The Two women in White

Wilkie Collins’ bestselling novel and Whistler’s outrageous portrait

By Philip McCouat For readers' comments on this article, see here

INTRODUCTION

In the early 1860s, Britain found itself in the thrall of not just one, but two mysterious Women in White. Both were highly influential in creating new genres in their field. One was fundamental to the creation of new literary form, the sensation novel. The other, which has been described as “one of the most innovative paintings of the nineteenth century” [1], was influential in departing from the narrative style of most 19th century painting, in favour of the more modern idea of “art for art’s sake”. Both, in their own way, involved mysteries; and both challenged society’s norms of legitimate art.

In this article we examine these two trendsetting creations: Wilkie Collins’ novel The Woman in White; and James McNeill Whistler’s supposedly-unrelated painting of the same name [2].

In this article we examine these two trendsetting creations: Wilkie Collins’ novel The Woman in White; and James McNeill Whistler’s supposedly-unrelated painting of the same name [2].

PART 1: COLLINS’ WOMAN IN WHITE

A sensational arrival

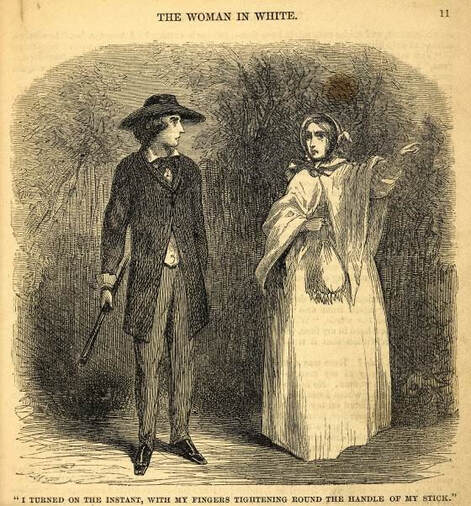

On 26 November 1859, readers opened Charles Dickens's weekly magazine All the Year Round to find the concluding instalment of A Tale of Two Cities, and, immediately following it, the opening instalment of a new novel The Woman in White [3]. The author was a minor novelist called Wilkie Collins, a close friend, collaborator and travelling companion of Charles Dickens, who had personally commissioned the book.

Starting with a chance moonlit encounter with a mysterious wraith-like, white-clad woman, the story centres on a cunning conspiracy by a corrupt aristocrat, aided by his wily Italian associate, to financially exploit his wife’s fortune and protect a dark secret. The story proved to be a wild, runaway success with the public, with its novelties exploding on its British readership “like a bombshell” [4]. As a serial, it lifted the circulation of All the Year Round to record high levels; and the first printing of 1,000 copies of the bound three-volume edition in 1860 sold out on publication day. The book also made Collins rich and famous. When a prominent publisher made a £5,000 bid for his next novel, Collins wrote exultantly to his mother, "FIVE THOUSAND POUNDS!!!!!! Ha! ha! ha! Five thousand pounds, for nine months or, at most a year's work – nobody but Dickens has made as much." [5]

The elements of sensation

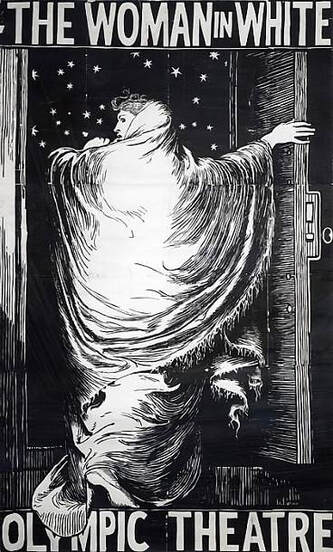

In the more than a century and a half since then, Collins’ book has never been out of print and is still enjoying considerable success, with numerous reissues and stage and screen adaptations, including Andrew Lloyd Webber’s 2004 stage musical and a 2018 BBC television mini-series.

The book is now generally regarded as the first sensation novel, an influential genre of Victorian-era fiction – a precursor of modern genre of detective fiction -- which “fused the apprehensive thrills of Gothic literature with the psychological realism of the domestic novel” [6]. As Matthew Sweet says, “Using a high-impact style of narrative that put its characters through a series of extreme mental experiences, Collins.... brought the terrors of the Gothic novel down from mouldering Italian castles into the back parlours and drawing rooms of a recognisably modern, middle class Victorian England…. As Henry James commented, ‘to Mr Collins belongs the credit of having introduced into fiction those most mysterious mysteries of mysteries, the mysteries which are at our own doors’.” [7]. Collins himself called it “the secret theatre of home”.

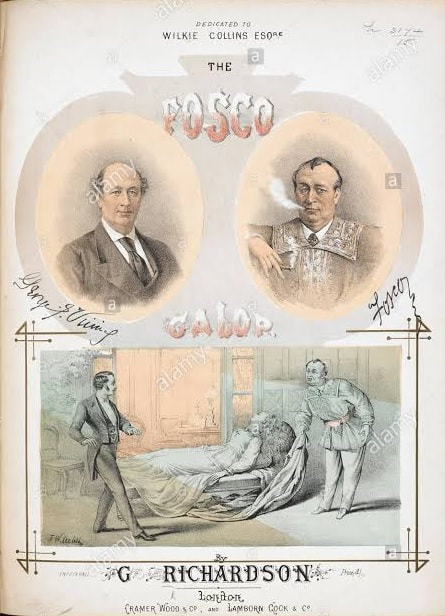

There were a number of elements that enabled Collins to achieve this. For a start, he chooses a diverse collection of larger-than-life characters – the mysterious almost ghostly woman of the title (Anne Catherick), a vulnerable wife (Laura), a scheming aristocrat (Sir Percival), an ambitious Italian count who loved white mice (Fosco), an honourable swain-turned-sleuth (Walter), an effeminate hypochondriac (Fairlie) and a "mannish" lady (Marian Halcombe) – and surrounds them with secrets, identity switches, mystery, violence, forgery, death, mental illness and passion.

His plot, intricate and labyrinthine, is itself inspired by real life ~ by sensational incidents from a French archive of criminal causes célèbre [8]; by contemporary concerns about the proper treatment of the insane, prompted by several cases of false incarceration in lunatic asylums; by the celebrated trial of Palmer the poisoner; and a disastrous scandal involving the novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton and his wife [9].

The book’s unusual structure also heightened the breathless excitement of its readers. Collins cleverly manipulated his weekly instalments by leaving readers in suspense with “cliff-hanging” moments. What would happen next became a hot dinner-table topic. Wilkie Collins himself summed it up: “Make ‘em laugh, make ‘em cry, make ‘em wait” [10]. It worked, spectacularly. During its serialisation, crowds besieged the All the Year Round offices on the day each new instalment was issued [11].

Collins’ innovative technique was also crucial. Having the story told entirely from the varying viewpoints of those involved enabled readers to have the experience of hearing an extraordinary story directly from those involved, effectively mimicking the experience of hearing “first-hand” evidence from witnesses at a criminal trial. At the same time, it introduced elements of mystery as the reader reflected on whether those accounts can actually be believed.

The book is now generally regarded as the first sensation novel, an influential genre of Victorian-era fiction – a precursor of modern genre of detective fiction -- which “fused the apprehensive thrills of Gothic literature with the psychological realism of the domestic novel” [6]. As Matthew Sweet says, “Using a high-impact style of narrative that put its characters through a series of extreme mental experiences, Collins.... brought the terrors of the Gothic novel down from mouldering Italian castles into the back parlours and drawing rooms of a recognisably modern, middle class Victorian England…. As Henry James commented, ‘to Mr Collins belongs the credit of having introduced into fiction those most mysterious mysteries of mysteries, the mysteries which are at our own doors’.” [7]. Collins himself called it “the secret theatre of home”.

There were a number of elements that enabled Collins to achieve this. For a start, he chooses a diverse collection of larger-than-life characters – the mysterious almost ghostly woman of the title (Anne Catherick), a vulnerable wife (Laura), a scheming aristocrat (Sir Percival), an ambitious Italian count who loved white mice (Fosco), an honourable swain-turned-sleuth (Walter), an effeminate hypochondriac (Fairlie) and a "mannish" lady (Marian Halcombe) – and surrounds them with secrets, identity switches, mystery, violence, forgery, death, mental illness and passion.

His plot, intricate and labyrinthine, is itself inspired by real life ~ by sensational incidents from a French archive of criminal causes célèbre [8]; by contemporary concerns about the proper treatment of the insane, prompted by several cases of false incarceration in lunatic asylums; by the celebrated trial of Palmer the poisoner; and a disastrous scandal involving the novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton and his wife [9].

The book’s unusual structure also heightened the breathless excitement of its readers. Collins cleverly manipulated his weekly instalments by leaving readers in suspense with “cliff-hanging” moments. What would happen next became a hot dinner-table topic. Wilkie Collins himself summed it up: “Make ‘em laugh, make ‘em cry, make ‘em wait” [10]. It worked, spectacularly. During its serialisation, crowds besieged the All the Year Round offices on the day each new instalment was issued [11].

Collins’ innovative technique was also crucial. Having the story told entirely from the varying viewpoints of those involved enabled readers to have the experience of hearing an extraordinary story directly from those involved, effectively mimicking the experience of hearing “first-hand” evidence from witnesses at a criminal trial. At the same time, it introduced elements of mystery as the reader reflected on whether those accounts can actually be believed.

A flurry of merchandising soon developed to cash in on the popularity of the book [12]. “Loyal fans could spray themselves with Woman in White perfume, wrap up in Woman in White cloaks and bonnets, and dance to various Woman in White waltzes and quadrilles”[13]. A stage version appeared. The poet Edward Fitzgerald considered naming his boat Marian Halcombe after “the brave girl in the story”, and “Fosco” became a favourite name for cats.

The book, and others that successfully followed it [14] were typical of a Victorian culture that was moving rapidly towards the commercialisation of pleasure. Freak shows, new types of entertainment such as elaborate technology-driven stage spectaculars, and living panoramas were becoming popular crazes. The rise of the penny press also contributed, with its voracious appetite for sensational crimes (murders, robberies, audacious fraud, poisoning) and misbehaviour (insanity, marital infidelities), often committed in domestic environments just like that of its readers [15].

In short, the book not only dealt with sensational events, but also became a sensation in itself. It was a trend that some feared had its own dangers. Critic Margaret Oliphant, for example, feared that the “violent stimulation of … weekly publication, with its necessity for frequent and rapid recurrence of piquant situation and startling incident” would lead to a degeneration of literary standards and the corruption of culture [16]. Its perceived emphasis on narrative at the expense of character, its intricately-clever plot -- “ingenious construction is not high art”, sniffed one reviewer -- and its reliance on thrills was seen “to preclude entry into the refined world of high arts” [17].

At the least, however, the success of the book provoked some critics to question the relevance of their long-held convictions. A piece in the Spectator put the question this way: “Is a landscape-painter to be condemned as incapable of high art because the figures in his picture are not…. done after the manner of Raphael or Michael Angelo?... or is there… only one style of work worthy of high esteem in any given brand of art, whether painting, poetry or literary fiction” [18]. As we shall see, this question could be applied equally to Whistler’s controversial portrait.

In short, the book not only dealt with sensational events, but also became a sensation in itself. It was a trend that some feared had its own dangers. Critic Margaret Oliphant, for example, feared that the “violent stimulation of … weekly publication, with its necessity for frequent and rapid recurrence of piquant situation and startling incident” would lead to a degeneration of literary standards and the corruption of culture [16]. Its perceived emphasis on narrative at the expense of character, its intricately-clever plot -- “ingenious construction is not high art”, sniffed one reviewer -- and its reliance on thrills was seen “to preclude entry into the refined world of high arts” [17].

At the least, however, the success of the book provoked some critics to question the relevance of their long-held convictions. A piece in the Spectator put the question this way: “Is a landscape-painter to be condemned as incapable of high art because the figures in his picture are not…. done after the manner of Raphael or Michael Angelo?... or is there… only one style of work worthy of high esteem in any given brand of art, whether painting, poetry or literary fiction” [18]. As we shall see, this question could be applied equally to Whistler’s controversial portrait.

And a challenge to propriety and identity?

While many have in the past dismissed Collins simply as a melodramatist, or mystery writer, rather than a “proper” novelist, it is certainly arguable that the book had more significant underlying themes than was initially realised. So, for example, questions of confused identity recur throughout, from the identity-switch that plays such a crucial role in the plot, to the curious range of convention-defying personality traits – an Italian who acts “English”, a young woman who acts old, an older woman who acts young; a notably masculine woman and notably effeminate man; a member of upper class who acts boorishly and a middle class character who is a ”natural” gentleman. Furthermore, those who remake their identity during the course of the story -- such as Walter transforming himself into a sleuth -- seem to make a great success of it [19].

Perhaps associated with this, it has also been suggested that the book amounts to a general challenge to the norms of Victorian propriety. Collins himself had an unconventional lifestyle, living in a ménage à trois vaguely reminiscent of the surprising living arrangements of his characters Walter, Laura and Marion. Jerome Meckier has noted how the book presents propriety as ritualistic, being unthinkingly observed as a matter of form [20]; and that the characters’ abiding concern for propriety proves to be a potent source of undesirable outcomes -- it provides opportunities for the insincere, serves as an invitation to secrecy, militates against natural enjoyment, generates major crimes to conceal less serious offences, and overtaxes the scrupulous [21]. The anomalous legal and social position of women – exemplified by Laura’s exploitation by her husband, and Anne Catherick’s forcible confinement in a mental institution – can also be seen as another form of an undesirable Victorian propriety.

Perhaps associated with this, it has also been suggested that the book amounts to a general challenge to the norms of Victorian propriety. Collins himself had an unconventional lifestyle, living in a ménage à trois vaguely reminiscent of the surprising living arrangements of his characters Walter, Laura and Marion. Jerome Meckier has noted how the book presents propriety as ritualistic, being unthinkingly observed as a matter of form [20]; and that the characters’ abiding concern for propriety proves to be a potent source of undesirable outcomes -- it provides opportunities for the insincere, serves as an invitation to secrecy, militates against natural enjoyment, generates major crimes to conceal less serious offences, and overtaxes the scrupulous [21]. The anomalous legal and social position of women – exemplified by Laura’s exploitation by her husband, and Anne Catherick’s forcible confinement in a mental institution – can also be seen as another form of an undesirable Victorian propriety.

part 2: Whistler's woman in white

The outrageous girl on the bearskin rug...

The Woman in White was the advertised name of the breakthrough painting of the American-born and Britain-based painter James McNeill Whistler. It would prove to be one of his most famous and provocative achievements.

Whistler had commenced the full-length portrait at his Paris studio in December 1861. Here is how he himself described it [22]: the model is "standing against a window which filters the light through a transparent white muslin curtain—but the figure receives a strong light from the right and therefore the picture barring the red hair is one gorgeous mass of brilliant white”.

Attired in a long white dress, she stands before a shallow white linen drapery, on what appears to be a bearskin rug, which itself lies on a Chinese carpet. Her face, while attractive, is “expressionless, and she stares vacantly off to the right, scarcely seeming to focus her eyes”. Her arms hand limply, she holds a wilted white lily in her left hand, and a scattered bouquet of purple and yellow pansies lies at her feet. Her “full red lips, dark eyes and long, unkempt red hair” -- which Whistler described as "the loveliest you've ever seen! a red that is not golden but copper” – form a contrast with the white background [23].

Whistler had commenced the full-length portrait at his Paris studio in December 1861. Here is how he himself described it [22]: the model is "standing against a window which filters the light through a transparent white muslin curtain—but the figure receives a strong light from the right and therefore the picture barring the red hair is one gorgeous mass of brilliant white”.

Attired in a long white dress, she stands before a shallow white linen drapery, on what appears to be a bearskin rug, which itself lies on a Chinese carpet. Her face, while attractive, is “expressionless, and she stares vacantly off to the right, scarcely seeming to focus her eyes”. Her arms hand limply, she holds a wilted white lily in her left hand, and a scattered bouquet of purple and yellow pansies lies at her feet. Her “full red lips, dark eyes and long, unkempt red hair” -- which Whistler described as "the loveliest you've ever seen! a red that is not golden but copper” – form a contrast with the white background [23].

The model for the painting was Joanna Hiffernan, known as Jo, who was Whistler’s lover for a number of years in the early 1860s. She also appears, rather less effectively, in Whistler’s Wapping and other paintings of that period. She has been described as "Irish, a Roman Catholic ... a woman of next-to-no education, but of keen intelligence who, before she had ceased to sit to Whistler, knew more about painting than many painters, had become well read, and had great charm of manner" [24].

Evidence suggests that Hiffernan and Whistler had a stormy relationship; in 1864 George Du Maurier reported that the artist was "in mortal fear" of her, and that she was "an awful tie" [25]. The couple parted after Whistler went to Valparaiso in 1867. Hiffernan went to Paris, where she posed for Gustave Courbet's erotic Le Sommeil [26] and, it is thought, for his even more gynaecologically-confronting Origin of the World. It is presumed that she had an affair with Courbet, but little is known of her later life.

Evidence suggests that Hiffernan and Whistler had a stormy relationship; in 1864 George Du Maurier reported that the artist was "in mortal fear" of her, and that she was "an awful tie" [25]. The couple parted after Whistler went to Valparaiso in 1867. Hiffernan went to Paris, where she posed for Gustave Courbet's erotic Le Sommeil [26] and, it is thought, for his even more gynaecologically-confronting Origin of the World. It is presumed that she had an affair with Courbet, but little is known of her later life.

... who intrigued the public

Whistler was of course aware that the work, which he originally called “The White Girl”, would cause controversy, and correctly predicted that it may well be refused by the “old duffers” at Royal Academy for their annual exhibition of 1862. He responded to their predictable rejection by exhibiting it at a private London gallery, where it was advertised as “Whistler’s Extraordinary picture The Woman in White”, an obvious allusion to Collins’ book.

As a marketing ploy, this proved a great success. The woman looked nothing like the character Anne Catherick, the “woman in white” from the book, but some critics – in the absence of any indication by Whistler of the model’s identity or marital status -- assumed that she was intended to, and criticised the painting on that account. The critic/painter Frederick George Stephens, for example, described it as a “bizarre production” because “the face is well done, but it is not that of Mr Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White” [27].

Whistler responded vigorously that he "had no intention whatsoever of illustrating Mr. Wilkie Collins's novel; it so happens, indeed that I have never read it. My painting simply represents a girl dressed in white standing in front of a white curtain". He claimed that the renaming was entirely the gallery owner’s idea, though it seems clear that he was more than happy content to accede to it and was almost certainly aware of how the connection could benefit him. Privately, he gleefully wrote that the painting is “affiched [postered] all over town” with sandwich board men advertising “Whistler’s Extraordinary picture THE WOMAN IN WHITE” [28].

This sort of vigorous promotion of paintings had become quite popular at the time, with a number of artists publicising their works as entertainment. For example, William Powell Frith’s extensively-promoted panoramic painting The Railway Station attracted more than 21,000 people in the seven weeks in which it was on public display. It was a particularly effective blurring of elements from both high and low culture [29].

Whistler later submitted the painting at the Paris Salon of 1863 and, when rejected there, at the Salon des Refusés, where it again created a sensation, even rivalling that of Manet’s notorious Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, which was in the same exhibition. Emile Zola noted that "folk nudged each other and went almost into hysterics; there was always a grinning group in front of it"[30].

As a marketing ploy, this proved a great success. The woman looked nothing like the character Anne Catherick, the “woman in white” from the book, but some critics – in the absence of any indication by Whistler of the model’s identity or marital status -- assumed that she was intended to, and criticised the painting on that account. The critic/painter Frederick George Stephens, for example, described it as a “bizarre production” because “the face is well done, but it is not that of Mr Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White” [27].

Whistler responded vigorously that he "had no intention whatsoever of illustrating Mr. Wilkie Collins's novel; it so happens, indeed that I have never read it. My painting simply represents a girl dressed in white standing in front of a white curtain". He claimed that the renaming was entirely the gallery owner’s idea, though it seems clear that he was more than happy content to accede to it and was almost certainly aware of how the connection could benefit him. Privately, he gleefully wrote that the painting is “affiched [postered] all over town” with sandwich board men advertising “Whistler’s Extraordinary picture THE WOMAN IN WHITE” [28].

This sort of vigorous promotion of paintings had become quite popular at the time, with a number of artists publicising their works as entertainment. For example, William Powell Frith’s extensively-promoted panoramic painting The Railway Station attracted more than 21,000 people in the seven weeks in which it was on public display. It was a particularly effective blurring of elements from both high and low culture [29].

Whistler later submitted the painting at the Paris Salon of 1863 and, when rejected there, at the Salon des Refusés, where it again created a sensation, even rivalling that of Manet’s notorious Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, which was in the same exhibition. Emile Zola noted that "folk nudged each other and went almost into hysterics; there was always a grinning group in front of it"[30].

... and confused the critics

Part of the sensation generated by the painting arose from the baffled and often hostile reaction of many critics. Objections to the painting were raised on a number of grounds. So, critics noted that the paint was applied unevenly – thinner over the face than the background – and the artist’s brushstrokes were clearly visible. The painting also ignored accepted rules of perspective -- the floor appeared to be slanting toward the viewer and there was little depth. All these features were seen as running counter to the normal conventions and expectations of “high art”.

The casual blankness of the woman also raised issues. She just wasn’t ladylike. One American reviewer in the Art Journal, struggling to reconcile a feeling of distaste with a degree of reluctant admiration, noted [31]:

“It represents, on a background formed by a white curtain, the full-length figure of a young girl, attired in an anomalous white garment, which hangs upon her person in absolute defiance of all ordinary canons of good taste. Her attitude, also, is devoid of all feminine grace, and the effect of the whole is extremely stiff and unlife-like. Yet the face is attractive and even fascinating, and the long, dishevelled hair approaches to that pure golden brown hue the great Venetian masters loved to paint; while the whole picture, on closer acquaintance, loses much of its first unpleasing effect. But it cannot be doubted that mannerisms which have the appearance of affectation are not in unison with the spirit of true art”.

The casual blankness of the woman also raised issues. She just wasn’t ladylike. One American reviewer in the Art Journal, struggling to reconcile a feeling of distaste with a degree of reluctant admiration, noted [31]:

“It represents, on a background formed by a white curtain, the full-length figure of a young girl, attired in an anomalous white garment, which hangs upon her person in absolute defiance of all ordinary canons of good taste. Her attitude, also, is devoid of all feminine grace, and the effect of the whole is extremely stiff and unlife-like. Yet the face is attractive and even fascinating, and the long, dishevelled hair approaches to that pure golden brown hue the great Venetian masters loved to paint; while the whole picture, on closer acquaintance, loses much of its first unpleasing effect. But it cannot be doubted that mannerisms which have the appearance of affectation are not in unison with the spirit of true art”.

Another reviewer [32] described the painting as representing "a powerful female with red hair, and a vacant stare in her soulless eyes...The picture evidently means vastly more than it expresses—albeit expressing too much. Notwithstanding an obvious want of purpose, there is some boldness in the handling and a singularity in the glare of the colours which cannot fail to divert the eye, and to weary it”.

What particularly irritated or even befuddled many critics at the time was simply that the painting did not seem to be “about” anything. It did not tell a story, it was not a study of nature, it did not fall into any recognisable genre, and was not a portrait of a rich or famous person. The woman was not looking at anything, was not doing anything, and had no discernible expression. People were simply not familiar with this sort of painting.

In this respect, the painting can usefully be compared to Charles Joshua Chaplin’s Reflection, painted in traditional style at about the same time, which similarly features a woman in a white dress standing against a rather plain background, shares a similar pale palette of colours to Whistler’s, and even has some discarded blossoms on the floor, as Whistler’s painting does. But the artist here has provided us with a number of additional clues about what’s going on. For example, the double-meaning title reminds us that the woman is both reflecting about something, and also looking at her physical reflection in the mirror. We can judge from the room furnishings, the woman’s shoes and dress, and the prim way she holds the posy of flowers, that she comes from a respectable background. Her expression, a mixture of a demure simper and a hint of the coquette, can guide us in interpreting what she is reflecting on. And so on. By contrast, Whistler’s woman and her surroundings tell us virtually nothing.

What particularly irritated or even befuddled many critics at the time was simply that the painting did not seem to be “about” anything. It did not tell a story, it was not a study of nature, it did not fall into any recognisable genre, and was not a portrait of a rich or famous person. The woman was not looking at anything, was not doing anything, and had no discernible expression. People were simply not familiar with this sort of painting.

In this respect, the painting can usefully be compared to Charles Joshua Chaplin’s Reflection, painted in traditional style at about the same time, which similarly features a woman in a white dress standing against a rather plain background, shares a similar pale palette of colours to Whistler’s, and even has some discarded blossoms on the floor, as Whistler’s painting does. But the artist here has provided us with a number of additional clues about what’s going on. For example, the double-meaning title reminds us that the woman is both reflecting about something, and also looking at her physical reflection in the mirror. We can judge from the room furnishings, the woman’s shoes and dress, and the prim way she holds the posy of flowers, that she comes from a respectable background. Her expression, a mixture of a demure simper and a hint of the coquette, can guide us in interpreting what she is reflecting on. And so on. By contrast, Whistler’s woman and her surroundings tell us virtually nothing.

This blankness left many critics floundering. One anonymous critic in the Athenaeum [33] objected that “it is one of the most incomplete paintings we ever met with. A woman, in a quaint morning dress of white, with her hair about her shoulders stands alone, in a background of nothing in particular..” Other critics, understandably, attempted to discern their own narrative in the work, producing mutually-contradictory interpretations which simply amounted to speculation. Not surprisingly, these tended to involve sexuality in some way, as they attempted to fill the vacuum deliberately left by a painting in which the artist has avoided any specific commitment to its sexual connotations [34]. The contrast between the woman’s chaste white dress and the rampant animality of the bearskin she is standing on (in bare feet, no doubt!) was enough to agitate most male critics’ fertile imaginations. So, the woman was variously interpreted as a young bride confronting the loss of her virginity on the morning after her bridal night (with deflowering signified by the dropped blossoms); or as a sexless spiritual medium; or as a courtesan or wanton woman.

The point that these critics failed to grasp was simply that there was no point. Whistler considered that the painting was just a representation of a model standing in a studio, and nothing more. Its appeal was purely to the eye, and those who tried to provide it with a narrative context were simply misguided [35]. It was not, as one critic said, an “inaccessible riddle”. It was “art for art’s sake”, an arrangement of colour, pattern and texture, a concept which became explicit in the retitling of the work to Symphony in White No 1 [36].

conclusion

In addition to their similar titles and launch dates, Collins’ and Whistler’s works both created a sensation, both involved a mystery and both challenged society’s expectations of legitimate “art”. But alongside these undoubted similarities, there are also fundamental differences. Collins’ book caused a sensation because of its constant revelations, and its astonishing popularity, whereas Whistler’s painting caused a sensation because it was daring and seemingly inexplicable. While Collins said that the “primary object of a work of fiction should be to tell a story”, Whistler insisted that there was no “story” at all in his painting and it simply represented what it depicted. And while Collins invited his readers to immerse themselves in the lives and fates of the characters in his book, Whistler positively discouraged his viewers from seeking to identify with the person that he had depicted.

Two women in white – and two remarkably different ways to achieve creative success.

© Philip McCouat, 2020. First published January 2020.

This article may be cited as “Philip McCouat, “The Two Women in White”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

Two women in white – and two remarkably different ways to achieve creative success.

© Philip McCouat, 2020. First published January 2020.

This article may be cited as “Philip McCouat, “The Two Women in White”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

End notes

[1] Robert Wilson Torchia et al, ‘American Paintings of the Nineteenth Century: Pt II’, Catalogue of National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1998, at 243 https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/research/publications/pdfs/American%20Paintings%20of%20the%20Nineteenth%20Century%20Part%20II.pdf

[2] Also known as The White Girl, and later retitled by Whistler as Symphony in White, No 1

[3] Jon Michael Varese, “The Woman in White's 150 years of sensation” (Guardian, 26 November 2009). In the United States, the novel was published serially in Harper’s Weekly

[4] John Sutherland, ed, “Introduction” to Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White, Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford, 1996

[5] Sutherland, op cit

[6] Matthew Sweet, ed, “Introduction” to Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White, Penguin Books, London 1999 at xiii

[7] Sweet. op cit

[8] Sweet, op cit at xxiii

[9] Sutherland, op cit

[10] This quote has also been variously attributed, including to fellow sensation novelist Charles Reade

[11] Sweet, op cit at xvi; Kenneth Robinson, Wilkie Collins: A Biography, Davis Poynter, London, 1974

[12] Sweet, op cit at xv

[13] Robinson, op cit

[14] Such as Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret (1862) and Ellen Wood’s East Lynne (1861)

[15] Sweet, op cit at xiv

[16] Cited in Sweet, op cit at xvii

[17] Rachel Teukolsky, “White Girls: Avant-Gardism and Advertising after 1860”, Victorian Studies, vol 51, No 3, 422, at 434, 432

[18] Teukolsky, op cit

[19] Dallas Liddle, “Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White (1859–60).” Victorian Review, vol. 35, no. 1, 2009, pp. 37–41

[20] Jerome Meckier, "Wilkie Collins's the Woman in White: Providence against the Evils of Propriety," Journal of British Studies 22, no. 1 (1982): 104-26, at 107. Accessed January 13, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/175659

[21] Meckier, op cit at 109

[22] Robert Wilson Torchia et al, ‘American Paintings of the Nineteenth Century: Pt II’, Catalogue of National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1998, p 232, at 239 https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/research/publications/pdfs/American%20Paintings%20of%20the%20Nineteenth%20Century%20Part%20II.pdf

[23] Torchia, op cit at 240

[24] Elizabeth and Joseph Pennell, The Whistler Journal, Philadelphia 1921, cited in Torchia, op cit

[25] Cited in Torchia, op cit at 239

[26] Musée du Petit Palais, Paris. This painting, of lesbian lovers, was considered so shocking that it

was not publicly displayed for decades

[27] Torchia, op cit at 240

[28] Teukolsky, op cit at 426-7

[29] Teukolsky, op cit at 427

[30] Torchia, op cit at 240

[31] Torchia, op cit at 243

[32] Torchia, op cit at 242

[33] Torchia, op cit at 240

[34] Robin Spencer, Whistler, Studio Editions, London 1992 at 52

[35] Torchia, op cit at 241

[36] The concept of “art for art’s sake” is associated with the writings of the French poet and art critic Théophile Gautier, who expounded his aesthetic theory in the novel Mlle de Maupin (1834) and the poem Symphonie en blanc majeur: Torchia, op cit at 242.

© Philip McCouat, 2020. First published January 2020.

This article may be cited as “Philip McCouat, “The Two Women in White”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

[2] Also known as The White Girl, and later retitled by Whistler as Symphony in White, No 1

[3] Jon Michael Varese, “The Woman in White's 150 years of sensation” (Guardian, 26 November 2009). In the United States, the novel was published serially in Harper’s Weekly

[4] John Sutherland, ed, “Introduction” to Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White, Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford, 1996

[5] Sutherland, op cit

[6] Matthew Sweet, ed, “Introduction” to Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White, Penguin Books, London 1999 at xiii

[7] Sweet. op cit

[8] Sweet, op cit at xxiii

[9] Sutherland, op cit

[10] This quote has also been variously attributed, including to fellow sensation novelist Charles Reade

[11] Sweet, op cit at xvi; Kenneth Robinson, Wilkie Collins: A Biography, Davis Poynter, London, 1974

[12] Sweet, op cit at xv

[13] Robinson, op cit

[14] Such as Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret (1862) and Ellen Wood’s East Lynne (1861)

[15] Sweet, op cit at xiv

[16] Cited in Sweet, op cit at xvii

[17] Rachel Teukolsky, “White Girls: Avant-Gardism and Advertising after 1860”, Victorian Studies, vol 51, No 3, 422, at 434, 432

[18] Teukolsky, op cit

[19] Dallas Liddle, “Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White (1859–60).” Victorian Review, vol. 35, no. 1, 2009, pp. 37–41

[20] Jerome Meckier, "Wilkie Collins's the Woman in White: Providence against the Evils of Propriety," Journal of British Studies 22, no. 1 (1982): 104-26, at 107. Accessed January 13, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/175659

[21] Meckier, op cit at 109

[22] Robert Wilson Torchia et al, ‘American Paintings of the Nineteenth Century: Pt II’, Catalogue of National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1998, p 232, at 239 https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/research/publications/pdfs/American%20Paintings%20of%20the%20Nineteenth%20Century%20Part%20II.pdf

[23] Torchia, op cit at 240

[24] Elizabeth and Joseph Pennell, The Whistler Journal, Philadelphia 1921, cited in Torchia, op cit

[25] Cited in Torchia, op cit at 239

[26] Musée du Petit Palais, Paris. This painting, of lesbian lovers, was considered so shocking that it

was not publicly displayed for decades

[27] Torchia, op cit at 240

[28] Teukolsky, op cit at 426-7

[29] Teukolsky, op cit at 427

[30] Torchia, op cit at 240

[31] Torchia, op cit at 243

[32] Torchia, op cit at 242

[33] Torchia, op cit at 240

[34] Robin Spencer, Whistler, Studio Editions, London 1992 at 52

[35] Torchia, op cit at 241

[36] The concept of “art for art’s sake” is associated with the writings of the French poet and art critic Théophile Gautier, who expounded his aesthetic theory in the novel Mlle de Maupin (1834) and the poem Symphonie en blanc majeur: Torchia, op cit at 242.

© Philip McCouat, 2020. First published January 2020.

This article may be cited as “Philip McCouat, “The Two Women in White”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com