FORGOTTEN WOMEN ARTISTS

#3 Marie-Gabrielle Capet: Stepping out from the Shadows

By Philip McCouat For reader comments on this article see here

This the third in a series of articles discussing the lives and works of distinguished women artists who are not well-known in modern times. Other articles have dealt with Arcangela Paladini, Jane Loudon and Michaelina Wautier and Thérèse Schwartze

This the third in a series of articles discussing the lives and works of distinguished women artists who are not well-known in modern times. Other articles have dealt with Arcangela Paladini, Jane Loudon and Michaelina Wautier and Thérèse Schwartze

A fortuitous discovery

One wintry Sunday in December 1925, a small painting disappeared from the Museum of Fine Arts at Caen, in north-western France. The painting was not recovered and, as time went by, it was almost forgotten…. but not entirely.

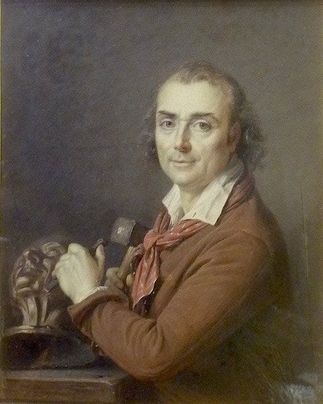

Almost ninety years later, in January 2012, a miniature portrait, painter unknown, and with no reserve price, came up for auction in Paris. A sharp-eyed art lover recognised it as closely resembling the long-missing painting from Caen. The work was promptly withdrawn from sale, and later examination confirmed that it was indeed the lost painting -- a work by an 18th century French artist Marie-Gabrielle Capet, the Portrait of Sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon working at the bust of Voltaire [1]. You can see it now, comprehensively restored, and safely back in its place at the Museum at Caen (Fig 1).

Almost ninety years later, in January 2012, a miniature portrait, painter unknown, and with no reserve price, came up for auction in Paris. A sharp-eyed art lover recognised it as closely resembling the long-missing painting from Caen. The work was promptly withdrawn from sale, and later examination confirmed that it was indeed the lost painting -- a work by an 18th century French artist Marie-Gabrielle Capet, the Portrait of Sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon working at the bust of Voltaire [1]. You can see it now, comprehensively restored, and safely back in its place at the Museum at Caen (Fig 1).

This fortuitous rediscovery, and the subsequent major exhibition of Capet’s surviving works [2], have acted as catalysts for the rehabilitation of her reputation which, like the miniature, had largely been forgotten after her death. In this article, the third in our series of Forgotten Women Artists, we take a closer look at this talented but largely overlooked artist.

A rapid rise from humble beginnings

Marie-Gabrielle Capet was born in Lyon in 1761. She came from humble beginnings, with both parents being servants. Little is known of her childhood, but it seems clear that she demonstrated considerable artistic ability from a very young age – when she first emerges into our view, at age 19, she has already arrived in Paris as an accomplished pastellist.

Marie-Gabrielle had evidently attracted the attention of one of the great ladies of French painting, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, who accepted her as a student in her studio. Marie-Gabrielle soon took precedence over Adélaïde’s numerous other female protégés. There were nine of these in total, collectively referred to as “Les Demoiselles” [3], and they included the talented Marie-Victoire d'Avril and Marie-Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond.

Within a few months, Marie-Gabrielle was exhibiting drawings and pastels at the Salon de la Jeunesse, and later at the Salon de la Correspondence. She began branching out into oils and, with the support of Adélaïde, began to secure commissions from the upper middle class and nobility, ultimately extending even to royalty. Her miniatures would come to form a substantial part of her work.

Marie-Gabrielle had evidently attracted the attention of one of the great ladies of French painting, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, who accepted her as a student in her studio. Marie-Gabrielle soon took precedence over Adélaïde’s numerous other female protégés. There were nine of these in total, collectively referred to as “Les Demoiselles” [3], and they included the talented Marie-Victoire d'Avril and Marie-Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond.

Within a few months, Marie-Gabrielle was exhibiting drawings and pastels at the Salon de la Jeunesse, and later at the Salon de la Correspondence. She began branching out into oils and, with the support of Adélaïde, began to secure commissions from the upper middle class and nobility, ultimately extending even to royalty. Her miniatures would come to form a substantial part of her work.

Clearly, Marie-Gabrielle had come a long way, and quite quickly. Here in fig 4 we can see her, aged 22, in a buoyantly confident self-portrait, demonstrating her skill in oils as well as her favoured pastel. This painting prompted the Journal de Paris to describe her as an artist “who, among the female virtuosos, has the surest touch and drawing” [4].

We can also see her depicted in Adélaïde’s own striking and monumental Self-Portrait with Two Students (1785) (Fig 5). Marie-Gabrielle is leaning forward excitedly, admiring her elaborately-dressed teacher’s work-in-progress. Her fellow student, Marie-Marguerite, is behind, with her arm affectionately around Marie-Gabrielle – at the time, a significant depiction of outward affection by one noble-born to one from humble origins [5].

The role of women artists

During this period, the role of women artists was highly contentious. Indeed, many male commentators were extremely critical of the whole idea of women painting. Their objections typically focused on the relative merits of women’s works, disputing their real authorship (“no mere woman could have done this unaided”) or denigrating the genres, such as miniatures or domestic scenes, to which women were often unwillingly confined. Some of these criticisms also went so far as to impugn the morals or propriety of women who had chosen to go outside social norms by trying to establish independent careers as artists [6].

Marie-Gabrielle was fortunate that her champion, Adélaïde, was one the few women who were generally acknowledged as having a particular eminence. In 1783 Adélaïde had been given the unusual honour of being admitted to the Academy, more formally known as the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, giving her the right to exhibit her work at the Salon. Her admission, along with that of the celebrated Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, filled the Academy’s newly self-imposed quota of admitting no more than four “truly exceptional” female members [7].

In the Academy’s view, this numerical limit on women was “sufficient to honour their talent: women cannot be useful to the progress of the arts because the modesty of their sex forbids them from being able to study after nature [ie male nudes] and in the [Academy]” [8]. These drawbacks, they said, meant that women were not capable of creating what were then considered to be the highest form of painting, the so-called “history” paintings. These were large works in oil or fresco, capturing a moment in a story, with multiple interacting characters, though not necessarily historical. They were commonly regarded as superior to portraits or landscapes, as they required the full range of painterly skills.

Despite (or perhaps because of) these institutional and cultural restrictions, Adélaïde, with her “stable” of women students, was particularly active in promoting the role of women painters. Her Self-Portrait with Two Students (Fig 5 above) was actually submitted to the Salon in 1785 as part of her campaign to establish women’s rightful role as full participants in art, and to set the seal on her own credentials in particular [9]. She also lobbied actively, though initially unsuccessfully, to have the “four females” limit removed, or at least raised. At one stage, she even succeeded in obtaining a court order to destroy libellous pamphlets circulated by an anonymous critic containing lewd gossip about her sexual and professional ethics.

Marie-Gabrielle was fortunate that her champion, Adélaïde, was one the few women who were generally acknowledged as having a particular eminence. In 1783 Adélaïde had been given the unusual honour of being admitted to the Academy, more formally known as the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, giving her the right to exhibit her work at the Salon. Her admission, along with that of the celebrated Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, filled the Academy’s newly self-imposed quota of admitting no more than four “truly exceptional” female members [7].

In the Academy’s view, this numerical limit on women was “sufficient to honour their talent: women cannot be useful to the progress of the arts because the modesty of their sex forbids them from being able to study after nature [ie male nudes] and in the [Academy]” [8]. These drawbacks, they said, meant that women were not capable of creating what were then considered to be the highest form of painting, the so-called “history” paintings. These were large works in oil or fresco, capturing a moment in a story, with multiple interacting characters, though not necessarily historical. They were commonly regarded as superior to portraits or landscapes, as they required the full range of painterly skills.

Despite (or perhaps because of) these institutional and cultural restrictions, Adélaïde, with her “stable” of women students, was particularly active in promoting the role of women painters. Her Self-Portrait with Two Students (Fig 5 above) was actually submitted to the Salon in 1785 as part of her campaign to establish women’s rightful role as full participants in art, and to set the seal on her own credentials in particular [9]. She also lobbied actively, though initially unsuccessfully, to have the “four females” limit removed, or at least raised. At one stage, she even succeeded in obtaining a court order to destroy libellous pamphlets circulated by an anonymous critic containing lewd gossip about her sexual and professional ethics.

A member of an extended artistic family

Over the years, Marie-Gabrielle came to form a close and, in many ways, mutually beneficial relationship with Adélaïde. She was her pupil, her occasional model, her assistant and ultimately, in effect, her surrogate daughter [10]. Marie-Gabrielle never married, and became a permanent part of Adélaïde’s household, living with her throughout that artist’s lifetime (including in her atelier at the Louvre) and continued to live there even after Adélaïde’s marriage to the painter François Vincent. Marie-Gabrielle also came to form a warm daughter-father relationship with François, calling him “père” (father) and continuing to work in his atelier after Adélaïde died [11].

Marie-Gabrielle herself would later capture this long-lasting relationship in The Workshop of Madame Vincent (Fig 6). This painting depicts Adélaïde (Madame Vincent) engaged in painting the artist/senator Joseph-Marie Vien, the teacher of Adélaïde’s husband François, in the company of several friends, pupils and members of the Vien family. Marie-Gabrielle has pictured herself on the left of the canvas, looking directly at the viewer, and holding in her hand Adélaïde’s palette, on which she has just prepared the colours. The scene is like a genealogy of Marie-Gabrielle’s artistic family, with Vien as her artistic “grandfather”, in that he was a teacher of François, who in turn taught Adélaïde, who in turn taught Marie-Gabrielle [12].

Marie-Gabrielle herself would later capture this long-lasting relationship in The Workshop of Madame Vincent (Fig 6). This painting depicts Adélaïde (Madame Vincent) engaged in painting the artist/senator Joseph-Marie Vien, the teacher of Adélaïde’s husband François, in the company of several friends, pupils and members of the Vien family. Marie-Gabrielle has pictured herself on the left of the canvas, looking directly at the viewer, and holding in her hand Adélaïde’s palette, on which she has just prepared the colours. The scene is like a genealogy of Marie-Gabrielle’s artistic family, with Vien as her artistic “grandfather”, in that he was a teacher of François, who in turn taught Adélaïde, who in turn taught Marie-Gabrielle [12].

The Revolution and beyond

The anti-monarchist French Revolution, which broke out in 1789, posed problems for artists such as Adélaïde and Marie-Gabrielle, who had previously enjoyed significant royal patronage. However, unlike Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, who fled from France, they both stayed, but realigned themselves somewhat as painters of Revolutionary figures. They also benefited from the increase in the number of art salons during the 1790s, and from the post-Revolutionary decision by the Louvre’s Salon Carré to welcome all artists in 1791, whether members of the Academy or not. Marie-Gabrielle was among the 21 women represented there in that year (there were 236 males), and continued to submit works in subsequent years [13].

Marie-Gabrielle gave up her artistic work in 1803 to care for Adélaïde in her final illness. After Adélaïde died, Marie-Gabrielle expanded her own range, which had for some time been dominated by miniatures, to include history painting, with a mythological representation of Hygeia, Goddess of Health. She continued to contribute works till 1814, building up a distinguished body of work ~ with a lifetime output of some 30 oils, 35 pastels and 85 miniatures, and patrons typically drawn from the ranks of the educated bourgeoisie, writers, politician and actors. She died in Paris, aged 57, in 1818.

Conclusion

Despite her obvious talent, Marie-Gabrielle fell into obscurity after she died. There were a number of reasons -- the fashion for pastels had declined, and most of her works were in private collections which became dispersed over time. The general tendency to diminish or forget the achievements of female artists would also have been a factor.

But this is not necessarily a hard-luck story. Despite her unpromising origins, Marie-Gabrielle had, in addition to her undoubted talent, the great fortune of having the encouragement, support and affection of Adélaïde and François, and enjoying a comfortable, respected and fulfilling artistic life. And we can guess that she would have been surprised and delighted if she could have known that her works would still be admired some 200 years after her death, belated as that recognition might be.

© Philip McCouat 2018, 2022. First published March 2018.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Forgotten Women Artists: Marie-Gabrielle Capet: Stepping Out from the Shadows”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. For other articles in this series, see:

Forgotten Women Artists #2: Jane Loudon: Artist, Futurist, Horticulturist and Author

Forgotten Women Artists #1: Arcangela Paladini: The Rapid Rise and Fall of a Prodigy

Forgotten Women Artists #4: Michaelina Wautier: entering the limelight after 300 years

Forgotten Women Artists #5: Thérèse Schwartze and the business of painting

Return to HOME

But this is not necessarily a hard-luck story. Despite her unpromising origins, Marie-Gabrielle had, in addition to her undoubted talent, the great fortune of having the encouragement, support and affection of Adélaïde and François, and enjoying a comfortable, respected and fulfilling artistic life. And we can guess that she would have been surprised and delighted if she could have known that her works would still be admired some 200 years after her death, belated as that recognition might be.

© Philip McCouat 2018, 2022. First published March 2018.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Forgotten Women Artists: Marie-Gabrielle Capet: Stepping Out from the Shadows”, Journal of Art in Society www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article. For other articles in this series, see:

Forgotten Women Artists #2: Jane Loudon: Artist, Futurist, Horticulturist and Author

Forgotten Women Artists #1: Arcangela Paladini: The Rapid Rise and Fall of a Prodigy

Forgotten Women Artists #4: Michaelina Wautier: entering the limelight after 300 years

Forgotten Women Artists #5: Thérèse Schwartze and the business of painting

Return to HOME

end notes

[1] See article at http://www.thearttribune.com/The-Houdon-Portrait-by-Marie.html

[2] See Exhibition Catalogue for “Marie-Gabrielle Capet: A Virtuoso of the Miniature”, Musee de Caen, Snoeck Heule, 2014 (in French)

[3] Neil Jeffares, “Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800” online edn, entry on Marie-Gabrielle Capet

[4] Vivian P Cameron, entry on Marie-Gabrielle Capet, in Delia Gaze (ed), Dictionary of Women Artists, Vol 1, page 345: see also http://siefar.org/dictionnaire/en/Marie-Gabrielle_Capet. The attribution of this work as a self-portrait by Capet has recently been doubted: see Séverine Sofio, “Gabrielle Capet’s Collective Self-Portrait: Women and Artistic Legacy in Post-Revolutionary France”, Journal 18, Issue 8, Fall 2019, footnote 9

[5] Laura Auricchio, “Self -promotion in Adélaïde Labile-Guiard’s 1785 Self-portrait with Two Students” http://www.redorbit.com/news/health/893350/selfpromotion_in_adlade_labilleguiards_1785_selfportrait_with_two_students/

[6] Auricchio, op cit

[7] Admission was in theory open to women but the proportion of female members was typically tiny, averaging about 3%

[8] Auricchio, op cit; Charlotte Foucher Zarmanian, Review of “Marie-Gabrielle Capet (1761-1818), A Virtuoso of the Miniature”, Exh Cat, Snoeck Heule, 2014

[9] Auricchio, op cit; Heather Belnap Jensen, “Picturing Paternity: the artist and father-daughter portraiture in post-revolutionary France”, in Temma Balducci & Ors (eds), Interior Portraiture and Masculine Identity in France 1789-1914

[10] Jensen, op cit; Auricchio, op cit

[11] Jensen, op cit

[12] Cameron, op cit; Jensen, op cit

[13] Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin, Women Artists 1550-1950. Los Angeles Museum of Art, Alfred Knopf, New York 1976.

© Philip McCouat 2018, 2022. First published March 2018

Return to HOME

[2] See Exhibition Catalogue for “Marie-Gabrielle Capet: A Virtuoso of the Miniature”, Musee de Caen, Snoeck Heule, 2014 (in French)

[3] Neil Jeffares, “Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800” online edn, entry on Marie-Gabrielle Capet

[4] Vivian P Cameron, entry on Marie-Gabrielle Capet, in Delia Gaze (ed), Dictionary of Women Artists, Vol 1, page 345: see also http://siefar.org/dictionnaire/en/Marie-Gabrielle_Capet. The attribution of this work as a self-portrait by Capet has recently been doubted: see Séverine Sofio, “Gabrielle Capet’s Collective Self-Portrait: Women and Artistic Legacy in Post-Revolutionary France”, Journal 18, Issue 8, Fall 2019, footnote 9

[5] Laura Auricchio, “Self -promotion in Adélaïde Labile-Guiard’s 1785 Self-portrait with Two Students” http://www.redorbit.com/news/health/893350/selfpromotion_in_adlade_labilleguiards_1785_selfportrait_with_two_students/

[6] Auricchio, op cit

[7] Admission was in theory open to women but the proportion of female members was typically tiny, averaging about 3%

[8] Auricchio, op cit; Charlotte Foucher Zarmanian, Review of “Marie-Gabrielle Capet (1761-1818), A Virtuoso of the Miniature”, Exh Cat, Snoeck Heule, 2014

[9] Auricchio, op cit; Heather Belnap Jensen, “Picturing Paternity: the artist and father-daughter portraiture in post-revolutionary France”, in Temma Balducci & Ors (eds), Interior Portraiture and Masculine Identity in France 1789-1914

[10] Jensen, op cit; Auricchio, op cit

[11] Jensen, op cit

[12] Cameron, op cit; Jensen, op cit

[13] Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin, Women Artists 1550-1950. Los Angeles Museum of Art, Alfred Knopf, New York 1976.

© Philip McCouat 2018, 2022. First published March 2018

Return to HOME