike some of her female contemporaries, including the Italians Artemisia Gentileschi and Elizabetta Sirani, her self-portrait (Fig 2) was never issued as a print to perpetuate her memory [9]. In fact, eventually that self-portrait itself was later attributed to Gentileschi [10].

The third reason was that in her Will, Michaelina left all her possessions to Charles, and most of her paintings probably remained with her family. Those that eventually found their way onto the market were no longer recognised, as her name had been forgotten in the meantime. Additionally, most of her paintings, like the self-portrait, became attributed to others, or appropriated by them or their supporters. Over time her name also disappeared from the numerous versions that were issued of the engraving of her Cantelmo portrait.

Finally, difficulties of identification arose from confusion over her own name (she was christened as Maria Magdalena and the spelling of her surname was extremely variable). She was also confused with Charles, to whom a number of her paintings were misattributed [11], and with whom she may have collaborated on some works. Further confusion occurred with a mysterious “N Woutiers”; and with Rubens’ pupil Frans Wouters, to whom two of the Saints pictures were misattributed. And so it went, a process familiar for many female artists, the gradual loss of an identity and a reputation.

The third reason was that in her Will, Michaelina left all her possessions to Charles, and most of her paintings probably remained with her family. Those that eventually found their way onto the market were no longer recognised, as her name had been forgotten in the meantime. Additionally, most of her paintings, like the self-portrait, became attributed to others, or appropriated by them or their supporters. Over time her name also disappeared from the numerous versions that were issued of the engraving of her Cantelmo portrait.

Finally, difficulties of identification arose from confusion over her own name (she was christened as Maria Magdalena and the spelling of her surname was extremely variable). She was also confused with Charles, to whom a number of her paintings were misattributed [11], and with whom she may have collaborated on some works. Further confusion occurred with a mysterious “N Woutiers”; and with Rubens’ pupil Frans Wouters, to whom two of the Saints pictures were misattributed. And so it went, a process familiar for many female artists, the gradual loss of an identity and a reputation.

A belated revival of interest

Almost two centuries later, however, some glimmers of recognition started to reappear [12]. From the 1850s onwards, she began to be mentioned in her own right, typically as a portraitist “of some talent”, though with very few known works. In addition, the misattribution of her two Saints pictures began to be recognised and corrected.

This low-scale level of interest continued into the 20th century. In 1960, a previously unrecognised floral still life, Garland with a Butterfly, mysteriously turned up in an exhibition, and just as mysteriously disappeared in 1985 [13]. In 1967, she was finally identified as the artist of the Bacchanal. In 1979, in her ground-breaking work on women painters, Germaine Greer noted “the fluent brushwork, relaxed posture and confident use of chiaroscuro” in Michaelina’s Portrait of in a Commander the Spanish Army (Fig 6), concluding that it was painted with a “swiftness and accuracy” which suggested regular professional practice. Prophetically, Greer suggested that there should be other works by Michaelina to be found, given that she was such an experienced professional, and that so few works of hers were known (Greer knew of only four) [14].

This low-scale level of interest continued into the 20th century. In 1960, a previously unrecognised floral still life, Garland with a Butterfly, mysteriously turned up in an exhibition, and just as mysteriously disappeared in 1985 [13]. In 1967, she was finally identified as the artist of the Bacchanal. In 1979, in her ground-breaking work on women painters, Germaine Greer noted “the fluent brushwork, relaxed posture and confident use of chiaroscuro” in Michaelina’s Portrait of in a Commander the Spanish Army (Fig 6), concluding that it was painted with a “swiftness and accuracy” which suggested regular professional practice. Prophetically, Greer suggested that there should be other works by Michaelina to be found, given that she was such an experienced professional, and that so few works of hers were known (Greer knew of only four) [14].

During the 1990s, further important reattributions were made, and some of her works started appearing in exhibitions. In 1993, as we have seen, Katlijne Van der Stighelen caught her first sight of the Bacchanal. Samuel Herzog later described this painting as the “unofficial highlight” of a small-scale exhibition at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, remarking that it showed “the courage and humour” of the artist [15]. Further evidence of the growing interest can be gauged by the result of a Zurich auction of Michaelina’s Portrait of the Jesuit Missionary Martino Martini in 2016 (Fig 7). Its reserve price was $US7,000 – 10,000; it sold for $400,000, some 40 times the upper reserve. Similarly, her small still life Garland of Flowers with Dragonfly, sold for $US 471,000 in January 2019 [15A].

A reputation restored

Recognition of Michaelina’s talent finally reached a high point with the first major retrospective of her works held in 2018, as a joint partnership between the Rubens House and the Antwerp Museum (MAS). The exhibition, inspired and curated by Van der Stighelen, brought together over 20 of Michaelina’s known works and enabled a full appreciation to be made of her versatility.

Suddenly, Michaelina seemed to be everywhere. As the exhibition proceeded, Van der Stighelen noted, “[R]ight now there is an enormous jigsaw puzzle in Antwerp Central Station, which allows every passer-by a chance to put the pieces of Wautier’s most important work, the Triumph of Bacchus [Fig 1], back together. Bus shelters are covered in a reproduction of Two Bubble-Blowing Boys, a scene of children blowing bubbles and enjoying themselves, reminding the viewer that life is as fleeting as soap bubbles. Portrait of Two Girls as the Saints Agnes and Dorothy (Fig 4) has already become a firm favourite with the public. Heading towards the Museum aan de Stroom, you can see banners with Wautier’s self-portrait [Fig 2] fluttering on the esplanade. Every major newspaper and art magazine in Belgium has published articles about the exhibition” [16].

Suddenly, Michaelina seemed to be everywhere. As the exhibition proceeded, Van der Stighelen noted, “[R]ight now there is an enormous jigsaw puzzle in Antwerp Central Station, which allows every passer-by a chance to put the pieces of Wautier’s most important work, the Triumph of Bacchus [Fig 1], back together. Bus shelters are covered in a reproduction of Two Bubble-Blowing Boys, a scene of children blowing bubbles and enjoying themselves, reminding the viewer that life is as fleeting as soap bubbles. Portrait of Two Girls as the Saints Agnes and Dorothy (Fig 4) has already become a firm favourite with the public. Heading towards the Museum aan de Stroom, you can see banners with Wautier’s self-portrait [Fig 2] fluttering on the esplanade. Every major newspaper and art magazine in Belgium has published articles about the exhibition” [16].

And the hunt for her lost works is on

Not surprisingly, the discovery of such a new talent has prompted a hunt for works by Michaelina which may have been misattributed in the past, or which have lain unappreciated in private ownership or gallery store-rooms. In June 2018, for example, it was announced that the painting Everyone his Fancy (Fig 8), formerly attributed to Jacob Van Oost, has now been reattributed to Michaelina [17].

Similarly, in 2021, it was announced that a complete cycle of Michaelina’s paintings representing the five senses – previously considered to be lost -- has been relocated; they are now making their first appearance in 370 years at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Fig 9) [18]. In 2023, a previously-unknown Study of a Head of a Bearded Man (c1655) was authenticated [19]..Efforts are also being made to locate other works such as an image of a flute player, which appeared an auction catalogue in 1975, but then disappeared; and the previously mentioned still-life Garland with Butterfly which disappeared in 1985.

Of course, this is an area in which considerable caution will be needed. Attributions affected by overenthusiasm or even chicanery are an ever-present challenge where so little is still known of Michaelina’s life and work.

Conclusion

Michaelina Wautier is unusual in many ways. A woman painter, prominent in the 17th century, with an extraordinarily wide range, her own individual style, a familiarity with the male body, and an ability to deal with highly complex compositions. Indeed, she seemed to be able to overcome so many obstacles that traditionally stood in the way of women seeking to establish a career in art, that it comes as a surprise that, through no fault of her own, she was unable to surmount the final hurdle ~ ensuring that her name lived on, and that her work was not dissipated or misattributed. That such recognition was realised at all, even though belatedly, can largely be attributed to Van der Stighelen. As the director of the Rubens House has pointed out, “without her years-long academic quest, Michaelina would still be a footnote in art history at best” [20] ■

© Philip McCouat 2019. First published April 2019, updated December 2021, June 2023.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Forgotten Women Artists#4: Michaelina Wautier: entering the limelight after 300 years”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. For other articles in this series, see:

Forgotten Women Artists #2: Jane Loudon: Artist, Futurist, Horticulturist and Author

Forgotten Women Artists #1: Arcangela Paladini: The Rapid Rise and Fall of a Prodigy

Forgotten Women Artists #3: Marie-Gabrielle Capet: Stepping Out from the Shadows

Forgotten Women Artists #5: Thérèse Schwartze and the business of painting

Return to HOME

© Philip McCouat 2019. First published April 2019, updated December 2021, June 2023.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Forgotten Women Artists#4: Michaelina Wautier: entering the limelight after 300 years”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. For other articles in this series, see:

Forgotten Women Artists #2: Jane Loudon: Artist, Futurist, Horticulturist and Author

Forgotten Women Artists #1: Arcangela Paladini: The Rapid Rise and Fall of a Prodigy

Forgotten Women Artists #3: Marie-Gabrielle Capet: Stepping Out from the Shadows

Forgotten Women Artists #5: Thérèse Schwartze and the business of painting

Return to HOME

end notes

[1] Katlijne Van der Stighelen, “Doing justice to an artist no-one knows is quite an undertaking”, Apollo Magazine, 2 July 2018 https://www.apollo-magazine.com/doing-justice-to-an-artist-no-one-knows-is-quite-an-undertaking/

[2] Katlijne Van der Stighelen, Michaelina Wautier 1604-1689 Glorifying a Forgotten Talent, BAI, Kontich, 2018. This invaluable book, the principal source of information on the artist, accompanied the 2018 retrospective exhibition in Antwerp, ‘Michaelina Wautier, Baroque’s Leading Lady’, which was curated by Van der Stighelen. I have drawn heavily on it in the preparation of this article.

[3] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 25.

[4] Michaelina’ brother Charles actually painted a portrait of Leopold Wilhelm in 1655: Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 27.

[5] The other three were two portraits of St Joachim and one of St Joseph: Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 53, 63.

[6] There is also an entry in the accounts book of Adam-Pierre de la Grenée, official dance-master to the Brussels Court, recording his purchase of a work from “Madamoiselle Woutier”, in January 1650: Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 296-7.

[7] Such as The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine.

[8] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 36.

[9] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 46.

[10] By Walter Shaw Sparrow in his monumental Women Painters of the World, 1905.

[11] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 41ff.

[12] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 43.

[13] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 45.

[14] Germaine Greer, The Obstacle Race: The fortunes of women painters and their work, Picador, London, 1981; Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 254, 352.

[15] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 46.

[15A] However, a partly-finished and less impressive “Portrait Historie” (c 1650), attributed to Michaelina Wautier, failed to sell at auction in December 2018: Blount Artinfo, 25 December 2018 https://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/3450158/a-long-lost-michaelina-wautier-painting-failed-to-get-a-buyer

[16] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 1.

[17] The Art Newspaper, 20 June 2018, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/new-discovery-by-baroque-s-forgotten-female-master-michaelina-wautier-added-to-recently-opened-first-exhibition

[18] "MFA Boston to Open Suite of Seven Renovated Galleries Dedicated to New Displays and Interpretation of Dutch and Flemish Art", 18 November 2021, https://www.mfa.org/press-release/dutch-and-flemish-art; Katrijn Van Bragt, “Six Paintings by 17th century artist Michaelina Wautier sought by Rubens House”, 26 April 2017 https://www.codart.nl/art-works/six-paintings-17th-century-artist-michaelina-wautier-sought-rubens-house/

[19] "M.Leuven Acquires Rare Masterpiece by Michaelina Wautier" https://www.artdependence.com/articles/m-leuven-acquires-rare-masterpiece-by-michaelina-wautier/

[20] Ben Van Beneden, “Acknowledgements” in Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2.

© Philip McCouat 2019. First published April 2019, updated December 2021, June 2023,..

Return to HOME

[2] Katlijne Van der Stighelen, Michaelina Wautier 1604-1689 Glorifying a Forgotten Talent, BAI, Kontich, 2018. This invaluable book, the principal source of information on the artist, accompanied the 2018 retrospective exhibition in Antwerp, ‘Michaelina Wautier, Baroque’s Leading Lady’, which was curated by Van der Stighelen. I have drawn heavily on it in the preparation of this article.

[3] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 25.

[4] Michaelina’ brother Charles actually painted a portrait of Leopold Wilhelm in 1655: Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 27.

[5] The other three were two portraits of St Joachim and one of St Joseph: Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 53, 63.

[6] There is also an entry in the accounts book of Adam-Pierre de la Grenée, official dance-master to the Brussels Court, recording his purchase of a work from “Madamoiselle Woutier”, in January 1650: Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 296-7.

[7] Such as The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine.

[8] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 36.

[9] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 46.

[10] By Walter Shaw Sparrow in his monumental Women Painters of the World, 1905.

[11] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 41ff.

[12] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 43.

[13] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 45.

[14] Germaine Greer, The Obstacle Race: The fortunes of women painters and their work, Picador, London, 1981; Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 254, 352.

[15] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2, at 46.

[15A] However, a partly-finished and less impressive “Portrait Historie” (c 1650), attributed to Michaelina Wautier, failed to sell at auction in December 2018: Blount Artinfo, 25 December 2018 https://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/3450158/a-long-lost-michaelina-wautier-painting-failed-to-get-a-buyer

[16] Van der Stighelen, op cit note 1.

[17] The Art Newspaper, 20 June 2018, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/new-discovery-by-baroque-s-forgotten-female-master-michaelina-wautier-added-to-recently-opened-first-exhibition

[18] "MFA Boston to Open Suite of Seven Renovated Galleries Dedicated to New Displays and Interpretation of Dutch and Flemish Art", 18 November 2021, https://www.mfa.org/press-release/dutch-and-flemish-art; Katrijn Van Bragt, “Six Paintings by 17th century artist Michaelina Wautier sought by Rubens House”, 26 April 2017 https://www.codart.nl/art-works/six-paintings-17th-century-artist-michaelina-wautier-sought-rubens-house/

[19] "M.Leuven Acquires Rare Masterpiece by Michaelina Wautier" https://www.artdependence.com/articles/m-leuven-acquires-rare-masterpiece-by-michaelina-wautier/

[20] Ben Van Beneden, “Acknowledgements” in Van der Stighelen, op cit note 2.

© Philip McCouat 2019. First published April 2019, updated December 2021, June 2023,..

Return to HOME