Lost in Translation: Bruegel’s Tower of Babel

By Philip McCouat For comments on this article, see here

The Tower that reached to heaven

According to the Old Testament story, God punished humankind in three ways. The first was the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden, following their discovery of Original Sin. Then came the Great Flood, the punishment for humans’ multiplicity of iniquities. And the third was when God, wary of the pride and presumption of the citizens of the thrusting new city of Babylon, “confused the whole world’s speech, and scattered them far away over the wide face of earth” [1].

So, what had the Babylonians done that was so inflammatory? In God’s eyes, they had challenged the order of things by their stated desire to become a “great people”, signified by their construction of a huge tower, “with a top that reaches to heaven” [2]. Humans were not supposed to aspire to such lofty heights, whether physical or metaphorical. God’s chosen punishment for this was to put an end to the common language that had previously united all peoples, and to create a multiplicity of different languages, “so that they will not be able to understand each other”. The resulting confusion meant that “the building of the city came to an end”. According to the Bible, “that is why the city was called Babel” or Babylon [3].

Of all the depictions of this great tower that had so offended God, the most memorable is Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Tower of Babel (1563). It is this painting, and its multiplicity of possible meanings, that we will explore in this article.

So, what had the Babylonians done that was so inflammatory? In God’s eyes, they had challenged the order of things by their stated desire to become a “great people”, signified by their construction of a huge tower, “with a top that reaches to heaven” [2]. Humans were not supposed to aspire to such lofty heights, whether physical or metaphorical. God’s chosen punishment for this was to put an end to the common language that had previously united all peoples, and to create a multiplicity of different languages, “so that they will not be able to understand each other”. The resulting confusion meant that “the building of the city came to an end”. According to the Bible, “that is why the city was called Babel” or Babylon [3].

Of all the depictions of this great tower that had so offended God, the most memorable is Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Tower of Babel (1563). It is this painting, and its multiplicity of possible meanings, that we will explore in this article.

The Tower in history

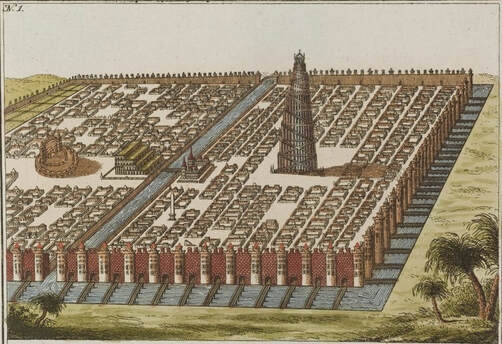

In human history, the building of large tower-temples dates back some 5,000 years. The ancient Sumerians built large, mountain-like temple structures (“ziggurats”) as a method of connecting with their gods [4]. This tradition was later carried on in the cities of Assyria (broadly, present-day Iraq), and the tower at Babylon, the Etemenanki, was reputed to be the highest of them all. Here is how the ancient Greek writer Herodotus described it 458 BC:

“The temple is a square building, two furlongs in each way, with bronze gates, and was still in existence in my time; it has a solid central tower, one furlong square, with a second erected on top of it and then a third, and so on up to eight. All eight towers can be climbed by a spiral way running around the outside, and about half-way up there are seats and a shelter for those who make the ascent to rest on. On the summit of the topmost tower stands a great temple …”[5].

“The temple is a square building, two furlongs in each way, with bronze gates, and was still in existence in my time; it has a solid central tower, one furlong square, with a second erected on top of it and then a third, and so on up to eight. All eight towers can be climbed by a spiral way running around the outside, and about half-way up there are seats and a shelter for those who make the ascent to rest on. On the summit of the topmost tower stands a great temple …”[5].

Within 130 years after this description, however, when Alexander the Great visited Babylon, the Babylon tower was already in ruins [6].

Bruegel’s distinctive version of the Tower

In the Christian account, the Tower at Babylon is not regarded as a temple or monument to God at all, but simply as an example of unacceptable human aspiration. This secularisation of the Tower's meaning may have its origin in the views taken of it by the Jews who had been forced to settle in Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar in 586 BC. They considered the Tower as the ultimate in presumption and blasphemy [7].

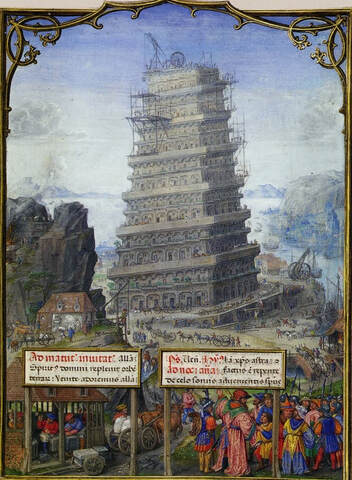

The Tower itself proved to be a popular subject for artists, appearing as a woodcut in German Bibles (Fig 3) or as illuminations in French or Netherlandish texts [8]. But none of these give the impression of colossal size that Bruegel was able to achieve.

The Tower itself proved to be a popular subject for artists, appearing as a woodcut in German Bibles (Fig 3) or as illuminations in French or Netherlandish texts [8]. But none of these give the impression of colossal size that Bruegel was able to achieve.

Bruegel himself depicted the Tower three times, once in an ivory miniature (now lost), and twice in panel paintings, both completed in 1563, including the one we are discussing here, housed at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna [9].

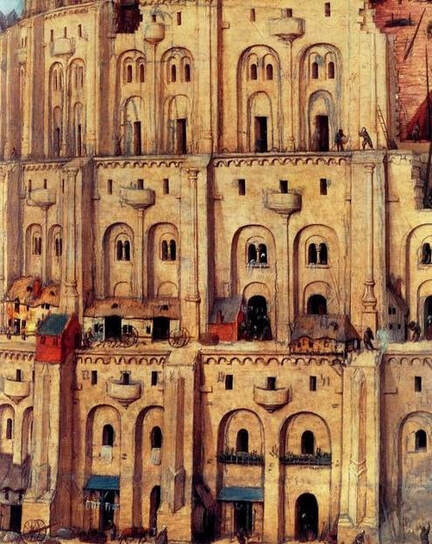

Bruegel’s massive tapering structure (see Fig 1) is made from pale ochre stone, and reaches so high that, shockingly, it actually pierces the clouds in a summery blue sky which is marred only by a looming dark cloud. To appreciate its size, one needs simply to compare it with the four-story fort that adjoins it at the dock (lower right, fig 4) and whose top barely surpasses the base level of the Tower; or with the almost-literally microscopic size of the individual workers.

Bruegel’s massive tapering structure (see Fig 1) is made from pale ochre stone, and reaches so high that, shockingly, it actually pierces the clouds in a summery blue sky which is marred only by a looming dark cloud. To appreciate its size, one needs simply to compare it with the four-story fort that adjoins it at the dock (lower right, fig 4) and whose top barely surpasses the base level of the Tower; or with the almost-literally microscopic size of the individual workers.

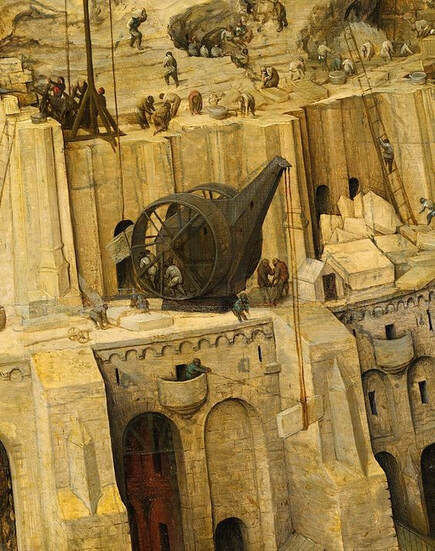

The Tower is encircled by an upward-spiralling ramp, from which multiple arched entrances lead to the dark interior. It teems with workers and construction machinery. Towards the top, the terracotta-coloured inner brick structure is revealed, angling upwards to what seems to be a smaller, more conventional structure at the pinnacle. The building appears to be in a very advanced but uneven state of completion. Indeed, it seems that people are actually living inside, as they would do in modern high-rise apartments, even hanging out their washing, while construction is being carried on all round them.

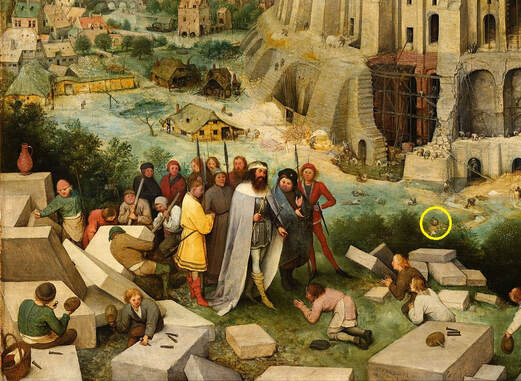

The structure appears to be based on solid rock, and the large, centrally-placed outcrop of rock has remained undressed [10]. It stands close upon the waterfront of a large, busy harbour, where sailing ships and water vessels are moored or ply their trade, chiefly in building materials. Oddly, the entire structure appears to be teetering to the left [11]. In the lower left corner of the painting, among a jumble of stone blocks, workers are paying their respects to a visiting dignitary. And beyond the encircling city, rendered by the artist in extraordinary detail (Fig 5A), there stretches a vast landscape, crossed by rivers, with a low range of hills on the horizon.

A morality tale?

At its simplest level, the painting can be seen a straightforward, dispassionate depiction of the Biblical episode, as the physical setting and reason for God’s punishment of the Babylonians’ pride.

Of course, Biblical stories naturally tend to contain or acquire a moral significance beyond the immediate circumstances in which they are set. So, if the Bible account has God punishing the Tower builders, this would typically be interpreted as a more general warning against over-arching human ambition, and against an approach to life based on material, rather than spiritual, concerns. Bruegel’s longstanding interest in depicting the Tower suggests that it is certainly possible that he shared these concerns, or at least that he appreciated that his audience could be receptive to them.

This interpretation is supported by the likelihood that the size and structure of Bruegel’s Tower was influenced by the structure of the Colosseum in Rome (Fig 6}, with which Bruegel would have been well familiar from his travels in Italy, and from the availability of prints. By Bruegel’s time, the Colosseum, once a shockingly huge symbol of human magnificence in a supposedly-“eternal” city of Rome [12], was in partial ruin. Basing the Tower on it, in the context of a modern 16th century urban setting, was therefore a reminder of the transience of human endeavour, a characteristic that writers at the time frequently associated with ancient ruins in general [13].

Of course, Biblical stories naturally tend to contain or acquire a moral significance beyond the immediate circumstances in which they are set. So, if the Bible account has God punishing the Tower builders, this would typically be interpreted as a more general warning against over-arching human ambition, and against an approach to life based on material, rather than spiritual, concerns. Bruegel’s longstanding interest in depicting the Tower suggests that it is certainly possible that he shared these concerns, or at least that he appreciated that his audience could be receptive to them.

This interpretation is supported by the likelihood that the size and structure of Bruegel’s Tower was influenced by the structure of the Colosseum in Rome (Fig 6}, with which Bruegel would have been well familiar from his travels in Italy, and from the availability of prints. By Bruegel’s time, the Colosseum, once a shockingly huge symbol of human magnificence in a supposedly-“eternal” city of Rome [12], was in partial ruin. Basing the Tower on it, in the context of a modern 16th century urban setting, was therefore a reminder of the transience of human endeavour, a characteristic that writers at the time frequently associated with ancient ruins in general [13].

Further evidence that the Tower was intended as a warning about the sins of human vanity are provided in the previously-mentioned vignette in the lower left of the painting. This shows a luxuriously-dressed, larger-than-life crowned dignitary with his entourage, and is presumably intended to represent King Nimrod, grandson of Noah, who had become a mighty ruler and builder of cities, and who had supposedly commissioned the Tower. The king is visiting on a tour of inspection, and is being greeted by a group of stone-masons. Interestingly, the most prominent mason is not just bending on one knee, the usual gesture of fealty, but is actually on both knees, as if before a representative of God.

Viewers of the painting in 16th century Flanders would presumably interpret this as a totally inappropriate, particularly in the case of someone like King Nimrod, who was described by St Augustine in his City of God as a deceiver and an oppressor, and who, according to one account, had built the tower specifically as revenge for God’s destruction of humanity in the Great Flood

[14]. Bruegel’s disapproval is also perhaps suggested by the tiny detail of a peasant or worker, who has turned away from the scene, and is squatting on the ground, his bare buttocks pointing in the King’s general direction as he defecates [15].

[14]. Bruegel’s disapproval is also perhaps suggested by the tiny detail of a peasant or worker, who has turned away from the scene, and is squatting on the ground, his bare buttocks pointing in the King’s general direction as he defecates [15].

A warning about development….

It has also been suggested that Bruegel was drawing attention to a specific contemporary example of these concerns, by likening the position of Babylon to that of another bustling port city, his home city Antwerp.

Of course, the setting of the Tower in what is obviously an incongruously European setting, rather than a Middle Eastern one, does not in itself signify that Bruegel is using the story to make any more general comment about current affairs; rather, it may simply reflect the current fashion in Protestant countries for depicting Biblical incidents in everyday modern settings [16], and the obvious fact that Bruegel may not have had much idea of how to portray an accurate version of a Middle Eastern city in any event.

Nevertheless, there do appear to be some significant parallels between the two cities. At the time Bruegel was painting, Antwerp, like Babylon. was in the midst of a building boom, with massive influxes of people, threatening to transform what was previously a small port into the “most crowded town in Europe” [17]. The discovery of new sea-routes round the Cape of Good Hope to Asia [18], and across the Atlantic to the recently-discovered Americas [19] had led to a re-orientation of world trade, with Venice and Genoa losing their leading positions as trade shifted to the west of Europe [20]. Cities such as Antwerp were therefore well-placed for transatlantic ship trade, for traffic between north and south, and for imports of spices from the Orient, which had become less accessible since the fall of Constantinople. The combination of its growing population, a building boom and material advancement meant that Antwerp had advanced to become the centre of Western European trade, just as Babylon had been prominent in its own era.

The similarities did not end there. Antwerp’s foreign trade had attracted foreigners to the city, with their foreign languages and customs. The city therefore was faced with potentially the same problem as Babylon ultimately experienced as a result of God’s punishment – a decline in social cohesion due to multiplicity of languages -- which in Babylon’s case ultimately proved to be its downfall. In Antwerp’s case, this risk was even more marked, as the city was also subject to splintering on religious lines.

Of course, the setting of the Tower in what is obviously an incongruously European setting, rather than a Middle Eastern one, does not in itself signify that Bruegel is using the story to make any more general comment about current affairs; rather, it may simply reflect the current fashion in Protestant countries for depicting Biblical incidents in everyday modern settings [16], and the obvious fact that Bruegel may not have had much idea of how to portray an accurate version of a Middle Eastern city in any event.

Nevertheless, there do appear to be some significant parallels between the two cities. At the time Bruegel was painting, Antwerp, like Babylon. was in the midst of a building boom, with massive influxes of people, threatening to transform what was previously a small port into the “most crowded town in Europe” [17]. The discovery of new sea-routes round the Cape of Good Hope to Asia [18], and across the Atlantic to the recently-discovered Americas [19] had led to a re-orientation of world trade, with Venice and Genoa losing their leading positions as trade shifted to the west of Europe [20]. Cities such as Antwerp were therefore well-placed for transatlantic ship trade, for traffic between north and south, and for imports of spices from the Orient, which had become less accessible since the fall of Constantinople. The combination of its growing population, a building boom and material advancement meant that Antwerp had advanced to become the centre of Western European trade, just as Babylon had been prominent in its own era.

The similarities did not end there. Antwerp’s foreign trade had attracted foreigners to the city, with their foreign languages and customs. The city therefore was faced with potentially the same problem as Babylon ultimately experienced as a result of God’s punishment – a decline in social cohesion due to multiplicity of languages -- which in Babylon’s case ultimately proved to be its downfall. In Antwerp’s case, this risk was even more marked, as the city was also subject to splintering on religious lines.

…. or a critique of religious oppression

In a 1568 letter, the Duke of Alba described Antwerp as “a Babylon, a confusion and receptacle of all sects indifferently” [21]. These religious tensions were further exacerbated by the unsympathetic rule of the Catholic Spanish king Phillip II. Indeed, some commentators have argued that the King Nimrod figure in the painting was intended to be seen as code for Phillip, who was forcing the Spanish language upon the unwilling occupants, and attempting to forcibly suppress Protestant or foreign religious beliefs and persecute their followers. This situation was causing considerable alarm in humanist circles, with which Bruegel may have been associated [22]. Some commentators have developed this point further, suggesting that Bruegel is using the Tower story as a means of attacking the Church of Rome itself. On this interpretation, the Colosseum-based Tower is identified with the Church, with both being built upon a rock [23] and both being identified with Rome; the teachings of the Church are seen as confusing the true message of Christ, creating a "babble" of competing creeds; and the Tower’s future crumbling is suggestive of a forecasted waning of the Church's power.

A call for considered action

Of course, just because Bruegel may be likening Antwerp to Babylon does not mean that he believed that Antwerp was likewise headed for destruction, or even that he is necessarily opposed to its development or diversity. But it is arguable that by depicting a prime example of human transience and vanity, and linking it to Antwerp, he is drawing attention to trends that will require attention if Antwerp’s future is to be secured. This could include ensuring that its rapid development and diversification did not lead to Babylonian miscommunication and disunity, while ensuring that the welfare of the whole community was given priority over individuals’ own private gains [24]. And all this needed to be achieved despite the political, linguistic, cultural and religious tensions that we have described.

In this connection, it has been argued that the painting served as an active backdrop for dinner parties hosted by Niclaes Jonghelinck, the prosperous Antwerp banker in whose home the painting was hung. It could thus act to stimulate discussion among engaged citizens of “the dangers of miscommunication, urging those participating in a meal gathering to answer the question of how to maintain prosperity in a community characterized by extraordinary pluralism''. It could present "an open-ended visual argument, which stimulated discussion and self-examination” [25].

In this connection, it has been argued that the painting served as an active backdrop for dinner parties hosted by Niclaes Jonghelinck, the prosperous Antwerp banker in whose home the painting was hung. It could thus act to stimulate discussion among engaged citizens of “the dangers of miscommunication, urging those participating in a meal gathering to answer the question of how to maintain prosperity in a community characterized by extraordinary pluralism''. It could present "an open-ended visual argument, which stimulated discussion and self-examination” [25].

But has the Tower already failed?

This raises another fundamental question. We know that in the Biblical version of the story, the magnificent Tower project ultimately fails. But what stage in the story has Bruegel depicted? And is it even possible that its fate could still be reversed?

It is suggested that Bruegel has shown the Tower at a point before any actual failure takes place. Indeed, the painting provides what has generally been accepted to be an accurate depiction of properly functioning building machinery and methods. Close examination reveals an enormous level of activity being conducted over large parts of the site, including the harbour. All types of trade are represented -- stonemasons, carpenters, plasterers, bricklayers, mortar mixers and tinsmiths – each with their own guild hut. Various pulleys and cranes are being used to transport building materials [26]. The crane on the second level, for example, is shown to be lifting a block of stone, powered by three men in a circular treadmill. Below the ledge, another worker holding a long pole to make sure the stone stays stable [27]. Masons are cutting the stone that has probably been transported to the site by sea. Scaffolding and ladders support workers at high levels. Horses are being used to move heavy loads along the ramps. Bricks are being carried up the Tower [28].

It is suggested that Bruegel has shown the Tower at a point before any actual failure takes place. Indeed, the painting provides what has generally been accepted to be an accurate depiction of properly functioning building machinery and methods. Close examination reveals an enormous level of activity being conducted over large parts of the site, including the harbour. All types of trade are represented -- stonemasons, carpenters, plasterers, bricklayers, mortar mixers and tinsmiths – each with their own guild hut. Various pulleys and cranes are being used to transport building materials [26]. The crane on the second level, for example, is shown to be lifting a block of stone, powered by three men in a circular treadmill. Below the ledge, another worker holding a long pole to make sure the stone stays stable [27]. Masons are cutting the stone that has probably been transported to the site by sea. Scaffolding and ladders support workers at high levels. Horses are being used to move heavy loads along the ramps. Bricks are being carried up the Tower [28].

So, while the Tower is obviously unfinished, there little obvious sign in the painting that the workers have been thrown into confusion, or are failing to cooperate. However, Bruegel has given us some clues that the seeds of possible destruction may already have been built into the structure. For one thing, it has been built unnervingly close to the water. Further, despite some disagreement on the issue [29], the Tower, although built on rock, appears to be clearly tilting to the left, with the result that if it is pushed higher it might eventually topple under its own weight. This is accentuated by the fact that the arches are built at right angles to the sloping ramp. The whole structure therefore seems physically unbalanced and out of kilter, possibly reflecting the lack of balance between the physical and the spiritual in the Babylonians’ approach to life.

In one sense, depicting the Tower before the moment when God has decided its fate, or actually imposed his punishment, can be seen as reflecting a view that a counter-action, or a change in behaviour to correct the errors, still might be possible, difficult though that may be. Some commentators, however, have adopted a rather more critical view of the construction of the Tower, and of whether progress is still being made. So, they suggest that it is not just that the seeds of possible failure have been sown, but that the failure has already, inevitably and irretrievably, begun.

So, for example, these commentators note that the work does not appear to be proceeding in a coordinated way according to some logical plan. Wied says that the picture depicts the moment at which construction has become completely bogged down and is coming to an end; and cites the view directed at the Rotterdam version that at the very top “chaos reigns” [30]. Foote comments that the Tower’s mere appearance suggests that it “will clearly never be finished” [31]. Similarly, the Roberts-Joneses say that the architecture is unrealistic, not functional and absurd, and that the construction techniques being used are incompatible [32].

Are these commentators reading too much into this? We may never know whether Bruegel actually intended that aspects such as these should be taken as signs of failure. For example, the fact that everything appears to be being done at different stages may not be intended as a sign of a failure of coordination, but simply be because Bruegel is aiming to show off as many construction techniques as possible in the one painting. Similarly, although he was well-versed in construction methods, Bruegel may not have intended that a proper appreciation of the painting should require viewers to have an erudite appreciation of the compatibility or otherwise of various architectural styles. The painting is, after all, a sustained feat of imagination on his part.

In one sense, depicting the Tower before the moment when God has decided its fate, or actually imposed his punishment, can be seen as reflecting a view that a counter-action, or a change in behaviour to correct the errors, still might be possible, difficult though that may be. Some commentators, however, have adopted a rather more critical view of the construction of the Tower, and of whether progress is still being made. So, they suggest that it is not just that the seeds of possible failure have been sown, but that the failure has already, inevitably and irretrievably, begun.

So, for example, these commentators note that the work does not appear to be proceeding in a coordinated way according to some logical plan. Wied says that the picture depicts the moment at which construction has become completely bogged down and is coming to an end; and cites the view directed at the Rotterdam version that at the very top “chaos reigns” [30]. Foote comments that the Tower’s mere appearance suggests that it “will clearly never be finished” [31]. Similarly, the Roberts-Joneses say that the architecture is unrealistic, not functional and absurd, and that the construction techniques being used are incompatible [32].

Are these commentators reading too much into this? We may never know whether Bruegel actually intended that aspects such as these should be taken as signs of failure. For example, the fact that everything appears to be being done at different stages may not be intended as a sign of a failure of coordination, but simply be because Bruegel is aiming to show off as many construction techniques as possible in the one painting. Similarly, although he was well-versed in construction methods, Bruegel may not have intended that a proper appreciation of the painting should require viewers to have an erudite appreciation of the compatibility or otherwise of various architectural styles. The painting is, after all, a sustained feat of imagination on his part.

Conclusion

he Biblical story is that the Tower failed because of a lack of communication, caused by the God-inspired outbreak of a multiplicity of languages. In a real sense, therefore, the Tower became lost in translation. When we look at Bruegel’s painting, and attempt to interpret it, we are also engaged in an exercise in translation -- was he simply giving visual expression to the Biblical story? Or was he attempting to make some wider point? Or a combination of both?

We should not be surprised that there is not necessarily agreement about Bruegel’s intentions. It may well be that Bruegel was being deliberately ambiguous, as free expression of controversial political or religious views was not welcomed in his era. Instead of being openly polemic, he has therefore embedded his work with signs, and leaves it up to us, the viewers, to interpret them for ourselves ■

© Philip McCouat 2019, 2021. First published October 2019.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Lost in Translation: Bruegel’s Tower of Babel”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

For other articles on Bruegel in this Journal, see:

Perception and Blindness in the 16th Century: Pieter Bruegel’s ‘The Blind leading the Blind’

The Emergence of the Winter Landscape: Bruegel and his Predecessors

“All Life is Here”: Bruegel’s ‘Way to Calvary’

Bruegel’s ‘Icarus’ and the Perils of Flight

Bruegel's Peasant Wedding Feast: the case of the missing bridegroom and other mysteries

Bruegel's White Christmas: The Census at Bethlehem

Return to HOME

We should not be surprised that there is not necessarily agreement about Bruegel’s intentions. It may well be that Bruegel was being deliberately ambiguous, as free expression of controversial political or religious views was not welcomed in his era. Instead of being openly polemic, he has therefore embedded his work with signs, and leaves it up to us, the viewers, to interpret them for ourselves ■

© Philip McCouat 2019, 2021. First published October 2019.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Lost in Translation: Bruegel’s Tower of Babel”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

For other articles on Bruegel in this Journal, see:

Perception and Blindness in the 16th Century: Pieter Bruegel’s ‘The Blind leading the Blind’

The Emergence of the Winter Landscape: Bruegel and his Predecessors

“All Life is Here”: Bruegel’s ‘Way to Calvary’

Bruegel’s ‘Icarus’ and the Perils of Flight

Bruegel's Peasant Wedding Feast: the case of the missing bridegroom and other mysteries

Bruegel's White Christmas: The Census at Bethlehem

Return to HOME

End Notes

1. Holy Bible, Genesis 11:9; Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, chapter “The Antwerp Building Boom”, What Great Paintings Say. Vol 1, Taschen, Cologne, 2003 at 158.

2. Genesis 11:4.

3. The name is evidently based on a Hebrew word for confusion. The English word “babble” is often assumed to have a similar derivation, but the evidence for this is lacking.

4. Hagen, op cit at 162.

5. Quoted in Justin Marozzi, “Lost cities #1: Babylon – how war almost erased ‘mankind’s greatest heritage site” The Guardian (Australian edn), 8 August 2016 (accessed October 2019)

6. Hagen, op cit at 162.

7. Alexander Wied, Bruegel, English edn, Bay Books, Sydney 1980 at 120.

8. Wied, ibid.

9. The other version, undated, unsigned and smaller, is at Rotterdam, at Museum Boijmans van Beuningen. That version shows a more ordered Tower, but lacks the vignette of the visiting dignitary: see the entry for the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen.

10. This rocky outcrop is reminiscent of Bruegel’s Way to Calvary: see our article here.

11. See end note 29.

12. Once described by St Augustine “that other Babylon of the west”: quoted in Vytas Narusevicius, “The labours of translation: towards Utopia in Bruegel’s Tower of Babel”, Wreck, volume 4, number 1 (2013) 30.

13. Wied, op cit at 120.

14. S. A. Mansbach, “Pieter Bruegel's Towers of Babel”, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte Vol 45 no 1 (1982) 43, at 44.

15. A similar defecating figure appears in Bruegel’s The Magpie on the Gallows, and possibly in his Fall of Icarus: see Robert L Bonn, Painting Life: The Art of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Chaucer Press Books, New York, 2006, page xiv; and our article on Bruegel’s Fall of Icarus.

16. Timothy Foote et al, The World of Bruegel, Time-Life International, The Netherlands, 1971, at 95.

17. Hagen, op cit at 160.

18. Vasco da Gama, 1498.

19. Columbus, 1492.

20. Hagen, op cit at 160.

21. The Duke was the governor of the Netherlands. Extract quoted in Barbara A. Kaminska, “Come, let us make a city and a tower: Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Tower of Babel and the Creation of a Harmonious Community in Antwerp”, Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, Vol 6, issue 2 (Summer 2014).

22. Mansbach, op cit at 46. On Bruegel’s religious beliefs, see also Jürgen Muller and Thomas Schauerte, Pieter Bruegel: The Complete Works, Taschen, Cologne, 2018 at 18.

23. Matthew 16:18, where Jesus says, “it is upon this rock that I will build my church”.

24. Kaminska, op cit.

25. Kaminska, op cit.

26. Narusevicius, op cit at 37.

27. A very similar crane actually operated on the Antwerp waterfront: Hagen, op cit at 161.

28. Bruegel’s evident expertise in depicting construction methods was presumably a factor in his late being commissioned to depict the stages in the building of the Antwerp-Brussels Canal. He died before this could be finished. See generally H. Arthur Klein, “Pieter Bruegel the Elder as a Guide to 16th-Century Technology”, Scientific American, Vol. 238, No. 3 (March 1978), pp. 134-141.

29. Wied, op cit at 124 attributes it to an optical illusion.

30. Wied, op cit at 124.

31. Foote, op cit at 96.

32. Philippe and Françoise Roberts-Jones, Bruegel, Flammarion, Paris 2012, at 249.

© Philip McCouat 2019, 2021. First published October 2019.

Return to HOME

2. Genesis 11:4.

3. The name is evidently based on a Hebrew word for confusion. The English word “babble” is often assumed to have a similar derivation, but the evidence for this is lacking.

4. Hagen, op cit at 162.

5. Quoted in Justin Marozzi, “Lost cities #1: Babylon – how war almost erased ‘mankind’s greatest heritage site” The Guardian (Australian edn), 8 August 2016 (accessed October 2019)

6. Hagen, op cit at 162.

7. Alexander Wied, Bruegel, English edn, Bay Books, Sydney 1980 at 120.

8. Wied, ibid.

9. The other version, undated, unsigned and smaller, is at Rotterdam, at Museum Boijmans van Beuningen. That version shows a more ordered Tower, but lacks the vignette of the visiting dignitary: see the entry for the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen.

10. This rocky outcrop is reminiscent of Bruegel’s Way to Calvary: see our article here.

11. See end note 29.

12. Once described by St Augustine “that other Babylon of the west”: quoted in Vytas Narusevicius, “The labours of translation: towards Utopia in Bruegel’s Tower of Babel”, Wreck, volume 4, number 1 (2013) 30.

13. Wied, op cit at 120.

14. S. A. Mansbach, “Pieter Bruegel's Towers of Babel”, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte Vol 45 no 1 (1982) 43, at 44.

15. A similar defecating figure appears in Bruegel’s The Magpie on the Gallows, and possibly in his Fall of Icarus: see Robert L Bonn, Painting Life: The Art of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Chaucer Press Books, New York, 2006, page xiv; and our article on Bruegel’s Fall of Icarus.

16. Timothy Foote et al, The World of Bruegel, Time-Life International, The Netherlands, 1971, at 95.

17. Hagen, op cit at 160.

18. Vasco da Gama, 1498.

19. Columbus, 1492.

20. Hagen, op cit at 160.

21. The Duke was the governor of the Netherlands. Extract quoted in Barbara A. Kaminska, “Come, let us make a city and a tower: Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Tower of Babel and the Creation of a Harmonious Community in Antwerp”, Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, Vol 6, issue 2 (Summer 2014).

22. Mansbach, op cit at 46. On Bruegel’s religious beliefs, see also Jürgen Muller and Thomas Schauerte, Pieter Bruegel: The Complete Works, Taschen, Cologne, 2018 at 18.

23. Matthew 16:18, where Jesus says, “it is upon this rock that I will build my church”.

24. Kaminska, op cit.

25. Kaminska, op cit.

26. Narusevicius, op cit at 37.

27. A very similar crane actually operated on the Antwerp waterfront: Hagen, op cit at 161.

28. Bruegel’s evident expertise in depicting construction methods was presumably a factor in his late being commissioned to depict the stages in the building of the Antwerp-Brussels Canal. He died before this could be finished. See generally H. Arthur Klein, “Pieter Bruegel the Elder as a Guide to 16th-Century Technology”, Scientific American, Vol. 238, No. 3 (March 1978), pp. 134-141.

29. Wied, op cit at 124 attributes it to an optical illusion.

30. Wied, op cit at 124.

31. Foote, op cit at 96.

32. Philippe and Françoise Roberts-Jones, Bruegel, Flammarion, Paris 2012, at 249.

© Philip McCouat 2019, 2021. First published October 2019.

Return to HOME