Titian, Prudence and the three-headed beast

By Philip McCouat

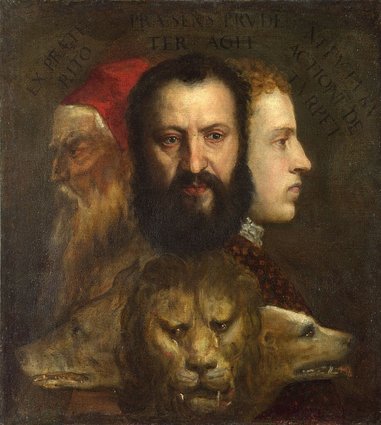

On any view, the Allegory of Prudence, traditionally attributed to the Venetian artist Titian [1], is a strange painting. It depicts the heads of an old man in left profile, an adult facing the viewer and a youth in right profile, with corresponding images below them representing the heads of a wolf, a lion and a dog. Above and behind them all is a Latin inscription – almost invisible in most reproductions – with the words ex praete/rito above the old man, praesens prvden/ter agit above the middle man and ni fvtvrv/actione de/tvrpet above the youngest. The full inscription can be translated as “from the past /the present acts prudently/lest it spoil future action” [2].

On any view, the Allegory of Prudence, traditionally attributed to the Venetian artist Titian [1], is a strange painting. It depicts the heads of an old man in left profile, an adult facing the viewer and a youth in right profile, with corresponding images below them representing the heads of a wolf, a lion and a dog. Above and behind them all is a Latin inscription – almost invisible in most reproductions – with the words ex praete/rito above the old man, praesens prvden/ter agit above the middle man and ni fvtvrv/actione de/tvrpet above the youngest. The full inscription can be translated as “from the past /the present acts prudently/lest it spoil future action” [2].

Although it was probably painted over a period round 1560, the painting was not included in an inventory of Titian’s works on his death, and apparently did not receive any mention at all until decades later, in 1740 [3]. Possibly for this reason, there has been considerable controversy about its correct interpretation, and about what the artist was intending to convey.

Is iT about politics?

Originally, the painting was interpreted as a political allegory [4], reflecting the dilemma of Alfonso I d’Este, the duke of Ferrara, who, in common with other Italian princes, had to decide whether to support the Emperor Charles V or Pope Julius II. Writing in 1756, Pierre Remy suggested that the lion could represent the duke’s courage, the wolf stood for the pope’s rapacity and the dog represented commitment and loyalty [5]. It appears that political allegories such as this were common in Italian Renaissance paintings, with animals often being used to represent the great European powers. But, as Sheila Hale points out [6], this particular interpretation really did not work, as Julius had died before Charles even became emperor. A later change in the interpretation from Julius II to Julius III did not work either, as Alfonso had died by then. Furthermore, none of these political interpretations explained the inscription, which clearly indicated some connection to do with time [7].

is it about the three ages of man?

Much later, in 1924, Baron von Haldeln reported on this “little-known work”, commenting that the inscription made it clear that the painting represents the “Three Ages of Man” [8]. The Baron suggested that the wolf possibly represented the subtlety of old age, with the lion as the vigour of manhood and the dog as the frivolity of youth. However, given that Titian had already done a “wonderfully bucolic” idyll of the Three Ages (Fig 2), the Baron wondered why he would revisit the subject in such an odd way. Why, he asked, would Titian resort in his old age to a work of such “extremely condensed and epigrammatic brevity” which resembled a severe heraldic shield more than a painting? This was especially strange because there was nothing else by Titian that was analogous to this arrangement of disembodied heads of men and animals. Von Hadeln, clearly having some reservations about the work, concluded that it was probably best explained not as a picture, but as “timpano” -- a painted cover which was intended to protect an actual picture from dust and injury, something that Titian was known to do.

Like Remy’s suggestion, however, the Baron’s interpretation did not really explain the inscription. The “Three Ages” concept was normally associated with ideas of the transience of beauty or of life itself, but the inscription clearly seems to suggest something different or wider than that.

is it about prudence and time?

The first comprehensive interpretation – still widely accepted today – was put forward just two years later. Panofsky and Saxl argued that the painting actually expressed at least three levels of meaning. Beyond the straightforward Three Ages concept, it also expressed the second, wider concept of Time itself, as having a past (represented by the old man looking back), a present (the man looking directly at the viewer) and a future (represented by the youth looking forward). Thirdly, as encapsulated by the inscription, it expressed the related concept of Prudence, which combined memory (to remember the past), intelligence (to draw lessons in the present) and foresight (to use these lessons to anticipate wise action in the future) [9].

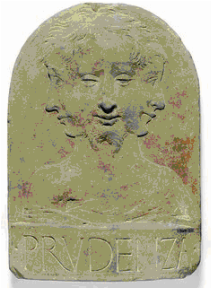

Panofsky and Saxl supported this multi-layered solution by drawing on two previously-unrelated traditions. The first of these was the traditional depiction of Prudence as having three heads or faces (Fig 3). The second tradition, which explained the presence of the animal heads, was traced back to a creature which accompanied the Hellenistic Egyptian god Serapis. This creature had the heads of a wolf, lion and dog (Fig 4). At least since the fifth century [10]. this three-headed creature has been regarded as an embodiment of Time, with the voracious wolf representing the past which devours the memory of all things, the vigorous lion representing the present and the dog representing the future bounding forward.

Panofsky and Saxl supported this multi-layered solution by drawing on two previously-unrelated traditions. The first of these was the traditional depiction of Prudence as having three heads or faces (Fig 3). The second tradition, which explained the presence of the animal heads, was traced back to a creature which accompanied the Hellenistic Egyptian god Serapis. This creature had the heads of a wolf, lion and dog (Fig 4). At least since the fifth century [10]. this three-headed creature has been regarded as an embodiment of Time, with the voracious wolf representing the past which devours the memory of all things, the vigorous lion representing the present and the dog representing the future bounding forward.

An obvious question that arises about this type of analysis is whether it is reasonable to believe that Titian himself was aware of all these classical and ancient allusions that Panofsky attributes to the work. It does appear, however, that these concepts were quite common in Venetian circles at the time. The image of a three headed Prudence had appeared before in Italy [11], and the image of Serapis’s accomplice as “time monster” had been revived in somewhat altered form in books published in the mid-sixteenth century [12].

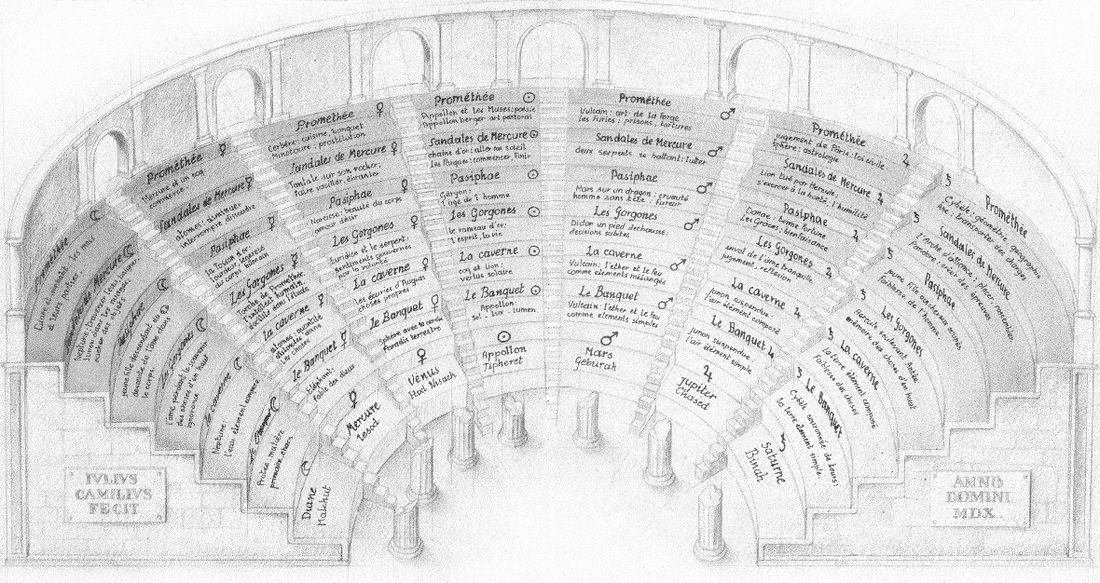

A possibly even more direct link is provided by the extraordinary Venetian character Giulio Camillo [13]. To explain his relevance, however, it is necessary to provide some brief background. Although now largely forgotten, Camillo was apparently one of the most famous men of his times [14]. He claimed to have invented a mysterious Memory Theatre, a “work of wonderful skill” that would enable anyone who was admitted as a spectator to be able to discourse on any subject as fluently as Cicero [15]. The Theatre was based on Camillo’s conviction that all things that the human mind could conceive could be organised in a particular way, reflecting the eternal order of things. Furthermore, they could be expressed by certain “corporeal signs” so that the viewer could immediately perceive “everything that is otherwise hidden in the depths of the human mind”. It was never quite clear whether the Theatre, with its semi-mystical Seven Pillars of Wisdom and drawers or boxes of coded information, was really meant to be a physical structure, or was just meant as be a metaphor [16], and in any event Camillo never actually produced the final product. But the sheer grandeur and audacity of the concept, along its essential vagueness, attracted extravagant public interest, and even financial support from Francis I, the King of France.

Fortunately, Camillo did produce some documentary evidence of his idea, in a book published in Florence and Venice, L’Idea del Theatro dell’eccellen. M Giulio Camillo [17]. This reveals that in one part of the Memory Theatre – the “Cave” grade of the “Saturn” Pillar – there is an entry that is of special interest to us. That entry simply reads “Heads of a wolf, lion and dog: past, present and future”. Given Camillo’s fame, the fact that the book was published in 1550 – just a few years before Titian is believed to have started his Allegory -- and the fact that Camillo and Titian moved in the same Venetian artistic and literary circles [18], it is quite reasonable to believe that Titian would have been well aware of this time-related relationship between the three animal heads.

A possibly even more direct link is provided by the extraordinary Venetian character Giulio Camillo [13]. To explain his relevance, however, it is necessary to provide some brief background. Although now largely forgotten, Camillo was apparently one of the most famous men of his times [14]. He claimed to have invented a mysterious Memory Theatre, a “work of wonderful skill” that would enable anyone who was admitted as a spectator to be able to discourse on any subject as fluently as Cicero [15]. The Theatre was based on Camillo’s conviction that all things that the human mind could conceive could be organised in a particular way, reflecting the eternal order of things. Furthermore, they could be expressed by certain “corporeal signs” so that the viewer could immediately perceive “everything that is otherwise hidden in the depths of the human mind”. It was never quite clear whether the Theatre, with its semi-mystical Seven Pillars of Wisdom and drawers or boxes of coded information, was really meant to be a physical structure, or was just meant as be a metaphor [16], and in any event Camillo never actually produced the final product. But the sheer grandeur and audacity of the concept, along its essential vagueness, attracted extravagant public interest, and even financial support from Francis I, the King of France.

Fortunately, Camillo did produce some documentary evidence of his idea, in a book published in Florence and Venice, L’Idea del Theatro dell’eccellen. M Giulio Camillo [17]. This reveals that in one part of the Memory Theatre – the “Cave” grade of the “Saturn” Pillar – there is an entry that is of special interest to us. That entry simply reads “Heads of a wolf, lion and dog: past, present and future”. Given Camillo’s fame, the fact that the book was published in 1550 – just a few years before Titian is believed to have started his Allegory -- and the fact that Camillo and Titian moved in the same Venetian artistic and literary circles [18], it is quite reasonable to believe that Titian would have been well aware of this time-related relationship between the three animal heads.

is it about financial planning?

Panofsky later elaborated on his analysis by suggesting that there was a fourth level of meaning, one which had particular personal significance to Titian [19]. This interpretation rested on identifying the human faces with real people, and the subject matter with a real-life narrative. On this interpretation, the head on the left is said to represent an aged Titian himself (born about 1488), the central bearded man represents his son Orazio (born 1825), and the youth depicts his young cousin and heir, Marco Vecellio (born 1845) [20]. Panofsky also suggests that the painting is specifically associated with the negotiations associated with the passing on of Titian’s property to the younger generations, in the light of his rapidly advancing death. So, the painting acts as a visual counsel to all parties to act prudently in the administration of their inheritance. Following a suggestion made earlier by von Hadeln, Panofsky further suggests that the painting may even have acted as a cover for the family’s strongbox of valuables.

While this is tidy, it is certainly open to challenge. On the identification issue, Panofsky said that that there is “no doubt” about the Titian figure, and indeed there are certainly similarities with a self-portrait by Titian [Fig 5] and also with the red-capped head of a figure identified as Titian in Veronese’s Marriage at Cana 1563 [21]. However, if the Allegory really depicts Titian, the artist must have had a rather tortured self-image at the time he was painting it – the depiction is extremely unflattering, and the expression is extraordinarily fierce, even furious, far more tortured than the Prado portrait. It comes close to a caricature. Oddly, too, the eyes appear to have darkened, compared with early portraits.

While this is tidy, it is certainly open to challenge. On the identification issue, Panofsky said that that there is “no doubt” about the Titian figure, and indeed there are certainly similarities with a self-portrait by Titian [Fig 5] and also with the red-capped head of a figure identified as Titian in Veronese’s Marriage at Cana 1563 [21]. However, if the Allegory really depicts Titian, the artist must have had a rather tortured self-image at the time he was painting it – the depiction is extremely unflattering, and the expression is extraordinarily fierce, even furious, far more tortured than the Prado portrait. It comes close to a caricature. Oddly, too, the eyes appear to have darkened, compared with early portraits.

The other depictions too are questionable. Panofsky says that Orazio’s identification is “unmistakeably” the same as the image of Orazio in the Mater Misercorcordia at Palazzo Pitti Florence. This is perhaps an exaggeration, as the portraits are no more than broadly consistent. Furthermore, the identification of the youthful Marco Vecellio is little more than an unverified speculation. National Gallery curator Nicholas Penny has pointed out that the head of the youth is in fact very similar to other poorly-executed figures added by Titian’s assistants in his Portrait of the Vendramin Family (1550-60), which may suggest that the youth’s head is generic and not intended to be a real person [22].

Panofsky’s suggestion that the painting has this personal level of meaning is also weakened in a more general way. It is generally now acknowledged that the work is not entirely by Titian’s hand alone [23]. Indeed, Penny inclines to the view that only the central head can be confidently attributed to him, with the other heads, the inscription and the animals all being done later by assistants [24]. Yet if Titian meant the painting to be an admonition to the others to act in a unified and prudent manner, it seems strange that he would allow this to be presented in such an uneven way, both in terms of style and quality.

Of course, this is not to say that Panofsky’s “personal narrative” level of interpretation is not correct, but merely to say that it requires further confirmation before it can move from the merely plausible to the probable. It also needs to be pointed out that the fact that one of the faces may be based on a real person does not mean that the others must also be based on real persons. It may simply be that the faces are just typical of people at different stages of life, and that the artist used himself as a model for one them.

Panofsky’s suggestion that the painting has this personal level of meaning is also weakened in a more general way. It is generally now acknowledged that the work is not entirely by Titian’s hand alone [23]. Indeed, Penny inclines to the view that only the central head can be confidently attributed to him, with the other heads, the inscription and the animals all being done later by assistants [24]. Yet if Titian meant the painting to be an admonition to the others to act in a unified and prudent manner, it seems strange that he would allow this to be presented in such an uneven way, both in terms of style and quality.

Of course, this is not to say that Panofsky’s “personal narrative” level of interpretation is not correct, but merely to say that it requires further confirmation before it can move from the merely plausible to the probable. It also needs to be pointed out that the fact that one of the faces may be based on a real person does not mean that the others must also be based on real persons. It may simply be that the faces are just typical of people at different stages of life, and that the artist used himself as a model for one them.

Is it about sin and penitence?

Although we know the painting under the title of Allegory of Prudence, this is a comparatively recent name, stemming more from its interpretation than any identification by Titian. Simona Cohen has actually argued that the allegory is really more about Christian conceptions of sin, and its relationship to the stages of human existence and to the dimensions of time. In particular, it presents a personal statement by Titian, a message of self-accusation and remorse, as he (supposedly) confronts issues of sin and penitence in his old age [25].

On this drama-charged interpretation, the central human face represents the sixteenth-century Venetian ideal of manhood (virilità), and the youth, with his fair golden locks and lavish clothes, conforms to literary personifications of voluptuousness (luxuria). The tortured old man, the real subject, is indeed Titian.

Cohen also suggests that the beasts are not directly related to time, but instead conform with traditional concepts of moral transgression – luxuria (represented by a dog or leopard), superbia (pride, represented by a lion) and avarita (greed, represented by a wolf). These concepts, she argues, can be indirectly linked to the three ages of man – the sensuality of youth, the pride of middle age and the greed of old age.

This interpretation certainly would explain the negative self-image of Titian in the painting, as the artist can be interpreted as admitting that his failure to act prudently in his “voluptuous” youth or his “prideful” maturity has condemned him to lead a tortured and regretful old age. Cohen claims that Titian was moved to do this by major religious stirrings and his anxieties of impending death, although she agrees that there is no written documentation regarding Titian’s convictions or personal interests in reformatory movements.

However, it is initially difficult to see how this interpretation relates to the inscription that “from the past /the present acts prudently/lest it spoil future action”. The positioning of the inscription seems to proceed on the basis that the past is represented by the old man and the future by the young man. Yet Cohen’s interpretation appears to be based on the youth and the middle-aged man both being in the past, as Titian – in the present –views it in his old age.

Probably, however, too much can be made of this objection. Whether one represents the present, the past or the future depends entirely on one’s point of view. So, for example, assuming Titian is the old man, he represents the present to himself, but to the others (and possibly himself) he also represents the past, in the sense that he comes from an earlier time. He also represents the future, in the sense that he is the future of what they could turn out to be. The youth represents the present to himself, but to the others he also represents the past, in the sense that they were once like him, and also the future, in the sense that he will probably outlive them.

On this drama-charged interpretation, the central human face represents the sixteenth-century Venetian ideal of manhood (virilità), and the youth, with his fair golden locks and lavish clothes, conforms to literary personifications of voluptuousness (luxuria). The tortured old man, the real subject, is indeed Titian.

Cohen also suggests that the beasts are not directly related to time, but instead conform with traditional concepts of moral transgression – luxuria (represented by a dog or leopard), superbia (pride, represented by a lion) and avarita (greed, represented by a wolf). These concepts, she argues, can be indirectly linked to the three ages of man – the sensuality of youth, the pride of middle age and the greed of old age.

This interpretation certainly would explain the negative self-image of Titian in the painting, as the artist can be interpreted as admitting that his failure to act prudently in his “voluptuous” youth or his “prideful” maturity has condemned him to lead a tortured and regretful old age. Cohen claims that Titian was moved to do this by major religious stirrings and his anxieties of impending death, although she agrees that there is no written documentation regarding Titian’s convictions or personal interests in reformatory movements.

However, it is initially difficult to see how this interpretation relates to the inscription that “from the past /the present acts prudently/lest it spoil future action”. The positioning of the inscription seems to proceed on the basis that the past is represented by the old man and the future by the young man. Yet Cohen’s interpretation appears to be based on the youth and the middle-aged man both being in the past, as Titian – in the present –views it in his old age.

Probably, however, too much can be made of this objection. Whether one represents the present, the past or the future depends entirely on one’s point of view. So, for example, assuming Titian is the old man, he represents the present to himself, but to the others (and possibly himself) he also represents the past, in the sense that he comes from an earlier time. He also represents the future, in the sense that he is the future of what they could turn out to be. The youth represents the present to himself, but to the others he also represents the past, in the sense that they were once like him, and also the future, in the sense that he will probably outlive them.

or is it about the practice of art?

More recently, a quite different interpretation of the painting has been reached by Erin Campbell [26]. While accepting Panofsky’s identification of the human heads, she argues that the theme of prudence in the painting is not related to issues of financial stability (as Panofsky suggests) or of repentance for sin (as Cohen suggests). Rather, prudence is closely associated with the crucial role of elderly artists. This, she says, is why the aged characteristics of Titian have been so exaggerated in the painting, by being made darker, more spare and less distinct than the brightness of the forward looking youth on the right [27].

On this view, the painting is thus intended as a counter to the views of contemporaries, such as Vasari, that old age was the enemy of artistic achievement, On the contrary, argues Campbell, the painting is meant to suggest that the prudence that comes with experience and old age is an essential aspect of artistic discrimination and judgment. On a more general level, the painting’s depiction of Titian with his assistants Orazio and Marco is also intended as a defence of the prudence of the continuity of the Venetian workshop tradition against Vasari’s enshrinement of individual genius. And, on yet another level, the bold variations in brushwork used to eloquently identify each face are meant to serve as a defence of the Venetian embrace of the “colorito” style (based on brushwork) over the “disegno” style (based on draughtsmanship) that was popular in Florence and championed by Vasari..

However, there are some difficulties with this approach. If the painting is meant to depict the virtues of old age for artists, why does Titian looks so angry and decidedly un-serene about it? And if the painting is meant as Titian’s ringing public defence of Venetian studio practices, why did it not see the light of day for decades after his death?

On this view, the painting is thus intended as a counter to the views of contemporaries, such as Vasari, that old age was the enemy of artistic achievement, On the contrary, argues Campbell, the painting is meant to suggest that the prudence that comes with experience and old age is an essential aspect of artistic discrimination and judgment. On a more general level, the painting’s depiction of Titian with his assistants Orazio and Marco is also intended as a defence of the prudence of the continuity of the Venetian workshop tradition against Vasari’s enshrinement of individual genius. And, on yet another level, the bold variations in brushwork used to eloquently identify each face are meant to serve as a defence of the Venetian embrace of the “colorito” style (based on brushwork) over the “disegno” style (based on draughtsmanship) that was popular in Florence and championed by Vasari..

However, there are some difficulties with this approach. If the painting is meant to depict the virtues of old age for artists, why does Titian looks so angry and decidedly un-serene about it? And if the painting is meant as Titian’s ringing public defence of Venetian studio practices, why did it not see the light of day for decades after his death?

Conclusion

The Allegory is a perfect example of how a number of respected experts can come to quite different, but credible, interpretations of an artwork. As these interpretations cannot all be entirely correct, it may be seen as posing a problem – which do you believe? Perhaps, however, this is not really a problem. “Certainty” is not necessarily a realistic goal in this type of enquiry. Where experts’ interpretations differ (or even if they don’t), the viewer must ultimately come to their own conclusions, tentative as they may be, based on their own critical judgment, degree of knowledge and preferences. For example, you might consider that, on balance, Panofsky’s basic analysis of prudence and time feels convincing, though doubts remain about his identification of the human figures and their personal significance to Titian. And you might believe that Campbell’s analysis, with its stress on old age and artistry, provides an intriguingly different type of elaboration which is impressive in its erudition, but leaves open some practical questions. You might appreciate Cohen’s boldly-original interpretation, involving penitence and sin, but have the reservation that we may not know enough about Titian’s inner life to justify conclusions about his intimate feelings. And you might reluctantly conclude that the political interpretation put forward by Remy, while understandable in its contemporary context, has obvious factual problems. Or, then again… you might not [28].

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Titian, Prudence and the three-headed beast", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Titian, Prudence and the three-headed beast", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

End notes

[1] Real name Tiziano Vecellio (ca 1488-1576).

[2] Sheila Hale, Titian: His Life, Harper Press, London, 2012 at 730.

[3] Nicholas Penny, The National Gallery Catalogue of Sixteenth-Century Italian Paintings, London, 2008, vol 2 p 236 at 242.

[4] An allegory is a work that can be understood on two or more levels. The primary level is what it actually depicts and the secondary level is its deeper or more abstract meaning.

[5] Penny, op cit at 242.

[6] Hale, op cit at 730.

[7] It is possible that the inscription was not particularly visible in its uncleaned state: Penny, op cit at 238.

[8] Baron von Hadeln Detley, “Some Little-known Works by Titian”, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, May XLV, 1924 at 178.

[9] Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, 'A Late -Antique Religious Symbol in Works by Holbein and Titian', The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, XLIX (1926), 177. See also Penny, op cit, and Kristen Lippincott and ors, “The Depiction of Time” in The Story of Time, Merrell Holberton, in association with National Maritime Museum, London, 1999.

[10] The Roman philosopher Macrobius described it in this way in his Saturnalia.

[11] Though this image lacked the element of time.

[12] For example, in Pierio Valeriano’s Hierglyphica (1556), based on Macrobius’ description.

[13] Full name Giulio Camillo Delmoninio.

[14] Frances A Yates, The Art of Memory, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1974 edn at 129.

[15] Yates, op cit at 130-131.

[16] The concept has eerie parallels with Alan Turing’s 1936 “Universal Machine”, which embodied many of the basic ideas of the modern digital computer: see generally George Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral: The Origins of the Digital Universe, Allen Lane, London, 2012.

[17] Yates, op cit at 136.

[18] Yates, op cit at 162.

[19] Erwin Panovsky, “Titian’s Allegory of Prudence: A Postscript” in Meaning in the Visual Arts, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1982 edn.

[20] Both Orazio and Marco worked as assistants in Titian’s studio.

[21] Simona Cohen, “Titian's London Allegory and the three beasts of his selva oscura”, Renaissance Studies, 2000 (Vol 14, No 1) p 46. Cohen describes the work as the “so-called” Allegory of Prudence.

[22] Penny, op cit at 214.

[23] Bernard Berenson was the first to suggest this: Penny, op cit at 238.

[24] In her recent biography, Shelia Hale describes the painting as a “not entirely successful pastiche”: op cit at 730.

[25] Cohen, op cit.

[26] Erin J Campbell, “Old Age and the politics of Judgment in Titian’s allegory of prudence”, Word and Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Poetry, Vol 19 iss 4 2003, p 261.

[27] This would explain why the light needs to come in from the right, even though the right-handed Titian would normally portray light as coming from the left.

[28] And for a complete contrast, you may be interested in a view that the painting is not by Titian at all, but dates from the seventeenth century and is by the Venetian artist Palma il Giovane (1544-1628), depicting himself (centre) and his two artistic idols Palma il Vecchio (right) and Titian (left), with each painted in their own distinctive styles: Svend Erik Hendriksen http://www.artlyst.com/articles/is-titians-allegory-of-prudence-a-misattribution, 21 August 2011.

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

Mode of citation: McCouat, P, "Titian, Prudence and the three-headed beast", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home

[2] Sheila Hale, Titian: His Life, Harper Press, London, 2012 at 730.

[3] Nicholas Penny, The National Gallery Catalogue of Sixteenth-Century Italian Paintings, London, 2008, vol 2 p 236 at 242.

[4] An allegory is a work that can be understood on two or more levels. The primary level is what it actually depicts and the secondary level is its deeper or more abstract meaning.

[5] Penny, op cit at 242.

[6] Hale, op cit at 730.

[7] It is possible that the inscription was not particularly visible in its uncleaned state: Penny, op cit at 238.

[8] Baron von Hadeln Detley, “Some Little-known Works by Titian”, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, May XLV, 1924 at 178.

[9] Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, 'A Late -Antique Religious Symbol in Works by Holbein and Titian', The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, XLIX (1926), 177. See also Penny, op cit, and Kristen Lippincott and ors, “The Depiction of Time” in The Story of Time, Merrell Holberton, in association with National Maritime Museum, London, 1999.

[10] The Roman philosopher Macrobius described it in this way in his Saturnalia.

[11] Though this image lacked the element of time.

[12] For example, in Pierio Valeriano’s Hierglyphica (1556), based on Macrobius’ description.

[13] Full name Giulio Camillo Delmoninio.

[14] Frances A Yates, The Art of Memory, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1974 edn at 129.

[15] Yates, op cit at 130-131.

[16] The concept has eerie parallels with Alan Turing’s 1936 “Universal Machine”, which embodied many of the basic ideas of the modern digital computer: see generally George Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral: The Origins of the Digital Universe, Allen Lane, London, 2012.

[17] Yates, op cit at 136.

[18] Yates, op cit at 162.

[19] Erwin Panovsky, “Titian’s Allegory of Prudence: A Postscript” in Meaning in the Visual Arts, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1982 edn.

[20] Both Orazio and Marco worked as assistants in Titian’s studio.

[21] Simona Cohen, “Titian's London Allegory and the three beasts of his selva oscura”, Renaissance Studies, 2000 (Vol 14, No 1) p 46. Cohen describes the work as the “so-called” Allegory of Prudence.

[22] Penny, op cit at 214.

[23] Bernard Berenson was the first to suggest this: Penny, op cit at 238.

[24] In her recent biography, Shelia Hale describes the painting as a “not entirely successful pastiche”: op cit at 730.

[25] Cohen, op cit.

[26] Erin J Campbell, “Old Age and the politics of Judgment in Titian’s allegory of prudence”, Word and Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Poetry, Vol 19 iss 4 2003, p 261.

[27] This would explain why the light needs to come in from the right, even though the right-handed Titian would normally portray light as coming from the left.

[28] And for a complete contrast, you may be interested in a view that the painting is not by Titian at all, but dates from the seventeenth century and is by the Venetian artist Palma il Giovane (1544-1628), depicting himself (centre) and his two artistic idols Palma il Vecchio (right) and Titian (left), with each painted in their own distinctive styles: Svend Erik Hendriksen http://www.artlyst.com/articles/is-titians-allegory-of-prudence-a-misattribution, 21 August 2011.

© Philip McCouat 2013, 2014

Mode of citation: McCouat, P, "Titian, Prudence and the three-headed beast", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home