Early influences of photography on art - Part 3

|

By Philip McCouat Pt 1: Initial impacts Pt 2: Photography as a working aid Pt 3: Photographic effects Pt 4: New approaches to “reality” |

More on photography

For other articles on photography, see: Art in a speeded-up world Why wasn’t photography invented earlier? ---------------------------------------------- |

Photographic effects

Having established that many painters used photography to some extent as a working resource, we now turn to the actual impacts that it may have had on the works they produced.

Cropping and the edge

It is certainly arguable that certain photographic qualities had specific compositional or stylistic influences [97]. As Johnson has pointed out, paintings in the western Renaissance tradition were typically contained and finite, a window onto the world in which a box of space, clearly defined by a non-intrusive framing edge, presented that world as calculable and whole [98]. In contrast, many photographs came to present a cropped appearance, either accidentally (as where a snapshot captures a part of a figure entering the scene), or deliberately (as where a photo is edited to highlight the action, draw the viewer into the scene, or even just to save space). Photographs can thus present a new world of fragmentary views based on discontinuous forms and unexpected juxtapositions that occur in nature, but which are edited out in adult human perception.For example, a photo of a pedestrian passing in front of a street lamp might make it appear as if the lamp was welded to his head [99].

This had two consequences. Firstly, the new framing edges, coupled with shorter exposure times, reinforced impressions of the “fleeting moment” of arrested motion, a spirit of temporality, momentariness or movement continuing beyond the frame into real space and time [99A]. This effect dramatically contradicted the contained and timeless quality of classical painting. Certainly, these features start appearing in many paintings – for example Toulouse-Lautrec’s At the Moulin Rouge (Fig 5) or Cassatt’s Mrs Cassatt Reading to her Grandchildren (1880). Such effects, of course, were not unprecedented. Back in the 17th century, Vermeer was able to create an analogous, but oddly paradoxical. effect of “being in the moment” in paintings such as Officer and Laughing Girl (ca 1657), by presenting believable people in deceptively understated and casual situations (as distinct from events) and providing sufficient context and detail to induce interest in the viewer while still leaving them uncertain as to exactly what is happening [99B].

This had two consequences. Firstly, the new framing edges, coupled with shorter exposure times, reinforced impressions of the “fleeting moment” of arrested motion, a spirit of temporality, momentariness or movement continuing beyond the frame into real space and time [99A]. This effect dramatically contradicted the contained and timeless quality of classical painting. Certainly, these features start appearing in many paintings – for example Toulouse-Lautrec’s At the Moulin Rouge (Fig 5) or Cassatt’s Mrs Cassatt Reading to her Grandchildren (1880). Such effects, of course, were not unprecedented. Back in the 17th century, Vermeer was able to create an analogous, but oddly paradoxical. effect of “being in the moment” in paintings such as Officer and Laughing Girl (ca 1657), by presenting believable people in deceptively understated and casual situations (as distinct from events) and providing sufficient context and detail to induce interest in the viewer while still leaving them uncertain as to exactly what is happening [99B].

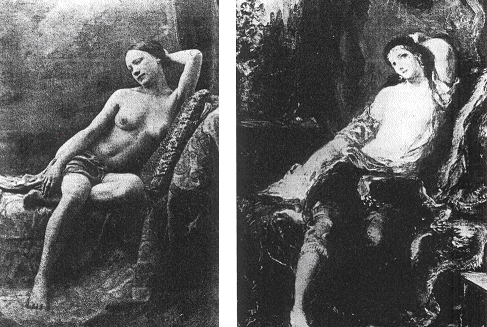

_ Secondly, though painters would traditionally avoid the incongruities in their compositions, “it was not long before men [sic] began to think photographically, and thus to see for themselves things that it had previously taken the photograph to reveal to their astonished and protesting eyes”[100]. This familiarisation led to what Varnedoe calls a “consensus of tolerance”, which he believes conditioned the public, and artists themselves, to accepting or even looking for unusual perspectives or features [101]. However, the effect of this can be overstated. Delacroix still felt it appropriate to soften the harsh perspective of his photographic model for Odalisque (1857) (compare Fig 6 and 7) [102]; and certainly little consensus of tolerance was evident in the initially hostile reaction to the Impressionist exhibitions [103].

_ Cropping can also tend to produce odd angles of perspective, such as aggressive abutments of near and distant zones [104]. This effect, which is exaggerated by the flattening effect of the camera is, of course, not exclusive to photography – as Galassi has pointed out, this was a trend that was already present in some pre-photographic era paintings [105]. It also forms a prominent part in many Japanese woodblock prints that were being “discovered” in Paris round 1870. As just one example, there is audacious cropping of boat and passenger, coupled with an extreme diagonal perspective, in Hiroshige’s Distant View of Kinryuzan Temple at Asakusa [106]. The cropping here is similar to that in Theodore Robinson’s Two in a Boat, which was certainly based on a photograph (the “squared up" photo exists), illustrating that similar effects can rise from different sources. In general, it is possible that both influences were “mutually reinforcing”, or possibly the prevalence of photography prepared the ground for a receptive attitude by painters to the idiosyncrasies of the Japanese prints [107].

Degas’ Place de la Concorde (Fig 8) illustrates the difficulty of drawing dogmatic or sweeping conclusions in this area.

Degas’ Place de la Concorde (Fig 8) illustrates the difficulty of drawing dogmatic or sweeping conclusions in this area.

The painting shows radical cropping, a spontaneous feel to the characters due to their unconventional positioning, and an unusual composition lacking any middle ground. Berger argues against a photographic influence, on the basis that no photographer would have taken such a picture at that time [108]. Instead, he claims, the unpeopled negative space in fact plays an important part in a carefully planned, overall composition, which reflects a dynamic and rhythmic equilibrium of patterns, which he says is characteristic of Japanese prints [109]. However, another strong possibility is that Degas’ method simply reflected his own personal approach to painting. For example, his Portrait of Diego Martelli, which also demonstrates typical “snapshot” characteristics of arbitrary cropping, immediacy and idiosyncratic viewpoint, was executed in 1879, before snapshot photography was widely available, and some 15 years before Degas himself acquired a camera.

This suggests that Degas’ so-called “Kodak eye” may have been operating even without the direct influence of photography [110]. Degas himself noted his predilection to “want to look through the keyhole”, an attitude likely to produce voyeur-like perspectives which could result in precisely the sharply angled viewpoints, unexpected juxtapositions, and abrupt cutting off of forms that characterised his art [111].

This suggests that Degas’ so-called “Kodak eye” may have been operating even without the direct influence of photography [110]. Degas himself noted his predilection to “want to look through the keyhole”, an attitude likely to produce voyeur-like perspectives which could result in precisely the sharply angled viewpoints, unexpected juxtapositions, and abrupt cutting off of forms that characterised his art [111].

Distinctive perspectives

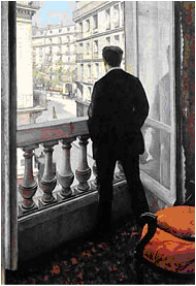

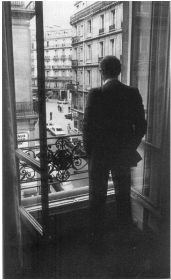

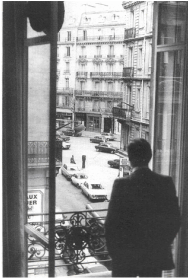

The unusual and “distorted” perspectives typical of some photography have also been credited with the idea for the seemingly exaggerated perspective of works by artists such as Caillebotte. Certainly there is convincing documentary evidence [112] that these perspectives are attributable to his use of wide-angle lens photographs in his preparatory sketches for paintings such as Paris Street; Rainy Weather (1877) and Young Man at his Window (Fig 9) [113].

_ Other photographic effects on perspective can also be identified. The distortions caused by extreme photographic close-ups were grotesquely reflected in Munch’s Double Portrait of the Painter Henrik Lund and his Wife Gunibjor (1905/6) [114]. The radical foreshortening in Caillebotte’s The Oarsmen (1877) is based on a photo taken by his brother Martial – a small squared drawing in pencil of the oarsmen on tracing paper has survived which has the same size as the usual measurements of glass negatives of that period [115]. Similarly, the extreme foreshortening of the corpse in Eakins’ The Gross Clinic presumably reflects the influence of the photographic studies with which the artist was deeply interested [116]. However, despite claims that such effects in Eakins’ work were “conceivable only after photography” [117], this type of foreshortening is obviously not always attributable to photography, and there are countless examples of pre-photographic paintings exhibiting the same effect – Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Nicolaes Tulp (1632) and Pozzo’s Entrance of St Ignatius into Paradise (1694) are two of many.

On a purely speculative note, it could also be observed that the effects created in wide angle, short focus photographic portraits seem to anticipate some of the distortionary effects of Cubism [118].

On a purely speculative note, it could also be observed that the effects created in wide angle, short focus photographic portraits seem to anticipate some of the distortionary effects of Cubism [118].

New viewpoints, new structures

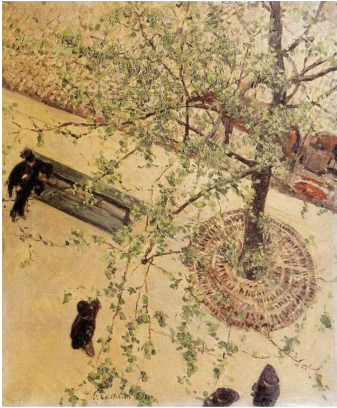

There have also been various attempts to link photography with the unusual overhead viewpoints adopted by Caillebotte in paintings such as Boulevard Seen From Above (Fig 9A). This question assumes some importance, as overhead perspectives, and a supposedly associated viewing of the world as a flat pattern, have been considered by some to be a significant characteristic of modern art [119].

One suggestion is that Caillebotte may have been influenced by the first aerial photographs taken by Nadar from a hot air balloon in 1858. However, this seems unlikely. In any event, painted or engraved aerial perspectives of cities had been known for centuries [120]. Furthermore, those views are imagined from very great heights, completely different from Caillebotte’s viewpoint.

One suggestion is that Caillebotte may have been influenced by the first aerial photographs taken by Nadar from a hot air balloon in 1858. However, this seems unlikely. In any event, painted or engraved aerial perspectives of cities had been known for centuries [120]. Furthermore, those views are imagined from very great heights, completely different from Caillebotte’s viewpoint.

Closer parallels may be found in the general topographical views of city streets from elevated viewpoints used by photographers to meet the demand for images of the vistas opened up by Haussmann’s new Paris [121]. However, caution is warranted before drawing a causative link from these to paintings such as Caillebotte’s. The photographer’s typical viewpoint in these topographic views was from the tops of buildings. Given that this is precisely where painters also typically had their studios – where the top-floor position was able to capture the maximum light – it is natural that they would adopt similar viewpoints when painting the new city vistas. Caillebotte explicitly used the viewpoint from his elevated studio on the Boulevard Haussmann in works such as Young Man at his Window, though as discussed previously, he probably used photography to dramatise its effect [122].

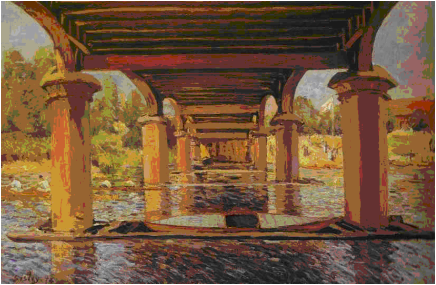

It was not only the viewpoint provided by Haussmann’s new structures that was novel, but also the way in which those structures themselves were viewed. The natural mode of recording these was photography, because of its speed, accuracy and flexibility, and its close association with engineering in general. One example is Sisley’s Under the Bridge at Hampton Court (Fig 10).

It was not only the viewpoint provided by Haussmann’s new structures that was novel, but also the way in which those structures themselves were viewed. The natural mode of recording these was photography, because of its speed, accuracy and flexibility, and its close association with engineering in general. One example is Sisley’s Under the Bridge at Hampton Court (Fig 10).

_ Rubin claims that this composition was “unthinkable” without Collard’s photographs from similar vantage points (Fig 11). As Rubin says, “the point is not that Sisley…. was imitating photographs; rather, it is that in these images where modern bridges themselves became the subject matter, the strategies for representing them were determined by engineering and photography”. Thus, he says, photography “must be credited with chronological priority and with introducing innovative angles and vantage points”[123].

_ However, not all artists adopted a photographic aesthetic when portraying these structures. Compare, for example, Caillebotte’s Pont de l’Europe with Renoir’s The Pont Neuf. Caillebotte’s more photographic approach stresses the stark structure of the bridge, and the glaring effect of light. Renoir’s more traditional approach is far more picturesque, nostalgic and full of narrative incident. However, the possibility remains that artists may not have taken to representations of modern structures so readily in any event, were it not for the pioneering role taken by photography, because of its role in inspiring artists to view these structures as worthy artistic subjects in the first place.

Distinctive effects of cartes

It also appears that some of the specific lighting and compositional features of cartes de visite may have found their way into some paintings.

For example, Munch’s Self Portrait with Cigarette and his colleague Strindberg’s carte de visite photo, which was in Munch’s possession, are both lit from below, with a resultant distortion of the subject’s features so the moustaches, mouths and eyes appear surprisingly alike. The effect is particularly striking as the painting and the carte are of different persons [124].

McCauley mounts a plausible case that both Monet and Renoir, in their early careers, created works that displayed the same flatness, full-length poses and use of standardised props that signal at least an awareness, if not direct copying, of carte de visite models. Monet’s commissioned portrait of Mme Gaudibert (1868) appears to be a painted adaptation of a carte, as evidenced by the use of standard carte props (drapery, an arbitrarily placed table bearing symmetrical flowers and a patterned carpet), the height from which the figure is viewed, the similarities in the turn of the head, the attention paid to the reflections and shadows cast by the massive satin train, the position of the figure on the canvas, the frontal lighting, the careful folding of the fingers to reduce the size of the hand, and the dress itself [125].

Manet also may have relied on cartes as a matter of course for studio portraits during 1870s and 1880s. McCauley suggests, for example, that Manet’s Portrait de M Pertuuset (1880/81) had its “obvious inspiration” in Disderi’s 1865 carte of that person [126]. It is also feasible that the harsh lighting effects and exaggerated chiaroscuro that were characteristic of the frequently-overlit cartes de visite may be detected in Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (1863). McCauley also suggests that the accouché pose common in many carte portraits – originally adopted because it helped keep the sitter still during exposure – became reflected in painted portraits [127]. In general, these suggestions are plausible, without necessarily being convincing.

For example, Munch’s Self Portrait with Cigarette and his colleague Strindberg’s carte de visite photo, which was in Munch’s possession, are both lit from below, with a resultant distortion of the subject’s features so the moustaches, mouths and eyes appear surprisingly alike. The effect is particularly striking as the painting and the carte are of different persons [124].

McCauley mounts a plausible case that both Monet and Renoir, in their early careers, created works that displayed the same flatness, full-length poses and use of standardised props that signal at least an awareness, if not direct copying, of carte de visite models. Monet’s commissioned portrait of Mme Gaudibert (1868) appears to be a painted adaptation of a carte, as evidenced by the use of standard carte props (drapery, an arbitrarily placed table bearing symmetrical flowers and a patterned carpet), the height from which the figure is viewed, the similarities in the turn of the head, the attention paid to the reflections and shadows cast by the massive satin train, the position of the figure on the canvas, the frontal lighting, the careful folding of the fingers to reduce the size of the hand, and the dress itself [125].

Manet also may have relied on cartes as a matter of course for studio portraits during 1870s and 1880s. McCauley suggests, for example, that Manet’s Portrait de M Pertuuset (1880/81) had its “obvious inspiration” in Disderi’s 1865 carte of that person [126]. It is also feasible that the harsh lighting effects and exaggerated chiaroscuro that were characteristic of the frequently-overlit cartes de visite may be detected in Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (1863). McCauley also suggests that the accouché pose common in many carte portraits – originally adopted because it helped keep the sitter still during exposure – became reflected in painted portraits [127]. In general, these suggestions are plausible, without necessarily being convincing.

Blurring and light effects

Photographic “blurring” can result from the combination of moving objects and (relatively) slower exposure times. Similar effects are occasionally reflected in paintings. In Munch’s photographically-based Man and Woman II, for example, a figure on the left stands out as a dynamic blurred shadow, as a result of moving away from a position “too close” to the camera [128]. It is also arguable that the “smudged” figures in Monet’s Boulevarde des Capucines are based on the blurred figures in an 1868 photo [129]. However, in the painting, unlike the photograph, everything is a bit blurred, not just the figures. Furthermore, the painted figures are actually recognisable as people, whereas the photographed figures do not look like people at all [130].

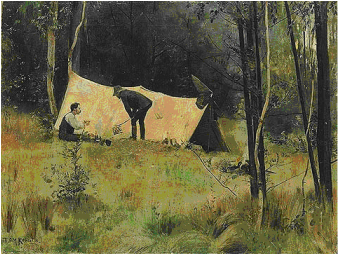

Once longer focus lengths became possible, photos started exhibiting different levels of focus in the one scene, with a resultant blurring effect. It appears that this characteristic was adopted in some paintings of Tom Roberts and Frederick McCubbin, both of whom were closely involved with photography. For example, Roberts’ Artists’ Camp (Fig 12) and McCubbin’s The Lost Child and Down on his Luck, all from the 1880s, exhibit sharply defined foreground trees, twigs and leaves, with a rather diffuse background very characteristic of photographic “haze” [131]. Effectively, there are two planes of vision, with differential focus.

Once longer focus lengths became possible, photos started exhibiting different levels of focus in the one scene, with a resultant blurring effect. It appears that this characteristic was adopted in some paintings of Tom Roberts and Frederick McCubbin, both of whom were closely involved with photography. For example, Roberts’ Artists’ Camp (Fig 12) and McCubbin’s The Lost Child and Down on his Luck, all from the 1880s, exhibit sharply defined foreground trees, twigs and leaves, with a rather diffuse background very characteristic of photographic “haze” [131]. Effectively, there are two planes of vision, with differential focus.

_ Blurring or hazy impressions can also result from the atmospheric light effects that photographs can produce. Johnson has suggested that the transformation of a world in full colour into “powerful effects of light and shadow” must have been compelling to painters traditionally more attentive to chiaroscuro than to hue [132]. Corot, for example, moved from an early style based on architectural structure, hard edged linearity and geometrically based formal relationships, into an overwhelming concern with light effects, softness, and the dematerialisation of the earlier solidity of his forms. Johnson argues that this is “impossible” to explain without the precedent of the paper photograph and, particularly, the effects of halation [133]. This photographic impression is emphasised by the fact that many of his paintings were done in a muted silvery grey [134].

It is interesting too that the emergence of Seurat’s pointillist style is reminiscent of the almost contemporaneous invention of “half-tone” photography in 1880 [135].

It is interesting too that the emergence of Seurat’s pointillist style is reminiscent of the almost contemporaneous invention of “half-tone” photography in 1880 [135].

Other photographic "defects"

Other photographic defects may also have had their effects.

Early photography tended to make blues paler, pushed green and red towards

black and had difficulty capturing delicate shades of white [136]. The tendency

of early photographs to show dark green as black is reflected, for example, in

the stark contrast of foreground foliage in Bierstadt’s

photographically-derived Rocky Mountains

(1863) (Fig 13). The washed out backdrop in this work also mirrors the fact

that setting a correct photographic exposure for foreground detail tended to

leave the background badly underexposed [137].

This problem was sometimes sought to be solved by “combination” printing, in which two or even more separate negatives were used to create the one photographic print. However this also could create problems if the scales of the components were not properly matched. So, in Dyce’s Highland Ferryman (1858), a painting for which there is documentary evidence of a photographic origin, the detail of the area beyond the river and the hillside and mountain in the distance is disproportionately tiny in relation to the foreground [138]. It is also possible that the use of composite photographs as sources contributed to the lack of depth in paintings such as Millais’ Spring (Apple Blossom), which gives the impression of bas reliefs, with cut out figures against stage-like flat backdrops [139].

Although the photographic effect/defect of double exposure was probably discovered accidentally in about 1850, it was later used cynically to produce “spirit” photographs which purported to show living people with beloved dead relatives usually hovering behind them [140]. This contributed enormously to the rise of belief in spiritualism and “the other side” which had first surfaced in Germany back in the 1840s [141]. The belief that communication with the departed might be possible was in many ways quite understandable in the late nineteenth century, given the recent developments of other “invisible” and seemingly impossible modes of communication such as the telephone and the telegraph [142]. Munch, a keen student of photographic effects, seems to have been directly influenced by these extraordinary ghostly images in his Sick Child (Study) and The Storm 1893 [143].

These types of image also found artistic expression in the development of “fairy” paintings. These paintings became enormously popular for a short period in Victorian England. They displayed miniaturised evanescent creatures of mythology, populating a pristine landscape, visualised in the obsessive reality demanded by the “truth to nature” doctrine that had also gripped the Pre-Raphaelites [144]. However, just as photography had played a part in their rapid rise, the later revelations that spirit photographers had engaged in deliberate fakery and fraud also contributed to their equally rapid decline [145].

Go now to Part 4 "New Approaches to reality"

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015

We welcome your comments on this article

Although the photographic effect/defect of double exposure was probably discovered accidentally in about 1850, it was later used cynically to produce “spirit” photographs which purported to show living people with beloved dead relatives usually hovering behind them [140]. This contributed enormously to the rise of belief in spiritualism and “the other side” which had first surfaced in Germany back in the 1840s [141]. The belief that communication with the departed might be possible was in many ways quite understandable in the late nineteenth century, given the recent developments of other “invisible” and seemingly impossible modes of communication such as the telephone and the telegraph [142]. Munch, a keen student of photographic effects, seems to have been directly influenced by these extraordinary ghostly images in his Sick Child (Study) and The Storm 1893 [143].

These types of image also found artistic expression in the development of “fairy” paintings. These paintings became enormously popular for a short period in Victorian England. They displayed miniaturised evanescent creatures of mythology, populating a pristine landscape, visualised in the obsessive reality demanded by the “truth to nature” doctrine that had also gripped the Pre-Raphaelites [144]. However, just as photography had played a part in their rapid rise, the later revelations that spirit photographers had engaged in deliberate fakery and fraud also contributed to their equally rapid decline [145].

Go now to Part 4 "New Approaches to reality"

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015

We welcome your comments on this article

End Notes for Part 3

97. At a superficial level, of course, the composition of a photograph could simply be copied in a painting. Conversely, some painters, including Corot, Rousseau and Millet, sometimes used the technique of cliché-verre, which entailed drawing directly on a collodion- or smoke-covered glass plate and printing the plate by exposing it to light against sensitized paper.

98. Johnson, op cit at 88.

99. Many of the photographic studies for artists, discussed earlier, also strayed into extreme casualness or oddly-cropped compositions of a type that fell outside traditional conceptions.

99A. All these comments apply even more so to movie films, which essentially consist of thousands of individual photographs which, although being sequential overall, individually can look almost random.

99B. See generally Anne Hollander, Moving Pictures, Harvard University Press, 1991, p140 ff.

100. Ivins, W M Jnr, Prints and Visual Communication, Cambridge Mass., Harvard University Press 1953 at p 180. Hockney, op cit, describes this as the return of “awkwardness”.

101. Varnedoe, K, “The Artifice of Candor: Impressionism and Photography Reconsidered” in Art in America, January 1980, 66 at 69.

102. Koetzle, op cit at 35.

103. Similarly, critics were wildly divided over whether Caillebotte’s perspectives were “insane” or “true”, and his uncompromising frontal perspective in The Oarsmen (1878) still looks odd even to modern eyes.

104. Johnson, op cit at 89.

105. Galassi, op cit at 18ff.

106. Scharf, op cit, also cites Hiroshige’s The Haneda Ferry and Benten Shrine (1858) in this connection.

107. Scharf, op cit at 198. Similarly, Johnson (op cit at 78) suggests that, “without the precedent of photography, it is unlikely that the Japanese print…would have captured western artistic imagination as significantly as it did”.

108. Berger, K, Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse, CUP, Cambridge 1992, at 56. Varnedoe adds the qualification that every time Canaletto set up his camera obscura in the Piazza san Marco he saw Degas’ newspaper carrier walk by, but he did not choose to paint him – thus, it is not simply what is available that shapes art, but what and artist chooses to find meaningful (Varnedoe, K, A Fine Disregard: What Makes Modern Art Modern, Thames and Hudson, London, 1990 at 34).

109. A similar point could be made in relation to the cropping and open spaces in Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Weather (1877). Caillebotte too was interested in Japanese prints. However, it is also arguable that, in this painting, the effect is accentuated by the exaggerated perspective— discussed further in the text – and the studied order of the few people in the square.

100. This suggestion is strengthened by the fact that the apparently negligent and spontaneous pose of the sitter was the end-result of at least six working drawings: see Smith, G, “Edgar Degas and Diego Martelli” in History of Photography 1991 v 15 no 2, Spring, p 45-46. Incidentally, the brand name “Kodak” was deliberately chosen to suggest the abrupt click of a snapshot (Nead, L, The Haunted Gallery, Yale University Press, New Haven/London, 2007 at 112).

111. See also Rubin, op cit at 47. The vertical cutting off of a person on the left hand edge of Place de la Concorde is similar to the cropping of the figure on the right in Paris Street/Rainy Weather (1877) by Caillebotte, a painter who, as we shall see, was undoubtedly photographically influenced. But perhaps this simply demonstrates that similar effects can result from different causes.

112. Varnedoe, K, Gustave Caillebotte Yale UP, New Haven and London 1987 p20ff, 187. An exhibition held at Lausanne in 2005 was dedicated to the works of Caillebotte and their relationship to the photographic work of his brother, Martial (Fondation de L’Hermitage: “Caillebotte at the Heart of Impressionism”, June-October 2005).

113. Caillebotte’s Pont de l’Europe (Fig 31) is another obvious example. Zola criticised such paintings as “anti-artistic” because of their “middle class exactitude”. Of course, it is possible to argue, at a stretch, that Caillebotte was instead inspired by Japanese prints, in which he took a particular interest, and simply used photography to achieve the effects which those prints inspired him to achieve.

114. Eggum, op cit at 78-79.

115. Hanson, D, “Newly discovered Prints by Gustave Caillebotte”, The Burlington Magazine No 1272, Vol CLI, Mar 2009.

116. Jacobsen, op cit at 73. Infrared techniques show that Eakins was projecting the photographic images onto his painting supports in order to make his underdrawings.

117. Lewis, M, “The Realism of Thomas Eakins”, New Criterion.

118. The photographs in Fig 26 and 27 were published in Photographische Rundshau in 1902 and reproduced in Eggum, op cit at 79.

119. Hughes, R, The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Change, Thames and Hudson, London 1991 (revd edn) at 34; Varnedoe, (Fine Disregard), op cit at 217.

120. For example, View of Venice (c. 1500) by Jacopo de’ Barberi; or Richard Horwood’s amazingly detailed aerial view of London and Southwark, “shewing every house” (1799).

121. Rubin, op cit at 42: Spate, V, Claude Monet: The Colour of Time,Thames and Hudson, London 1992 at 46. Scharf also likens Caillebotte’s A Pedestrian Island: Boulevarde Haussman (c 1880) to a photograph by Jouvin of the Monument at the Place des Victoires. However Caillebotte’s viewpoint is more plunging and dramatic. In addition, unlike Jouvin’s work, it does not portray anything in particular – it appears to be observation for its own sake, rather than for the significance of the subject (Rubin, op cit at 50).

122. The bird’s eye viewpoint adopted in many Japanese woodblock prints also cannot be discounted as an influence.

123. Rubin, op cit at 42, 43.

124. Eggum, op cit at 60.

125. McCauley, op cit at 195. Monet, however, leaves his mark in the direct, caricatural light and dark brushstrokes.

126. McCauley, op cit at 190.

127. McCauley, op cit at 143.

128. Eggum, op cit at 157.Of course, this is not to say that before photography artists were not aware of the perceptual blurring created by movement. For example, the blurring effect caused by a rapidly spinning wheel is clearly evident in Velasquez’ The Spinners, painted back in 1648. However, in a photograph this is made much more explicit because it is a fixed image.

129. Scharf, op cit at 168. The critic Louis Leroy rather uncharitably attacked this painting for its representation of figures on the street as “black tongue-lickings” (Rubin, op cit at 45).

130. Varnedoe, (Artifice) op cit at 70. Incidentally, the quasi Impressionist blurring effect seen in modern reproductions of Niepce’s original heliograph (View from the Window at Le Gras, ca 1826) is misleading – this effect is actually due to the reproduction process and is not present in the original (see University of Texas website at www.hrc.utexas.edu/exhibitions/permanent/wfp).

131. Gaskins, op cit at 364. Tuffelli detects a similar effect in Manet’s The Luncheon in the Studio (Fig 4), commenting that this painting, “with its figure in the foreground – framed, as it were, in a medium close shot – painted with meticulous attention to detail in contrast with the blurred background, shows a definite photographic influence” (Tuffelli, N, Nineteenth-Century French Art 1848-1905, Chambers, Edinburgh, 2004, at 29). On this painting see also note 18.

132. Johnson, op cit at 90, 91.

133. Photographic halation occurred when light acting on the emulsion also struck the uncoated side of the glass and was refracted back through the emulsion, causing a redevelopment or erosion of dark areas. It can for example, lead to a halo of light with consequent blurring ethereal effects.

134. Similar photographic colour ranges can be detected in works by Ingres (La Comtesse d’Haussonville (1845)) (see note 49), though, of course monotonal studies were hardly unique to the photographic era. Eggum notes a temporary fashion for sepia paintings among some Norwegian painters in the 1870s (Eggum, op cit at 17).

135. The half tone process reduces a photograph to a collection of dots. Its invention, although commonly overlooked, was revolutionary, as it enabled photographs to be reproduced in a magazine or newspaper. Seurat’s style is, of course, more commonly attributed to his well-known interest in developments in optics. However it is suggestive that, unlike a normal photograph which can get more detailed the closer one gets to it, the image presented by a half tone (or a Seurat painting) can only be perceived at a distance – the more it is magnified, the more it dissolves and the less “real” it appears.

136. McCauley, op cit at 194.

137. Lindquist-Cock, E M, Influence of Photography on American Landscape Painting 1839-1880, Garland Pub, New York, 1977. Similarly, in photography of the 1850s and 60s, “the impossibility of obtaining a harmonious fusion of sky and landscape was a general complaint” (Gernsheim, H, The Rise of Photography 1850-1880, Thames and Hudson, London, 1981 at 78). Skies tended to emerge as blanks because their greater luminosity in comparison with the land resulted in overexposure.

138. Willsdon, C, “Dyce ‘in Camera’: New Evidence of his Working Methods”, Burlington Magazine 132/1052 (Nov 1990) 760. On the other hand, as we have seen, photography’s merging of colour tones could enable it to reveal faults in painting that were not apparent in the originals, for example by revealing a deviation of form hidden in the original under the surface charm of colour.

139. Alternatively, this appearance resembles the effect achieved when looking through binoculars.

140. Eggum, op cit at 32.

141. Further impetus to this movement was provided by the horrific death tolls in the American Civil War, the Franco Prussian War and the Paris Commune. In many cases, photographs became grieving families’ only tangible link with their departed ones. The appeal to such people of photographs that seemed to show those persons as still “living” is obvious.

142. Jolly, M, Faces of the Living Dead: the Belief in Spirit Photography, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2006 at 8. Jolly also makes the point that photography stops an image of a living person dead in its tracks, and peels that frozen image way from them. In this sense, all portrait photographs are spirit photographs because they allow us to see people as they lived in the past.

143. Eggum, op cit at 32.

144. Examples include Richard Dadd’s The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke (1855-64); Joseph Noel Paton’s The Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania (1847) and John Anster Fitzgerald’s The Captive Dreamer (1856) (Maas, op cit at 148-9).

145. Maas, op cit at 204.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013

Back to Pt 1: Initial impacts

Back to Pt 2: Photography as a working aid

Pt 4: New approaches to “reality”

Citation: McCouat, P, "Early influences of photography on art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home

98. Johnson, op cit at 88.

99. Many of the photographic studies for artists, discussed earlier, also strayed into extreme casualness or oddly-cropped compositions of a type that fell outside traditional conceptions.

99A. All these comments apply even more so to movie films, which essentially consist of thousands of individual photographs which, although being sequential overall, individually can look almost random.

99B. See generally Anne Hollander, Moving Pictures, Harvard University Press, 1991, p140 ff.

100. Ivins, W M Jnr, Prints and Visual Communication, Cambridge Mass., Harvard University Press 1953 at p 180. Hockney, op cit, describes this as the return of “awkwardness”.

101. Varnedoe, K, “The Artifice of Candor: Impressionism and Photography Reconsidered” in Art in America, January 1980, 66 at 69.

102. Koetzle, op cit at 35.

103. Similarly, critics were wildly divided over whether Caillebotte’s perspectives were “insane” or “true”, and his uncompromising frontal perspective in The Oarsmen (1878) still looks odd even to modern eyes.

104. Johnson, op cit at 89.

105. Galassi, op cit at 18ff.

106. Scharf, op cit, also cites Hiroshige’s The Haneda Ferry and Benten Shrine (1858) in this connection.

107. Scharf, op cit at 198. Similarly, Johnson (op cit at 78) suggests that, “without the precedent of photography, it is unlikely that the Japanese print…would have captured western artistic imagination as significantly as it did”.

108. Berger, K, Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse, CUP, Cambridge 1992, at 56. Varnedoe adds the qualification that every time Canaletto set up his camera obscura in the Piazza san Marco he saw Degas’ newspaper carrier walk by, but he did not choose to paint him – thus, it is not simply what is available that shapes art, but what and artist chooses to find meaningful (Varnedoe, K, A Fine Disregard: What Makes Modern Art Modern, Thames and Hudson, London, 1990 at 34).

109. A similar point could be made in relation to the cropping and open spaces in Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Weather (1877). Caillebotte too was interested in Japanese prints. However, it is also arguable that, in this painting, the effect is accentuated by the exaggerated perspective— discussed further in the text – and the studied order of the few people in the square.

100. This suggestion is strengthened by the fact that the apparently negligent and spontaneous pose of the sitter was the end-result of at least six working drawings: see Smith, G, “Edgar Degas and Diego Martelli” in History of Photography 1991 v 15 no 2, Spring, p 45-46. Incidentally, the brand name “Kodak” was deliberately chosen to suggest the abrupt click of a snapshot (Nead, L, The Haunted Gallery, Yale University Press, New Haven/London, 2007 at 112).

111. See also Rubin, op cit at 47. The vertical cutting off of a person on the left hand edge of Place de la Concorde is similar to the cropping of the figure on the right in Paris Street/Rainy Weather (1877) by Caillebotte, a painter who, as we shall see, was undoubtedly photographically influenced. But perhaps this simply demonstrates that similar effects can result from different causes.

112. Varnedoe, K, Gustave Caillebotte Yale UP, New Haven and London 1987 p20ff, 187. An exhibition held at Lausanne in 2005 was dedicated to the works of Caillebotte and their relationship to the photographic work of his brother, Martial (Fondation de L’Hermitage: “Caillebotte at the Heart of Impressionism”, June-October 2005).

113. Caillebotte’s Pont de l’Europe (Fig 31) is another obvious example. Zola criticised such paintings as “anti-artistic” because of their “middle class exactitude”. Of course, it is possible to argue, at a stretch, that Caillebotte was instead inspired by Japanese prints, in which he took a particular interest, and simply used photography to achieve the effects which those prints inspired him to achieve.

114. Eggum, op cit at 78-79.

115. Hanson, D, “Newly discovered Prints by Gustave Caillebotte”, The Burlington Magazine No 1272, Vol CLI, Mar 2009.

116. Jacobsen, op cit at 73. Infrared techniques show that Eakins was projecting the photographic images onto his painting supports in order to make his underdrawings.

117. Lewis, M, “The Realism of Thomas Eakins”, New Criterion.

118. The photographs in Fig 26 and 27 were published in Photographische Rundshau in 1902 and reproduced in Eggum, op cit at 79.

119. Hughes, R, The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Change, Thames and Hudson, London 1991 (revd edn) at 34; Varnedoe, (Fine Disregard), op cit at 217.

120. For example, View of Venice (c. 1500) by Jacopo de’ Barberi; or Richard Horwood’s amazingly detailed aerial view of London and Southwark, “shewing every house” (1799).

121. Rubin, op cit at 42: Spate, V, Claude Monet: The Colour of Time,Thames and Hudson, London 1992 at 46. Scharf also likens Caillebotte’s A Pedestrian Island: Boulevarde Haussman (c 1880) to a photograph by Jouvin of the Monument at the Place des Victoires. However Caillebotte’s viewpoint is more plunging and dramatic. In addition, unlike Jouvin’s work, it does not portray anything in particular – it appears to be observation for its own sake, rather than for the significance of the subject (Rubin, op cit at 50).

122. The bird’s eye viewpoint adopted in many Japanese woodblock prints also cannot be discounted as an influence.

123. Rubin, op cit at 42, 43.

124. Eggum, op cit at 60.

125. McCauley, op cit at 195. Monet, however, leaves his mark in the direct, caricatural light and dark brushstrokes.

126. McCauley, op cit at 190.

127. McCauley, op cit at 143.

128. Eggum, op cit at 157.Of course, this is not to say that before photography artists were not aware of the perceptual blurring created by movement. For example, the blurring effect caused by a rapidly spinning wheel is clearly evident in Velasquez’ The Spinners, painted back in 1648. However, in a photograph this is made much more explicit because it is a fixed image.

129. Scharf, op cit at 168. The critic Louis Leroy rather uncharitably attacked this painting for its representation of figures on the street as “black tongue-lickings” (Rubin, op cit at 45).

130. Varnedoe, (Artifice) op cit at 70. Incidentally, the quasi Impressionist blurring effect seen in modern reproductions of Niepce’s original heliograph (View from the Window at Le Gras, ca 1826) is misleading – this effect is actually due to the reproduction process and is not present in the original (see University of Texas website at www.hrc.utexas.edu/exhibitions/permanent/wfp).

131. Gaskins, op cit at 364. Tuffelli detects a similar effect in Manet’s The Luncheon in the Studio (Fig 4), commenting that this painting, “with its figure in the foreground – framed, as it were, in a medium close shot – painted with meticulous attention to detail in contrast with the blurred background, shows a definite photographic influence” (Tuffelli, N, Nineteenth-Century French Art 1848-1905, Chambers, Edinburgh, 2004, at 29). On this painting see also note 18.

132. Johnson, op cit at 90, 91.

133. Photographic halation occurred when light acting on the emulsion also struck the uncoated side of the glass and was refracted back through the emulsion, causing a redevelopment or erosion of dark areas. It can for example, lead to a halo of light with consequent blurring ethereal effects.

134. Similar photographic colour ranges can be detected in works by Ingres (La Comtesse d’Haussonville (1845)) (see note 49), though, of course monotonal studies were hardly unique to the photographic era. Eggum notes a temporary fashion for sepia paintings among some Norwegian painters in the 1870s (Eggum, op cit at 17).

135. The half tone process reduces a photograph to a collection of dots. Its invention, although commonly overlooked, was revolutionary, as it enabled photographs to be reproduced in a magazine or newspaper. Seurat’s style is, of course, more commonly attributed to his well-known interest in developments in optics. However it is suggestive that, unlike a normal photograph which can get more detailed the closer one gets to it, the image presented by a half tone (or a Seurat painting) can only be perceived at a distance – the more it is magnified, the more it dissolves and the less “real” it appears.

136. McCauley, op cit at 194.

137. Lindquist-Cock, E M, Influence of Photography on American Landscape Painting 1839-1880, Garland Pub, New York, 1977. Similarly, in photography of the 1850s and 60s, “the impossibility of obtaining a harmonious fusion of sky and landscape was a general complaint” (Gernsheim, H, The Rise of Photography 1850-1880, Thames and Hudson, London, 1981 at 78). Skies tended to emerge as blanks because their greater luminosity in comparison with the land resulted in overexposure.

138. Willsdon, C, “Dyce ‘in Camera’: New Evidence of his Working Methods”, Burlington Magazine 132/1052 (Nov 1990) 760. On the other hand, as we have seen, photography’s merging of colour tones could enable it to reveal faults in painting that were not apparent in the originals, for example by revealing a deviation of form hidden in the original under the surface charm of colour.

139. Alternatively, this appearance resembles the effect achieved when looking through binoculars.

140. Eggum, op cit at 32.

141. Further impetus to this movement was provided by the horrific death tolls in the American Civil War, the Franco Prussian War and the Paris Commune. In many cases, photographs became grieving families’ only tangible link with their departed ones. The appeal to such people of photographs that seemed to show those persons as still “living” is obvious.

142. Jolly, M, Faces of the Living Dead: the Belief in Spirit Photography, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2006 at 8. Jolly also makes the point that photography stops an image of a living person dead in its tracks, and peels that frozen image way from them. In this sense, all portrait photographs are spirit photographs because they allow us to see people as they lived in the past.

143. Eggum, op cit at 32.

144. Examples include Richard Dadd’s The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke (1855-64); Joseph Noel Paton’s The Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania (1847) and John Anster Fitzgerald’s The Captive Dreamer (1856) (Maas, op cit at 148-9).

145. Maas, op cit at 204.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013

Back to Pt 1: Initial impacts

Back to Pt 2: Photography as a working aid

Pt 4: New approaches to “reality”

Citation: McCouat, P, "Early influences of photography on art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home