Julie Manet, Renoir and the Dreyfus Affair

|

By Philip McCouat

In 1893, a young French girl started a diary which she would maintain for the rest of her teenage years. “I have always wanted to keep a diary,” she noted determinedly, “so I think I’ll start one now” [1]. |

------------------------------

For more on the Impressionists, see Floating pleasure worlds of Paris and Edo ------------------------------- |

The girl’s name was Julie Manet (Fig 1), and she came from a truly remarkably artistic family. Her father, Eugène, was Ėdouard Manet’s younger brother, and her mother was the prominent Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot (Fig 2), who claimed family links going back to Fragonard. The family counted Renoir, Degas and the poet Mallarmé among their close family friends.

Julie’s diary was no “neat ladylike leather bound volume, but untidy notes scribbled down in old exercise books, often in pencil, the presentation as spontaneous as the contents”[2]. Fortunately for us, however, the diary has survived and has been published, in edited form [3], illustrated with photographs and paintings of the personalities and incidents involved. It provides a quite fascinating first-hand insight into the world of the Impressionists, and of France itself at the turn of the century. What gives the diary its special piquancy, however, is that it coincided precisely with the Dreyfus Affair, one of the most famous controversies in recent French history. This Affair highlighted deep and sometimes violent schisms in French society over attitudes to nationalism, tradition, loyalty, justice, individual rights, religion and anti-Semitism [4].

What Julie recorded about the Affair is the main focus of this article. However, before turning to that, it is worthwhile to give some background about Julie herself.

What Julie recorded about the Affair is the main focus of this article. However, before turning to that, it is worthwhile to give some background about Julie herself.

A privileged life

Julie was born in 1878. Her parents were the artists Berthe Morisot and Eugène

Manet, and the family was highly cultured and wealthy. She had tutors rather than attend school, and was exposed very early to music and art, which she loved, and at which she became quite proficient. From quite a young age, she moved easily in artistic and literary circles, and became familiar with many of the famous artists of the time, such as Monet, Renoir and Degas. Even as a child, she was taken on trips abroad, where she enjoyed visiting galleries and museums, developing a discerning appreciation.

Manet, and the family was highly cultured and wealthy. She had tutors rather than attend school, and was exposed very early to music and art, which she loved, and at which she became quite proficient. From quite a young age, she moved easily in artistic and literary circles, and became familiar with many of the famous artists of the time, such as Monet, Renoir and Degas. Even as a child, she was taken on trips abroad, where she enjoyed visiting galleries and museums, developing a discerning appreciation.

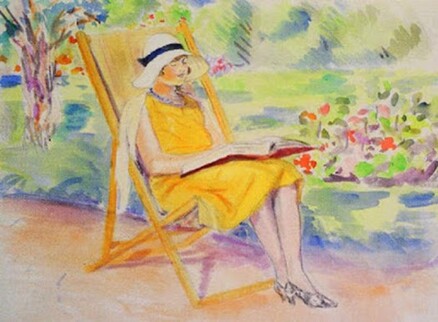

She was an only child, exceptionally attractive, and frequently sat as a model for her mother (Fig 3) and other artists, including Manet and Renoir (Fig 4).

Julie herself also had artistic talent, but little remains of her work. Some sketches and watercolours have survived (Fig 5), and a portrait of a friend unexpectedly surfaced from a private collection in 2021 (published for the first time in Fig 6).

Julie’s seemingly-idyllic life was shattered by the death of both her beloved parents within a three year period, leaving her orphaned at the age of 16. Under the warm guardianship of Stéphane Mallarmé, she went to live with her cousins, with whom she was very close. She also received support from the family’s artist friends. Renoir, in particular, took in Julie for the whole summer following Berthe’s death, showing her great kindness and taking a continuing interest in her welfare.

Julie’s record of her life in the diary ranges from the trivial incidents of life through to moments of great tragedy. Her memories of her father, and of the unexpected death of her mother, are recorded with great poignancy. The overwhelming impression one takes away is of an exceptionally bright, engaging and culturally aware young woman. So, for example, while Julie is obviously very fond and admiring of Renoir, she does not appear to let this colour her remarkably candid first-hand observations of his conversations and behaviour. This particularly comes to the fore in Julie’s references to the Dreyfus Affair.

Julie’s record of her life in the diary ranges from the trivial incidents of life through to moments of great tragedy. Her memories of her father, and of the unexpected death of her mother, are recorded with great poignancy. The overwhelming impression one takes away is of an exceptionally bright, engaging and culturally aware young woman. So, for example, while Julie is obviously very fond and admiring of Renoir, she does not appear to let this colour her remarkably candid first-hand observations of his conversations and behaviour. This particularly comes to the fore in Julie’s references to the Dreyfus Affair.

The Dreyfus Affair

In the 1890s, many people in France were feeling defensive, insecure, xenophobic and nationalistic. After its ignominious defeat in the Franco-Prussian war (1870-71), and the consequent loss of Alsace and Lorraine, France had been severely shaken by the violence associated with the Paris Commune. There were also continuing fears of further wars with its neighbours, Germany and England. In these circumstances, some French people were more than ready to find someone to blame for their misfortunes. Jews formed a highly visible target, with their prominence in French public, financial and intellectual life. There was a considerable rise in the publication of anti-Semitic views, often vitriolically and openly expressed, accusing Jews of working against France’s interests and even plotting its destruction [5].

Against this volatile background, evidence came to light that indicated that someone in the French army was giving secret information to the Germans. Suspicion fell on Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a talented, prosperous but not very popular career officer (Fig 6). Dreyfus was also Jewish. In late 1894, after a hasty investigation, he was convicted of high treason and publicly degraded before a jeering crowd crying crude anti-Jewish insults [6]. He was sentenced to life imprisonment on the notorious Devil’s Island, a remote penal colony off the coast of French Guiana in South America.

Against this volatile background, evidence came to light that indicated that someone in the French army was giving secret information to the Germans. Suspicion fell on Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a talented, prosperous but not very popular career officer (Fig 6). Dreyfus was also Jewish. In late 1894, after a hasty investigation, he was convicted of high treason and publicly degraded before a jeering crowd crying crude anti-Jewish insults [6]. He was sentenced to life imprisonment on the notorious Devil’s Island, a remote penal colony off the coast of French Guiana in South America.

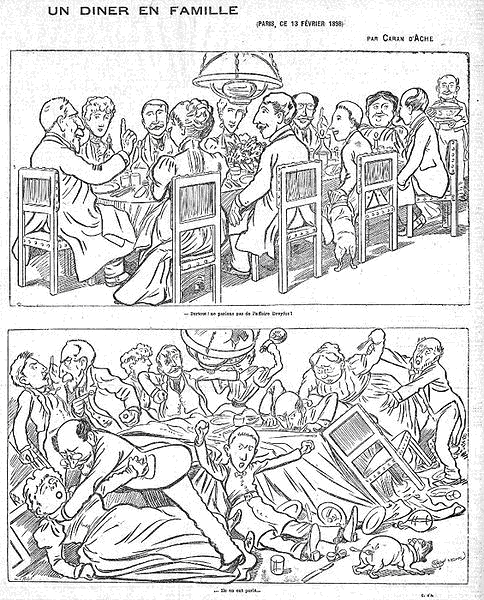

As time went on, however, grave doubts about Dreyfus’ guilt began to gain more currency. Evidence emerged suggesting that another officer, Major Esterhazy, was the real culprit and there had been fabrication of evidence at a high level. People in France became increasingly – and often violently – split in their views, with friend arguing against friend, neighbour against neighbour and family against family (Fig 7). Loyalties were severely tested. At one extreme, people who were right-wing, ultra-nationalist, Catholic and anti-Jewish tended to be against Dreyfus. At the other extreme, those who were left-wing, intellectual, secular or Jewish tended to be Dreyfus supporters. However, as so many factors were involved, many people fell somewhere in between, and in any event there were many exceptions on either side [7].

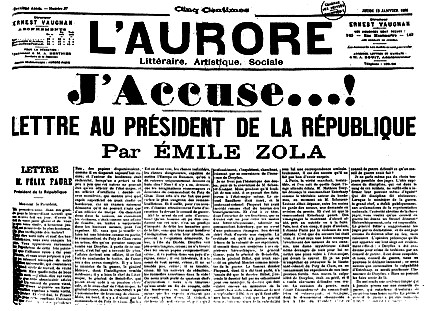

In 1898, the affair took a major turn, when Esterhazy was cleared by a closed military court, prompting Ėmile Zola to publish his famous open letter J’ Accuse…! on the front page of L’Aurore, Georges Clemenceau's pro-Dreyfus newspaper (Fig 7). Zola vehemently claimed that the army had engaged in a massive cover-up, and called on the government to re-open the entire case. He was promptly convicted of criminal libel and, to avoid imprisonment, fled to England [8]. But the pressure forced the new government to order a new trial for Dreyfus. Yet again, Dreyfus was found guilty, but as a political compromise, was pardoned and set free.

Renoir's views on the Affair

Reflecting the wide divergence of views on Dreyfus in the community as a whole, French artists and writers were also split. So, for example, Monet, Pissarro, Proust and Zola were strongly pro-Dreyfus, while Degas, Céezanne, the poet Paul Valéry and Henri Rouart were strongly against [9].

Degas’ views about Dreyfus were conditioned largely by his notorious anti-Semitism, which became progressively more strident and personal as time went by. In combination with his generally argumentative nature, it would eventually result in his losing practically all of his friends, most notably the Halévy family with whom he had been very close [10].

Less well-known, however, are the views of Julie’s beloved Renoir. In Jean Renoir’s sympathetic reminiscences in Renoir, My Father [11], written many years after the event, he presents Renoir as trying hard to steer a middle course in the Affair. Thus, Renoir is quoted as saying, “People are either pro- or anti-Dreyfus. I would try to be simply to be a Frenchman”[12]. According to Jean, Renoir’s advice was to “stay quiet and wait for the ferment to pass”, and he tried to avoid embroiling himself with the extreme views of either Pissarro (himself Jewish and pro-Dreyfusard) or Degas (anti-Dreyfusard). Jean also reports Renoir as fearing that the result of the Affair “might take the form of anti-Semitism among the lower middle class. He could envisage armies of grocers and similar tradesmen, wearing hoods and treating the Jews the way the KKK treated the Negroes”.

According to Jean’s account, Renoir’s decision on one occasion not to join an exhibition with Pissarro and Gauguin was not due to any personal antagonism to Pissarro’s pro-Dreyfus position. Renoir had been approached prior to the exhibition, with Degas anxiously asking him, “Surely you’re not going to do a thing like that, are you?” Renoir responded, “Who? Me? Me exhibit with a gang of Jews and Socialists? You must be mad!”. His son interprets that as a waggish though misguided attempt to lead Degas on [13]. Renoir’s real decision not to exhibit, says Jean, was simply because Renoir could not bear Gauguin’s paintings (“his Breton women look too anaemic”).

However, a rather different impression seems to emerge from Julie’s account. As the editors of the diary point out [14], she regularly records Renoir as expressing a variety of anti-Jewish views. So, for example, in January 1898, during a discussion of the Affair, Julie quotes Renoir as saying, “[The Jews] come to France to earn money, but if there is any fighting to be done they hide behind a tree… There are a lot of them in the army, because the Jew likes to walk about wearing a uniform”. During the same discussion, Julie notes that Renoir also “let fly on the subject of Pissarro, ‘a Jew’, whose sons are natives of no country and who do their military service nowhere”. Renoir goes on, “It’s tenacious the Jewish race. Pissarro’s wife isn’t one, yet all the children are, even more so than their father.”[15]

On another occasion, Julie quotes Renoir talking about how he “naturally” refused to sign a petition which the Jews and anarchists were signing for a reconsideration of the Dreyfus trial. During another interminable discussion, a “very worked up” Renoir observes that “the peculiarity of the Jews is to cause disintegration”. On a later occasion he derides Gustave Moreau’s painting as “art for Jews”[16].

Reading these unguarded comments, it seems that Renoir’s true feelings went beyond mere political conservatism, and were less neutral than his son’s book would suggest.

Degas’ views about Dreyfus were conditioned largely by his notorious anti-Semitism, which became progressively more strident and personal as time went by. In combination with his generally argumentative nature, it would eventually result in his losing practically all of his friends, most notably the Halévy family with whom he had been very close [10].

Less well-known, however, are the views of Julie’s beloved Renoir. In Jean Renoir’s sympathetic reminiscences in Renoir, My Father [11], written many years after the event, he presents Renoir as trying hard to steer a middle course in the Affair. Thus, Renoir is quoted as saying, “People are either pro- or anti-Dreyfus. I would try to be simply to be a Frenchman”[12]. According to Jean, Renoir’s advice was to “stay quiet and wait for the ferment to pass”, and he tried to avoid embroiling himself with the extreme views of either Pissarro (himself Jewish and pro-Dreyfusard) or Degas (anti-Dreyfusard). Jean also reports Renoir as fearing that the result of the Affair “might take the form of anti-Semitism among the lower middle class. He could envisage armies of grocers and similar tradesmen, wearing hoods and treating the Jews the way the KKK treated the Negroes”.

According to Jean’s account, Renoir’s decision on one occasion not to join an exhibition with Pissarro and Gauguin was not due to any personal antagonism to Pissarro’s pro-Dreyfus position. Renoir had been approached prior to the exhibition, with Degas anxiously asking him, “Surely you’re not going to do a thing like that, are you?” Renoir responded, “Who? Me? Me exhibit with a gang of Jews and Socialists? You must be mad!”. His son interprets that as a waggish though misguided attempt to lead Degas on [13]. Renoir’s real decision not to exhibit, says Jean, was simply because Renoir could not bear Gauguin’s paintings (“his Breton women look too anaemic”).

However, a rather different impression seems to emerge from Julie’s account. As the editors of the diary point out [14], she regularly records Renoir as expressing a variety of anti-Jewish views. So, for example, in January 1898, during a discussion of the Affair, Julie quotes Renoir as saying, “[The Jews] come to France to earn money, but if there is any fighting to be done they hide behind a tree… There are a lot of them in the army, because the Jew likes to walk about wearing a uniform”. During the same discussion, Julie notes that Renoir also “let fly on the subject of Pissarro, ‘a Jew’, whose sons are natives of no country and who do their military service nowhere”. Renoir goes on, “It’s tenacious the Jewish race. Pissarro’s wife isn’t one, yet all the children are, even more so than their father.”[15]

On another occasion, Julie quotes Renoir talking about how he “naturally” refused to sign a petition which the Jews and anarchists were signing for a reconsideration of the Dreyfus trial. During another interminable discussion, a “very worked up” Renoir observes that “the peculiarity of the Jews is to cause disintegration”. On a later occasion he derides Gustave Moreau’s painting as “art for Jews”[16].

Reading these unguarded comments, it seems that Renoir’s true feelings went beyond mere political conservatism, and were less neutral than his son’s book would suggest.

Julie's views on the Affair

What then was the attitude of Julie herself?

As a young, orphaned girl, Julie could be expected to be strongly influenced by the views of the people whom she admired and loved. As it happened, these were remarkably uniform – as the editors of the diary point out, the family “seems to have been surrounded by anti-Dreyfusards”[17], including both Degas and Renoir. Ernest Rouart, a fellow artist who would become her future husband, also came from a strong anti-Dreyfus family and, according to Degas, was even involved in hitting a Dreyfusard at a political meeting [18].

In the diary, Julie does not actually mention the Affair until 1897, when she was 18. She describes it as “quite extraordinary” and adds, “How horrible it would be to have condemned this man if he isn’t guilty – but it couldn’t possibly be so” [19]. This final aside is a revealing comment, and is typical of how many French people felt at the time. For them, the role of the army was so elevated, and so inextricably entwined with France’s honour, that it was inconceivable that it could be involved in such chicanery. It followed that a contest between the reputation of the army and the reputation of Dreyfus could have only one result – Dreyfus must be guilty.

Along the same lines, on the occasion of the nomination of Loubet as the new President of the Republic, Julie observes, “It’s horrible to… think that the army is obliged to serve and defend a man who is on the side of its enemies. He can’t be French if he’s a Dreyfusard. I am enraged and heartbroken for our poor country over this latest event. I wish I were a man and could demonstrate and shout slogans. It must be thrilling to engage in politics, but a the same time quite awful.” And again, when she reads the Dreyfusard paper L’Aurore, she recoils: “It’s a disgraceful paper. Such horrors about the army should not be allowed to be written”[20].

However, as the Affair drags on, Julie’s nationalistic views also begin to take on elements of resentment of what she sees as an association between the pro-Drefusards and growing Jewish political influence. In mid-1899, she remarks, “The Dreyfusards…and Jews etc are going to be able to govern at their leisure. Poor France!”. Similarly, she comments, “Loubet is just like his friends the Jews. He puts up with insults and will never resign. And at the time when Dreyfus’s retrial was announced, she exclaims, “How powerful these Jews are!”[21]

Having said that, however, it is clear that Julie did not share the almost obsessional concerns of her mentors. Over dinner one evening she records how “the interminable discussion on the Dreyfus Affair started yet again, with the same things being said once more”. After Renoir makes one of his comments about the Jews, she has clearly had enough. “They may well be interesting but really one has had quite enough of the whole affair by now”, she says, “We… couldn’t think of a thing to say”[22].

As a young, orphaned girl, Julie could be expected to be strongly influenced by the views of the people whom she admired and loved. As it happened, these were remarkably uniform – as the editors of the diary point out, the family “seems to have been surrounded by anti-Dreyfusards”[17], including both Degas and Renoir. Ernest Rouart, a fellow artist who would become her future husband, also came from a strong anti-Dreyfus family and, according to Degas, was even involved in hitting a Dreyfusard at a political meeting [18].

In the diary, Julie does not actually mention the Affair until 1897, when she was 18. She describes it as “quite extraordinary” and adds, “How horrible it would be to have condemned this man if he isn’t guilty – but it couldn’t possibly be so” [19]. This final aside is a revealing comment, and is typical of how many French people felt at the time. For them, the role of the army was so elevated, and so inextricably entwined with France’s honour, that it was inconceivable that it could be involved in such chicanery. It followed that a contest between the reputation of the army and the reputation of Dreyfus could have only one result – Dreyfus must be guilty.

Along the same lines, on the occasion of the nomination of Loubet as the new President of the Republic, Julie observes, “It’s horrible to… think that the army is obliged to serve and defend a man who is on the side of its enemies. He can’t be French if he’s a Dreyfusard. I am enraged and heartbroken for our poor country over this latest event. I wish I were a man and could demonstrate and shout slogans. It must be thrilling to engage in politics, but a the same time quite awful.” And again, when she reads the Dreyfusard paper L’Aurore, she recoils: “It’s a disgraceful paper. Such horrors about the army should not be allowed to be written”[20].

However, as the Affair drags on, Julie’s nationalistic views also begin to take on elements of resentment of what she sees as an association between the pro-Drefusards and growing Jewish political influence. In mid-1899, she remarks, “The Dreyfusards…and Jews etc are going to be able to govern at their leisure. Poor France!”. Similarly, she comments, “Loubet is just like his friends the Jews. He puts up with insults and will never resign. And at the time when Dreyfus’s retrial was announced, she exclaims, “How powerful these Jews are!”[21]

Having said that, however, it is clear that Julie did not share the almost obsessional concerns of her mentors. Over dinner one evening she records how “the interminable discussion on the Dreyfus Affair started yet again, with the same things being said once more”. After Renoir makes one of his comments about the Jews, she has clearly had enough. “They may well be interesting but really one has had quite enough of the whole affair by now”, she says, “We… couldn’t think of a thing to say”[22].

The end of the Affair

Dreyfus was eventually completely exonerated in 1906. He would later rejoin the army and serve in the First World War, being made an Officer of the Legion of Honour and reaching the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He died in 1935, but the schisms revealed by the Affair continue to resound to the present day.

Julie’s diary broke off in 1899, just as she was preparing for her marriage with Ernest Rouart. After their marriage, Julie and Ernest continued their close interest and involvement in art, and helped to organise several major Impressionist exhibitions. They had three sons. Julie outlived Ernest by many years and died in 1966, aged 88.

Renoir continued painting, though becoming increasingly handicapped by arthritis. He died in 1919.

Degas died in 1917, bitterly anti-Semitic to the end.□

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2020, 2021

We welcome your comments on this article.

Julie’s diary broke off in 1899, just as she was preparing for her marriage with Ernest Rouart. After their marriage, Julie and Ernest continued their close interest and involvement in art, and helped to organise several major Impressionist exhibitions. They had three sons. Julie outlived Ernest by many years and died in 1966, aged 88.

Renoir continued painting, though becoming increasingly handicapped by arthritis. He died in 1919.

Degas died in 1917, bitterly anti-Semitic to the end.□

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2020, 2021

We welcome your comments on this article.

Endnotes

[1] Rosalind de Boland Roberts and Jane Roberts, Growing up with the Impressionists: the Diary of Julie Manet, Sotheby’s Publications, London, 1987, at 29.

[2] Roberts, op cit at 9.

[3] Roberts, op cit.

[4] For excellent accounts of the Affair, see Piers Paul Read, The Dreyfus Affair, Bloomsbury, London, 2012; Ruth Harris, The Man on Devil’s Island: Alfred Dreyfus and the Affair that Divided France, Penguin Books. London, 2010. Reference may also be made to Louis Begley, Why the Dreyfus Affair Matters, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2009; and Frederick Brown, For the Soul of France: Culture Wars in the Age of Dreyfus, Alfred A Knopf, New York, 2011. For an historical thriller based on the Affair, see Robert Harris' An Officer and a Spy, Hutchinson, 2013.

[5] See generally Ruth Harris, op cit at 59ff.

[6] Ruth Harris, op cit at 34, 35.

[7] Ruth Harris, op cit, ch 7. Bizarrely, a violent difference of opinion over the Dreyfus Affair also led indirectly to the creation of the Tour de France bicycling race: see Hugh Dauncey and Geoff Hare, The Tour de France, 1903-2003, Routledge, 2013.

[8] Ruth Harris, op cit ch 5.

[9] Toulouse-Lautrec, with a rabidly anti-Dreyfus father, but many Jewish friends, appears to have adopted a studiously neutral position and accepted commissions to illustrate books representing opposing points of view -- Georges Clemenceau's pro-Jewish book Au Pied du Sinaï (1898) and the anti-Semitic Victor Joze's The Tribe of Isidore (1897): see Julia Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec: A Life, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, London, 1994, at 396-9.

[10] Linda Nochlin, The Politics of Vision: Essays on 19th Century Art and Society, Harper and Row, New York, 1989, ch 8; John Richardson, “Degas and the Dancers”, Vanity Fair, October 2002, accessed at http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2002/10/degas200210 (July 2012)

[11] Jean Renoir, Renoir, My Father (transl Randolph and Dorothy Weaver) Collins Fontana Books, London, 1963.

[12] Renoir, op cit at 242.

[13] Renoir, op cit at 243.

[14] Roberts, op cit at 124.

[15] Roberts, op cit at 124.

[16] Roberts, op cit at 127, 129, 182. This comment is directed at Jewish collectors such as Charles Ephrussi, a patron of Renoir himself, who also bought Moreau's works: see also Edmund de Waal, The Hare with Amber Eyes, Windsor Paragon, 2010 ch 9

[17] Roberts, op cit at 24.25.

[18] Roberts, op cit at 152.

[19] Roberts, op cit at 121 (emphasis added).

[20] Roberts, op cit at 162 (emphasis added), 165.

[21] Roberts, op cit at 175, 183.

[22] Roberts, op cit at 129

.

© Copyright Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014,2020, 2021

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Julie Manet, Renoir and the Dreyfus Affair", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to Home

[2] Roberts, op cit at 9.

[3] Roberts, op cit.

[4] For excellent accounts of the Affair, see Piers Paul Read, The Dreyfus Affair, Bloomsbury, London, 2012; Ruth Harris, The Man on Devil’s Island: Alfred Dreyfus and the Affair that Divided France, Penguin Books. London, 2010. Reference may also be made to Louis Begley, Why the Dreyfus Affair Matters, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2009; and Frederick Brown, For the Soul of France: Culture Wars in the Age of Dreyfus, Alfred A Knopf, New York, 2011. For an historical thriller based on the Affair, see Robert Harris' An Officer and a Spy, Hutchinson, 2013.

[5] See generally Ruth Harris, op cit at 59ff.

[6] Ruth Harris, op cit at 34, 35.

[7] Ruth Harris, op cit, ch 7. Bizarrely, a violent difference of opinion over the Dreyfus Affair also led indirectly to the creation of the Tour de France bicycling race: see Hugh Dauncey and Geoff Hare, The Tour de France, 1903-2003, Routledge, 2013.

[8] Ruth Harris, op cit ch 5.

[9] Toulouse-Lautrec, with a rabidly anti-Dreyfus father, but many Jewish friends, appears to have adopted a studiously neutral position and accepted commissions to illustrate books representing opposing points of view -- Georges Clemenceau's pro-Jewish book Au Pied du Sinaï (1898) and the anti-Semitic Victor Joze's The Tribe of Isidore (1897): see Julia Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec: A Life, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, London, 1994, at 396-9.

[10] Linda Nochlin, The Politics of Vision: Essays on 19th Century Art and Society, Harper and Row, New York, 1989, ch 8; John Richardson, “Degas and the Dancers”, Vanity Fair, October 2002, accessed at http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2002/10/degas200210 (July 2012)

[11] Jean Renoir, Renoir, My Father (transl Randolph and Dorothy Weaver) Collins Fontana Books, London, 1963.

[12] Renoir, op cit at 242.

[13] Renoir, op cit at 243.

[14] Roberts, op cit at 124.

[15] Roberts, op cit at 124.

[16] Roberts, op cit at 127, 129, 182. This comment is directed at Jewish collectors such as Charles Ephrussi, a patron of Renoir himself, who also bought Moreau's works: see also Edmund de Waal, The Hare with Amber Eyes, Windsor Paragon, 2010 ch 9

[17] Roberts, op cit at 24.25.

[18] Roberts, op cit at 152.

[19] Roberts, op cit at 121 (emphasis added).

[20] Roberts, op cit at 162 (emphasis added), 165.

[21] Roberts, op cit at 175, 183.

[22] Roberts, op cit at 129

.

© Copyright Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014,2020, 2021

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Julie Manet, Renoir and the Dreyfus Affair", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to Home