Reflections on a Masterpiece

Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

By Philip McCouat For readers’ comments on this article, see here

Introduction

Part I: The “impossible” perspectives of the painting

Part II: Commodities and the barmaid’s gaze

Introduction

Part I: The “impossible” perspectives of the painting

Part II: Commodities and the barmaid’s gaze

Introduction

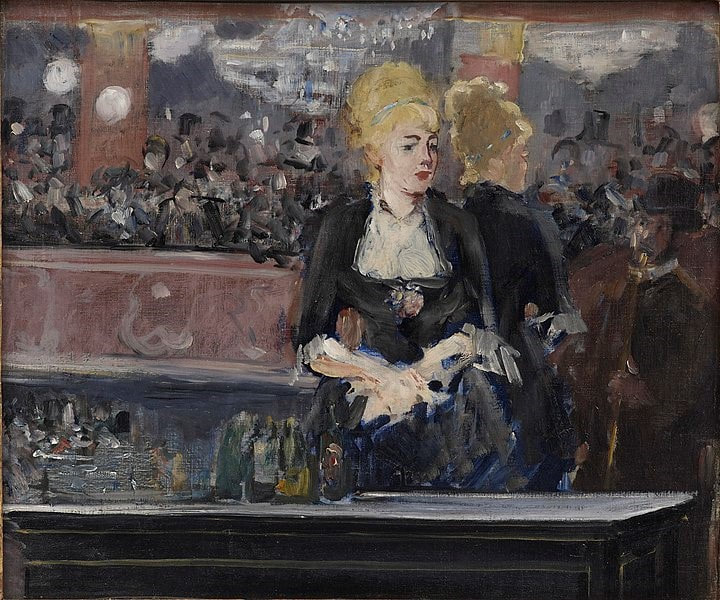

Édouard Manet’s last and perhaps greatest masterpiece – A Bar at the Folies-Bergère – has been described as “one of the canonical images for modernist art history” [1]. Right from the time it first appeared at the prestigious Paris Salon, it has been notorious both for its apparently wilful disregard of perspective, and by the enigmatic role of its central subject, the barmaid. It is this extraordinary painting that we will be examining in this article.

The setting at the Folies-Bergère

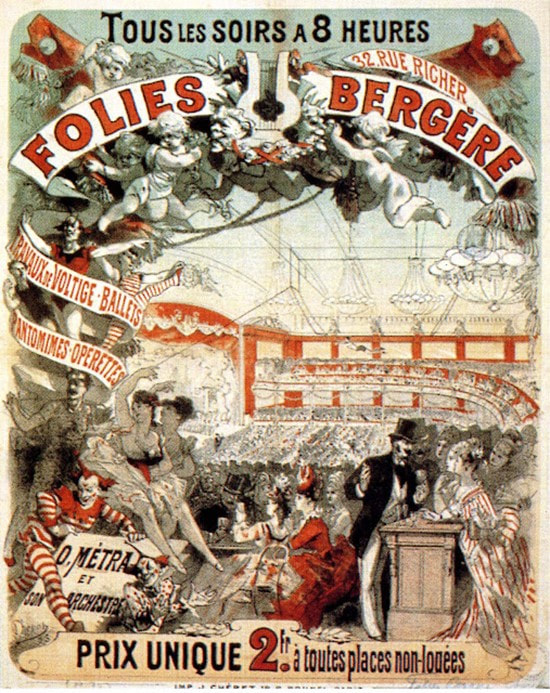

The setting for the painting, the Folies-Bergère, is a famous Parisian nightclub/theatre which opened in 1869 [2]. Traditionally, a night at the Folies-Bergère might have included dancers, pantomime, operetta and even animal acts. Acrobats and trapeze artists were often on show, and were hugely popular [3] – as amusingly evidenced in the painting by the two green-slippered feet dangling in the top left corner [4]. The Folies was also a place for drinking and for romantic or sexual encounters, where men and woman mixed freely, a place where people dressed up and went “to see, and be seen”. It was quite expensive, charging for admission, and had a predominantly middle to upper middle-class clientele. It was the kind of trendy place in which Manet himself and his friends enjoyed.

Part I:

The “impossible” perspectives of the painting

Many first-time viewers of the painting have the impression that it is rather straightforward. As the name would suggest, they see an expansive view of the famous Parisian nightspot, lit by huge chandeliers [5] hanging from the ceiling. In the centre of the painting, facing the viewer, a barmaid stands behind a bar, her hands resting on the edge of the marble top, where there are a number of unopened bottles, a glass bowl of oranges [6] and two roses in a glass. On the right, the viewer sees the back of a barmaid who is attending to a male customer. In the background, behind the central barmaid, our first-time viewer sees a balconied terrace, full of the seated audience for some largely unseen attractions.

A closer examination of the painting, however, reveals that things may not be as they seem. The reason for this is that everything behind the central barmaid is actually just a reflection in a very large mirror attached to the back wall.

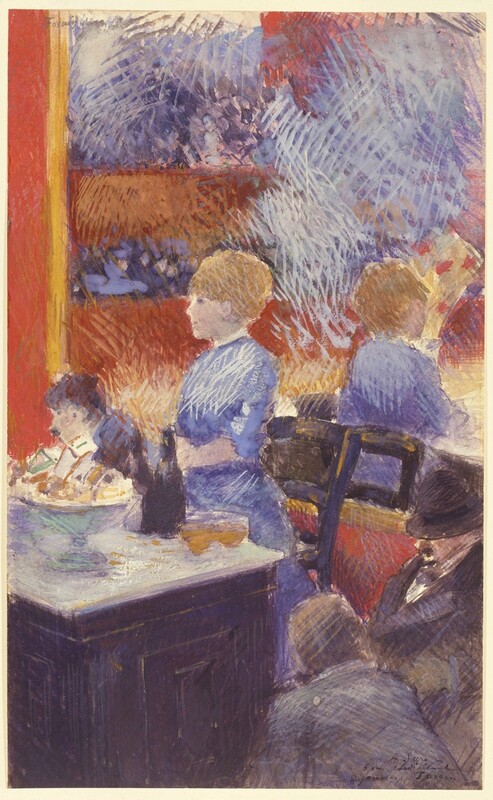

Mirrors were a prominent part of the ambience of the Folies, and were often noted in contemporary descriptions [7], and shown in other depictions of a Folies bar, such as Forain’s painting at Fig 2.

A closer examination of the painting, however, reveals that things may not be as they seem. The reason for this is that everything behind the central barmaid is actually just a reflection in a very large mirror attached to the back wall.

Mirrors were a prominent part of the ambience of the Folies, and were often noted in contemporary descriptions [7], and shown in other depictions of a Folies bar, such as Forain’s painting at Fig 2.

In Manet’s painting, we can see parts of the mirror’s gold frame against the wall behind the central barmaid, at the level of each of her wrists. The existence of the mirror is also why the central barmaid and the products on the bar appear so clearly delineated, whereas every other person in the painting appears a little blurry.

If we accept that there is a mirror, it seemingly becomes clear that the barmaid on the right, with her back to us, is actually just a reflection of the central barmaid. Similarly, the bar that appears at hip level behind the central barmaid is actually just a reflection of the bar in the foreground. And the group of bottles on the bar on the left – champagne, beer and wine -- are also reflected in the mirror, though the reflection is partly obscured by the central barmaid. The mirror also means that the audience we can see, who are watching the trapeze artist or other performances, is actually just a reflection of the real theatre audience which is behind us [8],

However, the reflection in the mirror also gives rise to its own puzzling aspects. These have long vexed many commentators -- as Richard Brettell has observed, "the reflection [in A Bar] has caused more speculation than any depicted mirror in the history of Western art" [9].

If we accept that there is a mirror, it seemingly becomes clear that the barmaid on the right, with her back to us, is actually just a reflection of the central barmaid. Similarly, the bar that appears at hip level behind the central barmaid is actually just a reflection of the bar in the foreground. And the group of bottles on the bar on the left – champagne, beer and wine -- are also reflected in the mirror, though the reflection is partly obscured by the central barmaid. The mirror also means that the audience we can see, who are watching the trapeze artist or other performances, is actually just a reflection of the real theatre audience which is behind us [8],

However, the reflection in the mirror also gives rise to its own puzzling aspects. These have long vexed many commentators -- as Richard Brettell has observed, "the reflection [in A Bar] has caused more speculation than any depicted mirror in the history of Western art" [9].

Reflection of the barmaid and the man

One of the main issues with the mirror concerns the central barmaid. As we seem to be directly in front of her, her reflection should be directly behind her, not way over on the right as it is in the painting. Additionally, that reflection seems to depict a much more thickset woman than the wasp-waisted central barmaid. The reflected barmaid also has less tightly controlled hair, has apparently lost her earrings and, some suggest, may be bending forward a little, rather than standing upright.

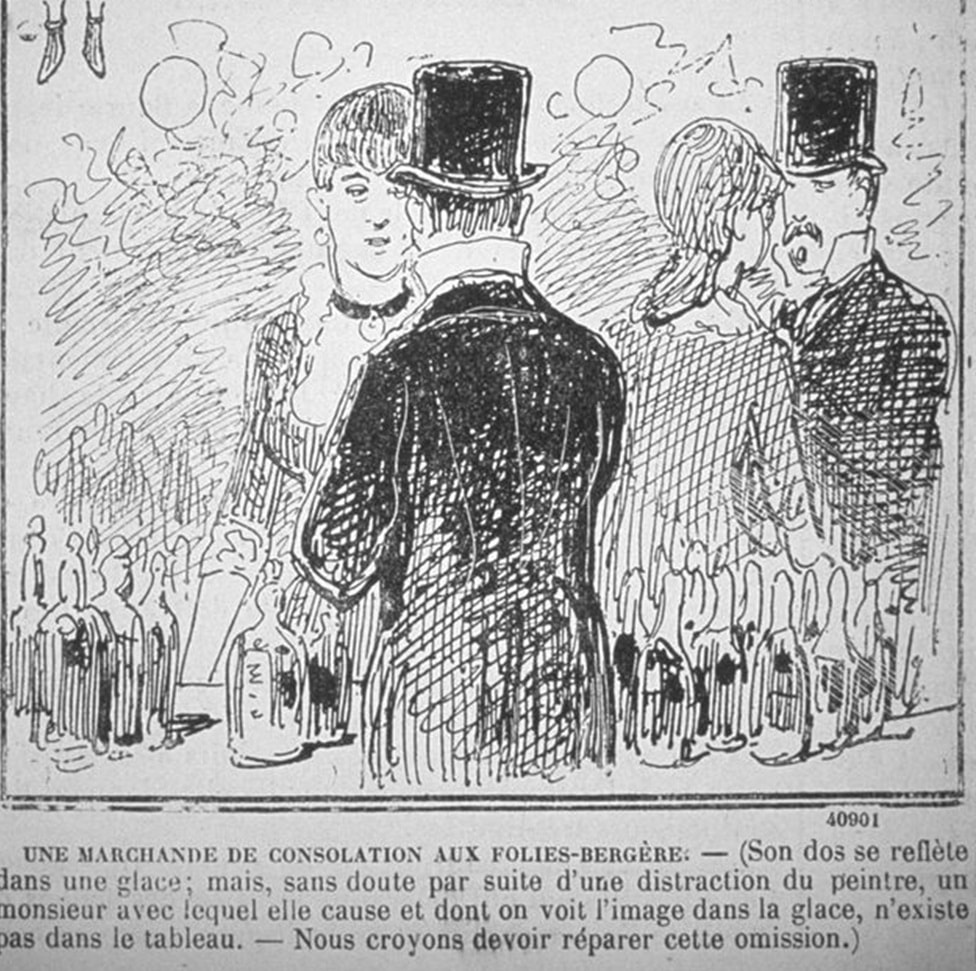

The reflection of the male customer at far right is also problematic. Where is he in ‘reality’? We should be able to see some indication of him on ‘our’ side of the bar, but there is no sign of where he is standing. A satirical caricature of the painting, made in 1882 when it was being exhibited for the first time, ingenuously suggested that the non-appearance of the customer was “presumably due to the painter being distracted”, and helpfully “corrected the omission” by adding the customer back where he supposedly should be (Fig 3).

The reflection of the male customer at far right is also problematic. Where is he in ‘reality’? We should be able to see some indication of him on ‘our’ side of the bar, but there is no sign of where he is standing. A satirical caricature of the painting, made in 1882 when it was being exhibited for the first time, ingenuously suggested that the non-appearance of the customer was “presumably due to the painter being distracted”, and helpfully “corrected the omission” by adding the customer back where he supposedly should be (Fig 3).

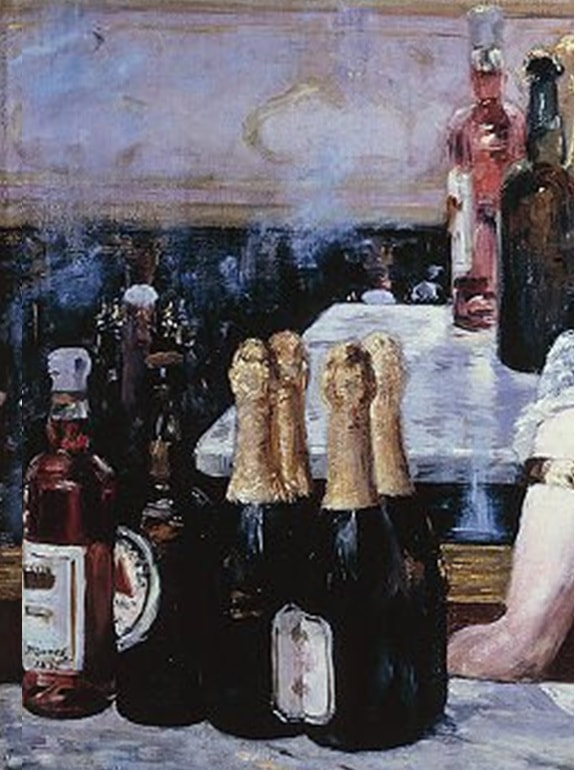

Reflection of the bottles and bar

And there’s a further problem -- the reflection of the bottles, when we look at it more closely, cannot be correct. The ‘real’ bottles are on the inner part of the marbled countertop, next to the barmaid’s hands. But, in the reflection that we can see, they are on the outer part of the countertop. Furthermore, while their apparent reflection includes a similar range of bottles as the real ones, the way in which they are arranged is noticeably different. So, for example, the beer bottle is alongside the grenadine in the near view but at an angle to it in the apparent reflection.

The reflection of the bar itself is also problematic. In the reflection, it seems that it is not really supported by anything, other than the faint suggestion of a table leg. It is not the solid structure as shown in the Forain painting, where the underside would normally have glasses, bottles and other necessaries [10]. Furthermore, given that the reflection is only a metre or so from the ‘real’ bar, there should barely be any angle in the edge of the reflected bar, yet that angle has been markedly exaggerated. We shall be returning to the special significance of this later.

The non-reflection of the customers

At the Folies, the bars were placed around the inside perimeter of the premises, set back against the wall, and there was typically a promenade in front of each bar where people strolled about, or sat at tables, talking and drinking. You can get a flavour of this from the Folies poster at Fig 5. As noted at the time, “everywhere are counters tended by charming waitresses, whose mischievous eyes and gracious smiles attract a crowd of clients” [11].

Logically, these people should be reflected in the mirror. As noted by novelist Guy de Maupassant, the mirrors that commonly appeared behind women working in refreshment counters “reflected [the barmaids’] backs and the faces of the passers by” [12]. Yet in Manet’s painting there is no sign of them.

So, was this just carelessness?

Why would Manet, skilled artist as he was, have got so many things that appear wrong? Was it simply that he was lousy on proportions and perspectives? Did he just not worry about this aspect, or was he just careless? Or was he deliberately creating these apparent distortions?

Certainly, we know from other paintings, such as his notorious Luncheon on the Grass, that he liked to flatten out the picture frame, portray slightly awkward social occasions, and did not always regard himself as bound by the strict requirements of a proper perspective in creating his two-dimensional version of the world. In fact, the creation of spatial ambiguities was one of his main interests. He himself said, “Today’s artist does not say ‘come see works without faults, but ‘come see works that are sincere’ ”[13].

But, while conceding that, the distortions in Folies are so numerous and blatant that they almost appear to be calculated to confuse us. And in fact, we know that Manet took great care in planning this painting. At the time, he was grievously ill, suffering from locomotor ataxia, a side-effect of syphilis, and he would have known that his time was limited (in fact, he died the next year). Unlike the Impressionists, he highly valued getting his paintings accepted by the prestigious Paris Salon for hanging in its annual exhibition. So, he probably knew that this painting might be his last, and it’s likely that he would have been determined to make it an impressive farewell, and to take great care to get it right.

We can actually trace the development of Manet’s thinking by looking at two studies which he did as preparation for the finished painting.

Certainly, we know from other paintings, such as his notorious Luncheon on the Grass, that he liked to flatten out the picture frame, portray slightly awkward social occasions, and did not always regard himself as bound by the strict requirements of a proper perspective in creating his two-dimensional version of the world. In fact, the creation of spatial ambiguities was one of his main interests. He himself said, “Today’s artist does not say ‘come see works without faults, but ‘come see works that are sincere’ ”[13].

But, while conceding that, the distortions in Folies are so numerous and blatant that they almost appear to be calculated to confuse us. And in fact, we know that Manet took great care in planning this painting. At the time, he was grievously ill, suffering from locomotor ataxia, a side-effect of syphilis, and he would have known that his time was limited (in fact, he died the next year). Unlike the Impressionists, he highly valued getting his paintings accepted by the prestigious Paris Salon for hanging in its annual exhibition. So, he probably knew that this painting might be his last, and it’s likely that he would have been determined to make it an impressive farewell, and to take great care to get it right.

We can actually trace the development of Manet’s thinking by looking at two studies which he did as preparation for the finished painting.

Development of the painting: stage #1

The first stage of the painting was done on site, at the Folies itself, with a model who actually worked as a barmaid there. In this study (Fig 6), the barmaid is turning to our right, and her hands are folded on each other in a rather deferential manner. Her hair is piled up on the top of her head and, in general, she conforms to a traditional image of a barmaid.

In this first stage, the viewer sees the scene from a point slightly offset to the right of the edge of the bar, not directly front-on as appears to be the case in the ultimate painting. The location of the barmaid’s reflection in the mirror, slightly to the right of the barmaid, is close to realistic, bearing in mind her own turned posture and our offset point of view. The male customer holds a cane and is almost comically dwarfed by the reflection of the barmaid, seeming to stand in some indeterminate plane, on some much lower level than her -- clearly, his positioning in the painting is still a work in progress. There is also no reflection of the bar or of the bottles.

Development of the painting: stage #2

Due to Manet’s increasing debility and lack of mobility, the second stage of the painting was done in his own studio, with an entirely new model, named Suzon, and a mock-up of the scene, including a marble-topped table, bottles and fruit – though (apparently) not a mirror.

Like the original model, Suzon worked as a barmaid at the Folies, but she is presented as younger, more attractive and more elegant than the original barmaid used by Manet. Her position at the bar now appears front and centre; this is reinforced by the compositional triangle formed by the placement of her arms. We are also closer to her – the lower edge of the painting is now half-way across the marbled bar, instead of being a few paces back, as it was in the first study.

However, contrarily, her reflection in the mirror seems to defy reality by being even further to the right. The reflection of the male customer (still absent on our side of the bar) now appears much further back and at roughly the same level as the barmaid. His cane has atrophied. A reflection of the bar and the bottles now appears for the first time.

It can also be seen that in the finished full-size painting (Fig 1), Manet makes the barmaid even more dominant and central – the top of her head is now almost at the centre of the top edge of the painting. The artist also makes her reflection even more extremely out of place on the right. Despite her front-on appearance, the reflection shows even more of the side of her face than we could see in the second study.

However, contrarily, her reflection in the mirror seems to defy reality by being even further to the right. The reflection of the male customer (still absent on our side of the bar) now appears much further back and at roughly the same level as the barmaid. His cane has atrophied. A reflection of the bar and the bottles now appears for the first time.

It can also be seen that in the finished full-size painting (Fig 1), Manet makes the barmaid even more dominant and central – the top of her head is now almost at the centre of the top edge of the painting. The artist also makes her reflection even more extremely out of place on the right. Despite her front-on appearance, the reflection shows even more of the side of her face than we could see in the second study.

A question of viewpoints and angles

The importance that Manet attached to the painting, and the detailed preparation, strongly suggest that the distortions in the finished painting, far from being due to carelessness or lack of skill, were deliberate and carefully planned. But, if so, the question remains – what effect, if any, were they intended to achieve?

Until comparatively recent times. many commentators concluded that we simply don’t know why, and never will. So, for example, as late as 1996, it was noted that “historians have attacked the problem like sleuths, expecting to find some key to a logical and naturalistic explanation. There is none” [14].

Other commentators, not so pessimistic, have suggested at least partial explanations of the effect that Manet was trying to achieve. One of these is that the reflection of the barmaid and the man is just a fiction, representing a dream that the distracted central barmaid is having about a tryst with him [15]. Another is that the painting provides us with views of the same scene from two different angles. The first angle is what we see if we’re directly in front of the bar. The second is what we’d see if we were placed over on the right-hand side. On this view, Manet is performing almost as a proto-cubist, decades before his time – giving the viewer simultaneous multiple views from different angles of the same subject, though in Manet’s case those views are not combined in the one figure.

A variant of this is that the second view takes place a few moments after the first view. In other words, the image is not static, but rotates as we move past (or around) the barmaid as she stands at the bar [16]. A third variant suggests that the painting is “a composite image implying two (logical, not chronological) moments”, coupled with a pivoting of the mirror [17].

Feel free to take your pick, one of these “two-angles” speculations, may possibly be what Manet was aiming for, but there’s little or no external evidence to support any of them. Furthermore, if there actually are two angles depicted in the one painting, there would presumably be two-angled views of the theatre audience, but this is not evident. In addition, the two-angles theories are not comprehensive, and do not address the problem of the distorted reflection of the bottles on the bar counter.

Until comparatively recent times. many commentators concluded that we simply don’t know why, and never will. So, for example, as late as 1996, it was noted that “historians have attacked the problem like sleuths, expecting to find some key to a logical and naturalistic explanation. There is none” [14].

Other commentators, not so pessimistic, have suggested at least partial explanations of the effect that Manet was trying to achieve. One of these is that the reflection of the barmaid and the man is just a fiction, representing a dream that the distracted central barmaid is having about a tryst with him [15]. Another is that the painting provides us with views of the same scene from two different angles. The first angle is what we see if we’re directly in front of the bar. The second is what we’d see if we were placed over on the right-hand side. On this view, Manet is performing almost as a proto-cubist, decades before his time – giving the viewer simultaneous multiple views from different angles of the same subject, though in Manet’s case those views are not combined in the one figure.

A variant of this is that the second view takes place a few moments after the first view. In other words, the image is not static, but rotates as we move past (or around) the barmaid as she stands at the bar [16]. A third variant suggests that the painting is “a composite image implying two (logical, not chronological) moments”, coupled with a pivoting of the mirror [17].

Feel free to take your pick, one of these “two-angles” speculations, may possibly be what Manet was aiming for, but there’s little or no external evidence to support any of them. Furthermore, if there actually are two angles depicted in the one painting, there would presumably be two-angled views of the theatre audience, but this is not evident. In addition, the two-angles theories are not comprehensive, and do not address the problem of the distorted reflection of the bottles on the bar counter.

An unexpected resolution?

More recently, however, another ingenious and unexpected explanation has emerged which goes a considerable way toward making sense of the problems. This explanation, proposed by Malcolm Park in 2001 [18], is that the painting does not involve two images from two angles -- instead, there is only one image from one, very specific, angle.

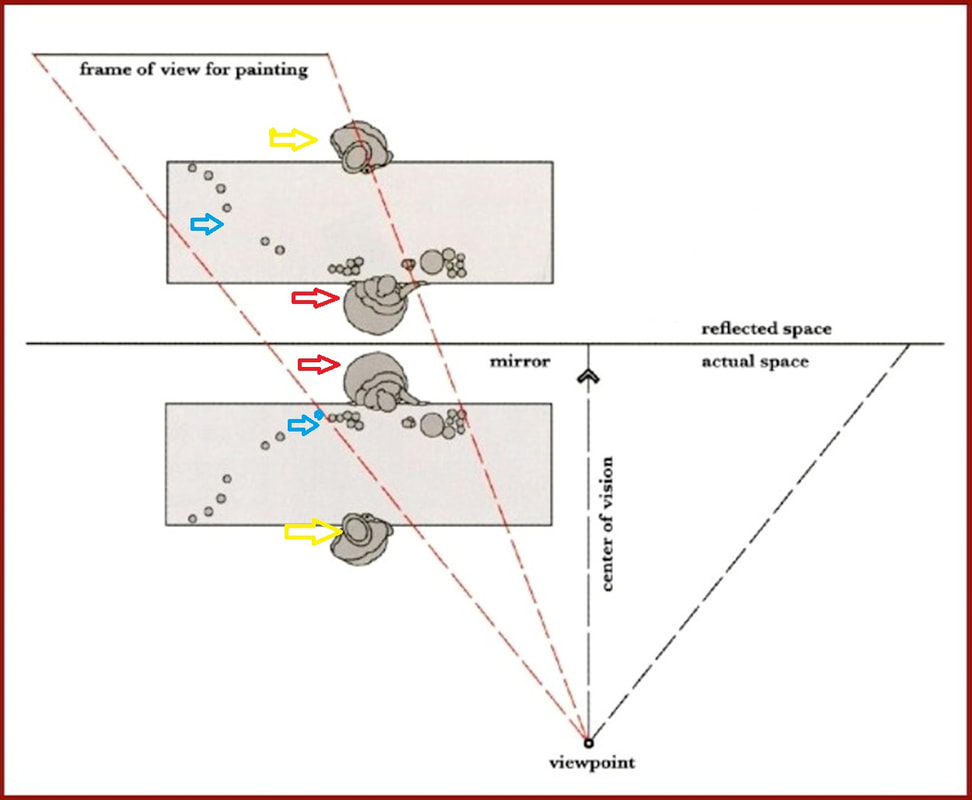

Basing himself on a detailed examination of the layout of the theatre, and the possible positions of the bar, Park was able to identify that this angle was from a viewpoint much further back, and offset to the right. This is shown in this diagram, which repays careful study. It is divided horizontally into actual space and reflected space. Manet’s (and viewers’) viewpoint is at lower right. We have colour-coded each figure, so that both the actual person and their reflection have the same coloured arrow.

Basing himself on a detailed examination of the layout of the theatre, and the possible positions of the bar, Park was able to identify that this angle was from a viewpoint much further back, and offset to the right. This is shown in this diagram, which repays careful study. It is divided horizontally into actual space and reflected space. Manet’s (and viewers’) viewpoint is at lower right. We have colour-coded each figure, so that both the actual person and their reflection have the same coloured arrow.

From this, you can see the barmaid is facing toward the artist, but at an angle across the bar. That angle also makes sense of her reflection being to the right of our viewing frame (though it does not fully explain why her reflection seems more thickset). The male customer is out of our view because he is actually on our left, outside the picture frame: he is looking to the left, possibly gazing at the reflection of the audience in the mirror. The overall effect is that his reflection appears on the far side of the bar, partly obscured by the reflection of the barmaid, giving the erroneous impression that they are close and talking to each other. You can see a similar, incidental effect in Forain’s painting (Fig 2), where the offset viewpoint results in the reflection including what seems to be a bunch of red flowers close to the barmaid’s head, even though there is otherwise no sign of the bunch in the painting.

The riddle of the bottles is also solved – what we originally thought was a reflection of the group of bottles on the bar near the barmaid is actually a reflection of a quite separate arrangement of bottles strung out along the bar to the left.

Artists’ use of offset viewpoints was of course not new. In La Prune (Fig 13), Manet uses a viewpoint off the left which exaggerates the amount to which woman is turning. In L’Absinthe (1876), Degas’ viewpoint off to the left, coupled with the background mirror, illustrates how this creates a displacement of the reflection of the woman’s head. The odd effects that a painter can achieve using a mirror and an off-centre viewpoint had also been demonstrated in Ingres' Portrait of Madame Moitessier (Fig 9), where the viewer is presented with an image that is spatially impossible – the viewer sees the woman from the front, yet the reflection of the side of her head in the mirror only makes sense if we are off on the right-hand side.

The riddle of the bottles is also solved – what we originally thought was a reflection of the group of bottles on the bar near the barmaid is actually a reflection of a quite separate arrangement of bottles strung out along the bar to the left.

Artists’ use of offset viewpoints was of course not new. In La Prune (Fig 13), Manet uses a viewpoint off the left which exaggerates the amount to which woman is turning. In L’Absinthe (1876), Degas’ viewpoint off to the left, coupled with the background mirror, illustrates how this creates a displacement of the reflection of the woman’s head. The odd effects that a painter can achieve using a mirror and an off-centre viewpoint had also been demonstrated in Ingres' Portrait of Madame Moitessier (Fig 9), where the viewer is presented with an image that is spatially impossible – the viewer sees the woman from the front, yet the reflection of the side of her head in the mirror only makes sense if we are off on the right-hand side.

The puzzle of the “frontal” barmaid

However, some difficulties possibly still remain with Park's analysis. The first is that the central barmaid certainly still appears to us viewers as front on, even though Park’s scenario would seemingly require her to be seen at an angle. Park suggests that this is explained by the fact that the barmaid in the painting has actually turned slightly in the direction of the painter. Some support for this is provided by the position of the barmaid’s hips. Her left hip is noticeably higher that her right hip, suggesting that her body has twisted slightly to one side. This is reinforced by the appearance of her left thigh, which looks to be at quite a different angle to the bar than her right thigh. We don’t tend to notice this, as the full extent of this angle is artfully disguised by the placement of glass with roses and her left forearm.

Confirmation that this slight turning of the barmaid would be sufficient to create a front-on appearance for the viewer is provided by the following posed photograph of Park’s scenario.

Confirmation that this slight turning of the barmaid would be sufficient to create a front-on appearance for the viewer is provided by the following posed photograph of Park’s scenario.

The anomalous reflection of the bar

This leaves just one more tantalising issue. This arises from the reflection of the edge of the bar on the left of the barmaid. According to Park’s scenario, that reflection should extend beyond the left edge of the picture frame. Yet, in the painting, it has been radically shortened. Furthermore, given that the reflection is only a metre or so from the ‘real’ bar, there should barely be any angle in the edge of the reflected bar, yet that angle has been markedly exaggerated.

Park concedes that his basic scenario cannot account for this anomaly, but argues that the reflected bar must be seen as an intentional device used by Manet “to counteract the offset spatial shaping” [19] -- in other words, Manet has deliberately introduced this anomaly to reinforce the intended full-frontal appearance of the barmaid. It may be relevant here that if you extend upwards the angle of the edge of the reflected bar, it ends neatly at the top of the barmaid’s head, forming one side of the central triangle that reinforces the barmaid’s apparent frontal stance.

In summary, Park has been able to demonstrate that, contrary to earlier views, the major apparent distortions in the painting are actually quite realistic, and that the painting can be explained, subject to some possible qualifications already noted, according to normal rules governing mirrored reflections.

Park concedes that his basic scenario cannot account for this anomaly, but argues that the reflected bar must be seen as an intentional device used by Manet “to counteract the offset spatial shaping” [19] -- in other words, Manet has deliberately introduced this anomaly to reinforce the intended full-frontal appearance of the barmaid. It may be relevant here that if you extend upwards the angle of the edge of the reflected bar, it ends neatly at the top of the barmaid’s head, forming one side of the central triangle that reinforces the barmaid’s apparent frontal stance.

In summary, Park has been able to demonstrate that, contrary to earlier views, the major apparent distortions in the painting are actually quite realistic, and that the painting can be explained, subject to some possible qualifications already noted, according to normal rules governing mirrored reflections.

Part II:

Commodities and the barmaid’s gaze

We now turn to the second major aspect of the painting – the case of the enigmatic barmaid.

In the late 19th century, urban France was marked by rapid developments in the production of manufactured goods, driven by the Industrial Revolution, and the associated growth of mass consumption. In Paris, in particular, the emergence of huge department stores, such as Bon Marché, was emblematic of the emerging culture, and helped drive it. Particularly for women, shopping in these paradises of seductively-displayed commodities became an experience to be desired, not a chore. Relative novelties such as ready-to-wear clothing become widespread, indirectly leading to the development of the fashion industry for which Paris ultimately became famous [20]. Baron Haussman’s massive urban renewal of Paris, with its expansive public parks and gardens, produced “new sites for sociability and display” [21]. And the opening of spectacular mass entertainment venues such as the Folies-Bergère, also contributed to Paris becoming a showcase for spectacles.

In the late 19th century, urban France was marked by rapid developments in the production of manufactured goods, driven by the Industrial Revolution, and the associated growth of mass consumption. In Paris, in particular, the emergence of huge department stores, such as Bon Marché, was emblematic of the emerging culture, and helped drive it. Particularly for women, shopping in these paradises of seductively-displayed commodities became an experience to be desired, not a chore. Relative novelties such as ready-to-wear clothing become widespread, indirectly leading to the development of the fashion industry for which Paris ultimately became famous [20]. Baron Haussman’s massive urban renewal of Paris, with its expansive public parks and gardens, produced “new sites for sociability and display” [21]. And the opening of spectacular mass entertainment venues such as the Folies-Bergère, also contributed to Paris becoming a showcase for spectacles.

The role of the barmaid

It has often been argued that these trends are reflected in Manet’s painting. These arguments have largely centred on the appearance and role of the barmaid and what she is “selling”.

So, let’s look at her a little closer. She appears well-dressed and well groomed, her cheeks are rouged, her dress is cut low at the front, though this is partly obscured by a corsage of flowers. Her tight-fitting outfit has been described as the Folies regulation uniform [22], though a far plainer outfit is being worn by the Folies barmaid depicted in Forain’s painting at Fig 2. For what it’s worth, the barmaid depicted in the Folies poster at Fig 5 appears to be wearing an open-necked, long flowing dress.

The barmaid’s upright stance, with both arms outstretched and hands resting on the bar, suggest that she is outwardly in control, yet she is does not directly confront the viewer – her eyes do not meet ours’, but instead are downcast, averted to our left. Her expression is famously ambiguous, so much so that she has been described as “a Mona Lisa of barmaids” [23].

So, let’s look at her a little closer. She appears well-dressed and well groomed, her cheeks are rouged, her dress is cut low at the front, though this is partly obscured by a corsage of flowers. Her tight-fitting outfit has been described as the Folies regulation uniform [22], though a far plainer outfit is being worn by the Folies barmaid depicted in Forain’s painting at Fig 2. For what it’s worth, the barmaid depicted in the Folies poster at Fig 5 appears to be wearing an open-necked, long flowing dress.

The barmaid’s upright stance, with both arms outstretched and hands resting on the bar, suggest that she is outwardly in control, yet she is does not directly confront the viewer – her eyes do not meet ours’, but instead are downcast, averted to our left. Her expression is famously ambiguous, so much so that she has been described as “a Mona Lisa of barmaids” [23].

The barmaid’s downward gaze

Before we delve into the possible meanings of the barmaid’s gaze, it is worth noting how often the women in Manet’s paintings appear to be asserting their own self-possessed independence, no matter what their particular social circumstances may be. For example, in Manet’s famous paintings of naked women – Olympia and Luncheon on the Grass – the women frankly confront the viewer, confident in their own bodies, and not showing any concern for issues such as stereotypical attractiveness or traditional morality. And in other paintings, set in more conventional social situations, Manet portrays women defying social expectations by pointedly looking off into the distance, or away from their companions with distracted, often-bored expressions. Consider these examples:

So, it’s possible that the barmaid’s expression in A Bar, turning distractedly away from the viewer (and the rest of the world), is simply typical of how Manet often portrays women, and is not necessarily attributable to the particular circumstances of her working at the Folies. This however is not a view that is taken by most commentators, who consider that, in the context of this painting it signifies something far more specific.

Most (though not all) commentators have taken the view that the barmaid’s downward gaze suggests that she is disengaged from the rather frantic “good-time” activities at the nightspot, and is not happy about something. But there are many views about what that “something” may be.

So, for example, it has been variously suggested that:

(1) she is physically exhausted at the end of a long shift standing up;

(2) she is fed up with her boring working class job in which she is just a cog in the wheel of industry;

(3) in a male-dominated society [24], she is sick of creepy middle- to upper-class men who expect and demand her pleasantness, attention and service;

(4) she is day-dreaming of nothing in particular, or of being somewhere, or being someone else, or being with someone else (maybe the top-hatted man)

(5) she is regretting the constricting corset that she has to wear to produce her wasp-like waist or, more generally, the never-ending efforts that must be taken to make herself perpetually attractive to men;

(6) she is repelled by the growing realisation that she may be regarded as a commodity, like the liquor on the bar in front of her;

(7) more specifically, she is resentful at the expectation laid on her by customers (and possibly the Folies management) that she might provide sexual services; or

(8) all or any combination of the above.

Most (though not all) commentators have taken the view that the barmaid’s downward gaze suggests that she is disengaged from the rather frantic “good-time” activities at the nightspot, and is not happy about something. But there are many views about what that “something” may be.

So, for example, it has been variously suggested that:

(1) she is physically exhausted at the end of a long shift standing up;

(2) she is fed up with her boring working class job in which she is just a cog in the wheel of industry;

(3) in a male-dominated society [24], she is sick of creepy middle- to upper-class men who expect and demand her pleasantness, attention and service;

(4) she is day-dreaming of nothing in particular, or of being somewhere, or being someone else, or being with someone else (maybe the top-hatted man)

(5) she is regretting the constricting corset that she has to wear to produce her wasp-like waist or, more generally, the never-ending efforts that must be taken to make herself perpetually attractive to men;

(6) she is repelled by the growing realisation that she may be regarded as a commodity, like the liquor on the bar in front of her;

(7) more specifically, she is resentful at the expectation laid on her by customers (and possibly the Folies management) that she might provide sexual services; or

(8) all or any combination of the above.

So, is the barmaid a commodity?

Prominently displayed on the bar in front of the barmaid are the commodities available for sale -- a still life of bottles of alcohol and oranges in a bowl. Manet even signs and dates the label on the wine bottle at far left. In so doing, it’s been suggested, he is making an ironical comment on the commercial status of his own work [25].

But perhaps the alcohol and the oranges are not all that’s for sale. It’s been suggested that the barmaid herself could be seen as an additional, attractively pre-packaged commodity. In support of this, it has been noted that various aspects of her physical appearance seem to be echoed in the products that she is selling -- her narrow waist reflects the shape of the glass bowl of oranges, the cuff of her right sleeve mimics a label on the bottles, the gold bracelets on her arms reflect the gold tops of the unopened champagne bottles, her dark clothes reflect the bottles themselves, and so on [26].

It is also often noted that one of the brands of alcohol in the benchtop is the British beer Bass, specially catering for the numerous British tourists, with a distinctive red triangle logo, which apparently happened to be first registered trademark in the world (Fig 16). Some regard this as highly significant -- almost an early form of product placement -- especially as the red triangle is said to be echoed in the corsage of flowers on the barmaid’s chest [27].

But perhaps the alcohol and the oranges are not all that’s for sale. It’s been suggested that the barmaid herself could be seen as an additional, attractively pre-packaged commodity. In support of this, it has been noted that various aspects of her physical appearance seem to be echoed in the products that she is selling -- her narrow waist reflects the shape of the glass bowl of oranges, the cuff of her right sleeve mimics a label on the bottles, the gold bracelets on her arms reflect the gold tops of the unopened champagne bottles, her dark clothes reflect the bottles themselves, and so on [26].

It is also often noted that one of the brands of alcohol in the benchtop is the British beer Bass, specially catering for the numerous British tourists, with a distinctive red triangle logo, which apparently happened to be first registered trademark in the world (Fig 16). Some regard this as highly significant -- almost an early form of product placement -- especially as the red triangle is said to be echoed in the corsage of flowers on the barmaid’s chest [27].

The barmaid as a seller of herself

So, if the barmaid is a commodity, what aspect of her is being sold here? This question is closely tied to the particular interpretation that one places on the barmaid’s expression.

One obvious commodity is the physical labour that she is selling. She herself is working class, part of the huge mass of workers increasingly engaged in industry. In the context of the Folies, her tiring and menial task, presumably poorly paid, is to help ensure that the cashed-up middle class clientele can indulge themselves in their discretionary pleasure-seeking. In these circumstances it would be understandable that she could feel alienated and undervalued.

The barmaid is also expected to “sell” other of her female personal attributes, even if it is only her “mischievous eyes” or “gracious smile”[28]. Some commentators, however, have taken this further by arguing that the barmaid is intended to be seen as a prostitute or courtesan (or something in-between), and that she can therefore be interpreted as selling not only her labour, her pleasing looks, and the products on the bar, but also her sexual services.

Certainly, male treatment of any sort of barmaid can be dismissive or unsavoury, particularly at a place like the Folies, where it was believed that some of the barmaids were sexually available. It is interesting that the cartoonist in Fig 3 describes the barmaid as a “merchant of consolation”, presumably not just in the form of alcohol. But this in itself does not establish that Manet was intending that the barmaid here should be seen as falling into that category.

Some commentators have considered that the supposed conversation between the barmaid and the male customer indicates that she is not selling him a drink, or just talking, but is making a sexual assignation. It has also been suggested, with the benefit of vivid imagination, that the reflection of the barmaid shows her leaning slightly toward the customer, in an attitude that is more engaging and solicitous, “warmer, gentler, eager to please”[29]; and that she was “making eyes“ at the man [30].

These, however, are just speculations – how could you legitimately identify what a person is saying or feeling when they have their back to you? – and in any event, their basis collapses entirely if we accept Park’s analysis, in which the man’s real position is off to the left, and there is no longer the possibility that they were even conversing in the first place, let alone being flirtatious or licentious.

Some commentators have nevertheless argued that there are also spicy implications in details such as the triangle formed by the barmaid’s clothing in the area of her groin [31], the supposedly titillating presence of the corsage in her bosom (notwithstanding that that there’s not even a hint of rounded flesh around it); the presence of oranges in the glass bowl (supposedly a motif used by Manet for prostitution); the supposed similarity of her pose with popular depictions of the Virgin Mary stretching out her arms (which is said to raise issues over the extent to which the barmaid is a “virgin and/or whore”) [32]; and the inevitably “phallic” (albeit almost invisible) walking cane being held by the man [33].

To me, however, these seem far too selective and thin as a basis for interpreting the painting, particularly if we accept that there is no conversation going on with the customer in any event.

One obvious commodity is the physical labour that she is selling. She herself is working class, part of the huge mass of workers increasingly engaged in industry. In the context of the Folies, her tiring and menial task, presumably poorly paid, is to help ensure that the cashed-up middle class clientele can indulge themselves in their discretionary pleasure-seeking. In these circumstances it would be understandable that she could feel alienated and undervalued.

The barmaid is also expected to “sell” other of her female personal attributes, even if it is only her “mischievous eyes” or “gracious smile”[28]. Some commentators, however, have taken this further by arguing that the barmaid is intended to be seen as a prostitute or courtesan (or something in-between), and that she can therefore be interpreted as selling not only her labour, her pleasing looks, and the products on the bar, but also her sexual services.

Certainly, male treatment of any sort of barmaid can be dismissive or unsavoury, particularly at a place like the Folies, where it was believed that some of the barmaids were sexually available. It is interesting that the cartoonist in Fig 3 describes the barmaid as a “merchant of consolation”, presumably not just in the form of alcohol. But this in itself does not establish that Manet was intending that the barmaid here should be seen as falling into that category.

Some commentators have considered that the supposed conversation between the barmaid and the male customer indicates that she is not selling him a drink, or just talking, but is making a sexual assignation. It has also been suggested, with the benefit of vivid imagination, that the reflection of the barmaid shows her leaning slightly toward the customer, in an attitude that is more engaging and solicitous, “warmer, gentler, eager to please”[29]; and that she was “making eyes“ at the man [30].

These, however, are just speculations – how could you legitimately identify what a person is saying or feeling when they have their back to you? – and in any event, their basis collapses entirely if we accept Park’s analysis, in which the man’s real position is off to the left, and there is no longer the possibility that they were even conversing in the first place, let alone being flirtatious or licentious.

Some commentators have nevertheless argued that there are also spicy implications in details such as the triangle formed by the barmaid’s clothing in the area of her groin [31], the supposedly titillating presence of the corsage in her bosom (notwithstanding that that there’s not even a hint of rounded flesh around it); the presence of oranges in the glass bowl (supposedly a motif used by Manet for prostitution); the supposed similarity of her pose with popular depictions of the Virgin Mary stretching out her arms (which is said to raise issues over the extent to which the barmaid is a “virgin and/or whore”) [32]; and the inevitably “phallic” (albeit almost invisible) walking cane being held by the man [33].

To me, however, these seem far too selective and thin as a basis for interpreting the painting, particularly if we accept that there is no conversation going on with the customer in any event.

Conclusions

Depicting a slice of modern life, as Manet has done here, does not necessarily mean that he is critiquing it or praising it -- it is possible (though not necessarily easy) to be an entirely passive observer. But Manet here is not passive, for he has introduced two major, unexpected features – the averted downward gaze of the barmaid, and the seemingly anomalous existence of her reflection with the top-hatted man.

We have seen that on Park’s analysis, the main problems with the reflected image can be solved, though as he concedes, to some extent the painting remains “open-ended, elusive and beyond our reach” [34]. If you reject that analysis, you are basically forced back to the partial two-angles explanations which – to me at least -- are far less comprehensive and less persuasive. Alternatively, of course, you can just be happy to accept that the painting makes no perspectival sense, or that there is no mirror, or that the supposed mirror is another painting, so what are we all worrying about!

Turning to the barmaid’s gaze, my personal feeling is that Manet deliberately leaves the narrative open. The point is not to come to a definitive conclusion as whether or not the barmaid is a prostitute, or “available”, or precisely what she is downcast about. The important thing is that her gaze causes viewers to think – it encourages them to wonder about what it is that is making her have that expression. Is it her role as a woman in a male-dominant society? As a worker in a menial, tiring and uninspiring job serving pleasure-seekers? As a commodity in a process of industrialisation? As a perceived provider of sexual services? Or as something else?

The stereotypical male gaze, focusing on an attractive woman’s external appearance or availability, is thus replaced by an enquiry into which of the multitude of possible legitimate grievances this woman may have. Which, I think, is a positive ■

© Philip McCouat 2024. First published February 2024

We welcome your comments on this article.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Reflections on a Masterpiece: Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère”, Journal of Art in Society, February 2024

Return to HOME

We have seen that on Park’s analysis, the main problems with the reflected image can be solved, though as he concedes, to some extent the painting remains “open-ended, elusive and beyond our reach” [34]. If you reject that analysis, you are basically forced back to the partial two-angles explanations which – to me at least -- are far less comprehensive and less persuasive. Alternatively, of course, you can just be happy to accept that the painting makes no perspectival sense, or that there is no mirror, or that the supposed mirror is another painting, so what are we all worrying about!

Turning to the barmaid’s gaze, my personal feeling is that Manet deliberately leaves the narrative open. The point is not to come to a definitive conclusion as whether or not the barmaid is a prostitute, or “available”, or precisely what she is downcast about. The important thing is that her gaze causes viewers to think – it encourages them to wonder about what it is that is making her have that expression. Is it her role as a woman in a male-dominant society? As a worker in a menial, tiring and uninspiring job serving pleasure-seekers? As a commodity in a process of industrialisation? As a perceived provider of sexual services? Or as something else?

The stereotypical male gaze, focusing on an attractive woman’s external appearance or availability, is thus replaced by an enquiry into which of the multitude of possible legitimate grievances this woman may have. Which, I think, is a positive ■

© Philip McCouat 2024. First published February 2024

We welcome your comments on this article.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Reflections on a Masterpiece: Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère”, Journal of Art in Society, February 2024

Return to HOME

end notes

1] Griselda Pollock, “The View from Elsewhere”, in Bradford R Collins (ed), 12 Views of Manet’s Bar, Princeton University Press 1996, at 378. The painting is referred to subsequently in this article as “A Bar”

[2] “Bergère” reflects the name of a nearby street

[3] Albert Boime, “Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère as an Allegory of Nostalgia”, in Collins, op cit at 59

[4] A similar detail appears in Manet’s Masked Ball at the Opera (1873)

[5] Powered by recently-introduced electricity

[6] Or possibly tangerines, or clementines

[7] A number of these are cited in Boime, op cit at 48 It has occasionally been suggested that, contrary to objective reality, there was no wall behind the barmaid, just an alternative reality, or even just another huge painting

[8] Interestingly, one of the audience members highlighted by Manet, of a woman close to the balcony watching intently through binoculars, calls to mind a similar image by the Impressionist Mary Cassatt in At the Opera (1879)

[9] Cited in Malcolm Park, “Edouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies Bergere”, https://docplayer.net/41499123-Edouard-manet-s-a-bar-at-the-folies-bergere-1.html (2012). It is interesting that another famous use of a mirror image in a painting was in Las Meninas (1656) by Diego Velàzquez, a painter whom Manet greatly admired

[10] It’s possible that this has come about because Manet was doing most of his painting in the studio, using a mock-up of the setting, with an ordinary table replacing the actual bar

[11] Contemporary account, cited in Bradford R Collins “The Dialectics of Desire, the Narcissism of Authorship: A Male interpretation of the Psychological Origins of Manet’s Bar”, in Collins, op cit, at 122

[12] From his novel Bel Ami, cited by Boime, op cit at 48. Emphasis added

[13] Cited in Richard Schiff, “Introduction”, in Collins, op cit, at 8

[14] Anne C Hanson. Edouard Manet 1832-1883 (Exhibition Catalogue) 1996, at 185

[15] Boime, op cit at 51ff; David Jones, “Manet’s Bar at the Folies Bergère: Consumer Culture and the Commodification of the Feminine”, Confluence, Vol XXII, Fall 2016

[16] Boime, op cit at 54; Sue Rowe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists, Chatto & Windus, London, 2006, at 232

[17] Thierry de Duve, “Intentionality and Art Critical Methodology: A Case Study”, Nonsite.org July 2012 https://nonsite.org/intentionality-and-art-historical-methodology-a-case-study/

[18] M. Park, 'Ambiguity, and the engagement of spatial illusion within the surface of Manet's paintings', Ph.D diss., (University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2001) file:///C:/Users/user/Downloads/Park-014176882-014197219%20(2).pdf ; and “Edouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies Bergère”, https://docplayer.net/41499123-Edouard-manet-s-a-bar-at-the-folies-bergere-1.html file:///C:/Users/user/Downloads/Park-014176882-014197219%20(1).pdf

[19] Park, op cit

[20] Boime, op cit at 49; David Jones, op cit

[21] Justine De Young, “Representing the Modern Woman: the Fashion Plate Reconsidered (1865–75),” in Women, Femininity and the Public Square in European Visual Culture, 1789-1914 (ed. Temma Balducci and Heather Belnap Jensen; Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2014, at 98

[22] Adolph Tabarant, Manet et ses Oeuvres (1947), cited in Collins, op cit at 118

[23] Cited in Steven Z Levine, “Manet’s Man Meets the Gleam of Her Gaze: A Psychoanalytic Novel” in Collins, op cit at 271

[24] Significantly, French women did not even get the right to vote until the 1940s

[25] Ruth E. Iskin, “Selling, Seduction, and Soliciting the Eye: Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergère,” The Art Bulletin 77 (March 1995): 30, 31

[26] Carol Armstrong, “Fracturing Femininity: Manet’s ‘Before the Mirror,’” October 74 (Autumn 1995): 102

[27] Personally, I think that the corsage more resembles the roses in the glass

[28] Collins [see note 11] in Collins, op cit at 123

[29] Jack Flam, “Looking into the Abyss: The Poetics of Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère , in Collins, op cit, at 167

[30] Cited by Flam, op cit at 174; see also Boime, op cit at 58

[31] Flam, op cit at 167

[32] Michael Paul Driskel, “On Monet’s Binarism: Virgin and/or Whore at the Folies-Bergère” in Collins, op cit at 153. To me, the claimed similarity seems remote

[33] Collins [see note 11], op cit at 121. Thank heavens that he is not also smoking a cigar

[34] Park, op cit

© Philip McCouat 2024. First published February 2024

Return to HOME

[2] “Bergère” reflects the name of a nearby street

[3] Albert Boime, “Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère as an Allegory of Nostalgia”, in Collins, op cit at 59

[4] A similar detail appears in Manet’s Masked Ball at the Opera (1873)

[5] Powered by recently-introduced electricity

[6] Or possibly tangerines, or clementines

[7] A number of these are cited in Boime, op cit at 48 It has occasionally been suggested that, contrary to objective reality, there was no wall behind the barmaid, just an alternative reality, or even just another huge painting

[8] Interestingly, one of the audience members highlighted by Manet, of a woman close to the balcony watching intently through binoculars, calls to mind a similar image by the Impressionist Mary Cassatt in At the Opera (1879)

[9] Cited in Malcolm Park, “Edouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies Bergere”, https://docplayer.net/41499123-Edouard-manet-s-a-bar-at-the-folies-bergere-1.html (2012). It is interesting that another famous use of a mirror image in a painting was in Las Meninas (1656) by Diego Velàzquez, a painter whom Manet greatly admired

[10] It’s possible that this has come about because Manet was doing most of his painting in the studio, using a mock-up of the setting, with an ordinary table replacing the actual bar

[11] Contemporary account, cited in Bradford R Collins “The Dialectics of Desire, the Narcissism of Authorship: A Male interpretation of the Psychological Origins of Manet’s Bar”, in Collins, op cit, at 122

[12] From his novel Bel Ami, cited by Boime, op cit at 48. Emphasis added

[13] Cited in Richard Schiff, “Introduction”, in Collins, op cit, at 8

[14] Anne C Hanson. Edouard Manet 1832-1883 (Exhibition Catalogue) 1996, at 185

[15] Boime, op cit at 51ff; David Jones, “Manet’s Bar at the Folies Bergère: Consumer Culture and the Commodification of the Feminine”, Confluence, Vol XXII, Fall 2016

[16] Boime, op cit at 54; Sue Rowe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists, Chatto & Windus, London, 2006, at 232

[17] Thierry de Duve, “Intentionality and Art Critical Methodology: A Case Study”, Nonsite.org July 2012 https://nonsite.org/intentionality-and-art-historical-methodology-a-case-study/

[18] M. Park, 'Ambiguity, and the engagement of spatial illusion within the surface of Manet's paintings', Ph.D diss., (University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2001) file:///C:/Users/user/Downloads/Park-014176882-014197219%20(2).pdf ; and “Edouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies Bergère”, https://docplayer.net/41499123-Edouard-manet-s-a-bar-at-the-folies-bergere-1.html file:///C:/Users/user/Downloads/Park-014176882-014197219%20(1).pdf

[19] Park, op cit

[20] Boime, op cit at 49; David Jones, op cit

[21] Justine De Young, “Representing the Modern Woman: the Fashion Plate Reconsidered (1865–75),” in Women, Femininity and the Public Square in European Visual Culture, 1789-1914 (ed. Temma Balducci and Heather Belnap Jensen; Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2014, at 98

[22] Adolph Tabarant, Manet et ses Oeuvres (1947), cited in Collins, op cit at 118

[23] Cited in Steven Z Levine, “Manet’s Man Meets the Gleam of Her Gaze: A Psychoanalytic Novel” in Collins, op cit at 271

[24] Significantly, French women did not even get the right to vote until the 1940s

[25] Ruth E. Iskin, “Selling, Seduction, and Soliciting the Eye: Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergère,” The Art Bulletin 77 (March 1995): 30, 31

[26] Carol Armstrong, “Fracturing Femininity: Manet’s ‘Before the Mirror,’” October 74 (Autumn 1995): 102

[27] Personally, I think that the corsage more resembles the roses in the glass

[28] Collins [see note 11] in Collins, op cit at 123

[29] Jack Flam, “Looking into the Abyss: The Poetics of Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère , in Collins, op cit, at 167

[30] Cited by Flam, op cit at 174; see also Boime, op cit at 58

[31] Flam, op cit at 167

[32] Michael Paul Driskel, “On Monet’s Binarism: Virgin and/or Whore at the Folies-Bergère” in Collins, op cit at 153. To me, the claimed similarity seems remote

[33] Collins [see note 11], op cit at 121. Thank heavens that he is not also smoking a cigar

[34] Park, op cit

© Philip McCouat 2024. First published February 2024

Return to HOME