“ALL LIFE IS HERE”: Bruegel’s Way to Calvary

By Philip McCouat For comments on this article, see here

INTRODUCTION

In the early 1800s, as Napoleon’s armies swept through Europe, one of his trusted advisers was put in charge of “requisitioning” the artworks of conquered countries and transporting them to Paris. This man, Vivant Denon, became the first Director of the recently-opened Louvre Museum, which would become the repository for hundreds of these works [1].

By 1815, however, following Napoleon’s fall, many of those works – but by no means all – started to be returned to their original owners. One of the most extraordinary of these restored works was a painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, widely regarded as the 16th century’s greatest Netherlandish artist. It is this painting, The Way to Calvary [2], now in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum [3], that we shall be exploring in this article.

By 1815, however, following Napoleon’s fall, many of those works – but by no means all – started to be returned to their original owners. One of the most extraordinary of these restored works was a painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, widely regarded as the 16th century’s greatest Netherlandish artist. It is this painting, The Way to Calvary [2], now in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum [3], that we shall be exploring in this article.

SETTING THE SCENE

The overall view

The Way to Calvary (1564) is the second largest painting that Bruegel ever did [4]. It was probably commissioned by Bruegel’s patron Niclaes Jonghelinck, who also commissioned many others of his works, such as the Tower of Babel and Hunters in the Snow.

The painting is about the size of a dining tabletop (124 x 170 cm) and features a mass of humanity, with literally hundreds of individual characters, in a setting more reminiscent of Northern Europe than of the Middle East. Such a treatment was not radically new – it had been customary since Jan van Eyck to depict the procession to Calvary with a multitude of figures in contemporary costumes in a familiar European landscape [5]. But Bruegel’s version here is truly exceptional because of his skill in convincingly portraying such a variety of closely-observed incident, with such a vividness of characterisation [6].

Because of the painting’s size and the multitude of characters, it is easy to get lost and lose track of what is really going on. To enable you to keep your bearings, and provide a context to aid location, we have here divided the painting into 12 sectors (Fig 2). These sectors are in three rows of four, so that sector 1 is at top left of the painting and sector 12 is at bottom right. We will be referring to these often throughout this article.

The Way to Calvary (1564) is the second largest painting that Bruegel ever did [4]. It was probably commissioned by Bruegel’s patron Niclaes Jonghelinck, who also commissioned many others of his works, such as the Tower of Babel and Hunters in the Snow.

The painting is about the size of a dining tabletop (124 x 170 cm) and features a mass of humanity, with literally hundreds of individual characters, in a setting more reminiscent of Northern Europe than of the Middle East. Such a treatment was not radically new – it had been customary since Jan van Eyck to depict the procession to Calvary with a multitude of figures in contemporary costumes in a familiar European landscape [5]. But Bruegel’s version here is truly exceptional because of his skill in convincingly portraying such a variety of closely-observed incident, with such a vividness of characterisation [6].

Because of the painting’s size and the multitude of characters, it is easy to get lost and lose track of what is really going on. To enable you to keep your bearings, and provide a context to aid location, we have here divided the painting into 12 sectors (Fig 2). These sectors are in three rows of four, so that sector 1 is at top left of the painting and sector 12 is at bottom right. We will be referring to these often throughout this article.

Once we get over the initial impression of chaotic activity, we can see that the narrative in the painting unfolds from left to right. The gold-bathed walled town that we can just make out in the misty distance (Fig 3; sector 1) is a rather Netherlandish version of Jerusalem where, the previous day, Jesus’s trial had taken place. Above the city, the sun shines brightly, the sky is light, and the surrounding foliage is healthy and green.

People are leaving the city, making their way up across the fields. Numerous puddles and mud on the ground tell us it has recently been raining. The long shadows of the individuals in the crowd tell us it is early morning [7] and people holding onto their hats show that there is a brisk breeze blowing (see group at right in Fig 15). As we continue to look right, we can follow the line of the red-coated horsemen, past the precipitous windmill crag (sector 2), and directly to the fallen Christ. He is almost hidden, right in the middle of the painting (sectors 6,7), fallen exhausted under the weight of the Cross, while the two thieves just ahead of him sit petrified in the horse-drawn tumbril. In the sky directly above them, ominous dark clouds have gathered, reflecting Biblical accounts that the sky darkened during the execution (sector 3).

All around them are vignettes of life in the crowd. Some of them are eager to catch sight of or mock the main actors, but most are content to attend to their own devices, or on the lookout for other diversions until the main action of the execution begins. Here, in an era in which the life of ordinary people was hard and often short, the ritualised suffering and death of malefactors was a form of popular entertainment, akin to a festival or carnival. It was a tradition which would continue in various parts of Europe well into the 19th century.

Those eager to get a good view of the execution straggle up towards the hill of Calvary in the far distance at right, where an expectant crowd has already gathered (sector 4). In the right foreground, meanwhile, Mary and the holy group, with their backs to all that is going on, are grieving (sectors 11, 12). There is little green foliage in this part of the painting, just a thistle (a Christian symbol) growing right in the corner, a skull on the rock (reflecting the meaning of Calvary as a "hill of skulls"), the barren tree-trunk holding the macabre torture wheel on the right edge (sectors 4,8), and the spindly trees that we can just make out on the hill of Calvary in the distance. The transition from life (on the left of the painting) to death (on the right of the painting) could hardly be made more explicit.

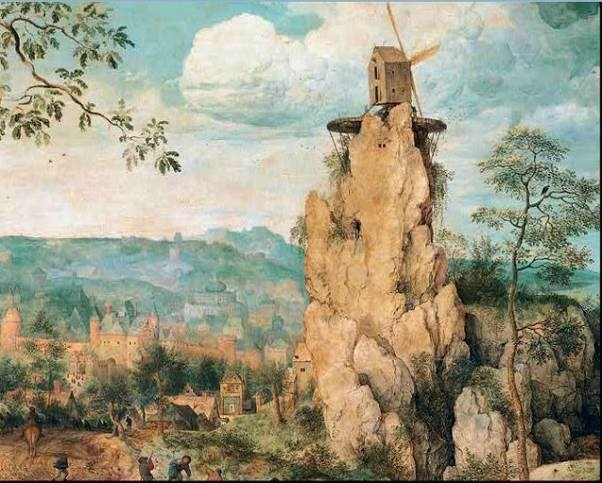

The crag with the windmill

Dominating the top left of the painting is the extraordinarily precipitous rocky crag (Fig 4; sector 2). Such crags were a common feature in Flemish depictions of the carrying of the Cross [8]. Bruegel’s version here is topped with a windmill perched on a platform that, oddly, reflects the shape the torture wheels that are scattered throughout the painting.

All around them are vignettes of life in the crowd. Some of them are eager to catch sight of or mock the main actors, but most are content to attend to their own devices, or on the lookout for other diversions until the main action of the execution begins. Here, in an era in which the life of ordinary people was hard and often short, the ritualised suffering and death of malefactors was a form of popular entertainment, akin to a festival or carnival. It was a tradition which would continue in various parts of Europe well into the 19th century.

Those eager to get a good view of the execution straggle up towards the hill of Calvary in the far distance at right, where an expectant crowd has already gathered (sector 4). In the right foreground, meanwhile, Mary and the holy group, with their backs to all that is going on, are grieving (sectors 11, 12). There is little green foliage in this part of the painting, just a thistle (a Christian symbol) growing right in the corner, a skull on the rock (reflecting the meaning of Calvary as a "hill of skulls"), the barren tree-trunk holding the macabre torture wheel on the right edge (sectors 4,8), and the spindly trees that we can just make out on the hill of Calvary in the distance. The transition from life (on the left of the painting) to death (on the right of the painting) could hardly be made more explicit.

The crag with the windmill

Dominating the top left of the painting is the extraordinarily precipitous rocky crag (Fig 4; sector 2). Such crags were a common feature in Flemish depictions of the carrying of the Cross [8]. Bruegel’s version here is topped with a windmill perched on a platform that, oddly, reflects the shape the torture wheels that are scattered throughout the painting.

Compositionally, Bruegel’s windmill crag plays an important role by acting like an axle, around which all the action slowly turns, mirroring the action of the windmill’s sails themselves. But there has been much speculation that it may have some deeper meaning here. Perhaps it is political -- maybe the mill is there because of its status as an iconic emblem of Flanders which continues despite the Spanish regime. Perhaps it is religious – Michael Gibson, for example, suggests that the crag resembles a cathedral tower, crowned with a Cross formed by the crossed sails of the windmill. On his interpretation, the mill is founded on a rock, like the institution of the Church itself.

Or perhaps the mill is intended to be interpreted in a cosmological sense, standing for the “rotation of the world with its attendant sequence of cataclysms and renewals”. It has even been argued that the mill could be a symbol of the all-seeing eye of God watching the world from on high [9].

The place of execution

At the hill of Calvary [10], the place of execution, we see a large open space dotted with corpse-strewn torture wheels (Fig 5; sector 4).

Or perhaps the mill is intended to be interpreted in a cosmological sense, standing for the “rotation of the world with its attendant sequence of cataclysms and renewals”. It has even been argued that the mill could be a symbol of the all-seeing eye of God watching the world from on high [9].

The place of execution

At the hill of Calvary [10], the place of execution, we see a large open space dotted with corpse-strewn torture wheels (Fig 5; sector 4).

People have already gathered in a large circle (Fig 6; sector 4). There are children, dogs and horses scattered throughout the crowd. The crosses for the two thieves are already in place, their uprights echoing the uprights of the torture wheels and the trunks of the trees in the background. A worker is busy digging a hole for the cross that Jesus will bring with him. A red-coated trooper keeps the crowd back.

As with Christ himself, this place is inconspicuous, though in this case it is because of the distance from the viewer. But Bruegel ensures that we cannot miss it -- our eyes are led by the people straggling up the hill and by the torture wheel at the far right of the painting, mirroring the circle of spectators where a scavenging crow is perching, and a scrap from the remains of a corpse still flutters in the breeze.

JESUS, THE THIEVES AND THE SOLDIERS

Jesus and the thieves

Although Jesus appears in the very centre of the painting, he can be remarkably difficult to find (Fig 6; sectors 6,7)[11]. Bruegel gives him few of the usual identifying signs – just the mocking crown of thorns, but no halo, no spiritual eminence, no hint that he is intended to be the son of God. Instead, he is clad in a simple blue cloak and has fallen dazed and exhausted to the ground, unable to carry the heavy cross [12]. Around him, there appears to be some confusion, with some of the executioners pulling the cross, some pushing, with one man even resting his foot on the upright. Another, exotically-dressed, lead the way, blowing a curved horn, mockingly heralding the supposed Messiah [12A]. Remarkably, few of those around Christ are actually looking at him. This, coupled with his small size, is apparently intended to highlight the general indifference to his suffering.

Although Jesus appears in the very centre of the painting, he can be remarkably difficult to find (Fig 6; sectors 6,7)[11]. Bruegel gives him few of the usual identifying signs – just the mocking crown of thorns, but no halo, no spiritual eminence, no hint that he is intended to be the son of God. Instead, he is clad in a simple blue cloak and has fallen dazed and exhausted to the ground, unable to carry the heavy cross [12]. Around him, there appears to be some confusion, with some of the executioners pulling the cross, some pushing, with one man even resting his foot on the upright. Another, exotically-dressed, lead the way, blowing a curved horn, mockingly heralding the supposed Messiah [12A]. Remarkably, few of those around Christ are actually looking at him. This, coupled with his small size, is apparently intended to highlight the general indifference to his suffering.

According to Biblical accounts, Jesus was crucified with two thieves [13]. They are not required to carry their crosses here, but sit in a cart, apparently frightened out of their wits, with two priests attending, one Dominican, the other Franciscan (Fig 9; sector 7). The ashen-faced thief in front looks to the sky with unseeing eyes, the other sits dejected and dazed. He is holding a crucifix in his tied hands, an extraordinary anachronism given that Jesus had not even been crucified yet [14], but a reminder that the Cross was not just a symbol of painful death and suffering, but also a powerful vehicle of consolation.

The cart carrying the thieves, mud dripping from its wheels [15], is crossing a stretch of water – possibly echoing the river Styx [16] – just before heading uphill towards its occupants’ fate. The way ahead of them is studded with the mounted torture wheels we have already seen in Fig 5, where the corpses of previous victims have been left to rot, or gibbets with hanging corpses.

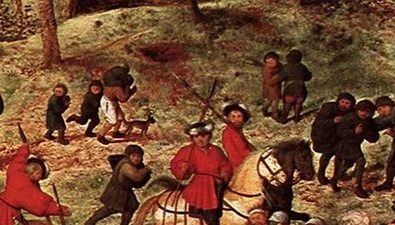

The red-coated Spanish

Just as Bruegel presents a very Flemish version of Jerusalem, he has also presented a Spanish version of the Roman soldiers who, historically, would have been in charge of the execution.

In Bruegel’s time, the Netherlands were under the control of Spain, much to the fear and hatred of the mostly Protestant inhabitants. Spanish rule was harsh, and there was ruthless religious persecution. Bruegel has tellingly depicted the troopers supervising the day’s proceedings as the hated roode rocx (red-coats), the Walloon mercenary horsemen who were in the service of the Spanish king. (They also appear in Bruegel’s Massacre of the Innocents [17]).

These red coats also play a compositional role. They stretch from the left all the way to the hill of Calvary, mirroring the left-to-right structure of the painting. To hammer home the Spanish reference, the horseman riding ahead of the cart with the thieves carries a pale pink flag (Fig 9; sector 7). We can just make out the faint outline of the Habsburg double eagle embroidered in gold thread.

The red-coated Spanish

Just as Bruegel presents a very Flemish version of Jerusalem, he has also presented a Spanish version of the Roman soldiers who, historically, would have been in charge of the execution.

In Bruegel’s time, the Netherlands were under the control of Spain, much to the fear and hatred of the mostly Protestant inhabitants. Spanish rule was harsh, and there was ruthless religious persecution. Bruegel has tellingly depicted the troopers supervising the day’s proceedings as the hated roode rocx (red-coats), the Walloon mercenary horsemen who were in the service of the Spanish king. (They also appear in Bruegel’s Massacre of the Innocents [17]).

These red coats also play a compositional role. They stretch from the left all the way to the hill of Calvary, mirroring the left-to-right structure of the painting. To hammer home the Spanish reference, the horseman riding ahead of the cart with the thieves carries a pale pink flag (Fig 9; sector 7). We can just make out the faint outline of the Habsburg double eagle embroidered in gold thread.

THE SPECTATORS

A multitude of characters and incident

In the painting, we are looking at hundreds of individuals. Aside from the main actors, there are peasants, tradesmen, agricultural and town workers, clerics, soldiers, artisans, beggars and gypsies – all in contemporary Flemish dress -- not to mention forty horses, numerous birds and at least eight dogs.

Such is the detail that some scenes can only be identified under magnifying glass. Everywhere one looks there is lively incident – from the far left of the painting, where a white-bonneted woman pushes a sled carrying a wicker basket with two calves, evidently intended for market (sector 5), to the slopes of the hill of Calvary, where a white horse being ridden by a merchant bucks in alarm as a peasant’s hat blows off in its path (sector 7).

A reluctant Simon

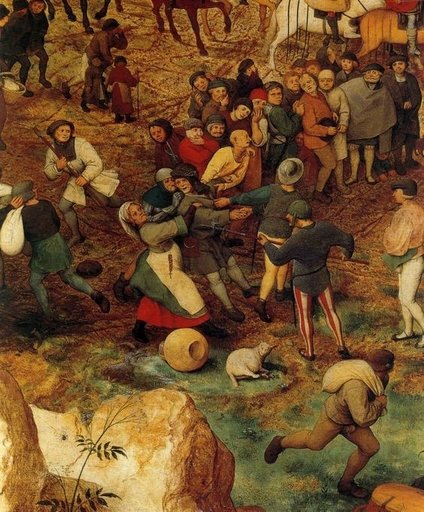

Within this bewildering array of activity, let us focus in more detail on just a few vivid vignettes. In the left foreground, for example, a fight has broken out (Fig 10: sectors 9,10) [18]. A soldier with red and white striped tights jabs his pike at a woman. She is trying to hold onto her husband (in grey and black), who is being dragged away by two other soldiers. She has dropped her jug of milk, just as her husband has dropped the bound sheep. Members of the crowd look on, with expressions ranging from interest to fear. Three workmen with full sacks, evidently intended for market, are running off, and a shepherd holding a crook is also making himself scarce.

In the painting, we are looking at hundreds of individuals. Aside from the main actors, there are peasants, tradesmen, agricultural and town workers, clerics, soldiers, artisans, beggars and gypsies – all in contemporary Flemish dress -- not to mention forty horses, numerous birds and at least eight dogs.

Such is the detail that some scenes can only be identified under magnifying glass. Everywhere one looks there is lively incident – from the far left of the painting, where a white-bonneted woman pushes a sled carrying a wicker basket with two calves, evidently intended for market (sector 5), to the slopes of the hill of Calvary, where a white horse being ridden by a merchant bucks in alarm as a peasant’s hat blows off in its path (sector 7).

A reluctant Simon

Within this bewildering array of activity, let us focus in more detail on just a few vivid vignettes. In the left foreground, for example, a fight has broken out (Fig 10: sectors 9,10) [18]. A soldier with red and white striped tights jabs his pike at a woman. She is trying to hold onto her husband (in grey and black), who is being dragged away by two other soldiers. She has dropped her jug of milk, just as her husband has dropped the bound sheep. Members of the crowd look on, with expressions ranging from interest to fear. Three workmen with full sacks, evidently intended for market, are running off, and a shepherd holding a crook is also making himself scarce.

A well-dressed noble, with a pink shirt, watches proceedings with a proprietorial air, while other notables wait for the matter to be calmed down. They have an interest in this -- the husband is probably the biblical Simon of Cyrene, who is being press-ganged into helping Christ carry the too-heavy cross. The wife’s resistance to his helping Christ can be seen as hypocritical, given that she has a rosary at her hip. The trussed lamb, lying next to the overturned clay pot at the wife's feet, is a symbol of martyrdom [18A].

The wandering pedlar

Even closer in the foreground, seated with his back to us, is a pedlar with bag of wares on his back, holding a stave and wearing a cap with a jaunty feather (Fig 11: sector 10). He seems slightly abstracted, both physically and emotionally, from the rest of the spectators. It has been suggested that this man is one of the wandering pedlars, often selling bread, who disseminated forbidden Anabaptist writings that were kept in the bottom of their bags [19].

The wandering pedlar

Even closer in the foreground, seated with his back to us, is a pedlar with bag of wares on his back, holding a stave and wearing a cap with a jaunty feather (Fig 11: sector 10). He seems slightly abstracted, both physically and emotionally, from the rest of the spectators. It has been suggested that this man is one of the wandering pedlars, often selling bread, who disseminated forbidden Anabaptist writings that were kept in the bottom of their bags [19].

It has also been suggested that the group at the foot of the torture wheel at far right (Fig 12; sector 12) includes a grim-faced Anabaptist preacher (in black), together with a self-portrait of a somewhat neutral-looking Bruegel (pale coat and brown cap).

The holy group and the women

Tucked away in the right foreground of the painting is a discrete group which is quite different from, and larger than, the other far more rustic spectators (Fig 13; sectors 11, 12). This group are expensively dressed in idealised apparel from an earlier era [19A], delicately drawn and drowned in sorrow. They have turned away from the spectacle. St John is standing, leaning forward to support an ashen-faced Mary, while two other holy women – including a magnificently-clad Mary Magdalene at left -- kneel in prayer or grief [20].

Tucked away in the right foreground of the painting is a discrete group which is quite different from, and larger than, the other far more rustic spectators (Fig 13; sectors 11, 12). This group are expensively dressed in idealised apparel from an earlier era [19A], delicately drawn and drowned in sorrow. They have turned away from the spectacle. St John is standing, leaning forward to support an ashen-faced Mary, while two other holy women – including a magnificently-clad Mary Magdalene at left -- kneel in prayer or grief [20].

It is almost as if this is a quite different painting, in a quite different style, underlying Bruegel’s desire to differentiate the group from the hoi polloi. Compositionally, however, he links the holy group to other aspects of the scene. The roughly triangular shape of the grouped figures is balanced by the similar shape of the rocky outcrop in the left foreground; and the shape formed by St John and Mary echoes the shape of the high rocky outcrop in the distance.

Emotionally, too, they are linked to four other women who form a line leading towards the torture wheel at the right -- a woman watching the spectacle with her arms outstretched in commiseration, another with burying her face in her apron (both of these appear in Fig 14), a third with her hands clasped watching the procession, and an older woman, her mouth open, with a look of shocked outrage [21].

Emotionally, too, they are linked to four other women who form a line leading towards the torture wheel at the right -- a woman watching the spectacle with her arms outstretched in commiseration, another with burying her face in her apron (both of these appear in Fig 14), a third with her hands clasped watching the procession, and an older woman, her mouth open, with a look of shocked outrage [21].

Apart from these women and Simon’s wife, there are only a few women in the painting, and seemingly none on the actual hill of Calvary. Many of them appear to have been simply caught up in the procession while they were on their way to market. Those paying attention generally look compassionate, in contrast to most of the men -- for example the two women, quite close to Jesus, with their backs to us, with hands held up (sector 7).

Children at play

The children scattered throughout the painting are largely oblivious to the momentous events that are unfolding. Instead, like children everywhere, they are mainly absorbed in their own worlds of exploration, play and just general messing round.

Just to the left of the windmill crag, a group of boys are skylarking in the mud (sectors 5, 6). One tries to pole vault over the muddy puddles, another holds his baby sister as he manoeuvres to dry land, and two others check how much mud they’ve collected on their stockings (at left of Fig 15).

Children at play

The children scattered throughout the painting are largely oblivious to the momentous events that are unfolding. Instead, like children everywhere, they are mainly absorbed in their own worlds of exploration, play and just general messing round.

Just to the left of the windmill crag, a group of boys are skylarking in the mud (sectors 5, 6). One tries to pole vault over the muddy puddles, another holds his baby sister as he manoeuvres to dry land, and two others check how much mud they’ve collected on their stockings (at left of Fig 15).

Over on the other side of the painting, just behind the holy group, a barefoot girl lifts the folds of her blue shift as she cautiously paddles toward her more impetuous brother (Fig 16; sector 11). Further over to the right, a child rides on its father’s shoulders (sector 12).

Behind the fallen Christ, we see two children, accompanied by their load-bearing mother and a dog, who look back at the action (Fig 17; sector 6). But the “action” is not what you might expect. For them, as for many others in the crowd, the fracas that surrounds Simon of Cyrene (sectors 9,10) occupies their interest far more than does the fate of stricken Christ.

Conclusion

Unlike so many painters of traditional religious subjects, Bruegel has firmly rooted his biblical story in ordinary, contemporaneous life. His conception of the real setting in the Middle East would in any event have been sketchy at best, so he sets it in a recognisable Flanders landscape and peoples it with a teeming diversity of ordinary local people, depicting them with a discerning and sympathetic appreciation of normal human foibles and weaknesses, and eschewing many of the conventional motifs of holiness and divinity. It is the very ordinariness and humanity of his depiction, and the indifference or casual cruelty with which Christ is being treated, that brings home to the viewer the awfulness and significance of the tragedy that is slowly unfolding before them.

© Philip McCouat 2017, 2021. First published June 2017.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “All life is here”: Bruegel’s Way to Calvary, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

Other articles on Bruegel that you may enjoy are:

Back to HOME

© Philip McCouat 2017, 2021. First published June 2017.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “All life is here”: Bruegel’s Way to Calvary, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

Other articles on Bruegel that you may enjoy are:

- Bruegel’s Icarus and the Perils of Flight

- The emergence of the winter landscape

- Bruegel's Bruegel's Peasant Wedding Feast

- Perception and Blindness

- Bruegel's Tower of Babel

- Bruegel's White Christmas: The Census at Bethlehem

Back to HOME

End Notes

[1] From 1809-15 it was renamed the Musée Napoleon.

[2] Also known as The Procession to Calvary (a painting under that title was also done by his son Pieter Brueghel the Younger) and Christ Carrying the Cross. Calvary is also known as Golgotha.

[3] Of the forty or so of Bruegel’s works that still exist today, twelve of them are in just one room, at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. In 2019, a major retrospective exhibition featuring Pieter Bruegel the Elder was held at that Museum to mark the 450th anniversary of the artist’s death.

[4] The biggest is the recently-attributed Wine of St Martin’s Day, c 1565.

[5] Alexander Wied, Bruegel (transl Anthony Lloyd), Bay Books, Sydney 1980 at 126.

[6] The painting has inspired an extraordinary 2011 feature film, The Mill & the Cross. The film is based on the book of the same name by the art historian/critic Michael Francis Gibson, whose work I have drawn on heavily in this article. You can find my reviews of the film HERE and of the book HERE.

[7] Michael Francis Gibson, The Mill and the Cross, University of Levana Press, expanded edn 2012 at 17.

[8] See, for example, the Brunswick Monogamist's The Road to Calvary (mid 16C).

[9] Gibson, op cit at 49, 53.

[10] Also known as Golgotha, “the Place of the Skull” (see for example Matthew 27:33). The Latin for skull is calvaria.

[11] Bruegel uses this device of obscuring the whereabouts of the main actor in a number of paintings; see for example The Census at Bethlehem, and The Fall of Icarus (discussed further in our article on that painting).

[12] In fact, the normal Roman practice would have been to require the person to carry only the crossbar, with the upright being already erected at the place of execution. The weight of the entire cross would have been considerable, and it would be difficult for one man to carry it any distance, let alone someone like Jesus who had already been whipped shortly before. For a detailed examination of the role of the Cross in Christian thought, see Robin M Jensen, The Cross: History, Art and Controversy, Harvard University Press. 2017.

[12A] Oberthaler et al, Bruegel; The Master, Thames & Hudson, 2018, at 200.

[13] Matt 27:44; Luke 23:39-43.

[14] Gibson, op cit at 84.

[15] Timothy Foote, The World of Bruegel: 1525-1569, Time- Life International (Nederland) NV, 1971 at 110.

[16] Gibson, op cit at 83.

[17] Wied, op cit at 127.

[18] Gibson, op cit at 12, 77.

[18A] Mary's blue robe has faded, due to Bruegel's use of the unstable pigment smalt: Oberthaler, op cit at 201 footnote 11.

[19] Wied, op cit at 128 citing M Auner, Pieter Bruegel: Umrisse eines Lebensbildes, in Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien, 52, XVI, 1956 at 51. Interestingly, a similar figure also appears in the far left of Pieter Aertsen’s earlier version of Christ Carrying the Cross (1552).

[19A] Oberthaler, op cit at 201 footnote 17.

[20] See generally Gibson, op cit at 103ff.

[21] Gibson, op cit at 104.

© Philip McCouat 2017, 2021

Back to HOME

[2] Also known as The Procession to Calvary (a painting under that title was also done by his son Pieter Brueghel the Younger) and Christ Carrying the Cross. Calvary is also known as Golgotha.

[3] Of the forty or so of Bruegel’s works that still exist today, twelve of them are in just one room, at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. In 2019, a major retrospective exhibition featuring Pieter Bruegel the Elder was held at that Museum to mark the 450th anniversary of the artist’s death.

[4] The biggest is the recently-attributed Wine of St Martin’s Day, c 1565.

[5] Alexander Wied, Bruegel (transl Anthony Lloyd), Bay Books, Sydney 1980 at 126.

[6] The painting has inspired an extraordinary 2011 feature film, The Mill & the Cross. The film is based on the book of the same name by the art historian/critic Michael Francis Gibson, whose work I have drawn on heavily in this article. You can find my reviews of the film HERE and of the book HERE.

[7] Michael Francis Gibson, The Mill and the Cross, University of Levana Press, expanded edn 2012 at 17.

[8] See, for example, the Brunswick Monogamist's The Road to Calvary (mid 16C).

[9] Gibson, op cit at 49, 53.

[10] Also known as Golgotha, “the Place of the Skull” (see for example Matthew 27:33). The Latin for skull is calvaria.

[11] Bruegel uses this device of obscuring the whereabouts of the main actor in a number of paintings; see for example The Census at Bethlehem, and The Fall of Icarus (discussed further in our article on that painting).

[12] In fact, the normal Roman practice would have been to require the person to carry only the crossbar, with the upright being already erected at the place of execution. The weight of the entire cross would have been considerable, and it would be difficult for one man to carry it any distance, let alone someone like Jesus who had already been whipped shortly before. For a detailed examination of the role of the Cross in Christian thought, see Robin M Jensen, The Cross: History, Art and Controversy, Harvard University Press. 2017.

[12A] Oberthaler et al, Bruegel; The Master, Thames & Hudson, 2018, at 200.

[13] Matt 27:44; Luke 23:39-43.

[14] Gibson, op cit at 84.

[15] Timothy Foote, The World of Bruegel: 1525-1569, Time- Life International (Nederland) NV, 1971 at 110.

[16] Gibson, op cit at 83.

[17] Wied, op cit at 127.

[18] Gibson, op cit at 12, 77.

[18A] Mary's blue robe has faded, due to Bruegel's use of the unstable pigment smalt: Oberthaler, op cit at 201 footnote 11.

[19] Wied, op cit at 128 citing M Auner, Pieter Bruegel: Umrisse eines Lebensbildes, in Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien, 52, XVI, 1956 at 51. Interestingly, a similar figure also appears in the far left of Pieter Aertsen’s earlier version of Christ Carrying the Cross (1552).

[19A] Oberthaler, op cit at 201 footnote 17.

[20] See generally Gibson, op cit at 103ff.

[21] Gibson, op cit at 104.

© Philip McCouat 2017, 2021

Back to HOME