Millet and the Angelus

How a painting of potato farmers became the most expensive modern painting in the world

By Philip McCouat For readers' comments on this article see here

INtroduction

The nineteenth century painting The Angelus, by Jean-François Millet, is known throughout the world, and is one of the most famous paintings in its native France. Reproductions of it hang on the walls of tens of thousands of French homes, schools and churches, and appear on items as varied as postcards and coffee cups. Yet, on its face, it just looks like an attractive, rural painting. It’s set on a vast open field, with a brilliant sunset sky, while a working man and woman stand quietly in the foreground, their faces obscured, heads bowed, a basket of potatoes at their feet. A glance at the title – The Angelus -- tells us that they are performing their daily prayer.

So, what is there about this work that could lead to its becoming the most expensive modern painting in the world? To a patriotic fervour, to an attack by a stabbing madman, to an obsession that overwhelmed Salvador Dali, to the possible discovery of a dead baby, and to the introduction of a revolutionary new way of rewarding artists?

In this article we look for the answers in this extraordinary story.

So, what is there about this work that could lead to its becoming the most expensive modern painting in the world? To a patriotic fervour, to an attack by a stabbing madman, to an obsession that overwhelmed Salvador Dali, to the possible discovery of a dead baby, and to the introduction of a revolutionary new way of rewarding artists?

In this article we look for the answers in this extraordinary story.

Origin of the Angelus

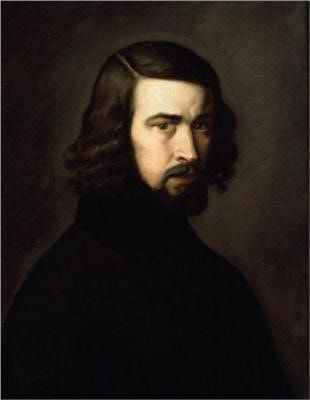

Millet was a member of the Barbizon school of painters. The Barbizons emerged in the 1830s; they rejected Society painting and turned instead to nature for their inspiration, replacing artifice with more realistic representations, using a looser, less-finished style of brushwork and softer, less sharply-defined forms. Millet later attempted to extend this to include depictions of the peasants who worked outdoors in natural surroundings. However, this met considerable resistance, and the late 1850s proved to be a lean time for him. He struggled to sell his characteristic painting The Gleaners (Fig 2); its depiction of poor rural women collecting stray bits of crops led many conservative critics to brand it as working class, ugly, and gross, with even its large size being criticised as being too big for such an inappropriately menial subject. Millet finally had to accept a substantially discounted offer for the work, prompting him to say to his agent Alfred Sensier, "I would prefer that the price given to me for my painting not be revealed… Would it be too dishonest to pretend that it sold for 4,000?"[1].

Millet’s next painting, again dealing with peasant life, Prayer for the Potato Crop, also hit a snag. It was originally commissioned by Thomas Gold Appleton, a wealthy Bostonian of Irish descent, possibly inspired by memories of the recent disastrous Irish potato famine. As it happened, however, the deal fell through. Appleton ultimately declined to accept the painting, leading a rather desperate Millet to modify it in the hope of making it more generally saleable. He added a church tower in the distance and changed the name of the painting to The Angelus, the daily prayer common in Catholic countries [2]. Millet would later say, "The idea for The Angelus came to me because I remembered that my grandmother, hearing the church bell ringing while we were working in the fields, always made us stop work to say the Angelus prayer for the poor departed, very religiously and with cap in hand".

This seemingly simple change to the painting at least helped him to sell it, though only for a very low 1,000 francs [3]. However, ultimately, it would prove to be a masterstroke, with implications that Millet could never have dreamed of. Within 30 years, and well after his death, Millet would become posthumously famous throughout the world, and the painting would fetch a fortune at auction -- in fact, the highest price ever for a modern painting to that date. How could this vast explosion in value be explained?

Factors increasing its prestige and value

The reasons for this dramatic change in the painting’s fortunes were a combination of deep national sentiment, of changing tastes in art, and of the hard-edged operation of the market.

#1 Importance of the Angelus prayer in French life

The Angelus prayer, the subject of Millet’s re-titled painting, had a peculiarly significant role in 19th century French life [4]. The prayer gets its name from the fact that it commemorates the Angel Gabriel’s communication to Mary that she would conceive and become the mother of Jesus, the Son of God. Traditionally, the Angelus was signalled by the ringing of a church bell, and was said three times daily, at dawn, noon and evening, corresponding to the start, the lunch break, and the close of the working day.

The sounding of the bell that signalled the time for the prayer was particularly significant. Graham Robb has written how in traditional French rural societies, “At certain times of the day, even if the boundaries are invisible, the approximate limits of a pays [micro-province] can be detected…. The area in which a church bell can be heard more distinctly than those of other villages in the region is likely to be an area whose inhabitants had the same customs and language, the same memories and fears, and the same local saint… Hardly anyone complained about excessive ringing, but there were countless complaints about bells that were too faint to be heard in the outlying fields” [5].

This significance was tangible in people’s perceptions of the painting. When Millet’s agent Alfred Sensier first saw the painting, Millet asked him: “Well, what do you think of it?” “It’s the Angelus,” acknowledged Sensier. To which Millet replied: “Can you hear the bells?” Much later, when the then-current owner of the painting, Belgian diplomat Jules van Praet, commented, “What can I say? It is clearly a masterpiece, but faced with these two peasants, whose work is interrupted by prayer, everyone thinks they can hear the nearby church bell tolling” [6]. Clearly, Millet’s simple insertion of the church tower in the background was proving to be important.

The sounding of the bell that signalled the time for the prayer was particularly significant. Graham Robb has written how in traditional French rural societies, “At certain times of the day, even if the boundaries are invisible, the approximate limits of a pays [micro-province] can be detected…. The area in which a church bell can be heard more distinctly than those of other villages in the region is likely to be an area whose inhabitants had the same customs and language, the same memories and fears, and the same local saint… Hardly anyone complained about excessive ringing, but there were countless complaints about bells that were too faint to be heard in the outlying fields” [5].

This significance was tangible in people’s perceptions of the painting. When Millet’s agent Alfred Sensier first saw the painting, Millet asked him: “Well, what do you think of it?” “It’s the Angelus,” acknowledged Sensier. To which Millet replied: “Can you hear the bells?” Much later, when the then-current owner of the painting, Belgian diplomat Jules van Praet, commented, “What can I say? It is clearly a masterpiece, but faced with these two peasants, whose work is interrupted by prayer, everyone thinks they can hear the nearby church bell tolling” [6]. Clearly, Millet’s simple insertion of the church tower in the background was proving to be important.

So, for a highly religious community such as rural nineteenth-century France – where three-quarters of the population worked in rural agriculture, including Millet himself in his youth -- the Angelus was not only a prayer, but a potent reminder of the structure of their daily working life, and of the life of their community. Any painting that could capture this feeling, as Millet’s revamped Angelus now did, had the potential for success.

#2 Growing appeal to wider market

Millet’s reputation, solid during his lifetime, only became stellar after his death in 1875. Two posthumous auctions of his work and an exhibition of his drawings had enabled a more comprehensive understanding of his body of work [7]. His reputation was given a further boost by the after-effects of the twin disasters of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, which had led many people in France to desperately look for unifying, stable national symbols. Many conservatives and religious people felt anxious to return to old familiar, traditional ways. For them, paintings such as Millet’s Angelus could now be seen as highly attractive. Even though the people in the painting were ”just” lowly peasants, they were clearly and overtly devout, honest toilers solemnly affirming traditional French values by performing their prayer. This aspect gradually overcame any lingering feeling that any depiction of peasants was in some way suggestive of socialist leanings -- the peasants in The Angelus were clearly not radicals, or even oppressed; in contrast they simply appeared to be worthy and hard-working.

At the other end of the spectrum, the painting also came to appeal to those with more liberal views, who actually welcomed the fact that working class peasantry were being portrayed, in contrast to the middle-to-upper class subject-matter and stuffiness of much previous “respectable” art. Despite its religious associations, the painting’s outdoor subject matter, its sympathetic but realistic representation of manual workers, its use of non-professional models. its softness of form, and its looser brushwork -- contrasting with the highly finished artworks that previously had been so highly valued by the Establishment -- also began to be influential in artistic circles, including the Impressionists, contributing to its increasing reputation [8].

For both sides, conservatives and liberals alike, the painting also had the virtue of appearing undeniably and quintessentially French. So, for all these varying reasons, The Angelus gradually started to assume a substantially higher position in the popular consciousness.

At the other end of the spectrum, the painting also came to appeal to those with more liberal views, who actually welcomed the fact that working class peasantry were being portrayed, in contrast to the middle-to-upper class subject-matter and stuffiness of much previous “respectable” art. Despite its religious associations, the painting’s outdoor subject matter, its sympathetic but realistic representation of manual workers, its use of non-professional models. its softness of form, and its looser brushwork -- contrasting with the highly finished artworks that previously had been so highly valued by the Establishment -- also began to be influential in artistic circles, including the Impressionists, contributing to its increasing reputation [8].

For both sides, conservatives and liberals alike, the painting also had the virtue of appearing undeniably and quintessentially French. So, for all these varying reasons, The Angelus gradually started to assume a substantially higher position in the popular consciousness.

#3 Promotion by vigorous champions

A further factor in the rise of Millet, and in particular his Angelus, was the active promotion that the painting received from Millet’s agent Alfred Sensier, who had cannily noted the progressive increases in its value that were occurring as it changed hands a number of times during the 1870s. In 1881, his flattering but influential biography of Millet was published [9], in which the Angelus featured prominently, with the author characterising it as an icon of French nostalgia, a pious idyll and a symbol of spiritual renewal [10].

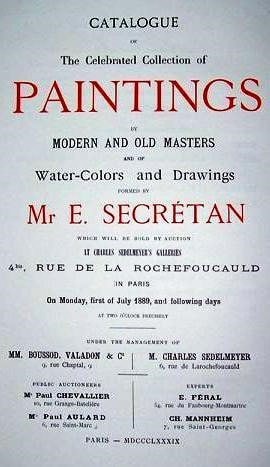

In the same year in which Sensier’s biography appeared, the Belgian collector JW Wilson sold the Angelus at auction to the French copper magnate Pierre-Eugène Secrétan for 168,000 francs. This was more than four times the amount Wilson had paid for it a few years earlier, and the auction catalogue was now describing it as “perhaps Millet’s masterpiece… The Angelus is solemn like a prayer”. It probably helped that the author of the catalogue, the well-respected and credentialled Paul Mantz, was a long-time Millet defender and promoter of the view that Millet had managed to achieve a powerful marriage of modernity and tradition, of the simple and the universal, of the religious and the secular. By 1887, when the Ecole des Beaux-Arts staged a retrospective exhibition of Millet’s work, even conservative critics were giving it a warm reception, with special praise for the Gleaners and the Angelus, describing the latter as “truly touching the sublime” or “an admirable masterpiece of religious poetry”[11].

#4 Fear of loss at a critical time

In 1889, Secrétan lost a fortune after the failure of an attempt to corner the market on copper, and resolved to cover his losses by selling off his large art collection, including the Angelus as its centrepiece. Fortuitously, this was also the year in which France was to hold its Exposition Universelle, the centennial of the French Revolution. This showcased France’s engineering wonders, such as the newly-constructed Eiffel Tower, and other achievements, with special emphasis being given to the country’s rich artistic heritage. Paul Mantz was the honorary director of this aspect, and in his official guide to the history of French art, named Millet as the greatest French artist of the past century.

Secrétan resolved to maximise publicity for the auction by timing it to coincide with the expected huge influx of overseas visitors to the Exposition, hoping to exploit United States interest, and arranged for his catalogue printed in both French and English. The auction therefore took place, not only in the climate of extreme nationalism of the Exposition, but also at the height of both Millet’s and the Angelus’ popularity. French indignation had also been stirred by the fact that foreigners, particularly in the United States, had already bought some of Millet’s other works, and the need to preserve The Angelus in French hands was seen as an issue of national importance [12]. The intensity of the situation was well captured by a journalist for L`Art Moderne in these words;

‘On that day, the auction hall was packed with a crowd on which the breath of the nation passed. There were among us some who had insulted Millet in past times, when his paintings sold for one hundred francs. They were the most ardent enthusiasts. The collectors were stomping their feet with impatience. Among them, one, twenty years ago, had not agreed to pay ten francs for this patriotic masterpiece. And Millet belonged to them, to all of the people there. Millet was their patrimony. They were supremely angered to think that the painter had suffered misery and contempt. One, above all, made himself noticed by his agitation. He went to M. Antonin Proust [head of a private consortium formed to bid for the painting to keep it in France], very emotional . . . saying in a trembling voice: "You are France, Millet is France, we are all France: a million [francs] if need be. France-you, Millet and I-we cannot sustain the disgrace of defeat!"’ [13].

After a spirited bidding war, the painting was sold for a record 553,000 francs to the pro-French Proust consortium, but it later turned out that this was conditional on the French government reimbursing it for the vast purchase price. This, however, did not eventuate, and the painting passed instead to the under-bidder, the American Art Association, only to return – finally -- to France when French department store tycoon Alfred Chauchard repurchased it for an eye-watering 750,000 / 800,000 francs and later bequested it to the Louvre [14]. The whole episode also incidentally served to highlight the Louvre’s limited ability or capacity to successfully bid for desirable art in the modern marketplace, and prompted the formation of a fund designed to acquire works of art to enrich the national collections [15].

This however was not the end of the story. As we shall see, the Angelus had a surprising and continuing capacity to affect artist’s lives and thoughts, and even their livelihoods.

‘On that day, the auction hall was packed with a crowd on which the breath of the nation passed. There were among us some who had insulted Millet in past times, when his paintings sold for one hundred francs. They were the most ardent enthusiasts. The collectors were stomping their feet with impatience. Among them, one, twenty years ago, had not agreed to pay ten francs for this patriotic masterpiece. And Millet belonged to them, to all of the people there. Millet was their patrimony. They were supremely angered to think that the painter had suffered misery and contempt. One, above all, made himself noticed by his agitation. He went to M. Antonin Proust [head of a private consortium formed to bid for the painting to keep it in France], very emotional . . . saying in a trembling voice: "You are France, Millet is France, we are all France: a million [francs] if need be. France-you, Millet and I-we cannot sustain the disgrace of defeat!"’ [13].

After a spirited bidding war, the painting was sold for a record 553,000 francs to the pro-French Proust consortium, but it later turned out that this was conditional on the French government reimbursing it for the vast purchase price. This, however, did not eventuate, and the painting passed instead to the under-bidder, the American Art Association, only to return – finally -- to France when French department store tycoon Alfred Chauchard repurchased it for an eye-watering 750,000 / 800,000 francs and later bequested it to the Louvre [14]. The whole episode also incidentally served to highlight the Louvre’s limited ability or capacity to successfully bid for desirable art in the modern marketplace, and prompted the formation of a fund designed to acquire works of art to enrich the national collections [15].

This however was not the end of the story. As we shall see, the Angelus had a surprising and continuing capacity to affect artist’s lives and thoughts, and even their livelihoods.

A revered inspiration for Van Gogh…

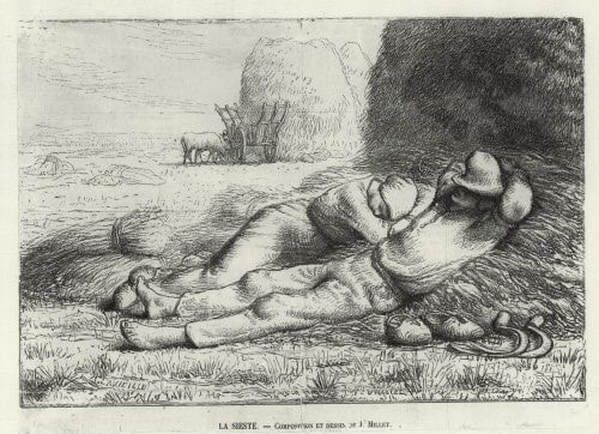

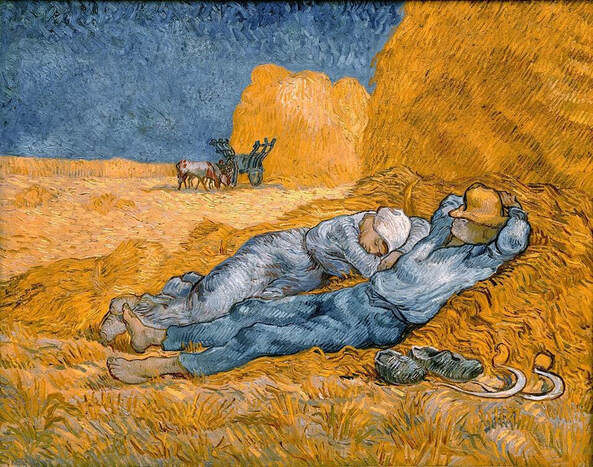

Millet and his works, both paintings and drawings, proved to be influential on many other artists, including Winslow Homer, Seurat, Degas and Monet [16]. Indeed, Cezanne described Millet as an artist who had started a “revolution” by “rediscovering nature” [17].

But by far the most far-reaching artistic impact was on Vincent van Gogh, for whom Millet became the leading inspiration. Vincent identified strongly with Millet, as a simple man who grew up in a peasant family, had respect for peasant life and was proud of his roots. He devoured Sensier’s 1881 biography on Millet -- which he said “interests me so much that it wakes me up in the night”-- and In his letters to his brother Leo throughout the 1880s, Vincent would constantly refer to Millet in glowing terms, such as, "Millet is Father Millet, counsellor and mentor in everything for young artists".

Referring specifically to the Angelus, Vincent wrote, “that‘s it, that’s rich, that’s poetry”. He commented admiringly that in Millet’s Sower, “the peasant appears to be painted with the earth that he is sowing”; scorned the “art dealers and experts” who initially rejected Millet; and described him as “the great Master, as leader… the very heart of modern art” and the “ essential modern painter who opened the horizon to many”. For Van Gogh, it was impossible to surpass Millet and his fellow Barbizon painter Jules Breton -- “their genius may be equalled, but to surpass it is not possible … Certainly we shall still see beautiful things in the years to come, but [nothing] more sublime than we have seen already” [18].

Van Gogh began copying Millet’s works (including the Angelus) back in 1880, when he was still learning his craft, and under Millet’s influence, his focus was firmly on painting peasant life. Later, after Vincent’s move to Paris broadened and brightened his palette, Vincent would continue to draw inspiration from Millet, though this time with the stamp of himself as mature artist. Later still, toward the end of his life when he was ill in an asylum, he obsessively painted no fewer than 21 copies (“translations in colour”) of Millet’s work in a three-month period.

But by far the most far-reaching artistic impact was on Vincent van Gogh, for whom Millet became the leading inspiration. Vincent identified strongly with Millet, as a simple man who grew up in a peasant family, had respect for peasant life and was proud of his roots. He devoured Sensier’s 1881 biography on Millet -- which he said “interests me so much that it wakes me up in the night”-- and In his letters to his brother Leo throughout the 1880s, Vincent would constantly refer to Millet in glowing terms, such as, "Millet is Father Millet, counsellor and mentor in everything for young artists".

Referring specifically to the Angelus, Vincent wrote, “that‘s it, that’s rich, that’s poetry”. He commented admiringly that in Millet’s Sower, “the peasant appears to be painted with the earth that he is sowing”; scorned the “art dealers and experts” who initially rejected Millet; and described him as “the great Master, as leader… the very heart of modern art” and the “ essential modern painter who opened the horizon to many”. For Van Gogh, it was impossible to surpass Millet and his fellow Barbizon painter Jules Breton -- “their genius may be equalled, but to surpass it is not possible … Certainly we shall still see beautiful things in the years to come, but [nothing] more sublime than we have seen already” [18].

Van Gogh began copying Millet’s works (including the Angelus) back in 1880, when he was still learning his craft, and under Millet’s influence, his focus was firmly on painting peasant life. Later, after Vincent’s move to Paris broadened and brightened his palette, Vincent would continue to draw inspiration from Millet, though this time with the stamp of himself as mature artist. Later still, toward the end of his life when he was ill in an asylum, he obsessively painted no fewer than 21 copies (“translations in colour”) of Millet’s work in a three-month period.

…. a “dead baby” obsession for Dali

Somewhat bizarrely, Millet’s Angelus also become an extraordinary long-term obsession for the 20th century surrealist artist Salvador Dali. He had apparently first seen a print of it hanging on his schoolroom wall, and said that many years later, “it suddenly appeared in my mind… It left with a profound impression. I was most upset by it… [It] suddenly became for me the most troubling of pictorial works, the most enigmatic, the most dense, the richest in unconscious thoughts that had ever existed” [19].

Dali set about collecting Angelus cartoons and postcards from all over the world [20]. With the Angelus now haunting his thoughts and visions, Dali made numerous imaginative paintings based on or inspired by it (Fig 8). In 1938 also published a book, The Tragic Story of the Angelus of Millet, in which he gave it a “paranoiac-critical” Interpretation, arguing that the painting was a cultural icon that hid feelings of anguish and sexual repression, and argued that the couple were actually grieving over the death of a stillborn baby, not a basket of potatoes. When X-rays later became available for investigating paintings, he started lobbying vigorously for this to be done with the Angelus.

Dali set about collecting Angelus cartoons and postcards from all over the world [20]. With the Angelus now haunting his thoughts and visions, Dali made numerous imaginative paintings based on or inspired by it (Fig 8). In 1938 also published a book, The Tragic Story of the Angelus of Millet, in which he gave it a “paranoiac-critical” Interpretation, arguing that the painting was a cultural icon that hid feelings of anguish and sexual repression, and argued that the couple were actually grieving over the death of a stillborn baby, not a basket of potatoes. When X-rays later became available for investigating paintings, he started lobbying vigorously for this to be done with the Angelus.

Eventually, in the 1960s, this actually occurred, with the painting being scanned at the Louvre Museum. Surprisingly, the scan revealed that that the basket of potatoes that now appears in the painting was originally a more box-like object. With a major dose of imagination, this could be interpreted by some as a baby’s coffin, and certainly Dali treated it as a triumphant vindication, promptly re-publishing his book in an updated form [21].

… and inspiring new rules for rewarding artists

Like all artists at the time, Millet received no continuing financial benefit from any subsequent resales of his paintings after their original sale. In the years after his death in 1875, it seems that his large family fell into some financial difficulties, culminating with the reported destitution of his granddaughter who, it was said, had been reduced to selling flowers in the streets of Paris [22]. When the staggering price received by Secrétan on the sale of The Angelus in 1889 highlighted this anomalous situation, it created somewhat of a public stir. This in turn played an important role in a long and drawn-out campaign to establish a system of royalties that would be payable to artists on subsequent resale of the works that they had created [23].

Fig 9: Drawing by Jean-Louis Forain, which appeared on the front page of a Paris newspaper in 1920, supporting the introduction of the royalty scheme. Referring to the Millet situation, it depicts wealthy, fat businessmen crowded round a framed canvas which is for auction, while an impoverished beggar and child look on, exclaiming “one of papa’s paintings!”

The royalty scheme was promoted as a welfare measure, as in the case of Millet’s family, but also on the basis of the wider principle that artists and their heirs should have something similar to the copyright protection that authors enjoyed with their literary creations. After some years of debate and controversy, this new system of royalties, known as “droit de suite” (meaning “right to follow”) eventually came into effect in France in 1920.

Despite vigorous lobbying by vested interests, similar systems, usually described as artist resale royalty regimes, have been progressively instituted in over 70 countries including the European Union, the United Kingdom and Australia. For further discussion on artists’ royalties, see our article at [24].

Despite vigorous lobbying by vested interests, similar systems, usually described as artist resale royalty regimes, have been progressively instituted in over 70 countries including the European Union, the United Kingdom and Australia. For further discussion on artists’ royalties, see our article at [24].

Conclusion

Some paintings just seem to attract strong passions. As we have seen, The Angelus has at various times attracted an intense national fervour, become a total obsession for Salvador Dali, and helped inspire a controversial, revolutionary new method of rewarding artists for their creations. In conjunction with Millet’s other works, it has also inspired an intensely devoted and almost devotional response by Vincent van Gogh. Given this provocative record, it is perhaps not totally surprising to learn that on, 11 August 1932, it attracted the attention of one Pierre Guillard, a crazed 31-year-old engineer, who entered the Louvre, located The Angelus, and slashed it several times with a jack-knife [25]. Guards overpowered him before the painting was ruined, with the damage being significant but repairable. Asked why he did it, he is said to have replied, “At least they will talk about me”. Guillard certainly received his 15 minutes of fame, but The Angelus has lived on.

Since those heady times, however, Millet’s international reputation has waned, especially in the latter part of the 20th century, along with a general reaction against the perceived sentimentality of much 19th century art, the decline of interest in religious themes, and the rise in radically different trends in contemporary art. However, in more recent times, there are signs that a revival of interest in Millet may be occurring, with a greater appreciation of his role in freeing art from the shackles of what was previously seen as “respectable” art, and his deep influence on other artists. This culminated in a major exhibition of Millet and his influences scheduled for 2020 [26]. In the light of its extraordinary past, who can be sure of what else may be in store? ■

First published August 2020; © Philip McCouat, 2020

You are welcome to comment on this article. If you enjoyed it, you may also be interested in these others:

RETURN TO HOME

Since those heady times, however, Millet’s international reputation has waned, especially in the latter part of the 20th century, along with a general reaction against the perceived sentimentality of much 19th century art, the decline of interest in religious themes, and the rise in radically different trends in contemporary art. However, in more recent times, there are signs that a revival of interest in Millet may be occurring, with a greater appreciation of his role in freeing art from the shackles of what was previously seen as “respectable” art, and his deep influence on other artists. This culminated in a major exhibition of Millet and his influences scheduled for 2020 [26]. In the light of its extraordinary past, who can be sure of what else may be in store? ■

First published August 2020; © Philip McCouat, 2020

You are welcome to comment on this article. If you enjoyed it, you may also be interested in these others:

- The shocking birth and amazing career of Guernica

- Lost in Translation: Bruegel’s Tower of Babel

- Carpaccio’s Double Enigma: Hunting on the Lagoon and The Two Venetian Ladies

RETURN TO HOME

end notes

[1] Bradley Fratello, “France Embraces Millet: The Intertwined Fates of The Gleaners and The Angelus”, The Art Bulletin, December 2003 https://www.mutualart.com/Article/France-Embraces-Millet--The-Intertwined-/65DB908A334354D8

[2] Gil Baillie, “Bells and Whistles: The Technology of Forgetfulness”, Fellowship of Catholic Scholars Quarterly, Vol. 41, No. 3 Fall 2018 at 287 ff

[3] Fratello, op cit. The purchaser was Belgian landscape painter Victor de Papeleu

[4] Fratello, op cit

[5] Graham Robb, The Discovery of France, Picador, London 2007 at 30, 31

[6] Emphasis added. Van Praet also quipped, “…In the end, the constant ringing just became tiresome”

[7] Fratello, op cit

[8] For specific influences on painters such as Van Gogh, see further under the heading “A revered inspiration for Van Gogh”

[9] La Vie et Oeuvre de J.-F. Millet. Sensier died before publication

[10] Fratello, op cit

[11] Fratello, op cit

[12] Fratello, op cit

[13] Quoted in Fratello, op cit

[14] Since 1986, the painting has been at the Musée d’Orsay

[15] Fratello, op cit

[16] This approval was not universal. In 1887 Camille Pissarro described the Angelus as one of the painter’s poorest works and denigrated its religious sentimentality: Fratello, op cit

[17] St Louis Art Museum, online exhibition essay Millet and Modern Art; From Van Gogh to Dali https://www.slam.org/explore-the-collection/millet-and-modern-art/

[18] Vincent van Gogh, The Letters: http://vangoghletters.org/vg/

[19] James Elkins, “What is Interesting Writing in Art History?” Ch 16 http://305737.blogspot.com/2013/03/chapter-16.html

[20] Salvador Dali, The Tragic Story of the Angelus of Millet (1938)

[21] Whitney Chadwick, Myths in Surrealist Painting 1929-39, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press 1980, at 65; see also Claire Nouvet "Searching for a Grave in Millet's Angelus: The 'Death Zone' of Salvador Dali", Psychoanalysis in French and Francophone Literature and Film, Vol XXXVIII, 2011

[22] It is possible that the severity of this situation was overstated at the time, for dramatic effect

[23] Though its impact was important, there were other factors that also played a role in the campaign, such as the desire to assist widows whose artist-husbands had been killed in World War I, and the apparent success of a scheme devised by a private syndicate of art investors, who paid artists a share of the sale proceeds of their paintings: P. Lewis, “The resale royalty and Australian visual artists: painting the full picture” (2003) 8 Media and Arts Law Review 306, at 307; Jonathan Barrett “An analysis of Jean-François Millet’s The Angelus and the origins of droit de suite through the multifocal lens of love”, Journal of Intellectual Property Law and Practice, publ July 2020, https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpaa093

[24] Philip McCouat, “Should artists get royalties?” Journal of Art in Society, http://www.artinsociety.com/should-artists-get-royalties.html

[25] “Art: Stabbed at Prayers”, Time, August 22, 1932

[26] “Millet and Modern Art: From Van Gogh to Dali”, a major exhibition by St Louis Art Museum and the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, February 2020.

© Philip McCouat, 2020

RETURN TO HOME

[2] Gil Baillie, “Bells and Whistles: The Technology of Forgetfulness”, Fellowship of Catholic Scholars Quarterly, Vol. 41, No. 3 Fall 2018 at 287 ff

[3] Fratello, op cit. The purchaser was Belgian landscape painter Victor de Papeleu

[4] Fratello, op cit

[5] Graham Robb, The Discovery of France, Picador, London 2007 at 30, 31

[6] Emphasis added. Van Praet also quipped, “…In the end, the constant ringing just became tiresome”

[7] Fratello, op cit

[8] For specific influences on painters such as Van Gogh, see further under the heading “A revered inspiration for Van Gogh”

[9] La Vie et Oeuvre de J.-F. Millet. Sensier died before publication

[10] Fratello, op cit

[11] Fratello, op cit

[12] Fratello, op cit

[13] Quoted in Fratello, op cit

[14] Since 1986, the painting has been at the Musée d’Orsay

[15] Fratello, op cit

[16] This approval was not universal. In 1887 Camille Pissarro described the Angelus as one of the painter’s poorest works and denigrated its religious sentimentality: Fratello, op cit

[17] St Louis Art Museum, online exhibition essay Millet and Modern Art; From Van Gogh to Dali https://www.slam.org/explore-the-collection/millet-and-modern-art/

[18] Vincent van Gogh, The Letters: http://vangoghletters.org/vg/

[19] James Elkins, “What is Interesting Writing in Art History?” Ch 16 http://305737.blogspot.com/2013/03/chapter-16.html

[20] Salvador Dali, The Tragic Story of the Angelus of Millet (1938)

[21] Whitney Chadwick, Myths in Surrealist Painting 1929-39, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press 1980, at 65; see also Claire Nouvet "Searching for a Grave in Millet's Angelus: The 'Death Zone' of Salvador Dali", Psychoanalysis in French and Francophone Literature and Film, Vol XXXVIII, 2011

[22] It is possible that the severity of this situation was overstated at the time, for dramatic effect

[23] Though its impact was important, there were other factors that also played a role in the campaign, such as the desire to assist widows whose artist-husbands had been killed in World War I, and the apparent success of a scheme devised by a private syndicate of art investors, who paid artists a share of the sale proceeds of their paintings: P. Lewis, “The resale royalty and Australian visual artists: painting the full picture” (2003) 8 Media and Arts Law Review 306, at 307; Jonathan Barrett “An analysis of Jean-François Millet’s The Angelus and the origins of droit de suite through the multifocal lens of love”, Journal of Intellectual Property Law and Practice, publ July 2020, https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpaa093

[24] Philip McCouat, “Should artists get royalties?” Journal of Art in Society, http://www.artinsociety.com/should-artists-get-royalties.html

[25] “Art: Stabbed at Prayers”, Time, August 22, 1932

[26] “Millet and Modern Art: From Van Gogh to Dali”, a major exhibition by St Louis Art Museum and the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, February 2020.

© Philip McCouat, 2020

RETURN TO HOME