Sarka of the South Seas

A story of discovery and re-discovery

Introduction

In a separate article we have already told the remarkable story of the 2010 unveiling of an early graphic novel, written in 1921 by the American watercolourist Charles Nicolas Sarka.

By an extraordinary coincidence, another quite different literary work written by Sarka also surfaced for public view in 2010. This work was a full-length book, entitled Tahiti Nui: Narrative of an Artist in the South Seas (originally Breadfruit and Cocoanuts)[1]. The unpublished 155-page manuscript describes the author’s experiences on an adventurous trip he took to Tahiti and Moorea in 1903.

Sarka’s tatty, dog-eared manuscript, a mixture of typing and handwriting, has had a strange history indeed [2]. It was originally written in New York in the 1920s, but only “rediscovered” in 1966, when Sarka’s 90 year-old widow Grace was tidying up her late husband’s effects. Grace was not wealthy, and had also long dreamed that her husband would finally receive a more fitting appreciation of his artistic achievements than he had received during his lifetime. Hoping to address both of these issues, she gave the manuscript to her niece, with the request to "see what you can do with this?” The niece arranged for “the crumbling sheets of pencilled and penned journal notations” to be assembled in some order, and sent the manuscript to the family’s New York lawyer.

The manuscript eventually found its way to Robert Langdon, an Australian journalist and Tahiti enthusiast. Langdon, as it happened, was an excellent choice – he had recently written a favourable article about Charles Sarka in the Pacific Islands Monthly and was soon to become the head of the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau in Canberra [3]. However, Langdon reluctantly concluded that, despite the manuscript’s inherent interest, and what he described as its old world charm, it was not publishable as it was not sufficiently informative for his purposes. His decision may also have been influenced by the fact that the narrative was unfinished, and that the watercolour paintings that Sarka had originally intended to accompany it had long since disappeared [4].

Nevertheless, he considered that the book could be “of value to historians of the future investigating attitudes of outsiders to Tahiti”, so he arranged for the text to be microfilmed before its return to America. A copy of the microfilm was lodged with the NSW State Library in Sydney [5], with the notation that “no part of this typescript may be reproduced before the year 2010 without the consent of the Estate of Charles Sarka”[6]. It is that text which forms part of the basis of this article.

So, who was this prolific Charles Sarka and what took him to Tahiti in the first place? In this article, we’ll attempt to find some answers.

By an extraordinary coincidence, another quite different literary work written by Sarka also surfaced for public view in 2010. This work was a full-length book, entitled Tahiti Nui: Narrative of an Artist in the South Seas (originally Breadfruit and Cocoanuts)[1]. The unpublished 155-page manuscript describes the author’s experiences on an adventurous trip he took to Tahiti and Moorea in 1903.

Sarka’s tatty, dog-eared manuscript, a mixture of typing and handwriting, has had a strange history indeed [2]. It was originally written in New York in the 1920s, but only “rediscovered” in 1966, when Sarka’s 90 year-old widow Grace was tidying up her late husband’s effects. Grace was not wealthy, and had also long dreamed that her husband would finally receive a more fitting appreciation of his artistic achievements than he had received during his lifetime. Hoping to address both of these issues, she gave the manuscript to her niece, with the request to "see what you can do with this?” The niece arranged for “the crumbling sheets of pencilled and penned journal notations” to be assembled in some order, and sent the manuscript to the family’s New York lawyer.

The manuscript eventually found its way to Robert Langdon, an Australian journalist and Tahiti enthusiast. Langdon, as it happened, was an excellent choice – he had recently written a favourable article about Charles Sarka in the Pacific Islands Monthly and was soon to become the head of the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau in Canberra [3]. However, Langdon reluctantly concluded that, despite the manuscript’s inherent interest, and what he described as its old world charm, it was not publishable as it was not sufficiently informative for his purposes. His decision may also have been influenced by the fact that the narrative was unfinished, and that the watercolour paintings that Sarka had originally intended to accompany it had long since disappeared [4].

Nevertheless, he considered that the book could be “of value to historians of the future investigating attitudes of outsiders to Tahiti”, so he arranged for the text to be microfilmed before its return to America. A copy of the microfilm was lodged with the NSW State Library in Sydney [5], with the notation that “no part of this typescript may be reproduced before the year 2010 without the consent of the Estate of Charles Sarka”[6]. It is that text which forms part of the basis of this article.

So, who was this prolific Charles Sarka and what took him to Tahiti in the first place? In this article, we’ll attempt to find some answers.

Charles Sarka's early life

Charles Nicolas Sarka was born in Chicago in 1879 [7]. His parents were of Czechoslovakian origin, so he could always legitimately claim that he was a true Bohemian. His father was an artistic frame maker, and Charles was encouraged to draw as a child [8], sketching his sisters and copying the pictures that his father framed. By his early teens, he was working for a short-lived comic weekly called The Cricket, for $8 a week [9]. By 16 he was already a staff artist on the Chicago Record, depicting the day’s events – crimes, fires, trials –.in much the same way that press photographers do today. Around this period, he also briefly attended the Art Institute of Chicago.

A little later, still possibly in his teens [10], he moved to New York. He shared an apartment with fellow artists Gus Dirks (the creator of the Katzenjammer Kids comic) and John Tarrant. The apartment was in West Fourteenth Street, which “cut right through the heart of Bohemia”. This area drew most of “the young, the new arrivals and the aspiring”, as rents were cheap. In contrast, the acknowledged leaders of the New York art scene clustered in the “de luxe Quartier Latin in West Tenth Street”, which Sarka describes in Tahiti Nui in a hushed tone of mock awe:

There one settled in a studio when either fame or old age overtook one. That old shrine, known as the Studio Building, harbored old masters like Chase, La Farge, JC Brown, Louis P.A.L Pinxt … We used to talk in whispers when approaching this shrine of art, where the halls shone with the gleam of varnished oak, the lighting Rembrandtian, plus an academic creak in the great stairs, and a silence so profound you could hear the bats’ wings flutter through the labyrinthian halls [11].

Sarka found a job as an illustrator for the New York World and the Herald [12], where he met several artists including George “Pop” Hart [13].

There one settled in a studio when either fame or old age overtook one. That old shrine, known as the Studio Building, harbored old masters like Chase, La Farge, JC Brown, Louis P.A.L Pinxt … We used to talk in whispers when approaching this shrine of art, where the halls shone with the gleam of varnished oak, the lighting Rembrandtian, plus an academic creak in the great stairs, and a silence so profound you could hear the bats’ wings flutter through the labyrinthian halls [11].

Sarka found a job as an illustrator for the New York World and the Herald [12], where he met several artists including George “Pop” Hart [13].

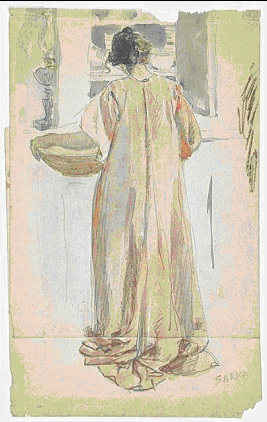

By this time, he had also started painting watercolours in earnest (Fig 1). The good pay he was earning – about $90 week – gave him adequate income to indulge his interest in travel. He realised that he could combine his two interests by going on trips with his artist friends, “blithely seeking the most outlandish corners of the earth for the pure fun of it and using their talents as artists to pay the expenses”[14]. In The Illustrator in America; 1900-1960, Sarka is quoted as saying, “this was my art school: to travel to paint; to paint to travel”[15]. So, in the early years of the century, he camped along the Indian River in Florida, roamed Southern California on horseback, and journeyed to Egypt, typically in conjunction with Pop Hart or other artist friends.

In 1903, however, an entirely new destination beckoned – Tahiti and the South Seas.

The lure of Tahiti

For an artist with such itchy feet, Tahiti must have seemed like a very attractive place. In Tahiti Nui, Sarka attributes his decision to go there to a conversation with Pop Hart in Egypt during one of their sketching trips:

The time was evening. A green veil hung between the moon and the Nile...

Hart: Where shall we go next?

Sarka: Oh, Tahiti I guess. Think we can make it?

Hart: Sure we can. I say… what and where’s Tahiti by the way?

Sarka: It’s a tropical island somewhere in the South Pacific.

Hart: Never mind where it is, Charlie, we’ll find it [16].

With this triumph of optimism over ignorance, Hart accepted Sarka’s suggestion without misgiving. Both men then appear to have forgotten all about it for some months until their return to New York. One morning Hart appeared, waving a steamship ticket.

Hart: Well Charles, I’m off, just got my ticket. Don’t forget to meet me there.

Sarka: Where?

Hart: Why, in Tahiti, as we had planned of course.

But the ticket he had purchased read “Good for one passage to Havana”.

This was not a mistake by Hart. Nor was it was actually a surprise to Sarka that Hart had decided to travel to Tahiti via Cuba. According to Tahiti Nui [17], Hart had a natural instinct for direction, but an aversion to maps and geography. No matter where he was bound, he always went to Cuba first. Being there gave him his bearings. He could always be counted on to reach his destination, even if it may not have been on scheduled time [18].

As it happened, Sarka decided to stay on in New York for a couple of months to make more money for the trip. Hart wrote to him in gentle protest [19]:

Am sorry that I leave … without my old reliable side partner….[I] don’t see why you should want so much money as there is no chance to spend it over there, as we shall get plenty of breadfruit just for the picking, and plenty of fishing.

After Hart arrives in Tahiti, he writes again:

I pity you up North in the snow and cold. No tourists or beggars here… Bring along some spoon hooks and I’ll show you how to catch some fish. Your old pal [20].

Sarka, finally cashed up, eventually set off, full of anticipation for the adventure ahead.

In “leaving the dust of the commonplace behind” to go to Tahiti [21], Sarka was actually following a strong American tradition. In the Western mind, Tahiti represented a place of dreams [22]. Only “discovered” by Europeans in 1767, and proclaimed by Bougainville as a paradise shortly afterwards [23], its remoteness, novelty, physical beauty, leisure and promise of sexual freedom offered relief from a wide variety of dissatisfactions with life at home [24].

For many Americans, in particular, this image had been firmly reinforced by a strong literary tradition, beginning with the writings and letters of American sailors and explorers in the late eighteenth century [25]. The tradition blossomed with the writings of Melville, who provided a counter-image of the America he had left, by portraying happiness as resulting from a freedom from commerce, finance and poverty. With a heady mixture of sex and leisure, and a powerful new concept of the transplanted Western “beachcomber”, Melville’s Typee (1846) and Omoo (1847) exerted far more popular influence in America than the disapproving lecturing of missionary works such as Hiram Bingham’s A Residence of Twenty Years in the Sandwich Islands (1847). Mark Twain soon followed with Roughing It (1872) and Charles Warren Stoddard with South Seas Idylls (1873), in which Tahiti was presented as a cure for urban ills, where the author enjoyed “feasting [his] five senses and finding life a holiday at last”. Stoddard also inspired Robert Louis Stevenson's interest in the South Seas, which culminated in Stevenson and his Californian wife travelling there, resulting in a stream of popular literature based on the Pacific [26].

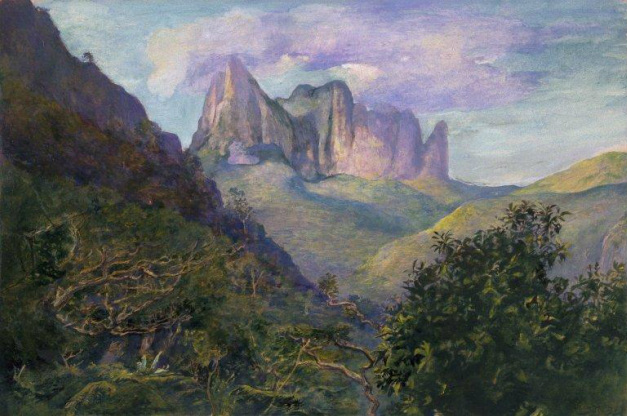

As an artist, Sarka would also have been particularly influenced by the journey of the eminent American historian Henry Adams [27], who went to Tahiti in the 1890s, accompanied by the artist John La Farge [28] (fig 2)), one of the New York “old masters” Sarka mentions in Tahiti Nui. Adams eventually produced the first history of Tahiti [29], while La Farge also wrote an account of his Tahiti adventures and returned to New York with many paintings [29A], further reinforcing Tahiti’s Gauguin-inspired artistic reputation [30]. For Sarka, all these influences were not just theoretical – one of his very first impressions when he sights Papeete is “Shades of Stevenson, Stoddard and Melville!” [31], and he particularly mentions the feeling of excitement he had when approaching the village of Tautira, “the place where Stevenson once lived and La Farge painted” [32].

It is significant also that Sarka was also travelling at the height of the so-called American Renaissance. During this period, which lasted from 1870 to 1920, America witnessed an unprecedented growth in national wealth and political significance, and began to exercise its influence as a major international and commercial power. Its colonial influence in the Pacific region reached its height with the annexation of Hawaii in 1898. Diplomatic and trade expeditions to foreign lands fostered an interest in foreign cultures that was reflected in the art of the period, including an interest in non-western cultures, and fostered a desire for new cultural experiences and exotic subjects [32A}.

The time was evening. A green veil hung between the moon and the Nile...

Hart: Where shall we go next?

Sarka: Oh, Tahiti I guess. Think we can make it?

Hart: Sure we can. I say… what and where’s Tahiti by the way?

Sarka: It’s a tropical island somewhere in the South Pacific.

Hart: Never mind where it is, Charlie, we’ll find it [16].

With this triumph of optimism over ignorance, Hart accepted Sarka’s suggestion without misgiving. Both men then appear to have forgotten all about it for some months until their return to New York. One morning Hart appeared, waving a steamship ticket.

Hart: Well Charles, I’m off, just got my ticket. Don’t forget to meet me there.

Sarka: Where?

Hart: Why, in Tahiti, as we had planned of course.

But the ticket he had purchased read “Good for one passage to Havana”.

This was not a mistake by Hart. Nor was it was actually a surprise to Sarka that Hart had decided to travel to Tahiti via Cuba. According to Tahiti Nui [17], Hart had a natural instinct for direction, but an aversion to maps and geography. No matter where he was bound, he always went to Cuba first. Being there gave him his bearings. He could always be counted on to reach his destination, even if it may not have been on scheduled time [18].

As it happened, Sarka decided to stay on in New York for a couple of months to make more money for the trip. Hart wrote to him in gentle protest [19]:

Am sorry that I leave … without my old reliable side partner….[I] don’t see why you should want so much money as there is no chance to spend it over there, as we shall get plenty of breadfruit just for the picking, and plenty of fishing.

After Hart arrives in Tahiti, he writes again:

I pity you up North in the snow and cold. No tourists or beggars here… Bring along some spoon hooks and I’ll show you how to catch some fish. Your old pal [20].

Sarka, finally cashed up, eventually set off, full of anticipation for the adventure ahead.

In “leaving the dust of the commonplace behind” to go to Tahiti [21], Sarka was actually following a strong American tradition. In the Western mind, Tahiti represented a place of dreams [22]. Only “discovered” by Europeans in 1767, and proclaimed by Bougainville as a paradise shortly afterwards [23], its remoteness, novelty, physical beauty, leisure and promise of sexual freedom offered relief from a wide variety of dissatisfactions with life at home [24].

For many Americans, in particular, this image had been firmly reinforced by a strong literary tradition, beginning with the writings and letters of American sailors and explorers in the late eighteenth century [25]. The tradition blossomed with the writings of Melville, who provided a counter-image of the America he had left, by portraying happiness as resulting from a freedom from commerce, finance and poverty. With a heady mixture of sex and leisure, and a powerful new concept of the transplanted Western “beachcomber”, Melville’s Typee (1846) and Omoo (1847) exerted far more popular influence in America than the disapproving lecturing of missionary works such as Hiram Bingham’s A Residence of Twenty Years in the Sandwich Islands (1847). Mark Twain soon followed with Roughing It (1872) and Charles Warren Stoddard with South Seas Idylls (1873), in which Tahiti was presented as a cure for urban ills, where the author enjoyed “feasting [his] five senses and finding life a holiday at last”. Stoddard also inspired Robert Louis Stevenson's interest in the South Seas, which culminated in Stevenson and his Californian wife travelling there, resulting in a stream of popular literature based on the Pacific [26].

As an artist, Sarka would also have been particularly influenced by the journey of the eminent American historian Henry Adams [27], who went to Tahiti in the 1890s, accompanied by the artist John La Farge [28] (fig 2)), one of the New York “old masters” Sarka mentions in Tahiti Nui. Adams eventually produced the first history of Tahiti [29], while La Farge also wrote an account of his Tahiti adventures and returned to New York with many paintings [29A], further reinforcing Tahiti’s Gauguin-inspired artistic reputation [30]. For Sarka, all these influences were not just theoretical – one of his very first impressions when he sights Papeete is “Shades of Stevenson, Stoddard and Melville!” [31], and he particularly mentions the feeling of excitement he had when approaching the village of Tautira, “the place where Stevenson once lived and La Farge painted” [32].

It is significant also that Sarka was also travelling at the height of the so-called American Renaissance. During this period, which lasted from 1870 to 1920, America witnessed an unprecedented growth in national wealth and political significance, and began to exercise its influence as a major international and commercial power. Its colonial influence in the Pacific region reached its height with the annexation of Hawaii in 1898. Diplomatic and trade expeditions to foreign lands fostered an interest in foreign cultures that was reflected in the art of the period, including an interest in non-western cultures, and fostered a desire for new cultural experiences and exotic subjects [32A}.

Impressions of Tahiti

When Sarka finally arrived in Tahiti, he looked round the Papeete quayside for his friend:

But where was that familiar bearded face? …Around a bend in the beach, I saw a figure in a blue flannel shirt and dungarees, slowly pacing the sand. At my yell, the figure wheeled around and stared. Then suddenly he exploded, “Well, I’ll be damned!.”... We threw our hats high, joined hands, emitted wild and weird whoops, and did a high kick and dance there on the beach…. [33].

In fact, he had hardly recognised Hart, who had not shaved for weeks and whose hair “looked like sparrows had been nesting in it”[34].

Like Hart, Sarka quickly fell under Tahiti’s spell: “How delightfully welcome and friendly it all appeared” he commented [35], and he revelled in this seeming-paradise of blue skies, plentiful food, unspoiled environment and friendly locals [36].

The two friends lodged in an old abandoned bake shop in a little village called Faaa, just outside Papeete, which they converted into a studio. They used this as a base to which they returned periodically during their extensive travels round Tahiti. They explored a large part of the island on foot, hiking as far as the coastal settlement of Tautira, and spent a month on Moorea where they got to be “great friends” with the natives, “especially the youngsters”[37]. During these travels, they usually boarded with different native families, sometimes sleeping in brass beds which the locals used as ornaments, preferring themselves to sleep on the floor. In a later interview, Sarka describes how they would always return to Papeete on “steamer day”, once a month. There they would put up at the home of the American consul, where Sarka says they would sleep “in one of the queerest rooms I had ever slept in”, piled high with newspapers, with both men being wrapped in old American flags [38].

During their travels round the island, they enthusiastically took part in the rituals and festivals and became immersed in the daily activities of Tahitian life [39]. On many evenings, they were entertained by native musicians. The entire village would often gather together with the artists for a communal meal, followed by musical performances. Often Sarka would join in with his accordion, with Pop playing the bones in a typically unrestrained manner.

Their local hosts typically refused to accept money from the artists for their food and lodgings. Sarka found that even leaving money was a grave breach of ethics [40], but honour was often satisfied on both sides by the offer of a portrait sketch as payment.

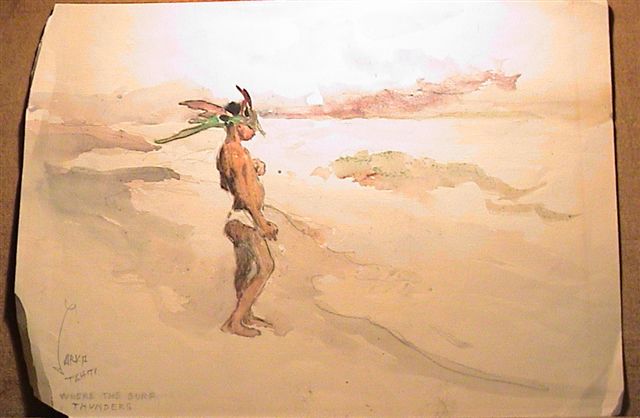

It was a vagabond existence, equivalent to many backpacker/buskers of modern days. Both artists typically spent many hours a day sketching. “Every view was beautiful enough to sketch, every native was picturesque enough to draw. We were busy all the time”, Sarka reported [41]. Their preference was to paint images of people whenever possible and, when it was not, they painted landscapes (Fig 3).

But where was that familiar bearded face? …Around a bend in the beach, I saw a figure in a blue flannel shirt and dungarees, slowly pacing the sand. At my yell, the figure wheeled around and stared. Then suddenly he exploded, “Well, I’ll be damned!.”... We threw our hats high, joined hands, emitted wild and weird whoops, and did a high kick and dance there on the beach…. [33].

In fact, he had hardly recognised Hart, who had not shaved for weeks and whose hair “looked like sparrows had been nesting in it”[34].

Like Hart, Sarka quickly fell under Tahiti’s spell: “How delightfully welcome and friendly it all appeared” he commented [35], and he revelled in this seeming-paradise of blue skies, plentiful food, unspoiled environment and friendly locals [36].

The two friends lodged in an old abandoned bake shop in a little village called Faaa, just outside Papeete, which they converted into a studio. They used this as a base to which they returned periodically during their extensive travels round Tahiti. They explored a large part of the island on foot, hiking as far as the coastal settlement of Tautira, and spent a month on Moorea where they got to be “great friends” with the natives, “especially the youngsters”[37]. During these travels, they usually boarded with different native families, sometimes sleeping in brass beds which the locals used as ornaments, preferring themselves to sleep on the floor. In a later interview, Sarka describes how they would always return to Papeete on “steamer day”, once a month. There they would put up at the home of the American consul, where Sarka says they would sleep “in one of the queerest rooms I had ever slept in”, piled high with newspapers, with both men being wrapped in old American flags [38].

During their travels round the island, they enthusiastically took part in the rituals and festivals and became immersed in the daily activities of Tahitian life [39]. On many evenings, they were entertained by native musicians. The entire village would often gather together with the artists for a communal meal, followed by musical performances. Often Sarka would join in with his accordion, with Pop playing the bones in a typically unrestrained manner.

Their local hosts typically refused to accept money from the artists for their food and lodgings. Sarka found that even leaving money was a grave breach of ethics [40], but honour was often satisfied on both sides by the offer of a portrait sketch as payment.

It was a vagabond existence, equivalent to many backpacker/buskers of modern days. Both artists typically spent many hours a day sketching. “Every view was beautiful enough to sketch, every native was picturesque enough to draw. We were busy all the time”, Sarka reported [41]. Their preference was to paint images of people whenever possible and, when it was not, they painted landscapes (Fig 3).

In Tahiti Nui, he describes the locals’ attitude to posing:

Loath as the boys and girls were to leave their fun of dancing to pose, they bowed to the inevitable good naturedly, and posed till they tired or wobbled out of position, when [Pop] would bring them suddenly back with a shout. Posing for hours was wearisome work for these flower crowned amiable big children of a less self-conscious world, lounging happy and content under a pandanus roof, sipping their amber mountain orangeade and singing those familiar island fandangos [42].

Loath as the boys and girls were to leave their fun of dancing to pose, they bowed to the inevitable good naturedly, and posed till they tired or wobbled out of position, when [Pop] would bring them suddenly back with a shout. Posing for hours was wearisome work for these flower crowned amiable big children of a less self-conscious world, lounging happy and content under a pandanus roof, sipping their amber mountain orangeade and singing those familiar island fandangos [42].

Based on his personal experiences over some months, Sarka was tremendously impressed by many of the Tahitians’ attributes:

The Tahitian knows nothing of hooliganism or rough-housing. He possesses a natural gentility which seldom oversteps the bounds of good breeding [43] ….with a natural modesty, which is one of their national characteristics [44] …Good sportsmanship was the predominant point in all their games [45] ….They neither preach nor sermonise on elaborate doctrines, but practice a high order of man-to-man fair dealing, regarding all actions from the standpoint of good sportsmanship and justice [46].

These people know the art of conversation. Under all their light conversation runs a thread of sincerity. They use no “weasel” words when speaking from conviction. Neither profuse, nor apologetic in their manner, they look you straight in the eye in a frank, friendly and fearless manner, and are careful not to obtrude where they are not welcome [47].

The children were delightful, as usual [48] …[They] were allowed to do pretty much as they pleased, yet seldom, if ever, did I see one who needed chastisement. I chummed with them frequently [49].

Every lad seemed to possess a wide and varied knowledge of the different plants and their uses for practical purposes, including food and decoration. Recognising the gender of trees and plants, they were often amused at my ignorance. .. [T]heir self reliance manifested itself in an emergency with the raw products at their disposal. A basket? – woven from palmetto leaf in a jiffy. Emergency rope? – a long peel of green smooth bark stripped from a sapling. String? – the strand from a banana leaf rib served well [50].

Both Sarka and Hart shared the Tahitians’ love of music:

When there is moonlight there is always music somewhere in Tahiti. It is wondrous music, stealing through the palms on the soft night breezes. When the himinis (traditional native songs) started, we put away our instruments to listen to the deep, melodious island orchestra which, much like the surf on the reef voicing the sound of the sea in its thunderous roar all day, expressed the deeper feelings of the Tahitians as a nation [51] …As guests of honour we were privileged to sit with the singers …. From the floor, two flaming lamps lighted up the long chamber, casting against the ceiling thatch great flickering shadows of the seated figures [52] (Fig 5).

The Tahitian knows nothing of hooliganism or rough-housing. He possesses a natural gentility which seldom oversteps the bounds of good breeding [43] ….with a natural modesty, which is one of their national characteristics [44] …Good sportsmanship was the predominant point in all their games [45] ….They neither preach nor sermonise on elaborate doctrines, but practice a high order of man-to-man fair dealing, regarding all actions from the standpoint of good sportsmanship and justice [46].

These people know the art of conversation. Under all their light conversation runs a thread of sincerity. They use no “weasel” words when speaking from conviction. Neither profuse, nor apologetic in their manner, they look you straight in the eye in a frank, friendly and fearless manner, and are careful not to obtrude where they are not welcome [47].

The children were delightful, as usual [48] …[They] were allowed to do pretty much as they pleased, yet seldom, if ever, did I see one who needed chastisement. I chummed with them frequently [49].

Every lad seemed to possess a wide and varied knowledge of the different plants and their uses for practical purposes, including food and decoration. Recognising the gender of trees and plants, they were often amused at my ignorance. .. [T]heir self reliance manifested itself in an emergency with the raw products at their disposal. A basket? – woven from palmetto leaf in a jiffy. Emergency rope? – a long peel of green smooth bark stripped from a sapling. String? – the strand from a banana leaf rib served well [50].

Both Sarka and Hart shared the Tahitians’ love of music:

When there is moonlight there is always music somewhere in Tahiti. It is wondrous music, stealing through the palms on the soft night breezes. When the himinis (traditional native songs) started, we put away our instruments to listen to the deep, melodious island orchestra which, much like the surf on the reef voicing the sound of the sea in its thunderous roar all day, expressed the deeper feelings of the Tahitians as a nation [51] …As guests of honour we were privileged to sit with the singers …. From the floor, two flaming lamps lighted up the long chamber, casting against the ceiling thatch great flickering shadows of the seated figures [52] (Fig 5).

While admiring the “spontaneity and enthusiasm” that usually accompanied any work the Tahitians set out to do [53], Sarka predicts that their measured attitude to work would not serve them well in the face of advancing westernisation:

The Tahitian finds his small patch of tarrow [taro], with what nature provides in the way of fish, breadfruit and other nourishing and delectable native vegetation, quite sufficient for his needs. He does not believe in being a slave to the soil. He is always willing to lend a hand to a friend or neighbour in need, but to lean on a hoe, or on a mortgage, is beneath his dignity. Thus, being free of the economic problem with its attendant evils of poverty, unemployment, crime and hunger, his fate is sealed when competition appears, and he is unable to copy with it or to understand its ruthless nature [54].

He also shares the predictable Westerners’ view of the people as simple and uncomplicated:

How like the native islander were these elemental changes. He was a child of nature, as moody as the fleeting clouds that hide the sun, and frowning like those dark beetling crags. Just as [the clouds] are shot through with a shaft of sunlight, so his sudden smile appears like the sunburst [55].

Similarly, he comments on how some of the by-products of western culture produce wondering reactions:

Some back numbers of magazines were of absorbing interest to the women, particularly the advertising pages. One advertisement for a corset brought forth this remark: “How can a wahine [woman] eat, wearing something like that!” Illustrations of guns and knives were passed by with a shrug of horror. Covers picturing pretty girls left them in a sort of daze – a wistful wonderment of “Where but in regions beyond can such creatures exist?”[56]

Interestingly, Sarka says little about the physical appearance of the young women who contributed so much to Tahiti’s reputation in the West as a prototypical “island of love”. It appears by this stage that Western views of Tahitian beauty may have changed. So, instead of Bougainville’s eighteenth century vision of a young nymph with the celestial body of Venus, Henry Adams in the 1890s was commenting sourly that “the Polynesian woman seems to me too much like the Polynesian man; the difference is not great enough to admit of sentiment, only of physical divergence” [57]. Sarka’s only reference to the women’s appearance appears quite late in Tahiti Nui, where he simply remarks, a little ambiguously, that one young woman is “refreshingly” pretty [58].

Overall, Sarka’s impressions have elements of the concept of the “romantic savage”. As described by Bernard Smith [59], this portrays the “typical” native person as being close to nature, courageous, with emotional depth, and child-like warmth. This is, relatively speaking, more realistic than the classicised version of the noble savage, and retains little vestige of the 19th century missionary-inspired image of the violently pagan “ignoble savage” [60]. On the other hand, the warm attachments that Sarka forms, his eagerness to join in local activities and his generally non-judgmental attitude – at least by the standards of his time – make it difficult to pigeonhole his views one way or the other.

The Tahitian finds his small patch of tarrow [taro], with what nature provides in the way of fish, breadfruit and other nourishing and delectable native vegetation, quite sufficient for his needs. He does not believe in being a slave to the soil. He is always willing to lend a hand to a friend or neighbour in need, but to lean on a hoe, or on a mortgage, is beneath his dignity. Thus, being free of the economic problem with its attendant evils of poverty, unemployment, crime and hunger, his fate is sealed when competition appears, and he is unable to copy with it or to understand its ruthless nature [54].

He also shares the predictable Westerners’ view of the people as simple and uncomplicated:

How like the native islander were these elemental changes. He was a child of nature, as moody as the fleeting clouds that hide the sun, and frowning like those dark beetling crags. Just as [the clouds] are shot through with a shaft of sunlight, so his sudden smile appears like the sunburst [55].

Similarly, he comments on how some of the by-products of western culture produce wondering reactions:

Some back numbers of magazines were of absorbing interest to the women, particularly the advertising pages. One advertisement for a corset brought forth this remark: “How can a wahine [woman] eat, wearing something like that!” Illustrations of guns and knives were passed by with a shrug of horror. Covers picturing pretty girls left them in a sort of daze – a wistful wonderment of “Where but in regions beyond can such creatures exist?”[56]

Interestingly, Sarka says little about the physical appearance of the young women who contributed so much to Tahiti’s reputation in the West as a prototypical “island of love”. It appears by this stage that Western views of Tahitian beauty may have changed. So, instead of Bougainville’s eighteenth century vision of a young nymph with the celestial body of Venus, Henry Adams in the 1890s was commenting sourly that “the Polynesian woman seems to me too much like the Polynesian man; the difference is not great enough to admit of sentiment, only of physical divergence” [57]. Sarka’s only reference to the women’s appearance appears quite late in Tahiti Nui, where he simply remarks, a little ambiguously, that one young woman is “refreshingly” pretty [58].

Overall, Sarka’s impressions have elements of the concept of the “romantic savage”. As described by Bernard Smith [59], this portrays the “typical” native person as being close to nature, courageous, with emotional depth, and child-like warmth. This is, relatively speaking, more realistic than the classicised version of the noble savage, and retains little vestige of the 19th century missionary-inspired image of the violently pagan “ignoble savage” [60]. On the other hand, the warm attachments that Sarka forms, his eagerness to join in local activities and his generally non-judgmental attitude – at least by the standards of his time – make it difficult to pigeonhole his views one way or the other.

An established artist

On Sarka’s return from Tahiti, a 1904 exhibition of his works was promisingly successful, and for the first time he started to become known as “Sarka of the South Seas”[61]. He continued to profitably combine work and travel – the Philippines, Hawaii, Paris, Costa Rica – and his reputation began growing. By 1906 the New York Times referred to him as “that world wanderer Charles Sarka …getting lots of the vivid sunlight he loves to paint, and no end of insight into the ways of the natives”[62]. Although he did not realise it at the time, Sarka was entering a golden period.

As an artist, Sarka was not interested in majestic mountain scenes or large scale views. Reflecting his background in illustration, he favoured immediacy, intimacy, truth and freshness. This did not necessarily coincide with the traditional approach. As he says in Tahiti Nui:

Pure painting was not considered painting unless done with meticulousness. [This meant that] after one had painted his subject on canvas spontaneously, joyously and perhaps a little sloppily, which, by and large seemed to reflect a freshness resembling life, it was regarded as merely a sketch and unfinished. The object, according to the prevalent schools of art thought, was to carry the technique farther and farther to such a point of finish that would make it difficult to tell whether the finished product had been painted with a camel hair brush or an atomiser. A joyous picture was taboo in the Holy of Holies [63].

An early New York Times review of an exhibition of Sarka’s Egyptian and Californian sketches had summed up the position well:

Mr Sarka has far to go before he can handle watercolours like a master, but meantime he has the qualities of youth in quick perceptions and boldness of hand, so that his hasty bedevilment of paper gives one the impression of the scenes like an instantaneous view, offers clever arrangements in masses and blotches of colour, and sometimes expresses very admirably movement …. The realism of the reporter divests the Oriental of his or her glamour and tells us harshly how ugly and squalid he or she may appear. Where the artist hitherto has sought for fine types of the Fellahin and Arab, this young modern takes delight in showing the peasant mother with gross, protruding lips and ungainly figure [64].

Even twenty years later, as noted in a New York Times review of an exhibition of Sarka’s Puerto Rico paintings, the same values remain:

The paintings are entirely devoid of the sensational brilliancy for which artists confronted by tropical scenes continually strive and the impression conveyed is that of unusual fidelity to actual appearances. Caves, cocoanut palms, reefs and coral shores, manzanilla trees and the men, women and goats of the islands, provide enough picturesqueness with out any necessity for exaggeration. The artist is skilful in the use of his medium and in his presentation of his subject shows a sense of humour too subtle to slip into the grotesque, but effective in adding vitality to the result [65].

On the other hand, Sarka evidently was not overly impressed with some of the more self-conscious avant garde artistic experiments that proliferated in the early years of the century. When Pop Hart exhibited at the influential Armory Show of 1913, Sarka wondered if the organiser had simply unearthed Pop’s traditional Pan and Nymphs, “had it cut apart and copies made, then put the pieces together again, helter-skelter, and sat back to watch the fur fly” [66]. Similarly, describing a 1917 exhibition of the Independent Artists’ Association, he comments, “I was there the other day, two or three other people were there wandering round making loud echoes with their feet. The advanced arts have an atmosphere of staleness, mingled with a feeling of ‘where have I seen that before’ and loneliness – it is becoming a bore”[67].

Deeper questions about the role of art also surface in Tahiti Nui [68]. In what appears to be a dream sequence (one of the few occasions where Sarka departs from the literal), Sarka and Pop are arguing with a mysterious, rather ominous, native philosopher (“Marq”, presumably short for Marquesan) [69] about the role of art:

Marq: Art is truth; it never lies. Of course that doesn’t mean that the truth it tells is always pretty or sweet, but that’s what it must tell. No matter how much the artist lies about it, he’s got to tell the truth…

Sarka: Don’t you believe there’s such a thing as inspiration in art?

Marq: No. It’s perspiration – just plain honest sweat.

Sarka: What about soul? You’ll admit that’s important.

Marq: Nothing of the kind. The soul is just a little red thing. But art is more abstract, primitive, fundamental [70].

An interesting insight into Sarka’s passionate interest in his art – and, incidentally, of the amount of work he was doing – is provided by a dramatic fire that destroyed his Gramercy Park home/studio in 1914. As racily reported in the New York Times [71], onlookers attracted by clouds of black and purple smoke saw “an excited artist … wearing a brown studio coat and an artist’s cap”, throwing his easel and a half-finished oil painting from his second floor window into the street below. Sarka himself then came rushing out, holding his dog and leading his wife by the hand, all of them choking with smoke. The onlookers, “being folk of artistic temperament”, simply milled around ineffectually, so Sarka was forced to take over…

As he sprinted toward the fire alarm box, his artist’s necktie streaming out behind, he bumped squarely into a policeman holding a man by the arm. “Shoot [unlock] the alarm box!” called out Sarka… “My studio’s burning up”.

“But I’ve got a prisoner”, protested the policeman. “What can I do? He’s a burglar at that.”

“Oh, hang the prisoner,” puffed the artist. “Don’t you realise my paintings are burning up – a whole hundred of them? Think of it! And 200 watercolors!”

The policeman did realise it. The appeal of the artist was hypnotic. Almost in an instant the alarm box was open…”

The burglar naturally takes the opportunity to escape, and disappears, chased by the policeman. However the fire fighters’ subsequent efforts to quell the rampaging fire ran into difficulties. Sarka stands it all for a time, but he finally protests that he simply has to go in and rescue some manuscripts. Finally he convinces the authorities to set up a ladder against the front window:

Deputy Chief Skelly … went in to see that it was passably safe, and then he motioned to the artist to follow him. A moment later the artist came out again with a water-soaked manuscript in a big brown envelope and a smile that brought cheers from all his fellow-artists...

As an artist, Sarka was not interested in majestic mountain scenes or large scale views. Reflecting his background in illustration, he favoured immediacy, intimacy, truth and freshness. This did not necessarily coincide with the traditional approach. As he says in Tahiti Nui:

Pure painting was not considered painting unless done with meticulousness. [This meant that] after one had painted his subject on canvas spontaneously, joyously and perhaps a little sloppily, which, by and large seemed to reflect a freshness resembling life, it was regarded as merely a sketch and unfinished. The object, according to the prevalent schools of art thought, was to carry the technique farther and farther to such a point of finish that would make it difficult to tell whether the finished product had been painted with a camel hair brush or an atomiser. A joyous picture was taboo in the Holy of Holies [63].

An early New York Times review of an exhibition of Sarka’s Egyptian and Californian sketches had summed up the position well:

Mr Sarka has far to go before he can handle watercolours like a master, but meantime he has the qualities of youth in quick perceptions and boldness of hand, so that his hasty bedevilment of paper gives one the impression of the scenes like an instantaneous view, offers clever arrangements in masses and blotches of colour, and sometimes expresses very admirably movement …. The realism of the reporter divests the Oriental of his or her glamour and tells us harshly how ugly and squalid he or she may appear. Where the artist hitherto has sought for fine types of the Fellahin and Arab, this young modern takes delight in showing the peasant mother with gross, protruding lips and ungainly figure [64].

Even twenty years later, as noted in a New York Times review of an exhibition of Sarka’s Puerto Rico paintings, the same values remain:

The paintings are entirely devoid of the sensational brilliancy for which artists confronted by tropical scenes continually strive and the impression conveyed is that of unusual fidelity to actual appearances. Caves, cocoanut palms, reefs and coral shores, manzanilla trees and the men, women and goats of the islands, provide enough picturesqueness with out any necessity for exaggeration. The artist is skilful in the use of his medium and in his presentation of his subject shows a sense of humour too subtle to slip into the grotesque, but effective in adding vitality to the result [65].

On the other hand, Sarka evidently was not overly impressed with some of the more self-conscious avant garde artistic experiments that proliferated in the early years of the century. When Pop Hart exhibited at the influential Armory Show of 1913, Sarka wondered if the organiser had simply unearthed Pop’s traditional Pan and Nymphs, “had it cut apart and copies made, then put the pieces together again, helter-skelter, and sat back to watch the fur fly” [66]. Similarly, describing a 1917 exhibition of the Independent Artists’ Association, he comments, “I was there the other day, two or three other people were there wandering round making loud echoes with their feet. The advanced arts have an atmosphere of staleness, mingled with a feeling of ‘where have I seen that before’ and loneliness – it is becoming a bore”[67].

Deeper questions about the role of art also surface in Tahiti Nui [68]. In what appears to be a dream sequence (one of the few occasions where Sarka departs from the literal), Sarka and Pop are arguing with a mysterious, rather ominous, native philosopher (“Marq”, presumably short for Marquesan) [69] about the role of art:

Marq: Art is truth; it never lies. Of course that doesn’t mean that the truth it tells is always pretty or sweet, but that’s what it must tell. No matter how much the artist lies about it, he’s got to tell the truth…

Sarka: Don’t you believe there’s such a thing as inspiration in art?

Marq: No. It’s perspiration – just plain honest sweat.

Sarka: What about soul? You’ll admit that’s important.

Marq: Nothing of the kind. The soul is just a little red thing. But art is more abstract, primitive, fundamental [70].

An interesting insight into Sarka’s passionate interest in his art – and, incidentally, of the amount of work he was doing – is provided by a dramatic fire that destroyed his Gramercy Park home/studio in 1914. As racily reported in the New York Times [71], onlookers attracted by clouds of black and purple smoke saw “an excited artist … wearing a brown studio coat and an artist’s cap”, throwing his easel and a half-finished oil painting from his second floor window into the street below. Sarka himself then came rushing out, holding his dog and leading his wife by the hand, all of them choking with smoke. The onlookers, “being folk of artistic temperament”, simply milled around ineffectually, so Sarka was forced to take over…

As he sprinted toward the fire alarm box, his artist’s necktie streaming out behind, he bumped squarely into a policeman holding a man by the arm. “Shoot [unlock] the alarm box!” called out Sarka… “My studio’s burning up”.

“But I’ve got a prisoner”, protested the policeman. “What can I do? He’s a burglar at that.”

“Oh, hang the prisoner,” puffed the artist. “Don’t you realise my paintings are burning up – a whole hundred of them? Think of it! And 200 watercolors!”

The policeman did realise it. The appeal of the artist was hypnotic. Almost in an instant the alarm box was open…”

The burglar naturally takes the opportunity to escape, and disappears, chased by the policeman. However the fire fighters’ subsequent efforts to quell the rampaging fire ran into difficulties. Sarka stands it all for a time, but he finally protests that he simply has to go in and rescue some manuscripts. Finally he convinces the authorities to set up a ladder against the front window:

Deputy Chief Skelly … went in to see that it was passably safe, and then he motioned to the artist to follow him. A moment later the artist came out again with a water-soaked manuscript in a big brown envelope and a smile that brought cheers from all his fellow-artists...

Graphic works

In parallel with his watercolour career, and far overshadowing it in commercial terms, Sarka managed to obtain a reasonable amount of work illustrating books, posters and an extraordinary range of popular magazines – Harper’s, Scribner’s, Collier’s, Cosmopolitan, Everybody’s, Blue Book, Outing, Red Book, Judge, Success, Metropolitan and American magazines [72]. His friend, nature artist Paul Bransom, declared that throughout his long life in art, “Sarka never drew a bad line.” Commentator James Crawford suggests that Sarka’s ability to capture people and make them alive with bold quick strokes was establishing him as one of the best illustrators of the time [73].

Sarka’s graphic art also flowed over into his letters, which he commonly adorned with elaborate, humorous sketches. Typical examples, from a letter to Bransom, are reproduced in the Smithsonian’s The Art of the Illustrated Letter. These sketches are not just decorative. While captioning them “The Joys of City Life” and “The Joy of Country Life”, Sarka adds the by-line “everything has its drawbacks”, wryly comparing the small town sameness of Main St Wyoming, where Bransom was teaching, to the big city perversions of Central Park, near Sarka’s New York apartment [74].

Perhaps, however, Sarka’s major achievement in illustration – also only recently unveiled – is his graphic novel Song Without Music [75]. The full story of that unusual document, and an assessment of its possible significance, is the subject of our separate article “Discovery of an Early Graphic Novel”.

Sarka’s graphic art also flowed over into his letters, which he commonly adorned with elaborate, humorous sketches. Typical examples, from a letter to Bransom, are reproduced in the Smithsonian’s The Art of the Illustrated Letter. These sketches are not just decorative. While captioning them “The Joys of City Life” and “The Joy of Country Life”, Sarka adds the by-line “everything has its drawbacks”, wryly comparing the small town sameness of Main St Wyoming, where Bransom was teaching, to the big city perversions of Central Park, near Sarka’s New York apartment [74].

Perhaps, however, Sarka’s major achievement in illustration – also only recently unveiled – is his graphic novel Song Without Music [75]. The full story of that unusual document, and an assessment of its possible significance, is the subject of our separate article “Discovery of an Early Graphic Novel”.

ART AND FAME, OR THE LACK OF IT

Back in 1907, Sarka had started visiting Canada Lake, an idyllic spot in Northern New York’s Adirondack Mountains [76]. This was the centre for a colony of artists and writers from Greenwich Village who vacationed or settled there [77]. The first had been cartoonist and illustrator Clare Victor Dwiggins (78). At the Dwiggins’ place (called the “Dwigwam”), Sarka met Grace Jones, one of three sisters, “all of whom were the toast of the art world” [79]. Sarka and Grace were married in 1909 or 1910, and in 1912 they set up a fairly basic summer residence at the Lake.

Over the next decade or so, Sarka’s watercolours and illustrations continued to earn him a reasonable living and a steadily growing reputation. By the 1920s, James Crawford concludes that although never actually achieving public fame, Sarka was being accepted by critics as one of the better American watercolourists of his generation [80]. His watercolour skills had reached a high level. His works from the Canada Lake period exhibit a greater complexity, while still retaining their intimacy, and Sarka is effectively creating freshness by better exploiting the unpainted white spaces of the paper surface.

Over the next decade or so, Sarka’s watercolours and illustrations continued to earn him a reasonable living and a steadily growing reputation. By the 1920s, James Crawford concludes that although never actually achieving public fame, Sarka was being accepted by critics as one of the better American watercolourists of his generation [80]. His watercolour skills had reached a high level. His works from the Canada Lake period exhibit a greater complexity, while still retaining their intimacy, and Sarka is effectively creating freshness by better exploiting the unpainted white spaces of the paper surface.

However, from this point, Sarka’s public career starts on a steady decline. There were a number of reasons for this. Sarka’s artistic realism had started to go out of favour and his watercolours began to be regarded as old-fashioned. His magazine and newspaper illustration commissions also started drying up, as photography increasingly took over the traditional illustrator’s role [80A]. The financial pressures of keeping an apartment in New York and the Canada Lake summer house, basic as it was, also started to have an effect. Sarka’s friend Paul Bransom even blamed Grace for “ruining” Sarka’s career with her unrealistic (and unfulfilled) dreams of building a sixteen room mansion at Canada Lake, thus restricting him from the travel that had nurtured his creativity [81]. Crawford notes that had Sarka continued to travel and aggressively exhibit works based on those trips during his lifetime, his career may have prospered longer. On the other hand, however, “many of his most subtle and best works would not have been painted” [82].

By the Depression years, opportunities for work had all but evaporated [83], apart from some mural commissions under the New Deal public works program. Sarka continued to paint – “every day he was at Canada Lake he made a watercolour sketch”, according to his niece [84] – but he sold little, and gave many away or sold them to friends. Later, he supported himself by selling paintings of people’s homes and noteworthy historic structures, and street paintings in a naïve manner under the name “Nicholas”. Sarka continued to paint until he was well into his seventies [85]. Apparently, when he died in 1960, only a few of his closest friends had any idea that he had ever been to the South Seas [86].

After his death, many of his paintings were discovered stored in a Staten Island warehouse [87], and in 1963 there was a successful retrospective exhibition of his works. In the decades since, however, Sarka’s reputation has resumed its slow decline, enlivened by occasional sales – most notably, from the estate of the late Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis – and small exhibitions in New York galleries, most recently in 1999 [88]. Currently, a number of Sarka’s works are still held by major institutions – the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Brooklyn Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. However, it appears that none of these are on public view [89].

What then do we make of Sarka’s artistic career? It seems that almost everyone who has ever written about Sarka feels the need to apologise for his obscurity. Langdon, writing in the 1960s says, “Even if you pride yourself on your knowledge of South Seas history or art, you can fairly be excused if you have never heard of the artist Charles Sarka” [90]. Thirty years later, Crawford was still explaining, “Even the most avid students of American watercolour painting may not be aware of the work of Charles Sarka”[91].

This contrast between early promise and later obscurity forms a constant theme in Sarka’s own writings from a very early stage. In his 1903 journal, Sarka has the Western artist asking of the native, “What then was the value of these paintings?” In reply, the Tahitian says, “When you are dead and gone, they’d bring them out and sell them for a whacking good price and you would then be famous, but dead and gone”[92]. An almost identical conversation takes place in Tahiti Nui, twenty years later [93].

Although Sarka eventually and reluctantly resigned himself to the fact that fame would elude him, Grace had always remained quite hopeful, and was disappointed that Charles never made the big time [94]. As the couple’s financial fortunes waned – though they always remained “comfortable”, if not affluent – Grace reportedly became somewhat overly concerned with money. In her dreams of wealth, she repeatedly told friends that she knew the whereabouts of “buried treasure” that would make their fortunes. Apparently, she came to believe that a map she had been given showed the location, either somewhere in Cuba, or underground on their Canada Lake property [95].

Maybe she felt that she had finally found a form of buried treasure when she came across the manuscript of Tahiti Nui after Charles’ death. However, as we have seen, attempts to get that book published came to nothing. Grace eventually died in her mid-nineties, having to be satisfied with the knowledge that the text of the book had at least been preserved for posterity. Sadly, she would never know that the subsequent unveiling of Song Without Music would enable her husband’s achievements to be considered anew.□

© Philip McCouat, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2022 (excluding extracts from Tahiti Nui)

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Sarka of the South Seas", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

By the Depression years, opportunities for work had all but evaporated [83], apart from some mural commissions under the New Deal public works program. Sarka continued to paint – “every day he was at Canada Lake he made a watercolour sketch”, according to his niece [84] – but he sold little, and gave many away or sold them to friends. Later, he supported himself by selling paintings of people’s homes and noteworthy historic structures, and street paintings in a naïve manner under the name “Nicholas”. Sarka continued to paint until he was well into his seventies [85]. Apparently, when he died in 1960, only a few of his closest friends had any idea that he had ever been to the South Seas [86].

After his death, many of his paintings were discovered stored in a Staten Island warehouse [87], and in 1963 there was a successful retrospective exhibition of his works. In the decades since, however, Sarka’s reputation has resumed its slow decline, enlivened by occasional sales – most notably, from the estate of the late Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis – and small exhibitions in New York galleries, most recently in 1999 [88]. Currently, a number of Sarka’s works are still held by major institutions – the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Brooklyn Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. However, it appears that none of these are on public view [89].

What then do we make of Sarka’s artistic career? It seems that almost everyone who has ever written about Sarka feels the need to apologise for his obscurity. Langdon, writing in the 1960s says, “Even if you pride yourself on your knowledge of South Seas history or art, you can fairly be excused if you have never heard of the artist Charles Sarka” [90]. Thirty years later, Crawford was still explaining, “Even the most avid students of American watercolour painting may not be aware of the work of Charles Sarka”[91].

This contrast between early promise and later obscurity forms a constant theme in Sarka’s own writings from a very early stage. In his 1903 journal, Sarka has the Western artist asking of the native, “What then was the value of these paintings?” In reply, the Tahitian says, “When you are dead and gone, they’d bring them out and sell them for a whacking good price and you would then be famous, but dead and gone”[92]. An almost identical conversation takes place in Tahiti Nui, twenty years later [93].

Although Sarka eventually and reluctantly resigned himself to the fact that fame would elude him, Grace had always remained quite hopeful, and was disappointed that Charles never made the big time [94]. As the couple’s financial fortunes waned – though they always remained “comfortable”, if not affluent – Grace reportedly became somewhat overly concerned with money. In her dreams of wealth, she repeatedly told friends that she knew the whereabouts of “buried treasure” that would make their fortunes. Apparently, she came to believe that a map she had been given showed the location, either somewhere in Cuba, or underground on their Canada Lake property [95].

Maybe she felt that she had finally found a form of buried treasure when she came across the manuscript of Tahiti Nui after Charles’ death. However, as we have seen, attempts to get that book published came to nothing. Grace eventually died in her mid-nineties, having to be satisfied with the knowledge that the text of the book had at least been preserved for posterity. Sadly, she would never know that the subsequent unveiling of Song Without Music would enable her husband’s achievements to be considered anew.□

© Philip McCouat, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2022 (excluding extracts from Tahiti Nui)

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Sarka of the South Seas", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the invaluable assistance of the following people in the preparation of this article: Ewen Maidment and Joanna Sassoon of the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, Canberra; Michelle Lea Tift-Davis of Davis & Langdale Art Gallery, New York City; Marion Zapata of Adirondack Life magazine; Ann Chennault, American Watercolour Society, New York City; Robyn Gulstrom of Kalamazoo, Michigan; and Ruth Greene-McNally of the Arkell Art Gallery and Museum at Canajoharie, New York

The author would welcome any additional images of Sarka’s works, particularly those of the Canada Lake period, which would be able to be reproduced in future updates of this article.

The author would welcome any additional images of Sarka’s works, particularly those of the Canada Lake period, which would be able to be reproduced in future updates of this article.

End Notes

1. “Tahiti Nui” literally means “Big Tahiti”. The island of Tahiti consists of two roundish volcanic land masses linked by an isthmus. Tahiti Nui refers to the bigger, more northerly one.

2. This account is based on correspondence over the period 1967-1969 received by Robert Langdon, the Executive Officer of the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, Canberra. Copies of this correspondence were kindly made available by the Bureau.

3. The article was “America’s Art Lovers Discover ‘Sarka of the South Seas’”, Pacific Islands Monthly, Dec 1966, 93. Langdon had also written a history, Tahiti - Island of Love, first published in 1959. A good part of his early work with the Bureau focused on Tahitian documents. He died in 2003.

4. Crawford has suggested that the reason that the book was not originally published back in the 1920s or 1930s was that it was entirely in the form of a Socratic dialogue (Crawford, J, “The Watercolour Tradition of Charles Sarka”, American Art Review, Vol XI No 6 (Dec 1999), 140 at 144). However there is only one short section in Tahiti Nui that could be described in this way.

5. There is another copy in the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian.

6. The year 2010 represented the 50th anniversary of Sarka’s death in 1960.

7. His middle name is sometimes misspelled as “Nicholas”.

8. McMartin, B, “Sure Strokes on a Bright Canvas”, Adirondack Life, Vol XXVI, No 5 (July /August 1995) at 34.

9. Langdon, R, “America’s Art Lovers Discover ‘Sarka of the South Seas’”, Pacific Islands Monthly, Dec 1966, 93 at 95

10. Or, alternatively, at age 22 according to Gilbert, G, George Overbury “Pop” Hart: His Life and Art, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 1986, at 13.

11. Sarka, op cit, Introduction p 1, 2. For the sake of clarity, some minor subediting changes have been made to some of the quotations from Tahiti Nui in this article.

12. Crawford, op cit at 140.

13. George Overbury Hart (1868 – 1933). He evidently acquired the nickname “Pop” as he was several years older than most of the other artists with whom he mixed. For a detailed and excellent account of Hart’s life and work, see Gilbert, op cit.

14. McMartin, op cit at 34.

15. Reed, W (ed), The Illustrator in America; 1900-1960s, Reinhold Pub Corp, New York 1966, at 34.

16. Sarka, op cit at 1, 2.

17. Sarka, op cit at 2.

18. Pop Hart had a decidedly eccentric streak. According to one almost-certainly apocryphal story, his friend Rudi Dirks and a group of other American painters once invited Hart to stay with them in Munich. When he arrived, he only had a little money, but spent it all on a top hat and a walking stick. Each night, after he had gone to sleep, they would get the cane, remove the ferrule, saw off an inch of the stick and put the ferrule back. The stick grew shorter and shorter. One day while out walking, Pop stopped in his tracks. “Fellows,” he said, “this is a wonderful climate over here. Do you know, I believe I’ve grown six inches since I came to this town!” [http://john-adcock.blogspot.com/2009/09/rudy-gus-and-john-dirks.html]

19. Langdon, op cit at 95. Hart arrived just two months after Gauguin had died, in the neighbouring Marquesas Islands.

20. Cited in Gilbert, op cit at 113 fn 18. “Spoon hooks” are a type of fish hook.

21. Sarka, op cit at 4.

22. Edmond, R, Representing the South Pacific: Colonial Discourses from Cook to Gauguin, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997, at 2, 3.

23. The first European visitors were the British, under the command of Samuel Wallis, in June 1767. They were followed by the French expedition led by Louis -Antoine de Bougainville in 1768 . In A Voyage Round the World (1772). Bougainville dubbed Tahiti as “the New Cythera”, after the island where Aphrodite rose from the sea.

24. Burrows, E G, Hawaiian Americans: An Account of the Mingling of Japanese, Chinese, Polynesian and American Cultures, Archer Books, 1970, at 99; Whitehead, J S, “Writers as Pioneers” in Gibson, op cit at 379.

25. Whitehead, in Gibson, op cit at 382. John Ledyard, a sailor with Cook, wrote a Journal of Captain Cook’s Last Voyage to the Pacific Ocean (1783), portraying Hawaii as a hospitable island with friendly inhabitants. Cook’s little fatal incident there was glossed over, as Ledyard had a commercial interests in Hawaii that he was keen to promote.

26. Whitehead, in Gibson, op cit at 382 ff; Claire Harman, Robert Louis Stevenson: A Biography, Harper Perennial, London, 2005 at 354 ff.

27. Adams wrote the nine-volume History of the United States of America during the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison (1870-77).

28. Like many artists prominent in the 19th century, La Farge’s reputation has suffered a substantial decline. In his heyday he was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honour by the French Government and the presidency of the National Society of Mural Painters. He was one of the first seven artists chosen for membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

29. Tahiti Memoirs of Marua Taaroa, Last Queen of Tahiti (1893).

29A. See La Farge, H, “John La Farge and the South Sea Idyll”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 7, (1944), pp. 34-39. For an account of La Farge’s visit, see John La Farge: Watercolors and Drawings (Exh Cat) Yarnell, JL, The Hudson River Museum of Westchester, NY, 1990, at 49ff.

30 There is an odd passing reference to Gauguin in Sarka, op cit at 8, where Sarka mentions walking “past La Vina’s door, but Gauguin had gone to the Marquesas”. It appears from this as if Sarka was hoping to meet him but, of course, Gauguin was dead by this time.

31. Sarka, op cit at 4.

32. Sarka, op cit at 54. Stevenson had stayed in Tautira for two months in 1886 to recuperate from an illness and was rhapsodic about its beauty, describing it as “mere heaven” and “the garden of the world”: Robert Louis Stevenson: his best Pacific writing, Robinson R (ed), University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 2004 at 62ff.

32A. See generally Gilbert, op cit at 18.

33. Sarka, op cit at 5.

34. Langdon, op cit at 95, citing an interview with Sarka reported in the Ashbury Park Sunday Press, Oct 1932.

35. Langdon, op cit at 95.

36. Sarka, op cit.

37. Langdon, op cit at 97.

38. Ibid.

39. Gilbert, op cit at 17, 18; Sarka, op cit.

40. Sarka, op cit at 53.

41. Langdon, op cit at 97.

42. Sarka, op cit at 26.

43. Ibid at 18.

44. Ibid at 27.

45. Ibid at 85.

46. Ibid at 18.

47. Ibid at 45.

48. Ibid at 52.

49. Ibid at 87.

50. Ibid at 28.

51. Ibid at 33.

52. Ibid at 47.

53. Ibid at 29.

54. Ibid at 34.

55. Ibid at 37.

56. Ibid at 16.

57. Edmonds, op cit at 257.

58. Sarka, op cit at 102.

59. Smith, B, European Vision and the South Pacific, 2 ed, Harper & Row, Sydney 1985, ch 11.

60. Edmonds, op cit at 249.

61. Langdon, op cit at 97. In some of the secondary literature, there are also references to Sarka being commonly known as the “American Gauguin”. This appears to be incorrect. The description has been variously applied to miscellaneous artists, such as Bernhard Gutman, Maurice Stern, Andrew Glass and even Pop Hart himself. It is most commonly bestowed on Edgar Leeteg, who acquired a ludicrously inflated reputation based on his paintings of bare-breasted Polynesian maidens on black velvet.

62. New York Times, 28 Jan 1906.

63. Sarka, op cit, Introduction at 3, 4.

64. New York Times, 12 October 1902.

65. New York Times, 2 January 1921.

66. Sarka, op cit Introduction at 5; Gilbert, op cit at 32.

67. Letter to Paul Bransom, 18 April 1917, reproduced in Kirwin, L, More Than Words: Illustrated Letters from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, Princeton Architectural Press, 2005, at 40.

68. Sarka, op cit at 72. A similar account appears in a Journal which Sarka kept during his visit to Tahiti in 1903 (McMartin, op cit at 35). This journal is held with Sarka’s papers in the Archives of American Art. Adapted parts of this, such as this particular episode, eventually found their way into Tahiti Nui, which was written about 20 years later. Probably for this reason, the two works are sometimes confused.

69. The literary device of using Polynesian elders as a cultural archive has a long history in Western representations of the Pacific: see Edmonds, op cit at 253.

70. Sarka, op cit at 74.

71. New York Times, “Art Colony has a Trial by Fire”, 5 March 1914..

72. Crawford, op cit at 141.

73. Crawford, op cit at 144.

74. Kirwin, op cit at 40: http://www.aaa.si.edu/exhibitions/illustrated-letters#134

75. Details of this work appeared on the archived website of the exhibiting gallery, Jack the Pelican, of Williamsburg in New York. The work is apparently owned by the ex-gallery’s director. Don Carroll. I have not been able to trace how it originally came into his possession.

76. McMartin, op cit at 36; Crawford, op cit at 142.

77. Some of the residents’ summer parties at Canada Lake, even after Prohibition had been introduced, were anything but sober. James Thurber, a constant visitor, once stepped off an unfinished porch and fell into the rocky water. His plight went unnoticed until the party-goers eventually heard a faint voice calling for his wife: “Althea… Althea”, came the plaintive cry, “Here I am, down among the goldfish.”(McMartin, op cit at 37). For an interesting record of the Canada Lake community, where artists, writers and filmmakers “would work diligently during the day and party with wild abandon at night”, see Smalley, C P, Images of America: Around Caroga Lake, Canada Lake and Pine Lake (Arcadia, South Carolina 2011).

78. It is reported that the earliest known artist to work round Canada Lake was Rufus Alex Grider. 9

79. McMartin, op cit at 36.

80. Crawford, op cit at 144.

80A.The 1930 launch of Life magazine, with its exclusively photograph-based content, "signalled the triumph of the camera over the paintbrush, of the machine over the hand, of the darkroom over the atelier, of speed over slowness": Deborah Solomon, American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, 2013 at 177.

81. McMartin, op cit at 38. McMartin was told this in a personal interview with Bransom.

82. Crawford, op cit at 144.

83. McMartin, op cit at 38; Crawford, op cit at 142.

84. McMartin, op cit at 34.

85. Crawford, op cit at 142.

86. Langdon, op cit at 93.

87. Furia , L A de, “Charles Sarka (1879-1960) Aquarellist”, New Jersey Music and Arts, Vol 27 no 3 June 1974 p 16, cited in Crawford, op cit at 142. Despite efforts, I have not been able to access this article.

88. Extraordinary Visions: The Watercolor Tradition of Charles Sarka, Canajoharie Library and Art Gallery, New York, November/December 1999.

89. The Jack the Pelican website, op cit (note 75), says that the 1963 show sold out, “with works going to major American Museums, including the Metropolitan, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Whitney. The only one to get into private hands went to then First Lady Jackie Kennedy”. On the other hand, McMartin, op cit at 35, says that the major museum acquisitions occurred in the 1920s, at the peak of Sarka’s career. According to the accession records for the Metropolitan, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Brooklyn Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, these bodies acquired the works from the 1960s onwards, by way of gift.

90. Langdon, op cit at 93.

91. Crawford, op cit at 140.

92. McMartin, op cit at 35; Crawford, op cit at 144.

93. Sarka, op cit at 72.

94. McMartin, op cit at 38.

95. Crawford, op cit at 144.

Back to HOME

2. This account is based on correspondence over the period 1967-1969 received by Robert Langdon, the Executive Officer of the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, Canberra. Copies of this correspondence were kindly made available by the Bureau.

3. The article was “America’s Art Lovers Discover ‘Sarka of the South Seas’”, Pacific Islands Monthly, Dec 1966, 93. Langdon had also written a history, Tahiti - Island of Love, first published in 1959. A good part of his early work with the Bureau focused on Tahitian documents. He died in 2003.

4. Crawford has suggested that the reason that the book was not originally published back in the 1920s or 1930s was that it was entirely in the form of a Socratic dialogue (Crawford, J, “The Watercolour Tradition of Charles Sarka”, American Art Review, Vol XI No 6 (Dec 1999), 140 at 144). However there is only one short section in Tahiti Nui that could be described in this way.

5. There is another copy in the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian.

6. The year 2010 represented the 50th anniversary of Sarka’s death in 1960.

7. His middle name is sometimes misspelled as “Nicholas”.

8. McMartin, B, “Sure Strokes on a Bright Canvas”, Adirondack Life, Vol XXVI, No 5 (July /August 1995) at 34.

9. Langdon, R, “America’s Art Lovers Discover ‘Sarka of the South Seas’”, Pacific Islands Monthly, Dec 1966, 93 at 95

10. Or, alternatively, at age 22 according to Gilbert, G, George Overbury “Pop” Hart: His Life and Art, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 1986, at 13.

11. Sarka, op cit, Introduction p 1, 2. For the sake of clarity, some minor subediting changes have been made to some of the quotations from Tahiti Nui in this article.

12. Crawford, op cit at 140.

13. George Overbury Hart (1868 – 1933). He evidently acquired the nickname “Pop” as he was several years older than most of the other artists with whom he mixed. For a detailed and excellent account of Hart’s life and work, see Gilbert, op cit.

14. McMartin, op cit at 34.

15. Reed, W (ed), The Illustrator in America; 1900-1960s, Reinhold Pub Corp, New York 1966, at 34.

16. Sarka, op cit at 1, 2.

17. Sarka, op cit at 2.