Forgotten women artists

#2 Jane Loudon: artist, futurist, horticulturist and author

By Philip McCouat See readers’ comments

Introduction

Jane Loudon, born at the dawn of the 19th century, would come to have three major, bizarrely contrasting, achievements in her life. At age 20, she would become the author of the first fictional book on Mummies, starting a vast literary genre that has survived and prospered to the present day. A generation later, she would be responsible for introducing the pastime of gardening to the middle classes, with the publication of the first popular gardening manuals. And finally, she transformed herself yet again into a self-taught, acclaimed botanical artist.

In this article, the second in our series of Forgotten Women Artists, we look at Jane Loudon’s extraordinarily productive life.

In this article, the second in our series of Forgotten Women Artists, we look at Jane Loudon’s extraordinarily productive life.

Birth of The Mummy!

Jane C Loudon (née Webb) was born into a wealthy Birmingham family in 1807 [1]. After the early death of her mother in 1819, Jane travelled overseas for a year with her father, gaining familiarity with several languages. But shortly after, her father suffered some heavy business reverses, and the family’s fortunes rapidly declined. With his death soon after in 1824, Jane unexpectedly found herself both penniless and an orphan at only 17.

Fortunately, she had the benefit of an excellent education, and had the support of family friends such as the artist John Martin. She had already shown some promise as a poet, so she decided to embark on a writing career to support herself. Within two years she had published a book Prose and Verse (1826) and a year later, still aged only 20, produced her first major work, The Mummy! Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century (1827).

Fortunately, she had the benefit of an excellent education, and had the support of family friends such as the artist John Martin. She had already shown some promise as a poet, so she decided to embark on a writing career to support herself. Within two years she had published a book Prose and Verse (1826) and a year later, still aged only 20, produced her first major work, The Mummy! Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century (1827).

Jane’s book The Mummy!, which she described as her “strange, wild novel”, Is generally regarded as one of the pioneering works of science fiction and the first identifiable ancestor of the mummy genre [2]. It opens in 2126, when, after several revolutions in social, religious and political thought, England is at peace, a religious matriarchy under the rule of the Queen Claudia. Far from being dystopian, it is “a happy, egalitarian society filled with advances in technology, society and fashion: a peaceful world ruled by a female sovereign…”[3].

Against this background, a thwarted aristocrat decides to achieve fame by the ultimate scientific experiment – the recreation of life by the successful reanimation of a corpse. His chosen target is the mummy of the ancient Pharaoh Cheops, so he travels to Egypt. With the aid of galvanic stimulation, Cheops is revived, escapes from his Egyptian tomb and travels to England by balloon, where he crash-lands, accidentally killing Queen Claudia (!), and proceeds to involve himself, often quite cannily, in political affairs.

The story, unlikely as it is, had a number of inspirations. The public’s interest in mummies and ancient Egypt generally was already very high, largely as a result of the spectacular research publications emerging from Napoleon’s invasion of that country, the craze for mummy unwrappings, and the advent of fashionable tourism there (see our article on Mummy Brown).

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which had been published only nine years before, was also an obvious influence (see article on Frankenstein). Both works were created, most unusually, by very young women, and both feature the sensational re-animation of a dead body by an experimenter obsessed by discovering the secrets of life and death [4]. The setting of the novel in the distant future, together with predictions of what life would be like there, also has parallels with Shelley’s The Last Man (1826).

But Loudon’s technology-influenced and quite optimistic approach is far removed from Shelley’s, to such an extent that it can almost be regarded as a critique or parody. Loudon adopts a far lighter tone, as distinct from the grim terrors of Shelley’s creations. Loudon is also more interested in the technical and social advances that she predicts – the use of a galvanic battery in reanimation, the concept of space travel, court ladies in trousers, strange contraptions such as steam-powered surgeons and lawyers, and the delivery of letters by cannonballs.

The success of her book, and the novelty of her inventions – notably a steam-driven plough -- attracted the attention of the well-regarded agricultural and horticultural writer John Claudius Loudon. He requested an introduction to the author to discuss it further. It was this fateful meeting that would decide the next, totally different, phase of Jane’s life.

Against this background, a thwarted aristocrat decides to achieve fame by the ultimate scientific experiment – the recreation of life by the successful reanimation of a corpse. His chosen target is the mummy of the ancient Pharaoh Cheops, so he travels to Egypt. With the aid of galvanic stimulation, Cheops is revived, escapes from his Egyptian tomb and travels to England by balloon, where he crash-lands, accidentally killing Queen Claudia (!), and proceeds to involve himself, often quite cannily, in political affairs.

The story, unlikely as it is, had a number of inspirations. The public’s interest in mummies and ancient Egypt generally was already very high, largely as a result of the spectacular research publications emerging from Napoleon’s invasion of that country, the craze for mummy unwrappings, and the advent of fashionable tourism there (see our article on Mummy Brown).

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which had been published only nine years before, was also an obvious influence (see article on Frankenstein). Both works were created, most unusually, by very young women, and both feature the sensational re-animation of a dead body by an experimenter obsessed by discovering the secrets of life and death [4]. The setting of the novel in the distant future, together with predictions of what life would be like there, also has parallels with Shelley’s The Last Man (1826).

But Loudon’s technology-influenced and quite optimistic approach is far removed from Shelley’s, to such an extent that it can almost be regarded as a critique or parody. Loudon adopts a far lighter tone, as distinct from the grim terrors of Shelley’s creations. Loudon is also more interested in the technical and social advances that she predicts – the use of a galvanic battery in reanimation, the concept of space travel, court ladies in trousers, strange contraptions such as steam-powered surgeons and lawyers, and the delivery of letters by cannonballs.

The success of her book, and the novelty of her inventions – notably a steam-driven plough -- attracted the attention of the well-regarded agricultural and horticultural writer John Claudius Loudon. He requested an introduction to the author to discuss it further. It was this fateful meeting that would decide the next, totally different, phase of Jane’s life.

Gardening for the masses

Fig 3: Portrait of John Claudius Loudon

Fig 3: Portrait of John Claudius Loudon

John Loudon’s expression of interest in The Mummy! was no doubt made in the belief that its anonymous author was a man. So, as Jane later wrote, “It may easily be supposed that he was surprised to find the author of the book a woman”. The meeting, however, proved productive in an unexpected way. Here’s Jane again, “I believe that from that evening he formed an attachment to me, and, in fact, we were married on the 14th of the following September”[5].

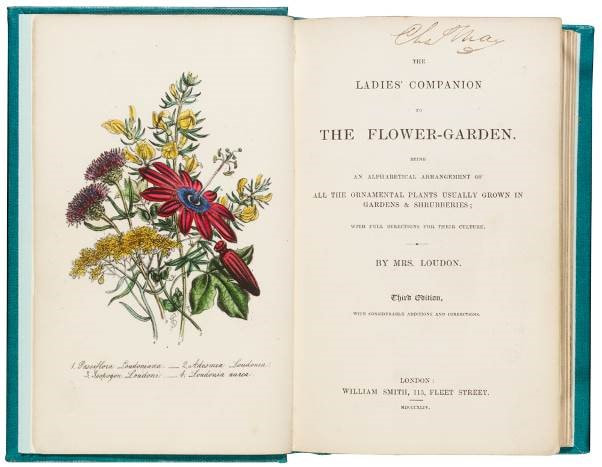

Despite having no previous experience in botany, Jane threw herself into assisting in her much older husband’s work as a botanist and garden designer. She planted and tended their extensive gardens in the meticulous manner that John needed for his research, and assisted in editing his rather technical publications, in particular his monumental Encyclopedia of Gardening (1834). But Jane came to believe that there was also a major gap in the market. She saw a need for gardening manuals, plainly written, directed at the growing middle classes (women in particular). With encouragement from prominent horticulturist John Lindley, she set about fulfilling that need with a series of books, with titles such as Gardening for Ladies.(1843), The Ladies’ Country Companion (1845) and The Ladies’ Companion to the Flower-Garden.

Despite having no previous experience in botany, Jane threw herself into assisting in her much older husband’s work as a botanist and garden designer. She planted and tended their extensive gardens in the meticulous manner that John needed for his research, and assisted in editing his rather technical publications, in particular his monumental Encyclopedia of Gardening (1834). But Jane came to believe that there was also a major gap in the market. She saw a need for gardening manuals, plainly written, directed at the growing middle classes (women in particular). With encouragement from prominent horticulturist John Lindley, she set about fulfilling that need with a series of books, with titles such as Gardening for Ladies.(1843), The Ladies’ Country Companion (1845) and The Ladies’ Companion to the Flower-Garden.

The venture would prove to be spectacularly successful – and influential. The books, enlivened by Jane’s accounts of her own gardening projects, sold in their thousands and ran through multiple editions [6]. Jane “was to Victorian gardening what Mrs Beeton was to cookery… women all over the country were enthused enough by [her books] to take up gardening as a hobby” [7]. The Loudons came to be regarded as among the leading horticulturists of the day, mixing in social circles with literary identities such as Charles Dickens and William Makepiece Thackeray. They also travelled widely to inspect botanic gardens, in the process becoming early adopters of garden tourism.

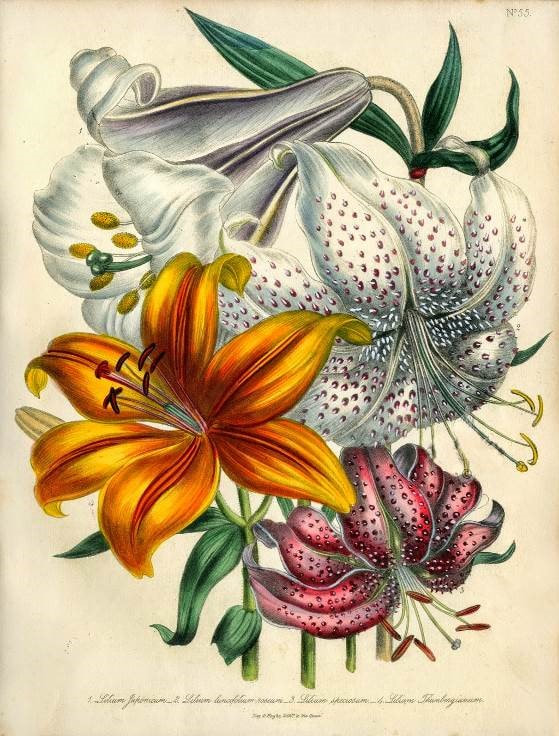

It was quite early in the course of this new career that Jane realised the importance of illustrations in conveying information to her readers. Her response was typical -- she decided to teach herself to paint.

It was quite early in the course of this new career that Jane realised the importance of illustrations in conveying information to her readers. Her response was typical -- she decided to teach herself to paint.

Becoming an artist

Jane’s first efforts were limited to sketches, but she progressed quickly as her skills and experience grew.

Her typical style, which involved grouping the flowers to form bouquets, made her designs popular to copy as well as being used for decoupage on trays, lampshades and tables. [8]. However, many of her most accomplished works feature just one variety. She also made full use of the new technique of chromolithography which made print production much faster and enabled her to increase her output.

Decline and fall

From this high point, however, Jane’s fortunes steadily declined. Her husband John died early, after a business failure involving his planned massive publishing project, the Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum. In a striking echo of her teenage experience with her father, Jane found herself single and in financial difficulties. To compound the situation, she had a 12-year-old daughter to care for [9], and lost the post she had as editor of The Ladies' Companion at Home and Abroad magazine. With her books declining in sales due to competition, and despite an annual pension of £100 from the Civil List, Jane died almost penniless in 1858, aged only 51.

Jane’s life was relatively short but, in its own idiosyncratic way, spectacular. She had the rare ability to generate new ideas in totally different fields. She showed considerable tenacity in successfully carrying them through, and an impressive capacity to reinvent herself creatively. But the early deaths of both her parents and her husband, and the two major financial reverses from forces outside her control, would eventually take their toll.

Her successes and achievements, notable as they were, now seem to have become largely forgotten outside specialist circles. They deserve to be remembered.

Jane’s life was relatively short but, in its own idiosyncratic way, spectacular. She had the rare ability to generate new ideas in totally different fields. She showed considerable tenacity in successfully carrying them through, and an impressive capacity to reinvent herself creatively. But the early deaths of both her parents and her husband, and the two major financial reverses from forces outside her control, would eventually take their toll.

Her successes and achievements, notable as they were, now seem to have become largely forgotten outside specialist circles. They deserve to be remembered.

© Philip McCouat 2017. First published November 2017.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Forgotten Women Artists #2: Jane Loudon: artist, futurist, horticulturist and author”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com.

We welcome your comments on this article. For other articles on mummies, see Mummy Brown; and for science fiction, see The New Time in Literature.

For other articles in this series, see:

Forgotten Women Artists #1: Arcangela Paladini: The Rapid Rise and Fall of a Prodigy

Forgotten Women Artists #3: Marie-Gabrielle Capet: Stepping out from the Shadows

Forgotten Women Artists #4: Michaelina Wautier: entering the limelight after 300 years

Forgotten Women Artists #5: Thérèse Schwartze and the business of painting

Return to Home

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Forgotten Women Artists #2: Jane Loudon: artist, futurist, horticulturist and author”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com.

We welcome your comments on this article. For other articles on mummies, see Mummy Brown; and for science fiction, see The New Time in Literature.

For other articles in this series, see:

Forgotten Women Artists #1: Arcangela Paladini: The Rapid Rise and Fall of a Prodigy

Forgotten Women Artists #3: Marie-Gabrielle Capet: Stepping out from the Shadows

Forgotten Women Artists #4: Michaelina Wautier: entering the limelight after 300 years

Forgotten Women Artists #5: Thérèse Schwartze and the business of painting

Return to Home

End Notes

[1] For a useful summary of Jane’s life, see Koren Whipp, “Jane Loudon” in Project Continua: Women Who Persist (17 June 2013); see also Bea Howe, Lady with Green Fingers: the Life of Jane Loudon, Country Life, 1961; Jack Kramer, Women of Flowers: A Tribute to Victorian Women Illustrators Stewart, Tabori & Chang 1996.

[2] Lisa Hopkins, “Jane C. Loudon’s The Mummy!: Mary Shelley Meets George Orwell, and They Go in a Balloon to Egypt.” Cardiff Corvey: Reading the Romantic Text, Issue 10 (June 2003) at 5-16 http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/romtextv2/files/2013/02/cc10_n01.pdf, accessed October 2017.

[3] Whipp, op cit note 1.

[4] For further discussion of the parallels and differences in each work, see Hopkins, op cit note 2.

[5} Cited in Whipp, op cit note 1.

[6] Bernard V Lightman, Victorian Popularizers of Science: Designing Nature for New Audiences, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2007 at 111; cited by Whipp, op cit note 1.

[7] “Mrs Loudon & the Victorian Garden”, website of Victoria & Albert Museum, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/m/mrs-loudon-victorian-garden/

[8] “Mrs Loudon & the Victorian Garden”, op cit note 7.

[9] Agnes, who herself later wrote books for children.

Return to Home

[2] Lisa Hopkins, “Jane C. Loudon’s The Mummy!: Mary Shelley Meets George Orwell, and They Go in a Balloon to Egypt.” Cardiff Corvey: Reading the Romantic Text, Issue 10 (June 2003) at 5-16 http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/romtextv2/files/2013/02/cc10_n01.pdf, accessed October 2017.

[3] Whipp, op cit note 1.

[4] For further discussion of the parallels and differences in each work, see Hopkins, op cit note 2.

[5} Cited in Whipp, op cit note 1.

[6] Bernard V Lightman, Victorian Popularizers of Science: Designing Nature for New Audiences, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2007 at 111; cited by Whipp, op cit note 1.

[7] “Mrs Loudon & the Victorian Garden”, website of Victoria & Albert Museum, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/m/mrs-loudon-victorian-garden/

[8] “Mrs Loudon & the Victorian Garden”, op cit note 7.

[9] Agnes, who herself later wrote books for children.

Return to Home