the adventures of nadar

PHOTOGRAPHY, BALLOONING, INVENTION AND THE IMPRESSIONISTS

By Philip McCouat See reader comments on this article

A Renaissance man of Paris

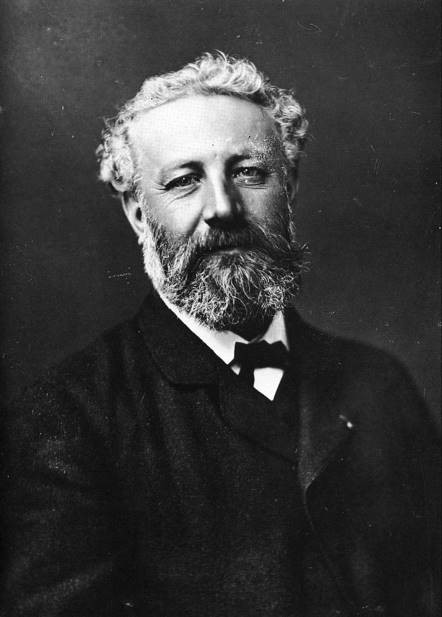

In this article, we’ll be looking at the life of a truly extraordinary, multi-talented nineteenth-century Frenchman, whose name – Gaspard-Félix Tournachon – you may never have heard of.

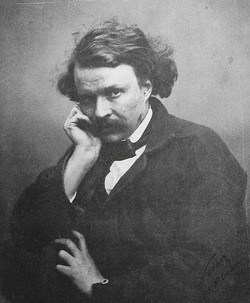

Tournachon was born in 1820 in Paris. Under the pseudonym “Nadar”, he would become a prolific French caricaturist and writer, the most famous photographer of his era, a national hero for his ballooning exploits, an inveterate innovator, a friend of the Impressionists and a flamboyant showman.

His impressive set of achievements was reflected in his own extraordinary appearance. He was memorably described as “a sort of giant… a figure with immensely long legs, exceedingly long arms, extensive torso, and on top of all this, a head of shocking red hair surmounted by a pair of large, intelligent, darting eyes, full of wild lights…” [1].

Tournachon was born in 1820 in Paris. Under the pseudonym “Nadar”, he would become a prolific French caricaturist and writer, the most famous photographer of his era, a national hero for his ballooning exploits, an inveterate innovator, a friend of the Impressionists and a flamboyant showman.

His impressive set of achievements was reflected in his own extraordinary appearance. He was memorably described as “a sort of giant… a figure with immensely long legs, exceedingly long arms, extensive torso, and on top of all this, a head of shocking red hair surmounted by a pair of large, intelligent, darting eyes, full of wild lights…” [1].

Nadar, as we shall call him, owed much of his success to his own irrepressible personality. Many who knew him commented on his boyish enthusiasm, endlessly cheery egoism, constantly inquiring attitude, his ingenuity in finding unexpected solutions, and his determination in putting those solutions into practice [2]. Crucially, he also had an extraordinary aptitude for friendship. He seemed to know everyone who was somebody in Paris. He once claimed that he knew 10,000 people, and probably this claim is not as exaggerated as it first sounds.

Nadar thrived on challenges. Nothing inspired him more that someone telling him that something he dreamed of doing was impossible ¬ his motto was that “nothing is easier than what was done yesterday; nothing is more impossible than what will be done tomorrow”[3].

So, armed with all these promising attributes, let’s see how he fared.

Nadar thrived on challenges. Nothing inspired him more that someone telling him that something he dreamed of doing was impossible ¬ his motto was that “nothing is easier than what was done yesterday; nothing is more impossible than what will be done tomorrow”[3].

So, armed with all these promising attributes, let’s see how he fared.

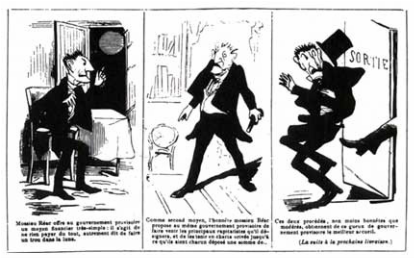

Nadar the journalist and caricaturist

After his father’s early death, Nadar earned his tuition fees for medical school by writing theatre criticism for newspapers. As his interest in publishing grew, he gave up medicine for journalism, working for several publications in different capacities including freelance contributor, editor and publisher. The financial returns did not match his entrepreneurial ambitions and he later turned to caricatures, satirical cartoons and even the new innovation, the comic strip [4]. He also tried his hand at writing books; he would eventually produce fifteen or so, together with hundreds of articles over his lifetime.

About this time, he had adopted his distinctive pseudonym. Reflecting the biting nature of his caricatures, his surname Tournachon was punningly changed to Tournadar (“tourne à dar” = the one the one who stings or twists the dart”). Dropping the first syllable left “Nadar”, and it was by this single word that he became universally known for the rest of his life. (Or perhaps not universally. In one quixotic venture in 1848 Nadar marched with a French legion -- under the name Nadarsky(!)—in an ill-fated attempt to liberate Poland, and spent a few weeks in an internment camp before getting back to Paris [5].

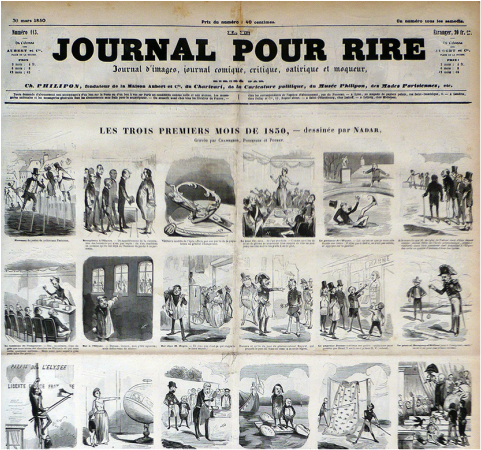

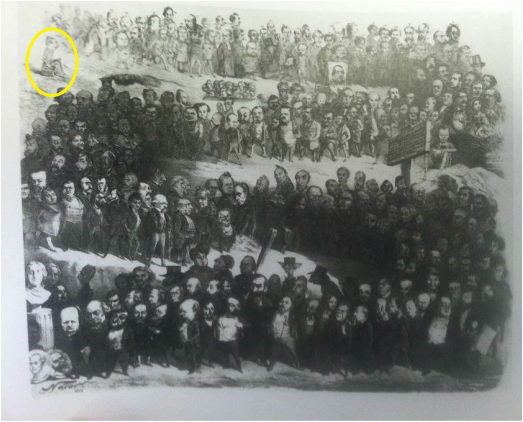

Nadar’s first real breakthrough came in 1851, when he conceived the idea of a comprehensive visual record of the 1,000 most prominent Parisians in painting, music, theatre, opera and literature. With typical chutzpah, he called it the Panthéon Nadar. The first instalment, covering caricatures of 300 personalities, was published in 1854 (Fig 6). There was no difficulty in getting sitters because, as Nadar pointed out, “[he] had friendly relations – intimate or benevolent – with all the illustrious people of the time”, including George Sand, Balzac and Victor Hugo [6].

Faced with the task of fitting so many people onto one sheet, he improvised by presenting them in a serpentine collage of caricatures, giving them grotesquely enlarged heads and tiny shrunken bodies – in a similar style to much political cartooning of today. Reflecting his republican sympathies, he placed the Emperor Napoleon III sitting rather alone and desolate at the end of the queue.

Nadar the portrait photographer

The Panthéon made Nadar a celebrity, but not a rich one. Almost by accident, however, it plunged him into the newly developing field of photography. It was an area in which he was already interested -- he had originally financed his brother Adrian’s photography business. Nadar found that photography provided an ideal way to keep track of all his Panthéon subjects as they aged, and to keep it up to date for future instalments. By avoiding the need for long sitting times, it also had the virtue of not exhausting the goodwill of his models for too long [7].

It was also convenient from another angle -- the invention of the wet-collodion plate, with its much faster exposure time, allowed him to work in his own apartment, using an upstairs room with skylights as his studio, and preparing and developing his own pictures with a small chemistry apparatus [8].

Around this time, photography was booming, and it rapidly became Nadar’s main interest, one which would engage him virtually for the rest of his life. Through a combination of talent, personality and entrepreneurial skills, he would eventually become one of the most celebrated of the more than three hundred professional photographers who were working in Paris in the 1860s [9].

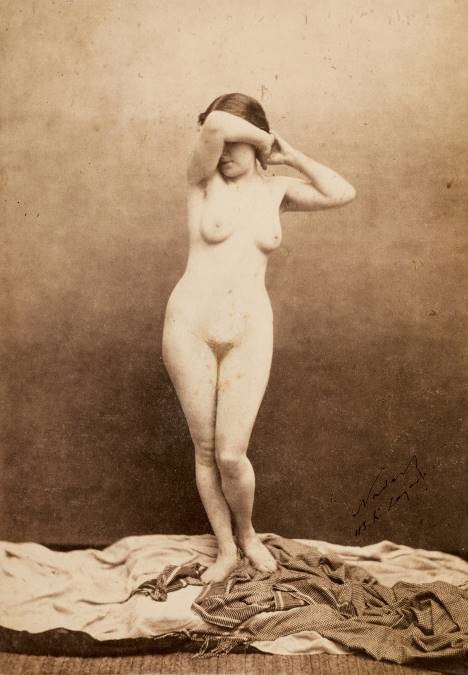

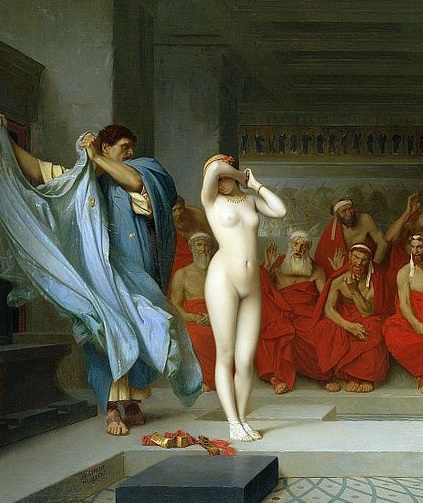

Most of the business for photographers consisted either of formal portraits or the sort of “academic” nude photos that were churned out as studies for artists. Nadar engaged in both genres -- Gérôme, for example specifically commissioned Nadar to provide a nude study for the painter’s Phryné before the Areopagus.

It was also convenient from another angle -- the invention of the wet-collodion plate, with its much faster exposure time, allowed him to work in his own apartment, using an upstairs room with skylights as his studio, and preparing and developing his own pictures with a small chemistry apparatus [8].

Around this time, photography was booming, and it rapidly became Nadar’s main interest, one which would engage him virtually for the rest of his life. Through a combination of talent, personality and entrepreneurial skills, he would eventually become one of the most celebrated of the more than three hundred professional photographers who were working in Paris in the 1860s [9].

Most of the business for photographers consisted either of formal portraits or the sort of “academic” nude photos that were churned out as studies for artists. Nadar engaged in both genres -- Gérôme, for example specifically commissioned Nadar to provide a nude study for the painter’s Phryné before the Areopagus.

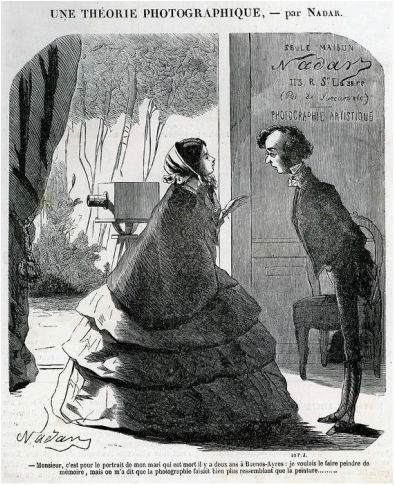

But by far the greatest part of Nadar’s business was in making portraits. Among the general population, photography was still regarded as almost magic and there was little understanding of how it actually worked. Nadar once published a cartoon, allegedly based on a real-life incident, in which a woman who has come to his studio asks him to do a portrait of her husband who died two years previously, as she had heard that photographs give a better resemblance than painting.

Nadar’s portraits were distinctive. He believed that while photography could be practised by “any imbecile’, what could not be learned was an artistic appreciation for the effects produced by different and combined sources of light. What could be learned even less was “the moral understanding of the subject – that instant tact which puts you in communication with the model… and enables you to give… the most convincing and sympathetic likeness, an intimate resemblance” [10].

So, in contrast to the stiff, formally-posed portraits that were common at the time, Nadar posed his subjects in natural, relaxed positions, with sympathetic, atmospheric lighting. He became famous (and wealthy) for his ability to capture the character of his sitters, not just their physical resemblance. His portraits intimes were typically full face, searchingly frank, without any of the conventional trappings or drapes or formal costumes [11]. They pointed the way for photography in the future.

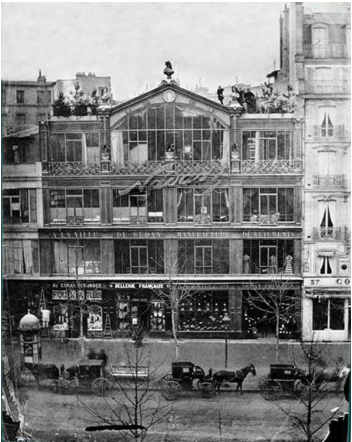

Nadar eventually established himself in a dramatic new two-storey studio at 35 Boulevard des Capucines. Both the exterior and interior of the studio were flaming red, its rooms decorated with works of art. Nadar often wore a resplendent red velvet robe to greet his special clients (with whom he would often dine before the sitting), and his name was written in an illuminated running red flourish over a 15 metre expanse across the front of the building. Not surprisingly, the building itself became a local landmark and a favourite meeting place for the cultural intelligentsia of Paris.

So, in contrast to the stiff, formally-posed portraits that were common at the time, Nadar posed his subjects in natural, relaxed positions, with sympathetic, atmospheric lighting. He became famous (and wealthy) for his ability to capture the character of his sitters, not just their physical resemblance. His portraits intimes were typically full face, searchingly frank, without any of the conventional trappings or drapes or formal costumes [11]. They pointed the way for photography in the future.

Nadar eventually established himself in a dramatic new two-storey studio at 35 Boulevard des Capucines. Both the exterior and interior of the studio were flaming red, its rooms decorated with works of art. Nadar often wore a resplendent red velvet robe to greet his special clients (with whom he would often dine before the sitting), and his name was written in an illuminated running red flourish over a 15 metre expanse across the front of the building. Not surprisingly, the building itself became a local landmark and a favourite meeting place for the cultural intelligentsia of Paris.

Nadar left most of the general run of portraits to his assistants, reserving for himself the most distinguished sitters. Over the years, the gallery of portraits that he built up would become an “incomparable visual museum of the great names of his time”, making him “a personality among personalities and the most famous photographer of the century in France” [12]. Everyone was there -- Flaubert, Jules Verne (Fig 11), Baudelaire (who hated photography), Dumas, Victor Hugo, Rossini, Berlioz, Meyerbeer, Sarah Bernhardt (Fig 12), George Sand, Wagner, Liszt, Gounod, Doré, Delacroix, Millet. One notable omission was Balzac who, in a seeming reversion to primitivism, feared that the camera might “steal his soul”.

The noted biographer, Richard Holmes, has commented on the huge impact of a viewing of Nadar’s vast body of work. “Here was the next literary and artistic generation after Shelly and Byron, suddenly brought back to life – their hairstyles, their wrinkles, their buttoned jackets, scuffed shoes, watch chains or necklaces, frayed shirt cuffs, smile lines, worry lines -- in a way that made them almost completely contemporary… These people would never be lost in ‘history’. Here they were, alive, like us, flesh and blood and touched by the marks of life” [13].

This effect was magnified by Nadar’s practice of taking photos of people over a long period in their life, providing an invaluable biographical record. For Holmes, Nadar’s photography “made possible a whole new kind of biography”.

This effect was magnified by Nadar’s practice of taking photos of people over a long period in their life, providing an invaluable biographical record. For Holmes, Nadar’s photography “made possible a whole new kind of biography”.

Nadar the balloonist…

Photography, while absorbing, was by no means Nadar’s only interest. Along with several of his friends, Including Jules Verne and Victor Hugo, he was fascinated by the idea of human flight. Accordingly, during the 1850s, Nadar enthusiastically began hot-air ballooning.

Ballooning offered an escape from the cares of the world. He described the sensation of ascending as a ”free, calm, levitating into the silent immensity of welcoming and beneficent space”, which presented “an admirable spectacle…. an immense carpet without borders… what purity of lines, what extraordinary clarity of sight… with the exquisite impression of a marvellous, ravishing cleanliness!” [14].

Ballooning offered an escape from the cares of the world. He described the sensation of ascending as a ”free, calm, levitating into the silent immensity of welcoming and beneficent space”, which presented “an admirable spectacle…. an immense carpet without borders… what purity of lines, what extraordinary clarity of sight… with the exquisite impression of a marvellous, ravishing cleanliness!” [14].

… and the invention of aerial photography

For Nadar, the sublime views presented from the balloon virtually demanded photography -- they were an imperative and intense “invitation to the lens” [15]. He soon set about conducting the first experiments with aerial photography from a small balloon tethered above an apple orchard in the village of Petit-Bicêtre, outside Paris [16].

His initial problem was to keep the balloon sufficiently stable to be used as a platform for photography. This was solved by operating only in calm weather, by fully inflating the balloon so that the cables were ultra-tight, and by reducing shutter speed. But, even so, Nadar found that, time after time, all he could achieve were images of black soot. He eventually discovered, after many trials, that on ascent the balloon’s escape valve, which normally needed to be open, was expelling excess hydrogen gas which contaminated the developing plates. The solution became clear -- keep the valve closed and fit a thick insulating tent [17]. Nadar’s excitement at seeing the first successful, tentative image to emerge is evident in his own description of the moment:

“It is only a simple positive on glass, very feeble in this so hazy atmosphere, [but] it is impossible to deny it. There beneath me are the only three houses of the small town, the farmhouse, the inn and the police station… One can distinguish perfectly on the road a tapestry maker whose cart stopped before the balloon, on the tiles of the roof, the two white doves that had just landed there. I was right then!” [18].

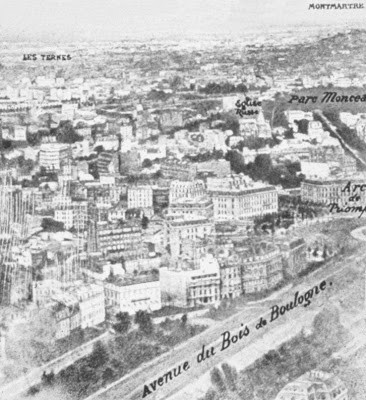

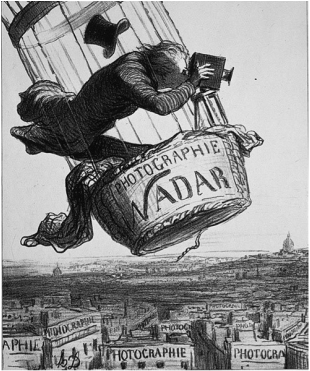

Those photos, dated at about 1858, have unfortunately been lost, and his first photos available to us are of Paris, from a much higher altitude, taken some time later (Fig 13) [18A]. It was this achievement that inspired his friend Daumier to publish his cartoon, Nadar elevating Photography to the level of Art (Fig 14), a melodramatic, tongue-in-cheek depiction of Nadar taking hair-raising risks to take a photograph from the tiny wildly swinging gondola of his balloon. Later, his friend Jules Verne created a fictionalised Nadar as the character Michael “Ardan” in Verne’s science fiction novel From the Earth to the Moon {1865), casting him as one of the astronauts who were to “carry into outer-space all the resources of art, science and industry”.

His initial problem was to keep the balloon sufficiently stable to be used as a platform for photography. This was solved by operating only in calm weather, by fully inflating the balloon so that the cables were ultra-tight, and by reducing shutter speed. But, even so, Nadar found that, time after time, all he could achieve were images of black soot. He eventually discovered, after many trials, that on ascent the balloon’s escape valve, which normally needed to be open, was expelling excess hydrogen gas which contaminated the developing plates. The solution became clear -- keep the valve closed and fit a thick insulating tent [17]. Nadar’s excitement at seeing the first successful, tentative image to emerge is evident in his own description of the moment:

“It is only a simple positive on glass, very feeble in this so hazy atmosphere, [but] it is impossible to deny it. There beneath me are the only three houses of the small town, the farmhouse, the inn and the police station… One can distinguish perfectly on the road a tapestry maker whose cart stopped before the balloon, on the tiles of the roof, the two white doves that had just landed there. I was right then!” [18].

Those photos, dated at about 1858, have unfortunately been lost, and his first photos available to us are of Paris, from a much higher altitude, taken some time later (Fig 13) [18A]. It was this achievement that inspired his friend Daumier to publish his cartoon, Nadar elevating Photography to the level of Art (Fig 14), a melodramatic, tongue-in-cheek depiction of Nadar taking hair-raising risks to take a photograph from the tiny wildly swinging gondola of his balloon. Later, his friend Jules Verne created a fictionalised Nadar as the character Michael “Ardan” in Verne’s science fiction novel From the Earth to the Moon {1865), casting him as one of the astronauts who were to “carry into outer-space all the resources of art, science and industry”.

Le Géant: the biggest balloon in the world

Nadar was initially convinced that aerial photography would prove invaluable for surveying, mapmaking, and even military espionage. Despite the attractions of ballooning, however, a few mishaps convinced Nadar that its suitability for directed flight was limited, and that effective navigable flight would require not a balloon but a heavier-than-air machine. As he himself commented, “Several abrupt descents during which, by a little fresh wind, my wicker basket crashed into trees and walls, very quickly gave me something to think about… If I can’t simply stop my balloon under this insignificant breeze, where the slightest increase in speed tangles my anchors, and drags me through everything, then my claim to steer it against the currents would be more than impertinent” [19].

Characteristically, he did not just dream about heavier-than-air flight. He set up a discussion and pressure group, The Society for the Encouragement of Aerial Navigation by Heavier-than-air Machines, with himself as President and Jules Verne as Secretary, and started up a specialised journal called L’Aeronaute. The initial reaction was enthusiastic, with Nadar claiming that “almost immediately there were 600 of us” [20]. Prototypes of various heavier-than-air machines were developed, including a (theoretically possible) helicopter. But Nadar soon realised that the venture would require considerable amounts of money. He therefore devised a plan to raise funds by building a balloon “of previously unheard of dimensions”. In effect, he was seeking to use this lighter-than-air technology to raise money so that his dream of heavier-than-air flight might be realised [21].

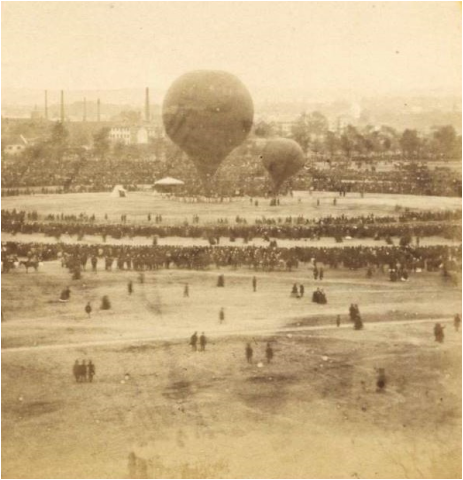

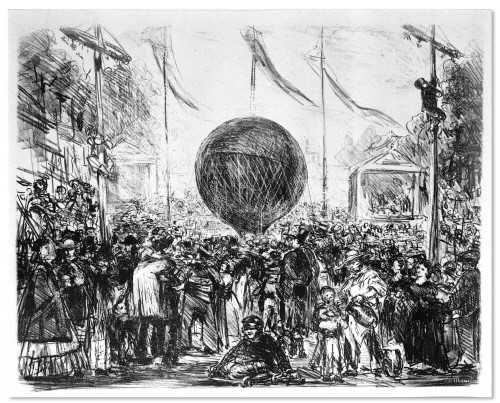

So, in 1863 he set about constructing the world’s largest hot air balloon, Le Géant. Just a few months earlier, Jules Verne had published his first novel, Five Weeks in a Balloon, in which he imagined a voyage across Africa in a giant hot-air balloon. Nadar’s real-life Le Géant outstripped even Verne’s imaginings, standing almost 200 feet high feet tall with 200,000 cu ft of hydrogen encased in a balloon that used almost 12 miles of silk. It was said that 200 women had required a month to sew it all together.

The balloon’s wicker-work gondola was the size of a small cottage, and was equipped with a photographic laboratory, a refreshment room, a lavatory, and a billiard table [22]. Nadar claimed that it was capable of lifting up to 45 artillery soldiers [23]. Visible for miles, it was a truly fantastic sight, and attracted outstanding publicity [24].

Characteristically, he did not just dream about heavier-than-air flight. He set up a discussion and pressure group, The Society for the Encouragement of Aerial Navigation by Heavier-than-air Machines, with himself as President and Jules Verne as Secretary, and started up a specialised journal called L’Aeronaute. The initial reaction was enthusiastic, with Nadar claiming that “almost immediately there were 600 of us” [20]. Prototypes of various heavier-than-air machines were developed, including a (theoretically possible) helicopter. But Nadar soon realised that the venture would require considerable amounts of money. He therefore devised a plan to raise funds by building a balloon “of previously unheard of dimensions”. In effect, he was seeking to use this lighter-than-air technology to raise money so that his dream of heavier-than-air flight might be realised [21].

So, in 1863 he set about constructing the world’s largest hot air balloon, Le Géant. Just a few months earlier, Jules Verne had published his first novel, Five Weeks in a Balloon, in which he imagined a voyage across Africa in a giant hot-air balloon. Nadar’s real-life Le Géant outstripped even Verne’s imaginings, standing almost 200 feet high feet tall with 200,000 cu ft of hydrogen encased in a balloon that used almost 12 miles of silk. It was said that 200 women had required a month to sew it all together.

The balloon’s wicker-work gondola was the size of a small cottage, and was equipped with a photographic laboratory, a refreshment room, a lavatory, and a billiard table [22]. Nadar claimed that it was capable of lifting up to 45 artillery soldiers [23]. Visible for miles, it was a truly fantastic sight, and attracted outstanding publicity [24].

Such was the public excitement generated by Nadar’s extravagant new creation that more than 500,000 people, about a third of the population of Paris, crowded onto the Champ-de-Mars to witness its maiden voyage. A military band played, the gondola was towed into place by four white horses, and the paying passengers and crates of champagne were loaded [25]. The actual flight, however, proved a little disappointing. Nadar describes how they were dragged aloft at nearly the normal speed of express train, until a valve line malfunction forced their premature descent into a bog only 25 miles away, a far cry from the original intention to travel across Europe [26].

Undaunted (as always), Nadar organised a second flight two weeks later. Le Géant successfully floated 400 miles in 14 hours, reaching Hanover, but was then hit by strong winds, could not re-ascend and slowly fell to earth. Unfortunately, it could not stop moving, and continued to bound across woods and fields, tearing through trees and bouncing off the earth like an gigantic India rubber ball, narrowly avoiding a collision with a railway train and eventually bursting. The passengers, who had either jumped or been thrown out, “were strewn over the ground like so many felled apples” [27].

Amazingly, though there were a number of injuries among the passengers and crew, including Nadar himself and his young wife. no-one was killed. Le Géant would go on to make further flights, attracting large crowds wherever it went. (In fact, the need for crowd control inspired Nadar to invent mobile crowd barriers to keep them at a sale distance [28]). Nadar enthusiastically exploited its publicity value by writing a potboiler account of the incident [29], while at the same time highlighting that heavier-than-air machines were really the way of the future.

So far as being a source of finance, the Le Géant venture turned out to be a failure. But, as Richard Holmes points out, it had in the process elevated and transformed the very idea of travel itself [30].

Undaunted (as always), Nadar organised a second flight two weeks later. Le Géant successfully floated 400 miles in 14 hours, reaching Hanover, but was then hit by strong winds, could not re-ascend and slowly fell to earth. Unfortunately, it could not stop moving, and continued to bound across woods and fields, tearing through trees and bouncing off the earth like an gigantic India rubber ball, narrowly avoiding a collision with a railway train and eventually bursting. The passengers, who had either jumped or been thrown out, “were strewn over the ground like so many felled apples” [27].

Amazingly, though there were a number of injuries among the passengers and crew, including Nadar himself and his young wife. no-one was killed. Le Géant would go on to make further flights, attracting large crowds wherever it went. (In fact, the need for crowd control inspired Nadar to invent mobile crowd barriers to keep them at a sale distance [28]). Nadar enthusiastically exploited its publicity value by writing a potboiler account of the incident [29], while at the same time highlighting that heavier-than-air machines were really the way of the future.

So far as being a source of finance, the Le Géant venture turned out to be a failure. But, as Richard Holmes points out, it had in the process elevated and transformed the very idea of travel itself [30].

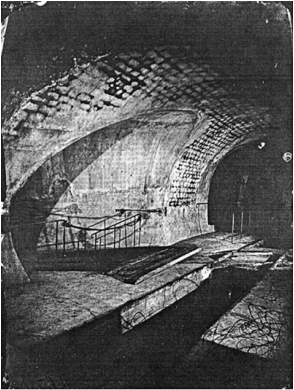

The invention of underground photography

Not content with photographing from the air, Nadar had also begun on a novel project to photograph underground, using only electric light. This would pose some considerable challenges. Photography had always been associated with light – its very name means “a drawing of light” -- and here was Nadar saying that he could take photographs without any natural light at all.

As it happened, Paris had two underground sites that were the object of great public interest. The first was its relatively advanced sewerage system, with its hundreds of kilometres of underground tunnels and storm drains. During Nadar’s time, these were actually a tourist attraction where people took adventurous boat rides by torchlight [31].

The second site was Paris’ elaborate system of underground catacombs, which contained the bones of over six million people, macabrely stacked and complete with funeral monuments, inscriptions, and displays. These too had become a tourist attraction, with the demand to see them being so great that special permission was required to visit them. They were only open four times a year, each time attracting 400-500 visitors [32].

The commercial attractions of photographing these sites were obvious to Nadar. There was a large demand to see these places, but only limited access. And the promise of being the first to produce photographs using only artificial light would be a notable achievement.

As Nadar soon discovered, however, there were forbidding logistical problems with the venture. Enormous Bunsen batteries and other bulky equipment had to be transported and used, and weeks of experimentation had to go into modulating the light. The first photographs taken in the sewers, for example, took up to 18 minutes’ exposure.

As it happened, Paris had two underground sites that were the object of great public interest. The first was its relatively advanced sewerage system, with its hundreds of kilometres of underground tunnels and storm drains. During Nadar’s time, these were actually a tourist attraction where people took adventurous boat rides by torchlight [31].

The second site was Paris’ elaborate system of underground catacombs, which contained the bones of over six million people, macabrely stacked and complete with funeral monuments, inscriptions, and displays. These too had become a tourist attraction, with the demand to see them being so great that special permission was required to visit them. They were only open four times a year, each time attracting 400-500 visitors [32].

The commercial attractions of photographing these sites were obvious to Nadar. There was a large demand to see these places, but only limited access. And the promise of being the first to produce photographs using only artificial light would be a notable achievement.

As Nadar soon discovered, however, there were forbidding logistical problems with the venture. Enormous Bunsen batteries and other bulky equipment had to be transported and used, and weeks of experimentation had to go into modulating the light. The first photographs taken in the sewers, for example, took up to 18 minutes’ exposure.

Added to this, the surroundings were not as exciting as Nadar had hoped. He described the catacombs as “a place everyone wants to see but no one wants to see again” [33] and the sewers were disappointingly industrial. Nevertheless,after three months’ frustratingly hard work – a period which Nadar said, “I would not wish on my worst enemy, if I had one” [34] – he eventually succeeded in producing a hundred negatives.

Although rather disappointed by the quality of the prints (he had high standards), and losing a considerable amount of money in the process, he had at least achieved a goal that most other people considered to be quite impossible.

The Siege of Paris and the invention of airmail

It was in a time of great crisis that Nadar’s impressive capacity to think laterally came to the fore, in what would turn out to be one of his most useful achievements.

France’s unfortunate declaration of war on Prussia in 1870 had been followed by a succession of disastrous military defeats, culminating in the capture of Napoleon III, and by the Prussians surrounding and besieging Paris itself.

France’s unfortunate declaration of war on Prussia in 1870 had been followed by a succession of disastrous military defeats, culminating in the capture of Napoleon III, and by the Prussians surrounding and besieging Paris itself.

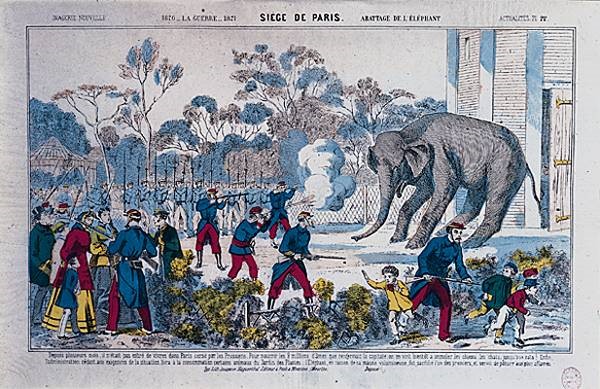

Paris, already swollen by the earlier influx of war refugees, was cut off. As the months of the siege dragged on, severe food shortages developed, forcing the Parisians to slaughter whatever animals were available. Rats, dogs, cats, horses and even zoo animals, such as the elephants Castor and Pollux, paid the price (Fig 19).

|

As Victor Hugo commented, “Our stomachs are like Noah’s Ark”. Most of the trees in the Bois de Boulogne were cut down for firewood, buildings remained unheated, carp were even culled from council ponds. Public morale hit rock bottom [35].

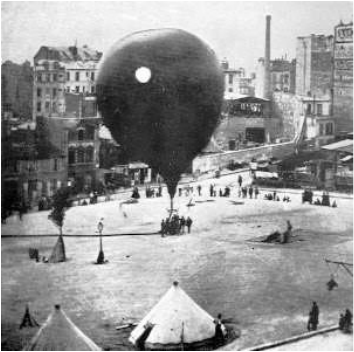

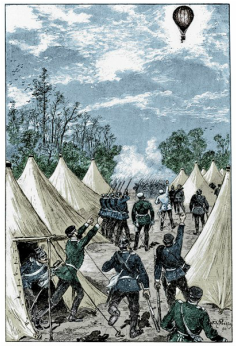

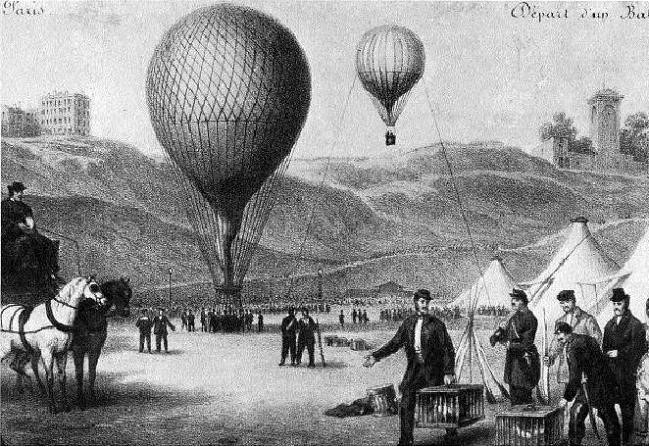

Because of the siege, effective communications with the outside world – news, military or personal correspondence -- proved to be impossible. But could balloons be the answer? Nadar certainly thought so. He had already set up the “No 1 Compagnie des Aérostiers” and established an observation-balloon service in the Montmartre district, using Jules Duruof’’s veteran balloon, the Neptune. But he now suggested that balloons could be used to cross the Prussian lines, despite the risk of enemy fire, to get the mail out of Paris to the rest of the world [36]. |

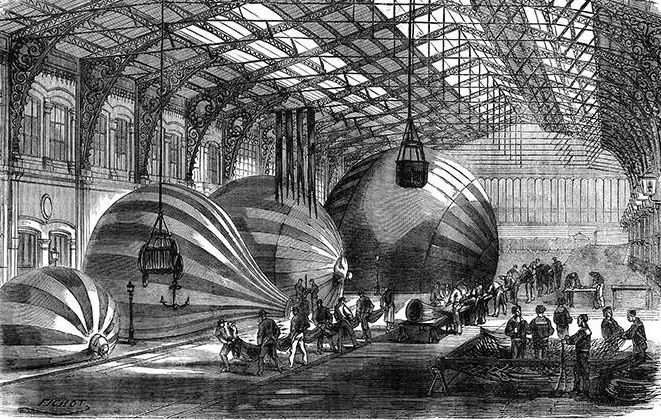

Buoyed by this success, which caused public elation in France, workshops were set up to manufacture more mail balloons (Fig 23) -- one under the direction of Nadar and the other under the direction of Eugène Godard -- and a regular mail service, “Paris Balloon Post” was set up. Over the next few months, more than 60 flights were made, with only five being captured by the Prussians, and three disappearing. Overall, over 2 million letters were delivered [37].

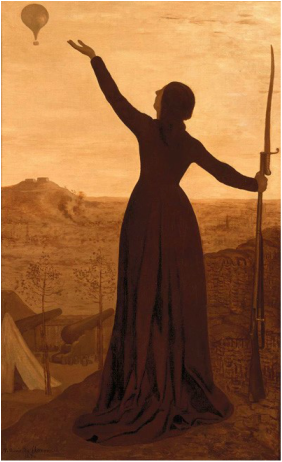

For France, it was a huge technical and propaganda triumph. The siege had been broke by a balloon. Prussian firepower had been beaten by French airpower. As the poet Théophile Gautier wrote, “The wind was our postman, the balloon was our letterbox…. With each departing aeronaut, our deepest thoughts also took flight.” Victor Hugo marvelled that “One would have to be a pinhead not to recognise the huge significance of what has been achieved… By means of a simple balloon, a mere bubble of air, Paris is back in communication with the rest of the world!” Richard Holmes describes it as “the first successful civilian airlift in history” [38]. And artist Puvis de Chavannes glorified the achievement in his hugely popular The Balloon (Fig 24).

Of course, it was one thing to get the mail out. It was quite another to get mail from outside into Paris. On the outward journey it didn’t really matter where the balloon landed, as long as it was outside the Prussian area of control. But as the balloons were dependent on the direction of the wind, and could not be steered, return mail could not be sent back [39].

One suggestion was for each outward balloon to include a number of Parisian carrier pigeons. When the balloon landed, return mail could be strapped to their legs and they would then fly home to their Parisian base. This was fine as far as it went, but the drawback was that this could only handle a tiny number of messages. The ingenious solution, proposed to Nadar by an anonymous citizen, was to use a recent innovation – microphotography. Nadar described the procedure this way:

Of course, it was one thing to get the mail out. It was quite another to get mail from outside into Paris. On the outward journey it didn’t really matter where the balloon landed, as long as it was outside the Prussian area of control. But as the balloons were dependent on the direction of the wind, and could not be steered, return mail could not be sent back [39].

One suggestion was for each outward balloon to include a number of Parisian carrier pigeons. When the balloon landed, return mail could be strapped to their legs and they would then fly home to their Parisian base. This was fine as far as it went, but the drawback was that this could only handle a tiny number of messages. The ingenious solution, proposed to Nadar by an anonymous citizen, was to use a recent innovation – microphotography. Nadar described the procedure this way:

“Everyone brings to the office of outgoing mail his correspondence, written on one side only, with the recipient’s address at the top, written as clearly as possible. A special photographic centre is installed there … all the letters brought are placed alongside each other on a mobile surface, in a number to be determined, a hundred, five hundred, a thousand. A two-way mirror keeps them in place by pressing them down. This set… is immediately photographed at the minimal reduction possible…

“Instead of photographing on glass or paper, as with ordinary shots, the operation must be performed on collodion,, thanks to its lack of grain, transparency, flexibility and, above all, thinness. This micrographic image of an almost zero weight is mounted on [the bird]. Once at its destination, the counter operation: enlargement of this micrographic image of every missive, amplified to its current format, in order to be cut immediately, folded into an envelope, and addressed to each recipient” [40].

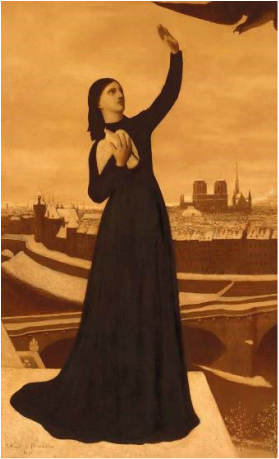

What’s more, it worked! Each homing pigeon could carry about a thousand microfilmed messages. “Our Paris, strangled by its anxiety over its absent ones,” Nadar wrote, “finally breathed.”[41]. And again, de Chavannes celebrated it in art (Fig 25).

Nadar and the Impressionists

In 1873, at the Café de Nouvelles Athènes, just off the Place Pigalle, a lively crowd of writers, artist and hangers-would customarily gather round the marble tables, arguing about painting, writing, politics and other issues of the day [42]. Two of the tables were reserved for the painters -- Manet, Degas and their friends Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, Bazille and Cézanne, among others. Together, they formed a loose-knit group of younger artists interested in shaking up the art establishment with a fresh new approach to painting.

Just how they should achieve this aim was a matter of some dispute. Most, led by Monet, Renoir, Pissarro and Degas, were keen on organising a group exhibition. Manet, on the other hand, the only one of them whose work had ever been accepted for the prestigious official Paris Salon, was not so keen; he was concerned that it would be needlessly provocative.

The majority view won out, spurred by a generous gesture by a friend of Manet. You will probably guess who it was -- none other than Nadar [43]. The two were quite close -- Manet had earlier dedicated his painting Jeune Femme en Costume Espagnol to Nadar. He had also depicted ballooning in his lithograph The Balloon and in the presence of Le Géant in the background of his View of the 1867 Exposition Universelle.

Just how they should achieve this aim was a matter of some dispute. Most, led by Monet, Renoir, Pissarro and Degas, were keen on organising a group exhibition. Manet, on the other hand, the only one of them whose work had ever been accepted for the prestigious official Paris Salon, was not so keen; he was concerned that it would be needlessly provocative.

The majority view won out, spurred by a generous gesture by a friend of Manet. You will probably guess who it was -- none other than Nadar [43]. The two were quite close -- Manet had earlier dedicated his painting Jeune Femme en Costume Espagnol to Nadar. He had also depicted ballooning in his lithograph The Balloon and in the presence of Le Géant in the background of his View of the 1867 Exposition Universelle.

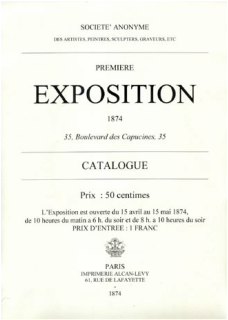

At the time, Nadar had retained possession of his former studio at 35 Boulevard des Capucines. The now-empty studio, with its blood-red hessian-lined walls, cast iron pillars, skyights and floor-to-ceiling windows, was a prime commercial site, but Nadar offered it to the group rent-free to stage the exhibition. No doubt, he relished the controversy that he felt sure would arise. By nature a stirrer, Nadar was not at all put out by the uproar the exhibition might cause [44]. Notoriety was good for business, though there is little evidence that he himself particularly embraced the group’s artistic ideals.

Eventually, a plan was agreed upon. The exhibition would be run through a sort of co-operative society, with none of the normal attributes of judges, jury or prizes. It would be named, rather awkwardly, the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes, Peintres, Graveurs etc with the group itself to be known as “les Indépendantes” [45]. The exhibiting painters also included a sole woman, Berthe Morisot, with a scattering of fashionable artists – Boudin, Bracquemond and Meissonier -- to add some credibility. Manet, though, eventually declined to participate.

Eventually, a plan was agreed upon. The exhibition would be run through a sort of co-operative society, with none of the normal attributes of judges, jury or prizes. It would be named, rather awkwardly, the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes, Peintres, Graveurs etc with the group itself to be known as “les Indépendantes” [45]. The exhibiting painters also included a sole woman, Berthe Morisot, with a scattering of fashionable artists – Boudin, Bracquemond and Meissonier -- to add some credibility. Manet, though, eventually declined to participate.

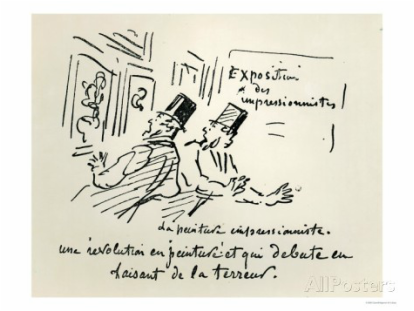

The exhibition opened to wide public interest – but even greater ridicule -- from both the public and many critics. As Sue Roe describes, “The public flocked in, screamed with horror and alerted their friends, who were also aghast. There was pandemonium” [46].

Renoir’s La Loge was ridiculed and one critic commented that Cezanne seemed “no more than a kind of madman, painting while suffering from delirium tremens”. Jokes circulated that he and many of his fellow painters accomplished their work by loading pistols with tubes of paint and discharging them at their canvases [47].

Renoir’s La Loge was ridiculed and one critic commented that Cezanne seemed “no more than a kind of madman, painting while suffering from delirium tremens”. Jokes circulated that he and many of his fellow painters accomplished their work by loading pistols with tubes of paint and discharging them at their canvases [47].

Towards recording sound and movement

Having seen how the seemingly impossible task of recording light had been achieved with photography, Nadar could see no reason why the same could not be achieved in other areas – why not record sound? Why not record movement? In retrospect, we can see that he was groping toward something that still lay far in the future – for if light, sound and movement could be recorded, we of course have the modern movie.

Nadar’s speculations as to the possibility of recording sound go back as far as 1856. In an article in Musee Francais-Anglais, he imagined a new machine called a “phonograph”, which would be an “acoustic daguerreotype, which faithfully and tirelessly reproduces all the sounds subjected to its objectivity… a box in which melodies could be caught and fixed, as the camera obscura captures ad fixes images” [48].

In relation to recording movement, we have already seen Nadar’s fascination with sequential images in his comics, cartoons and in the Panthéon itself. This took a further step in 1864, when he visited the scientific laboratory which Étienne-Jean Marey had recently set up in Paris to measure and then analyse the movements of amphibians, birds and insects. After this visit, Nadar began experimenting with moving pictures, taking a revolving self-portrait by photographing himself a dozen times as his chair was slowly rotated through 360 degrees [49].

Nadar’s speculations as to the possibility of recording sound go back as far as 1856. In an article in Musee Francais-Anglais, he imagined a new machine called a “phonograph”, which would be an “acoustic daguerreotype, which faithfully and tirelessly reproduces all the sounds subjected to its objectivity… a box in which melodies could be caught and fixed, as the camera obscura captures ad fixes images” [48].

In relation to recording movement, we have already seen Nadar’s fascination with sequential images in his comics, cartoons and in the Panthéon itself. This took a further step in 1864, when he visited the scientific laboratory which Étienne-Jean Marey had recently set up in Paris to measure and then analyse the movements of amphibians, birds and insects. After this visit, Nadar began experimenting with moving pictures, taking a revolving self-portrait by photographing himself a dozen times as his chair was slowly rotated through 360 degrees [49].

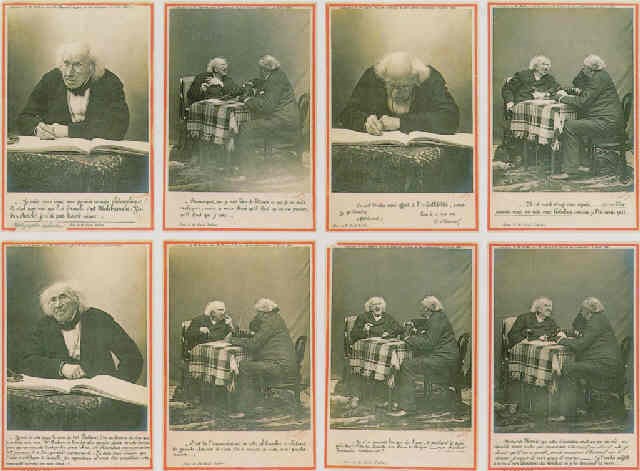

Nadar also experimented with media crossovers, with an extraordinary interview which he conducted to celebrate the scientist Michel Chevreul’s 100th birthday. During the interview, they discussed topics such as colour theory, photography, ballooning, scientific method, and the secret of a long life. Nadar then matched images of the interview (taken by his son Paul) with quotes of what Chevreul had said, then presented it as sort of Photographic Essay” in a magazine format. Viewed as whole, this early form of photo journalism bears a resemblance to a frame-by-frame presentation of a slow motion movie film.

Conclusion

Nadar was impressive on a number of fronts. Firstly, for his capacity to combine or facilitate new technical concepts that simply would not have occurred to many others – the combining of photography with ballooning to create aerial photography; the concept of photography in the dark; the combining of ballooning and a postal service to create airmail; the idea of a machine analogous to a camera that could capture sound rather than light.

Secondly, Nadar is notable for the expertise that he brought to each of his endeavours, culminating in his ballooning and photographic skills that brought him national renown. Thirdly, for the vision that enabled him to generate new ideas, the enthusiasm which inspired him to attempt to put those ideas into practice, and for the scientific knowhow that usually enabled him to do it. And finally, for the marketing chutzpah which made him one of the “earliest masters of the new art of visual publicity”[50], and which enabled him to seize the public’s attention for his latest “impossible” project.

Nadar died over a hundred years ago, in 1910. Today, an annual prize is awarded for an outstanding book on photography published in France. Fittingly, it’s called the Prix Nadar.

© Philip McCouat 2016

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “The adventures of Nadar: photography, ballooning, invention and the impressionists”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. If you enjoyed it, you may also enjoy these:

Other articles on photography: Other articles on flight: Return to Home

Secondly, Nadar is notable for the expertise that he brought to each of his endeavours, culminating in his ballooning and photographic skills that brought him national renown. Thirdly, for the vision that enabled him to generate new ideas, the enthusiasm which inspired him to attempt to put those ideas into practice, and for the scientific knowhow that usually enabled him to do it. And finally, for the marketing chutzpah which made him one of the “earliest masters of the new art of visual publicity”[50], and which enabled him to seize the public’s attention for his latest “impossible” project.

Nadar died over a hundred years ago, in 1910. Today, an annual prize is awarded for an outstanding book on photography published in France. Fittingly, it’s called the Prix Nadar.

© Philip McCouat 2016

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “The adventures of Nadar: photography, ballooning, invention and the impressionists”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. If you enjoyed it, you may also enjoy these:

Other articles on photography: Other articles on flight: Return to Home

end notes

[1] Newspaper publisher Alphonse Karr, quoted in Richard Holmes, Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, Penguin, London 1985 at 203; Helmut Gernsheim, Creative Photography: Aesthetic Trends, 1839-1960, Dover Publications Inc, New York, 1991 at 64.

[2} Holmes (Footsteps), op cit at 209.

[3] Félix Nadar, When I Was a Photographer (Transl E Cadava, L Theodoratou), The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass 2015, at 62.

[4] Philippe Willems, “Between Panoramic and Sequential: Nadar and the Serial Image”, Nineteenth-Century Worldwide, accessed May 2016 http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn12/willems-nadar-and-the-serial-image See also entry for Félix Nadar in Lambiek Comiclopedia at https://www.lambiek.net/artists/n/nadar.htm

[5] Holmes (Footsteps), op cit at 203.

[6] Nadar, op cit at 174.

[7] Nadar, op cit at 176.

[8] Holmes (Footsteps), op cit at 204.

[9] Ross King, The Judgement of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade That Gave the World Impressionism, Pimlico, London, 2007, at 106.

[10] Nadar, op cit at xix.

[11] Holmes (Footsteps), op cit at 204.

[12] Philippe Willems, op cit.

[13] Holmes (Footsteps), op cit at 204.

[14] Nadar, op cit at 57-9.

[15] Nadar, op cit at 59.

[16] Richard Holmes, Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air, William Collins, London, 2013 at 158ff.

[17] Nadar, op cit at 64-7.

[18] Nadar, op cit at 67. As with most of his inventions, Nadar was quick to file a patent for the new technology, one of dozens that he would file over his career.

[18A] The oldest surviving aerial photograph was an 1860 image taken by JW Black from 2000 feet above Boston http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/this-picture-of-boston-circa-1860-is-the-worlds-oldest-surviving-aerial-photo-14756301/

[19] Nadar, op cit at 29-30.

[20] Nadar, op cit at 31.

[21] He would later promote this in his book Le Droit au Vol (The Right to Flight).

[22] King, op cit at 110ff.

[23] Nadar, op cit at 32.

[24] Holmes (Upwards) at 164.

[25] King, op cit at 110.

[26] Nadar, op cit at 33.

[27] Nadar, cited in Rebecca Maksel, “Flight of the Giant”, Air and Space Magazine, 4 October 2013 [accessed at http://www.airspacemag.com/daily-planet/flight-of-the-giant-586517/?no-ist

[28] It appears that crowd control barriers are still known in both Belgian Dutch and Belgian French as “Nadar barriers”.

[29] Mémoires du Géant (1864).

[30] Holmes (Upwards), op cit at 179.

[31] Roger Cicala, “The Heights and Depths of Nadar”, lensrentals.com blog

http://www.lensrentals.com/blog/2014/03/the-heights-and-depths-of-nadar-tldr-version/

[32] Nadar, op cit at 75.

[33] Cicala, op cit.

[34] Nadar, op cit at 93.

[35] The whole episode of the Paris siege is memorably described in Holmes (Upwards), op cit at 251ff; see also Cicala, op cit.

[36] A similar proposal had also been made by the balloonist Eugène Godard.

[37] Some balloons also carried passengers in addition to the cargo of mail, most notably Léon Gambetta, the Minister for War in the new government.

[38] Holmes (Upwards), op cit at 259, 273.

[39] No balloon ever succeeded in flying back into Paris: Holmes (Upwards), op cit at 294.

[40] Nadar, op cit at 135-6.

[41] Nadar, op cit at 138.

[42] Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists, Chatto & Windus, London, 2006, at 117ff.

[43] Holmes (Falling Upwards) at 295.

[44] Helmut Gernsheim, Creative Photography: Aesthetic Trends, 1839-1960, Dover Publications Inc, New York, 1991, at 64.

[45] Contrary to many reports, it was not called the First impressionist Exhibition.

[46] Roe, op cit at 126.

[47] King, op cit at 356.

[48] Asa Briggs and Peter Burke, A Social History of the Media: From Gutenberg to the Internet, Polity, 2009, at 157.

[49] King, op cit at 250.

[50] Holmes (Upwards) at 157.

© Philip McCouat 2016

Return to Home

[2} Holmes (Footsteps), op cit at 209.

[3] Félix Nadar, When I Was a Photographer (Transl E Cadava, L Theodoratou), The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass 2015, at 62.

[4] Philippe Willems, “Between Panoramic and Sequential: Nadar and the Serial Image”, Nineteenth-Century Worldwide, accessed May 2016 http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn12/willems-nadar-and-the-serial-image See also entry for Félix Nadar in Lambiek Comiclopedia at https://www.lambiek.net/artists/n/nadar.htm

[5] Holmes (Footsteps), op cit at 203.

[6] Nadar, op cit at 174.

[7] Nadar, op cit at 176.

[8] Holmes (Footsteps), op cit at 204.

[9] Ross King, The Judgement of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade That Gave the World Impressionism, Pimlico, London, 2007, at 106.

[10] Nadar, op cit at xix.

[11] Holmes (Footsteps), op cit at 204.

[12] Philippe Willems, op cit.

[13] Holmes (Footsteps), op cit at 204.

[14] Nadar, op cit at 57-9.

[15] Nadar, op cit at 59.

[16] Richard Holmes, Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air, William Collins, London, 2013 at 158ff.

[17] Nadar, op cit at 64-7.

[18] Nadar, op cit at 67. As with most of his inventions, Nadar was quick to file a patent for the new technology, one of dozens that he would file over his career.

[18A] The oldest surviving aerial photograph was an 1860 image taken by JW Black from 2000 feet above Boston http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/this-picture-of-boston-circa-1860-is-the-worlds-oldest-surviving-aerial-photo-14756301/

[19] Nadar, op cit at 29-30.

[20] Nadar, op cit at 31.

[21] He would later promote this in his book Le Droit au Vol (The Right to Flight).

[22] King, op cit at 110ff.

[23] Nadar, op cit at 32.

[24] Holmes (Upwards) at 164.

[25] King, op cit at 110.

[26] Nadar, op cit at 33.

[27] Nadar, cited in Rebecca Maksel, “Flight of the Giant”, Air and Space Magazine, 4 October 2013 [accessed at http://www.airspacemag.com/daily-planet/flight-of-the-giant-586517/?no-ist

[28] It appears that crowd control barriers are still known in both Belgian Dutch and Belgian French as “Nadar barriers”.

[29] Mémoires du Géant (1864).

[30] Holmes (Upwards), op cit at 179.

[31] Roger Cicala, “The Heights and Depths of Nadar”, lensrentals.com blog

http://www.lensrentals.com/blog/2014/03/the-heights-and-depths-of-nadar-tldr-version/

[32] Nadar, op cit at 75.

[33] Cicala, op cit.

[34] Nadar, op cit at 93.

[35] The whole episode of the Paris siege is memorably described in Holmes (Upwards), op cit at 251ff; see also Cicala, op cit.

[36] A similar proposal had also been made by the balloonist Eugène Godard.

[37] Some balloons also carried passengers in addition to the cargo of mail, most notably Léon Gambetta, the Minister for War in the new government.

[38] Holmes (Upwards), op cit at 259, 273.

[39] No balloon ever succeeded in flying back into Paris: Holmes (Upwards), op cit at 294.

[40] Nadar, op cit at 135-6.

[41] Nadar, op cit at 138.

[42] Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists, Chatto & Windus, London, 2006, at 117ff.

[43] Holmes (Falling Upwards) at 295.

[44] Helmut Gernsheim, Creative Photography: Aesthetic Trends, 1839-1960, Dover Publications Inc, New York, 1991, at 64.

[45] Contrary to many reports, it was not called the First impressionist Exhibition.

[46] Roe, op cit at 126.

[47] King, op cit at 356.

[48] Asa Briggs and Peter Burke, A Social History of the Media: From Gutenberg to the Internet, Polity, 2009, at 157.

[49] King, op cit at 250.

[50] Holmes (Upwards) at 157.

© Philip McCouat 2016

Return to Home