The shocking birth and amazing career of Guernica

|

By Philip McCouat

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, painted in 1937, is one of the most famous paintings in the world. How did it come to be painted? Why does it look as it does? And why it has achieved such extraordinary recognition? |

More on art and war

The Isenheim Altarpiece Pt 2: nationalism, nazism and degeneracy Bellotto and the reconstruction of Warsaw From the Rokeby Venus to Fascism Pt 2: the strange allure of fascism ------------------------------------------------------------------- |

The circumstances of its birth were indeed shocking. In 1936, Spain had entered a bitter civil war, after a coup attempt led by General Franco against the democratic Republican coalition government [1]. Franco’s military aims were supported by elements of the Spanish military, together with German and Italian fascist forces. His political aims were also supported by major elements in the Spanish church, industry and aristocracy. But he was bitterly opposed by many of the citizens.

In January 1937, a delegation from the increasingly-beleaguered Republican government visited Picasso at his home in Paris, and asked him to create a large painting for the Spanish Pavilion at the forthcoming World’s Fair in that city. The Pavilion was intended to be an anti-Franco propaganda exercise for the government [2]. The delegation suggested to Picasso that his participation would serve to remind the people that he was a son of Spain, and that he opposed the fascists. However, Picasso was initially lukewarm about the proposal. The projected size of the work was daunting, and he was uneasy with the idea of being commissioned to do specific work. He was also reluctant to engage in such an overt propaganda effort.

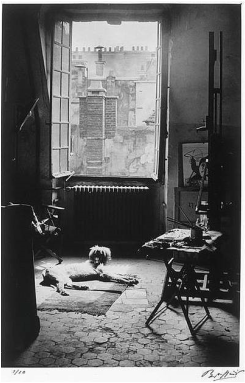

Picasso also dithered about what theme to adopt. As an interim measure, he engraved Dream and Lie of Franco, a series of small, comic book vignettes that vitriolically and obscenely parodied the “evil-omened polyp” Franco [3]. He then tentatively started sketching on the theme of “The Artist in his Studio”[4]. However, events soon dramatically intervened.

On 27 April 1937, news reports [4A] reached Paris that German Luftwaffe planes of the Condor Legion, acting with Franco’s complicity, had firebombed and almost totally destroyed the Basque town of Gernika (Fig 1)[5]. The attack, under the command of Colonel Wolfram von Richthofen [6], had a number of possible aims. One was to cut off the line of retreat for the opposing forces. Another was to demoralise remaining resistance in the Basque areas. Although the town itself had little military strategic value, the region contained major mineral, manufacturing and shipbuilding resources. Gernika was also the emotional heartland of the Basques, whom Franco despised because of their tradition of independence and “different-ness” in customs, laws and language. In addition, from the German point of view, the attack served as a useful test of their newly-devised “blitzkrieg” tactics of total war, tactics that would later be used successfully in the Second World War.

In January 1937, a delegation from the increasingly-beleaguered Republican government visited Picasso at his home in Paris, and asked him to create a large painting for the Spanish Pavilion at the forthcoming World’s Fair in that city. The Pavilion was intended to be an anti-Franco propaganda exercise for the government [2]. The delegation suggested to Picasso that his participation would serve to remind the people that he was a son of Spain, and that he opposed the fascists. However, Picasso was initially lukewarm about the proposal. The projected size of the work was daunting, and he was uneasy with the idea of being commissioned to do specific work. He was also reluctant to engage in such an overt propaganda effort.

Picasso also dithered about what theme to adopt. As an interim measure, he engraved Dream and Lie of Franco, a series of small, comic book vignettes that vitriolically and obscenely parodied the “evil-omened polyp” Franco [3]. He then tentatively started sketching on the theme of “The Artist in his Studio”[4]. However, events soon dramatically intervened.

On 27 April 1937, news reports [4A] reached Paris that German Luftwaffe planes of the Condor Legion, acting with Franco’s complicity, had firebombed and almost totally destroyed the Basque town of Gernika (Fig 1)[5]. The attack, under the command of Colonel Wolfram von Richthofen [6], had a number of possible aims. One was to cut off the line of retreat for the opposing forces. Another was to demoralise remaining resistance in the Basque areas. Although the town itself had little military strategic value, the region contained major mineral, manufacturing and shipbuilding resources. Gernika was also the emotional heartland of the Basques, whom Franco despised because of their tradition of independence and “different-ness” in customs, laws and language. In addition, from the German point of view, the attack served as a useful test of their newly-devised “blitzkrieg” tactics of total war, tactics that would later be used successfully in the Second World War.

There were hundreds of casualties, mainly women and children [7]. The ferocity and scale of the destruction, indeed the very idea of an all-out air attack on civilians, was believed to be unprecedented. On May Day, there were anti-Franco demonstrations in Paris and, on the same day, an energised Picasso started a new series of sketches that, in a few weeks of extraordinarily intense effort, would result in Guernica [8].

Guernica presents an image of dying and suffering in the chaotic aftermath of a disaster. The subject of suffering was not new for Picasso, who had long been interested in depicting the infliction of pain. Nor for that matter, was it new to Spanish art [9], or ways of thinking [10]. However, what is particularly striking is that the depicted disaster is generic. Apart from its title [11], the painting does not directly refer either to Gernika or to bombing at all – Picasso has resisted the obvious temptation to take specific imagery from the actual event [12]. Furthermore, although Picasso clearly intended that the painting would be a clear expression of his “loathing of the [Franco] military caste” [13], the painting itself contains no obvious references to heroes or villains, and does not directly appear to attribute blame [14].

picasso's artistic inspirations

What artistic inspirations did Picasso draw from in composing such a dramatic image [15]?

One external source that is commonly cited as an influence [16] is Rubens’ An Allegory Showing the Effects of War (Horrors of War) (1638) (Fig 3) This work certainly has some iconographic and compositional parallels with Guernica. A mirror image of Rubens’ work includes, from left to right, a weeping woman with a child in her arms; a flying “Fury of War” with a piece of clothing draped over her arm and holding out a torch; a upwards-facing woman with arms outstretched; and a building with an open door. All have equivalents in Guernica, and it may well be that Picasso has obtained inspiration there, particularly as he is known to have admired Rubens’s works.

Another possible source is Goya’s 3rd May, 1808 (Execution of the Defenders of Madrid, 3rd May, 1808). Like Guernica, this depicts a Spanish wartime massacre at night [17], with a bright light illuminating the scene, and the inevitable person flinging up their arms. However, apart from the light, which is possibly reflected in Guernica’s central electric bulb, the significance of this painting possibly lies more in its emotional meaning for Picasso, rather than as a direct artistic source [18].

One external source that is commonly cited as an influence [16] is Rubens’ An Allegory Showing the Effects of War (Horrors of War) (1638) (Fig 3) This work certainly has some iconographic and compositional parallels with Guernica. A mirror image of Rubens’ work includes, from left to right, a weeping woman with a child in her arms; a flying “Fury of War” with a piece of clothing draped over her arm and holding out a torch; a upwards-facing woman with arms outstretched; and a building with an open door. All have equivalents in Guernica, and it may well be that Picasso has obtained inspiration there, particularly as he is known to have admired Rubens’s works.

Another possible source is Goya’s 3rd May, 1808 (Execution of the Defenders of Madrid, 3rd May, 1808). Like Guernica, this depicts a Spanish wartime massacre at night [17], with a bright light illuminating the scene, and the inevitable person flinging up their arms. However, apart from the light, which is possibly reflected in Guernica’s central electric bulb, the significance of this painting possibly lies more in its emotional meaning for Picasso, rather than as a direct artistic source [18].

Further examples can be multiplied. For example, it has been suggested that some of the imagery in Guernica has its genesis in depictions of the Christian Crucifixion, a subject that had long interested Picasso. The main evidence includes the warrior’s wide flung arms (possibly more evident in some of the early sketches), possible stigmata, the spear in the horse’s side and a Pieta-like pose [19]. Similarly, Reni’s Massacre of the Innocents (1611) features the expected terrified mothers with babies, wildly flung arms and looming buildings on the right. However, at some point this sort of exercise starts to have diminishing returns. There is a limit to the number of ways that one can depict, say, a wailing woman holding a dead infant. Should we be surprised, for example, that the image in Guernica is similar to many others by earlier artists in which the mother’s mouth is open and her head thrown back? [20]

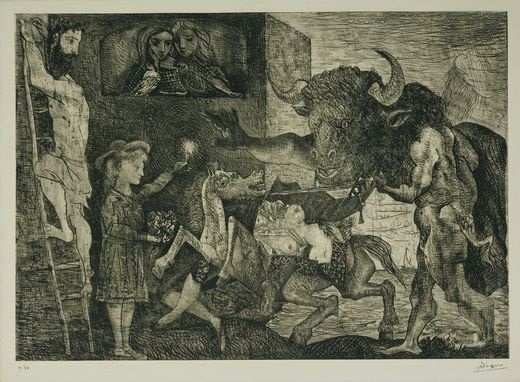

Despite this reservation, a possible external source for the wraith-like lamp-bearer in Guernica should be mentioned. The importance of this striking image to Picasso is demonstrated by the fact that it survives virtually unchanged right from his first day of sketching for the painting (Fig 5). The lamp-bearer’s role has conventionally been assumed to be that of the bearer of enlightenment, or freedom, along the same lines as the Statue of Liberty. Her genesis has therefore often been taken to be a character such as the little girl [21] who gamely holds up a cautionary light to the Minotaur in Minotauromachy.(Fig 4). However, Fisch, among some other speculative hypotheses, suggests that the lamp-bearer is actually meant to convey a mythical Fury – an avenging spirit of retributive justice [22]. If so, its genesis may lie elsewhere [23].

News reports and images of Gernika still burning at night may have influenced Picasso in giving Guernica an apparently night-time setting [24]. Alternatively, he may have simply considered that the depiction of death by night would be particularly frightening. Other possibilities are that he may have wished to present a black and white picture, not necessarily a nocturnal one, because it would have the immediacy of a news report, or because it offered the opportunity for dramatic contrasts suggestive of good versus evil, or was evocative of a funeral or even because it was reminiscent of fellow-Spaniard Goya’s sketches in the Disasters of War series [25].

More direct sources for Guernica can, of course, be identified in some of Picasso’s own earlier works. The most obvious of these concern the central images of the bull and the horse. It seems clear that these are ultimately derived from the quintessential Spanish spectacle of bullfighting. Picasso had been doing bullfight-themed pictures since his childhood. Over time, his depictions increase the violent, painful, bloodthirsty and penetrative sexual aspects of the bull’s attacks on the almost sacrificial horse. By the early 1930s, the animals were being depicted outside the bullfighting context, and were starting to separate from each other. They also began to assume even more human physical characteristics, sometimes appearing to take on some of attributes of Picasso, his alienated wife Olga and his lover Marie-Therese [26]. About this time, the mythical Minotaur also appears, with its combination of bull’s head and man’s torso, and appears to assume certain divergent aspects of Picasso’s own personality – sometimes loving, sometimes beastly [27].

Some of these strands appear again in Minotauromachy (1935) (Fig 4), which bears some striking similarities to Guernica. As originally painted (before reversal as an etching), it showed a Minotaur on the left, a dying horse, a little girl with an outstretched arm holding a burning candle and a bunch of flowers, and a building with a window on the right. Iconographically and compositionally, these can be likened to the bull, horse, and lamp-bearer and buildings in Guernica [28].

News reports and images of Gernika still burning at night may have influenced Picasso in giving Guernica an apparently night-time setting [24]. Alternatively, he may have simply considered that the depiction of death by night would be particularly frightening. Other possibilities are that he may have wished to present a black and white picture, not necessarily a nocturnal one, because it would have the immediacy of a news report, or because it offered the opportunity for dramatic contrasts suggestive of good versus evil, or was evocative of a funeral or even because it was reminiscent of fellow-Spaniard Goya’s sketches in the Disasters of War series [25].

More direct sources for Guernica can, of course, be identified in some of Picasso’s own earlier works. The most obvious of these concern the central images of the bull and the horse. It seems clear that these are ultimately derived from the quintessential Spanish spectacle of bullfighting. Picasso had been doing bullfight-themed pictures since his childhood. Over time, his depictions increase the violent, painful, bloodthirsty and penetrative sexual aspects of the bull’s attacks on the almost sacrificial horse. By the early 1930s, the animals were being depicted outside the bullfighting context, and were starting to separate from each other. They also began to assume even more human physical characteristics, sometimes appearing to take on some of attributes of Picasso, his alienated wife Olga and his lover Marie-Therese [26]. About this time, the mythical Minotaur also appears, with its combination of bull’s head and man’s torso, and appears to assume certain divergent aspects of Picasso’s own personality – sometimes loving, sometimes beastly [27].

Some of these strands appear again in Minotauromachy (1935) (Fig 4), which bears some striking similarities to Guernica. As originally painted (before reversal as an etching), it showed a Minotaur on the left, a dying horse, a little girl with an outstretched arm holding a burning candle and a bunch of flowers, and a building with a window on the right. Iconographically and compositionally, these can be likened to the bull, horse, and lamp-bearer and buildings in Guernica [28].

However, given that the relationship and significance of the bull and the horse have constantly evolved, it is not safe to assume that they continue to bear the same meanings in the totally different context that Guernica presents [29]. This is why it may be a mistake to say that by using them Picasso has necessarily introduced either the theme of the bullfight, or the war of the sexes, into the painting. But what do they represent here? Many possibilities have been suggested – for example, the bull might represent darkness and brutality, Franco, Spain, the Spanish people, Picasso himself, or just a bull. The horse might represent suffering, Franco, the women in Picasso’s life, or just a horse. There is possibly no “correct” answer to this question [30].

Another possible contribution to the genesis of Guernica was the series of sketches on the theme of the Artist in his Studio, which had been Picasso’s initial response to the commission [31]. The sketches show some similarities to Guernica – a central triangular composition, a window in the building on the right, a vertical clenched fist (included but dismissed in sketches for Guernica), and a partially open door [32]. In addition, the painting was to be flanked by two sculptured busts of women, which, arguably, would subsequently be reflected in the two wailing women at the edges of Guernica [33].

Stylistically, it seems clear that Picasso has drawn widely from his own repertoire in creating Guernica. The cubist fracturing of planes that occurs throughout the painting presents the viewer with an unrealistic lack of depth, and with lighting effects that highlight the figures in an empirically improbable way. This creates in the viewer a general disorientation as to where the characters are in space [34], an impression heightened by the obscurity of the background, and the ambiguity about whether the scene is intended to be external or internal [35]. The styles and reality levels of the figures themselves also vary – the bull, the lamp and the light bulb are relatively naturalistic, whereas various other characters are presented in an extremely expressive style [36]; so, for example, the warrior is a metamorphic mixture of statue and flesh, and the classically featured lamp bearer is wraith-like. All figures, no matter what their orientation, have both eyes staring out of the picture plane in the cubist fashion, contributing to the atmosphere of uncontrolled alarm. When added to the deliberate incongruity of different eras depicted in the painting [37], these elements contribute to an overall uncertainty in the viewer, reflective of the disordering effects of the bombing [38].

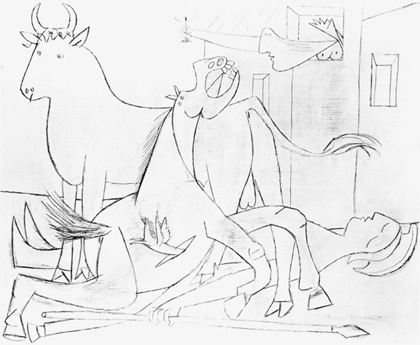

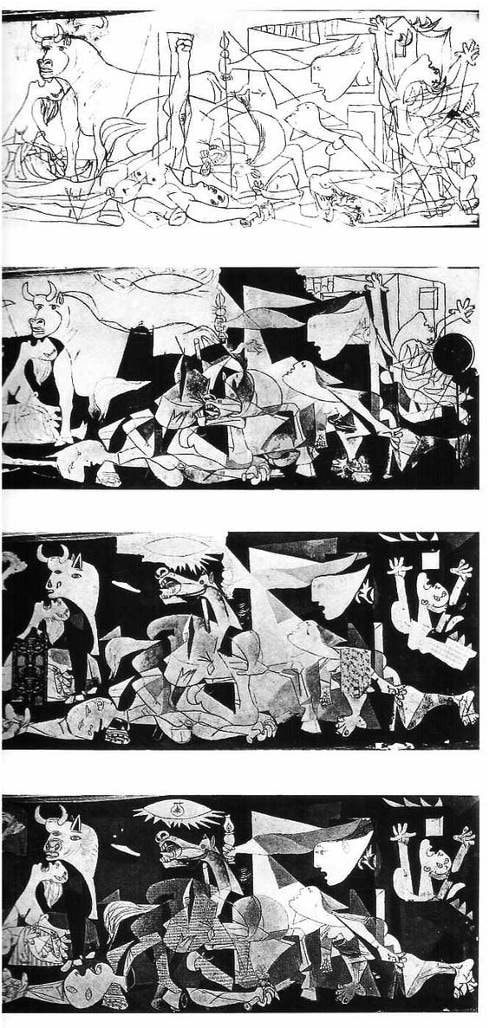

The final stage in the artistic genesis of Guernica consists of the preparatory sketches and drafts that Picasso executed from 1 May 1937 onwards. Thanks to a progressive photographic record kept by his lover Dora Maar [39], the changes in the concept can be traced. These have been analysed elsewhere in exhaustive detail [40] but, for present purposes, there are some essential points. The first is that right from the first day of sketching, many of the basic elements of the finished work were present, and also in roughly similar positions (Fig 5). A bull is on the left, a contorted horse is in the centre, a lamp bearer swoops in from a window in a building on the right, a dead warrior lies prone.

Another possible contribution to the genesis of Guernica was the series of sketches on the theme of the Artist in his Studio, which had been Picasso’s initial response to the commission [31]. The sketches show some similarities to Guernica – a central triangular composition, a window in the building on the right, a vertical clenched fist (included but dismissed in sketches for Guernica), and a partially open door [32]. In addition, the painting was to be flanked by two sculptured busts of women, which, arguably, would subsequently be reflected in the two wailing women at the edges of Guernica [33].

Stylistically, it seems clear that Picasso has drawn widely from his own repertoire in creating Guernica. The cubist fracturing of planes that occurs throughout the painting presents the viewer with an unrealistic lack of depth, and with lighting effects that highlight the figures in an empirically improbable way. This creates in the viewer a general disorientation as to where the characters are in space [34], an impression heightened by the obscurity of the background, and the ambiguity about whether the scene is intended to be external or internal [35]. The styles and reality levels of the figures themselves also vary – the bull, the lamp and the light bulb are relatively naturalistic, whereas various other characters are presented in an extremely expressive style [36]; so, for example, the warrior is a metamorphic mixture of statue and flesh, and the classically featured lamp bearer is wraith-like. All figures, no matter what their orientation, have both eyes staring out of the picture plane in the cubist fashion, contributing to the atmosphere of uncontrolled alarm. When added to the deliberate incongruity of different eras depicted in the painting [37], these elements contribute to an overall uncertainty in the viewer, reflective of the disordering effects of the bombing [38].

The final stage in the artistic genesis of Guernica consists of the preparatory sketches and drafts that Picasso executed from 1 May 1937 onwards. Thanks to a progressive photographic record kept by his lover Dora Maar [39], the changes in the concept can be traced. These have been analysed elsewhere in exhaustive detail [40] but, for present purposes, there are some essential points. The first is that right from the first day of sketching, many of the basic elements of the finished work were present, and also in roughly similar positions (Fig 5). A bull is on the left, a contorted horse is in the centre, a lamp bearer swoops in from a window in a building on the right, a dead warrior lies prone.

The second point is that as the sketches continue, additional features are added to fill the enormous canvas and refine the composition. Two distressed women are added at the sides. The triangular composition becomes more firmly anchored by the warrior at the base, the crawling woman provides the lower angle of the triangle on the right, and the horse’s neck and head provide the vertical focus. The third aspect is that during the sketching stage, Picasso experiments with various things, abandoning some or integrating others into the painting. It is significant that many of those that are rejected are those that could be considered clichéd, unreal or overtly political [41].

Picasso generally has also avoided blood and gore, with the viewer being spared, for example, the graphic results of the evisceration of the horse. This suggests that, despite his passion, Picasso was exercising considerable restraint, mirroring the restraint he exhibited in his choice of theme and title. The final, crucial, point is that Picasso is willing to alter things if they do not suit the overall composition [42].

The career begins

The Spanish Pavilion where Guernica was first exhibited was an overt exercise in propaganda by the republican government, designed to show the world that it was still in power, and remind them of the horrors that the Spanish people had been experiencing at the hands of the Franco forces. Art such as Guernica was one of its weapons [43].

Art was also being used in a similar way by the opposing forces. Franco had arranged for a rival display of traditional nationalist art at the Vatican Pavilion. This display rather predictably included grandiose busts, heroic equestrian statues and portraits of Franco [44]. The German government, which similarly despised modern art, especially by leftists, derided Guernica as a painting that could have been done by a four year old [45].

In this highly politicised atmosphere, Guernica therefore came as somewhat of a disappointment to many republican sympathisers who were hoping it would contain an overt and specific propaganda message [46]. In fact, as we have seen, the contents of Guernica did not refer specifically either to Gernika or to bombing by fascists at all. In view of this, the question arises as to how it was that Guernica itself came to become so intensely politicised.

The first point to make is the fact that Guernica was an enormous, striking and distinctive work by a controversial, famous artist. These factors meant that it had the potential to become instantly recognisable by a sizeable part of the public – an important and almost indispensable factor in any political “career”[47]. The second point is that Guernica played a role in the politicisation of Picasso himself, and in the way others saw him. Before 1936, Picasso had not been known for explicit political statements. In fact, his friend Kahnweiler described him as the least political person he knew, and the pre-Guernica Picasso himself said, “I will never make art with the preconceived idea of serving the interests of the political, religious or military art of a country”[48].

However, as the civil war continued, its personal impact on Picasso became greater. He accepted a public role as Director of the Prado Museum, and his financial contributions to the cause, the clenched fist salute in his drop curtain for the ballet Le 14 Juillet, and his uncompromising Dream and Lie of Franco, clearly indicated the way he was going. But it was the bombing, and his emotional identification with it through Guernica itself [49], that irretrievably committed him to a political path. This led to his dedicated participation in anti-war movements, his eventual membership of the French communist party, his enthusiastic support of communist regimes and the ultimate embarrassment of his Portrait of Stalin [50].

Beyond these two factors, however, it was the very fact of Guernica’s outward “neutrality”, coupled with the tide of events, that would prove to be crucial to its politicisation. For example, it was Guernica’s anti-Franco associations, rather than its actual content, that enabled it to have a role in the ongoing struggle by democratic forces in Spain after Franco’s victory in the civil war. In some ways, this development was due to the actions of Franco himself. Franco furiously disputed that there had been any bombing at all, claiming that the town had been burned by leftists who had then tried to shift the blame to him. Once Franco gained power, this blatant untruth became the official line for many years, thus ensuring that the debate would continue to fester [51].

Furthermore, notwithstanding the painting’s silence in attributing blame, Franco’s severe censoring of it [52] and his increasingly venomous attacks on Picasso, served to highlight the painting’s continuing association with the specific issue of Gernika and with anti-Franco sentiment in general. In these circumstances, it was natural that Guernica would become a symbol of protest for those continuing to resist Franco. Franco’s attitude also made it clear that the painting would not be safe in Spain, and its resultant overseas travels and publicity only served to further heighten its impact, no doubt to Franco’s increasing annoyance. Picasso famously commented later that Guernica’s exile at MoMA meant that he had the pleasure of making a political statement in the middle of New York City every day [53].

Art was also being used in a similar way by the opposing forces. Franco had arranged for a rival display of traditional nationalist art at the Vatican Pavilion. This display rather predictably included grandiose busts, heroic equestrian statues and portraits of Franco [44]. The German government, which similarly despised modern art, especially by leftists, derided Guernica as a painting that could have been done by a four year old [45].

In this highly politicised atmosphere, Guernica therefore came as somewhat of a disappointment to many republican sympathisers who were hoping it would contain an overt and specific propaganda message [46]. In fact, as we have seen, the contents of Guernica did not refer specifically either to Gernika or to bombing by fascists at all. In view of this, the question arises as to how it was that Guernica itself came to become so intensely politicised.

The first point to make is the fact that Guernica was an enormous, striking and distinctive work by a controversial, famous artist. These factors meant that it had the potential to become instantly recognisable by a sizeable part of the public – an important and almost indispensable factor in any political “career”[47]. The second point is that Guernica played a role in the politicisation of Picasso himself, and in the way others saw him. Before 1936, Picasso had not been known for explicit political statements. In fact, his friend Kahnweiler described him as the least political person he knew, and the pre-Guernica Picasso himself said, “I will never make art with the preconceived idea of serving the interests of the political, religious or military art of a country”[48].

However, as the civil war continued, its personal impact on Picasso became greater. He accepted a public role as Director of the Prado Museum, and his financial contributions to the cause, the clenched fist salute in his drop curtain for the ballet Le 14 Juillet, and his uncompromising Dream and Lie of Franco, clearly indicated the way he was going. But it was the bombing, and his emotional identification with it through Guernica itself [49], that irretrievably committed him to a political path. This led to his dedicated participation in anti-war movements, his eventual membership of the French communist party, his enthusiastic support of communist regimes and the ultimate embarrassment of his Portrait of Stalin [50].

Beyond these two factors, however, it was the very fact of Guernica’s outward “neutrality”, coupled with the tide of events, that would prove to be crucial to its politicisation. For example, it was Guernica’s anti-Franco associations, rather than its actual content, that enabled it to have a role in the ongoing struggle by democratic forces in Spain after Franco’s victory in the civil war. In some ways, this development was due to the actions of Franco himself. Franco furiously disputed that there had been any bombing at all, claiming that the town had been burned by leftists who had then tried to shift the blame to him. Once Franco gained power, this blatant untruth became the official line for many years, thus ensuring that the debate would continue to fester [51].

Furthermore, notwithstanding the painting’s silence in attributing blame, Franco’s severe censoring of it [52] and his increasingly venomous attacks on Picasso, served to highlight the painting’s continuing association with the specific issue of Gernika and with anti-Franco sentiment in general. In these circumstances, it was natural that Guernica would become a symbol of protest for those continuing to resist Franco. Franco’s attitude also made it clear that the painting would not be safe in Spain, and its resultant overseas travels and publicity only served to further heighten its impact, no doubt to Franco’s increasing annoyance. Picasso famously commented later that Guernica’s exile at MoMA meant that he had the pleasure of making a political statement in the middle of New York City every day [53].

Rehabilitation in Spain

Much later, as Franco’s personal power waned, the official attitude softened somewhat [54]. By 1969, official attitudes had evolved to the extent that Franco publicly claimed that the painting should be relocated in Spain [55]. After Franco’s death in 1975, a political consensus developed that this should be expedited. The position was, however, complicated by long-running questions as to the true ownership of the painting, its suitability for travel, and the conditions of its “return”[56]. Picasso had delegated authority to his French attorney, saying that the painting could not be returned until public liberties had been restored in Spain, an issue that obviously created political tensions. Picasso’s heirs also claimed to be involved. His daughter Paloma, for example, had some success in demanding, as a price of her support, the freeing of certain actors who had been jailed for participation in a satirical anti-establishment play. She also unsuccessfully argued that public liberties could not be said to have been restored until there had been reform of the divorce laws [57]. MoMA, which stood to lose one of its star attractions, also had its own interests to protect.

For Spaniards, the issue had become a matter of national pride, with many feeling resentment that a judgment on Spain’s political health and maturity was in the hands of foreigners. Even when the decision had finally been made to return the painting in 1981 (marking the 100th anniversary of Picasso’s birth), there was a political wrangle over its correct location, though Madrid was always going to be the choice of the government. Its ultimate return was generally seen as a sign of healing. Just as its exile had been symptomatic of Spain’s inability to live in peace, now its return represented a restoration of national dignity.

Despite this apparent contribution to unifying left and right forces in Spain, Guernica has been, and continues to be, an emblem of the political divisions between the central Madrid government and the Basques who believe that they are the objects of political and social discrimination. For obvious reasons, the painting has come to symbolise the bombing, and the painting has understandably deeper and more specific meaning for Basques than for “outsiders”. During the 1950s many Basques apparently had posters of Guernica on their walls, next to the Last Supper [58].

Basques were therefore incensed with Franco’s attitudes to the painting [59], and with its location in Madrid [60]. Basque feeling on the issue has been summarised as “we gave the dead, while you get the painting” [61]. The painting also still forms an essential role in Basque commemorations of the bombing [62]. Continuing attempts by the Basque congress to obtain even temporary custody of the painting have been fruitless [63]. While it is difficult to know how much of the dispute over the painting is attributable to genuine passion and how much is attributable to grandstanding by local politicians, either way illustrates that the painting still has regional political potency [64].

For Spaniards, the issue had become a matter of national pride, with many feeling resentment that a judgment on Spain’s political health and maturity was in the hands of foreigners. Even when the decision had finally been made to return the painting in 1981 (marking the 100th anniversary of Picasso’s birth), there was a political wrangle over its correct location, though Madrid was always going to be the choice of the government. Its ultimate return was generally seen as a sign of healing. Just as its exile had been symptomatic of Spain’s inability to live in peace, now its return represented a restoration of national dignity.

Despite this apparent contribution to unifying left and right forces in Spain, Guernica has been, and continues to be, an emblem of the political divisions between the central Madrid government and the Basques who believe that they are the objects of political and social discrimination. For obvious reasons, the painting has come to symbolise the bombing, and the painting has understandably deeper and more specific meaning for Basques than for “outsiders”. During the 1950s many Basques apparently had posters of Guernica on their walls, next to the Last Supper [58].

Basques were therefore incensed with Franco’s attitudes to the painting [59], and with its location in Madrid [60]. Basque feeling on the issue has been summarised as “we gave the dead, while you get the painting” [61]. The painting also still forms an essential role in Basque commemorations of the bombing [62]. Continuing attempts by the Basque congress to obtain even temporary custody of the painting have been fruitless [63]. While it is difficult to know how much of the dispute over the painting is attributable to genuine passion and how much is attributable to grandstanding by local politicians, either way illustrates that the painting still has regional political potency [64].

Guernica goes international

Guernica has also played significant political roles outside Spain. In England, when it originally toured in 1938 [65], it was championed by the Opposition leader in a bid to build support for his anti-appeasement policy, though with little tangible result. On its arrival in America, it was greeted with hostility from some right-wing politicians. motivated partly by the fact that the work represented “modern” art, and also because of the suspicion that Picasso was communist-inspired. Later, in an America in the grip of the Cold War, with Picasso’s communism now an acknowledged fact, the painting was violently attacked by anti-communist politicians [66]. People who had been associated with bringing the work to America also became the subject of investigation by the FBI and the House Un-American Activities Committee [67].

Guernica’s association with general anti-war sentiment also meant that it has had continuing international relevance for an era in which wars, and other acts of mass terror, became more publicly controversial. It has been claimed that it has become the world’s most recognised symbol of war’s brutality [68], being used in war contexts such as the Vietnam War, the 50th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, and even fictional conflicts set in the future [69]. The full-size tapestry replica which appears at the United Nations building in New York was famously covered up ten days before Colin Powell was due to deliver an address in front of it foreshadowing the United States’ invasion of Iraq. The official reason was that the detail of the painting was too distracting to be a suitable backdrop for news conferences. However, the timing raised dark and cynical suspicions that it was done to save possible embarrassment to the US government [70]. It is also reported that in the wake of the 2004 terrorist bombings of Madrid railway station, countless thousands of Madrid residents made the short pilgrimage to view Guernica in an eerie and reverential silence [71].

Guernica’s association with general anti-war sentiment also meant that it has had continuing international relevance for an era in which wars, and other acts of mass terror, became more publicly controversial. It has been claimed that it has become the world’s most recognised symbol of war’s brutality [68], being used in war contexts such as the Vietnam War, the 50th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, and even fictional conflicts set in the future [69]. The full-size tapestry replica which appears at the United Nations building in New York was famously covered up ten days before Colin Powell was due to deliver an address in front of it foreshadowing the United States’ invasion of Iraq. The official reason was that the detail of the painting was too distracting to be a suitable backdrop for news conferences. However, the timing raised dark and cynical suspicions that it was done to save possible embarrassment to the US government [70]. It is also reported that in the wake of the 2004 terrorist bombings of Madrid railway station, countless thousands of Madrid residents made the short pilgrimage to view Guernica in an eerie and reverential silence [71].

Adaptation and exploitation

Guernica’s capacity to become a focus in such a variety of political disputes is due largely to its adaptability. Any viewer, as long as they are against suffering, is free to read whatever they wish into the work. In this respect, the restraint shown in the choice of theme and contents can be contrasted with other, more blatantly political works by Picasso, such as Massacre in Korea (1951). The unsubtle depiction in such paintings of specific events or persons, and their consequent disclosure of Picasso’s limited point of view, work strongly against their being adopted as symbols in other contexts [72].

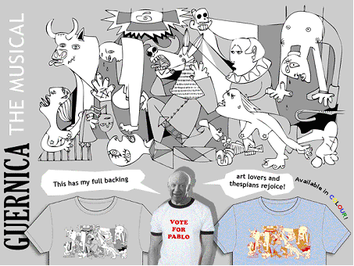

However, Guernica’s adaptability can also be its Achilles heel, as it means that its message is in danger of becoming so diluted as to lose its potency. It has become so familiar that it is in danger of becoming too respectable [73]. Certainly it has become vulnerable to modishness [74], personification [75], commercialisation (for example, in a Vogue advertisement), commoditisation and trivialisation (Fig 6). At the other extreme, it has become the subject of inappropriate veneration. So, for example, the packing case that transported Guernica to Spain from New York in 1981 was apparently displayed like a holy relic at a Madrid museum [76].

However, Guernica’s adaptability can also be its Achilles heel, as it means that its message is in danger of becoming so diluted as to lose its potency. It has become so familiar that it is in danger of becoming too respectable [73]. Certainly it has become vulnerable to modishness [74], personification [75], commercialisation (for example, in a Vogue advertisement), commoditisation and trivialisation (Fig 6). At the other extreme, it has become the subject of inappropriate veneration. So, for example, the packing case that transported Guernica to Spain from New York in 1981 was apparently displayed like a holy relic at a Madrid museum [76].

Now, virtually anyone in the political or the cultural spectrum can get away with embracing the work, or at least can think they can – perhaps its most bizarre manifestation was as part of a recruitment campaign for Germany’s post-war armed forces [77].

The question must therefore be raised as to its modern political role. Despite colourful claims that it “shaped history”[78], and its continuing role as a Basque rallying point, it would seem that its strength outside Spain does not really lie in changing people’s minds or the course of events. Rather, its principal appeal is – and possibly always has been – to the already converted. Guernica’s main political function appears to be as a striking and convenient reminder of the horrors of war (especially wars started by others), coupled with a comforting function as an expression of condolence when life has been lost.□

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2017

We welcome your comments on this article

The question must therefore be raised as to its modern political role. Despite colourful claims that it “shaped history”[78], and its continuing role as a Basque rallying point, it would seem that its strength outside Spain does not really lie in changing people’s minds or the course of events. Rather, its principal appeal is – and possibly always has been – to the already converted. Guernica’s main political function appears to be as a striking and convenient reminder of the horrors of war (especially wars started by others), coupled with a comforting function as an expression of condolence when life has been lost.□

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2017

We welcome your comments on this article

End Notes

1. For good accounts of the Spanish Civil War, see Antony Beevor’s The Battle for Spain, Phoenix, London, 2006; Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War (4th revd edn), Penguin Books, London, 2003; and Richard Baxell, Unlikely Warriors: The British in the Spanish Civil War and the Struggle against Fascism, Aurum, 2012.

2. The delegation was no doubt attracted to Picasso because of his role as Spain’s greatest living artist, his recent appointment as a Director of the Prado, his previous financial support for the Republicans, his ideological stance, and of course the convenience of his being resident in Paris.

3. Postcards of the etchings were sold as a fundraiser at the World Fair. The quotation is from Picasso’s surreal poem that he wrote to accompany the etchings.

4. This was a familiar theme for Picasso, most recently seen in the Vollard Suite (1930-36).

4A. For a vivid eyewitness account, see Monks, Noel, Eyewitness, Frederick Muller, 1955. Graphic reports by Paris-Soir journalist Louis Delaprée of Franco's bombing of Madrid had also been published in January 1937.

5. This is the Basque spelling, pronounced Gair-NEE-kuh. The French and Spanish spelling is Guernica. I am using Gernika for the town and Guernica for the painting.

6. A cousin of the First World War flying ace Baron von Richthofen.

7. Estimates at the time were as high as 1,654 dead, but recent research suggests that the death toll was more likely to have been between 200 and 300 (Beevor, op cit, at 258).

8. A film on Picasso’s emotional upheaval during the precise period when Guernica was being painted is scheduled to be released in 2014 or 2015. Entitled 33 Dias, it will be directed by Carlos Saura and is expected to star Antonio Banderas and Gwyneth Paltrow.

9. Goya’s The Disasters of War sketches of 1810-20 are obvious predecessors.

10. The poet Federico Garcia Lorca once said that “Spain is the only country where death is a natural spectacle…{A] dead person in Spain is more alive when dead than is the case anywhere else – his profile cuts like the edge of a barber’s razor” (cited in Chipp, H B, Picasso’s Guernica: History, Transformation, Meaning, London: Thames and Hudson, 1989 at 45). Lorca also described the Spanish concept of duende – the mixture of bravado and fatalism in the face of death that pervades such spectacles as the bullfight. For a discussion of the impact on Picasso of the depiction of agony in Matthias Grűnewald's Crucifixion panel in the Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-1516), see Apostolos-Cappadona, D, "The Essence of Agony: Grűnewald’s Influence on Picasso", Artibus et Historiae, Vol 13, No 26, 1992 31-47.

11. The title itself is a model of understated restraint – no Horrors of Guernica for Picasso. He did not display the same restraint in his later, far less successful, Massacre in Korea (1951)

12. The night time setting may have been based on news images, but the bombing actually occurred during the day. The background buildings could possibly be interpreted as the surrounds of the Gernika marketplace, but are generic. The nature of the disaster is also not clear, with hints only that there was fire involved. For example, the bull’s tail superficially resembles a plume of smoke, but this form of tail is common in earlier works by Picasso, such as in the Vollard Suite. Such specific references as there are to fighting – a warrior bearing a sword, a speared horse – in fact point away from the particular circumstances of the bombing. On the other hand, there is the possibly apocryphal story about a Nazi officer who, on seeing a photograph of Guernica in Picasso's apartment, asked "Did you do this?". "No," Picasso replied, "You did."

13. In May 1937, Picasso announced: “In the picture I am now working on and that I will call Guernica, and in all my recent work, I clearly express my loathing for the military caste that has plunged Spain into a sea of suffering and death”. Quoted in Martin, R, Picasso’s War, London: Pocket Books, 2004 at 3.

14. A possible reason for this outward neutrality of content and attitude may lie in Picasso’s apparent aversion to blatant propagandising. Of course, it could also be due to a far-sighted calculation by Picasso that this would enable Guernica to be used as a propaganda weapon in other contexts.

15. Although the issue of “source hunting” is controversial, Picasso is one artist that particularly invites such an historical approach. As Arnheim concedes, Picasso himself places Guernica in a time perspective by arranging for Dora Maar to record and photograph every step in its development. He also explicitly identifies some of his paintings as variations on previous works by others (as in his series based on Velasquez’ Las Meninas), and freely and openly borrows motifs. See Arnheim, R , “Book Review: Picasso’s Guernica after Rubens’ Horrors of War by Alice Tankard”, Leonardo Vol 18, No 2, 116.

16. For example, Fisch, E, ‘Guernica’ by Picasso: A Study of the Picture and its Content, Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1998 at 55. See also the work by Tankard cited at note 15.

17. In fact, the bombing of Gernika took place in daylight.

18. A more direct link could be made between Goya’s work and Picasso’s overtly propagandistic Massacre in Korea (1951). Another possible influence on Picasso may have been Benedetto Cervi Pavese’s Relief Depicting a Procession to a Contest (1531-2), which had come into the Parisian news in February 1937 after being targeted by an attack at the Prado (Gijs van Hensbergen, Death, destruction and deity: Painting Guernica, The Art Newspaper, 1 April 2017).

19. Other suggested evidence includes the dislocation of the warrior’s arms, which is said to be reminiscent of Picasso’s 1932 sketches of the Crucifixion inspired by Matthias Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-15); and the positioning of the two women as mourners round a triangular scene of suffering. See Chipp, op cit at 112, 124; Russell, F D, Picasso’s Guernica: The Labyrinth of Narrative and Vision, Montclair: Allanheld and Schram, 1980 at 16.

20. However, such similarities are evidently considered to be significant by Chipp, op cit at 91. Of course, there is the legitimate possibility that Picasso may have intended these as deliberate homages to painters he admired.

21. Like the lamp-bearer, the little girl has the features of Picasso’s lover Marie-Therese.

22. In Greek and Roman mythology, the Furies were avenging spirits of retributive justice whose task was to punish crimes outside the reach of human justice, particularly where crimes against the family were involved. This actually seems quite an appropriate description of Picasso’s likely perception of Franco’s crimes against his fellow Spaniards at Gernika. Given that the Furies were typically described as flying, with flaming torches, and the association becomes at least possible. It is interesting that Rubens specifically identifies a torch-bearing, arm-draped Fury in his Horrors of War. However, his Fury looks like a manic witch, quite unlike the classically featured lamp-bearer in Guernica. One possible explanation could be that Picasso has married the two concepts.

23. For example, it may be relevant that a flying “angel” unchaining war, with outstretched arm, was depicted in a work by William Blake that was evidently on exhibition in Paris just two months before Picasso started working on Guernica (see Fisch, op cit at 58).

24. See note 4A. The hatching on the horse may also have been intended to suggest newsprint. Alternatively, it could have been meant to suggest gravestones, or it may just have been a compositional device designed to enable the viewer to more easily make out the shape of the horse in the general confusion of figures. See Chipp, op cit at 133.

25. Chipp, op cit, 105. There are actually some subtle tones of pale blue in the painting. This may be attributable to the way the canvas was primed: van Hensbergen, op cit note 18.

26. For example, Femme Torero (1934). It is plausible that Picasso is depicting himself in these etchings as the bull seducing the nude representing Marie-Therese, with Olga being represented by the horse being trampled underfoot. See Chipp, op cit at 52.

27. The Minotaur was a favourite image of Surrealists. The cover of the first issue of the Surrealist journal Minotaur was executed by Picasso.

28. Some of the sketches for Guernica include a sort of “reverse Minotaur”, with a man’s face on a bull’s body. In Guernica itself, the eyes of the bull are strikingly human (even Picasso-like?), compared to those of the horse.

29. It is arguable that the spear in the horse is an oblique reference to the lance used in bullfighting. This appears unlikely. A bullfight involves the lancing of the bull, not the horse. In addition, it seems clear from the arrow-headed tip of the implement that it is a spear, not a bullfighting lance. Perhaps, however, an alternative argument in favour of the bullfight context could be mounted on the basis that Guernica represents a world turned upside down, with nothing being as it should.

30. The suggestion that the bull represented the Spanish people and the horse represented an ultimately-defeated Franco was made by Larrea (Chipp, op cit at 196). The journalist Seckler reported that Picasso told him the bull stood for darkness and brutality. Picasso also reportedly told his then-lover Francoise Gilot that horses represented the women in his life, and that he was the bull. Picasso was also the one who (rather wearily one imagines) said that the bull was just a bull and the horse was a horse. Ultimately, Picasso’s view was that “viewers are wonderfully free to make of it what they choose”: Martin, R, Picasso’s War, London: Pocket Books, 2004 at 55. He also noted that “A picture lives a life like a living creature, undergoing the changes imposed on us by our life from day to day. This is natural enough, as the picture lives only through the man [sic] who is looking at it (Chipp, op cit at 44).

31. Chipp, op cit at 58. This theme had interested Picasso for some years, and had recently appeared in the Vollard Suite (which also features images of the Minotaur, bulls and horses).

32. This was a familiar device dating back to The Three Dancers (1925). For its possible mythic significance, see note 37.

33. Picasso’s many sketches of weeping women, executed about this time, culminated in the Dora Maar inspired Weeping Woman series later in 1937.

34. It also, of course, acts more subtly to provide the central compositional triangle.

35. This ambiguity is reminiscent of the theatrical fiction of creating an exterior scene within a stage setting. It is interesting that the only comparable-sized works that Picasso had previously been involved in were his drop curtains for ballet productions such as Le 14 Juillet (Van Hensbergen, G, Guernica: The biography of a Twentieth Century Icon, New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2004 at 22). It has also been claimed that Guernica is “inconceivable” without the precedent of the drop curtains for Diaghilev (Buckley, J, Review of “Picasso and the Theatre”, The Burlington Magazine, CXLIX, April 2007 at 280). Van Hensbergen (note 18) also suggests that Picasso may have been influenced by the traditional Spanish sargas, loose canvases traditionally hung up to celebrate feasts and special holy days, or to decorate a pantheon or funerary chapel.

36. Possibly reminiscent of aspects of the Blue Period (Blunt, A, Picasso’s Guernica, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969 at 57).

37. The modernity of the electric light provides an obvious contrast to the classical allusions or myths in Picasso’s depiction of a sword-bearing warrior and a javelin transfixing the horse. Mythic origins also possibly apply to the lamp-bearer (see note 22) and the half open door, which may represent the borderline between life and death. See Hart, V, “Sigurd Lewerentz and the “Half Open Door”, Architectural History vol 39 1996 p 181.

38. Larrea claims that when Picasso asked him what a bombed town look like, Larrea answered “like a bull in a china shop” (Van Hensbergen, op cit p 33). It is true that the bull in Guernica could be seen as having a rather bemused expression, as if it is wondering why there is chaos all around it.

39. This was done at Picasso’s request..

40. Chipp, op cit Ch 6, 7; Arnheim, R, The Genesis of a Painting: Picasso’s Guernica, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973, Ch III.

41. Examples of motifs that were tried and rejected include an upright clenched fist as a vertical focus, stalks of wheat symbolic of the labour of peasants, a blinding white explosion, the use of bright colour, the use of mixed media, a Pegasus-like winged horse, a bull with an overtly human face, a red tear of blood, an overly phallic initial version of the horse’s neck, and a supposedly more overtly Christ-like pose of the warrior. Even the obvious regenerative symbol of a flower has been reduced from the bunch in Minotauromachy to the single bloom in Guernica. See Chipp, op cit at 96, 112, 116.

42. For example, the warrior assumes an extraordinary variety of positions (gender, face up/down) before Picasso is happy. The bird appears and disappears. The horse and the bull become further separated. The bull’s stance, orientation and mien alter. Chipp claims that the turning of the bull so that its tail end is on the left makes it appear more protective of the woman with the child, instead of threatening (Chipp, op cit at 123).

43. The Pavilion featured tragic photographs, art works, homages to cultural martyrs such as Gabriel Lorca, and political tracts (Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 67).

44. Later, when Franco was in full power, he sent a similar selection to the Venice Biennale in 1938 (Van Hensbergen, G, Guernica: The Biography of a Twentieth Century Icon, New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2004 at 219).

45. It also organised an exhibition in Munich that featured “degenerate” art by Jews and Bolsheviks, scattered among paintings by the inmates of a nearby mental asylum.

46. Early critics who could have been expected to have been supportive included Le Corbusier and Picasso’s journalist friend Luis Aragon. Even L’Humanite, the left wing journal, gave it only a passing reference (Martin, op cit at 118). Part of the unenthusiastic response may also have been due to the lateness of the opening of the Spanish Pavilion.

47. It is arguable that Guernica’s fame helped to educate the public into a greater acceptance that modern art may have something worthwhile to say.

48. Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 122.

49. See note 13.

50. This 1953 portrait, done from a photograph, depicted Stalin as a young man. The negative reaction to it from Soviet communists precipitated Picasso’s disillusionment with party politics. Picasso was not really cut out to be a party foot soldier. In 1948 he noted that in Russia they hated his work and loved his politics, whereas in the US the situation was reversed. Picasso commented “I’m hated everywhere. I like it that way” (van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 198).

51. Part of the reason for Franco’s denial of responsibility may have been his realisation that such an horrific event had the potential to alienate conservative and Catholic supporters, particularly overseas (Southworth, H, Guernica! Guernica! A Study of Journalism, Diplomacy, Propaganda and History, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977).

52. Franco also hated it because of its modernity.

53. Van Hensbergen, op cit at 178. For safety reasons, MoMA was Guernica’s home from about 1938 until 1981.

54. Limited references to the painting began appearing in the media. There was a 1960 exhibition of Picasso works in Barcelona, and the Picasso Museum opened there in 1963.

55. The right wing mouthpiece journal Alcazar had reproduced the painting for the first time, describing it as part of the cultural patrimony of the Spanish people, and arguing that it should be on exhibition in Spain “as proof of the definitive end of the contrasts and differences aroused by the last civil conflict” (van Hensbergen, op cit at 258). This dalliance with modernity upset sections of the extreme right. A 1971 exhibition of Picasso’s Vollard Suite was smashed up by “warriors” of Christ the King, who considered that Franco’s flirtation with Guernica symbolised the regime’s decadence and loss of direction (Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 269).

56. Strictly speaking it was not a return, as Guernica had previously never been in Spain.

57. Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 297.

58. Martin, op cit at 192.

59. They resented both his negative reaction and to his subsequent attempt to appropriate it.

60. As part of a major urban renewal related to the 1992 Olympics, it was moved from the Prado to the nearby Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Sofia, where it is currently.

61. Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 304.

62. On the 60th anniversary in 1997, the new Guggenheim Gallery was opened at Bilbao, with a special room reserved, rather forlornly, for Guernica.

63. Officially, the reason for refusal is that it is not safe to be moved, having already been moved 32 times in 60 years. A detailed infrared and ultraviolet digital scan of the work to assess its state of repair was expected to be completed in 2012 (Fotheringham, A, and Liston, E, “The Picasso that’s been in the wars”, 27 January 2012, on website of The Independent, at www.independent.co.uk; accessed 9 February 2012).

64. Madrid’s latest refusal in April 2007 to loan the painting to be shown in Gernika on the bombing’s 70th anniversary, or to send any prominent politicians to the ceremony, caused a political storm, at least regionally (Fiona Govan, "Picasso’s war classic refused leave for anniversary trip", Sydney Morning Herald 26 April 2007).

65. It arrived on the same day that Chamberlain signed the Munich agreement with Hitler. The governments in both England and France were wary of taking sides against Franco, in case it precipitated a reaction from Hitler.

66. Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 123.

67. Martin, op cit at 178. Political pressure was also placed on MoMA director Barr to either remove the painting or to neutralise its overt political significance. Barr responded by removing specific references to the Spanish Civil War (Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 186)

68. Martin, op cit at 198.

69. The 2006 film Children of Men, set in a nightmarish London of 2020, ironically showed Guernica as the looted backdrop for the headquarters of the ruthless junta running Britain – a reminder of Franco’s earlier brazen attempt to appropriate it for his own purposes. See also note 8.

70.This may be one of those issues on which people tend to believe the version they want to believe (Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 2.

71. See Simon Schama, Power of Art, London: BBC Books, 2006 at 395.

72. A similar point can be made about Dream and Lie of Franco.

73. In 1974, Guernica was defaced with the words KILL LIES ALL by an Iranian artist Tony Shrafrazi, who wanted to draw the public’s attention to atrocities in Vietnam. He argued that by his apparently vandalistic action, he was re-politicising the painting, which had over the years become too safe and respectable (Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 276)

74. In the 1960s, Guernica became a fashionable anti-establishment symbol for the Spanish young, along with posters of Ché Guevara, Joan Baez and copies of Playboy (Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 237, 239).

75. Courtesy of van Hensbergen, note 35 op cit.

76. Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 310. It has been claimed that as Guernica has become an object of holy veneration, similar to a secular Crucifixion, it has lost its political effectiveness (Comment quoted by Van Hensbergen, op cit at 273).

77. Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 187, 315. This prompted a furious denunciation by the writer Gunter Grass (The Art Newspaper Issue 8, 1 May 1991).

78. Chipp, op cit at 197.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014. 2015, 2017

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The shocking birth and amazing career of Guernica", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to Home

2. The delegation was no doubt attracted to Picasso because of his role as Spain’s greatest living artist, his recent appointment as a Director of the Prado, his previous financial support for the Republicans, his ideological stance, and of course the convenience of his being resident in Paris.

3. Postcards of the etchings were sold as a fundraiser at the World Fair. The quotation is from Picasso’s surreal poem that he wrote to accompany the etchings.

4. This was a familiar theme for Picasso, most recently seen in the Vollard Suite (1930-36).

4A. For a vivid eyewitness account, see Monks, Noel, Eyewitness, Frederick Muller, 1955. Graphic reports by Paris-Soir journalist Louis Delaprée of Franco's bombing of Madrid had also been published in January 1937.

5. This is the Basque spelling, pronounced Gair-NEE-kuh. The French and Spanish spelling is Guernica. I am using Gernika for the town and Guernica for the painting.

6. A cousin of the First World War flying ace Baron von Richthofen.

7. Estimates at the time were as high as 1,654 dead, but recent research suggests that the death toll was more likely to have been between 200 and 300 (Beevor, op cit, at 258).

8. A film on Picasso’s emotional upheaval during the precise period when Guernica was being painted is scheduled to be released in 2014 or 2015. Entitled 33 Dias, it will be directed by Carlos Saura and is expected to star Antonio Banderas and Gwyneth Paltrow.

9. Goya’s The Disasters of War sketches of 1810-20 are obvious predecessors.

10. The poet Federico Garcia Lorca once said that “Spain is the only country where death is a natural spectacle…{A] dead person in Spain is more alive when dead than is the case anywhere else – his profile cuts like the edge of a barber’s razor” (cited in Chipp, H B, Picasso’s Guernica: History, Transformation, Meaning, London: Thames and Hudson, 1989 at 45). Lorca also described the Spanish concept of duende – the mixture of bravado and fatalism in the face of death that pervades such spectacles as the bullfight. For a discussion of the impact on Picasso of the depiction of agony in Matthias Grűnewald's Crucifixion panel in the Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-1516), see Apostolos-Cappadona, D, "The Essence of Agony: Grűnewald’s Influence on Picasso", Artibus et Historiae, Vol 13, No 26, 1992 31-47.

11. The title itself is a model of understated restraint – no Horrors of Guernica for Picasso. He did not display the same restraint in his later, far less successful, Massacre in Korea (1951)

12. The night time setting may have been based on news images, but the bombing actually occurred during the day. The background buildings could possibly be interpreted as the surrounds of the Gernika marketplace, but are generic. The nature of the disaster is also not clear, with hints only that there was fire involved. For example, the bull’s tail superficially resembles a plume of smoke, but this form of tail is common in earlier works by Picasso, such as in the Vollard Suite. Such specific references as there are to fighting – a warrior bearing a sword, a speared horse – in fact point away from the particular circumstances of the bombing. On the other hand, there is the possibly apocryphal story about a Nazi officer who, on seeing a photograph of Guernica in Picasso's apartment, asked "Did you do this?". "No," Picasso replied, "You did."

13. In May 1937, Picasso announced: “In the picture I am now working on and that I will call Guernica, and in all my recent work, I clearly express my loathing for the military caste that has plunged Spain into a sea of suffering and death”. Quoted in Martin, R, Picasso’s War, London: Pocket Books, 2004 at 3.

14. A possible reason for this outward neutrality of content and attitude may lie in Picasso’s apparent aversion to blatant propagandising. Of course, it could also be due to a far-sighted calculation by Picasso that this would enable Guernica to be used as a propaganda weapon in other contexts.

15. Although the issue of “source hunting” is controversial, Picasso is one artist that particularly invites such an historical approach. As Arnheim concedes, Picasso himself places Guernica in a time perspective by arranging for Dora Maar to record and photograph every step in its development. He also explicitly identifies some of his paintings as variations on previous works by others (as in his series based on Velasquez’ Las Meninas), and freely and openly borrows motifs. See Arnheim, R , “Book Review: Picasso’s Guernica after Rubens’ Horrors of War by Alice Tankard”, Leonardo Vol 18, No 2, 116.

16. For example, Fisch, E, ‘Guernica’ by Picasso: A Study of the Picture and its Content, Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1998 at 55. See also the work by Tankard cited at note 15.

17. In fact, the bombing of Gernika took place in daylight.

18. A more direct link could be made between Goya’s work and Picasso’s overtly propagandistic Massacre in Korea (1951). Another possible influence on Picasso may have been Benedetto Cervi Pavese’s Relief Depicting a Procession to a Contest (1531-2), which had come into the Parisian news in February 1937 after being targeted by an attack at the Prado (Gijs van Hensbergen, Death, destruction and deity: Painting Guernica, The Art Newspaper, 1 April 2017).

19. Other suggested evidence includes the dislocation of the warrior’s arms, which is said to be reminiscent of Picasso’s 1932 sketches of the Crucifixion inspired by Matthias Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-15); and the positioning of the two women as mourners round a triangular scene of suffering. See Chipp, op cit at 112, 124; Russell, F D, Picasso’s Guernica: The Labyrinth of Narrative and Vision, Montclair: Allanheld and Schram, 1980 at 16.

20. However, such similarities are evidently considered to be significant by Chipp, op cit at 91. Of course, there is the legitimate possibility that Picasso may have intended these as deliberate homages to painters he admired.

21. Like the lamp-bearer, the little girl has the features of Picasso’s lover Marie-Therese.

22. In Greek and Roman mythology, the Furies were avenging spirits of retributive justice whose task was to punish crimes outside the reach of human justice, particularly where crimes against the family were involved. This actually seems quite an appropriate description of Picasso’s likely perception of Franco’s crimes against his fellow Spaniards at Gernika. Given that the Furies were typically described as flying, with flaming torches, and the association becomes at least possible. It is interesting that Rubens specifically identifies a torch-bearing, arm-draped Fury in his Horrors of War. However, his Fury looks like a manic witch, quite unlike the classically featured lamp-bearer in Guernica. One possible explanation could be that Picasso has married the two concepts.

23. For example, it may be relevant that a flying “angel” unchaining war, with outstretched arm, was depicted in a work by William Blake that was evidently on exhibition in Paris just two months before Picasso started working on Guernica (see Fisch, op cit at 58).

24. See note 4A. The hatching on the horse may also have been intended to suggest newsprint. Alternatively, it could have been meant to suggest gravestones, or it may just have been a compositional device designed to enable the viewer to more easily make out the shape of the horse in the general confusion of figures. See Chipp, op cit at 133.

25. Chipp, op cit, 105. There are actually some subtle tones of pale blue in the painting. This may be attributable to the way the canvas was primed: van Hensbergen, op cit note 18.

26. For example, Femme Torero (1934). It is plausible that Picasso is depicting himself in these etchings as the bull seducing the nude representing Marie-Therese, with Olga being represented by the horse being trampled underfoot. See Chipp, op cit at 52.

27. The Minotaur was a favourite image of Surrealists. The cover of the first issue of the Surrealist journal Minotaur was executed by Picasso.

28. Some of the sketches for Guernica include a sort of “reverse Minotaur”, with a man’s face on a bull’s body. In Guernica itself, the eyes of the bull are strikingly human (even Picasso-like?), compared to those of the horse.

29. It is arguable that the spear in the horse is an oblique reference to the lance used in bullfighting. This appears unlikely. A bullfight involves the lancing of the bull, not the horse. In addition, it seems clear from the arrow-headed tip of the implement that it is a spear, not a bullfighting lance. Perhaps, however, an alternative argument in favour of the bullfight context could be mounted on the basis that Guernica represents a world turned upside down, with nothing being as it should.

30. The suggestion that the bull represented the Spanish people and the horse represented an ultimately-defeated Franco was made by Larrea (Chipp, op cit at 196). The journalist Seckler reported that Picasso told him the bull stood for darkness and brutality. Picasso also reportedly told his then-lover Francoise Gilot that horses represented the women in his life, and that he was the bull. Picasso was also the one who (rather wearily one imagines) said that the bull was just a bull and the horse was a horse. Ultimately, Picasso’s view was that “viewers are wonderfully free to make of it what they choose”: Martin, R, Picasso’s War, London: Pocket Books, 2004 at 55. He also noted that “A picture lives a life like a living creature, undergoing the changes imposed on us by our life from day to day. This is natural enough, as the picture lives only through the man [sic] who is looking at it (Chipp, op cit at 44).

31. Chipp, op cit at 58. This theme had interested Picasso for some years, and had recently appeared in the Vollard Suite (which also features images of the Minotaur, bulls and horses).

32. This was a familiar device dating back to The Three Dancers (1925). For its possible mythic significance, see note 37.

33. Picasso’s many sketches of weeping women, executed about this time, culminated in the Dora Maar inspired Weeping Woman series later in 1937.

34. It also, of course, acts more subtly to provide the central compositional triangle.

35. This ambiguity is reminiscent of the theatrical fiction of creating an exterior scene within a stage setting. It is interesting that the only comparable-sized works that Picasso had previously been involved in were his drop curtains for ballet productions such as Le 14 Juillet (Van Hensbergen, G, Guernica: The biography of a Twentieth Century Icon, New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2004 at 22). It has also been claimed that Guernica is “inconceivable” without the precedent of the drop curtains for Diaghilev (Buckley, J, Review of “Picasso and the Theatre”, The Burlington Magazine, CXLIX, April 2007 at 280). Van Hensbergen (note 18) also suggests that Picasso may have been influenced by the traditional Spanish sargas, loose canvases traditionally hung up to celebrate feasts and special holy days, or to decorate a pantheon or funerary chapel.

36. Possibly reminiscent of aspects of the Blue Period (Blunt, A, Picasso’s Guernica, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969 at 57).

37. The modernity of the electric light provides an obvious contrast to the classical allusions or myths in Picasso’s depiction of a sword-bearing warrior and a javelin transfixing the horse. Mythic origins also possibly apply to the lamp-bearer (see note 22) and the half open door, which may represent the borderline between life and death. See Hart, V, “Sigurd Lewerentz and the “Half Open Door”, Architectural History vol 39 1996 p 181.

38. Larrea claims that when Picasso asked him what a bombed town look like, Larrea answered “like a bull in a china shop” (Van Hensbergen, op cit p 33). It is true that the bull in Guernica could be seen as having a rather bemused expression, as if it is wondering why there is chaos all around it.

39. This was done at Picasso’s request..

40. Chipp, op cit Ch 6, 7; Arnheim, R, The Genesis of a Painting: Picasso’s Guernica, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973, Ch III.

41. Examples of motifs that were tried and rejected include an upright clenched fist as a vertical focus, stalks of wheat symbolic of the labour of peasants, a blinding white explosion, the use of bright colour, the use of mixed media, a Pegasus-like winged horse, a bull with an overtly human face, a red tear of blood, an overly phallic initial version of the horse’s neck, and a supposedly more overtly Christ-like pose of the warrior. Even the obvious regenerative symbol of a flower has been reduced from the bunch in Minotauromachy to the single bloom in Guernica. See Chipp, op cit at 96, 112, 116.

42. For example, the warrior assumes an extraordinary variety of positions (gender, face up/down) before Picasso is happy. The bird appears and disappears. The horse and the bull become further separated. The bull’s stance, orientation and mien alter. Chipp claims that the turning of the bull so that its tail end is on the left makes it appear more protective of the woman with the child, instead of threatening (Chipp, op cit at 123).

43. The Pavilion featured tragic photographs, art works, homages to cultural martyrs such as Gabriel Lorca, and political tracts (Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 67).

44. Later, when Franco was in full power, he sent a similar selection to the Venice Biennale in 1938 (Van Hensbergen, G, Guernica: The Biography of a Twentieth Century Icon, New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2004 at 219).

45. It also organised an exhibition in Munich that featured “degenerate” art by Jews and Bolsheviks, scattered among paintings by the inmates of a nearby mental asylum.

46. Early critics who could have been expected to have been supportive included Le Corbusier and Picasso’s journalist friend Luis Aragon. Even L’Humanite, the left wing journal, gave it only a passing reference (Martin, op cit at 118). Part of the unenthusiastic response may also have been due to the lateness of the opening of the Spanish Pavilion.

47. It is arguable that Guernica’s fame helped to educate the public into a greater acceptance that modern art may have something worthwhile to say.

48. Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 122.

49. See note 13.

50. This 1953 portrait, done from a photograph, depicted Stalin as a young man. The negative reaction to it from Soviet communists precipitated Picasso’s disillusionment with party politics. Picasso was not really cut out to be a party foot soldier. In 1948 he noted that in Russia they hated his work and loved his politics, whereas in the US the situation was reversed. Picasso commented “I’m hated everywhere. I like it that way” (van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 198).

51. Part of the reason for Franco’s denial of responsibility may have been his realisation that such an horrific event had the potential to alienate conservative and Catholic supporters, particularly overseas (Southworth, H, Guernica! Guernica! A Study of Journalism, Diplomacy, Propaganda and History, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977).

52. Franco also hated it because of its modernity.

53. Van Hensbergen, op cit at 178. For safety reasons, MoMA was Guernica’s home from about 1938 until 1981.

54. Limited references to the painting began appearing in the media. There was a 1960 exhibition of Picasso works in Barcelona, and the Picasso Museum opened there in 1963.

55. The right wing mouthpiece journal Alcazar had reproduced the painting for the first time, describing it as part of the cultural patrimony of the Spanish people, and arguing that it should be on exhibition in Spain “as proof of the definitive end of the contrasts and differences aroused by the last civil conflict” (van Hensbergen, op cit at 258). This dalliance with modernity upset sections of the extreme right. A 1971 exhibition of Picasso’s Vollard Suite was smashed up by “warriors” of Christ the King, who considered that Franco’s flirtation with Guernica symbolised the regime’s decadence and loss of direction (Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 269).

56. Strictly speaking it was not a return, as Guernica had previously never been in Spain.

57. Van Hensbergen, op cit note 35 at 297.