Understanding Petrus Christus’

A Goldsmith in his Shop

By Philip McCouat For readers' comments on this article, see here

What we can see

Petrus Christus’ A Goldsmith in his Shop (1449) depicts a red-clad goldsmith at his counter, weighing a golden ring on his scales. Just behind him, an expensively-dressed man and woman are watching him at work, the man with a proprietorial arm around the woman’s shoulders, the woman stretching out her hand for something. The man and woman are evidently a couple, and their sumptuous and fashionable clothing mark them either as members of the court of the Duke of Burgundy (Philip the Good) or the few wealthy burghers who were able to mix with the aristocracy [1]. A red wedding girdle lying on the counter confirms that are betrothed, and the ring in the goldsmith’s scales is likely to be a wedding ring that they are inspecting, the man rather appraisingly, the woman possibly more eagerly. Oddly, however, the goldsmith’s attention is not focused on the scales, nor on the couple, but of something off to the side, towards the source of light, out of our sight.

This painting is a fine example of how much an artwork can tell us, if only we know where to look, and are able to appreciate the significance of its many small details. In this article -- even though we may just be scratching the surface -- we’ll attempt to do just that.

This painting is a fine example of how much an artwork can tell us, if only we know where to look, and are able to appreciate the significance of its many small details. In this article -- even though we may just be scratching the surface -- we’ll attempt to do just that.

The goldsmith’s tools of trade

We see the goldsmith sitting surrounded by a wide range of the implements of his trade [2]. Their sheer variety attest to the role important of goldsmiths in the service of both religious and secular segments of the community [3].

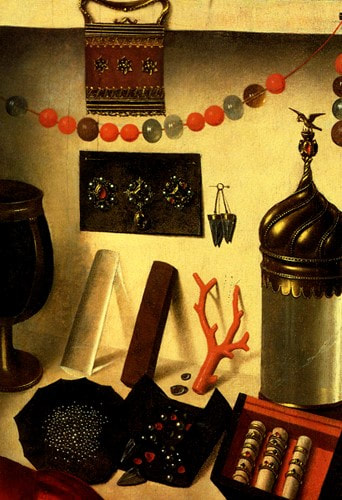

On the top shelf (Fig 1), there are a number of pewter donation pitchers, which the city’s aldermen might offer to distinguished guests on official occasions [4]. On the edge of the shelf (Fig 2) a fancy buckle hangs above a string with amber beads. On the lower level, we can see a tray full of rings, a wallet of loose gems, a panel with samples of brooches, a coconut-shell goblet, a piece of red coral, and two small stone plinths leaning against the back wall. On the far right stands a gold and glass vessel, with a pelican at its apex pricking its breast to feed its young, a traditional depiction of self-sacrifice, reflecting the fate of Christ; it was possibly used for relics or consecrated wafers [5]. Hanging from a nail are two fossilised shark teeth; these were believed to detect poison by changing colour on contact (these were sometimes referred to as “serpents’ tongues”).

On the top shelf (Fig 1), there are a number of pewter donation pitchers, which the city’s aldermen might offer to distinguished guests on official occasions [4]. On the edge of the shelf (Fig 2) a fancy buckle hangs above a string with amber beads. On the lower level, we can see a tray full of rings, a wallet of loose gems, a panel with samples of brooches, a coconut-shell goblet, a piece of red coral, and two small stone plinths leaning against the back wall. On the far right stands a gold and glass vessel, with a pelican at its apex pricking its breast to feed its young, a traditional depiction of self-sacrifice, reflecting the fate of Christ; it was possibly used for relics or consecrated wafers [5]. Hanging from a nail are two fossilised shark teeth; these were believed to detect poison by changing colour on contact (these were sometimes referred to as “serpents’ tongues”).

Many of these gems and other items on display were also believed to have powerful protective qualities; the ruby, for example, “resists poyson, resists sadness, restrains lust, drives away frightful dreams, clears the mind, keeps the body safe and, if a mischance be at hand, it signifies this by turning of a darker colour” [6]. Sapphires were said to heal ulcers, eye diseases, and amber to protect from diseases of the throat. Branched coral could be used to fend off the evil eye or stop bleeding, and coconut shell could counter poisoning [7].

In the foreground, on the bench, the goldsmith is weighing a ring with a pair of scales, with the weights being taken from a round-lidded receptacle. There is a scattering of gold coins, possibly reflecting the inclusion of money changers in the goldsmiths’ guild. The traditional wedding girdle, no doubt associated with the couple, lies gracefully curled on the bench. On the viewer’s right, a cleverly-placed convex mirror reflects the street outside with the characteristically red-brick facades of Bruges houses, and a gentleman and his falconer standing looking into the shop. As the falcon was sometimes suggestive of pride (as was a mirror), it’s possible that Christus was reminding us here of the imperfections of the outside world, in contrast to the supposedly admirable virtue of the betrothed couple [8].

In the foreground, on the bench, the goldsmith is weighing a ring with a pair of scales, with the weights being taken from a round-lidded receptacle. There is a scattering of gold coins, possibly reflecting the inclusion of money changers in the goldsmiths’ guild. The traditional wedding girdle, no doubt associated with the couple, lies gracefully curled on the bench. On the viewer’s right, a cleverly-placed convex mirror reflects the street outside with the characteristically red-brick facades of Bruges houses, and a gentleman and his falconer standing looking into the shop. As the falcon was sometimes suggestive of pride (as was a mirror), it’s possible that Christus was reminding us here of the imperfections of the outside world, in contrast to the supposedly admirable virtue of the betrothed couple [8].

Christus’s use the mirror to create this trick of perspective enables the viewer to simultaneously see what lies before her/ him (the goldsmith) and what lies behind (the falconer and the city). Christus’ highly-influential predecessor, Jan van Eyck, was similarly interested in exploring the depiction of convincing perspective (and of meticulous detail), and used a similar device in his famous Arnolfini Wedding. In that painting, the convex mirror – this time situated behind the betrothed couple -- enables the viewer to see both the front and back of the couple (and the reflection of the otherwise unseen artist).

Saint or artisan, or both?

Traditionally, the goldsmith in this painting was believed to represent St Eligius (or St Eloy), the patron saint of the guild of goldsmiths, blacksmiths and moneychangers. Eligius, born in the 6th century, had been a highly skilled craftsman whose work attracted royal favour patronage, His pious nature led to his appointment as a bishop, and he was credited with attracting many followers, founding several monasteries and churches in the Bruges area, and inspiring a number of miracles [9].

However, it is now generally believed that it is not the saint being portrayed here, but simply a goldsmith. A crucial factor in this reinterpretation was the changed status of a halo which, in the past, had appeared on the goldsmith. This of course had suggested saintliness but, in 1993, after some decades of controversy over its authenticity, the halo was determined to have been added to the original painting, probably in the 19th century, and it was accordingly removed [10].

However, it is now generally believed that it is not the saint being portrayed here, but simply a goldsmith. A crucial factor in this reinterpretation was the changed status of a halo which, in the past, had appeared on the goldsmith. This of course had suggested saintliness but, in 1993, after some decades of controversy over its authenticity, the halo was determined to have been added to the original painting, probably in the 19th century, and it was accordingly removed [10].

Without this halo, there is little evidence left to suggest that the goldsmith is saintly. What’s more, the goldsmith here bears little resemblance to the traditional representations of St Eligius [11], which usually show him as a mitred bishop, dressed in ecclesiastical garb, typically holding a hammer. None of these characteristics appear in this painting. Nor was there any episode in the saint’s life that would account for the presence of the young couple [12]. The fact that Christus used extensive modelling in the underdrawing for the goldsmith’s face – much more than for the couple – also supports the view that the painting is a portrait of an actual person, not an object of devotion.

Tracking down the goldsmith – and the couple

So if the figure is not a saint, but simply a goldsmith, is it of some particular goldsmith?

Commentator Hugo van der Velden has in fact proposed that it is the Bruges goldsmith Willem van Vlueten [13] and, furthermore, that the scene depicted refers to an actual transaction involving a specific couple, not just a generic or ideal aristocratic couple. In 1440. this goldsmith had been commissioned by Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy, to provide a large quantity of gold and silver metalwork as a gift to his niece Mary of Guelders on the occasion of her marriage to James II, King of Scots.

Commentator Hugo van der Velden has in fact proposed that it is the Bruges goldsmith Willem van Vlueten [13] and, furthermore, that the scene depicted refers to an actual transaction involving a specific couple, not just a generic or ideal aristocratic couple. In 1440. this goldsmith had been commissioned by Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy, to provide a large quantity of gold and silver metalwork as a gift to his niece Mary of Guelders on the occasion of her marriage to James II, King of Scots.

Van der Velden suggests that the goldsmith Vlueten later engaged Christus to produce a painting to imaginatively commemorate and advertise this extraordinarily prestigious, important and profitable commission [14]. Such a practice was apparently relatively common at the time among highly successful goldsmiths. In much the same way, the owners of a present-day racehorse that had won a major race might engage an artist to make a painting of the successful race; or a food supplier may advertise that its products are supplied by appointment to the Crown.

This, however, does not mean that the moment depicted in the painting is meant to be a faithful representation of an occasion that actually took place in the workshop -- rather, it simply creates an imaginary scenario to illustrate the fact that Vuelten was the supplier of Philip the Good’s gift of gold and metalwork [15]. The large scale of the painting – it’s a metre high -- with its figures almost life-size, also supports the view that it was intended for such public display, rather than for private devotion.

This, however, does not mean that the moment depicted in the painting is meant to be a faithful representation of an occasion that actually took place in the workshop -- rather, it simply creates an imaginary scenario to illustrate the fact that Vuelten was the supplier of Philip the Good’s gift of gold and metalwork [15]. The large scale of the painting – it’s a metre high -- with its figures almost life-size, also supports the view that it was intended for such public display, rather than for private devotion.

Bruges as an artistic centre

Before we leave this intriguing painting, we should say a word about its geographical context, 15th century Bruges.

It's very fitting that this city should be the setting for a painting that extolled the importance of a goldsmith. Christus had probably settled there in the 1440s, at a time when the city was successfully recovering from a period of social and political turmoil [16]. Bruges was an attractive option because of its financial and commercial prosperity, the possibility of lucrative commissions from the regular presence of the ducal court, and the tastes of luxury-loving local businessmen who were a major source of artistic patronage [17]. Immigrants in fact comprised almost a third of all artists working in Bruges in this era (including van Eyck, Hans Memling and Gerard David) and similar considerations attracted other specialised skilled craftspeople such as furriers, hatters, jewellers and – of course -- goldsmiths.

However, this golden era would not last. Over ensuing decades, Bruges’ international and commercial importance would be eroded by its rapidly-growing rival Antwerp [18]. One factor in this change was the gradual silting up of the Zwin, the connection between Bruges and the North Sea. Another, ironically enough, was Bruges’ over-reliance on the production of luxury goods, rather than more readily tradeable commodities. In time, Antwerp’s more nimble and diversified trade would enable it to take over as the most prominent harbour and centre of commerce and finance in the region.

© Philip McCouat, 2020. First published November 2020.

We welcome your comments on this article.

RETURN TO HOME

It's very fitting that this city should be the setting for a painting that extolled the importance of a goldsmith. Christus had probably settled there in the 1440s, at a time when the city was successfully recovering from a period of social and political turmoil [16]. Bruges was an attractive option because of its financial and commercial prosperity, the possibility of lucrative commissions from the regular presence of the ducal court, and the tastes of luxury-loving local businessmen who were a major source of artistic patronage [17]. Immigrants in fact comprised almost a third of all artists working in Bruges in this era (including van Eyck, Hans Memling and Gerard David) and similar considerations attracted other specialised skilled craftspeople such as furriers, hatters, jewellers and – of course -- goldsmiths.

However, this golden era would not last. Over ensuing decades, Bruges’ international and commercial importance would be eroded by its rapidly-growing rival Antwerp [18]. One factor in this change was the gradual silting up of the Zwin, the connection between Bruges and the North Sea. Another, ironically enough, was Bruges’ over-reliance on the production of luxury goods, rather than more readily tradeable commodities. In time, Antwerp’s more nimble and diversified trade would enable it to take over as the most prominent harbour and centre of commerce and finance in the region.

© Philip McCouat, 2020. First published November 2020.

We welcome your comments on this article.

RETURN TO HOME

End Notes

[1] Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, What Great Paintings Say, Volume 1, Taschen, Cologne, 2003, at 47.

[2] Christopher J Duffin, “Geological Prophylactics in Petrus Christus' Painting A Goldsmith in his shop possibly Saint Eligius (1449) at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268687003; Hagen, op cit, at 48.

[3] Maryan W Ainsworth, with Maximiliaan Martens, Petrus Christus, Renaissance Master of Bruges, Exhibition Catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1994, 96 ff, at 98.

[4] Ainsworth, Petrus Christus, op cit, at 98.

[5] Ainsworth, Petrus Christus, op cit, at 98.

[6] Duffin, op cit.

[7] Hagen, op cit at 46; Duffin, op cit.

[8] Ainsworth, Petrus Christus, op cit, at 98.

[9] Hagen, op cit, at 46.

[10] Hugo van der Velden, “Defrocking St Eloy: Petrus Christus’s Vocational Portrait of a Goldsmith”, Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, Vol. 26, No. 4 (1998), pp. 242-276; Maryan W Ainsworth, “Intentional Alterations of Early Netherlandish Painting”, Essay in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, January 2008.

[11] Velden, op cit at 244.

[12] Velden, op cit at 246.

[13] Velden, op cit at 242.

[14] Velden, op cit at 257-261. See, for example, van Eyck’s portrait of prominent Bruges goldsmith Jan de Leeuwn (1436).

[15] Velden, op cit at 262.

[16] Maximiliaan Martens, in Ainsworth, Petrus Christus, op cit at 15

[17] Martens, op cit at 4ff. Christus would also have been attracted by the fact that the fee required to obtain citizenship (and therefore membership of the painters’ guild) had recently been reduced.

[18] Martens, op cit. On the growth of Antwerp, see our article Lost in Translation http://www.artinsociety.com/lost-in-translation-bruegelrsquos-tower-of-babel-new-page.html

© Philip McCouat, 2020.

RETURN TO HOME

[2] Christopher J Duffin, “Geological Prophylactics in Petrus Christus' Painting A Goldsmith in his shop possibly Saint Eligius (1449) at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268687003; Hagen, op cit, at 48.

[3] Maryan W Ainsworth, with Maximiliaan Martens, Petrus Christus, Renaissance Master of Bruges, Exhibition Catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1994, 96 ff, at 98.

[4] Ainsworth, Petrus Christus, op cit, at 98.

[5] Ainsworth, Petrus Christus, op cit, at 98.

[6] Duffin, op cit.

[7] Hagen, op cit at 46; Duffin, op cit.

[8] Ainsworth, Petrus Christus, op cit, at 98.

[9] Hagen, op cit, at 46.

[10] Hugo van der Velden, “Defrocking St Eloy: Petrus Christus’s Vocational Portrait of a Goldsmith”, Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, Vol. 26, No. 4 (1998), pp. 242-276; Maryan W Ainsworth, “Intentional Alterations of Early Netherlandish Painting”, Essay in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, January 2008.

[11] Velden, op cit at 244.

[12] Velden, op cit at 246.

[13] Velden, op cit at 242.

[14] Velden, op cit at 257-261. See, for example, van Eyck’s portrait of prominent Bruges goldsmith Jan de Leeuwn (1436).

[15] Velden, op cit at 262.

[16] Maximiliaan Martens, in Ainsworth, Petrus Christus, op cit at 15

[17] Martens, op cit at 4ff. Christus would also have been attracted by the fact that the fee required to obtain citizenship (and therefore membership of the painters’ guild) had recently been reduced.

[18] Martens, op cit. On the growth of Antwerp, see our article Lost in Translation http://www.artinsociety.com/lost-in-translation-bruegelrsquos-tower-of-babel-new-page.html

© Philip McCouat, 2020.

RETURN TO HOME