Art and Survival in Patagonia

how destroyed Patagonian Indian cultures live on through their art

introduction

If you travel to Argentina, it is difficult not to be struck by its violent and turbulent past, and by the way in which echoes of this continue to reverberate right through to the present day. Countless statues, monuments, plazas and street names are all potent visual reminders of the heroes and victims of its war of independence, its civil wars, its military coups, the mass political murders of people (“the Disappeared”), the disputes with neighbouring Chile, and the continuing pain of the disastrous Malvinas (Falklands) War.

There is one issue, however, that has been embraced only in relatively recent times, resulting in a painful re-evaluation, by some, of a previously cherished and rosy view of the past. This issue is the contentious treatment of the original inhabitants of the Patagonian south of the country. In this article, we’ll examine this long neglected story, and uncover some remarkable artistic survivors of what was an extraordinarily conflicted period.

First, though, for those who may need it, a potted geography lesson. Patagonia, the setting of our story, is not a country, but a large region, three times the size of Germany. It straddles the border between Argentina and Chile at the southern tip of South America. It is the land of the Magellan Channel, Tierra del Fuego and Cape Horn. Physically. it ranges from extremely wet to extremely dry, from vast plains to forests to glaciers and mountain ranges. Befitting its position at “the uttermost part of the Earth”[1], its weather can be extreme, variable and unpredictable. Mild conditions can quickly turn to freezing cold, heavy rain and intense wind. Particularly in the south, Patagonia can be a very challenging place to be.

There is one issue, however, that has been embraced only in relatively recent times, resulting in a painful re-evaluation, by some, of a previously cherished and rosy view of the past. This issue is the contentious treatment of the original inhabitants of the Patagonian south of the country. In this article, we’ll examine this long neglected story, and uncover some remarkable artistic survivors of what was an extraordinarily conflicted period.

First, though, for those who may need it, a potted geography lesson. Patagonia, the setting of our story, is not a country, but a large region, three times the size of Germany. It straddles the border between Argentina and Chile at the southern tip of South America. It is the land of the Magellan Channel, Tierra del Fuego and Cape Horn. Physically. it ranges from extremely wet to extremely dry, from vast plains to forests to glaciers and mountain ranges. Befitting its position at “the uttermost part of the Earth”[1], its weather can be extreme, variable and unpredictable. Mild conditions can quickly turn to freezing cold, heavy rain and intense wind. Particularly in the south, Patagonia can be a very challenging place to be.

Part i: the people

Conflicts on the colonial borders

Due to its remoteness and its difficult climate, Patagonia was the last major continental land mass to be inhabited by humans, probably starting about 10-12,000 years ago [2]. Indeed, it was largely ignored by both Chile and Argentina until the 1840s, when serious attempts to colonise the area began [3]. In many cases, this gave rise to conflicts with the native Indians who, at the time, probably numbered about 10,000–11,000, and were scattered over the whole vast area. This development would prove to have tragic and long-lasting consequences [4].

Conflicts arose from a number of factors. Disagreements could easily result, for example, from cultural differences that were not fully appreciated by either side. So, for example, the Indians had no developed sense of private property; this was interpreted by the eccentric adventurer Julius Popper as revealing “their alarming communist tendencies. It was useless to explain to them that the horses and sheep, being the property of the company, should not have been taken. The [Selk’nam] do not understand political economy…” [5]. Other disagreements stemmed from the unchecked spread of sheep and cattle ranchers over “unclaimed” territories previously occupied by Indians; the intrusion of apparently-lawless whalers and sealers in the south; the outbreak of devastating new diseases against which the Indians had no natural protection; and forced relocations of Indians away from their traditional lands.

There was also considerable outright violence. This took various forms. Gold miners, for example, forcibly took or kidnapped Indian women. Some ranchers killed Indians, often on the basis that they had taken their livestock or had behaved “aggressively”. It is often said that they also offered money rewards for each Indian head or pair of ears, though the evidence that this was a widespread practice is not strong [6].

It does seem clear that some armed bands actively hunted Indians. The main culprit here was evidently Julius Popper himself, who is reputed to have accompanied his own private armed force in organised raids against the Selk’nam in Tierra del Fuego (Fig 1). The scale of Popper’s activities has, however, been disputed. Canclini, for example, suggests that although Popper was certainly involved in killing, this reputation was promoted and possibly inflated by Popper himself as a senseless piece of bravado prompted by his own megalomania [7]. Canclini also suggests that the often-reproduced photograph in Fig 1 was posed as part of Popper’s self-promotion [8].

Conflicts arose from a number of factors. Disagreements could easily result, for example, from cultural differences that were not fully appreciated by either side. So, for example, the Indians had no developed sense of private property; this was interpreted by the eccentric adventurer Julius Popper as revealing “their alarming communist tendencies. It was useless to explain to them that the horses and sheep, being the property of the company, should not have been taken. The [Selk’nam] do not understand political economy…” [5]. Other disagreements stemmed from the unchecked spread of sheep and cattle ranchers over “unclaimed” territories previously occupied by Indians; the intrusion of apparently-lawless whalers and sealers in the south; the outbreak of devastating new diseases against which the Indians had no natural protection; and forced relocations of Indians away from their traditional lands.

There was also considerable outright violence. This took various forms. Gold miners, for example, forcibly took or kidnapped Indian women. Some ranchers killed Indians, often on the basis that they had taken their livestock or had behaved “aggressively”. It is often said that they also offered money rewards for each Indian head or pair of ears, though the evidence that this was a widespread practice is not strong [6].

It does seem clear that some armed bands actively hunted Indians. The main culprit here was evidently Julius Popper himself, who is reputed to have accompanied his own private armed force in organised raids against the Selk’nam in Tierra del Fuego (Fig 1). The scale of Popper’s activities has, however, been disputed. Canclini, for example, suggests that although Popper was certainly involved in killing, this reputation was promoted and possibly inflated by Popper himself as a senseless piece of bravado prompted by his own megalomania [7]. Canclini also suggests that the often-reproduced photograph in Fig 1 was posed as part of Popper’s self-promotion [8].

The violence against Indians reached a crescendo in the form of concerted mass military action by the Argentine government – the so-called “Conquest of the Desert” [9]. This was a merciless 1878-79 campaign led by General Julio Roca. Its aim was to “free up” the prime asset of some 8 million hectares of land in northern Patagonia for settlement and development, and to remove the perceived threat from Chile, which had been seeking to expand its interests (Fig 2).

The campaign explicitly involved the eradication of Indians, including the northern Tehuelche [10], who were occupying the area north of the Rio Negro, and who had been mounting increasingly violent and costly raids [11]. Given Roca’s overwhelming superiority in both numbers and weaponry, the campaign led to a one-sided and crushing victory, with over a thousand Indians killed outright and many thousands more taken prisoner.

A march to extinction

The combined effect of all these developments was that a number of Indian cultural/racial groups were virtually wiped out, or lost their cultural identity. In Tierra del Fuego, for example, the territory of the hunting and gathering Selk’nam [12], where “homicidal violence was the rule” [13], the result was that by the early 20th century the Selk’nam had been “virtually eliminated from their ancestral home. Those who managed to elude death or relocation scattered in the forests” [14]. Further north, a viral epidemic, expulsions and relocations of the Southern Tehuelche [15] marked the “beginning of cultural mutations and their march towards extinction” [16]. Further north still, the already depleted number of northern Tehuelche who survived Roca’s campaign were effectively culturally destroyed as a group, either by being sent to special reservations or apportioned out as servants or labourers, in effect being reduced from hunters and gatherers to peasants [17].

The damage done, both physical and cultural, was devastatingly comprehensive. But, remarkably, there are two extraordinary types of Indian artistic image that have survived, becoming almost iconic in their power to evoke past lives, and achieving even more power from the tragic fate of their subjects or creators. It is to these images that we now turn.

The damage done, both physical and cultural, was devastatingly comprehensive. But, remarkably, there are two extraordinary types of Indian artistic image that have survived, becoming almost iconic in their power to evoke past lives, and achieving even more power from the tragic fate of their subjects or creators. It is to these images that we now turn.

part 2: the images

the Tehuelches and the cave of hands

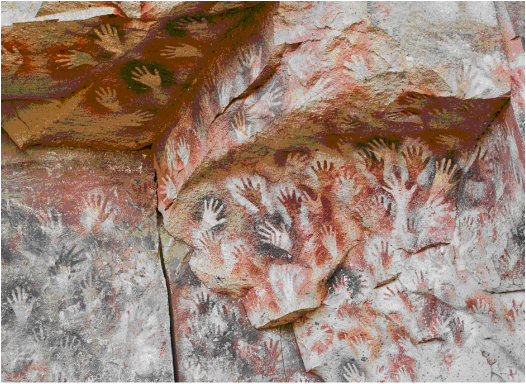

Ancient rock art, which occurs in many places in the world, has been described as “one of the major cultural riches of humankind”. It is often “the only concrete intelligible expression and testimony of the complexity of the thoughts, beliefs and cults of lost indigenous civilisations” [18]. One particularly fine example can be found in a spectacular but remote canyon in central Patagonia (Fig 3) [19]. This is the Cueva de las Manos – “The Cave of Hands” – an exceptional collection of rock art which entered the UNESCO world heritage list in 1991[20].

Barely known to the outside world before the 1950s, but now increasingly a tourist destination, the site is dramatically positioned half way up the walls of the canyon, 90 metres above the level of the Pinturas River.

The artworks cover a stunning 8,000+ years of artistic achievement, and are spread over one large cave and hundreds of metres of rock faces [21]. This site is said to be unique in the world for its age and its continuity through time [22]. As the UNESCO Evaluation states, “It is believed to have been the work of the historic Tehuelche hunter-gatherers who were inhabiting the vast area of Patagonia when the first Spanish traders and settlers arrived”[23]. These were the ancestors of the same people whom would later be ravaged by Roca’s forces.

Both the size of the site, and the amount of art that has accumulated over the millennia, is impressive. The entrance to the main cave is about 50 feet wide and 33 feet high, and the cave stretches back about 80 feet, with the height reducing to about 6 feet. The entrance is screened by a rock wall covered with stencilled outlines of human hands. Inside, the are hundreds more multi-coloured hand stencils. But there are also countless skilled depictions of animals and hunting scenes, showing animals and human figures interacting in a dynamic and naturalistic manner [24].

The artworks cover a stunning 8,000+ years of artistic achievement, and are spread over one large cave and hundreds of metres of rock faces [21]. This site is said to be unique in the world for its age and its continuity through time [22]. As the UNESCO Evaluation states, “It is believed to have been the work of the historic Tehuelche hunter-gatherers who were inhabiting the vast area of Patagonia when the first Spanish traders and settlers arrived”[23]. These were the ancestors of the same people whom would later be ravaged by Roca’s forces.

Both the size of the site, and the amount of art that has accumulated over the millennia, is impressive. The entrance to the main cave is about 50 feet wide and 33 feet high, and the cave stretches back about 80 feet, with the height reducing to about 6 feet. The entrance is screened by a rock wall covered with stencilled outlines of human hands. Inside, the are hundreds more multi-coloured hand stencils. But there are also countless skilled depictions of animals and hunting scenes, showing animals and human figures interacting in a dynamic and naturalistic manner [24].

Fig 4: Cave of Hands, hunting scenes, hand stencils (© Michael Turtle, 2012, http://www.timetravelturtle.com/2012/03/cave-hands-patagonia-argentina/. Reproduced with permission.

Archaeologists have identified three main stylistic groups at the site. The first in time, probably starting about 9,500 years ago, features hunting scenes, typically involving guanacos (a variety of small camelids, still commonly found in Patagonia), or rheas (similar to small ostriches) (Fig 4). A variety of hunting techniques are shown – groups of hunters surrounding the animal, using ambushes or attacking with bolas, a throwing weapon with stones on the ends of interconnected cords.

Archaeologists have identified three main stylistic groups at the site. The first in time, probably starting about 9,500 years ago, features hunting scenes, typically involving guanacos (a variety of small camelids, still commonly found in Patagonia), or rheas (similar to small ostriches) (Fig 4). A variety of hunting techniques are shown – groups of hunters surrounding the animal, using ambushes or attacking with bolas, a throwing weapon with stones on the ends of interconnected cords.

Fig 5: Cave of Hands, hand stencils (© Michael Turtle, 2012,

http://www.timetravelturtle.com/2012/03/cave-hands-patagonia-argentina/ . Reproduced with permission

The second group, dating from about 7,000 years ago, features stencils of human hands, often superimposed on earlier ones, and occasional stencils of ostrich feet. These are a particularly intimate link to the ancient artists (Fig 5) [25]. The third group, from as recently as 1,300 years ago up to the date of their last habitation 700 years ago, consists of bright red abstract geometric figures and schematic depictions of animals and humans.

http://www.timetravelturtle.com/2012/03/cave-hands-patagonia-argentina/ . Reproduced with permission

The second group, dating from about 7,000 years ago, features stencils of human hands, often superimposed on earlier ones, and occasional stencils of ostrich feet. These are a particularly intimate link to the ancient artists (Fig 5) [25]. The third group, from as recently as 1,300 years ago up to the date of their last habitation 700 years ago, consists of bright red abstract geometric figures and schematic depictions of animals and humans.

Fig 6: Cave of Hands, reptiles with superimposed hand (© Michael Turtle, 2012, http://www.timetravelturtle.com/2012/03/cave-hands-patagonia-argentina/. Reproduced with permission.

The pigments used are derived from natural minerals which had been ground and mixed with a binder. Red and purple pigments came from iron oxide, white from kaolin, yellow from natrojarosite, and black from manganese oxide. For the stencils, the artist presumably blew the mixture, probably using pipes made of bone, against a hand outstretched on the rock face. It appears that most depictions involve left hands, which suggests that the maker was right handed (assuming that the artists were stencilling their own hands).

Male hands can generally be distinguished from female by their bigger overall size, though to distinguish adolescent males from females may require an examination of finger ratios -- for example, the length of the ring fingers of females relative to their index fingers tends to be higher for females than it is for males [26]. Due to the low humidity, the stability of the rock, the protection from infiltration by water, and evidence of ancient retouching, the art is in an excellent state of preservation, despite its age.

The concentration of paintings on the site contrasts sharply with their lack in immediately adjoining regions which feature similar rock shelters and caves. It has been suggested [27] that this indicates that this site had particular cultural or personal significance to the local peoples, and the fact that many of the hand stencils are overlapped on earlier ones suggests that this was a persistent and long tradition. Exactly what that significance was – whether it related to Tehuelche concepts of territoriality, ownership, identity, aesthetics or spirituality – is a matter of speculation. The Cave of Hands, however, will always remain part of their ancient artistic heritage.

The pigments used are derived from natural minerals which had been ground and mixed with a binder. Red and purple pigments came from iron oxide, white from kaolin, yellow from natrojarosite, and black from manganese oxide. For the stencils, the artist presumably blew the mixture, probably using pipes made of bone, against a hand outstretched on the rock face. It appears that most depictions involve left hands, which suggests that the maker was right handed (assuming that the artists were stencilling their own hands).

Male hands can generally be distinguished from female by their bigger overall size, though to distinguish adolescent males from females may require an examination of finger ratios -- for example, the length of the ring fingers of females relative to their index fingers tends to be higher for females than it is for males [26]. Due to the low humidity, the stability of the rock, the protection from infiltration by water, and evidence of ancient retouching, the art is in an excellent state of preservation, despite its age.

The concentration of paintings on the site contrasts sharply with their lack in immediately adjoining regions which feature similar rock shelters and caves. It has been suggested [27] that this indicates that this site had particular cultural or personal significance to the local peoples, and the fact that many of the hand stencils are overlapped on earlier ones suggests that this was a persistent and long tradition. Exactly what that significance was – whether it related to Tehuelche concepts of territoriality, ownership, identity, aesthetics or spirituality – is a matter of speculation. The Cave of Hands, however, will always remain part of their ancient artistic heritage.

The body art of the Fuegian selk'nam Indians

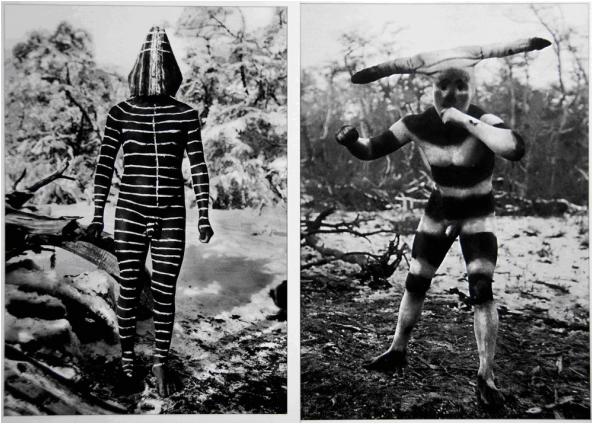

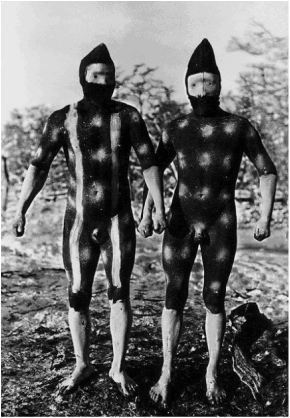

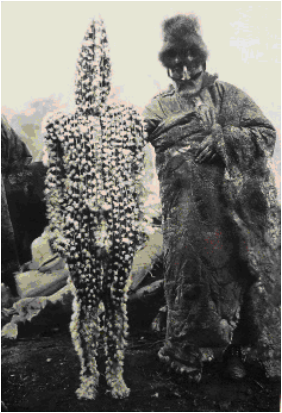

The Cave of Hands offers a tangible link with past lives, a link which is particularly direct and personal in the case of the stencils which reflect the actual hands of their ancient creators. Another group of indigenous images that have survived are also direct and personal, though in quite a different way – these photographic images are of actual people themselves (Figs 7, 8).

The subjects of these striking images are the Selk’nam people, who lived in Tierra del Fuego for some 6,000 years, until their forced disintegration in relatively recent times [28]. For the Selk’nam, hunting provided their main source of sustenance, clothing and shelter. This was an exclusively male occupation, as was tool-making, another essential task. This male dominance in the Selk’nam was expressed through an elaborate initiation ceremony known as the Hain [29]. This ceremony, last recorded in 1923, was the most important event in the Selk’nam culture Apart from confirming the patriarchal nature of their society, and initiating young boys into full manhood, the ceremony also served as an occasion for periodic gatherings of the clan who otherwise might have little contact with each other.

Each ceremony lasted an extraordinarily long time – it could go on for months, depending partly on how long the food supply in the locality lasted. The components of the ceremony were carried out according to an order which could be varied according to circumstances. It involved tests for courage, resourcefulness, resisting temptation, resisting pain and overcoming fear; highly-charged and dramatic re-enactments of mythic events; and prolonged instructional courses to train the young men in the tasks for which they would be responsible.

Each of the exclusively-male participants in the ceremony had their own pattern of decoration, which varied according to their role. These patterns were therefore highly significant, and were prescribed in detail, with unauthorised or inappropriate patterns being strictly monitored. The patterns could appear both on the particpants’ bodies and on the masks or conical hats of bark or guanaco skin which many of them wore.

In each case, the nature of a participant’s decoration was determined by the “sky” that he represented [30]. These skies were central elements in Selk’nam mythology. In broad terms, they comprised the various directions, or points of the compass. According to Canclini, the north sky was associated with the sea and rain; the south with wind, snow and moon; the east was the pre-eminent sky from which the sun rose; and the west was where the sun went [31]. Each of these was also associated with particular territories and mythological figures. The relevant sky could also have a role in determining the colour of the patterns – red for the west, white for the south, and black for the north [32].

A major role was played by malevolent spirits, known as shoorts (Fig 9) whose role was to frighten the initiates, and to intimidate women and remind them of their subordinate role in society. The shoorts were represented by distinctively decorated, muscular men, painted from head to foot, often in colours of red and white. Boys undergoing initiation were also decorated at various stages in distinctive ways, including for the climactic scene where one specially-chosen, feather-adorned initiate was presented in the form of a newborn child (Fig 10).

Each ceremony lasted an extraordinarily long time – it could go on for months, depending partly on how long the food supply in the locality lasted. The components of the ceremony were carried out according to an order which could be varied according to circumstances. It involved tests for courage, resourcefulness, resisting temptation, resisting pain and overcoming fear; highly-charged and dramatic re-enactments of mythic events; and prolonged instructional courses to train the young men in the tasks for which they would be responsible.

Each of the exclusively-male participants in the ceremony had their own pattern of decoration, which varied according to their role. These patterns were therefore highly significant, and were prescribed in detail, with unauthorised or inappropriate patterns being strictly monitored. The patterns could appear both on the particpants’ bodies and on the masks or conical hats of bark or guanaco skin which many of them wore.

In each case, the nature of a participant’s decoration was determined by the “sky” that he represented [30]. These skies were central elements in Selk’nam mythology. In broad terms, they comprised the various directions, or points of the compass. According to Canclini, the north sky was associated with the sea and rain; the south with wind, snow and moon; the east was the pre-eminent sky from which the sun rose; and the west was where the sun went [31]. Each of these was also associated with particular territories and mythological figures. The relevant sky could also have a role in determining the colour of the patterns – red for the west, white for the south, and black for the north [32].

A major role was played by malevolent spirits, known as shoorts (Fig 9) whose role was to frighten the initiates, and to intimidate women and remind them of their subordinate role in society. The shoorts were represented by distinctively decorated, muscular men, painted from head to foot, often in colours of red and white. Boys undergoing initiation were also decorated at various stages in distinctive ways, including for the climactic scene where one specially-chosen, feather-adorned initiate was presented in the form of a newborn child (Fig 10).

It is sobering to reflect that the cultural richness reflected in these ceremonies, which evolved over centuries and possibly millennia, was totally extinguished within a few decades of intensive European contact. Despite that, we can be grateful that these photographic images – reproduced in countless postcards throughout Patagonia and recently being exhibited in Europe [33] – continue to survive as reminders of that richness, and of the fate of the participants whose unique cultural identity would otherwise be lost.

Julio roca and The re-evaluation of a hero

Ironically, while the cave and body art of the Patagonian Indians has become increasingly intriguing to modern viewers, the reputation of Julio Roca, the architect of the Conquest of the Desert, appears to have suffered a corresponding decline from its high point in 1880. Back then, fresh from his military victory, Roca had quickly taken over the presidency of Argentina and proceeded to lead the country into an era of rapid economic growth [34]. His perceived status as a national hero and patriot was reflected in statues and street names across the country and his statesmanlike image appeared on the front of the 100 peso banknote, together with a painting of his armed raiders reproduced on the reverse (Fig 2). Another depiction showing the Indians as bloodthirsty killers, church looters and women-snatchers (Fig 9A), thus justifying the government's campaign, was hailed as "Argentina's first genuinely national work of art" when it was first exhibited in 1892 [34A].

But, as time has passed, some Argentines, including Indigenous groups, have begun to reconsider Roca’s activities in an increasingly harsh light, with some claiming that he should instead be regarded as a corrupt and genocidal murderer [35]. It has been reported that these moves have already resulted in some street names being altered and statues being daubed with anti-Roca slogans, while an outspoken Roca apologist who rejected the genocide claims was, reportedly, forced to resign as director of the Argentine National Historical Museum [36].

Equally significantly, however, Roca’s image on the Argentine 100 peso note is now being replaced by that of Eva Peron. While this change was originally intended simply as a one-off commemorative issue, the Argentine President has announced that the Peron version is to become the sole new official note, effective from 2015 [37]. How far some attitudes may be changing can also be gauged by the frank admission on a government website that Roca was “the mastermind of the largest massacre of Patagonia’s native population” [38].

The continuing survival of the Indian images that we have discussed, contrasting so sharply with what seems to be a gradual fading of Roca from the public face of approved Argentine history, is a potent demonstration, if one were needed, of the importance of images in society.

Equally significantly, however, Roca’s image on the Argentine 100 peso note is now being replaced by that of Eva Peron. While this change was originally intended simply as a one-off commemorative issue, the Argentine President has announced that the Peron version is to become the sole new official note, effective from 2015 [37]. How far some attitudes may be changing can also be gauged by the frank admission on a government website that Roca was “the mastermind of the largest massacre of Patagonia’s native population” [38].

The continuing survival of the Indian images that we have discussed, contrasting so sharply with what seems to be a gradual fading of Roca from the public face of approved Argentine history, is a potent demonstration, if one were needed, of the importance of images in society.

End Notes

[1] This description is taken from E Lucas Bridges’ book Uttermost Part of the Earth (1948).

[2] Luis Alberto Borrero and Colin McEwan, “The Peopling of Patagonia”, in Patagonia: Natural history, prehistory and ethnography at the uttermost end of the world, ed Colin McEwan, Luis A Borrero and Alfredo Prieto, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1997, at 32 onwards.

[3] There had of course been much earlier sporadic encounters with explorers, adventurers and traders: see Arnoldo Canclini, The Fuegian Indians: their life, habits and history, Continente, Buenas Aires, 2012, at 46.

[4] Mateo Martinic B, “The Meeting of Two Cultures” in McEwan, op cit at 110.

[5] Quoted in Maria Laura Borla and Marisol Vereda, Exploring Tierra del Fuego, Editorial Utopias, Ushuaia, 2005, at 102-3.

[6] Canclini, op cit at 118.

[7] Canclini, op cit at 116-7.

[8] Canclini, op cit at 117.

[9] In the original Spanish, La Conquiesta del Desierto. “Desert” is understood not in the sense of being a sandy waste, but rather as a deserted area. (The presence of Indians evidently did not count in this respect.) Perhaps a more apt name would be the Conquest of the Wilderness: see, for example, David Rock, Argentina, 1516-1987: From Spanish colonization to Alfonsin, University of California Press, 1987, at 154. Additional military campaigns against the Indians were conducted until 1884.

[10] Based on early explorers and travellers’ tales, the Tehuelche achieved a mythical reputation as being physical giants: see Jean-Paul Duviols, “The Patagonian ‘Giants’”, in McEwan, op cit at 127. Stories that they left enormous footprints were probably based on the prints left by their guanaco leather boots. For discussion of the apparently mistaken belief that the word “patagon” actually means “bigfoot” see Duviols at 129 onwards.

[11] Jill Hedges, Argentina: A Modern History, I B Taurus, 2011, at 22; Canclini, op cit at 115 onwards. One raid in particular, in 1876, is reported to have involved taking huge numbers of cattle and numerous “white” captives.

[12] Also known as the Ona.

[13] Mateo, op cit at 121.

[14] Mateo, op cit at 122. In contrast, the “canoe tribe”, the maritime Yámana, fared considerably better, partly as a result of the work of some exceptional missionaries. It was from this tribe that Captain Fitzroy from the Beagle famously “adopted” Jemmy Button, Fuegia Basket and York Minster, and took them to England. For a full account, including the return to Tierra del Fuego and later exploits, see Nick Hazlewood, Savage: survival, revenge and the theory of evolution, Sceptre, London, 2000.

[15] Also known as the Aónikenk.

[16] Mateo, op cit at 117.

[17] Hedges, op cit at 22.

[18] Jean Clottes, “Rock Art: An Endangered Heritage Worldwide”, Journal of Anthropological Research. Vol 64, No 1 2008 p1-18, at 1.

[19] More specifically, it is in the northwest of the province of Santa Cruz. The nearest town is Perito Moreno.

[20] Other UNESCO listed sites in Argentina include the Los Glaciares and Iguazu National Parks.

[21] For a detailed bibliography for the site, see http://cuevadelasmanos.org/publicaciones.html

[22] UNESCO Evaluation Report “Cueva de las Manos, Rio Pinturas”, http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/936.

[23] UNESCO Evaluation Report, op cit.

[24] UNESCO Evaluation Report, op cit.

[25] Even in modern times, the image of a hand or fist is a common symbol of solidarity; see George Nash, “A history of handy work”, Minerva, 23(6) Nov/Dec 2012, at 261.

[26] Dean Snow, “Sexual Dimorphism in European Upper Paleolithic Cave Art”, American Antiquity, vol 78(4), 2013, p 746.

[27] Maria Mercedes Podesta, “The Cave of Hands as an example of cultural-natural hybrid heritage”, in Nature and Culture, German Commission for UNESCO, Brandenburg, 2007 at 119 onwards.

[28] These photographs are the work of the Austrian priest/ethnologist Martin Gusinde, who attended the last recorded Hain in 1923: see Exhibition Catalogue, “Patagonie: Images du bout du monde”, Musėe du quai Branly, 2012.

[29] In discussing this ceremony I have relied on Ann Chapman, “The Great Ceremonies of the Selk’nam and the Yámana”, in McEwan, op cit at 82; and Canclini, op cit at 110 onwards.

[30] The various skies were also represented by special posts in the large hut which formed the central area for the ceremony.

[31] Canclini, op cit at 102.

[32] The decorations also served to hide the participants’ actual identity, adding verisimilitude to their transformations into other-worldly beings.

[33] See Exhibition Catalogue, “Patagonie: Images du bout du monde”, Musėe du quai Branly, 2012.

[34] He returned to the presidency in 1897.

[34A] Laura Malosetti Costa, "The Return of the Indian Raid", Collection Highlights, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, https://www.bellasartes.gob.ar/en/the-collection-highlights/6297

[35] Rory Carroll, “Argentinian founding father recast as genocidal murderer”, The Guardian, 13 January 2011.

[36] “Genocidio en las Pampas” http://argentina.indymedia.org/news/2005/02/264061.php

[37] “Evita Peron 100 Pesos bill to commemorate 60th anniversary of her death”, 26 July 2012 http://en.mercopress.com/2012/07/26/evita-peron-100-pesos-bill-to-commemorate-60th-anniversary-of-her-death

[38] Embassy of the Argentine Republic, London, www.argentine-embassy-uk.org (accessed 16 April 2014).

© Philip McCouat 2014

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Art and Survival in Patagonia", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

[2] Luis Alberto Borrero and Colin McEwan, “The Peopling of Patagonia”, in Patagonia: Natural history, prehistory and ethnography at the uttermost end of the world, ed Colin McEwan, Luis A Borrero and Alfredo Prieto, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1997, at 32 onwards.

[3] There had of course been much earlier sporadic encounters with explorers, adventurers and traders: see Arnoldo Canclini, The Fuegian Indians: their life, habits and history, Continente, Buenas Aires, 2012, at 46.

[4] Mateo Martinic B, “The Meeting of Two Cultures” in McEwan, op cit at 110.

[5] Quoted in Maria Laura Borla and Marisol Vereda, Exploring Tierra del Fuego, Editorial Utopias, Ushuaia, 2005, at 102-3.

[6] Canclini, op cit at 118.

[7] Canclini, op cit at 116-7.

[8] Canclini, op cit at 117.

[9] In the original Spanish, La Conquiesta del Desierto. “Desert” is understood not in the sense of being a sandy waste, but rather as a deserted area. (The presence of Indians evidently did not count in this respect.) Perhaps a more apt name would be the Conquest of the Wilderness: see, for example, David Rock, Argentina, 1516-1987: From Spanish colonization to Alfonsin, University of California Press, 1987, at 154. Additional military campaigns against the Indians were conducted until 1884.

[10] Based on early explorers and travellers’ tales, the Tehuelche achieved a mythical reputation as being physical giants: see Jean-Paul Duviols, “The Patagonian ‘Giants’”, in McEwan, op cit at 127. Stories that they left enormous footprints were probably based on the prints left by their guanaco leather boots. For discussion of the apparently mistaken belief that the word “patagon” actually means “bigfoot” see Duviols at 129 onwards.

[11] Jill Hedges, Argentina: A Modern History, I B Taurus, 2011, at 22; Canclini, op cit at 115 onwards. One raid in particular, in 1876, is reported to have involved taking huge numbers of cattle and numerous “white” captives.

[12] Also known as the Ona.

[13] Mateo, op cit at 121.

[14] Mateo, op cit at 122. In contrast, the “canoe tribe”, the maritime Yámana, fared considerably better, partly as a result of the work of some exceptional missionaries. It was from this tribe that Captain Fitzroy from the Beagle famously “adopted” Jemmy Button, Fuegia Basket and York Minster, and took them to England. For a full account, including the return to Tierra del Fuego and later exploits, see Nick Hazlewood, Savage: survival, revenge and the theory of evolution, Sceptre, London, 2000.

[15] Also known as the Aónikenk.

[16] Mateo, op cit at 117.

[17] Hedges, op cit at 22.

[18] Jean Clottes, “Rock Art: An Endangered Heritage Worldwide”, Journal of Anthropological Research. Vol 64, No 1 2008 p1-18, at 1.

[19] More specifically, it is in the northwest of the province of Santa Cruz. The nearest town is Perito Moreno.

[20] Other UNESCO listed sites in Argentina include the Los Glaciares and Iguazu National Parks.

[21] For a detailed bibliography for the site, see http://cuevadelasmanos.org/publicaciones.html

[22] UNESCO Evaluation Report “Cueva de las Manos, Rio Pinturas”, http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/936.

[23] UNESCO Evaluation Report, op cit.

[24] UNESCO Evaluation Report, op cit.

[25] Even in modern times, the image of a hand or fist is a common symbol of solidarity; see George Nash, “A history of handy work”, Minerva, 23(6) Nov/Dec 2012, at 261.

[26] Dean Snow, “Sexual Dimorphism in European Upper Paleolithic Cave Art”, American Antiquity, vol 78(4), 2013, p 746.

[27] Maria Mercedes Podesta, “The Cave of Hands as an example of cultural-natural hybrid heritage”, in Nature and Culture, German Commission for UNESCO, Brandenburg, 2007 at 119 onwards.

[28] These photographs are the work of the Austrian priest/ethnologist Martin Gusinde, who attended the last recorded Hain in 1923: see Exhibition Catalogue, “Patagonie: Images du bout du monde”, Musėe du quai Branly, 2012.

[29] In discussing this ceremony I have relied on Ann Chapman, “The Great Ceremonies of the Selk’nam and the Yámana”, in McEwan, op cit at 82; and Canclini, op cit at 110 onwards.

[30] The various skies were also represented by special posts in the large hut which formed the central area for the ceremony.

[31] Canclini, op cit at 102.

[32] The decorations also served to hide the participants’ actual identity, adding verisimilitude to their transformations into other-worldly beings.

[33] See Exhibition Catalogue, “Patagonie: Images du bout du monde”, Musėe du quai Branly, 2012.

[34] He returned to the presidency in 1897.

[34A] Laura Malosetti Costa, "The Return of the Indian Raid", Collection Highlights, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, https://www.bellasartes.gob.ar/en/the-collection-highlights/6297

[35] Rory Carroll, “Argentinian founding father recast as genocidal murderer”, The Guardian, 13 January 2011.

[36] “Genocidio en las Pampas” http://argentina.indymedia.org/news/2005/02/264061.php

[37] “Evita Peron 100 Pesos bill to commemorate 60th anniversary of her death”, 26 July 2012 http://en.mercopress.com/2012/07/26/evita-peron-100-pesos-bill-to-commemorate-60th-anniversary-of-her-death

[38] Embassy of the Argentine Republic, London, www.argentine-embassy-uk.org (accessed 16 April 2014).

© Philip McCouat 2014

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Art and Survival in Patagonia", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME