Science becomes art

How Joseph Wright’s paintings of scientific experiments exploited brilliant light to depict a new type of knowledge ( and what a “freeborn mouse” thought about it all).

an aversion to darkness

Psychologically, the dark night is our “oldest and most haunting terror” [1]. It brings with it the cold, the unknown and the dangerous. It provides cover for devils and witches, burglars and footpads, ghosts and monsters, sins and pestilences. It is the shadow of death, the harbinger of calamity, the colour of blindness. It is the haven of vermin and parasites, the concealer of hazards, the most likely time to die.

Religion, too, has reinforced and contributed to this common dread, with a remarkably sharp and constantly stressed division between the merits of light and dark. In Christian belief, for example, God is seen as the source of light, while Satan is feared as the prince of darkness. From the beginning of time, it was God that created the light out of darkness and, when he saw the light, he “found it good”. Jesus was the “Light of the World” – those that follow him were assured that they “will not walk in the darkness, but will have the light which is life”; and their eyes will be opened “so that they may turn from darkness to light and from the dominion of Satan to God”. Darkness itself was likened to “the way of the wicked” and the setting for “unfruitful deeds”; and sinners were urged to “lay aside the deeds of darkness and put on the armour of light” [2].

Religion, too, has reinforced and contributed to this common dread, with a remarkably sharp and constantly stressed division between the merits of light and dark. In Christian belief, for example, God is seen as the source of light, while Satan is feared as the prince of darkness. From the beginning of time, it was God that created the light out of darkness and, when he saw the light, he “found it good”. Jesus was the “Light of the World” – those that follow him were assured that they “will not walk in the darkness, but will have the light which is life”; and their eyes will be opened “so that they may turn from darkness to light and from the dominion of Satan to God”. Darkness itself was likened to “the way of the wicked” and the setting for “unfruitful deeds”; and sinners were urged to “lay aside the deeds of darkness and put on the armour of light” [2].

the problem of depicting nighttime

Despite these negative associations, it remained a fact that many crucial Christian religious scenes, both joyful and horrific, took place at night – the announcement of Christ’s birth to the shepherds, the Bethlehem star, the arrival of the Three Kings, possibly the Nativity itself, Jesus’s ultimate betrayal and arrest, and so on. How then did artists respond to this challenge?

For early medieval painters, even though their subject matter was overwhelmingly religious, the challenge was easily overcome. For these painters, realism, or indeed any significant representations of nature itself, was simply not a priority (see our article on winter landscapes). They therefore did not have to reproduce the impression of darkness at all. Instead, backgrounds or skies were typically painted in gold, representing a holy presence. Their actual appearance could be treated as simply irrelevant.

Even later, as a more naturalistic approach developed, night itself was typically not shown in any convincing manner. For one thing, the effects of darkness were difficult for painters themselves to observe, for the obvious reason that it was dark. Even if this difficulty was overcome, painters struggled to find ways of painting a dark scene so that viewers could see what was going on.

For early medieval painters, even though their subject matter was overwhelmingly religious, the challenge was easily overcome. For these painters, realism, or indeed any significant representations of nature itself, was simply not a priority (see our article on winter landscapes). They therefore did not have to reproduce the impression of darkness at all. Instead, backgrounds or skies were typically painted in gold, representing a holy presence. Their actual appearance could be treated as simply irrelevant.

Even later, as a more naturalistic approach developed, night itself was typically not shown in any convincing manner. For one thing, the effects of darkness were difficult for painters themselves to observe, for the obvious reason that it was dark. Even if this difficulty was overcome, painters struggled to find ways of painting a dark scene so that viewers could see what was going on.

early steps in the dark

Various methods were devised. Instead of depicting darkness directly, artists informed the viewer indirectly, using pictorial clues. So, for example, in Giotto’s Arrest of Christ (c 1304), the artist has made a token effort to darken part of the blue sky, but the only real clues that this is night-time are the flaming torches, together with the viewer’s assumed prior knowledge that this was actually a night-time event (Fig 1) [3].

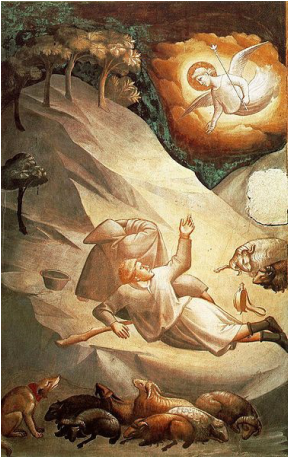

More direct methods were also developed. One attempt to present a more naturalistic night-time setting was by Taddeo Gaddi in his The Angelic Announcement to the Shepherds (c 1328) (Fig 2) [4]. This depicts the biblical scene where an angel appears during the night to tell the shepherds that a Saviour has been born, whereupon “the glory of the Lord shone about them”[5].

Gaddi’s attempt is notable in a number of respects. Firstly, the particular subject matter, with its combination of natural darkness and holy light, enabled Gaddi to use light for a dual function – not only to represent the holy presence, but also to enable the viewer to penetrate the natural darkness of the night. In this way, the light sources become a fundamental part of the composition of the painting, instead of just being incidental props. Gaddi successfully demonstrated that, far from having to avoid or ignore the dark, artists could actually exploit it by contrasting it, unfavourably, to the intensity and pureness of spiritual light.

The second notable aspect of Gaddi’s painting is the extent to which he uses actual observational detail in depicting the scene. He has clearly recognised that darkness drains colour, with consequential differential light effects on the tree trunks and foliage, the shepherds, animals and land contours. Gaddi’s transformation of the shepherds’ faces and clothes, for example, is a striking contrast to the brightly-clad and fresh-faced figures in Giotto’s work [6].

The second notable aspect of Gaddi’s painting is the extent to which he uses actual observational detail in depicting the scene. He has clearly recognised that darkness drains colour, with consequential differential light effects on the tree trunks and foliage, the shepherds, animals and land contours. Gaddi’s transformation of the shepherds’ faces and clothes, for example, is a striking contrast to the brightly-clad and fresh-faced figures in Giotto’s work [6].

Realistic night emerges

Some 80 years later, there would be a further development, in the Limbourg Brothers’ Arrest (Fig 3 c 1416), an illustration from the Book of Hours known as Les Très Riches Heures of the Duc du Berry (see also our article on winter landscapes). This small work depicts the betrayed Jesus in the nighttime Garden of Gethsemane, with the soldiers who have come to arrest him shrinking back and falling to the ground when he reveals his identity [7]. Here at last we have a convincing depiction of darkness [8]. The Limbourgs have used three sources of light – the central brightness of Jesus’ aureole, the torches and lantern (as mentioned in the biblical account) and even the pinprick stars, studding the almost palpable darkness of the deep blue sky. These stars are of course just randomly scattered ~ for a realistic depiction of the actual distribution of stars in the night sky, we would have to wait until Elsheimer's Flight into Egypt (1609).

As time went by, painters restricted themselves less and less to religious subject matter. The “real” world became increasingly their domain, and depictions of natural phenomena such as night became more commonplace. In addition, further artistic refinements were added. Caravaggio (1571-1610), for example, avoided the problems of painting outside in the dark, and at the same time heightened the elements of intensity and drama [9], by posing models (or even mannekins) in a studio and arranging them with light sources to as to achieve the most dramatic effect. Georges de la Tour (1593-1652) also used darkened indoor scenes with highly focused light sources to create images that were almost hyper-realistic (Fig 4).

During the 18th century, however, one artist began to use light in an entirely different way, or rather, to express an entirely different idea.

Joseph Wright and the Lunar Society

The British artist Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797) had always been fascinated by the dramatic effects of chiaroscuro, the effects that can be achieved through the contrast between light and dark. At the same time, he was absorbed in the newly emerging ideas of the “natural philosophers” – those whom we would now called scientists [10] – who were revolutionising our knowledge of how the natural world worked. He also became vitally interested in the works of the industrialists who made use of this knowledge to create new methods of manufacture in advancing the British industrial revolution.

Wright associated himself with men such as Josiah Wedgwood (of Wedgwood pottery fame), Richard Arkwright (cotton production), Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles Darwin, and Wright’s own doctor), and other members of the Birmingham “Lunar Society”, an informal group of like-minded men who met to discuss that latest inventions, ideas and experiments. Others in the group included leading thinkers such as James Watt (steam engines), John Whitehurst (geology), and Joseph Priestley, the chemist who isolated oxygen [11]. Together, with their demonstration of experiments and discussion of the latest developments in chemistry, medicine, electricity and industry, they formed what Jenny Uglow calls a “powerhouse of invention” -- the embodiment of the European movement known as the Enlightenment, whose developments in scientific, religious, intellectual and literary thought transformed people's view of themselves and their place in the natural order [12].

Joseph Wright became the Society's artistic partner, the first painter to express the spirit of the secular new scientific and industrial age, while at the same time being a painter of light [13]. This unusual combination of interests led him to present both natural and artificial light in contexts as diverse as the “cold light of the moon mingled with dim candlelight…dark trees silhouetted against a blazing furnaces and a star-lit sky; the glare of molten glass or red-hot iron in gloomy workshops; [and] the flaming pottery ovens at Etruria” [14].

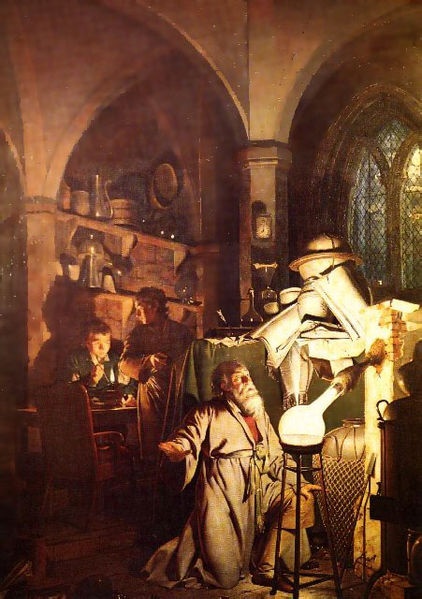

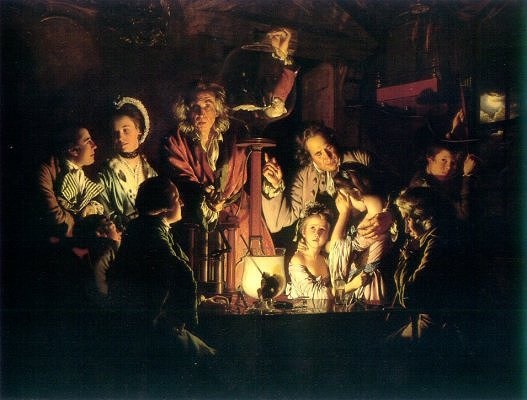

But perhaps Wright’s most notable achievements, or at least those which concern us most here, were three paintings, exhibited over a five year period, which concerned scientific (or pseudo-scientific) experimentation. This was a topic that had only rarely been treated seriously in art [15], and the striking specificity of the titles gives a clue to their distinctiveness and precision – The Alchymist, in Search of the Philosopher's Stone, Discovers Phosphorus, and prays for the successful Conclusion of his operation, as was the custom of the Ancient Chymical Astrologers (1771); A Philosopher giving that Lecture on the Orrery, in which a Lamp is put in the Place of the Sun (1766); and An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768). The latter two paintings are huge, ranging from three to four square metres, a size more readily associated with history paintings, suggesting that the artist intended that their subject matter be regarded as worthy of serious consideration.

Wright associated himself with men such as Josiah Wedgwood (of Wedgwood pottery fame), Richard Arkwright (cotton production), Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles Darwin, and Wright’s own doctor), and other members of the Birmingham “Lunar Society”, an informal group of like-minded men who met to discuss that latest inventions, ideas and experiments. Others in the group included leading thinkers such as James Watt (steam engines), John Whitehurst (geology), and Joseph Priestley, the chemist who isolated oxygen [11]. Together, with their demonstration of experiments and discussion of the latest developments in chemistry, medicine, electricity and industry, they formed what Jenny Uglow calls a “powerhouse of invention” -- the embodiment of the European movement known as the Enlightenment, whose developments in scientific, religious, intellectual and literary thought transformed people's view of themselves and their place in the natural order [12].

Joseph Wright became the Society's artistic partner, the first painter to express the spirit of the secular new scientific and industrial age, while at the same time being a painter of light [13]. This unusual combination of interests led him to present both natural and artificial light in contexts as diverse as the “cold light of the moon mingled with dim candlelight…dark trees silhouetted against a blazing furnaces and a star-lit sky; the glare of molten glass or red-hot iron in gloomy workshops; [and] the flaming pottery ovens at Etruria” [14].

But perhaps Wright’s most notable achievements, or at least those which concern us most here, were three paintings, exhibited over a five year period, which concerned scientific (or pseudo-scientific) experimentation. This was a topic that had only rarely been treated seriously in art [15], and the striking specificity of the titles gives a clue to their distinctiveness and precision – The Alchymist, in Search of the Philosopher's Stone, Discovers Phosphorus, and prays for the successful Conclusion of his operation, as was the custom of the Ancient Chymical Astrologers (1771); A Philosopher giving that Lecture on the Orrery, in which a Lamp is put in the Place of the Sun (1766); and An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768). The latter two paintings are huge, ranging from three to four square metres, a size more readily associated with history paintings, suggesting that the artist intended that their subject matter be regarded as worthy of serious consideration.

the Alchymist: Accidental or “miraculous” enlightenment

The Alchymist depicts the chance discovery of the element phosphorus by an alchemist searching for the “philosopher’s stone”, the legendary substance that alchemists believed was capable of turning base metals into gold or silver [16]. The painting is complex and invites contradictory interpretations, mainly because its focus is so uncertain. So, for example, while it depicts a science-related topic, it also has significant religious overtones – the alchemist is shown kneeling in prayer, almost saint-like, before the brilliant light of the burning phosphorus (also known as the “Devil’s element”), in what appears to be a church [17]. Is the alchemist’s discovery intended to be viewed as a triumph of experimentation over faith? Or is this undermined by the fact that the discovery was accidental?

Further complicating the issue is that fact that the painting seems to occupy multiple time zones: the actual action depicted took place in the 17th century, yet the alchemist is in classical robes, the assistant is in 18th dress, the architectural setting is gothic, and the experimental equipment is comparable to that used by members of the Lunar Society in 1770. Added to this is the presence of multiple sources of light – the cool moonlight, the warm candlelight and the white-hot phosphorus. Is the light generated by the discovery in the foreground intended to be seen as taking over from the light of faith, represented by the moonlight shining faintly through the church window in the background?

However these views may ultimately be resolved, Wright appears to be using light to highlight an uneasy transition between matters of faith (the praying, the church), myth (the theories of alchemy) and knowledge (the discovery, albeit accidental, of phosphorus).

However these views may ultimately be resolved, Wright appears to be using light to highlight an uneasy transition between matters of faith (the praying, the church), myth (the theories of alchemy) and knowledge (the discovery, albeit accidental, of phosphorus).

Rational enlightenment

The other two paintings depict a more contemporary and purely scientific subject, treating it entirely seriously, and with no suggestion of the quackery or fantasy which had characterised some artists’ earlier representations. In both works, intense light focuses on the essentials that Wright wishes to highlight – the commanding central presence of the “philosopher”, and the awed expressions of the onlookers, adding to the atmosphere of wonder.

The Orrery was possibly based on a series of lectures which had recently been held by the Scot James Ferguson in Wright’s home town of Derby [18]. It depicts an impressive red-cloaked natural philosopher demonstrating the operation of an “orrery”, a sophisticated mechanical device which used cranks, levers and curved metal bands to mimic the motions of the planets around the sun – a task only possible because of Isaac Newton’s challenging demonstration that these orbits were mathematically predictable [19].

The spectators, all totally absorbed, include a man on the left taking notes (this is probably based on Wright’s friend Peter Perez Burdett, a cartographer and surveyor} and two others on the right. The presence of a women at far left and the rapt children suggests that this is a private lecture, possibly in a domestic library. The scene is brilliantly from an unseen source, masked by the darkened figure in the foreground leaning away from us over the orrery. Despite its brilliance, the light is unrealistically localised so the rest of the room is shrouded in almost impenetrable darkness. Paradoxically, at first glance, the painting recalls a Nativity scene [20], with the orrery resembling a crib-like structure, and the awe-struck spectators, including cherub-like children, clustered round the brilliantly-lit magical apparition that is presented to them.

The spectators, all totally absorbed, include a man on the left taking notes (this is probably based on Wright’s friend Peter Perez Burdett, a cartographer and surveyor} and two others on the right. The presence of a women at far left and the rapt children suggests that this is a private lecture, possibly in a domestic library. The scene is brilliantly from an unseen source, masked by the darkened figure in the foreground leaning away from us over the orrery. Despite its brilliance, the light is unrealistically localised so the rest of the room is shrouded in almost impenetrable darkness. Paradoxically, at first glance, the painting recalls a Nativity scene [20], with the orrery resembling a crib-like structure, and the awe-struck spectators, including cherub-like children, clustered round the brilliantly-lit magical apparition that is presented to them.

Turning to the Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (Fig 7), this depicts the type of experiment which Lunar Society member Joseph Priestley had been carrying out, involving the placement of a small animal such as a bird or mouse in an air pump (also known as a vacuum pump), from which the air was progressively withdrawn, in an attempt to demonstrate that oxygen (or “dephlogisticated air” as Priestley called it) was essential for life [21].

Again, a centrally-placed red-cloaked natural philosopher commands our attention in a brilliantly lit domestic room [22], before an intimate circle of family and friends. However, the mood of this painting is quite different from the Orrery. Rather than a sober philosopher and a feeling of calmness and awe, there is a more dramatic and theatrical feel. Instead of being magisterial, the philosopher is somewhat wild-eyed, possibly because he is more showman than experimenter. The bird is a white cockatoo, a rather spectacular species, which would not normally be risked in such an experiment. And instead of rapt attention, some in the audience can be seen to be expressing considerable concern at what is going on. A young girl looks pityingly upwards at the trapped fluttering cockatoo, and clutches at her sister who is turning her head away in apparent fear or revulsion. The couple at left appear to be sharing rather mixed reviews of the spectacle (or possibly just have eyes for each other).

The details of the experiment in this painting, like the demonstration of the orrery,were possibly based on James Ferguson's lectures. However, it is significant that the dramatic version Wright chooses to depict was one described by Ferguson as "too shocking to every spectator who has the least degree of humanity", where it culminates in the expiry of a living animal "in all the agonies of a most bitter and cruel death" [22a]. In Wright's painting, however, the possibility of the bird being reprieved at the last moment is tantalisingly left open.

As in the Orrery, the exact nature of the light source is not clear: It seems too brilliant to be just the candle which we can see partly obscured behind the big glass bowl on the table (Egerton, op cit at 54), though it has been suggested that the bowl could contain burning sulphur [23], with the dark object in the bowl being a human skull (signifying death) or possibly even human lungs. The question may in any event be largely academic, as Wright was not necessarily intending to depict naturalistic light sources in these paintings. Like the Dutch candlelight painters such as Schalken before him (and Caravaggio before that), Wright created the lighting effects in his scenes artificially. He invented a contrivance of panelled scenes in the corner of his studio behind which he could pose his subjects in the dark. By opening one panel and then another, he could study them from different angles [24].

Again, a centrally-placed red-cloaked natural philosopher commands our attention in a brilliantly lit domestic room [22], before an intimate circle of family and friends. However, the mood of this painting is quite different from the Orrery. Rather than a sober philosopher and a feeling of calmness and awe, there is a more dramatic and theatrical feel. Instead of being magisterial, the philosopher is somewhat wild-eyed, possibly because he is more showman than experimenter. The bird is a white cockatoo, a rather spectacular species, which would not normally be risked in such an experiment. And instead of rapt attention, some in the audience can be seen to be expressing considerable concern at what is going on. A young girl looks pityingly upwards at the trapped fluttering cockatoo, and clutches at her sister who is turning her head away in apparent fear or revulsion. The couple at left appear to be sharing rather mixed reviews of the spectacle (or possibly just have eyes for each other).

The details of the experiment in this painting, like the demonstration of the orrery,were possibly based on James Ferguson's lectures. However, it is significant that the dramatic version Wright chooses to depict was one described by Ferguson as "too shocking to every spectator who has the least degree of humanity", where it culminates in the expiry of a living animal "in all the agonies of a most bitter and cruel death" [22a]. In Wright's painting, however, the possibility of the bird being reprieved at the last moment is tantalisingly left open.

As in the Orrery, the exact nature of the light source is not clear: It seems too brilliant to be just the candle which we can see partly obscured behind the big glass bowl on the table (Egerton, op cit at 54), though it has been suggested that the bowl could contain burning sulphur [23], with the dark object in the bowl being a human skull (signifying death) or possibly even human lungs. The question may in any event be largely academic, as Wright was not necessarily intending to depict naturalistic light sources in these paintings. Like the Dutch candlelight painters such as Schalken before him (and Caravaggio before that), Wright created the lighting effects in his scenes artificially. He invented a contrivance of panelled scenes in the corner of his studio behind which he could pose his subjects in the dark. By opening one panel and then another, he could study them from different angles [24].

Anna Barbauld and the Mouse’s Petition

As evidenced by the negative reactions of some of the witnesses, the Air Pump experiment raised some ethical or moral issues not present in the other paintings. Those issues concerned the extent to which the interests of the experimental subject – in this case the bird which is being deliberately deprived of oxygen – should be taken into account.

The issue of animal rights is one which still remains unresolved today in western society. Traditional Christian belief clearly placed humans as having dominion “over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” [25]. At the same time, it opposed needless cruelty, as in the incident where the angel asks the soothsayer Balaam, “Why have you struck your donkey these three times? Behold, I have come out to oppose you because your way is perverse before me” [26].

Wright presents the issue by reference only to the reactions of the women and children (presumably sentimental pity was not considered appropriate for men). Other than the general indication of fluttering, the reaction of the bird itself is not clearly presented.The implications for the experimental “victim” were, however, to be raised squarely, in a striking manner, and from a surprising source. This source was Anna Laetitia Barbauld (1743-1825), one of a rare breed, a prominent female intellectual, critic, teacher, writer and poet of the late Enlightenment years of the late 18th century [27]. She had an active and lively interest in nature, politics, male/female relationships, children, animals and – crucially for our purposes – in the scientific developments that marked that age [28].

The issue of animal rights is one which still remains unresolved today in western society. Traditional Christian belief clearly placed humans as having dominion “over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” [25]. At the same time, it opposed needless cruelty, as in the incident where the angel asks the soothsayer Balaam, “Why have you struck your donkey these three times? Behold, I have come out to oppose you because your way is perverse before me” [26].

Wright presents the issue by reference only to the reactions of the women and children (presumably sentimental pity was not considered appropriate for men). Other than the general indication of fluttering, the reaction of the bird itself is not clearly presented.The implications for the experimental “victim” were, however, to be raised squarely, in a striking manner, and from a surprising source. This source was Anna Laetitia Barbauld (1743-1825), one of a rare breed, a prominent female intellectual, critic, teacher, writer and poet of the late Enlightenment years of the late 18th century [27]. She had an active and lively interest in nature, politics, male/female relationships, children, animals and – crucially for our purposes – in the scientific developments that marked that age [28].

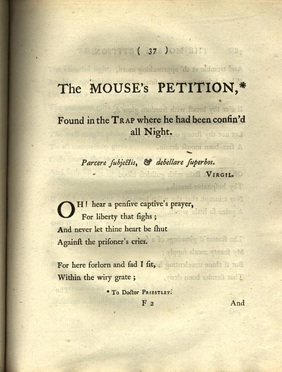

One evening, while visiting her friend Priestley’s home, Barbauld wrote a poem, The Mouse’s Petition to Dr Priestley, Found in the Trap where he had been Contained all Night 1773. To drive the point home, she left this “Petition” in the cage of a mouse who was due to be experimented upon the next morning [29].

Barbauld’s poem was intended, not directly as an accusation of cruelty by her friend Priestley, but rather as a reminder to him of the requirement for humanity in the treatment of animals – “nature’s commoners”, as Barbauld described them. Most unusually for this era, the poem places the reader in the plaintive position of the caged but “freeborn mouse” who somehow knows its ghastly fate. The sentiments it expresses would apply equally to the captive bird in Wright’s painting:

Barbauld’s poem was intended, not directly as an accusation of cruelty by her friend Priestley, but rather as a reminder to him of the requirement for humanity in the treatment of animals – “nature’s commoners”, as Barbauld described them. Most unusually for this era, the poem places the reader in the plaintive position of the caged but “freeborn mouse” who somehow knows its ghastly fate. The sentiments it expresses would apply equally to the captive bird in Wright’s painting:

Oh, hear a pensive captive's prayer / For liberty that sighs / And never let thine heart be shut / Against the wretch’s cries!

For here forlorn and sad I sit / Within the wiry grate / And tremble at th' approaching morn /Which brings impending fate.

If e'er thy breast with freedom glow'd / And spurn'd a tyrant's chain / Let not thy strong oppressive force /A free-born mouse detain!

O, do not stain with guiltless blood / Thy hospitable hearth! / Nor triumph that thy wiles betray'd /A prize so little worth.

Barbauld reminds Priestley that all heaven’s creatures are entitled to the “well taught” philosopher’s consideration, tenderness and compassion:

The cheerful light, the vital air /Are blessings widely given / Let nature's commoners enjoy /The common gifts of heaven.

The well taught philosophic mind /To all compassion gives / Casts round the world an equal eye / And feels for all that lives…..

…Beware, lest in the worm you crush /A brother's soul you find / And tremble lest thy luckless hand / Dislodge a kindred mind.

Apparently, the mouse’s plea was effective. It is reported that Priestley, who himself had harboured reservations about the possible inhumanity of some types of experimentation, let the mouse go [30]. With the benefit of hindsight, it has been suggested that the Mouse’s Petition is “perhaps the first animal rights manifesto ever written”[31]. Certainly, almost 250 years after it was written, it remains a surprisingly affecting plea that the searching light of scientific thinking be tempered by ethical considerations, and as an incidental reminder that while the scientific method may lead to intellectual knowledge, poetry can provide its own level of emotional insight.

For here forlorn and sad I sit / Within the wiry grate / And tremble at th' approaching morn /Which brings impending fate.

If e'er thy breast with freedom glow'd / And spurn'd a tyrant's chain / Let not thy strong oppressive force /A free-born mouse detain!

O, do not stain with guiltless blood / Thy hospitable hearth! / Nor triumph that thy wiles betray'd /A prize so little worth.

Barbauld reminds Priestley that all heaven’s creatures are entitled to the “well taught” philosopher’s consideration, tenderness and compassion:

The cheerful light, the vital air /Are blessings widely given / Let nature's commoners enjoy /The common gifts of heaven.

The well taught philosophic mind /To all compassion gives / Casts round the world an equal eye / And feels for all that lives…..

…Beware, lest in the worm you crush /A brother's soul you find / And tremble lest thy luckless hand / Dislodge a kindred mind.

Apparently, the mouse’s plea was effective. It is reported that Priestley, who himself had harboured reservations about the possible inhumanity of some types of experimentation, let the mouse go [30]. With the benefit of hindsight, it has been suggested that the Mouse’s Petition is “perhaps the first animal rights manifesto ever written”[31]. Certainly, almost 250 years after it was written, it remains a surprisingly affecting plea that the searching light of scientific thinking be tempered by ethical considerations, and as an incidental reminder that while the scientific method may lead to intellectual knowledge, poetry can provide its own level of emotional insight.

A new light in the darkness

The paintings we have discussed are complex, and may be subject to many interpretations. In each case, however, it seems to have been generally accepted that Wright is using brilliant light to express a novel concept. It is not divine light, as presented by medieval painters, nor is it merely the physical light of nature. Rather, as the expression “Age of Enlightenment” suggests, it can be interpreted as the light of reasoned knowledge, overpowering the surrounding darkness of superstition [32].

Given Wright’s interests and associations, this interpretation makes some sense. However, it also needs to be observed that the nature of that knowledge seems to shift in each painting. It is suggested that this is because each painting represents a different stage in the development of scientific thought. The Alchymist represents the first of those stages [33]. It shows a fortuitous discovery being made through alchemical means, an approach which, though largely non-scientific, was probably a necessary step in the development of the scientific approach. The painting’s mixture of scientific and religious motifs reflects the fact that the knowledge it depicts has been seemingly-miraculously acquired, rather than scientifically derived.

The second stage, represented by The Orrery, can be viewed as depicting the triumph of methodical, rational science over ignorance or myth. The third stage, represented by The Air Pump, can be interpreted as raising some possible reservations about the lengths to which scientific experimentation can be taken. This painting appears to raise the question of whether strict rationality may need to be softened by moral or ethical considerations – a question which still resonates strongly today.

© Philip McCouat 2015, 2018

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Science becomes Art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy The emergence of the winter landscape

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

Given Wright’s interests and associations, this interpretation makes some sense. However, it also needs to be observed that the nature of that knowledge seems to shift in each painting. It is suggested that this is because each painting represents a different stage in the development of scientific thought. The Alchymist represents the first of those stages [33]. It shows a fortuitous discovery being made through alchemical means, an approach which, though largely non-scientific, was probably a necessary step in the development of the scientific approach. The painting’s mixture of scientific and religious motifs reflects the fact that the knowledge it depicts has been seemingly-miraculously acquired, rather than scientifically derived.

The second stage, represented by The Orrery, can be viewed as depicting the triumph of methodical, rational science over ignorance or myth. The third stage, represented by The Air Pump, can be interpreted as raising some possible reservations about the lengths to which scientific experimentation can be taken. This painting appears to raise the question of whether strict rationality may need to be softened by moral or ethical considerations – a question which still resonates strongly today.

© Philip McCouat 2015, 2018

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Science becomes Art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy The emergence of the winter landscape

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

end notes

[1] For a detailed history of nighttime, “the forgotten half of history”, see A Roger Ekirch, At Day’s Close: A History of Nighttime, Weidenfield & Nicholson, London, 2005.

[2] “found it good”: Gen 1:4; “light which is life”: John 8:12; “Satan to God”: Acts 26:18; “wicked”: Prov 4:19; “unfruitful”: Ephesians 5:11; “armour of light”: Romans 13:12.

[3] Another typical clue in some paintings was the inclusion of a sleeping person.

[4] See Florian Heine, “The First Painting of a Nighttime Scene”, The First Time: Innovations in Art, Bucher, Munich 2007, at 22-27.

[5] Luke 2 v 8-9.

[6] Heine, op cit.

[7] John 18:6.

[8] Heine, op cit at 26. Gentile da Fabriano's Nativity predella panel from the Stozzi Altarpiece (1423) is also a notable nighttime scene, though with no attempt to portray the sky accurately. For another early realistic example, see Geertgen tot Sint Jans The Nativity at Night (1490)'.

[9] Waldemar Januszcak, “Great painters brought night to the nativity”, The Sunday Times, 23/12/2010, accessed at http://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/great-painters-brought-night-to-the-nativity/story-e6frg8n6-1225975159027

[10] The word “scientist” was not used until 1834.

[11] The Lunar Society was so-named because it met monthly on the Monday nearest the full moon: Jenny Uglow, The Lunar Men, Faber and Faber, London, 2002, at xiii.

[12] Uglow, op cit at xiv; see also Benedict Nicolson, Joseph Wright of Derby, Painter of Light, Pantheon, 1968, and David Fraser, "Joseph Wright of Derby and the Lunar Society", in Judy Egerton, Wright of Derby (Exh Cat), Tate Gallery, London 1990 at 15-24..

[13] Francis D Klingender, Art and the Industrial Revolution, Paladin, London, 1968, at 46 ff.

[14] Klingender, op cit.

[15] A notable exception is provided by Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp (1631).

[16] This was probably Hennig Brand, in 1669: see generally Janet Vertesi, “Light and Enlightenment in Joseph Wright of Derby’s The Alchymist”, Paper delivered at Romanticism and the Midlands Enlightenment Conference, Birmingham, UK, July 3, 2004.

[17] Wright’s The Blacksmith’s Shop 1771 also appears to be set in the interior of a church.

[18] Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, “A star machine explains the heavens”, What Great Paintings Say, Vol 1, Taschen, Cologne, 2003, Vol 1 at 327.

[19] The machine gets its name from the Earl of Orrery, who commissioned the original construction in the early 18th century: Hagen, op cit.The philosopher in the painting actually rather resembles the real life Newton (see Egerton, op cit at 54)..

[20] A similar comment could be made about Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson]: see note 15.

[21] Richard Holmes, The Age of Wonder, Harper Press, London, 2008, at 303.

[22] As in the Alchymist, the unnatural brilliance of the light source is underlined by the contrast with the natural light of the pale moon shown through the window on the right.

[22a] Fraser, op cit at 19.

[23] David Hockney, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters. New York, Studio Books, 2001, at 129.

[24] Klingender, op cit at 46-7.

[25] Gen 1:26-28.

[26] Numbers 22:32.

[27] See generally William McCarthy, Anna Letitia Barbauld: Voice of the Enlightenment, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 2008.

[28] After a long period of neglect, Babauld’s extraordinary life and achievements have been rediscovered in recent years. In general, the extent of female involvement in intellectual life during this period has often been overlooked: Hagen, op cit at 330. In France, for example, the mathematician the Marquise du Chatelet translated Newton’s works into French: see David Bodanis, Passionate Minds: The Great Enlightenment Love Affair, Little Brown, London, 2006.

[29] Mary Ellen Bellanca, “Science, Animal Sympathy, and Anna Barbauld’s ‘the Mouse’s Petition’.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 37.1 (2003): 47-67.

[30] Bellanca, op cit.

[31] Holmes, op cit at 303.

[32] Vertesi, op cit. Science was also described as "the light of truth" in Akenside's poem Hymn to Science (1744).

[33] Though it was actually painted last of the three paintings being discussed.

© Philip McCouat 2015, 2018

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Science becomes Art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy The emergence of the winter landscape

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

[2] “found it good”: Gen 1:4; “light which is life”: John 8:12; “Satan to God”: Acts 26:18; “wicked”: Prov 4:19; “unfruitful”: Ephesians 5:11; “armour of light”: Romans 13:12.

[3] Another typical clue in some paintings was the inclusion of a sleeping person.

[4] See Florian Heine, “The First Painting of a Nighttime Scene”, The First Time: Innovations in Art, Bucher, Munich 2007, at 22-27.

[5] Luke 2 v 8-9.

[6] Heine, op cit.

[7] John 18:6.

[8] Heine, op cit at 26. Gentile da Fabriano's Nativity predella panel from the Stozzi Altarpiece (1423) is also a notable nighttime scene, though with no attempt to portray the sky accurately. For another early realistic example, see Geertgen tot Sint Jans The Nativity at Night (1490)'.

[9] Waldemar Januszcak, “Great painters brought night to the nativity”, The Sunday Times, 23/12/2010, accessed at http://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/great-painters-brought-night-to-the-nativity/story-e6frg8n6-1225975159027

[10] The word “scientist” was not used until 1834.

[11] The Lunar Society was so-named because it met monthly on the Monday nearest the full moon: Jenny Uglow, The Lunar Men, Faber and Faber, London, 2002, at xiii.

[12] Uglow, op cit at xiv; see also Benedict Nicolson, Joseph Wright of Derby, Painter of Light, Pantheon, 1968, and David Fraser, "Joseph Wright of Derby and the Lunar Society", in Judy Egerton, Wright of Derby (Exh Cat), Tate Gallery, London 1990 at 15-24..

[13] Francis D Klingender, Art and the Industrial Revolution, Paladin, London, 1968, at 46 ff.

[14] Klingender, op cit.

[15] A notable exception is provided by Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp (1631).

[16] This was probably Hennig Brand, in 1669: see generally Janet Vertesi, “Light and Enlightenment in Joseph Wright of Derby’s The Alchymist”, Paper delivered at Romanticism and the Midlands Enlightenment Conference, Birmingham, UK, July 3, 2004.

[17] Wright’s The Blacksmith’s Shop 1771 also appears to be set in the interior of a church.

[18] Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, “A star machine explains the heavens”, What Great Paintings Say, Vol 1, Taschen, Cologne, 2003, Vol 1 at 327.

[19] The machine gets its name from the Earl of Orrery, who commissioned the original construction in the early 18th century: Hagen, op cit.The philosopher in the painting actually rather resembles the real life Newton (see Egerton, op cit at 54)..

[20] A similar comment could be made about Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson]: see note 15.

[21] Richard Holmes, The Age of Wonder, Harper Press, London, 2008, at 303.

[22] As in the Alchymist, the unnatural brilliance of the light source is underlined by the contrast with the natural light of the pale moon shown through the window on the right.

[22a] Fraser, op cit at 19.

[23] David Hockney, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters. New York, Studio Books, 2001, at 129.

[24] Klingender, op cit at 46-7.

[25] Gen 1:26-28.

[26] Numbers 22:32.

[27] See generally William McCarthy, Anna Letitia Barbauld: Voice of the Enlightenment, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 2008.

[28] After a long period of neglect, Babauld’s extraordinary life and achievements have been rediscovered in recent years. In general, the extent of female involvement in intellectual life during this period has often been overlooked: Hagen, op cit at 330. In France, for example, the mathematician the Marquise du Chatelet translated Newton’s works into French: see David Bodanis, Passionate Minds: The Great Enlightenment Love Affair, Little Brown, London, 2006.

[29] Mary Ellen Bellanca, “Science, Animal Sympathy, and Anna Barbauld’s ‘the Mouse’s Petition’.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 37.1 (2003): 47-67.

[30] Bellanca, op cit.

[31] Holmes, op cit at 303.

[32] Vertesi, op cit. Science was also described as "the light of truth" in Akenside's poem Hymn to Science (1744).

[33] Though it was actually painted last of the three paintings being discussed.

© Philip McCouat 2015, 2018

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Science becomes Art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy The emergence of the winter landscape

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME