FORGOTTEN WOMEN ARTISTS

#5 Thérèse Schwartze and the business of painting

By Philip McCouat For reader comments on this article, see here

This is the fifth in our series of articles discussing the lives and works of distinguished women artists from the past who have largely been forgotten. Other articles in the series have dealt with Arcangela Paladini, Jane Loudon, Marie-Gabrielle Capet and Michaelina Wautier

This is the fifth in our series of articles discussing the lives and works of distinguished women artists from the past who have largely been forgotten. Other articles in the series have dealt with Arcangela Paladini, Jane Loudon, Marie-Gabrielle Capet and Michaelina Wautier

Introduction

Thérèse Schwartze was a talented Dutch artist who achieved the peak of fame and success just over a century ago, only to fall back into deep obscurity, like so many women artists before her.

Schwartze made her name as a celebrated portraitist of the well-to-do, with clientele extending even to members of the Dutch Royal Family. Blessed with an extraordinary work ethic, considerable artistic talent, a pleasing manner and a good business sense, she amassed considerable wealth, more than fulfilling her teenage promise to her artist-father to support the family through her art. However, her star faded with the emergence of modern art movements in the early 20th century.

In this article, the 5th in our series on Forgotten Women Artists, we look at the challenges that Schwartze faced, the extraordinary way in which she overcame them, and the reasons for the dramatic decline in her reputation [1].

Schwartze made her name as a celebrated portraitist of the well-to-do, with clientele extending even to members of the Dutch Royal Family. Blessed with an extraordinary work ethic, considerable artistic talent, a pleasing manner and a good business sense, she amassed considerable wealth, more than fulfilling her teenage promise to her artist-father to support the family through her art. However, her star faded with the emergence of modern art movements in the early 20th century.

In this article, the 5th in our series on Forgotten Women Artists, we look at the challenges that Schwartze faced, the extraordinary way in which she overcame them, and the reasons for the dramatic decline in her reputation [1].

Early days / father’s influence / the breadwinner’s promise

Thérèse Schwartze was born in Amsterdam in 1851. Her father Johann Georg Schwartze was a successful portrait painter, and out of all the family members he quickly saw her as his natural successor. He began training her as an artist when she was just five years old, with the idea that she would ultimately become the main breadwinner in the family [2]. This was highly unusual at a time when middle-class women in Holland were simply expected to marry and live on their husbands' income.

Johann himself had grown up in the United States [3], and his forbears had endured many vicissitudes and changes of fortune; these evidently impressed upon him the importance of hard work, discipline, an entrepreneurial spirit and of seizing opportunity when the occasion arose [4]. He drilled his daughter assiduously, involving her in his own art practice, and ensured that she became totally focused on the task ahead. Remarkably, perhaps, she was happy to take on the rather daunting task she was set. When she was 16, she wrote to her father, “Ï will apply myself more to everything so as, with God’s blessing, to be able to earn by living by… painting, and I also hope I will not irritate you any more with foolish things, but will try to become a worthy daughter and to please you with my art” [5].

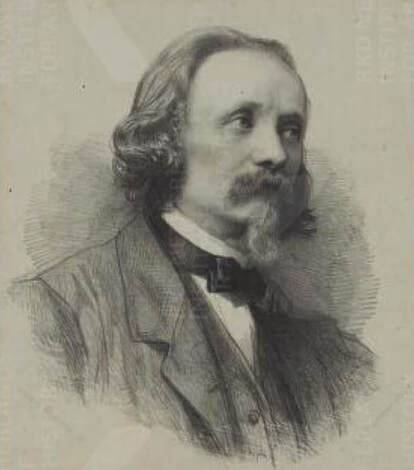

By the time she was 20, and with assistance from contacts made by her father, she began exhibiting, had some small sales, and attended classes in art history and theory at Amsterdam’s art academy. Her father’s death in 1874, commemorated by her in a lithograph (Fig 1) meant that she lost both teacher and role-model, though she would have felt fortified by his delight at the progress she was making – as he had noted satisfiedly shortly before his death, “Thérèse’s gift has developed at such a pace that she is now already painting as well as I ever did” [6].

Johann himself had grown up in the United States [3], and his forbears had endured many vicissitudes and changes of fortune; these evidently impressed upon him the importance of hard work, discipline, an entrepreneurial spirit and of seizing opportunity when the occasion arose [4]. He drilled his daughter assiduously, involving her in his own art practice, and ensured that she became totally focused on the task ahead. Remarkably, perhaps, she was happy to take on the rather daunting task she was set. When she was 16, she wrote to her father, “Ï will apply myself more to everything so as, with God’s blessing, to be able to earn by living by… painting, and I also hope I will not irritate you any more with foolish things, but will try to become a worthy daughter and to please you with my art” [5].

By the time she was 20, and with assistance from contacts made by her father, she began exhibiting, had some small sales, and attended classes in art history and theory at Amsterdam’s art academy. Her father’s death in 1874, commemorated by her in a lithograph (Fig 1) meant that she lost both teacher and role-model, though she would have felt fortified by his delight at the progress she was making – as he had noted satisfiedly shortly before his death, “Thérèse’s gift has developed at such a pace that she is now already painting as well as I ever did” [6].

Armed with financial and practical assistance secured from prominent art patron Carl Becker, she went to Munich to pursue her studies. Initially, she found it hard to obtain practical lessons from appropriate teachers and mentors. She felt that the general standard of teaching in special women’s classes “left much to be desired”, especially if the teacher did not also teach men. Women were also barred from painting from nude models, instead receiving lessons using dressed models, plaster casts, and even live cows, as befitting the perceived standards of “decency”. However, she eventually managed to receive invaluable tutelage and support [7], and stayed in Munich studying there for over a year.

The business of building her career

In 1877, when she returned to Amsterdam from Munich, she was 25 and “she immediately set about purposefully organising her career” [8].

From the outset, she determined to concentrate on portraits, the area in which she had received her training from her father. Portraiture had not been a major theme in Dutch art, but there were factors that made the time ripe for an artist of her talents [9]. It was an era of strong economic growth in the Netherlands, and a rising class of upper-middle class was emerging. The nouveau riche that sprang up in this period sought to affirm its new status in a traditional way, by commissioning portraits, so there was a ready and growing market. Portraiture was also one of the few genres that women could readily pursue. And a commissioned portrait enabled the artist to have a guaranteed sale, and a guaranteed price. Schwartze also had the personality and social skills to liaise well with often fussy clients. And to cap it off, she was very good at portraits.

For her, “an artist’s life was not a solitary struggle to express highly personal emotions; it was a business venture, and she paid careful attention to every aspect of efficient business management”. Furthermore, in her case, it was not only a business: it was a family business. So, “the other members of the family, who were financially dependent on her, were her most loyal assistants. They kept house, maintained contact with clients, kept records of commissions and the agreed prices, conducted correspondence and organised public relations” [10].

Artistic and financial success came remarkably quickly. By 1878, her work was being exhibited in several places in Amsterdam. Remarkably, from then on, until her death in 1918, “there was not a single year in which Schwartze did not exhibit” [11]. By 1879 she was submitting work to the prestigious Paris Salon exhibition, and continued to do so for the next twenty years.

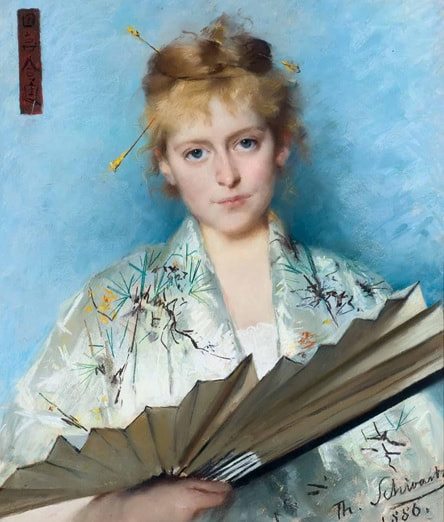

Constantly exhibiting, both in the Netherlands and – importantly – overseas, kept her name before the public, and helped her reputation grow. She capitalised on this by engaging with the news media, submitting articles on art and artistic life, organising self-portraits (such as Figs 2, 9) and publicity photographs of herself, often with brush in hand [12]. She also worked on fostering her relationships with the increasingly-influential art societies and exhibiting committees, and reinforced her international connections with extended stays in Paris, the centre of European art at the time. As time went by, she also won numerous prizes and obtained prestigious positions on exhibition juries.

From the outset, she determined to concentrate on portraits, the area in which she had received her training from her father. Portraiture had not been a major theme in Dutch art, but there were factors that made the time ripe for an artist of her talents [9]. It was an era of strong economic growth in the Netherlands, and a rising class of upper-middle class was emerging. The nouveau riche that sprang up in this period sought to affirm its new status in a traditional way, by commissioning portraits, so there was a ready and growing market. Portraiture was also one of the few genres that women could readily pursue. And a commissioned portrait enabled the artist to have a guaranteed sale, and a guaranteed price. Schwartze also had the personality and social skills to liaise well with often fussy clients. And to cap it off, she was very good at portraits.

For her, “an artist’s life was not a solitary struggle to express highly personal emotions; it was a business venture, and she paid careful attention to every aspect of efficient business management”. Furthermore, in her case, it was not only a business: it was a family business. So, “the other members of the family, who were financially dependent on her, were her most loyal assistants. They kept house, maintained contact with clients, kept records of commissions and the agreed prices, conducted correspondence and organised public relations” [10].

Artistic and financial success came remarkably quickly. By 1878, her work was being exhibited in several places in Amsterdam. Remarkably, from then on, until her death in 1918, “there was not a single year in which Schwartze did not exhibit” [11]. By 1879 she was submitting work to the prestigious Paris Salon exhibition, and continued to do so for the next twenty years.

Constantly exhibiting, both in the Netherlands and – importantly – overseas, kept her name before the public, and helped her reputation grow. She capitalised on this by engaging with the news media, submitting articles on art and artistic life, organising self-portraits (such as Figs 2, 9) and publicity photographs of herself, often with brush in hand [12]. She also worked on fostering her relationships with the increasingly-influential art societies and exhibiting committees, and reinforced her international connections with extended stays in Paris, the centre of European art at the time. As time went by, she also won numerous prizes and obtained prestigious positions on exhibition juries.

In all of her activities she was well-advised by the art conoisseur, critic and journalist Anton van Duyl, who took a deep and abiding interest in her career, advised her on artistic and market trends and, as editor-in-chief of a daily newspaper, helped her with networking and publicity. The two became lovers in 1880, though van Duyl was much older than her and was also married [13].

Schwartze also received considerable support and encouragement from Gijsbert van Tienhoven, the mayor of Amsterdam. He was instrumental in introducing her to the Dutch Royal Family, which led to a number of highly-prestigious royal commissions that “firmly established her position as the leading portraitist of the elite”. Prominently included in these were portraits of Wilhelmina, both as an 8-year-old princess, and on her inauguration as Queen ten years later (Figs 3 and 4).

Schwartze also received considerable support and encouragement from Gijsbert van Tienhoven, the mayor of Amsterdam. He was instrumental in introducing her to the Dutch Royal Family, which led to a number of highly-prestigious royal commissions that “firmly established her position as the leading portraitist of the elite”. Prominently included in these were portraits of Wilhelmina, both as an 8-year-old princess, and on her inauguration as Queen ten years later (Figs 3 and 4).

Working methods

It’s been estimated that, over her four-decade career, Schwartze produced about a thousand works. That means that she typically took only about one or two weeks to complete each commission, a truly prodigious output, especially considering their consistently high level of quality [14]. Even long after she had achieved the status of a millionaire (in 1885 alone it’s estimated that she made the present-day equivalent of about a quarter of a million dollars), she continued working with undiminished energy. Her workload demonstrated an almost obsessional commitment to her work, a poke-in-the-eye for her critics (of which more later) and a constant desire to maintain her hard-won success and reputation [15].

At the outset of her career, she had painted exclusively in oils, and her work featured a relatively dark palette, reminiscent of the works of her father and her Munich tutors. However, under influences from the emerging Impressionist painters, she later developed the use of much lighter colours, with more motion in the pose, and freer and more obvious brushwork. In addition, from the mid-1880s, and in accordance with advice from van Duyl, she started gravitating more and more to the more delicate pastels, particularly for portraying women and children. These also had the benefit of being quicker, lighter to transport, and requiring no drying time. As Hollema comments, “she had a genius for representing translucent tulle, frills, bows and other playful, elegant accessories of ladies and children’s garments with her pastels such that they appeared almost tangible” [16].

Pastels had not previously been widely used by Netherlands painters, but her pastel portrait of Princess Wilhelmina (Fig 3), in particular, triggered a sharp increase in its popularity. It also drove up pastel prices to the higher level that oil portraits could command [17].

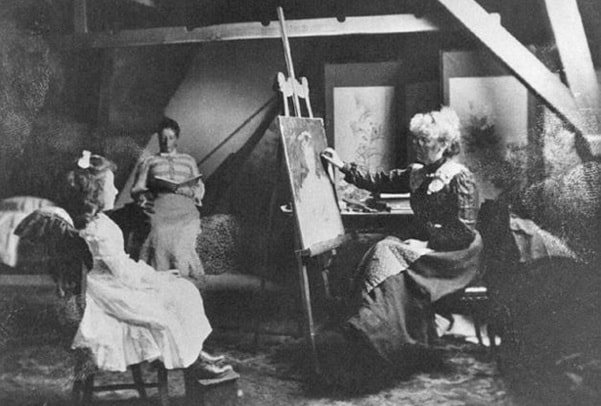

As befitting her status as a successful artist, her studio also included facilities for small exhibitions of her work, for receiving clients, and for hosting receptions. Attached to the family’s living quarters, they were designed to impress. When the occasion arose, however, she would also visit the sitter’s house. For example, in the case of her portrait of a young girl Maggie, daughter of a baron, the town mayor, the sittings took place over the course of a week in the attic of the mayor’s official residence (Fig 7).

As befitting her status as a successful artist, her studio also included facilities for small exhibitions of her work, for receiving clients, and for hosting receptions. Attached to the family’s living quarters, they were designed to impress. When the occasion arose, however, she would also visit the sitter’s house. For example, in the case of her portrait of a young girl Maggie, daughter of a baron, the town mayor, the sittings took place over the course of a week in the attic of the mayor’s official residence (Fig 7).

In this photograph, we can see Maggie’s mother in the background, reading aloud to her. Schwartze believed that this was important to alleviate the sitter’s boredom and help her maintain a lively expression [18]. A notation on the souvenir photograph of the sittings summed up the experience:

“Spent a week in the attic

Definitely not a joke!

As a souvenir for posterity

Maggie’s image is here”

The finished portrait itself is at Fig 8.

“Spent a week in the attic

Definitely not a joke!

As a souvenir for posterity

Maggie’s image is here”

The finished portrait itself is at Fig 8.

Schwartze was also not averse to using photographs to assist in her portraits, especially where the sitter was pressed for time, or in portraits of deceased persons [19]. These would preferably be professionally taken, and she would often use them compositionally, as a start point rather than as a rigid guide. In the case of Wilhelmina’s inauguration portrait (Fig 4), for example, she made a number of subtly flattering changes to the image of Wilhelmina in the photo that she used – a more dramatic colouring, a slimmer waist, an attenuated bare neck, a more compact bust, and so on.

Schwartze would also take care, in the case of her female sitters, to ensure that they were wearing appropriately flattering clothes that would present them in their best light. Her niece Lizzy Ansingh commented on her patient determination to make something interesting of even “difficult” cases. “She would take them off to fashion house Hirsch’s in Amsterdam and dress them entirely according to her own decorative taste, choosing the most delicate objects and the most flattering embellishments for them, and when they returned it was as if a radiant aura surrounded them” [20].

Schwartze would also take care, in the case of her female sitters, to ensure that they were wearing appropriately flattering clothes that would present them in their best light. Her niece Lizzy Ansingh commented on her patient determination to make something interesting of even “difficult” cases. “She would take them off to fashion house Hirsch’s in Amsterdam and dress them entirely according to her own decorative taste, choosing the most delicate objects and the most flattering embellishments for them, and when they returned it was as if a radiant aura surrounded them” [20].

Criticism and reviews

Over her lifetime, Schwartze probably attracted more admiration and more vilification than any other Dutch woman artist [21].

For many years she basked in the warmest praise, with her work being considered as entitling her to “a place of honour among our leading masters” [22]. She continued to collect prizes and prestigious royal commissions, was exhibited internationally, and was invited to contribute a portrait for the Uffizi Portrait Gallery (Fig 9).

For many years she basked in the warmest praise, with her work being considered as entitling her to “a place of honour among our leading masters” [22]. She continued to collect prizes and prestigious royal commissions, was exhibited internationally, and was invited to contribute a portrait for the Uffizi Portrait Gallery (Fig 9).

Yet no matter how favourable the reviews of her work were, there was often an undercurrent of condescension, particularly from male critics (as most critics were). This often took the form of extravagantly high praise, followed immediately by an expression of head-shaking amazement that such high-quality work could actually have been created by a mere woman. This attitude had long been the way in which male critics could explain away substantial achievements by women without admitting that those achievements challenged the assumed order of male superiority. So, a painting by a women could be described as fine but freakish, diminishing its importance in the general scheme of things [23]. Here for example, is an adulatory ode, written in her honour in 1881:

“How can that tender hand paint such fine traits

And in rich colours impact efforts so bold? [....]

Hail to this child of art, whose great inscrutable gift

Did not cut woman’s grace and heart adrift! [24].

At the same time, a woman artist’s success could be explained on the basis that she had succeeded precisely because she had adopted male attributes, which had enabled her to go beyond women’s “normal” puny abilities. So, for example, one critic of her work in 1880 marvelled that, “the merits of this picture do not derive solely from its remarkable, perfect likeness, but equally well …from the admirable treatment, which would certainly not lead one to suspect a woman’s hand” [25].

And this final part of a satirical poem about her in 1904:

“But let us stop joking and admit

This painting filly is fit!

With female love and male panache

She has turned all her art into cash” (italics added)

This attitude also had roots in the still-prevailing attitude that practising art as a career, especially a full-time career, was not a suitable choice for a woman in the first place. One commentator, writing in 1900, noted that, “It was thought unseemly for a young girl to be concerning herself with anything outside the home… Embroidery, darning, sewing, knitting and reading – all this was permissible, but painting and drawing as a career for a woman [and] the idea of acting independently in public to sell her work was unthinkable… It was, above all, the idea of offering one’s work for sale and receiving money for it, that would have provoked most indignation… To disavow feminine modesty to such an extent as to vie with men in the sphere of art and, like them to set a price on the work they submitted…no-one thought that such a day would ever dawn” [26].

Such views were not confined to men. Many women who themselves had been brought up in a male dominated society, in which independent thinking by women was discouraged, were not able or even willing to act in ways that fell outside the norm. Schwartze herself certainly did not lack ability or confidence but, even so, her male mentor felt it necessary to warn her that “A feminine lack of self-confidence will stand in your way, if you do not succeed in overcoming it” (which she certainly did). Another critic, giving her congratulations in 1889: “I think you acted boldly – like a man! – by doing what you did this winter” [27].

“How can that tender hand paint such fine traits

And in rich colours impact efforts so bold? [....]

Hail to this child of art, whose great inscrutable gift

Did not cut woman’s grace and heart adrift! [24].

At the same time, a woman artist’s success could be explained on the basis that she had succeeded precisely because she had adopted male attributes, which had enabled her to go beyond women’s “normal” puny abilities. So, for example, one critic of her work in 1880 marvelled that, “the merits of this picture do not derive solely from its remarkable, perfect likeness, but equally well …from the admirable treatment, which would certainly not lead one to suspect a woman’s hand” [25].

And this final part of a satirical poem about her in 1904:

“But let us stop joking and admit

This painting filly is fit!

With female love and male panache

She has turned all her art into cash” (italics added)

This attitude also had roots in the still-prevailing attitude that practising art as a career, especially a full-time career, was not a suitable choice for a woman in the first place. One commentator, writing in 1900, noted that, “It was thought unseemly for a young girl to be concerning herself with anything outside the home… Embroidery, darning, sewing, knitting and reading – all this was permissible, but painting and drawing as a career for a woman [and] the idea of acting independently in public to sell her work was unthinkable… It was, above all, the idea of offering one’s work for sale and receiving money for it, that would have provoked most indignation… To disavow feminine modesty to such an extent as to vie with men in the sphere of art and, like them to set a price on the work they submitted…no-one thought that such a day would ever dawn” [26].

Such views were not confined to men. Many women who themselves had been brought up in a male dominated society, in which independent thinking by women was discouraged, were not able or even willing to act in ways that fell outside the norm. Schwartze herself certainly did not lack ability or confidence but, even so, her male mentor felt it necessary to warn her that “A feminine lack of self-confidence will stand in your way, if you do not succeed in overcoming it” (which she certainly did). Another critic, giving her congratulations in 1889: “I think you acted boldly – like a man! – by doing what you did this winter” [27].

The criticism grows...

As early as the 1880s, unfavourable assessments of her work started to gain strength. Partly, these were motivated by envy and resentment that she had such eminent patrons, such a high public profile and such financial success. One critic, for example, concluded, “She may have something, but she’s also a queen of fashion, and wants to be …I can’t forgive her journalism and advertising” [28].

Other criticisms stemmed from the fact that so much of her subject matter was limited to portraits commissioned by the wealthy, resulting in a level of privilege and superficiality. This was exacerbated by the fact that fashions in art were changing. Increased emphasis was increasingly being placed on “real” life on the streets, on art that challenged old forms and addressed social concerns. Against this background, her work was starting to look conventional and privileged, and her style dated. Added to this, the emergence of the camera was increasingly taking the place of formal painted portraits.

So, there was a sense in which the modern world of art was starting to gain momentum, but without her on board. One critic complained that Schwartze had betrayed her talent, contenting herself with dashing off work that remained superficial and facile – “Every innovative thrust in art has passed her by…What a pity that she is not in sympathy with the great endeavour of this century and that she is not inspired by a strong desire to be, above all, simple and true!”. Another bitterly lamented, “That Miss Schwartze herself does not tire of immortalising all those rich kids in pastels passes my comprehension but, in any case, I would consider it very kind of her to stop needlessly boring others with them at every exhibition” [29].

Other criticisms stemmed from the fact that so much of her subject matter was limited to portraits commissioned by the wealthy, resulting in a level of privilege and superficiality. This was exacerbated by the fact that fashions in art were changing. Increased emphasis was increasingly being placed on “real” life on the streets, on art that challenged old forms and addressed social concerns. Against this background, her work was starting to look conventional and privileged, and her style dated. Added to this, the emergence of the camera was increasingly taking the place of formal painted portraits.

So, there was a sense in which the modern world of art was starting to gain momentum, but without her on board. One critic complained that Schwartze had betrayed her talent, contenting herself with dashing off work that remained superficial and facile – “Every innovative thrust in art has passed her by…What a pity that she is not in sympathy with the great endeavour of this century and that she is not inspired by a strong desire to be, above all, simple and true!”. Another bitterly lamented, “That Miss Schwartze herself does not tire of immortalising all those rich kids in pastels passes my comprehension but, in any case, I would consider it very kind of her to stop needlessly boring others with them at every exhibition” [29].

Marriage and later career

When Schwartze was 55, she finally married Van Duyl [30]. They were a blissfully devoted couple, and she admired him intensely. She continued to work assiduously and, despite the growing criticism of her work, her career continued to prosper among her conservative clientele [31].

However, from 1910 onwards the prices she could ask for her commissions started dropping – an ominous development, and one that she was keen should not become publicly known. On top of this, Van Duyl’s death in 1918 left her bereft, and seemed to break her spirit. Just five months later, she also died, possibly of complications arising from the Spanish Flu pandemic.

Her funeral attracted enormous public interest [32], with huge crowds lining the canals to watch the funeral procession and hundreds more attending the funeral service. Her impressive tomb, seen here, was designed by her sister Georgine and may be found today in Amerdam’s Oosterbegraafplaats Cemetery. It has since been declared a national monument by the Dutch government.

Her funeral attracted enormous public interest [32], with huge crowds lining the canals to watch the funeral procession and hundreds more attending the funeral service. Her impressive tomb, seen here, was designed by her sister Georgine and may be found today in Amerdam’s Oosterbegraafplaats Cemetery. It has since been declared a national monument by the Dutch government.

A decline in reputation, and a revival

After her death, with no more new works appearing, and the adverse critics’ viewpoints having now permeated into mainstream thinking, her public reputation started to rapidly wither away. This process was accelerated by the fact that most of her works, being privately commissioned, were held in private collections, not on public view in museums or galleries. Her painter niece Lizzy Ansingh, who had been trained and mentored by Schwartze, tried to keep the memory alive with a memorial exhibition, which received mixed reviews; and set up a memorial foundation, which continues to this day to award promising portraitists. Members of Lizzy’s female Amsterdam Joffers painting group also praised her as “one of the greatest women portrait painters of our century” [33]. But an early biography published shortly after her death was lukewarm about her future legacy, simply concluding that she was “a personality who will not be forgotten” [34]; and another critic simply summed her up as a “unique figure” with “a distinctive point of view” [35].

In this context, some useful parallels can be drawn with the career of the American artist John Singer Sargent, an almost exact contemporary of Schwartze. Like her, he had prospered by being able to rapidly produce very high-quality society portraits, and his reputation also declined rapidly in the 20th century for similar reasons. However, his reputation subsequently revived, due to a number of factors that did not apply to Schwartze – Sargent had eventually stopped doing portraits (which he had begun to hate, saying "I abhor and abjure them and hope never to do another especially of the Upper Classes" [36]; furthermore, he had a wider range, and could work with great skill in various media such as watercolours. Importantly, too, in the course of acting as an official war artist, he was able to produce an acknowledged war masterpiece [37].

In Schwartze’s case, after many decades of neglect in the public eye, there has been a belated revival of interest, though on a limited scale. This recent new interest in her is due largely to the efforts of art scholar Cora Hollema, who came across Schwartze in the 1970s and has recently produced a definitive account of her life and works [38]. As a result, Schwartze has become increasingly recognised and included in a number of exhibitions in recent years, and two of her paintings have been placed on permanent view at the Rijksmuseum.

In this context, some useful parallels can be drawn with the career of the American artist John Singer Sargent, an almost exact contemporary of Schwartze. Like her, he had prospered by being able to rapidly produce very high-quality society portraits, and his reputation also declined rapidly in the 20th century for similar reasons. However, his reputation subsequently revived, due to a number of factors that did not apply to Schwartze – Sargent had eventually stopped doing portraits (which he had begun to hate, saying "I abhor and abjure them and hope never to do another especially of the Upper Classes" [36]; furthermore, he had a wider range, and could work with great skill in various media such as watercolours. Importantly, too, in the course of acting as an official war artist, he was able to produce an acknowledged war masterpiece [37].

In Schwartze’s case, after many decades of neglect in the public eye, there has been a belated revival of interest, though on a limited scale. This recent new interest in her is due largely to the efforts of art scholar Cora Hollema, who came across Schwartze in the 1970s and has recently produced a definitive account of her life and works [38]. As a result, Schwartze has become increasingly recognised and included in a number of exhibitions in recent years, and two of her paintings have been placed on permanent view at the Rijksmuseum.

Conclusion

Earlier we’ve looked at some of the particular difficulties that women have faced over the centuries in making successful and financially rewarding careers as artists. Schwartze was able to overcome many of these, partly because of her talent as an artist, but also as a result of a happy combination of factors such as her early training, lifelong commitment and drive, expert guidance and mentorship from influential advisers, incredible capacity for work, professional turn of mind and assiduous attention to publicity and reputation.

In doing so, as Hollema points out, Schwartze was following a tradition set by highly-talented successful women court painters, such as the 18th century artists Angelica Kauffmann and Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun. There are many interesting parallels in the careers of all three women. All came from artists’ families and were initially taught, at an early age, by their fathers or other male relatives, usually with a view to becoming able to earn money and support a family. They were all early blossomers, and were channelled into portraiture -- one of the limited number of genres readily available to women and where there was a ready market. It helped that they were reasonably attractive, and were able to establish rapport with their sitters. Once having established a good reputation with upper middle-class sitters, they eventually started receiving royal commissions, which in turn made their works highly prized [39].

This, of course, is a rather limited pathway to success, particularly in the more modern era. Not everyone nowadays sees the pinnacle as getting commissions for royal portraits. But even in Schwartze’s time there were the stirrings of change, a widening of possibilities for women. Agitation for causes such as women’s suffrage was increasing and, although she did not publicly endorse the aims of the suffragettes (particularly the more scruffy ones), she freely lent her time and expertise to committees organising women’s art exhibitions [40].

In the 1880s women Impressionists such as Mary Cassatt and Berth Morisot, along with proponents of the proto-feminist New Woman movement, such as Cecelia Beaux, were making names for themselves as serious artists. And while Schwartze’s style of art may have been outmoded by the time she died, she herself, with her extraordinary work ethic and financial success, also provided a valuable role model in subverting the usual expectations.

© Philip McCouat, 2022. First published January 2022

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Forgotten Women Artists #5: Thérèse Schwartze and the business of painting”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. For other articles in this series, see:

Forgotten Women Artists #1: Arcangela Paladini: The Rapid Rise and Fall of a Prodigy

Forgotten Women Artists #3: Marie-Gabrielle Capet: Stepping Out from the Shadows

Forgotten Women Artists #2: Jane Loudon: Artist, Futurist, Horticulturist and Author

Forgotten Women Artists #4: Michaelina Wautier: entering the limelight after 300 years

RETURN TO HOME

In doing so, as Hollema points out, Schwartze was following a tradition set by highly-talented successful women court painters, such as the 18th century artists Angelica Kauffmann and Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun. There are many interesting parallels in the careers of all three women. All came from artists’ families and were initially taught, at an early age, by their fathers or other male relatives, usually with a view to becoming able to earn money and support a family. They were all early blossomers, and were channelled into portraiture -- one of the limited number of genres readily available to women and where there was a ready market. It helped that they were reasonably attractive, and were able to establish rapport with their sitters. Once having established a good reputation with upper middle-class sitters, they eventually started receiving royal commissions, which in turn made their works highly prized [39].

This, of course, is a rather limited pathway to success, particularly in the more modern era. Not everyone nowadays sees the pinnacle as getting commissions for royal portraits. But even in Schwartze’s time there were the stirrings of change, a widening of possibilities for women. Agitation for causes such as women’s suffrage was increasing and, although she did not publicly endorse the aims of the suffragettes (particularly the more scruffy ones), she freely lent her time and expertise to committees organising women’s art exhibitions [40].

In the 1880s women Impressionists such as Mary Cassatt and Berth Morisot, along with proponents of the proto-feminist New Woman movement, such as Cecelia Beaux, were making names for themselves as serious artists. And while Schwartze’s style of art may have been outmoded by the time she died, she herself, with her extraordinary work ethic and financial success, also provided a valuable role model in subverting the usual expectations.

© Philip McCouat, 2022. First published January 2022

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Forgotten Women Artists #5: Thérèse Schwartze and the business of painting”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. For other articles in this series, see:

Forgotten Women Artists #1: Arcangela Paladini: The Rapid Rise and Fall of a Prodigy

Forgotten Women Artists #3: Marie-Gabrielle Capet: Stepping Out from the Shadows

Forgotten Women Artists #2: Jane Loudon: Artist, Futurist, Horticulturist and Author

Forgotten Women Artists #4: Michaelina Wautier: entering the limelight after 300 years

RETURN TO HOME

End notes

1. In the preparation of this article, I have relied heavily on the definitive work on Schwartze by Cora Hollema & Pieternel Kouwenhoven,Thérèse Schwartze: painting for a living, (transl Beverley Jackson), Amsterdam, 2nd edn, 2021.

(order through www.thereseschwartze.com). For our review of this book, see here.

2. Hollema et al, op cit at 8

3. He would later become the honorary consul of North America from 1851-6

4. Hollema et al, op cit at 12-13

5. Hollema et al, op cit at 6

6. Hollema et al, op cit at 20

7, From Franz von Lenbach and Gabriel Max; Hollema et al, op cit at 15

8. Hollema et al, op cit at 32

9. Hollema et al, op cit at 71

10. Hollema et al, op cit at 32

11. Hollema et al, op cit at 34

12. Hollema et al, op cit at 35

13. Hollema et al, op cit at 34

14. Hollema et al, op cit at 70

15. It is interesting that when T was asked to submit a self-portrait to the Uffizi, her painting (Fig 9) echoed the 1748 self-portrait of Joshua Reynolds who, like T, was a portraitist with royal connections who worked very long hours

16. Hollema et al, op cit at 73

17. Oil paintings were more durable, less sensitive to moisture and stereotypically perceived as more “masculine”: Hollema et al, op cit at 42

18. Hollema et al, op cit at 100

19. Hollema et al, op cit at 72

20. Hollema et al, op cit at 73

21. Hollema et al, op cit at 144

22. Hollema et al, op cit at 144

23. Germaine Greer, The Obstacle Race: The fortunes of women painters and their work, Pan Books, London, 1981 at 4

24. Hollema et al, op cit at 144. Italics added

25. Hollema et al, op cit at 144. Italics added

26. Hollema et al. op cit at 8-9

27. Hollema et al, op cit at 26, 147

28. Hollema et al, op cit at 145

29. Hollema et al, op cit at 145, 146

30. This occurred after his first wife died

31. Hollema et al, op cit at 147ff

32. Hollema et al, op cit at 40

33. Hollema et al, op cit at 181

34. Willem Martin, Thérèse van Duyl-Schwartze (1851-1918), Amsterdam 1923

35. Hollema et al, op cit at 183

36. Stanley Olson, John Singer Sargent: His Portrait, London, 1986, at 237

37. The painting was Gassed (1919; for further details see our article on Singer’s muse http://www.artinsociety.com/rose-marie-ormond-sargentrsquos-muse-and-ldquothe-most-charming-girl-that-ever-livedrdquo.html

38. Hollema et al, op cit

39. Hollema et al, op cit at 180

40. Hollema et al, op cit at 180

© Philip McCouat 2022. First published January 2022

RETURN TO HOME

(order through www.thereseschwartze.com). For our review of this book, see here.

2. Hollema et al, op cit at 8

3. He would later become the honorary consul of North America from 1851-6

4. Hollema et al, op cit at 12-13

5. Hollema et al, op cit at 6

6. Hollema et al, op cit at 20

7, From Franz von Lenbach and Gabriel Max; Hollema et al, op cit at 15

8. Hollema et al, op cit at 32

9. Hollema et al, op cit at 71

10. Hollema et al, op cit at 32

11. Hollema et al, op cit at 34

12. Hollema et al, op cit at 35

13. Hollema et al, op cit at 34

14. Hollema et al, op cit at 70

15. It is interesting that when T was asked to submit a self-portrait to the Uffizi, her painting (Fig 9) echoed the 1748 self-portrait of Joshua Reynolds who, like T, was a portraitist with royal connections who worked very long hours

16. Hollema et al, op cit at 73

17. Oil paintings were more durable, less sensitive to moisture and stereotypically perceived as more “masculine”: Hollema et al, op cit at 42

18. Hollema et al, op cit at 100

19. Hollema et al, op cit at 72

20. Hollema et al, op cit at 73

21. Hollema et al, op cit at 144

22. Hollema et al, op cit at 144

23. Germaine Greer, The Obstacle Race: The fortunes of women painters and their work, Pan Books, London, 1981 at 4

24. Hollema et al, op cit at 144. Italics added

25. Hollema et al, op cit at 144. Italics added

26. Hollema et al. op cit at 8-9

27. Hollema et al, op cit at 26, 147

28. Hollema et al, op cit at 145

29. Hollema et al, op cit at 145, 146

30. This occurred after his first wife died

31. Hollema et al, op cit at 147ff

32. Hollema et al, op cit at 40

33. Hollema et al, op cit at 181

34. Willem Martin, Thérèse van Duyl-Schwartze (1851-1918), Amsterdam 1923

35. Hollema et al, op cit at 183

36. Stanley Olson, John Singer Sargent: His Portrait, London, 1986, at 237

37. The painting was Gassed (1919; for further details see our article on Singer’s muse http://www.artinsociety.com/rose-marie-ormond-sargentrsquos-muse-and-ldquothe-most-charming-girl-that-ever-livedrdquo.html

38. Hollema et al, op cit

39. Hollema et al, op cit at 180

40. Hollema et al, op cit at 180

© Philip McCouat 2022. First published January 2022

RETURN TO HOME