Early influences of photography - Part 4

|

By Philip McCouat Pt 1: Initial impacts Pt 2: Photography as a working aid Pt 3: Photographic effects Pt 4: New approaches to “reality” |

More on photography

For other articles on photography, see: Art in a speeded-up world Why wasn’t photography invented earlier? ---------------------------------------------- |

New approaches to "reality"

As we have seen in Part 3, one of the main perceived advantages of photography was that it appeared to give painters a fresh and objective version of reality. Surprisingly to many, however, this version did not always coincide with normal human perceptions of the world. There were a number of reasons for this. The potential focus of a photograph is much wider than a human’s field of vision – much of what humans see is actually quite blurred. Additionally, unlike the unblinking eye of a camera, a human’s perception is dramatically filtered by our level of attention, our emotions and our area of interest [146]. Photography’s speed also reveals a new world of frozen intermediate steps not accessible to normal human perception. This contributes to the impression that time has stopped. It is argued that this also causes the viewer to unconsciously try to stop their personal or biological time. As a result, photographic forms acquire a quality that we rarely experience when looking at painted forms – immediacy [147].

Seeing the body

One of the effects of this was on portraits of nudes. Pornographic photographs had started to be produced in large numbers in 1840s, and were refined by stereoscopy in the 1850s. This development revolutionised pornography in a number of ways. Previously, pornographic paintings typically had quite a limited circulation. Photographs, capable of being carried in a wallet and being handed on under one’s coat, were much more portable and could be circulated in a way that a painting or sculpture could not. Seemingly overnight, they were being sold to a wide (male) market in their thousands in plain packets “under the counter”[148].

This increased portability, with the corollary that they could be touched or held in one’s hand, blurred the line between sight and touch, enhancing the possessor’s tactile experience [149]. Furthermore, photographs provided seemingly irrefutable evidence that there was a real, not imagined, person who was willingly posing, often with apparent enjoyment, for the viewer’s private, long-term pleasure. “Framing” and “taking” a photograph became a new, almost literal, way of “capturing” the subject’s body [150]. The experience thus allowed a far more direct and intimate contact between viewer and subject, a contact that was not mediated through a painter’s imagination, eyes or brush. This realism was further heightened by stereoscopic depth and, in certain cases, by the illusion of movement that could be produced, for example by multiple photos of progressive disrobing.

The heady dangers posed to society by this combination of mass circulation and heightened realism were reflected in the substantial criminal penalties that were imposed in France for possession of pornographic photographs. Much painted pornography suddenly started to look rather old hat [151], though some painters manfully rose to the challenge. Courbet’s infamous Origine du Monde (1866), with its striking similarities to pornographic stereoscopes by Auguste Belloc, set a new painterly standard that can still surprise unsuspecting viewers today with its single-minded anatomical frankness.

Photographic influences also permeated into more mainstream works involving the body. Courbet’s use of photographic nudes as models for paintings such as The Bathers (1853) resulted in a more realistic treatment. While retaining outwardly classical poses, the subject of these paintings revealed more physically “real” women with dirty feet, sagging flesh or bruises from their corset stays. It may even be that Courbet’s works were even more realistic and uncompromising than their photographic precedents [152].

It has also been suggested that Manet’s nudes in Olympia and Luncheon on the Grass have striking similarities to photographic stereoscopes of the 1860s [153], with their candid stares, similar poses, contemporary and rather awkward gestures, unidealised proportions and absence of half tones or interior modelling. Needham suggests that the shocked reaction which greeted these paintings arose precisely because they reminded viewers of prostitutes whose favours they had enjoyed or of whom they had seen photographs.

While Manet evidently used the photographs to heighten the grittiness of his paintings, Delacroix seemingly found it difficult to deal fully with the new reality [154]. As we have seen earlier (Figs 6 and 7), Delacroix seemed to be unable (or unwilling) to break entirely from his pre-existing perceptual framework of the body in his paintings, even though he was intellectually aware of the deviations from reality that this involved. He may have sympathised with Monet, who expressed the wish he had been born blind and then acquired sight so he could paint without knowing what he saw [155].

This increased portability, with the corollary that they could be touched or held in one’s hand, blurred the line between sight and touch, enhancing the possessor’s tactile experience [149]. Furthermore, photographs provided seemingly irrefutable evidence that there was a real, not imagined, person who was willingly posing, often with apparent enjoyment, for the viewer’s private, long-term pleasure. “Framing” and “taking” a photograph became a new, almost literal, way of “capturing” the subject’s body [150]. The experience thus allowed a far more direct and intimate contact between viewer and subject, a contact that was not mediated through a painter’s imagination, eyes or brush. This realism was further heightened by stereoscopic depth and, in certain cases, by the illusion of movement that could be produced, for example by multiple photos of progressive disrobing.

The heady dangers posed to society by this combination of mass circulation and heightened realism were reflected in the substantial criminal penalties that were imposed in France for possession of pornographic photographs. Much painted pornography suddenly started to look rather old hat [151], though some painters manfully rose to the challenge. Courbet’s infamous Origine du Monde (1866), with its striking similarities to pornographic stereoscopes by Auguste Belloc, set a new painterly standard that can still surprise unsuspecting viewers today with its single-minded anatomical frankness.

Photographic influences also permeated into more mainstream works involving the body. Courbet’s use of photographic nudes as models for paintings such as The Bathers (1853) resulted in a more realistic treatment. While retaining outwardly classical poses, the subject of these paintings revealed more physically “real” women with dirty feet, sagging flesh or bruises from their corset stays. It may even be that Courbet’s works were even more realistic and uncompromising than their photographic precedents [152].

It has also been suggested that Manet’s nudes in Olympia and Luncheon on the Grass have striking similarities to photographic stereoscopes of the 1860s [153], with their candid stares, similar poses, contemporary and rather awkward gestures, unidealised proportions and absence of half tones or interior modelling. Needham suggests that the shocked reaction which greeted these paintings arose precisely because they reminded viewers of prostitutes whose favours they had enjoyed or of whom they had seen photographs.

While Manet evidently used the photographs to heighten the grittiness of his paintings, Delacroix seemingly found it difficult to deal fully with the new reality [154]. As we have seen earlier (Figs 6 and 7), Delacroix seemed to be unable (or unwilling) to break entirely from his pre-existing perceptual framework of the body in his paintings, even though he was intellectually aware of the deviations from reality that this involved. He may have sympathised with Monet, who expressed the wish he had been born blind and then acquired sight so he could paint without knowing what he saw [155].

Capturing sequential movement

Photography’s capacity to capture impressions faster than the human eye gave artists unprecedentedly accurate information as to how things moved. In 1878, Muybridge’s sensational exhibition of short-exposure photography disclosed the movement of animals and humans in step-by-step detail. Equally startling “chronophotographic” studies were later produced by Marey, showing successive phases of continuous movement in a single picture (see Changing concepts of time Fig 1). Short-exposure photography of this type expanded the reach of human eyesight in the temporal domain – suddenly the prosaic action of a raindrop falling into a puddle could be transformed into an extraordinary vision.

It seems likely that Muybridge’s work inspired Degas’ renewed interest in depicting racehorses – particularly in intermediate positions not normally perceived by the human eye [156]. It also influenced the portrayal of horses in Eakins’ The Fairman Rogers Four in Hand(1879)[157] and the diving boy in the oddly-frozen Swimmers(1885)[158]. It also prompted. Meissonnier and Remington to correct their former “rocking horse” style depictions of galloping horses. Suddenly there was an outbreak of battle pictures, showing horses charging in every direction, with all four legs off the ground – not since 1815 had the Battle of Waterloo been so popular [159].

It seems likely that Muybridge’s work inspired Degas’ renewed interest in depicting racehorses – particularly in intermediate positions not normally perceived by the human eye [156]. It also influenced the portrayal of horses in Eakins’ The Fairman Rogers Four in Hand(1879)[157] and the diving boy in the oddly-frozen Swimmers(1885)[158]. It also prompted. Meissonnier and Remington to correct their former “rocking horse” style depictions of galloping horses. Suddenly there was an outbreak of battle pictures, showing horses charging in every direction, with all four legs off the ground – not since 1815 had the Battle of Waterloo been so popular [159].

Scharf claims that Degas also made similar corrections [160] but, to my eye, the pre-Muybridge style depicted in Carriage at the Races (1870) is repeated post-Muybridge with the horse in the left background in Racehorses (1888). Seurat, too, is still using the old style – extremely effectively – in Le Cirque (1891), as is Toulouse-Lautrec in The Jockey (1899) and Rousseau in War (1894). Scharf also argues, less convincingly, that it is “more than fortuitous” that Degas’ Scène de Ballet (1879), which shows dancers with legs completely off the ground, appeared at exactly the time Muybridge’s photos were being published in Paris [161].

It is also possible that the sequential, frame-by-frame horizontal presentation of Muybridge’s work may have provided a stimulus for Degas’ unusual Frieze of Dancers, which shows a series of different perspectives of a ballerina tying up her shoes. However, it is equally possible that the work simply reflects a series of studies. In a similar context, it has been suggested that the new photography was reflected in the row of dancers in Seurat’s Le Chahut. However, although Seurat certainly believed that movement could be studied through photography [162], the attribution is not clear-cut. Firstly, the subject of that painting is not successive movements of a single dancer (as in chronophotography), but simultaneous movements of a number of dancers. Secondly,representations of moving, multiple subjects had been frequently appearing in popular journals for some time, and these images had become a familiar part of cartoons ever since the discovery of photography. There are more convincing examples of the influence of chronophotography but, as we shall see, these did not appear until the 20th century – see The "new" time in painting [163].

Of course, the issue is not really about how horses gallop or ballerinas leap – rather it is about the role of objective reality. Changes in one’s perception of objective reality will matter greatly for a painter of realist battle scenes, but may be irrelevant for an artist such as Rousseau whose world is more imaginary. Thus, the “wrong” depictions by Rousseau or Seurat are quite deliberate, and seem to be an essential part of the composition. For example, it is likely that a depiction of a mechanically-correct galloping horse bestriding the scene of human devastation in War would look ridiculous in this scenario.

It is also possible that the sequential, frame-by-frame horizontal presentation of Muybridge’s work may have provided a stimulus for Degas’ unusual Frieze of Dancers, which shows a series of different perspectives of a ballerina tying up her shoes. However, it is equally possible that the work simply reflects a series of studies. In a similar context, it has been suggested that the new photography was reflected in the row of dancers in Seurat’s Le Chahut. However, although Seurat certainly believed that movement could be studied through photography [162], the attribution is not clear-cut. Firstly, the subject of that painting is not successive movements of a single dancer (as in chronophotography), but simultaneous movements of a number of dancers. Secondly,representations of moving, multiple subjects had been frequently appearing in popular journals for some time, and these images had become a familiar part of cartoons ever since the discovery of photography. There are more convincing examples of the influence of chronophotography but, as we shall see, these did not appear until the 20th century – see The "new" time in painting [163].

Of course, the issue is not really about how horses gallop or ballerinas leap – rather it is about the role of objective reality. Changes in one’s perception of objective reality will matter greatly for a painter of realist battle scenes, but may be irrelevant for an artist such as Rousseau whose world is more imaginary. Thus, the “wrong” depictions by Rousseau or Seurat are quite deliberate, and seem to be an essential part of the composition. For example, it is likely that a depiction of a mechanically-correct galloping horse bestriding the scene of human devastation in War would look ridiculous in this scenario.

Seeing the effect of change

The speed of photography also made it obvious that, even for relatively static subjects, reality had a transitory and ever-changing nature. As Szarowski points out “each subtle variation in viewpoint or light, each passing moment, each change in the tonality of the print, caused a new picture…. the wall of a building in the sun was never twice the same” [164]. So perhaps it is no surprise that, at about this time, Monet started painting subjects in multiple series, with multiple canvases under way of the same subject, such as his famous haystacks. Apart from this possible theoretical inspiration, Monet also actually used photographs as a working aid in his extraordinary series of paintings of the light effects on Rouen Cathedral [165]. These represented an attempt to incorporate the dimension of time in the paintings. Spate recounts how Monet would venture out with a group of children, each carrying canvases representing the same subject at different times of the day. Monet then worked on the canvases and put them aside by turn, according to changes in the sky and shadows [166].

Moves beyond photographic reality

In these various ways, photography offered artists new, exploitable insights into a new version of reality. But in some respects, this was a poisoned chalice. Firstly, if photographic reality became the ultimate aim, painting would find it hard to compete, and could be condemned to become photography’s derivative poor cousin -- as James McNeill Whistler pointed out, "[I]f the man who paints only the tree, or flower, or other surface that he sees before him were an artist, the king of artists would be a photographer" [166A]. Secondly, many aspects of photographic reality were not necessarily desirable for many artists. So, for example, the non-selectivity of a photograph may be objective but, as Delacroix noted in his Journal, it also meant that the edge of the scene became as important as the principal subject, interfering with the artistic view [167].

Similarly, as the London Globe pointed out, “art for the purpose of representation does not require to give the eye more than the eye can see, and when [an artist] gives us a picture of a close finish for the Gold Cup, we do not want Mr Muybridge to tell us that no horses ever strode in the fashion shown in the picture. It may indeed be fairly contended that the incorrect position according to science is the correct position according to art”[168].

Paradoxically, too, a photograph may sometimes not reveal enough information on which to base an artistic reality. In 1857, Lady Elizabeth Eastlake argued that mere photography lacked the "artistic feeling" that was necessary to selectively emphasise what was significant. Similarly, John Ruskin, in significantly revising his initial enthusiasm for photography, considered that photography missed certain of the subtleties of natural effect [169A]. In more modern times, David Hockney has commented that for this reason it was impossible to draw solely from photographs. Similarly, the British artist Rowland Hilder noted that he may need to take twenty photos for one painting, and that artists have to learn their job first, “so they know what they are looking for” [169].

It seems likely that these discrepancies contributed to what Clark described as a “kind of scepticism, or at least unsuredness, as to the nature of representation in art”[170]. As we shall see, painters approached this fundamental issue in radically different ways.

In America, some landscapists, such as those in the Hudson River School, took an optimistic, positive approach by attempting to embrace and outdo the version of reality that photography presented, by producing a type of heroic super-landscape, marketed as theatre. For example, with the aid of the detail provided by a massive library of photographic studies, Frederick Church produced paintings such as the enormous Heart of the Andes (Fig 14), which was reputed to telescope one thousand miles of scenery into a single canvas [171]. Spectators were actually encouraged to use binoculars to appreciate the detail of this and other hyper-real paintings of the era. Often these were composites – the one scene could feature multiple waterfalls or mountains drawn from two or more quite different locations.

Similarly, as the London Globe pointed out, “art for the purpose of representation does not require to give the eye more than the eye can see, and when [an artist] gives us a picture of a close finish for the Gold Cup, we do not want Mr Muybridge to tell us that no horses ever strode in the fashion shown in the picture. It may indeed be fairly contended that the incorrect position according to science is the correct position according to art”[168].

Paradoxically, too, a photograph may sometimes not reveal enough information on which to base an artistic reality. In 1857, Lady Elizabeth Eastlake argued that mere photography lacked the "artistic feeling" that was necessary to selectively emphasise what was significant. Similarly, John Ruskin, in significantly revising his initial enthusiasm for photography, considered that photography missed certain of the subtleties of natural effect [169A]. In more modern times, David Hockney has commented that for this reason it was impossible to draw solely from photographs. Similarly, the British artist Rowland Hilder noted that he may need to take twenty photos for one painting, and that artists have to learn their job first, “so they know what they are looking for” [169].

It seems likely that these discrepancies contributed to what Clark described as a “kind of scepticism, or at least unsuredness, as to the nature of representation in art”[170]. As we shall see, painters approached this fundamental issue in radically different ways.

In America, some landscapists, such as those in the Hudson River School, took an optimistic, positive approach by attempting to embrace and outdo the version of reality that photography presented, by producing a type of heroic super-landscape, marketed as theatre. For example, with the aid of the detail provided by a massive library of photographic studies, Frederick Church produced paintings such as the enormous Heart of the Andes (Fig 14), which was reputed to telescope one thousand miles of scenery into a single canvas [171]. Spectators were actually encouraged to use binoculars to appreciate the detail of this and other hyper-real paintings of the era. Often these were composites – the one scene could feature multiple waterfalls or mountains drawn from two or more quite different locations.

_ In Britain, a variety of techniques used by the pre-Raphaelite painters also had the effect of embracing and even outdoing photography’s accuracy. Firstly, there was an emphasis on “truth to nature”, typically by focusing inwards on detail rather than outwards on the wide vista, as the American landscapists had done [172]. This typically involved the use of vivid, high focus, highly-lit colour over the whole of the picture space, providing a stark contrast with monotone photography. It also involved the provision of detail in otherwise hidden areas such as deep shade into which photography could not reach, or the choice of intricate and densely patterned things – ivy covered walls, a pebbled beach – again exploiting areas in which photography was technically deficient. A second differentiator was the use of historical, genre, medieval subjects which photography could not emulate. The result in some cases, such as Millais’ Ophelia (Fig 15) or Ford Madox Brown’s An English Autumn Afternoon (1853), was an exquisite but rather artificial type of super-realism [173]. As with the American landscapists, these approaches would ultimately prove to be relatively short-lived.

In contrast, many other artists were moving in directions that were moving away from reality. The Impressionists, for example, instead of trying merely to replicate how the external world really was, concentrated on how humans perceived it.to be -- paradoxically creating images that initially jarred with many viewers' preconceptions. It is often said that such artists actually felt that photography “liberated” them from the confines of naturalistic representation, enabling them to explore other more expressive, non-naturalistic alternatives in their painting. As Picasso argued in 1906, “Why should an artist persist in treating subjects that can be established so clearly with the lens of a camera? It would be absurd, wouldn’t it? Photography has arrived at a point where it is capable of liberating painting from all literature, from the anecdote and even from the subject … Why shouldn’t painters profit from their newly acquired liberty and make use of it to do other things?” [174].

While there may be some truth in this concept of artists joyously throwing off their long-detested shackles, the true situation was probably much more complex [175]. Obviously, not all artists would react in the same way, or at all – it is significant, for example, that Picasso was talking in 1906 about what he felt should happen, not what had actually occurred [176]. So, while some artists may indeed have felt themselves “freed”, others may equally have felt that this was a less-than-glorious matter of necessity rather than choice [177]. Thus, Eggum, speaking of Norwegian artists in the 1880s, cites the view that “the competition with photography to show realism in its truest form ended up with artists, at any rate the most important of them, withdrawing into tunnels where photography could not reach them, leaving the battlefield to the competitor”[178].

Yet other artists may have seen photography’s role neither as liberating nor a matter of compulsion, but as lying somewhere on the scale from “educative” to “inspiring”. Vaizey, for example, concludes that the camera’s ability to portray the external world “must unconsciously, obliquely and even directly have helped and encouraged artists to look for other kinds of imagery” [179]. The critic Figuier argued that the influence would actually be inspirational, in the sense that comparisons between beautiful photographs and works of painting would force great artists to surpass themselves.

Along these lines, Matisse considered that photography’s “real service was in showing that the artist was concerned with something other than external experience”, and was encouraged to dig down further than he ever had towards the inner source of life and energy – toward the unconscious [180]. Similarly Munch, who considered that “photographic realism leaves one cold”, eventually developed the view that “we want more than just a photograph of nature … We want an art that grasps ... Art created by life blood” (Fig 16)[181]. This, he believed, would ensure that “the camera cannot compete with the brush and palette – as long as it cannot be used in heaven and hell”. André Derain, in talking about the strange colours and flat tones of his Fauvist phase, explained, "It was the era of photography. This may have influenced us and played a part in our reaction against anything resembling a snapshot of life"[181A].

While there may be some truth in this concept of artists joyously throwing off their long-detested shackles, the true situation was probably much more complex [175]. Obviously, not all artists would react in the same way, or at all – it is significant, for example, that Picasso was talking in 1906 about what he felt should happen, not what had actually occurred [176]. So, while some artists may indeed have felt themselves “freed”, others may equally have felt that this was a less-than-glorious matter of necessity rather than choice [177]. Thus, Eggum, speaking of Norwegian artists in the 1880s, cites the view that “the competition with photography to show realism in its truest form ended up with artists, at any rate the most important of them, withdrawing into tunnels where photography could not reach them, leaving the battlefield to the competitor”[178].

Yet other artists may have seen photography’s role neither as liberating nor a matter of compulsion, but as lying somewhere on the scale from “educative” to “inspiring”. Vaizey, for example, concludes that the camera’s ability to portray the external world “must unconsciously, obliquely and even directly have helped and encouraged artists to look for other kinds of imagery” [179]. The critic Figuier argued that the influence would actually be inspirational, in the sense that comparisons between beautiful photographs and works of painting would force great artists to surpass themselves.

Along these lines, Matisse considered that photography’s “real service was in showing that the artist was concerned with something other than external experience”, and was encouraged to dig down further than he ever had towards the inner source of life and energy – toward the unconscious [180]. Similarly Munch, who considered that “photographic realism leaves one cold”, eventually developed the view that “we want more than just a photograph of nature … We want an art that grasps ... Art created by life blood” (Fig 16)[181]. This, he believed, would ensure that “the camera cannot compete with the brush and palette – as long as it cannot be used in heaven and hell”. André Derain, in talking about the strange colours and flat tones of his Fauvist phase, explained, "It was the era of photography. This may have influenced us and played a part in our reaction against anything resembling a snapshot of life"[181A].

Of course, the fact that some artists may have been influenced, directly or indirectly, does not mean that all artists were. One must be wary of any approach that sees artistic innovation simply as a uniform response to outside technological or social influences. Some artists may have been influenced more by trends towards abstraction that had already existed in painting at least since Turner, well before photography had been invented [182]. Others may simply not have been significantly influenced by photographic realism at all, relying on their own instincts, creativity and inclinations to inspire their artistic direction.

As a minimum, however, it does seem that photography’s realism would have encouraged many artists to more closely examine what they individually were trying to achieve in their own art. Man Ray, who spanned both disciplines, summed this up by saying that with photography artists were at last able to know “everything that painting isn’t” [183]. His own resolution was that he would “photograph what I do not wish to paint, and I paint what I cannot photograph”[184].

Definite signs of the emergence of a new type of reality came with Manet, though the role of photography in this is not clear cut. Manet considered that a painting should be recognised as simply the result of the artist’s physical arrangement of paint on a flat surface [185].In some ways, on this view, the form of representation becomes its own subject matter. Similarly, Matisse considered that “the subject of a picture and the background have the same value … there is no principal feature, only the pattern is important”[186]. To this extent, Manet can be characterised as asserting his independence from the external objective reality captured by photography. On the other hand, photography evidently interested Manet, as we have already seen in relation to his probable use of photographs as sources in paintings such as Olympia. Thus, his characteristic painterly flatness can be variously characterised a reaction against photography’s realism or, paradoxically, a reflection of photographic studio backdrops, the normal monocular focus of a photograph [187], the actual physical flatness of photographic prints, or even the flattening effects of photographic flashes [188]. Perhaps the resolution of these ambiguities is that Manet rejected objective reality as his model but embraced and exploited some of the photographic “distortions” of it [189].

Some other painters took a rather different approach, as evidenced by directions taken in portrait painting. This form of painting was especially vulnerable for two reasons. First, it was an area in which realism and recognisability were traditionally regarded as particularly important [190]. Second, portrait painting was an area in which the high level of commissioned portraits, often flattering and commercial, had already compromised standards. Renoir actually welcomed the advent of photography in this area, as he considered that it freed painting from “tiresome chores” such as family portraits. “Now the good shopkeeper [wanting a portrait] only has to go round to the photographer round the corner”, he said, “So much the worse for us, but so much the better for the art of painting” [191].

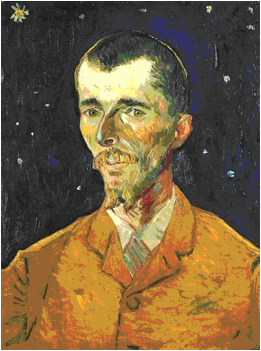

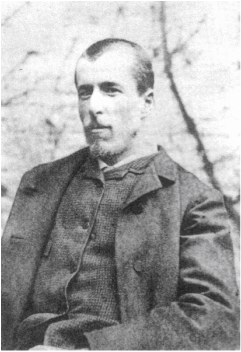

As it happened, portrait painting began moving in a number of directions that photography could not readily follow. Van Gogh provides a particularly clear example, as his motives and approach are explicitly spelled out in his letters. These demonstrate that he was “exasperated by certain people’s photographic and inane perfection”[192], and realised that that there was little point in endeavouring to achieve what he wanted by a “photographic resemblance”. He saw his task as expressing and intensifying the character of his sitters. He therefore consciously differentiated his portraits from photographic reality by a variety of methods. These included exposing, rather than hiding, technique; exploiting colour; adding a psychological dimension; moving toward more abstraction; introducing exaggeration or caricature; and emphasising atmosphere, setting or decoration [193].

Many of these aspects are illustrated by comparing his Portrait of Eugene Boch (1888), the poet, with a similarly-posed photograph of the same subject (Figs 17a and 17b).

As a minimum, however, it does seem that photography’s realism would have encouraged many artists to more closely examine what they individually were trying to achieve in their own art. Man Ray, who spanned both disciplines, summed this up by saying that with photography artists were at last able to know “everything that painting isn’t” [183]. His own resolution was that he would “photograph what I do not wish to paint, and I paint what I cannot photograph”[184].

Definite signs of the emergence of a new type of reality came with Manet, though the role of photography in this is not clear cut. Manet considered that a painting should be recognised as simply the result of the artist’s physical arrangement of paint on a flat surface [185].In some ways, on this view, the form of representation becomes its own subject matter. Similarly, Matisse considered that “the subject of a picture and the background have the same value … there is no principal feature, only the pattern is important”[186]. To this extent, Manet can be characterised as asserting his independence from the external objective reality captured by photography. On the other hand, photography evidently interested Manet, as we have already seen in relation to his probable use of photographs as sources in paintings such as Olympia. Thus, his characteristic painterly flatness can be variously characterised a reaction against photography’s realism or, paradoxically, a reflection of photographic studio backdrops, the normal monocular focus of a photograph [187], the actual physical flatness of photographic prints, or even the flattening effects of photographic flashes [188]. Perhaps the resolution of these ambiguities is that Manet rejected objective reality as his model but embraced and exploited some of the photographic “distortions” of it [189].

Some other painters took a rather different approach, as evidenced by directions taken in portrait painting. This form of painting was especially vulnerable for two reasons. First, it was an area in which realism and recognisability were traditionally regarded as particularly important [190]. Second, portrait painting was an area in which the high level of commissioned portraits, often flattering and commercial, had already compromised standards. Renoir actually welcomed the advent of photography in this area, as he considered that it freed painting from “tiresome chores” such as family portraits. “Now the good shopkeeper [wanting a portrait] only has to go round to the photographer round the corner”, he said, “So much the worse for us, but so much the better for the art of painting” [191].

As it happened, portrait painting began moving in a number of directions that photography could not readily follow. Van Gogh provides a particularly clear example, as his motives and approach are explicitly spelled out in his letters. These demonstrate that he was “exasperated by certain people’s photographic and inane perfection”[192], and realised that that there was little point in endeavouring to achieve what he wanted by a “photographic resemblance”. He saw his task as expressing and intensifying the character of his sitters. He therefore consciously differentiated his portraits from photographic reality by a variety of methods. These included exposing, rather than hiding, technique; exploiting colour; adding a psychological dimension; moving toward more abstraction; introducing exaggeration or caricature; and emphasising atmosphere, setting or decoration [193].

Many of these aspects are illustrated by comparing his Portrait of Eugene Boch (1888), the poet, with a similarly-posed photograph of the same subject (Figs 17a and 17b).

_ Instead of a smooth photographic surface, van Gogh used vigorous brushwork and thickly-applied paint to create a heavily tactile, textured surface. Instead of the limited range of black and white photographs, van Gogh presented a striking and unusual range of exaggerated colours, especially in the flesh tones, which he believed were particularly expressive of character. Instead of the “objectivity” of a photo portrait, the painting exhibits an oddly watchful and slightly unsettled psychological element, accentuated by the agitated brushwork. Together with the exaggeration of the sitter’s thin nose and the starry background [193A], these elements combine to create a striking work that is emphatically non-photographic [194].

Conclusion

Photography was initially demonised by some as a sacrilegious or diabolical invention that would mean the “end of art”. While those predictions proved rather hasty, it is true that photography drove some artists out of work and some minor genres virtually out of existence. Yet it also provided assistance to many painters in their methods of work, expanded their visual resources and possibly their imaginations. Photographic characteristics also probably influenced various elements of composition and style for some painters.

Photography’s ostensible advantage – of presenting an objective version of reality – was met in various ways by those who felt the need. Some painters succumbed, some tried to outdo photography by hyper-realism or detail, while for others the advent of photography helped to crystallise a need to reconsider the nature of painting’s relationship to reality.

Note: As noted at the outset, this article is confined broadly to Western painting in the period from the announcement of the invention in 1839 up until round the end of the nineteenth century. It is a companion to The ‘New’ Time in Painting, which examines the impact that changing concepts of time had on painting, particularly in the 20th century.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2018

We welcome your comments on this article

Photography’s ostensible advantage – of presenting an objective version of reality – was met in various ways by those who felt the need. Some painters succumbed, some tried to outdo photography by hyper-realism or detail, while for others the advent of photography helped to crystallise a need to reconsider the nature of painting’s relationship to reality.

Note: As noted at the outset, this article is confined broadly to Western painting in the period from the announcement of the invention in 1839 up until round the end of the nineteenth century. It is a companion to The ‘New’ Time in Painting, which examines the impact that changing concepts of time had on painting, particularly in the 20th century.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2018

We welcome your comments on this article

End Notes for Part 4

146. For this reason, too, photographs could awaken some artists to the appeal of previously unappreciated subjects. Julia Margaret Cameron’s sensitive photos of men like Carlyle and Tennyson reminded artists of the potential poetry of an old face, leading to an upsurge in paintings of these subjects, sometimes using photography as an aid (Maas, op cit at 200).

147. Feldman, E B, Varieties of Visual Experience, Prentice Hall Inc, New York, 4 edn 1992 at 432, 438.

148. Pearsell, R, Tell Me, Pretty Maiden: The Victorian and Edwardian Nude, Webb and Bower, Exeter 1981 at 152.

149. Dennis, K, Art/Porn; A History of Seeing and Touching, Berg Publishers, 2009.

150. Frizot, op cit at 270; Nead, op cit at 172. One is reminded of Benjamin’s analysis that a painter (as “magician”) increases the distance between viewer and object by virtue of her/his authority. A photographer (as “surgeon”) diminishes the distance by penetrating the object (Benjamin, op cit).

151. It is interesting that in Japan, too, the erotic woodblock prints (shunga)were also largely replaced by photography in the late nineteenth century.

152. Waller, S, The Invention of the Model: Artists and Models in Paris 1830-1870, Aldgate Publishing, Aldershot, 2006 at 74; Farwell, B, “Courbet’s ‘Baigneuses’ and the Rhetorical Feminine Image” in in Hess and Nochlin, L, Woman as Sex Object, Thames and Hudson, London, 1971 at 79.

153. McCauley, op cit at 172; Needham, G, “Manet, ‘Olympia’ and Pornographic Photography” in Hess and Nochlin, Woman as Sex Object, Thames and Hudson, London, 1971 at 80-90.

154. Needham, op cit at 83.

155. Spate, op cit at 195.

156. Scharf, op cit at 206.

157. Vaizey, op cit at 26.

158. Perhaps it was not so odd that it looked frozen, really, as it was also based on a wax model (Vaizey, op cit at 27).

159. Maas, op cit at 207. Similarly Meissonnier’s Friedland, 1807 (1875) is a full pelt cavalry charge magically frozen in time, every bunched muscle and flying hoof – and every stalk of ripening wheat – captured with an unlikely precision (King, R, The Judgment of Paris, Walter & Co, New York, 2006 at 345).

160. Scharf, op cit at 206.

161. Scharf, op cit at 205.

162. Scharf, op cit at 231.

163. It has also been suggested, rather unconvincingly, that Caillebotte’s Floor-scrapers (1875) may show the influence of multiple pose photography of the sort popularised by Muybridge and Marey: Varnedoe, (Caillebotte) op cit at 55.

164. Szarowski, The Photographer’s Eye, Little Brown & Co, 1980.

165. Kosinski, op cit at 31. In one sense, these series paintings represent an extreme development of the traditional depiction of the four seasons, or the past, present and the future. During the nineteenth century, Millet revived this tradition in works such as The Four Times of Day and The Four Seasons. Johnson suggests that Millet was influenced by Japanese woodblock series such as 100 Views of Famous Places in Edo (Johnson, D, op cit at 94). However these, unlike Monet’s series, depict different subject matters, whereas the whole point of Monet’s series was to depict ostensibly the same subject matter.

166. Spate, op cit at 171.At a serial exhibition of the Rouen Cathedral paintings, one writer imagined a “perfect equivalence of art and phenomenon – a lasting vision not of twenty, but a hundred, a thousand, a million states of the eternal cathedral in the immense cycles of the sun” (Spate, op cit at 230)

166A. The full quote is: "The imitator is a poor kind of creature. If the man who paints only the tree, or flower, or other surface that he sees before him were an artist, the king of artists would be a photographer. It Is for the artist to something beyond this; in portrait painting, to put on canvas something more than the face the model wears for that one day; to paint the man, in short, as well as his features" (Letter to The World, 22 May 1878, reproduced in Whistler, J M, "The Red Rag" in The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, various edns).

167. Rubin, op cit at 43.

168. Cited in Hendricks, op cit at 206.

169. Cited in Lewis, J, Rowland Hilder - Painter of the English Landscape, Antique Collectors’ Club, 1987 at 120-122. It also sometimes suggested that this makes photographically-based paintings easy to detect, because this process “almost invariably drains the life out of an image” (eg McDonald, J, “Free spirit says it all with the stroke of a pen”, Sydney Morning Herald, Spectrum May 23/24, 2009, at 15). However, this view is largely unverifiable, in much the same way as a belief that you’ve never been tricked by a confidence trickster. Furthermore, an artist that uses photographs literally is likely to be one who wants a literal image – the paintings may appear drained of life not because they are based on a photograph, but because precision was more important to the artist than artistic effect.

169A. Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, "Photography", The London Quarterly Review, No 101, April 1857, at 442. See also the useful article by James M McCardle, "Contradiction"

https://onthisdateinphotography.com/2018/02/08/february-8-2/

170. Clark, T J, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers, Alfred A Knopf, New York, 1985 at 10.

171. The painting abandoned traditional European one-point perspective in favour of a series of vanishing points that gave the thousands of spectators the impression of walking into the picture. A lateral multiplication of viewpoints also appears in Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day. For that matter, of course, it also appears in Raphael’s School of Athens (1510), demonstrating that the effect is not necessarily photographic.

172. Pre-Raphaelites such as Rossetti, Millais and Ford Madox Brown used cut-out photographic figures in their compositional preparations. Like Eakins they were sometimes criticised for missing the “larger picture” because of an undue concern with getting all the small local details exactly right. For the symbiotic relationship between photography and the pre-Raphaelites, see Waggoner et al, "The Pre-Raphaelite Lens; British Photography and Painting 1848-1875", Exh Cat, National Gallery of Art, London, 2011.

173. Smith suggests that this combination of optical fidelity with an imaginary set up intensified the artificiality of the painting (Smith, L, Victorian Photography, Painting and Poetry – the Enigma of Visibility in Ruskin, Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York, 1995 at 97).

174. Cited in Brassai, Picasso and Co, London, Thames and Hudson, London, 1967. The essayist and judge Oliver Wendell Holmes expressed in exaggerated form the way that photographs of the material world seemed to eclipse or even replace their subjects: “Form is henceforth divorced from matter. In fact, matter as a visible object is of no great use any longer, except as the mould on which form is shaped. Give us a few negatives of a thing worth seeing, taken from different points of view, and that is all we want of it. Pull it down or burn it up, if you please…Matter in large masses must always be fixed and dear; form is cheap and transportable. We have got the fruit of creation now, and need not trouble ourselves with the core.” (Solnit, R, “The Annihilation of Time and Space”, New England Review, Vol 24 No 1 (Winter 2003) 5.

175. McPherson, op cit at 6.

176. Similarly, Matisse would later argue that the invention of photography released painting from any need to copy nature, but this was in 1909 (Spurling, H, Matisse the Master, Penguin Books, London, 2005 at 26).

177. Japonisme, with its bold outlines and flat blocks of colour, also offered one way out of this impasse for some artists who were seeking to represent figures, events and actions without adherence to photographic exactness (Sweetman, op cit at 184).

178. Eggum, op cit at 41.

179. Vaizey, op cit at 54.

180. Spurling, op cit at 148.

181. Eggum, op cit at 45. Munch is an interesting example of an artist that was a keen, almost obsessive, user of photography in his life and art, yet went out of his way to distinguish the finished product from its sources. For example, in a portrait of Ibsen, he used photographs as the start point, transferred it to a lithographic stone, then transferred the lithograph to the canvas as the basic drawing for his painting. In this way, he felt able to achieve an artistic distance from the photograph through its progressive abstraction (op cit at 72).

181A. Denys Sutton, André Derain, Phaidon, London, 1959 at 20; cited in Sue Roe, In Montmartre; Picasso, Matisse and Modernism in Paris 1900-1910, Fig Tree, London, 2014 at 124.

182. Sontag, S, On Photography, Penguin Books, Middlesex, 1977 at 94; Galassi, op cit.

183. Cited in Vaizey, op cit at 11.

184. Sontag, op cit at 186. Putting this distinction into practice would necessarily be a subjective decision by every artist.

185. Maurice Denis had said that a painting, “before it is a … naked woman.. is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order (Vaizey, op cit at 49). However, the context, as it happens, was quite different. Denis was trying to take painting back to a kind of heraldic flatness (Hughes (Shock), op cit at 14).

186. Flam, J D, Matisse on Art, University of California Press, 1978 at 72. Matisse’s manifestly flat Harmony in Red (1908) is a good example.

187. Or of individual stereoscopic prints which only acquired a 3-D effect when viewed together,

188. Though the use of magnesium flashes evidently did not become common till the 1870s (King, op cit at 108).

189. Manet’s flatness has also, of course, been attributed to the influence of Japanese woodblock prints. As with the previous discussion about cropping, this is not necessarily an “either/or” situation, and it is possible that the two influences were mutually reinforcing.

190. To critics such as Zola, this meant that portraits remained too dependent on past models and were often as devoid of life as waxworks (McPherson, op cit at 7).

191. Renoir J, Renoir My Father, Collins, London, 1962 at 169.

192. Letter to his brother Theo, 20 Sept 1889: http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/

193. McPherson, op cit at 9.

193A. Van Gogh believed that there was some sort of mystical unity between artists, poets and the stars. In addition to the stars actually depicted in the background, he intended the brightness of Boch's head illuminated against the rich blue background would itself produce the effect of a star in the depths of an azure sky: Letter to his brother Theo 18 August 1888: http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/

194. McPherson, op cit at 9, 12; McCauley, op cit at 202. More direct types of manipulation were carried out by artists like Schiele, who sometimes painted over and otherwise manipulated photographic images of himself (Vaizey, op cit at 29).

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2018

Back to Pt 1: Initial impacts

Back to Pt 2: Photography as a working aid

Back to Pt 3: Photographic effects

Citation: McCouat, P, "Early influences of photography on art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home

147. Feldman, E B, Varieties of Visual Experience, Prentice Hall Inc, New York, 4 edn 1992 at 432, 438.

148. Pearsell, R, Tell Me, Pretty Maiden: The Victorian and Edwardian Nude, Webb and Bower, Exeter 1981 at 152.

149. Dennis, K, Art/Porn; A History of Seeing and Touching, Berg Publishers, 2009.

150. Frizot, op cit at 270; Nead, op cit at 172. One is reminded of Benjamin’s analysis that a painter (as “magician”) increases the distance between viewer and object by virtue of her/his authority. A photographer (as “surgeon”) diminishes the distance by penetrating the object (Benjamin, op cit).

151. It is interesting that in Japan, too, the erotic woodblock prints (shunga)were also largely replaced by photography in the late nineteenth century.

152. Waller, S, The Invention of the Model: Artists and Models in Paris 1830-1870, Aldgate Publishing, Aldershot, 2006 at 74; Farwell, B, “Courbet’s ‘Baigneuses’ and the Rhetorical Feminine Image” in in Hess and Nochlin, L, Woman as Sex Object, Thames and Hudson, London, 1971 at 79.

153. McCauley, op cit at 172; Needham, G, “Manet, ‘Olympia’ and Pornographic Photography” in Hess and Nochlin, Woman as Sex Object, Thames and Hudson, London, 1971 at 80-90.

154. Needham, op cit at 83.

155. Spate, op cit at 195.

156. Scharf, op cit at 206.

157. Vaizey, op cit at 26.

158. Perhaps it was not so odd that it looked frozen, really, as it was also based on a wax model (Vaizey, op cit at 27).

159. Maas, op cit at 207. Similarly Meissonnier’s Friedland, 1807 (1875) is a full pelt cavalry charge magically frozen in time, every bunched muscle and flying hoof – and every stalk of ripening wheat – captured with an unlikely precision (King, R, The Judgment of Paris, Walter & Co, New York, 2006 at 345).

160. Scharf, op cit at 206.

161. Scharf, op cit at 205.

162. Scharf, op cit at 231.

163. It has also been suggested, rather unconvincingly, that Caillebotte’s Floor-scrapers (1875) may show the influence of multiple pose photography of the sort popularised by Muybridge and Marey: Varnedoe, (Caillebotte) op cit at 55.

164. Szarowski, The Photographer’s Eye, Little Brown & Co, 1980.

165. Kosinski, op cit at 31. In one sense, these series paintings represent an extreme development of the traditional depiction of the four seasons, or the past, present and the future. During the nineteenth century, Millet revived this tradition in works such as The Four Times of Day and The Four Seasons. Johnson suggests that Millet was influenced by Japanese woodblock series such as 100 Views of Famous Places in Edo (Johnson, D, op cit at 94). However these, unlike Monet’s series, depict different subject matters, whereas the whole point of Monet’s series was to depict ostensibly the same subject matter.

166. Spate, op cit at 171.At a serial exhibition of the Rouen Cathedral paintings, one writer imagined a “perfect equivalence of art and phenomenon – a lasting vision not of twenty, but a hundred, a thousand, a million states of the eternal cathedral in the immense cycles of the sun” (Spate, op cit at 230)

166A. The full quote is: "The imitator is a poor kind of creature. If the man who paints only the tree, or flower, or other surface that he sees before him were an artist, the king of artists would be a photographer. It Is for the artist to something beyond this; in portrait painting, to put on canvas something more than the face the model wears for that one day; to paint the man, in short, as well as his features" (Letter to The World, 22 May 1878, reproduced in Whistler, J M, "The Red Rag" in The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, various edns).

167. Rubin, op cit at 43.

168. Cited in Hendricks, op cit at 206.

169. Cited in Lewis, J, Rowland Hilder - Painter of the English Landscape, Antique Collectors’ Club, 1987 at 120-122. It also sometimes suggested that this makes photographically-based paintings easy to detect, because this process “almost invariably drains the life out of an image” (eg McDonald, J, “Free spirit says it all with the stroke of a pen”, Sydney Morning Herald, Spectrum May 23/24, 2009, at 15). However, this view is largely unverifiable, in much the same way as a belief that you’ve never been tricked by a confidence trickster. Furthermore, an artist that uses photographs literally is likely to be one who wants a literal image – the paintings may appear drained of life not because they are based on a photograph, but because precision was more important to the artist than artistic effect.

169A. Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, "Photography", The London Quarterly Review, No 101, April 1857, at 442. See also the useful article by James M McCardle, "Contradiction"

https://onthisdateinphotography.com/2018/02/08/february-8-2/

170. Clark, T J, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers, Alfred A Knopf, New York, 1985 at 10.

171. The painting abandoned traditional European one-point perspective in favour of a series of vanishing points that gave the thousands of spectators the impression of walking into the picture. A lateral multiplication of viewpoints also appears in Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day. For that matter, of course, it also appears in Raphael’s School of Athens (1510), demonstrating that the effect is not necessarily photographic.

172. Pre-Raphaelites such as Rossetti, Millais and Ford Madox Brown used cut-out photographic figures in their compositional preparations. Like Eakins they were sometimes criticised for missing the “larger picture” because of an undue concern with getting all the small local details exactly right. For the symbiotic relationship between photography and the pre-Raphaelites, see Waggoner et al, "The Pre-Raphaelite Lens; British Photography and Painting 1848-1875", Exh Cat, National Gallery of Art, London, 2011.

173. Smith suggests that this combination of optical fidelity with an imaginary set up intensified the artificiality of the painting (Smith, L, Victorian Photography, Painting and Poetry – the Enigma of Visibility in Ruskin, Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York, 1995 at 97).

174. Cited in Brassai, Picasso and Co, London, Thames and Hudson, London, 1967. The essayist and judge Oliver Wendell Holmes expressed in exaggerated form the way that photographs of the material world seemed to eclipse or even replace their subjects: “Form is henceforth divorced from matter. In fact, matter as a visible object is of no great use any longer, except as the mould on which form is shaped. Give us a few negatives of a thing worth seeing, taken from different points of view, and that is all we want of it. Pull it down or burn it up, if you please…Matter in large masses must always be fixed and dear; form is cheap and transportable. We have got the fruit of creation now, and need not trouble ourselves with the core.” (Solnit, R, “The Annihilation of Time and Space”, New England Review, Vol 24 No 1 (Winter 2003) 5.

175. McPherson, op cit at 6.

176. Similarly, Matisse would later argue that the invention of photography released painting from any need to copy nature, but this was in 1909 (Spurling, H, Matisse the Master, Penguin Books, London, 2005 at 26).

177. Japonisme, with its bold outlines and flat blocks of colour, also offered one way out of this impasse for some artists who were seeking to represent figures, events and actions without adherence to photographic exactness (Sweetman, op cit at 184).

178. Eggum, op cit at 41.

179. Vaizey, op cit at 54.

180. Spurling, op cit at 148.

181. Eggum, op cit at 45. Munch is an interesting example of an artist that was a keen, almost obsessive, user of photography in his life and art, yet went out of his way to distinguish the finished product from its sources. For example, in a portrait of Ibsen, he used photographs as the start point, transferred it to a lithographic stone, then transferred the lithograph to the canvas as the basic drawing for his painting. In this way, he felt able to achieve an artistic distance from the photograph through its progressive abstraction (op cit at 72).

181A. Denys Sutton, André Derain, Phaidon, London, 1959 at 20; cited in Sue Roe, In Montmartre; Picasso, Matisse and Modernism in Paris 1900-1910, Fig Tree, London, 2014 at 124.

182. Sontag, S, On Photography, Penguin Books, Middlesex, 1977 at 94; Galassi, op cit.

183. Cited in Vaizey, op cit at 11.

184. Sontag, op cit at 186. Putting this distinction into practice would necessarily be a subjective decision by every artist.

185. Maurice Denis had said that a painting, “before it is a … naked woman.. is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order (Vaizey, op cit at 49). However, the context, as it happens, was quite different. Denis was trying to take painting back to a kind of heraldic flatness (Hughes (Shock), op cit at 14).

186. Flam, J D, Matisse on Art, University of California Press, 1978 at 72. Matisse’s manifestly flat Harmony in Red (1908) is a good example.

187. Or of individual stereoscopic prints which only acquired a 3-D effect when viewed together,

188. Though the use of magnesium flashes evidently did not become common till the 1870s (King, op cit at 108).

189. Manet’s flatness has also, of course, been attributed to the influence of Japanese woodblock prints. As with the previous discussion about cropping, this is not necessarily an “either/or” situation, and it is possible that the two influences were mutually reinforcing.

190. To critics such as Zola, this meant that portraits remained too dependent on past models and were often as devoid of life as waxworks (McPherson, op cit at 7).

191. Renoir J, Renoir My Father, Collins, London, 1962 at 169.

192. Letter to his brother Theo, 20 Sept 1889: http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/

193. McPherson, op cit at 9.

193A. Van Gogh believed that there was some sort of mystical unity between artists, poets and the stars. In addition to the stars actually depicted in the background, he intended the brightness of Boch's head illuminated against the rich blue background would itself produce the effect of a star in the depths of an azure sky: Letter to his brother Theo 18 August 1888: http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/

194. McPherson, op cit at 9, 12; McCauley, op cit at 202. More direct types of manipulation were carried out by artists like Schiele, who sometimes painted over and otherwise manipulated photographic images of himself (Vaizey, op cit at 29).

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2018

Back to Pt 1: Initial impacts

Back to Pt 2: Photography as a working aid

Back to Pt 3: Photographic effects

Citation: McCouat, P, "Early influences of photography on art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home