The discovery of an early graphic novel

Charles Sarka's long-delayed claim to fame

By Philip McCouat

In February 2010, a remarkable document surfaced in New York. Entitled Song Without Music, the unbound narrative-in-pictures humorously recounts the life of an artist, his hand to mouth existence, and his struggles to succeed [1]. Its existence had not previously been known to the public.

The manuscript emerged at an exhibition held by a New York gallery, Jack the Pelican. The gallery’s director, Don Carroll, said that he had long used the work as a sort of bible for aspiring artists who exhibited at the gallery. With a message of “Jest keep pecking away”, the anonymous work is dedicated to the “the down and outs, the never-was-its and the allso-rans, in the Year of the Profits 1921”.

The timing of its release was dictated by the fact that the gallery was about to go out of business, and Carroll wished to “celebrate” the gallery’s last exhibition by displaying the manuscript in public for the first time [2]. Carroll commented that Song applies to everyone who struggles against the odds and the day-to-day adversities of being an artist: “In the early days of Jack the Pelican, we invited all our artists to read it. It was akin to an initiation”, he said, “We always called it The Sacred Comic Book. It’s not really much of a mission statement for a gallery, but it was the closest thing we had.”

Carroll had another equally-important motive in exhibiting the work – to finally reveal that the anonymous manuscript’s true author was an artist named Charles Nicolas Sarka (1879-1960). Although Sarka had been a well-known American watercolorist and illustrator in the early years of the 20th century, he had become almost forgotten in modern times. The timing of his “coming out” was particularly significant, as the exhibition coincided with the 50th anniversary of his death.

In Song Without Music, we follow the life of the artist – a comically exaggerated version of Sarka himself – and are told how he ran away to Tahiti, struggled to make a living, pondered on the fickleness of fame, and observed the great events of his time.

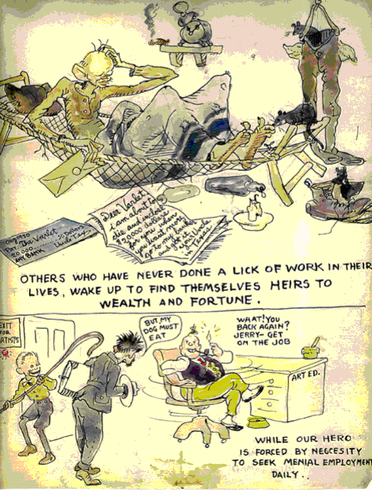

Only a small number of images from Song Without Music have been released, but you can get an idea of its style and contents from the following selection. In Fig 1, Sarka depicts the artist’s struggle to get a commission. In the top panel, a scruffy, undeserving, drunken “varlet” in rat-infested lodgings receives a letter from his “uncle in Texas” with a cheque for $20,000, telling him that if he needs any more he need only go to the uncle’s bank and get it. By contrast, in the lower sketch, Sarka himself – neatly dressed, cap in hand and portfolio under his arm – is about to receive “the hook” towards the “Exit for Artists” from an unsympathetic art editor.

Fig 1: Anon (Charles Sarka), Song Without Music (1921).The letter in the top panel reads, “Dear Varlet, I am about to die and inclose $20,000 dollars for you. When you want more go to my bank and get it – Your Uncle in Texas”. In the bottom panel, the seated Art Editor says, “What! You again? Jerry [the boy with the hook], get on the job. Sarka is protesting, “But my dog must eat”

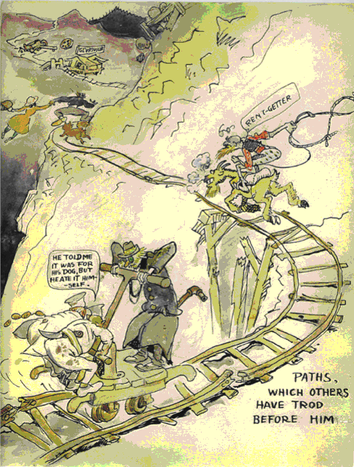

In Fig 2, a penurious Sarka, with wife and dog, appears to be fleeing from a “rent-getter” and two butchers who have evidently not been paid for a purchase of sausages.

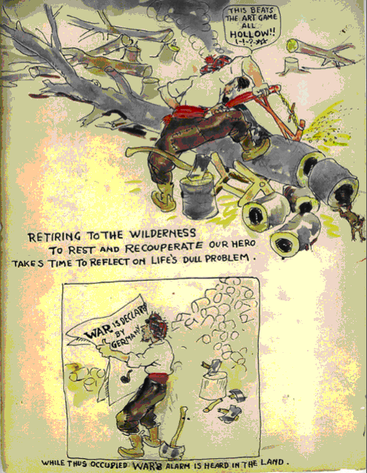

In Fig 3, Sarka has resorted to manual labour, sawing up trees, when World War I is declared.

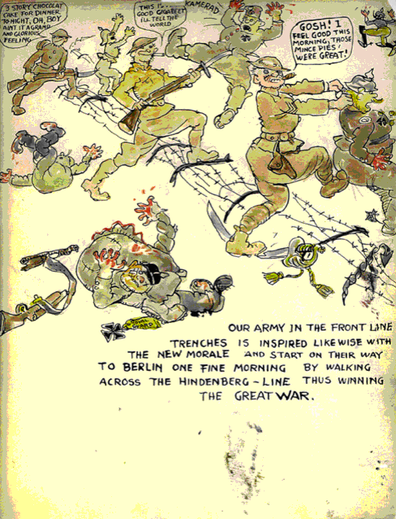

_ The War is eventually won when the troops, supposedly fortified by the “great mince pies” that they’d had that morning, and by the promise of chocolate cake that evening, literally step over the Hindenburg line (Fig 4).

Fig 4: Anon (Charles Sarka), Song Without Music (1921). Trooper top left: “3-story chocolate cake for dinner tonight. Oh boy, ain’t it a grand and glorious feeling”. Middle trooper: “This is a good cigareet. I’ll tell the world”.

Trooper bottom right: “Gosh! I feel good this morning, those mince pies were great!

Carroll describes Song Without Music as “the earliest document of its kind”, and comments on its remarkably contemporary feel: "The first thing that visitors will note is that it looks way too modern to have been drawn in 1921. The pen and brushwork is too fast and furious. Plus, it has a smelly, underground quality that makes it feel very contemporary…. What’s more, it appears to have been influenced by R. Crumb and fired by the imagination of Dr. Seuss – and it’s almost even as curmudgeonly as William Powhida – even though it comes many, many decades before all of them" [3].

In fact, given that it was created in 1921, Song Without Music may have a legitimate claim to be described as one of America’s earliest graphic novels, and possibly the earliest. This raises the question: could it therefore be that Sarka should belatedly be recognised as a father of the American graphic novel?

How serious is this claim? The term “graphic novel” emerged in the 1970s to describe a storytelling format that combines cartoon-style drawings with words and dialogue, but addresses more mature or serious themes than the traditional comic book. Typically, it has a beginning, middle and end, as distinct from being an ongoing series, and normally has an extended length. Unlike “ordinary” comics, it normally does not feature young children (or infantilised adults) and is not primarily directed at them.

On all these counts, Song Without Music appears to qualify as a fully-fledged graphic novel. It has a self-contained story. It features adults and is directed at them. It addresses complex and mature themes – the struggle to survive, the role of art, the nature of fame – and, what’s more, is based (albeit very loosely) on truth..

Sarka’s work is fully 40 pages long. It also appears to be substantially more advanced that other publications that are commonly credited as forerunners of the genre [4]. These include the very early Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck (1842) by Rodolphe Toffler, which looks positively archaic (Fig 5); Richard Outcault’s The Yellow Kid (1895) (Fig 6), which features children; and Hergé’s Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (1929), which is eight years subsequent to Sarka’s work. Other commonly-cited forerunners are distinguished by the fact that they are wordless – for example, Frans Masereel’s Passionate Journey: A Novel in 165 Woodcuts (1926) and Milt Gross’ He Done Her Wrong (1930).

In fact, given that it was created in 1921, Song Without Music may have a legitimate claim to be described as one of America’s earliest graphic novels, and possibly the earliest. This raises the question: could it therefore be that Sarka should belatedly be recognised as a father of the American graphic novel?

How serious is this claim? The term “graphic novel” emerged in the 1970s to describe a storytelling format that combines cartoon-style drawings with words and dialogue, but addresses more mature or serious themes than the traditional comic book. Typically, it has a beginning, middle and end, as distinct from being an ongoing series, and normally has an extended length. Unlike “ordinary” comics, it normally does not feature young children (or infantilised adults) and is not primarily directed at them.

On all these counts, Song Without Music appears to qualify as a fully-fledged graphic novel. It has a self-contained story. It features adults and is directed at them. It addresses complex and mature themes – the struggle to survive, the role of art, the nature of fame – and, what’s more, is based (albeit very loosely) on truth..

Sarka’s work is fully 40 pages long. It also appears to be substantially more advanced that other publications that are commonly credited as forerunners of the genre [4]. These include the very early Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck (1842) by Rodolphe Toffler, which looks positively archaic (Fig 5); Richard Outcault’s The Yellow Kid (1895) (Fig 6), which features children; and Hergé’s Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (1929), which is eight years subsequent to Sarka’s work. Other commonly-cited forerunners are distinguished by the fact that they are wordless – for example, Frans Masereel’s Passionate Journey: A Novel in 165 Woodcuts (1926) and Milt Gross’ He Done Her Wrong (1930).

_ If this is right – and obviously more research may be called for – Sarka may actually have a genuine claim to fame. This would indeed be poignant. Sarka himself once fancifully recounted in his journal how in 1910 he went to an art gallery that “guaranteed fame”. Inside, he found a note from “Art and Fame”, whom he’d been chasing vainly for years. “Sit down and make yourself at home,” it said, “Will be back in 100 years”[5]. Given that the manuscript has now been released exactly that number of years later, maybe Sarka was right all along. □

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013

We welcome your comments on this article

Note: For a fuller account of Charles Sarka’s colourful life and work, including the adventurous travels that earned him the monicker “ Sarka of the South Seas”, see here

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013

We welcome your comments on this article

Note: For a fuller account of Charles Sarka’s colourful life and work, including the adventurous travels that earned him the monicker “ Sarka of the South Seas”, see here

End Notes

1. Details of this work appeared only on the archived website of the exhibiting gallery, Jack the Pelican, of Williamsburg in New York. The work is apparently owned by the ex-gallery’s director. Don Carroll. All images of the work were taken from the website in March 2010.:

2. The exhibition was, rather ominously, advertised as running from “20 February until the marshal comes and shuts the door”. The exhibition apparently lasted a few weeks, when the gallery closed. In an interview, Carroll explained that the gallery had lost its momentum and it had become too expensive to operate. Quoted in The Brooklyn Rail: Critical Perspectives on Arts, Politics and Culture, May 2010 http://www.brooklynrail.org/2010/05/artseen/brooklyn-dispatches-dog-years

3. Jack the Pelican archived website, op cit.

4. Tychinsky, S, A Brief History of the Graphic Novel

5. Jack the Pelican archived website, op cit.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013.

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The discovery of an early graphic novel", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home

2. The exhibition was, rather ominously, advertised as running from “20 February until the marshal comes and shuts the door”. The exhibition apparently lasted a few weeks, when the gallery closed. In an interview, Carroll explained that the gallery had lost its momentum and it had become too expensive to operate. Quoted in The Brooklyn Rail: Critical Perspectives on Arts, Politics and Culture, May 2010 http://www.brooklynrail.org/2010/05/artseen/brooklyn-dispatches-dog-years

3. Jack the Pelican archived website, op cit.

4. Tychinsky, S, A Brief History of the Graphic Novel

5. Jack the Pelican archived website, op cit.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013.

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The discovery of an early graphic novel", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home