Carpaccio’s double enigma

Hunting on the Lagoon and the Two Venetian Ladies

By Philip McCouat For comments on this article, see here

Part 1: a 500 year puzzle

A little over 500 years ago, the Venetian painter Vittore Carpaccio, regarded as second only to Bellini as the outstanding Venetian painter of his generation [1], created two striking scenes of his native city. One of them would later be described as the most wonderful painting in the world. The other would end up in a junk shop. Just exactly what either of them depicts has continued to divide opinion to the present day. And the mystery has only deepened with the discovery that although the pictures show different characters, different activities and different settings, they are actually both parts of a single painting. This is their story….

A painting of two halves (or more)

One of the scenes, Two Venetian Ladies, has been known for centuries and is currently held in the Correr Museum in Venice. The other scene, Hunting on the Lagoon, did not surface to public view until 1944 and is held on the other side of the world, at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

In 1961, the art scholar Giles Robertson made the bold claim that the two paintings had originally formed one long vertical panel, with Hunting on top and Two Ladies on the base, and that they had been separated at some time in the past [2].

A painting of two halves (or more)

One of the scenes, Two Venetian Ladies, has been known for centuries and is currently held in the Correr Museum in Venice. The other scene, Hunting on the Lagoon, did not surface to public view until 1944 and is held on the other side of the world, at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

In 1961, the art scholar Giles Robertson made the bold claim that the two paintings had originally formed one long vertical panel, with Hunting on top and Two Ladies on the base, and that they had been separated at some time in the past [2].

|

His view was based largely on the chopped-off appearance of the bunch of lilies in the vase which stands on the balcony of the terrace at the left in Two Ladies. Robertson noticed that the corresponding top of a bunch of lilies re-appears in the bottom left of Hunting. When the two paintings are lined up (Fig 1), the continuity appears perfect. The combined painting can then be seen to be depicting two women on a terrace which overlooks the lagoon where the men are hunting.

Initially, this suggestion did not met with universal approval. Robertson himself withdrew it shortly after he had made it, and indeed it seemed incongruous to have a palazzo terrace situated out in the backblocks of the lagoon [3]. However, the correctness of the suggestion has subsequently been confirmed through an extensive program of cleaning and testing, including a detailed comparison of perspective lines and the woodgrain patterns of the bottom edge of Hunting and the top edge of Two Ladies [4]. In the face of this, the joinder of the two panels, previously considered to be an unlikely mix of indoor and outdoor scenes, has now somehow been transformed into a positive, with Knauer commenting that “one cannot but admire the daring juxtaposition” of an intimate close-up interior scene and a distant outdoor view of the boats [5]. |

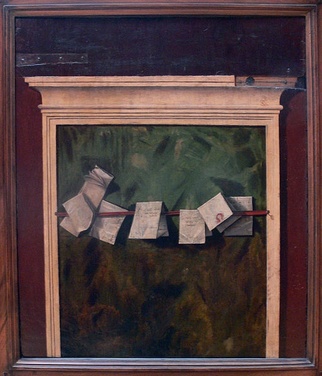

This however, is not the end of the surprises. On the reverse (verso) of Hunting is yet another painting (Fig 2), which has nothing at all to do with the subject matter of the front (recto). This painting on the reverse gives the illusion of a marble niche framing a series of letters hung on a cord which is nailed to the inside of the frame. George Goldner describes this “fresh and novel creation” as the first trompe l’oeil (deceive the eye) rendering of its kind in Italian painting since antiquity [6]. One of the documents there apparently bears the name of Andrea Mocenigo who possibly commissioned the entire work.

You want more? Indentations on both edges of each of the main panels indicate that they were once horizontally joined to two other panels, which have presumably been lost (check your attics!). In other words, the combined painting that you see in Fig 1, about 170 cms high, and 64 cm wide, is just the right-hand side of a shutter or door which would have bended vertically in the middle, with the left-hand panels presumably being continuation of the existing right-hand panels. This conclusion is supported by the radical chopping of the left hand side of Two Ladies , which decapitates the large dog and leaves the ladies looking at nothing; and by the tiny indication, on the extreme left-hand edge of Hunting, of the nose and clenched hand of the steersman who must be standing in the unseen stern of the boat. This is best appreciated by consulting the Getty Museum's high-resolution image (highly recommended).

The mechanics of how this works are best demonstrated in a separateGetty Museum video. The overall intended effect of the entire work was to play two pleasing tricks on a viewer. The first was that when both sides are closed, the viewer who was in a closed room was given a convincing impression that they were instead standing on the airy terrace occupied by the two ladies, and looking out beyond to see a picturesque view of the lagoon. On the other hand, when the doors are fully opened, the viewer sees instead the extremely convincing trompe l’oeil notice board/letter rack, seemingly attached to the wall behind it.

The oddness and incompleteness of the existing panels does not stop there, but also extends to their actual subject matter. Who exactly are these people, and what exactly are they supposed to be doing? It is to this issue that we now turn.

The mechanics of how this works are best demonstrated in a separate

The oddness and incompleteness of the existing panels does not stop there, but also extends to their actual subject matter. Who exactly are these people, and what exactly are they supposed to be doing? It is to this issue that we now turn.

Pt 2: Hunting on the Lagoon

Hunting cormorants for plumage or sport?

Although recorded from at least the nineteenth century, Hunting on the Lagoon (Fig 3) -- the top part of our composite -- only came to public prominence in 1944, when Andrea Busiri-Vici came across it, unrecognized, unloved and dirty, in the shop of a Roman antiquarian [7].

Although recorded from at least the nineteenth century, Hunting on the Lagoon (Fig 3) -- the top part of our composite -- only came to public prominence in 1944, when Andrea Busiri-Vici came across it, unrecognized, unloved and dirty, in the shop of a Roman antiquarian [7].

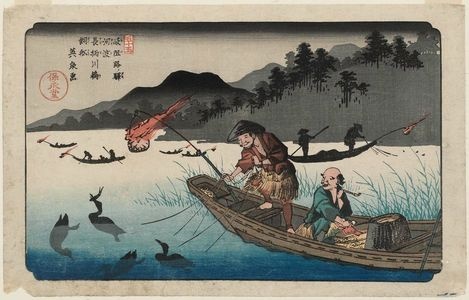

The painting depicts a number of hunting groups standing on narrow shallow-bottomed boats in the Venetian Lagoon. Each boat is being steered from the stern by one man, and poled along by two other men, with a separate archer on the prow who is either firing at something in the water, or is in readiness to do so. The fact that they are hunting in this closed area [7A], the presence of Moorish steersmen (possibly servants [8]), and the expensive clothing of all the participants indicate that this is a patrician activity, with the actual hunting being carried out by noblemen [9]. A number of water birds are swimming, diving or sitting on fences or posts, and a single dark bird also appears sitting inconspicuously on the gunwale of each boat.

Most of the immediate action is taking place on the three boats in the foreground. The first thing to note is that the archers are not firing arrows as you might assume. Instead, they are firing pellets [pallottole]. If you access the excellent high-resolution image provided by the Getty Museum, you can see one of these in mid-air, just inches away from the head of the closest water bird. Reserve supplies of pellets, supposedly made of terracotta, are contained in the baskets that appear on the bow seats of each of the boats.

The most straightforward explanation for all this activity is that the men are hunting cormorants (Fig 4) for their highly-valued plumage [10]. On this view, pellets are being used instead of arrows so that the plumage will not be damaged [11].

Most of the immediate action is taking place on the three boats in the foreground. The first thing to note is that the archers are not firing arrows as you might assume. Instead, they are firing pellets [pallottole]. If you access the excellent high-resolution image provided by the Getty Museum, you can see one of these in mid-air, just inches away from the head of the closest water bird. Reserve supplies of pellets, supposedly made of terracotta, are contained in the baskets that appear on the bow seats of each of the boats.

The most straightforward explanation for all this activity is that the men are hunting cormorants (Fig 4) for their highly-valued plumage [10]. On this view, pellets are being used instead of arrows so that the plumage will not be damaged [11].

|

There is certainly documentary evidence that water bird hunting using pellets went on in Venice. Writing in 1555, the French naturalist Pierre Belon described how noblemen, especially in the neighborhood of Venice, enjoyed sending out a flotilla of very light boats, rowed by 5 or 6 men, firing at cormorants with pellet bows whenever the birds put their heads above water.

|

These birds therefore never got the chance to take off in flight and, after repeatedly diving to the point of suffocation, were eventually taken out exhausted by their pursuers [12]. This description tallies remarkably well with the scene evidently depicted by Carpaccio.

A similar scenario is described by James Howell, writing somewhat later, in 1651 [13].

“The pleasures, recreations and pastimes of the [Venetian] Gentlemen are of divers kinds, among the rest they take great delight in Fowling, making great matches who can kill most Fowle in a day, turning till the end thereof to banqueting and pleasure. They have Boats of purpose calld Fisolari so nam'd from Fisolo, which is the name of the Bird they seek after; In every of these Boates they have six or eight servants …[who] row the Boat up and down, turning her suddenly to every side as they are commanded by their Master, who sits close with his Peece [gun] or Bow wholly attentive upon his sport; If he chance to misse when he shooteth, the Fisolo dives under water, and where he riseth again thither they turn their Boats with much nimble∣ness… Upon their return they hang the Fowle they have killed out of the Window, as Hunters do upon their Doors the heads of Beares, Bores, Hares, taking it as a great reputation to kill more of these in a day than their fellowes can.”

It will be noted, however, that neither Belon nor Howell make any mention of hunting the birds for their plumage. Belon does not mention whether there was any particular purpose in the hunting, and Howell essentially suggests that it was being carried out for mere “sport” and bragging rights. It also needs to be appreciated that the use of pellets does not necessarily indicate that the obtaining of plumage is the purpose – putting questions of plumage aside, using pellets simply enables there to be a clean kill without tearing the flesh.

A similar scenario is described by James Howell, writing somewhat later, in 1651 [13].

“The pleasures, recreations and pastimes of the [Venetian] Gentlemen are of divers kinds, among the rest they take great delight in Fowling, making great matches who can kill most Fowle in a day, turning till the end thereof to banqueting and pleasure. They have Boats of purpose calld Fisolari so nam'd from Fisolo, which is the name of the Bird they seek after; In every of these Boates they have six or eight servants …[who] row the Boat up and down, turning her suddenly to every side as they are commanded by their Master, who sits close with his Peece [gun] or Bow wholly attentive upon his sport; If he chance to misse when he shooteth, the Fisolo dives under water, and where he riseth again thither they turn their Boats with much nimble∣ness… Upon their return they hang the Fowle they have killed out of the Window, as Hunters do upon their Doors the heads of Beares, Bores, Hares, taking it as a great reputation to kill more of these in a day than their fellowes can.”

It will be noted, however, that neither Belon nor Howell make any mention of hunting the birds for their plumage. Belon does not mention whether there was any particular purpose in the hunting, and Howell essentially suggests that it was being carried out for mere “sport” and bragging rights. It also needs to be appreciated that the use of pellets does not necessarily indicate that the obtaining of plumage is the purpose – putting questions of plumage aside, using pellets simply enables there to be a clean kill without tearing the flesh.

|

There are, of course, a number of other possible reasons for hunting, such as hunting the birds for food or hunting to eradicate them as pests. We can probably rule out the first of these if the birds are cormorants, as the Getty Museum believes. Cormorants are not generally regarded as game birds; they are often described as inedible [14], or as suitable only for the “lower classes” [15], or even as food fit for the devil [16]. Similarly, in his History of Birds, the Count de Buffon writes that the cormorant has a very strong smell and an unpleasant taste, “though it is not always despised by sailors, to whom the simplest and coarsest fare is often more delicious than the most exquisite viands to our delicate palates” [17]. In short, one way or the other, cormorant does not appear to be suitable fare for noblemen.

A slightly more likely possibility would be that the cormorants were being hunted because they were pests. Cormorants are notorious for their voracious appetites for fish, and for centuries right up to the present day have incurred the wrath of humans who feel that they are depleting fish stocks [18]. There are references going back as far as the thirteenth century to the cormorants’ “injurious” effects on the fish fauna. |

-----------------------------------------

Carpaccio you definitely can eat The Venetian raw meat dish that we know as carpaccio is named after the painter Vittore Carpaccio, supposedly because of his characteristic use of brilliant reds and whites. Guiseppe Cipriani, the founder of Harry’s Bar, invented the dish in 1950, the year of the great Carpaccio exhibition in Venice. He was responding to a request by the Contessa Amalia Mocenigo, a frequent customer, whose doctor had placed her on diet forbidding cooked meat. (Coincidentally, she had the same surname as the “Mocenigo” which appears in the trompe l’oeil letter rack on the reverse of Hunters.) In its classical form, the dish consists of very thin slices of dressed raw beef, typically with cheese shavings and a crisscross pattern of cream-coloured sauce made from mayonnaise, Worcestershire sauce, lemon juice and milk [19]. The concept has since been expanded to all sorts of meat or fish or vegetables, even kangaroo, with veal carpaccio reputedly being used as padding for uncomfortable shoes of dancers at the Folies Bergère! [20]. ------------------------------------------------------ |

Problems with the “hunting cormorants” scenario

No matter what the purpose of the hunting is, the “hunting cormorants” scenario has some difficulties. The first of these concerns the corpses draped over the gunwales of the boat at left, and on the more distant boat in the background. The theory would require that these corpses are must be of cormorants, presumably lying on their backs, with their long necks and heads trailing in the water. However, even though some species of cormorant have substantially white breasts, the almost total whiteness of these corpses forms a stark contrast to the almost entirely black plumage of the other birds depicted in the painting. Are they corpses of some other type of bird?

The second possible objection is the apparent disinterest and lack of alarm shown by the (undoubted) cormorants who are sitting on the gunwales of the boats. Why are they not showing natural distress or fear at the killing of their fellow species right in front of them? One explanation for this might be that the sitting birds are not actually real birds at all, but artificial decoys, commonly used in hunting to attract other birds [21]. This impression is supported by these birds’ total lack of animation, their almost uniform black colour, the lack of differentiation in their features or plumage and the fact that there is no more than one on each boat [22].

The third and most puzzling objection to the “hunting cormorants” interpretation concerns the mini-scene depicted on the right edge of the reed island in the background. If you go to the high-resolution Getty image, you will see a type of open-air pen enclosing half a dozen black and white birds, possibly pied cormorants. Why would they be kept like this, and why don’t they fly away? One obvious explanation is that they are tame, have had their wings clipped or are restrained in some way, possibly by a cord attached to a post. But why are some cormorants tamed and restrained but other cormorants hunted and killed?

All of these objections prompt us to consider an alternative explanation -- an entirely different interpretation of what is going on. It is to this that we now turn.

Using cormorants to hunt fish?

Elfriede Knauer has argued that the men are not hunting the cormorants at all, but are simply using them to hunt for fish. This technique, which has been used in China and Japan for many centuries, exploits the cormorants’ tameability, voracious appetite and advanced fishing skills [23].

The technique involves catching (or breeding) the cormorants, taming them, and then training them to catch fish and return them to their masters. Typically, a ring or noose would be attached round the birds’ throats which would enable them to swallow minnows, but prevent them from swallowing the desirable larger fish, which they would disgorge on their master’s signal. While being trained they would typically have a cord attached to one leg to prevent them escaping altogether. Once they had reached a particular level, the cord and sometimes even the ring might be dispensed with [24]. Vivid descriptions of cormorant fishing as practised in China actually appeared quite early in Europe, such as in the writings of Odoric of Pordenone (1263-1331), a Franciscan missionary who had travelled widely.

No matter what the purpose of the hunting is, the “hunting cormorants” scenario has some difficulties. The first of these concerns the corpses draped over the gunwales of the boat at left, and on the more distant boat in the background. The theory would require that these corpses are must be of cormorants, presumably lying on their backs, with their long necks and heads trailing in the water. However, even though some species of cormorant have substantially white breasts, the almost total whiteness of these corpses forms a stark contrast to the almost entirely black plumage of the other birds depicted in the painting. Are they corpses of some other type of bird?

The second possible objection is the apparent disinterest and lack of alarm shown by the (undoubted) cormorants who are sitting on the gunwales of the boats. Why are they not showing natural distress or fear at the killing of their fellow species right in front of them? One explanation for this might be that the sitting birds are not actually real birds at all, but artificial decoys, commonly used in hunting to attract other birds [21]. This impression is supported by these birds’ total lack of animation, their almost uniform black colour, the lack of differentiation in their features or plumage and the fact that there is no more than one on each boat [22].

The third and most puzzling objection to the “hunting cormorants” interpretation concerns the mini-scene depicted on the right edge of the reed island in the background. If you go to the high-resolution Getty image, you will see a type of open-air pen enclosing half a dozen black and white birds, possibly pied cormorants. Why would they be kept like this, and why don’t they fly away? One obvious explanation is that they are tame, have had their wings clipped or are restrained in some way, possibly by a cord attached to a post. But why are some cormorants tamed and restrained but other cormorants hunted and killed?

All of these objections prompt us to consider an alternative explanation -- an entirely different interpretation of what is going on. It is to this that we now turn.

Using cormorants to hunt fish?

Elfriede Knauer has argued that the men are not hunting the cormorants at all, but are simply using them to hunt for fish. This technique, which has been used in China and Japan for many centuries, exploits the cormorants’ tameability, voracious appetite and advanced fishing skills [23].

The technique involves catching (or breeding) the cormorants, taming them, and then training them to catch fish and return them to their masters. Typically, a ring or noose would be attached round the birds’ throats which would enable them to swallow minnows, but prevent them from swallowing the desirable larger fish, which they would disgorge on their master’s signal. While being trained they would typically have a cord attached to one leg to prevent them escaping altogether. Once they had reached a particular level, the cord and sometimes even the ring might be dispensed with [24]. Vivid descriptions of cormorant fishing as practised in China actually appeared quite early in Europe, such as in the writings of Odoric of Pordenone (1263-1331), a Franciscan missionary who had travelled widely.

Knauer suggests that Hunting is “unique visual testimony” to this sport’s popularity in renaissance Venice and that it was very probably already current there by the fourteenth century, centuries before its adoption in Holland, England or France. If accepted, this theory is quite significant, as it elevates the painting to an historical document evidencing an important east-west cultural exchange. This would particularly befit Venice, given its role as a geographical and cultural crossroads. The theory also has the advantage of explaining the presence of the cormorants standing on the gunwales (in China this was a standard position for diving in) and also explains the presence of the penned birds on the reed island [25].

The use of “tame diving birds” used in Venice to catch fish was mentioned as early as 1557 [26]. Knauer also claims that there is other evidence of cormorant fishing in art works such as the painting by Longhi shown at Fig 6. However, this is questionable. Longhi’s archer is clearly not cormorant fishing – his bow is aimed in the air, and on close examination, there appear to be dead white birds with wings outstretched on the seats in the boat.

The use of “tame diving birds” used in Venice to catch fish was mentioned as early as 1557 [26]. Knauer also claims that there is other evidence of cormorant fishing in art works such as the painting by Longhi shown at Fig 6. However, this is questionable. Longhi’s archer is clearly not cormorant fishing – his bow is aimed in the air, and on close examination, there appear to be dead white birds with wings outstretched on the seats in the boat.

Furthermore, if Carpaccio’s birds were in fact being used for fishing, as Knauer argues, why are the men firing pellets at them? Knauer suggests that the pellets act as a friendly reminder to the birds that they should disgorge their fish. She concedes that this procedure is “somewhat convoluted”, but seeks to explain it on the basis that it is some sort of noble embellishment, peculiar to Venice. But, in any event, one would imagine that a solid clay pellet fired at point blank range at a bird’s head would not just be a reminder – it would be far more likely to kill or knock the bird senseless, as Howell describes. One might also feel that if the birds are so well trained that they do not require rings around their neck, they would also be proficient enough not to require being shot at in order to remind them of their duties [27].

A further objection to the fishing scenario is the seemingly obvious point that the bird in the foreground of Hunting, which is about to be “reminded’ by being fired at, simply does not have any fish in its throat to disgorge. So why fire at it? Do we need to postulate instead that the pellet is not intended to be a reminder to disgorge a fish, but rather to get the bird diving in the first place?

Even if these objections can be resolved, we are still faced with yet another. This concerns the identity of the corpses lying on the gunwales of the closest boat on the left [28]. Knauer’s theory obviously cannot work if these are birds. Instead, she states that they are gutted “silvery white” corpses of fish caught by the cormorants. In practical terms, it must be said that this would be an odd way to transport dead fish, and not just because they are likely to slip off. Normally, a newly-caught fish is placed in water to keep it fresh and to prevent it from drying out while the hunt continues [29].

In any event, while perceptions are obviously subjective, I just cannot convince myself that these objects are actually fish. Their “heads” are curiously undifferentiated and look more like the underside of birds, and their “tails” are extraordinarily elongated and thin. Furthermore, on the Getty’s high–resolution image, one can discern what is arguably a bird’s head on the underwater “tail” of the closest corpse. To me, this applies even more so to the corpses on the other boat further out in the lagoon, and this impression is heightened by a 1610 print by Giacomo Franco of a very similar scene, where the corpses lying over the gunwales are clearly those of birds; and the similar situation (though the archer is now a gunman) depicted in a 1594 print by Bertelli (Fig 7) [30].

A further objection to the fishing scenario is the seemingly obvious point that the bird in the foreground of Hunting, which is about to be “reminded’ by being fired at, simply does not have any fish in its throat to disgorge. So why fire at it? Do we need to postulate instead that the pellet is not intended to be a reminder to disgorge a fish, but rather to get the bird diving in the first place?

Even if these objections can be resolved, we are still faced with yet another. This concerns the identity of the corpses lying on the gunwales of the closest boat on the left [28]. Knauer’s theory obviously cannot work if these are birds. Instead, she states that they are gutted “silvery white” corpses of fish caught by the cormorants. In practical terms, it must be said that this would be an odd way to transport dead fish, and not just because they are likely to slip off. Normally, a newly-caught fish is placed in water to keep it fresh and to prevent it from drying out while the hunt continues [29].

In any event, while perceptions are obviously subjective, I just cannot convince myself that these objects are actually fish. Their “heads” are curiously undifferentiated and look more like the underside of birds, and their “tails” are extraordinarily elongated and thin. Furthermore, on the Getty’s high–resolution image, one can discern what is arguably a bird’s head on the underwater “tail” of the closest corpse. To me, this applies even more so to the corpses on the other boat further out in the lagoon, and this impression is heightened by a 1610 print by Giacomo Franco of a very similar scene, where the corpses lying over the gunwales are clearly those of birds; and the similar situation (though the archer is now a gunman) depicted in a 1594 print by Bertelli (Fig 7) [30].

Hunting grebes, not cormorants?

There is yet another popular interpretation, which requires us to question whether the birds are cormorants at all. Beike argues that although the birds sitting on the boats are cormorants, both the corpses and the birds in the water are in fact great crested grebes (podiceps autitis) [31]. At various times, the plumage of these birds, referred to as “grebe fur” -- prepared belly skins with feathers still attached, stripped from the dead bird -- has been extremely highly valued, being used as a fashion accessary on hats, and for clothes trimmings. Grebe fur was regarded as a luxury item in the eighteenth century, and in the mid-nineteenth century the demand became so frenetic that the grebe population in Britain was almost wiped out.

This theory has support from Howell’s account, cited previously, which states that the type of bird being hunted is a “fisolo” (Fig 8). It seems that these are marsh birds, still widespread in the Venetian Lagoon today, and are actually a type of grebe, not a cormorant [32]. Again, however, there are the seemingly-inevitable objections. If the men are hunting grebes, what are the cormorants doing on the boat? And what is the point of the open-air bird pen on the reed island?

There is yet another popular interpretation, which requires us to question whether the birds are cormorants at all. Beike argues that although the birds sitting on the boats are cormorants, both the corpses and the birds in the water are in fact great crested grebes (podiceps autitis) [31]. At various times, the plumage of these birds, referred to as “grebe fur” -- prepared belly skins with feathers still attached, stripped from the dead bird -- has been extremely highly valued, being used as a fashion accessary on hats, and for clothes trimmings. Grebe fur was regarded as a luxury item in the eighteenth century, and in the mid-nineteenth century the demand became so frenetic that the grebe population in Britain was almost wiped out.

This theory has support from Howell’s account, cited previously, which states that the type of bird being hunted is a “fisolo” (Fig 8). It seems that these are marsh birds, still widespread in the Venetian Lagoon today, and are actually a type of grebe, not a cormorant [32]. Again, however, there are the seemingly-inevitable objections. If the men are hunting grebes, what are the cormorants doing on the boat? And what is the point of the open-air bird pen on the reed island?

These objections aside, the crucial issue on which this theory stands or falls is the correct identification of the birds in the water. This raises the question of the extent to which we can rely on Carpaccio to provide a literal, realistic depiction. He is certainly fond of painting birds, and often they are very closely observed. But, even in this painting, one could not rely on all of his depictions, particularly those of the birds flying in the distance. The one flying off into the sky to the left, for example, has a neck which must be ten feet long, which seems unlikely.

Even assuming Carpaccio has been rigorously accurate, the true position remains somewhat unclear. It must be said that the foreground bird – the one that is depicted as actually being fired at (as distinct from aimed at) -- looks more like a pied cormorant, particularly with its characteristic low ride in the water. Confusingly, the other swimming bird, beyond the diving bird, seems to have a red eye (see the high-res image), which is highly characteristic of grebes, and not of cormorants, yet it has a distinctly curved tip of its bill, a characteristic more common to cormorants than grebes. Which state of confusion leads us to our final theory….

A little bit of everything?

Perhaps one solution to this is that both cormorants and grebes are present, and that Carpaccio is simply depicting hunting in all its guises. Ironically, this rather clunky scenario is actually that first suggested by Busiri-Vici, the person who re-discovered the painting in 1944 [33] – that the men are hunting grebes with terracotta pellets for plumage, that the corpses are dead grebes, and that cormorants have also been brought along to catch fish as an entirely separate activity. If we can ignore the issue of bird identification (particularly in relation to the bird being fired at), this scenario seems to cover most bases, though it seems strange that the men would bother to bring trained cormorants along then devote all their activities to killing grebes, with no evidence at all of any fishing being done. Of course, if the theory is modified so that we interpret the birds sitting on the boats simply as attractive artificial decoys, the force of this particular objection recedes.

Even assuming Carpaccio has been rigorously accurate, the true position remains somewhat unclear. It must be said that the foreground bird – the one that is depicted as actually being fired at (as distinct from aimed at) -- looks more like a pied cormorant, particularly with its characteristic low ride in the water. Confusingly, the other swimming bird, beyond the diving bird, seems to have a red eye (see the high-res image), which is highly characteristic of grebes, and not of cormorants, yet it has a distinctly curved tip of its bill, a characteristic more common to cormorants than grebes. Which state of confusion leads us to our final theory….

A little bit of everything?

Perhaps one solution to this is that both cormorants and grebes are present, and that Carpaccio is simply depicting hunting in all its guises. Ironically, this rather clunky scenario is actually that first suggested by Busiri-Vici, the person who re-discovered the painting in 1944 [33] – that the men are hunting grebes with terracotta pellets for plumage, that the corpses are dead grebes, and that cormorants have also been brought along to catch fish as an entirely separate activity. If we can ignore the issue of bird identification (particularly in relation to the bird being fired at), this scenario seems to cover most bases, though it seems strange that the men would bother to bring trained cormorants along then devote all their activities to killing grebes, with no evidence at all of any fishing being done. Of course, if the theory is modified so that we interpret the birds sitting on the boats simply as attractive artificial decoys, the force of this particular objection recedes.

Part 3: Two Venetian Ladies

Courtesans or patricians?

Let us now turn to the Two Venetian Ladies (Fig 9). This painting depicts two expensively-dressed women seated on what appears to be a rooftop terrace (altana). Both seem to have bored expressions; one, holding a handkerchief, stares rather blankly at something beyond the left frame of the picture, the other older one, closer to us, is also looking off to our left.

Let us now turn to the Two Venetian Ladies (Fig 9). This painting depicts two expensively-dressed women seated on what appears to be a rooftop terrace (altana). Both seem to have bored expressions; one, holding a handkerchief, stares rather blankly at something beyond the left frame of the picture, the other older one, closer to us, is also looking off to our left.

A variety of birds – dove, parrot, peacock – also appear, as well as two dogs [34]. One of those, teeth bared, is pulling rather listlessly at a whisk or cord, with its paw resting on a piece of paper. The other smaller dog, seated on its hindquarters, is having its paws held by the older woman, and looks out with a reserved or even peevish expression at the viewer. A small boy, possibly a page/messenger (some say a dwarf), has somehow clambered through the balustrade and appears to be reaching out to play with the peahen.

Considered in isolation, it is almost impossible to discern what, if anything, is supposed to be happening here. In the absence of the left-hand counterpart panel, we can only guess at what has engaged the women’s rather begrudging attention. So what can we say about the women themselves?

Firstly, it seems to be generally agreed that the painting is not intended to be a portrait of two particular women. Lisa Vitela points out that it does not conform to the formal conventions of Venetian portraiture, and that there is no precedent in Italian painting for a full length individual or double portrait in its own right. Rather, it seems to be an early version of a genre scene of ordinary daily life [35].

Secondly, we know that the women are dressed in the height of Venetian fashion at the time. Their characteristic high-waisted dresses, slashed sleeves, gold threaded materials and adornments of pearls and silver all testify to wealth. We can also say that they represent every aspect of the then-current Italian ideal of beauty -- brown eyes, golden hair, plucked eyebrows, red lips, long slender hands and firm breasts. Their mere presence on the terrace, with an impressive coast of arms decorating the vase on the balustrade, also hints at high birth [36].

However, maybe all is not what it seems. During the 19th century, suggestions were made that the women were not in fact nobility at all – rather they were merely courtesans waiting for their clients. They were actually likened to witches, sorcerers or tramps in an 1852 guidebook, and subsequently described as courtesans in 1906 [37]. These interpretations were based on factors such as the prevalence of a flourishing courtesan culture in Venice, the women’s ostentatious and revealing attire (including their generous décolletage), the "sloth" exhibited by their inactivity, the supposed penchant of courtesans for pets and the iconographic symbolism of objects such as the peacock (symbol of pride) and the supposedly characteristic pair of red clogs [38].

The influential critic, John Ruskin, also hinted at the theme that the painting was a criticism of the vices of society. Ruskin actually played a major role in popularising the painting, even describing it extravagantly as the best picture in the world [39]. Ruskin said, “I know no other which unites every nameable quality of painters art in so intense a degree – breadth with tenderness, brilliancy with quietness, decision with minuteness, colour with light and shade: all that is faithfullest in Holland, fancifullest in Venice, severest in Florence, naturlest in England. Whatever de Hooghe would do in shade, van Eyck in detail, Giorgione in mass, Titian in colour, Bewick and Landseer in animal life, is here at once, and I know no other picture in the world which can be compared with it”[40].

Not everyone was equally impressed. In 1914. EV Lucas wrote that the work was “quaint and ugly but fascinating”, and noted that it was “said to represent two courtesans at home – [though] why it should not equally represent two ladies of unimpeachable character, I cannot see” [41]. His judgment on the courtesan issue has since been generally (but not unanimously) supported, and current interpretations now tend to favour the original view that the women are in fact patricians after all. As evidence for this view, for example, Cohen points out that the hairstyle, mode of attire, passivity and even the way of holding the handkerchief all belong to artistic conventions generally reserved for the upper class. Wills points also to the patrician crest on the vase, and various symbols of chastity and marriage – the lily of virtue, the turtledoves of love, the myrtle of constancy, the dogs representing fidelity and so on [42]. And Vitela adds that Venetian courtesan culture in fact only became famous and increasingly established well after the execution of the painting [43].

A celebration of gender roles? Or a critique?

This revised view of Two Ladies was reinforced by the discovery of Hunting, the upper panel depicting the men’s activities on the lagoon. In this context, the composite painting is now seen by some as a reflection of the gender differences existing in Venice at the time. So, a contrast is drawn between the role of the men in the upper panel – engaged in active, public, outdoor pursuits – and the women in the lower panel. On this view, these women are interpreted as representing passivity, beauty and female chastity in a private enclosed domestic setting, totally appropriate for Venice at that time, where women were rarely let out unattended in public [44].

Of course, even if Carpaccio is depicting these differences in gender roles, this does not necessarily mean that he is criticising them. He may in fact be simply neutral on the issue, or even be promoting their existence. So, for example, it has been suggested that the composite painting may have been commissioned as a wedding gift. On this view, the younger woman is a new bride, the older a protector. The hunting depicted in the upper panel is assumed to be a well-established symbol of courtship and the passionate pursuit of love [45]. Instead of the suggestion that the painting may have been intended to be installed in a study [46], Cohen therefore suggests that it may have been intended for a piece of furniture in a domestic bedroom – as a reminder of the behaviour that was expected of the woman as bride and mother, together with moral warnings about lapses. On this view, a document shown in the trompe l’oeil letter rack on the reverse of the upper panel might represent the notarised documents for the marriage agreement.

Of course, such a subjugated and submissive role does not chime well with more modern social attitudes. Some have suggested that Carpaccio has actually injected a note of criticism or even satire into the painting. This could take two forms. If Two Ladies is interpreted as depicting courtesans, it is possible to argue that it is a satire against the vices of society, particularly the prevalence of prostitutes in Carpaccio’s time. On the other hand, if the painting is interpreted as two patricians, it is possible to argue that Carpaccio is critiquing the inferior status or position of women in Venetian society, not just impassively depicting it, let alone celebrating it. So, for example, Wills has said that the contrast drawn by the painting – the sheltered and idle women waiting at home while the active men are out dominating nature -- is “almost didactically proto-feminist in its sympathy for those left in their gilded cage” [47]. While this is certainly possible – and is supported by the womens’ apparently bored expressions and their total inattention to the macho activity on the lagoon [48] -- it runs the danger of attributing to Carpaccio an attitude that he simply may not have had back in 1495.

So, where have we got to in “understanding” this painting? Of course, so much more would become clearer if the missing left-hand panels somehow magically turned up. In the meantime, it’s up to us to make up our own minds on each of the issues, based on such evidence as is available. Sometimes, however, just having an appreciation of a painting’s complexities and enigmas can be its own reward.

© Philip McCouat 2015, 2019

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Carpaccio’s double enigma: Hunting on the Lagoon and the Two Venetian Ladies”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to Home

End Notes

1. Ian Chilvers, The Oxford Dictionary of Art, entry on Carpaccio.

2. George R Goldner, “A Late Fifteenth Century Venetian Painting of a Bird Hunt”, The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal, Vol. 8 (1980) 22. The separation must presumably have been done sometime before 1780; the reason for it is not clear, though it may possibly have been to multiply profits: Rebecca M Norris, “Carpaccio’s ‘Hunting on the Lagoon’ and ‘Two Venetian Ladies’: A Vignette of Fifteenth-Century Venetian Life”, Thesis, 2007, at 23 http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=kent1185214455

3. Goldner, op cit.

4. Yvonne Szafran, “’Carpacio’s ‘Hunting on the Lagoon’; A New Perspective”, The Burlington Magazine Vol 137, No 1104 (Mar 1995) 148. See also the Getty Museum video at http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/video/134937/reconstruction-of-vittore-carpaccio's-hunting-on-the-lagoon/

5. Elfriede R Knauer, “Fishing with cormorants: a note on Vittore Carpaccio's Hunting on the Lagoon”, Apollo, 158 No 499 September 2003, 32.

6. Goldner, op cit at 27.

7. Goldner, op cit.

7A. The barriers, stakes and other structures indicate this this is a sort of fish farm, typically owned by noble families.

8. See generally Kate Lowe, “Visible Lives: Black Gondoliers and Other Black Africans in Renaissance Venice”, Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 66, No. 2 (Summer 2013), 412.

9. Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, What Great Paintings Say, Vol 1, Taschen, Cologne, 2003 at 107.

10. This view is favoured by the Getty itself: see http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/686/vittore-carpaccio-hunting-on-the-lagoon-recto-letter-rack-verso-italian-venetian-about-1490-1495/

11. Norris, op cit at 41-2; Arthur Graves Credland, “The Pellet Bow in Europe and the East,” Journal of the Society of Archer Antiquaries, Volume 18 (1975): 13 42.

12. Pierre Belon (1517-1564), L’histoire de la natvre des oyseavx, avec levrs descriptions, & naÏfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres, Gilles Corrozet, Paris,1555 at 161; accessed at http://www.e-rara.ch/nev_r/oiseaux/content/titleinfo/1893429

13. James Howell, A survay of the signorie of Venice, of her admired policy, and method of government, &c. with a cohortation to all Christian princes to resent her dangerous condition at present, London 1651 at 188/9; accessed at: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A44752.0001.001/1:10.2?rgn=div2;view=fulltext . Some of the spelling and grammar have been simplified for easier comprehension.

14. Knauer, op cit, though they are reputedly eaten in Norway.

15. Alan Davidson, Oxford Companion to Food, at 390.

16. Belon, op cit at 266.

17. Count de Buffon, Natural History General and Particular Vol IX (History of Birds), 1912 at 307.

18. Marcus Beike, “Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis in Europe – indigenous or introduced?” Ornis Fennica 91: 48, 2014 at 51.

19. Arrigo Cipriani, The Harry’s Bar Cookbook, Blake Publishing, 2000, at 216.

20. Jan Morris, Ciao Carpaccio! Liveright, London and New York, 2014 at 17.

21. I am indebted to Punia Jeffery for this suggestion. Many thanks also go to Louise Egerton, Rob Wall and Robin Hermans for their expertise.

22. In Japan, decoy birds were commonly used to lure cormorants to be used for training http://www.gifu-rc.jp/ukai/u_main.html.

23. Knauer, op cit. The practice possibly goes back to the tenth century in China and the seventh century in Japan. In Japan, the practice is known as "ukai".

24. EW Gudger, “Fishing with the Cormorant: 1: In China”, The American Naturalist Vol. 60, No. 666 (Jan-Feb 1926), pp. 5-41; B. Laufer, The Domestication of the Cormorant in China and Japan (Field Museum of Natural History, Publication 300), Anthropological Series, vol. XVIII, no. 3, Chicago, 1931.

25. In China trained birds were restrained by cords or held in cages: Gudger, op cit.

26. Beike, op cit.

27. Gudger reports that in China any necessary “reminder” to the cormorants took the form of simply splashing the water with an oar, or tapping the birds on the head with a rod: Gudger op cit. Perhaps for the cormorant fishing theory to work we would need to postulate that the pellets are hollow in order for them to have the desired “friendly” effect.

28. And on some of the other boats.

29. In China, this enabled the fishing to go on for hours: Gudger, op cit.

30. As another variant of the cormorant fishing interpretation, it may be that the cormorants are being hunted so that they can later be used to train for fishing. This variant avoids the objection that the bird has no fish in its throat, and explains the penned birds on the reed island and the cormorants sitting on the gunwales. But it requires us to adopt the non-fatal pellet theory and raises the obvious issue -- if the object is only to capture the birds for training, where did the corpses come from?

31. Marcus Beike, “History of Cormorant Fishing in Europe”, Vogelwelt 133: 1-21 (2012).

32. See “Recovering traditional boats in Padua”http://squeropadovano.blogspot.com.au/.

33. Goldner, op cit.

34. The number and variety of birds spread over both panels is remarkable.

35. Lisa Boutin Vitela, “Passive Virtue and Active Valour: Carpaccio’s Two Ladies on an Altana above a Hunt”, Comitatus, 43 (2012) 133-146 at 137. See also Norris at 23.

36. Vitela, op cit at 139.

37. G Ludwig and P Molmenti, Vittore Carpaccio, La vita and le opere, Milano, 1906 282-83, cited in Simona Cohen, “The Enigma of Carpaccio’s Venetian Ladies”, Renaissance Studies Vol 19 No 2 p 150-184 April 2005.

38. Cohen, op cit.

39. John Ruskin, St Mark’s Rest, ch 10.

40. Quoted in E V Lucas, A Wanderer in Venice, 1914 at 137.

41. Lucas, op cit.

42. Barry Wills, Venice: Lion City, The Religion of Empire, Simon and Schuster, 2013 at 158-9.

43. Cohen, op cit; Vitela, op cit at 136. See also C M Schuler, “The Courtesan in Art”, in A R Edsy & Ors, Women’s Studies: Special Issue: Women in the Renaissance: An Interdisciplinary Forum (MLA 1989) at 210; Augusto Gentili, "Painting in Venice: 1490-1515", in Venice; Art and Architecture, Vol 1, Konemann, Cologne 1997 at 270 ff.

44. Vitela, op cit at 137; Norris, op cit at 65. In addition, a subject matter of courtesans might seem unlikely if the work was commissioned by the the patrician Mocenigo.

45. Cohen, op cit.

46. Vitela, op cit at 135.

47. Wills, op cit.

48. Gentili, op cit at 272 suggests that the panorama of activity in the lagoon was not intended to be a view from the balcony, but "an allegorical projection of [the women's] thoughts", which might explain their rather glazed expressions.

© Philip McCouat 2015, 2019

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Carpaccio’s double enigma: Hunting on the Lagoon and the Two Venetian Ladies”, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to Home

Considered in isolation, it is almost impossible to discern what, if anything, is supposed to be happening here. In the absence of the left-hand counterpart panel, we can only guess at what has engaged the women’s rather begrudging attention. So what can we say about the women themselves?

Firstly, it seems to be generally agreed that the painting is not intended to be a portrait of two particular women. Lisa Vitela points out that it does not conform to the formal conventions of Venetian portraiture, and that there is no precedent in Italian painting for a full length individual or double portrait in its own right. Rather, it seems to be an early version of a genre scene of ordinary daily life [35].

Secondly, we know that the women are dressed in the height of Venetian fashion at the time. Their characteristic high-waisted dresses, slashed sleeves, gold threaded materials and adornments of pearls and silver all testify to wealth. We can also say that they represent every aspect of the then-current Italian ideal of beauty -- brown eyes, golden hair, plucked eyebrows, red lips, long slender hands and firm breasts. Their mere presence on the terrace, with an impressive coast of arms decorating the vase on the balustrade, also hints at high birth [36].

However, maybe all is not what it seems. During the 19th century, suggestions were made that the women were not in fact nobility at all – rather they were merely courtesans waiting for their clients. They were actually likened to witches, sorcerers or tramps in an 1852 guidebook, and subsequently described as courtesans in 1906 [37]. These interpretations were based on factors such as the prevalence of a flourishing courtesan culture in Venice, the women’s ostentatious and revealing attire (including their generous décolletage), the "sloth" exhibited by their inactivity, the supposed penchant of courtesans for pets and the iconographic symbolism of objects such as the peacock (symbol of pride) and the supposedly characteristic pair of red clogs [38].

The influential critic, John Ruskin, also hinted at the theme that the painting was a criticism of the vices of society. Ruskin actually played a major role in popularising the painting, even describing it extravagantly as the best picture in the world [39]. Ruskin said, “I know no other which unites every nameable quality of painters art in so intense a degree – breadth with tenderness, brilliancy with quietness, decision with minuteness, colour with light and shade: all that is faithfullest in Holland, fancifullest in Venice, severest in Florence, naturlest in England. Whatever de Hooghe would do in shade, van Eyck in detail, Giorgione in mass, Titian in colour, Bewick and Landseer in animal life, is here at once, and I know no other picture in the world which can be compared with it”[40].

Not everyone was equally impressed. In 1914. EV Lucas wrote that the work was “quaint and ugly but fascinating”, and noted that it was “said to represent two courtesans at home – [though] why it should not equally represent two ladies of unimpeachable character, I cannot see” [41]. His judgment on the courtesan issue has since been generally (but not unanimously) supported, and current interpretations now tend to favour the original view that the women are in fact patricians after all. As evidence for this view, for example, Cohen points out that the hairstyle, mode of attire, passivity and even the way of holding the handkerchief all belong to artistic conventions generally reserved for the upper class. Wills points also to the patrician crest on the vase, and various symbols of chastity and marriage – the lily of virtue, the turtledoves of love, the myrtle of constancy, the dogs representing fidelity and so on [42]. And Vitela adds that Venetian courtesan culture in fact only became famous and increasingly established well after the execution of the painting [43].

A celebration of gender roles? Or a critique?

This revised view of Two Ladies was reinforced by the discovery of Hunting, the upper panel depicting the men’s activities on the lagoon. In this context, the composite painting is now seen by some as a reflection of the gender differences existing in Venice at the time. So, a contrast is drawn between the role of the men in the upper panel – engaged in active, public, outdoor pursuits – and the women in the lower panel. On this view, these women are interpreted as representing passivity, beauty and female chastity in a private enclosed domestic setting, totally appropriate for Venice at that time, where women were rarely let out unattended in public [44].

Of course, even if Carpaccio is depicting these differences in gender roles, this does not necessarily mean that he is criticising them. He may in fact be simply neutral on the issue, or even be promoting their existence. So, for example, it has been suggested that the composite painting may have been commissioned as a wedding gift. On this view, the younger woman is a new bride, the older a protector. The hunting depicted in the upper panel is assumed to be a well-established symbol of courtship and the passionate pursuit of love [45]. Instead of the suggestion that the painting may have been intended to be installed in a study [46], Cohen therefore suggests that it may have been intended for a piece of furniture in a domestic bedroom – as a reminder of the behaviour that was expected of the woman as bride and mother, together with moral warnings about lapses. On this view, a document shown in the trompe l’oeil letter rack on the reverse of the upper panel might represent the notarised documents for the marriage agreement.

Of course, such a subjugated and submissive role does not chime well with more modern social attitudes. Some have suggested that Carpaccio has actually injected a note of criticism or even satire into the painting. This could take two forms. If Two Ladies is interpreted as depicting courtesans, it is possible to argue that it is a satire against the vices of society, particularly the prevalence of prostitutes in Carpaccio’s time. On the other hand, if the painting is interpreted as two patricians, it is possible to argue that Carpaccio is critiquing the inferior status or position of women in Venetian society, not just impassively depicting it, let alone celebrating it. So, for example, Wills has said that the contrast drawn by the painting – the sheltered and idle women waiting at home while the active men are out dominating nature -- is “almost didactically proto-feminist in its sympathy for those left in their gilded cage” [47]. While this is certainly possible – and is supported by the womens’ apparently bored expressions and their total inattention to the macho activity on the lagoon [48] -- it runs the danger of attributing to Carpaccio an attitude that he simply may not have had back in 1495.

So, where have we got to in “understanding” this painting? Of course, so much more would become clearer if the missing left-hand panels somehow magically turned up. In the meantime, it’s up to us to make up our own minds on each of the issues, based on such evidence as is available. Sometimes, however, just having an appreciation of a painting’s complexities and enigmas can be its own reward.

© Philip McCouat 2015, 2019

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Carpaccio’s double enigma: Hunting on the Lagoon and the Two Venetian Ladies”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to Home

End Notes

1. Ian Chilvers, The Oxford Dictionary of Art, entry on Carpaccio.

2. George R Goldner, “A Late Fifteenth Century Venetian Painting of a Bird Hunt”, The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal, Vol. 8 (1980) 22. The separation must presumably have been done sometime before 1780; the reason for it is not clear, though it may possibly have been to multiply profits: Rebecca M Norris, “Carpaccio’s ‘Hunting on the Lagoon’ and ‘Two Venetian Ladies’: A Vignette of Fifteenth-Century Venetian Life”, Thesis, 2007, at 23 http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=kent1185214455

3. Goldner, op cit.

4. Yvonne Szafran, “’Carpacio’s ‘Hunting on the Lagoon’; A New Perspective”, The Burlington Magazine Vol 137, No 1104 (Mar 1995) 148. See also the Getty Museum video at http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/video/134937/reconstruction-of-vittore-carpaccio's-hunting-on-the-lagoon/

5. Elfriede R Knauer, “Fishing with cormorants: a note on Vittore Carpaccio's Hunting on the Lagoon”, Apollo, 158 No 499 September 2003, 32.

6. Goldner, op cit at 27.

7. Goldner, op cit.

7A. The barriers, stakes and other structures indicate this this is a sort of fish farm, typically owned by noble families.

8. See generally Kate Lowe, “Visible Lives: Black Gondoliers and Other Black Africans in Renaissance Venice”, Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 66, No. 2 (Summer 2013), 412.

9. Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, What Great Paintings Say, Vol 1, Taschen, Cologne, 2003 at 107.

10. This view is favoured by the Getty itself: see http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/686/vittore-carpaccio-hunting-on-the-lagoon-recto-letter-rack-verso-italian-venetian-about-1490-1495/

11. Norris, op cit at 41-2; Arthur Graves Credland, “The Pellet Bow in Europe and the East,” Journal of the Society of Archer Antiquaries, Volume 18 (1975): 13 42.

12. Pierre Belon (1517-1564), L’histoire de la natvre des oyseavx, avec levrs descriptions, & naÏfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres, Gilles Corrozet, Paris,1555 at 161; accessed at http://www.e-rara.ch/nev_r/oiseaux/content/titleinfo/1893429

13. James Howell, A survay of the signorie of Venice, of her admired policy, and method of government, &c. with a cohortation to all Christian princes to resent her dangerous condition at present, London 1651 at 188/9; accessed at: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A44752.0001.001/1:10.2?rgn=div2;view=fulltext . Some of the spelling and grammar have been simplified for easier comprehension.

14. Knauer, op cit, though they are reputedly eaten in Norway.

15. Alan Davidson, Oxford Companion to Food, at 390.

16. Belon, op cit at 266.

17. Count de Buffon, Natural History General and Particular Vol IX (History of Birds), 1912 at 307.

18. Marcus Beike, “Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis in Europe – indigenous or introduced?” Ornis Fennica 91: 48, 2014 at 51.

19. Arrigo Cipriani, The Harry’s Bar Cookbook, Blake Publishing, 2000, at 216.

20. Jan Morris, Ciao Carpaccio! Liveright, London and New York, 2014 at 17.

21. I am indebted to Punia Jeffery for this suggestion. Many thanks also go to Louise Egerton, Rob Wall and Robin Hermans for their expertise.

22. In Japan, decoy birds were commonly used to lure cormorants to be used for training http://www.gifu-rc.jp/ukai/u_main.html.

23. Knauer, op cit. The practice possibly goes back to the tenth century in China and the seventh century in Japan. In Japan, the practice is known as "ukai".

24. EW Gudger, “Fishing with the Cormorant: 1: In China”, The American Naturalist Vol. 60, No. 666 (Jan-Feb 1926), pp. 5-41; B. Laufer, The Domestication of the Cormorant in China and Japan (Field Museum of Natural History, Publication 300), Anthropological Series, vol. XVIII, no. 3, Chicago, 1931.

25. In China trained birds were restrained by cords or held in cages: Gudger, op cit.

26. Beike, op cit.

27. Gudger reports that in China any necessary “reminder” to the cormorants took the form of simply splashing the water with an oar, or tapping the birds on the head with a rod: Gudger op cit. Perhaps for the cormorant fishing theory to work we would need to postulate that the pellets are hollow in order for them to have the desired “friendly” effect.

28. And on some of the other boats.

29. In China, this enabled the fishing to go on for hours: Gudger, op cit.

30. As another variant of the cormorant fishing interpretation, it may be that the cormorants are being hunted so that they can later be used to train for fishing. This variant avoids the objection that the bird has no fish in its throat, and explains the penned birds on the reed island and the cormorants sitting on the gunwales. But it requires us to adopt the non-fatal pellet theory and raises the obvious issue -- if the object is only to capture the birds for training, where did the corpses come from?

31. Marcus Beike, “History of Cormorant Fishing in Europe”, Vogelwelt 133: 1-21 (2012).

32. See “Recovering traditional boats in Padua”http://squeropadovano.blogspot.com.au/.

33. Goldner, op cit.

34. The number and variety of birds spread over both panels is remarkable.

35. Lisa Boutin Vitela, “Passive Virtue and Active Valour: Carpaccio’s Two Ladies on an Altana above a Hunt”, Comitatus, 43 (2012) 133-146 at 137. See also Norris at 23.

36. Vitela, op cit at 139.

37. G Ludwig and P Molmenti, Vittore Carpaccio, La vita and le opere, Milano, 1906 282-83, cited in Simona Cohen, “The Enigma of Carpaccio’s Venetian Ladies”, Renaissance Studies Vol 19 No 2 p 150-184 April 2005.

38. Cohen, op cit.

39. John Ruskin, St Mark’s Rest, ch 10.

40. Quoted in E V Lucas, A Wanderer in Venice, 1914 at 137.

41. Lucas, op cit.

42. Barry Wills, Venice: Lion City, The Religion of Empire, Simon and Schuster, 2013 at 158-9.

43. Cohen, op cit; Vitela, op cit at 136. See also C M Schuler, “The Courtesan in Art”, in A R Edsy & Ors, Women’s Studies: Special Issue: Women in the Renaissance: An Interdisciplinary Forum (MLA 1989) at 210; Augusto Gentili, "Painting in Venice: 1490-1515", in Venice; Art and Architecture, Vol 1, Konemann, Cologne 1997 at 270 ff.

44. Vitela, op cit at 137; Norris, op cit at 65. In addition, a subject matter of courtesans might seem unlikely if the work was commissioned by the the patrician Mocenigo.

45. Cohen, op cit.

46. Vitela, op cit at 135.

47. Wills, op cit.

48. Gentili, op cit at 272 suggests that the panorama of activity in the lagoon was not intended to be a view from the balcony, but "an allegorical projection of [the women's] thoughts", which might explain their rather glazed expressions.

© Philip McCouat 2015, 2019

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Carpaccio’s double enigma: Hunting on the Lagoon and the Two Venetian Ladies”, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to Home