THE CONTROVERSIES OF CONSTANTIN BRANCUSI

PRINCESS X AND THE BOUNDARIES OF ART

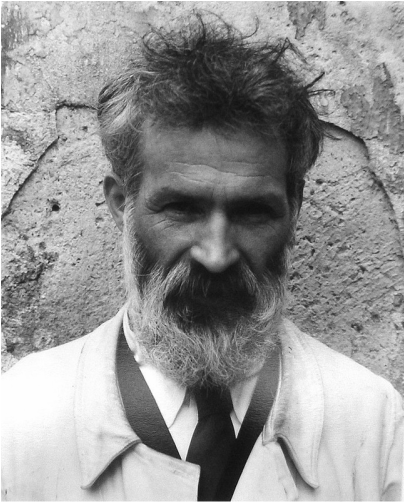

Constantin Brancusi, a Romanian who lived in France, is now regarded as one of the most influential sculptors of the 20th century [1]. He made his name by rejecting traditional views of sculpture. Instead, he favoured simplified, stylised, curved works which expressed, or at least suggested, ideals or non-concrete concepts. According to Brancusi, the “abstract” was itself a reality, and what was important was to show the essence of things, rather than their outer form. In his view, "the decline of sculpture started with Michelangelo… How could a person sleep in a room next to his Moses? Michelangelo's sculpture is nothing but muscle, beefsteak… beefsteak run amok."[2]. It was an approach which would inevitably attract both extravagant praise and extravagant criticism.

In this article we look at two scandals which particularly brought Brancusi’s name and his work to the public eye. The first involved elements guaranteed to arouse popular interest – a mystery woman and a bitter row over whether Brancusi’s depiction of her was obscene. The second, potentially more serious, called into question whether Brancusi’s sculpture qualified as art at all. Both disputes, in their own way, would play a role in helping to define the boundaries of art.

PART 1

Princess X: the essence of woman, or just lewd?

On 28 January 1920 Brancusi exhibited one his works, rather coyly titled Princess X, at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris (Fig 2) [3]. The work features a slightly inclined ovoid head and a long neck terminating in a full bust. Tiny ripples at the junction of the head and neck denote the hair.

|

The work had been shown before, at the Society of Independent Artists in New York, without significant incident (In fact, it had been completely eclipsed there by the sensation surrounding the urinal in Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain) [4]. But in Paris, it happened that one very famous visitor – accounts differ as to whether it was Picasso or Matisse – drew attention to it by exclaiming, “Here it is: the phallus!”

The comment evidently struck a chord; it is true that from many angles the work takes on a noticeably phallic appearance. With the French Minister just about to have an escorted walk through the exhibition, the embarrassed organisers forced Brancusi to withdraw the sculpture on the ground that it was “liable to cause incidents”. One apparently expostulated that “you could not march the Minister past a pair of balls” [5]. |

The matter quickly became a cause célébre. For Brancusi, the rejection and subsequent public furore made him feel “like someone who’s been knocked senseless in the dark”[6]. He stated the rationale of the sculpture in a newspaper interview:

“My statue is of woman, all women rolled into one, Goethe’s Eternal Feminine reduced to its essence … For five years I worked, I simplified, I made the material speak out and state the inexpressible. For indeed, what exactly is a woman? Buttons and bows, with a smile on her lips and paint on her cheeks…That’s not woman. To express that entity, to bring back to the world of the senses that eternal type of ephemeral forms, I spent five years simplifying, honing my work. And at last I have, I believe, emerged triumphant and transcended the material. Besides, it is such a pity to spoil a beautiful by digging out little holes for hair, eyes, ears. And my material is so beautiful, with its sinuous lines that shine like pure gold and sum up in a single archetype all the female effigies on Earth.” [7]

Later he would put it this way:

“A nose doesn’t make you, nor are your ears a part of the essence of you… I look at what is real to me. We are all alike. We have one nose, two ears, two eyes, but in architectural shape we are different. A thing which would pretend to reproduce nature would only be a copy. I am trying to get a spiritual effect. If you put an ear there it would be in the way.” [8]

Clearly, it would have been dispiriting for Brancusi to labour for five years in creating the essence of womanhood, only to end up with something that many felt looked more like a phallus. But were Brancusi’s motivations so pure? For this we need to delve back into the origins of the work -- and to the identity of the sitter.

“My statue is of woman, all women rolled into one, Goethe’s Eternal Feminine reduced to its essence … For five years I worked, I simplified, I made the material speak out and state the inexpressible. For indeed, what exactly is a woman? Buttons and bows, with a smile on her lips and paint on her cheeks…That’s not woman. To express that entity, to bring back to the world of the senses that eternal type of ephemeral forms, I spent five years simplifying, honing my work. And at last I have, I believe, emerged triumphant and transcended the material. Besides, it is such a pity to spoil a beautiful by digging out little holes for hair, eyes, ears. And my material is so beautiful, with its sinuous lines that shine like pure gold and sum up in a single archetype all the female effigies on Earth.” [7]

Later he would put it this way:

“A nose doesn’t make you, nor are your ears a part of the essence of you… I look at what is real to me. We are all alike. We have one nose, two ears, two eyes, but in architectural shape we are different. A thing which would pretend to reproduce nature would only be a copy. I am trying to get a spiritual effect. If you put an ear there it would be in the way.” [8]

Clearly, it would have been dispiriting for Brancusi to labour for five years in creating the essence of womanhood, only to end up with something that many felt looked more like a phallus. But were Brancusi’s motivations so pure? For this we need to delve back into the origins of the work -- and to the identity of the sitter.

The extraordinary Marie Bonaparte

Back in about 1909, Brancusi had been asked by “a lady from Paris, a princess” to carve a bust of her. He demurred – he had a “horror and miserably low opinion” of bust sculpture. But the princess was not to be put off, he said, and “coquettishly asked me to make an exception”. Brancusi reconsidered: “she had a beautiful bust, but ugly legs and was terribly vain. She was looking in the mirror all the time, even during lunch… discreetly placing the mirror on the table, looking furtive. She was vain and sensual”[9].

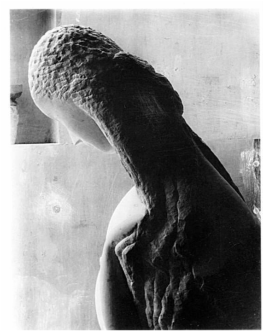

The upshot was that he created a sculpture called Woman Looking in a Mirror (Fig 3), depicting the princess’ head as being bent to catch her reflection [10]. It seems that it was this sculpture, later destroyed, that Brancusi spent his five years simplifying into Princess X, with the role of the mirror being recalled by the new work's highly reflective bronze surface.

The upshot was that he created a sculpture called Woman Looking in a Mirror (Fig 3), depicting the princess’ head as being bent to catch her reflection [10]. It seems that it was this sculpture, later destroyed, that Brancusi spent his five years simplifying into Princess X, with the role of the mirror being recalled by the new work's highly reflective bronze surface.

Fig 3: Constantin Brancusi, Woman Looking in a Mirror (1909) Fig 3: Constantin Brancusi, Woman Looking in a Mirror (1909)

|

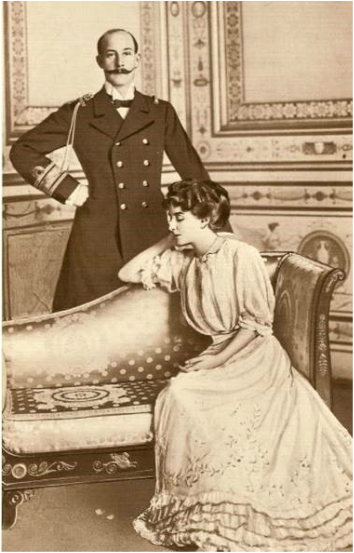

The sitter was actually Princess Marie Bonaparte [11]. She was the great grand-niece of Napoleon, and would be the aunt of both Princess Marina (the Duchess of Kent) and Prince Philip (the Duke of Edinburgh). Her family was enormously wealthy – her grandfather owned a large part of Monaco.

Marie would go on to achieve considerable fame, particularly in France, for her wide range of interests and achievements -- as a prime mover and practitioner in the psychoanalytic movement in France; a pioneer sex researcher; translator and author of multiple books ranging from a massive biography of Edgar Allen Poe (1949) to a story about her dog Topsy; and for using her wealth to enable more than 200 Jews (including Freud) to flee from the Nazis. |

However, without seeking to minimise these achievements, it was her own sexuality which is of most relevance for present purposes [12]. As a child, Marie was highly intelligent, but familial isolation and overprotection had left her rather prone to obsessional attachments. She had become interested in sex relatively early, but discovered that she herself was “frigid”, in the sense that she was unable to achieve sexual fulfilment through conventional intercourse. It was a quest that she would pursue vigorously, but unsuccessfully, for many years. Her 1907 marriage to Prince George of Greece did not help matters, as he himself favoured men. On their wedding night, Marie would later recall, he apologised to her, saying, “I hate it as much as you do. But we must do it if we want children.” [13]

Over time, Marie had a variety of lovers, including Aristide Briand, Premier of France, but her self-perceived lack of an appropriate sexual response became a major preoccupation for her. In 1924 she published an article Considerations on the Anatomical Causes of Frigidity in Women [14], in which she concluded that one cause of frigidity – the one which she herself believed that she suffered – was related to the distance between a woman’s clitoris and her vagina. Based on measurements carried out on a large number of women, she argued that those with short distances (the “paraclitoridiennes’) achieved orgasm easily during intercourse, while women with longer distances (the "téleclitoridiennes") did not.

In accordance with the theory, Marie later took the extreme step of undergoing multiple surgical attempts to “correct” her own genitalia, but these all proved ineffective [15]. She also underwent intense psychoanalysis with Sigmund Freud, who considered that she had bisexual tendencies [16]. Although Freud’s therapy also proved to be unsuccessful in solving her physical problem, it did succeed in giving Marie more peace of mind.

In accordance with the theory, Marie later took the extreme step of undergoing multiple surgical attempts to “correct” her own genitalia, but these all proved ineffective [15]. She also underwent intense psychoanalysis with Sigmund Freud, who considered that she had bisexual tendencies [16]. Although Freud’s therapy also proved to be unsuccessful in solving her physical problem, it did succeed in giving Marie more peace of mind.

Brancusi and his representation of women

Is it just a coincidence that this sensual, conflicted and dynamic woman, whom Brancusi met just two years after her marriage, was the model for a sculpture that many later saw as representing a phallus, or even an extreme expression of sexual duality? Was Brancusi really trying to express the essence of woman, as he said, or at some level was he expressing his view of Marie and her particular sexual personality? Brancusi himself later appeared to admit this possibility, writing that although he did not intend to model “the embodiment of [Marie’s] hidden desires”, he wondered if “this phenomenon” might have “happened unconsciously”[17]. It is interesting, too, that of the many photographs that Brancusi took of the work, almost all are from the angle in which the phallic shape is most noticeable [18].

A related issue also arises with Brancusi’s other works involving identified women. According to Sanda Miller:

“Eileen Lane, a glamorous Irish-American with whom Brancusi had a baffling relationship, refused to recognise herself in the upright egg... topped by a comical protuberance. Eugène Mayer became an erect phallus… Nancy Cunard was portrayed as upright half-ovoid resting on one leg and topped by a twisted curlicue, perhaps suggestive of her notoriously precarious life… Perhaps the most interesting is the wooden totem with a pan and topped by a tuft, a work purporting to be the beautiful Leonie Ricou [19]. Miller concludes that “we can certainly detect irony in Brancusi's ability to emphasise the foibles or less attractive character-traits of his sitters” [20].

Given this, Brancusi’s passionately stated claim that in Princess X he was expressing some ethereal “essence of woman” seems to be setting the bar rather too high. Indeed, the fact that the work has produced such wildly different interpretations requires us to ask whether it makes much sense to talk about this concept at all. Is there really an essence of woman? Wouldn’t a man’s concept of such an essence differ from that of a woman? And must it involve “beauty”, as Brancusi seemed to suggest in his newspaper interview? [21].

It seems more likely that in these works Brancusi was to some extent in fact expressing some view about the sitters themselves, rather than women in general. But, of course, we may never know the truth of the matter, and it might even be that Brancusi was not fully aware himself. Perhaps, in the end, one must be satisfied to simply view Princess X on its own terms, accepting Brancusi’s quintessentially modernist statement that he was portraying what was “real to me”, and remembering his advice to those seeking to interpret his works: “'Look at my sculptures until you see them.”

A related issue also arises with Brancusi’s other works involving identified women. According to Sanda Miller:

“Eileen Lane, a glamorous Irish-American with whom Brancusi had a baffling relationship, refused to recognise herself in the upright egg... topped by a comical protuberance. Eugène Mayer became an erect phallus… Nancy Cunard was portrayed as upright half-ovoid resting on one leg and topped by a twisted curlicue, perhaps suggestive of her notoriously precarious life… Perhaps the most interesting is the wooden totem with a pan and topped by a tuft, a work purporting to be the beautiful Leonie Ricou [19]. Miller concludes that “we can certainly detect irony in Brancusi's ability to emphasise the foibles or less attractive character-traits of his sitters” [20].

Given this, Brancusi’s passionately stated claim that in Princess X he was expressing some ethereal “essence of woman” seems to be setting the bar rather too high. Indeed, the fact that the work has produced such wildly different interpretations requires us to ask whether it makes much sense to talk about this concept at all. Is there really an essence of woman? Wouldn’t a man’s concept of such an essence differ from that of a woman? And must it involve “beauty”, as Brancusi seemed to suggest in his newspaper interview? [21].

It seems more likely that in these works Brancusi was to some extent in fact expressing some view about the sitters themselves, rather than women in general. But, of course, we may never know the truth of the matter, and it might even be that Brancusi was not fully aware himself. Perhaps, in the end, one must be satisfied to simply view Princess X on its own terms, accepting Brancusi’s quintessentially modernist statement that he was portraying what was “real to me”, and remembering his advice to those seeking to interpret his works: “'Look at my sculptures until you see them.”

PART 2

Bird in space, and in court

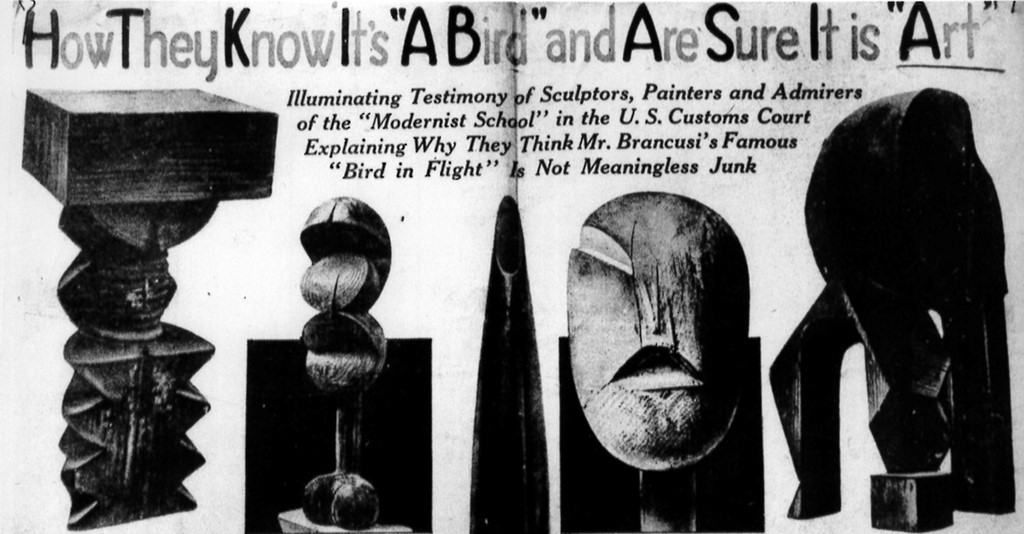

Six years later, Brancusi would be embroiled in an even more vexatious situation, arising out of the import of one of his works into New York A Customs appraiser, F J H Kracke, was presented with an unusual, highly polished object made of bronze, whose status had earlier been questioned by customs officials. After consultation, Kracke classified it as a “manufactured implement” and imposed the normal 40% customs duty applicable to metallic household utensils. He was probably unaware that his decision would lead to one of the more celebrated court cases in art history.

|

The object in question – a towering nine feet high including base, and titled Bird in Space (Fig 5) – had been created by Brancusi as one of a series of similarly-themed works [22]. Brancusi claimed that the work qualified for an exemption from duty on the ground that it qualified as a “professional production of a sculptor” which was an “original” and was not an “article of utility”, as set out in the Tariff Act 1922, para 1704. Kracke, on the other hand, relied on the opinions of “several men, high in the art world”; typical among these was one who stated, “if that’s art, hereafter I’m a bricklayer.” In general their opinion was that Brancusi’s work “left too much to the imagination” [23].

For Brancusi, this situation would have been even more infuriating than the Princess X incident. While that had involved controversy over the correction interpretation of his art, this new issue went to the fundamental question of whether his work qualified as art at all. |

In bringing an action in the United States Customs Court for recovery of the duty [24], Brancusi had to challenge a dictionary definition of a “work of art” that had been adopted by the courts ten years before. In that case, known as Olivotti, the court had ruled that:

“Sculpture is that branch of the free fine arts which chisels or carves in stone or other solid material or models in clay or other plastic substance for subsequent reproduction by carving or casting, imitations of natural objects, chiefly the human form, and represents such objects in their true proportions of length, breadth and thickness, or of length and breadth only” [25].

This definition, reflecting the traditional view that a work of art must be realistic and representational, was clearly too restrictive to cover Brancusi’s work. In fact, despite its title, Bird in Space lacked any of the attributes of a bird – bill, claws, feathers or even wings.

“Sculpture is that branch of the free fine arts which chisels or carves in stone or other solid material or models in clay or other plastic substance for subsequent reproduction by carving or casting, imitations of natural objects, chiefly the human form, and represents such objects in their true proportions of length, breadth and thickness, or of length and breadth only” [25].

This definition, reflecting the traditional view that a work of art must be realistic and representational, was clearly too restrictive to cover Brancusi’s work. In fact, despite its title, Bird in Space lacked any of the attributes of a bird – bill, claws, feathers or even wings.

Argument and counter-argument

The resultant case would be played out in the full glare of publicity, with passionate views being expressed both for and against [26].

It was clear that the work was not representational in the traditional sense of accurately depicting some natural object. Edward Steichen, an established photographer who had originally purchased the work for import, was questioned along these lines:

It was clear that the work was not representational in the traditional sense of accurately depicting some natural object. Edward Steichen, an established photographer who had originally purchased the work for import, was questioned along these lines:

Judge: What makes you call it a bird, does it look like a bird to you?

Steichen: It does not look like a bird, but I feel it is a bird, it is characterised by the artist as a bird.

Judge: If you saw it in the forest, you would not take a shot at it?

Steichen: No, your Honor.

Another of Brancusi’s witnesses, the sculptor Jacob Epstein, was asked:

Govt attorney: So if we had a brass rail, highly polished, curved in more or less harmonious circles, it would be a work of art?

Epstein : It might become a work of art.

Govt attorney: Whether it is made by a sculptor or made by a mechanic?

Epstein: A mechanic cannot make beautiful work. He could polish it up but he cannot conceive of the object.

The art critic Frank Crowninshield [27] perhaps articulated the issue best. Asked by the court what it was about the object which would lead him to believe it was a bird, he responded: “It has the suggestion of flight, it suggests grace, aspiration, vigour, coupled with speed in the spirit of strength, potency, beauty, just as a bird does. But just the name, the title, of this work, why, really, it does not mean much.”

The various arguments put forward by Brancusi’s witnesses could be summarised this way:

(1) the notion of aesthetic quality was a relative one -- reasonable men could disagree on it. The mere fact that eminent men on the government side did not consider it a work of art could not determine the matter

(2) it was possible for an artwork to represent an abstract concept – in this case, flight – without necessarily representing any particular object

(3) the work had “beauty“ in its own right, and this was also a relative standard

(4) it should not be a matter for the government to take sides for or against any school of art, whether known as realistic, impressionistic or abstract.

All this might well be so, but didn’t its non-objective representational nature still disqualify the work under the earlier precedent in Olivotti? Ultimately, the court rejected that argument and ruled in Brancusi’s favour. It concluded that since 1916, when the previous rule had been established, a new school of art had come into existence "whose exponents attempt to portray abstract ideas rather than to imitate natural objects. Whether or not we are in sympathy with these newer ideas and the schools which represent them, we think the fact of their existence and their influence upon the art world as recognized by the courts must be considered."

The court concluded that the Bird “is beautiful and symmetrical in outline, and while difficulty might be encountered in associating it with a bird, it is nevertheless pleasing to look at and highly ornamental". Consequently, it qualified for free entry as a work of art.

While this settled the case [28], it hardly settled the perennial issue of what constitutes art – a question that has become increasingly characterised by subjectivity and much throwing up of hands [29]. Although the court rejected the idea that realistic representation was a requirement of art, its emphasis on “beauty” and “symmetry” [30] was still highly restrictive, and far from the more modern conception of an artwork as an independently created, new self-contained reality which engages the viewer in some way.

Furthermore, as Giry has pointed out:

“It took years for customs law to shed other unreasonable limitations on the free import of artwork. In 1931, tapestries were deemed dutiable because they were made of wool—the material determined the artistic merit. In 1971, the customs court found that six carved door panels destined for a church were dutiable because, as part of the doors, they were utilitarian objects. It wasn't for 61 years, until the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of 1989, that customs law allowed free entry to works that are both artistic and functional”[31].

Just where the line needs to be drawn, or even whether it needs to be drawn at all, is still a live issue today. One truth, however, remains constant – that whenever governments take partisan sides on issues such as these, they are liable to make fools of themselves.

The various arguments put forward by Brancusi’s witnesses could be summarised this way:

(1) the notion of aesthetic quality was a relative one -- reasonable men could disagree on it. The mere fact that eminent men on the government side did not consider it a work of art could not determine the matter

(2) it was possible for an artwork to represent an abstract concept – in this case, flight – without necessarily representing any particular object

(3) the work had “beauty“ in its own right, and this was also a relative standard

(4) it should not be a matter for the government to take sides for or against any school of art, whether known as realistic, impressionistic or abstract.

All this might well be so, but didn’t its non-objective representational nature still disqualify the work under the earlier precedent in Olivotti? Ultimately, the court rejected that argument and ruled in Brancusi’s favour. It concluded that since 1916, when the previous rule had been established, a new school of art had come into existence "whose exponents attempt to portray abstract ideas rather than to imitate natural objects. Whether or not we are in sympathy with these newer ideas and the schools which represent them, we think the fact of their existence and their influence upon the art world as recognized by the courts must be considered."

The court concluded that the Bird “is beautiful and symmetrical in outline, and while difficulty might be encountered in associating it with a bird, it is nevertheless pleasing to look at and highly ornamental". Consequently, it qualified for free entry as a work of art.

While this settled the case [28], it hardly settled the perennial issue of what constitutes art – a question that has become increasingly characterised by subjectivity and much throwing up of hands [29]. Although the court rejected the idea that realistic representation was a requirement of art, its emphasis on “beauty” and “symmetry” [30] was still highly restrictive, and far from the more modern conception of an artwork as an independently created, new self-contained reality which engages the viewer in some way.

Furthermore, as Giry has pointed out:

“It took years for customs law to shed other unreasonable limitations on the free import of artwork. In 1931, tapestries were deemed dutiable because they were made of wool—the material determined the artistic merit. In 1971, the customs court found that six carved door panels destined for a church were dutiable because, as part of the doors, they were utilitarian objects. It wasn't for 61 years, until the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of 1989, that customs law allowed free entry to works that are both artistic and functional”[31].

Just where the line needs to be drawn, or even whether it needs to be drawn at all, is still a live issue today. One truth, however, remains constant – that whenever governments take partisan sides on issues such as these, they are liable to make fools of themselves.

conclusion

While these two scandals in themselves were not earth-shaking, they were important both for Brancusi personally, and in legitimising the concept of abstract art in both official and public circles.

Brancusi received considerable support from the arts community for Princess X and also attracted influential critical attention, with an ever-increasing number of articles being published on his work, both in Europe and the United States. To an even greater extent, the long-running but ultimately successful Bird in Space litigation was heavily reported in the press and essentially made Brancusi into a public, albeit controversial, figure [32].

Both works also foreshadowed the problems of interpretation that would later plague much of 20th century art. People were used to viewing traditional artworks in which there was normally no difficulty in deciphering what physically was being depicted – a scene, a person, an object and so on. Generally, the only difficulty was in knowing whether the work was meant to be interpreted literally, or as an allegory, satire or in some other non-literal way.

With these radical new works by Brancusi, however, viewers were required to go one step further back – to decipher what physically they were looking at in the first place. This was further complicated by the fact that the artist might be expressing a purely subjective view of an abstract concept without necessarily any close link to the natural world. The echoes of these difficulties are, of course, still being felt to this day.

© Philip McCouat 2015

Return to HOME

Brancusi received considerable support from the arts community for Princess X and also attracted influential critical attention, with an ever-increasing number of articles being published on his work, both in Europe and the United States. To an even greater extent, the long-running but ultimately successful Bird in Space litigation was heavily reported in the press and essentially made Brancusi into a public, albeit controversial, figure [32].

Both works also foreshadowed the problems of interpretation that would later plague much of 20th century art. People were used to viewing traditional artworks in which there was normally no difficulty in deciphering what physically was being depicted – a scene, a person, an object and so on. Generally, the only difficulty was in knowing whether the work was meant to be interpreted literally, or as an allegory, satire or in some other non-literal way.

With these radical new works by Brancusi, however, viewers were required to go one step further back – to decipher what physically they were looking at in the first place. This was further complicated by the fact that the artist might be expressing a purely subjective view of an abstract concept without necessarily any close link to the natural world. The echoes of these difficulties are, of course, still being felt to this day.

© Philip McCouat 2015

Return to HOME

End Notes

Part 1

[1] 1876-1957. More correctly, “Brâncuși”.

[2] Stéphanie Giry, “An Odd Bird”, Legal Affairs, Sept/Oct 2002, http://www.legalaffairs.org/issues/September-October-2002/story_giry_sepoct2002.msp

[3] A marble version of the same work also exists.

[4] Sanda Miller, Brancusi, Reaktion Books, London, 2010 at 61.

[5] Pontus Hulten et al, Brancusi, Faber and Faber, London, 1988 at 131.

[6] Hulton, op cit at 132.

[7] Roger Devigne, L’Eve Nouvelle, January 1920; Eric Shanes, Constantin Brancusi, Abbeville Press, New York, 1989 at 56.

[8] Sanda Miller, “Brancusi’s women”, Apollo (March 2007), 56 – 63.

[9] Quoted in Miller [note 4] at 60.

[10] Shanes, op cit at 55. According to Hulton, op cit at 130, Brancusi was simply inspired by the “graceful way” the lady gazed at herself in a mirror.

[11] 1882-1962; known to her family as Mimi: Miller, op cit [note 4] at 60.

[12] For a full account of Marie’s remarkable life, see Celia Bertin, Marie Bonaparte: A Life, Harcourt Brace Joyanovich, 1982.

[13] George’s closest friend was his uncle Waldemar, who accompanied the couple on their honeymoon. Waldemar was known as “Papa 2” by the couple’s children: see Bertin, op cit at 94.

[14] Published in the Jnl Bruxelles Médical under the pseudonym A E Narjani.

[15] Marie’s theory is today considered incorrect.

[16] Bertin, op cit at 155,

[17] Miller, op cit [note 4] at 60.

[18] Friedrich Teja Bach and ors, Constantin Brancusi, Exh Cat (1995) at 140; cited at Philadelphia Museum of Art website http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/51035.html

[19] Miller, op cit [note 4] at 62.

[20] Miller, op cit [note 8]

[21] Quoted earlier in this article.

Part 2

[22] This series would preoccupy him for some 20 years.

[23] Giry, op cit.

[24] C Brancusi v United States, Treasury Decisions, 54 no 43063.

[25] United States v Olivotti and Company, Treasury Decisions, 30 no 36309.

[26] For the detail of the court proceedings, I am indebted to Thomas L. Hartshorne’s “Modernism on Trial: C. Brancusi v. United States (1928)”, Journal of American Studies, Vol. 20, No. 1 (April 1986), pp. 93-104.

[27] Editor of Vanity Fair.

[28] Other issues included whether the Bird was simply a copy, rather than an original. The court accepted that it was one of a series of variations on a theme, with different materials and with different proportions, and that each of them were originals in their own right: Hartshorne, op cit.

[29] This question has also tended to get confused with the separate issue of what art is for.

[30] This emphasis was shared even by most of Brancusi’s witnesses.

[31] Giry, op cit.

[32] Sidney Geist, Brancusi, Hacker Art Books, New York, 1983 at 4, 5.

© Philip McCouat 2015

Return to HOME

[1] 1876-1957. More correctly, “Brâncuși”.

[2] Stéphanie Giry, “An Odd Bird”, Legal Affairs, Sept/Oct 2002, http://www.legalaffairs.org/issues/September-October-2002/story_giry_sepoct2002.msp

[3] A marble version of the same work also exists.

[4] Sanda Miller, Brancusi, Reaktion Books, London, 2010 at 61.

[5] Pontus Hulten et al, Brancusi, Faber and Faber, London, 1988 at 131.

[6] Hulton, op cit at 132.

[7] Roger Devigne, L’Eve Nouvelle, January 1920; Eric Shanes, Constantin Brancusi, Abbeville Press, New York, 1989 at 56.

[8] Sanda Miller, “Brancusi’s women”, Apollo (March 2007), 56 – 63.

[9] Quoted in Miller [note 4] at 60.

[10] Shanes, op cit at 55. According to Hulton, op cit at 130, Brancusi was simply inspired by the “graceful way” the lady gazed at herself in a mirror.

[11] 1882-1962; known to her family as Mimi: Miller, op cit [note 4] at 60.

[12] For a full account of Marie’s remarkable life, see Celia Bertin, Marie Bonaparte: A Life, Harcourt Brace Joyanovich, 1982.

[13] George’s closest friend was his uncle Waldemar, who accompanied the couple on their honeymoon. Waldemar was known as “Papa 2” by the couple’s children: see Bertin, op cit at 94.

[14] Published in the Jnl Bruxelles Médical under the pseudonym A E Narjani.

[15] Marie’s theory is today considered incorrect.

[16] Bertin, op cit at 155,

[17] Miller, op cit [note 4] at 60.

[18] Friedrich Teja Bach and ors, Constantin Brancusi, Exh Cat (1995) at 140; cited at Philadelphia Museum of Art website http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/51035.html

[19] Miller, op cit [note 4] at 62.

[20] Miller, op cit [note 8]

[21] Quoted earlier in this article.

Part 2

[22] This series would preoccupy him for some 20 years.

[23] Giry, op cit.

[24] C Brancusi v United States, Treasury Decisions, 54 no 43063.

[25] United States v Olivotti and Company, Treasury Decisions, 30 no 36309.

[26] For the detail of the court proceedings, I am indebted to Thomas L. Hartshorne’s “Modernism on Trial: C. Brancusi v. United States (1928)”, Journal of American Studies, Vol. 20, No. 1 (April 1986), pp. 93-104.

[27] Editor of Vanity Fair.

[28] Other issues included whether the Bird was simply a copy, rather than an original. The court accepted that it was one of a series of variations on a theme, with different materials and with different proportions, and that each of them were originals in their own right: Hartshorne, op cit.

[29] This question has also tended to get confused with the separate issue of what art is for.

[30] This emphasis was shared even by most of Brancusi’s witnesses.

[31] Giry, op cit.

[32] Sidney Geist, Brancusi, Hacker Art Books, New York, 1983 at 4, 5.

© Philip McCouat 2015

Return to HOME