Reviews of art films

Short reviews of films about art or other topics dealt with in the Journal

An insight into the tumultuous life of Caravaggio

The 17th century painter Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio (played here by Riccardo Scamarcio), was charismatic, violent, exceptionally talented and passionate about his art, sexually-driven and attractive to both men and women. His works, largely featuring Biblical episodes, proved outwardly attractive, but at the same time they outraged many in the Church because of his practice of making his biblical characters more “real”, basing them on prostitutes and outcasts.

This film opens at a time when Caravaggio’s wild life has culminated with his being charged with a brawling murder. He flees Rome and escapes to Naples, where he enjoys the protection of the Marquise Costanza Colonna (Isabelle Huppert), but his ultimate fate depends on his getting a pardon from the Church. To that end, the Pope orders an investigator (Louis Garrel, the fictional “shadow” of the title) to examine Caravaggio’s life and works, to determine if he was worthy. It is this investigation, and its fateful consequences, which form the main focus of the film.

The film is sumptuously staged, with many of the characteristic light and shade effects which dominated Caravaggio's paintings. It offers viewers an immersive, bracing plunge into Caravaggio’s tumultuous life and times. There will be some who shrink from its excesses, but any fan of Caravaggio’s art will enjoy the experience (Caravaggio's Shadow, 2002, director Michele Placido).

The Art of the Steal

The Duke is a traditional underdog film, in which the little guy takes on the forces of authority. It tells a largely true story from the 1960s about a pensioner who achieves a cheeky notoriety after admitting to the theft of Goya’s Duke of Wellington from the National Gallery. His claimed reason for the theft is so he can claim a ransom which could be used to pay for the TV licences for elderly pensioners. Complications naturally ensue, though in this type of film we are never in doubt that everything will eventually turn out OK.

Veteran Jim Broadbent performs the main role well as a jovial well-meaning bumbler, while Helen Mirren surprisingly plays his long-suffering wife. Predictably enough, the police and court scenes are played largely for laughs. Overall, the film is entertaining enough, and the basic story is full of interest. Good viewing for a rainy afternoon: The Duke (2022), director Roger Michell

Never look away

It’s not often that you watch a three-hour film and come away wanting more. But this was the case for me with writer/director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s latest film Never Look Away (2019). The film covers three decades in the development of an artist – loosely based on the innovative Gerhard Richter -- and is set against the background of the tumultuous political events that took place in Germany, from the coming of the Nazi regime in the 1930s (including, importantly, the eugenics program), right through to the rise of contemporary art in the 1960s.

The film’s title reflects the necessity for artists to observe the world with all its faults, no matter how horrific or shocking, and the corresponding obligation of citizens not to close their eyes to the evils perpetrated by governments in their name. Veering between a romantic drama and an historical epic, the film also involves the viewer in the often-tortuous process of artistic creation (proving, incidentally, that even watching paint dry can be interesting). This film will not be to everyone’s taste, but perhaps that is part of its strength. Starring Sebastian Koch and Paula Beer, with fine cinematography by Caleb Deschanel and score by Max Richter. Rated R for graphic nudity, sexuality and brief violent images.

Hitler vs Picasso

This is an interesting full-length documentary about the artistic obsessions of Hitler’s Nazi regime.

Hitler’s belief in the power and importance of art took two forms. The first was his Nazi party’s relentless campaign against artists and artworks which were considered “degenerate” (mainly anything to do with the modern art movements of the 20th century), and their championing of art which they considered to be suitably “Aryan” (mainly sugary or heroic, reflecting the “healthy folk feeling of Germany”). The second was the Nazis’ organised looting, on a huge scale, of art treasures from the countries which they controlled or had conquered, and the extraordinary personal greed of rival collectors Hitler and his deputy Hermann Goering. Both issues are covered, with particular emphasis being placed on the personal stories of particular art dealers and those whose families who were forced to give up artworks to the authorities, or abandon them when they had to flee from racial or political persecution.

The film is introduced and narrated by Italian actor Toni Servillo (unfortunately dubbed), and draws on a number of exhibitions that have been recently mounted in the wake of the stunning 2012 discovery of the Gurlitt trove of artworks. Worthwhile viewing for insights into this extraordinary episode in the history of art. Hitler vs Picasso (and the others), Dir Claudio Poli (2018). For our detailed article on this topic, see here.

A surprising and provocative Square

You are never quite sure what’s coming next in Swedish writer/director Ruben Ostlund's ambitious and provocative The Square. Claes Bang plays Christian, a handsome, outwardly cool curator for a contemporary art museum. It is the eve of its latest major show, based on an art installation called The Square, billed as “a sanctuary for trust and caring”. But things quickly start unravelling. A one-night stand gets out of Christian’s control (with Elisabeth Moss playing a scary/funny role as victim/seducer). The theft of Christian’s phone and wallet leads to his involvement in a wildly insensitive attempt at revenge. And the publicity campaign for the exhibit goes disastrously viral for all the wrong reasons. Along the way we also encounter an unexplained gorilla, a picky beggar, a pretentious art exhibit that gets accidentally vacuumed up, and a bizarrely violent performance by an artist/ape-man. You get the idea? The scenes vary from satiric to heartfelt, with most posing questions on the appropriate limits of tolerance and levels of engagement in other people’s lives. Although the film is almost two and a half hours, it rarely drags, and constantly surprises and entertains. Be aware though it is a film that will probably produce sharply split audience reactions. The film won the Palmes d’Or at Cannes in 2017 and was nominated as best foreign language film in the 2018 Oscars. The Square (2017)

Loving Vincent

Loving Vincent is a full-length animated feature film, based on an imagined investigation into the shocking death of Vincent van Gogh from a gunshot wound to the stomach. It is based largely on interviews with the people who knew Vincent at the time, and the astonishing aspect is that all of its 60,000+ frames are hand-painted in oils. The production of the film took years, with over a hundred artists working in Vincent’s characteristic style, and adapting many of his works.

This is a film that you simply have to see, not read about. Personally, I found it visually spectacular, fascinating, even thrilling in parts, and am sure it would be rewarding for anyone who appreciates Vincent’s work, and admires courage and imagination in film-making. Loving Vincent (Dir: Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman, 2017).

An insight into the tumultuous life of Caravaggio

The 17th century painter Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio (played here by Riccardo Scamarcio), was charismatic, violent, exceptionally talented and passionate about his art, sexually-driven and attractive to both men and women. His works, largely featuring Biblical episodes, proved outwardly attractive, but at the same time they outraged many in the Church because of his practice of making his biblical characters more “real”, basing them on prostitutes and outcasts.

This film opens at a time when Caravaggio’s wild life has culminated with his being charged with a brawling murder. He flees Rome and escapes to Naples, where he enjoys the protection of the Marquise Costanza Colonna (Isabelle Huppert), but his ultimate fate depends on his getting a pardon from the Church. To that end, the Pope orders an investigator (Louis Garrel, the fictional “shadow” of the title) to examine Caravaggio’s life and works, to determine if he was worthy. It is this investigation, and its fateful consequences, which form the main focus of the film.

The film is sumptuously staged, with many of the characteristic light and shade effects which dominated Caravaggio's paintings. It offers viewers an immersive, bracing plunge into Caravaggio’s tumultuous life and times. There will be some who shrink from its excesses, but any fan of Caravaggio’s art will enjoy the experience (Caravaggio's Shadow, 2002, director Michele Placido).

The Art of the Steal

The Duke is a traditional underdog film, in which the little guy takes on the forces of authority. It tells a largely true story from the 1960s about a pensioner who achieves a cheeky notoriety after admitting to the theft of Goya’s Duke of Wellington from the National Gallery. His claimed reason for the theft is so he can claim a ransom which could be used to pay for the TV licences for elderly pensioners. Complications naturally ensue, though in this type of film we are never in doubt that everything will eventually turn out OK.

Veteran Jim Broadbent performs the main role well as a jovial well-meaning bumbler, while Helen Mirren surprisingly plays his long-suffering wife. Predictably enough, the police and court scenes are played largely for laughs. Overall, the film is entertaining enough, and the basic story is full of interest. Good viewing for a rainy afternoon: The Duke (2022), director Roger Michell

Never look away

It’s not often that you watch a three-hour film and come away wanting more. But this was the case for me with writer/director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s latest film Never Look Away (2019). The film covers three decades in the development of an artist – loosely based on the innovative Gerhard Richter -- and is set against the background of the tumultuous political events that took place in Germany, from the coming of the Nazi regime in the 1930s (including, importantly, the eugenics program), right through to the rise of contemporary art in the 1960s.

The film’s title reflects the necessity for artists to observe the world with all its faults, no matter how horrific or shocking, and the corresponding obligation of citizens not to close their eyes to the evils perpetrated by governments in their name. Veering between a romantic drama and an historical epic, the film also involves the viewer in the often-tortuous process of artistic creation (proving, incidentally, that even watching paint dry can be interesting). This film will not be to everyone’s taste, but perhaps that is part of its strength. Starring Sebastian Koch and Paula Beer, with fine cinematography by Caleb Deschanel and score by Max Richter. Rated R for graphic nudity, sexuality and brief violent images.

Hitler vs Picasso

This is an interesting full-length documentary about the artistic obsessions of Hitler’s Nazi regime.

Hitler’s belief in the power and importance of art took two forms. The first was his Nazi party’s relentless campaign against artists and artworks which were considered “degenerate” (mainly anything to do with the modern art movements of the 20th century), and their championing of art which they considered to be suitably “Aryan” (mainly sugary or heroic, reflecting the “healthy folk feeling of Germany”). The second was the Nazis’ organised looting, on a huge scale, of art treasures from the countries which they controlled or had conquered, and the extraordinary personal greed of rival collectors Hitler and his deputy Hermann Goering. Both issues are covered, with particular emphasis being placed on the personal stories of particular art dealers and those whose families who were forced to give up artworks to the authorities, or abandon them when they had to flee from racial or political persecution.

The film is introduced and narrated by Italian actor Toni Servillo (unfortunately dubbed), and draws on a number of exhibitions that have been recently mounted in the wake of the stunning 2012 discovery of the Gurlitt trove of artworks. Worthwhile viewing for insights into this extraordinary episode in the history of art. Hitler vs Picasso (and the others), Dir Claudio Poli (2018). For our detailed article on this topic, see here.

A surprising and provocative Square

You are never quite sure what’s coming next in Swedish writer/director Ruben Ostlund's ambitious and provocative The Square. Claes Bang plays Christian, a handsome, outwardly cool curator for a contemporary art museum. It is the eve of its latest major show, based on an art installation called The Square, billed as “a sanctuary for trust and caring”. But things quickly start unravelling. A one-night stand gets out of Christian’s control (with Elisabeth Moss playing a scary/funny role as victim/seducer). The theft of Christian’s phone and wallet leads to his involvement in a wildly insensitive attempt at revenge. And the publicity campaign for the exhibit goes disastrously viral for all the wrong reasons. Along the way we also encounter an unexplained gorilla, a picky beggar, a pretentious art exhibit that gets accidentally vacuumed up, and a bizarrely violent performance by an artist/ape-man. You get the idea? The scenes vary from satiric to heartfelt, with most posing questions on the appropriate limits of tolerance and levels of engagement in other people’s lives. Although the film is almost two and a half hours, it rarely drags, and constantly surprises and entertains. Be aware though it is a film that will probably produce sharply split audience reactions. The film won the Palmes d’Or at Cannes in 2017 and was nominated as best foreign language film in the 2018 Oscars. The Square (2017)

Loving Vincent

Loving Vincent is a full-length animated feature film, based on an imagined investigation into the shocking death of Vincent van Gogh from a gunshot wound to the stomach. It is based largely on interviews with the people who knew Vincent at the time, and the astonishing aspect is that all of its 60,000+ frames are hand-painted in oils. The production of the film took years, with over a hundred artists working in Vincent’s characteristic style, and adapting many of his works.

This is a film that you simply have to see, not read about. Personally, I found it visually spectacular, fascinating, even thrilling in parts, and am sure it would be rewarding for anyone who appreciates Vincent’s work, and admires courage and imagination in film-making. Loving Vincent (Dir: Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman, 2017).

|

A portrait, finally

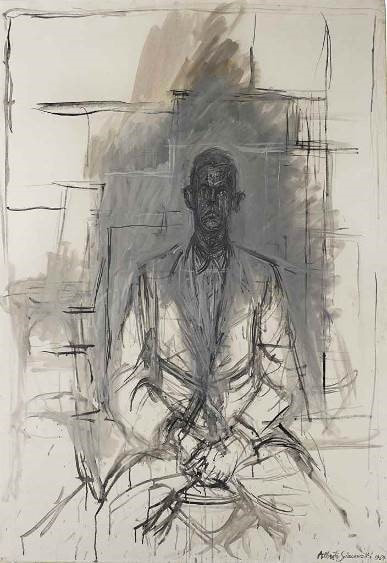

We are in the Paris of the 1960s. The celebrated Swiss/Italian sculptor and artist Alberto Giacometti, in the last years of his life, invites his friend, the well-connected young American writer James Lord, to pose for a portrait. Lord, understandably flattered, agrees. But the sittings, originally envisaged as taking only a few hours, stretch into days and even weeks. The tortured process of creating the painting that eventually emerged is now the subject of director Stanley Tucci’s new film, Final Portrait. Giacometti is memorably played by Geoffrey Rush, whose ability to portray extreme personalities is on full show. |

The artist comes across as an archetypal eccentric genius -- self-absorbed, insecure, crumpled and slovenly, wilfully stubborn, prone to tantrums, reckless with money – a man who publicly belittles his wife and flaunts his infatuation with a charismatic young prostitute, and endlessly seeks an impossible artistic perfection that perhaps only he can recognise.

Just like Giacometti's long-suffering sitter, the viewer needs patience with this film. Almost all of it is based in Giacometti’s grotty studio, giving it the static feeling of a filmed stage play. There are amusing or revealing vignettes involving Giacometti’s wife, his lover and his brother, but there is little action, a lot of repetitive behaviour and much paint drying. Overall, however, the film more than compensates with its insights into the idiosyncratic creative process and personality of a truly dedicated artist.

Final Portrait (2017) Dir Stanley Tucci. Starring Geoffrey Rush, Armie Hammer, Clémence Poésy, Tony Shalhoub, Sylvie Testud).

A homage to Bruegel in The Mill & the Cross

This unusual and memorable feature film was inspired by Pieter Bruegel’s panoramic painting, The Way to Calvary, reimagining how it was painted, and taking us inside the lives of many of the characters in it. Based on the book of the same name by Michael F Gibson, who also co-wrote the screenplay, it was directed and produced by the idiosyncratic Lech Majewski, with Rutger Hauer playing Bruegel, Michael York as Bruegel’s patron Niclaes Jongkelinck and Charlotte Rampling as the Virgin Mary.

As explained in our article on the painting, Bruegel depicts Christ’s final journey to execution but transplants it into the sixteenth century, with Flemish peasants and townspeople replacing the Jewish crowd, and the mercenary soldiers of the overlord Spanish King replacing the Romans. Director Majewski adds a further layer of fiction by presenting Bruegel as actually having witnessed this scene and painted it from life.

The film starts off as just another ordinary day – people wake up, make love, prepare for work and feed the farm animals, as children play. At the same time, preparations are being made for the execution, and fiercely cruel soldiers inflict punishments on heretics, seemingly almost at random. In addition to giving us a filmic version of the procession, the film provides an imaginary backstory for some of the characters that appear in the painting. It also enables us to listen in on Bruegel’s discussion of the painting-in-progress with his patron, and to Mary’s lament and disbelief at what is about to happen to “my son, my boy”. Considerable emphasis is placed on the role of the windmill-topped rocky crag that dominates the scene (wonderfully recreated in the film), which is taken to represent the eye of God.

As you may have gathered, this is not a typical feature film. In a sense, it alternates between different genres – part drama, part art lesson, part religious history, part documentary, part meditation, part imagination. The setting in Poland, part real, part painted and part computer generated, is impressive. And the main “plot” we already know. However, Majewski keeps the characterisation rudimentary, there is virtually no dialogue, the pacing is dreamily measured and many of the scenes of the crowd resemble re-enactments (sometimes even vast frozen tableaux), rather than convincing recreations of what occurred on the day.

For me, some of these devices work really well, but some, while brave, are not entirely convincing – perhaps I was hoping to experience more of the bustle and noise of the crowd. Overall, however, this innovative and imaginative homage to Bruegel says as much about the process of filming as it does about the process of painting, and as much about Majewski’s own artistic vision as it does about Bruegel’s – and that’s a good thing. The Mill & the Cross (2011).

The talents and obsessions of Brett Whiteley

Brett Whiteley was the most outrageously talented and versatile of Australian contemporary artists. With his youthful good looks, cocky self-confidence and glamorous wife /muse Wendy, he brought a rock star bravura to the staid Australian art scene of the 1960s. Whiteley’s paintings ranged widely from sensuous organic forms, to drug-fuelled psychological studies, serial killers, portraits, seascapes and birds, each subject being pursued with near obsessional fervour.

His life and works are the subject of this intriguing new feature-length documentary by James Bogle. The film makes use of archival footage, interviews,voice-overs, re-enactments, humorous animations -- and of course Whiteley's paintings themselves -- to provide us with an interesting and at times insightful look at a career cut short, seemingly inevitably, by the drugs that inspired and ultimately destroyed him: Whiteley (2017) Dir: James Bogle

St Peter’s and the Papal Basilicas of Rome

This film provides a unique opportunity to appreciate Rome’s magnificent Papal Basilicas without being jostled by thousands of other tourists. Shot in 3D, with interesting and informative commentary (though it's a little uncritical), it takes us on a journey round Rome, exploring the history, architecture and art treasures of St Peter’s itself, St John Lateran, St Mary Major and St Paul Outside the Walls. The film makes good use of multiple vantage points, using helicopters, drones and cameras on extendable mechanical arms. Many levels above the typical television documentary, it can be recommended for anyone interested in art history. St Peter’s and the Papal Basilicas of Rome (95 min, Sharmill Films, 2016)

Suffragette

It is an odd fact that women achieved the vote in some of Britain’s former colonies many years before they did so in Britain itself. In that country, reform was an extraordinarily protracted and at times surprisingly violent struggle. The film Suffragette covers the start of the militant stage of that campaign, initiated by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1912. This stage involved the use of calculated acts of violence – by today’s standards, minor acts of terrorism -- in an attempt to force the intransigent government’s hand (For more on the campaign, see our Suffragettes article).

The film tells its dramatic story through the exploits of a fictional working class woman (Maud Watts, well played by Carey Mulligan). Maud is a composite character who encapsulates many of the views and experiences of her class, and is present or participating at major episodes in the struggle. Her story at times borders on soap opera (in the first hour, she loses her job, her husband, her child and her home). Her willingness to give so much up for the cause is impressive, though some may consider that, as depicted here, it is somewhat of a stretch.

The film itself has some limitations. Despite its name, it ignores the efforts of a large part of the suffragette movement in Britain. The film's abrupt ending in 1913 – some 15 years before full voting rights were granted – also means that the impact of World War I is not explored. The film also does not squarely face the vexed, but fundamental, issue of whether the militancy was necessary or was actually counter-productive.

There is a great film to be made on this topic. Suffragette is not that film, because of its conscious avoidance of some big issues, and its narrative’s overdependence on Maud. However, within these self-imposed limits, it is an enjoyable, well-made and informative film that deserves a wide audience. Suffragette, 2015 (dir Sarah Gavron, written by Abi Morgan).

Just like Giacometti's long-suffering sitter, the viewer needs patience with this film. Almost all of it is based in Giacometti’s grotty studio, giving it the static feeling of a filmed stage play. There are amusing or revealing vignettes involving Giacometti’s wife, his lover and his brother, but there is little action, a lot of repetitive behaviour and much paint drying. Overall, however, the film more than compensates with its insights into the idiosyncratic creative process and personality of a truly dedicated artist.

Final Portrait (2017) Dir Stanley Tucci. Starring Geoffrey Rush, Armie Hammer, Clémence Poésy, Tony Shalhoub, Sylvie Testud).

A homage to Bruegel in The Mill & the Cross

This unusual and memorable feature film was inspired by Pieter Bruegel’s panoramic painting, The Way to Calvary, reimagining how it was painted, and taking us inside the lives of many of the characters in it. Based on the book of the same name by Michael F Gibson, who also co-wrote the screenplay, it was directed and produced by the idiosyncratic Lech Majewski, with Rutger Hauer playing Bruegel, Michael York as Bruegel’s patron Niclaes Jongkelinck and Charlotte Rampling as the Virgin Mary.

As explained in our article on the painting, Bruegel depicts Christ’s final journey to execution but transplants it into the sixteenth century, with Flemish peasants and townspeople replacing the Jewish crowd, and the mercenary soldiers of the overlord Spanish King replacing the Romans. Director Majewski adds a further layer of fiction by presenting Bruegel as actually having witnessed this scene and painted it from life.

The film starts off as just another ordinary day – people wake up, make love, prepare for work and feed the farm animals, as children play. At the same time, preparations are being made for the execution, and fiercely cruel soldiers inflict punishments on heretics, seemingly almost at random. In addition to giving us a filmic version of the procession, the film provides an imaginary backstory for some of the characters that appear in the painting. It also enables us to listen in on Bruegel’s discussion of the painting-in-progress with his patron, and to Mary’s lament and disbelief at what is about to happen to “my son, my boy”. Considerable emphasis is placed on the role of the windmill-topped rocky crag that dominates the scene (wonderfully recreated in the film), which is taken to represent the eye of God.

As you may have gathered, this is not a typical feature film. In a sense, it alternates between different genres – part drama, part art lesson, part religious history, part documentary, part meditation, part imagination. The setting in Poland, part real, part painted and part computer generated, is impressive. And the main “plot” we already know. However, Majewski keeps the characterisation rudimentary, there is virtually no dialogue, the pacing is dreamily measured and many of the scenes of the crowd resemble re-enactments (sometimes even vast frozen tableaux), rather than convincing recreations of what occurred on the day.

For me, some of these devices work really well, but some, while brave, are not entirely convincing – perhaps I was hoping to experience more of the bustle and noise of the crowd. Overall, however, this innovative and imaginative homage to Bruegel says as much about the process of filming as it does about the process of painting, and as much about Majewski’s own artistic vision as it does about Bruegel’s – and that’s a good thing. The Mill & the Cross (2011).

The talents and obsessions of Brett Whiteley

Brett Whiteley was the most outrageously talented and versatile of Australian contemporary artists. With his youthful good looks, cocky self-confidence and glamorous wife /muse Wendy, he brought a rock star bravura to the staid Australian art scene of the 1960s. Whiteley’s paintings ranged widely from sensuous organic forms, to drug-fuelled psychological studies, serial killers, portraits, seascapes and birds, each subject being pursued with near obsessional fervour.

His life and works are the subject of this intriguing new feature-length documentary by James Bogle. The film makes use of archival footage, interviews,voice-overs, re-enactments, humorous animations -- and of course Whiteley's paintings themselves -- to provide us with an interesting and at times insightful look at a career cut short, seemingly inevitably, by the drugs that inspired and ultimately destroyed him: Whiteley (2017) Dir: James Bogle

St Peter’s and the Papal Basilicas of Rome

This film provides a unique opportunity to appreciate Rome’s magnificent Papal Basilicas without being jostled by thousands of other tourists. Shot in 3D, with interesting and informative commentary (though it's a little uncritical), it takes us on a journey round Rome, exploring the history, architecture and art treasures of St Peter’s itself, St John Lateran, St Mary Major and St Paul Outside the Walls. The film makes good use of multiple vantage points, using helicopters, drones and cameras on extendable mechanical arms. Many levels above the typical television documentary, it can be recommended for anyone interested in art history. St Peter’s and the Papal Basilicas of Rome (95 min, Sharmill Films, 2016)

Suffragette

It is an odd fact that women achieved the vote in some of Britain’s former colonies many years before they did so in Britain itself. In that country, reform was an extraordinarily protracted and at times surprisingly violent struggle. The film Suffragette covers the start of the militant stage of that campaign, initiated by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1912. This stage involved the use of calculated acts of violence – by today’s standards, minor acts of terrorism -- in an attempt to force the intransigent government’s hand (For more on the campaign, see our Suffragettes article).

The film tells its dramatic story through the exploits of a fictional working class woman (Maud Watts, well played by Carey Mulligan). Maud is a composite character who encapsulates many of the views and experiences of her class, and is present or participating at major episodes in the struggle. Her story at times borders on soap opera (in the first hour, she loses her job, her husband, her child and her home). Her willingness to give so much up for the cause is impressive, though some may consider that, as depicted here, it is somewhat of a stretch.

The film itself has some limitations. Despite its name, it ignores the efforts of a large part of the suffragette movement in Britain. The film's abrupt ending in 1913 – some 15 years before full voting rights were granted – also means that the impact of World War I is not explored. The film also does not squarely face the vexed, but fundamental, issue of whether the militancy was necessary or was actually counter-productive.

There is a great film to be made on this topic. Suffragette is not that film, because of its conscious avoidance of some big issues, and its narrative’s overdependence on Maud. However, within these self-imposed limits, it is an enjoyable, well-made and informative film that deserves a wide audience. Suffragette, 2015 (dir Sarah Gavron, written by Abi Morgan).

|

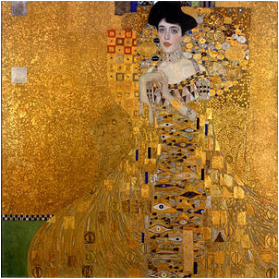

Woman in gold

Another film on the restitution of Nazi-looted art, Woman in Gold tells the real-life story of Maria Altmann, an elderly Jewish woman, and her ultimately-successful fight with the Belvedere Museum in Vienna over the ownership of Gustav Klimt’s extraordinary Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (right). Maria’s fight to recover this portrait of her aunt is resisted at every turn by the Museum, which regards the highly-valued painting as a part of the city’s heritage. |

Maria, on the other hand, who had been forced to flee from wartime Vienna, has terrible memories of the city, and of some of its citizens who eagerly joined in the Nazi-led Jewish persecutions. The film has attracted generally only lukewarm reviews, but I found it interesting and enjoyable, despite some occasional lapses. Maria is ably played by Helen Mirren, and her rather unconvincing young lawyer-friend by Ryan Reynolds. Woman in Gold, Dir Simon Curtis (2015). PS: Oddly, for a painting that meant so much to Maria, she promptly on-sold it to a New York gallery for $135 million!

Turner as a grunting genius

This impressive biopic deals with the latter years of the celebrated 19th century British painter JMW Turner, at a time of his life when he was the subject of both great acclaim and outright derision. Turner is portrayed here as severely emotionally damaged -- capable of affection but also of extreme emotional cruelty. Obsessed by the power of natural light, he is able to express himself only through his paintings, which typically featured a bold, innovative almost abstract interplay of light and weather.

The film is notable for the scenes of great natural beauty which Turner sought out to inspire his art, and deserves high praise as a serious and often beautiful attempt to portray an artist with all his strengths and faults. It is also interesting in its depiction of a society on the cusp of technological change. However it is overlong, lacks narrative drive and is at times rather stagey, seemingly lacking the artistic energy of its protagonist. Timothy Spall, obsessively grunting, grouchy and eccentric, is unforgettable in the title role: Mr Turner, Dir Mike Leigh (2014)

Matisse's late flowering success

In the last few years of his life, Henri Matisse turned to an innovative way of creating art – using scissors to create brilliantly multi-coloured paper “cut-outs” that were assembled into striking works of art. This extraordinarily productive phase in Matisse’s career, with its genesis in his earlier Dance II mural, is the subject of a new documentary film titled Exhibition: Matisse. Based on the Tate Modern’s recent blockbuster exhibition Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs (its most popular exhibition ever, with over half a million visitors), the film gives us a close-up tour of over 100 artworks, ranging from the detailed works of the Jazz collection to monumental works such as The Snail and even the stained glass windows Matisse designed for the Chapel at Vence. Although some of the curators rather waffle on, the production is livened by a striking dance interpretation and, of course, the works never fail to astonish in their freshness and impact. For lovers of Matisse’s work, this is a complete treat. Exhibition: Matisse (Dir: Phil Grabsky) 2014.

“Still Life” and the power of photographs

In the film Still Life, John May (Eddie Marsan) is a dedicated council clerk whose job it is to organise the orderly despatch of the people in the local area who have died alone. John carries out his literally thankless task with impressive respect for the dignity of his “clients” and reverence for their memories. But his attempts to find any relatives or friends to attend the funerals, while thorough, are usually fruitless. He is often the only person attending the service and the only person to hear the eulogy, written by himself from photographs and memorabilia left behind by the deceased. An unexpected change in circumstances, and a fateful meeting, eventually prompt John to revaluate his own modest, restricted and lonely life, which he has come to realise could end up in the same way as his clients, and he embarks on one last fateful case.

The film is understated, poignant and touching, and the occasional flashes of humour together with some nuanced acting by Marsan keep interest levels high. Despite its subject matter, the film is curiously life-affirming. What particularly interested me was the way in which the title itself resonated throughout the film – being reflected in John’s own quiet and restricted life, in the manner in which his efforts enable the memories of his (very) still clients to live on, and even in the cinematography of the film itself, with its series of quiet, almost static scenes. Crucially too, it is reflected in the emphasis placed on the “still life” photographs that John collects of his clients in their earlier happier days, and reverently keeps in an album which he often reflects upon. These visual frozen images play a crucial role in delivering the considerable emotional punch of the film’s final scenes and a denouement which I, for one, was not expecting. Still Life (2013) Eddie Marsan, Joanne Froggart; Dir: Uberto Pasolini.

A Vermeer?... or just a veneer?

Johannes Vermeer is regarded today as a 17th century painting genius, famous for his light effects, his precision and his ability to realistically capture the frozen moment – all attributes that we now closely associate with photography and the cinema. In recent years, the “secret” of Vermeer's ability has become the subject of intense study, and has led to controversial claims, by people such as David Hockney, that Vermeer used optical devices to assist him in his work. Now, a wealthy software and special effects inventor, Tim Jenison, has entered the dispute with a documentary film intended to provide practical evidence that even a non-painter such as himself can use optical devices to make a convincing copy of a Vermeer painting – in this case The Music Lesson. Rather oddly, the film is produced by the accomplished magicians, Penn and Teller, with Penn doubling as narrator and Teller as director. Others sympathetic to the cause, such as Hockney, also appear, though the views of doubters or dissenters are not presented.

Jenison does not simply set out to directly copy Vermeer's work. Instead, with apparently endless amounts of money, time and inventiveness, he builds from scratch the whole scene that Vermeer depicted – the room itself, the furniture, the fabrics and the people. He then paints it using a self-invented, simple-looking but ingenious combination of lenses and mirrors. The whole project literally takes years, with the actual task of painting taking an exhausting four months of obsessional persistence and patience – not to mention a very steady hand. But all the the work pays off. From what the viewer is permitted to see of the finished product, Jenison's painting appears to be of surprisingly good quality.

The film is workmanlike, interesting – at times fascinating – and well worth a look, although it does have the feeling of a stretched television special. But in the end it is a little unsatisfying. For all the money spent, the ingenuity and the years of effort, all Jenison has really done is to show that someone can reproduce the appearance of a Vermeer with the aid of optical devices. He of course has not established that Vermeer himself actually used that technique (though who knows?). And there is an even more obvious and sobering point, one which Jenison himself concedes at the end of the film. It is one thing to painstakingly copy someone else's work, but it is quite another to have the ability and inspiration to have created that work in the first place. Tim's Vermeer, Sony Pictures (2013).

A perfectly-composed film about secrets

Set in 1960s communist Poland, Ida is a remarkable film which features two sharply contrasting women who face life-changing decisions about their future. The first is Anna, a naïve young novice about to take her vows as a nun, who is confronted by some gradually-evolving but shocking discoveries about the fate of her long-lost parents and her own past identity. The other is Wanda, the novice’s aunt, a promiscuous judge whose professional and personal life is in a rapid alcoholic decline, and who has her own vital interests at stake in helping Anna discover the truth about the past.

So what is this film’s connection with art? Simply, it provides a great example of the importance of composition. Shot in a luminous black and white, many scenes involve a Vermeer-like light coming from the side, highlighting carefully-placed figures at one side or in the lower third of the screen. The slightly boxy width-to height screen ratio (the so-called Academy ratio of 1.37:1) means that the viewer does not have the wide angle of vision to which we have become accustomed. This format, an industry standard before the wide-screen formats of the 1950s, contributes to an atmosphere of claustrophobia, so appropriate for a film in which many of the characters seem trapped, either by outside forces – the strictures of life in a convent, or in the Poland of the time – or by the internal forces of their own personal limitations. At the same time, the format provides a perfect portrait-like setting for detailed close-ups of the human face, another key feature of the film. Ida (2014), director Pawel Pawlikowski; cinematography Lukasz Zal and Ryszard Lenczewski; starring Agata Trzebuchowska and Agata Kulesza.

Monuments Men misses the mark

The Monuments Men, released early in 2014, tells the unlikely but real-life story of the special multinational group of art experts that were assigned to rescue artworks stolen or confiscated by the Nazis as they retreated across Europe in the last months of World War II. The film is based very loosely on Robert Edsell’s non-fiction book of the same name.

I was particularly looking forward to seeing this film, having recently looked briefly at the Monuments Men’s intriguing activities in our article on the Isenheim Altarpiece. But maybe my expectations were set too high. Despite the promising nature of the basic story, and a cast that included George Clooney, Matt Damon and the multi-talented Cate Blanchett, I found The Monuments Men to be a considerable letdown. Clooney, who also directed and co-wrote, seems to have completely lost his touch in this project. It meanders from one half-developed plot line or character to another, alternating seemingly at random between drama and jokey comedy, and sadly failing at both. It’s a long while since I’ve seen a film that hits so many false notes as it plods from one dull, corny scene to the next, accompanied by a blaringly intrusive musical score. For all its weaknesses, though, Monuments Men at least has the merit of drawing public attention to an extraordinary episode in the history of art, one whose consequences are still reverberating today. But if you’re looking for a good film on the topic, maybe you should check out John Frankenheimer’s 1964 thriller The Train instead.

Reviving Renoir on film

Set during the First World War, this film opens with the unexpected and mysterious arrival of a young woman, Andrée, at the Riviera villa of an ageing, crippled and declining Renoir. Andrée becomes his model; her beauty and rebellious spirit entrances him and revitalises his interest in painting. Meanwhile, she falls in love with Renoir’s son Jean who has returned from the Front to convalesce. They plan a life together, but first she must convince him that he must break from his father’s attitude of simply seeing what life brings (familiar to readers of our Floating Worlds article). Don’t go to this film expecting suspense or action. Go simply if you’d like to immerse yourself in the lushly beautiful setting of the French Riviera countryside and the daily life of the eccentrically-extended Renoir household, to watch Renoir in his last great burst of creative energy and to witness the first stirrings of the career that would later make Jean famous. Renoir, 2013, dir Gilles Bourdos, Samuel Goldwyn Pictures.

Deception in art and in life

In The Best Offer, Virgil Oldman (Geoffrey Rush) is an ageing, fastidious high-end art connoisseur, dealer and auctioneer. He understands art (and sharp practices), but not people – especially women. But his interest is piqued by Claire (Sylvia Hoeks), a mysterious and obsessively-reclusive collector who wishes to auction off the contents of a crumbling mansion -- particularly when he discovers the scattered parts of what might be an immensely valuable antique automaton there. With the assistance of his likeable friend Robert (Jim Sturgess), a talented mechanical whiz (and hit with the ladies), Virgil pursues a hopelessly unlikely relationship with the beautiful but much-younger Claire, while Robert makes gradual progress with the reconstruction of the automaton. Despite the warnings of his shady accomplice, Billy (an alarmingly hairy Donald Sutherland), Virgil pushes on, neglecting his work in the hope that he has at last found a real woman to match the priceless collection of female portraits that he keeps hidden in his apartment. There is quite a lot going on in this film (did I mention the number-counting idiot savant and Virgil’s germophobia?) but, aided by its standout cinematography and production design, it manages to maintain a rather stately and enjoyable unfolding of the solution to its mysteries. The Best Offer (Writer/director Giuseppe Tornatore), 2013.

© Philip McCouat 2012 - 2022

We welcome your comments and suggestions.

Return to Home

This impressive biopic deals with the latter years of the celebrated 19th century British painter JMW Turner, at a time of his life when he was the subject of both great acclaim and outright derision. Turner is portrayed here as severely emotionally damaged -- capable of affection but also of extreme emotional cruelty. Obsessed by the power of natural light, he is able to express himself only through his paintings, which typically featured a bold, innovative almost abstract interplay of light and weather.

The film is notable for the scenes of great natural beauty which Turner sought out to inspire his art, and deserves high praise as a serious and often beautiful attempt to portray an artist with all his strengths and faults. It is also interesting in its depiction of a society on the cusp of technological change. However it is overlong, lacks narrative drive and is at times rather stagey, seemingly lacking the artistic energy of its protagonist. Timothy Spall, obsessively grunting, grouchy and eccentric, is unforgettable in the title role: Mr Turner, Dir Mike Leigh (2014)

Matisse's late flowering success

In the last few years of his life, Henri Matisse turned to an innovative way of creating art – using scissors to create brilliantly multi-coloured paper “cut-outs” that were assembled into striking works of art. This extraordinarily productive phase in Matisse’s career, with its genesis in his earlier Dance II mural, is the subject of a new documentary film titled Exhibition: Matisse. Based on the Tate Modern’s recent blockbuster exhibition Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs (its most popular exhibition ever, with over half a million visitors), the film gives us a close-up tour of over 100 artworks, ranging from the detailed works of the Jazz collection to monumental works such as The Snail and even the stained glass windows Matisse designed for the Chapel at Vence. Although some of the curators rather waffle on, the production is livened by a striking dance interpretation and, of course, the works never fail to astonish in their freshness and impact. For lovers of Matisse’s work, this is a complete treat. Exhibition: Matisse (Dir: Phil Grabsky) 2014.

“Still Life” and the power of photographs

In the film Still Life, John May (Eddie Marsan) is a dedicated council clerk whose job it is to organise the orderly despatch of the people in the local area who have died alone. John carries out his literally thankless task with impressive respect for the dignity of his “clients” and reverence for their memories. But his attempts to find any relatives or friends to attend the funerals, while thorough, are usually fruitless. He is often the only person attending the service and the only person to hear the eulogy, written by himself from photographs and memorabilia left behind by the deceased. An unexpected change in circumstances, and a fateful meeting, eventually prompt John to revaluate his own modest, restricted and lonely life, which he has come to realise could end up in the same way as his clients, and he embarks on one last fateful case.

The film is understated, poignant and touching, and the occasional flashes of humour together with some nuanced acting by Marsan keep interest levels high. Despite its subject matter, the film is curiously life-affirming. What particularly interested me was the way in which the title itself resonated throughout the film – being reflected in John’s own quiet and restricted life, in the manner in which his efforts enable the memories of his (very) still clients to live on, and even in the cinematography of the film itself, with its series of quiet, almost static scenes. Crucially too, it is reflected in the emphasis placed on the “still life” photographs that John collects of his clients in their earlier happier days, and reverently keeps in an album which he often reflects upon. These visual frozen images play a crucial role in delivering the considerable emotional punch of the film’s final scenes and a denouement which I, for one, was not expecting. Still Life (2013) Eddie Marsan, Joanne Froggart; Dir: Uberto Pasolini.

A Vermeer?... or just a veneer?

Johannes Vermeer is regarded today as a 17th century painting genius, famous for his light effects, his precision and his ability to realistically capture the frozen moment – all attributes that we now closely associate with photography and the cinema. In recent years, the “secret” of Vermeer's ability has become the subject of intense study, and has led to controversial claims, by people such as David Hockney, that Vermeer used optical devices to assist him in his work. Now, a wealthy software and special effects inventor, Tim Jenison, has entered the dispute with a documentary film intended to provide practical evidence that even a non-painter such as himself can use optical devices to make a convincing copy of a Vermeer painting – in this case The Music Lesson. Rather oddly, the film is produced by the accomplished magicians, Penn and Teller, with Penn doubling as narrator and Teller as director. Others sympathetic to the cause, such as Hockney, also appear, though the views of doubters or dissenters are not presented.

Jenison does not simply set out to directly copy Vermeer's work. Instead, with apparently endless amounts of money, time and inventiveness, he builds from scratch the whole scene that Vermeer depicted – the room itself, the furniture, the fabrics and the people. He then paints it using a self-invented, simple-looking but ingenious combination of lenses and mirrors. The whole project literally takes years, with the actual task of painting taking an exhausting four months of obsessional persistence and patience – not to mention a very steady hand. But all the the work pays off. From what the viewer is permitted to see of the finished product, Jenison's painting appears to be of surprisingly good quality.

The film is workmanlike, interesting – at times fascinating – and well worth a look, although it does have the feeling of a stretched television special. But in the end it is a little unsatisfying. For all the money spent, the ingenuity and the years of effort, all Jenison has really done is to show that someone can reproduce the appearance of a Vermeer with the aid of optical devices. He of course has not established that Vermeer himself actually used that technique (though who knows?). And there is an even more obvious and sobering point, one which Jenison himself concedes at the end of the film. It is one thing to painstakingly copy someone else's work, but it is quite another to have the ability and inspiration to have created that work in the first place. Tim's Vermeer, Sony Pictures (2013).

A perfectly-composed film about secrets

Set in 1960s communist Poland, Ida is a remarkable film which features two sharply contrasting women who face life-changing decisions about their future. The first is Anna, a naïve young novice about to take her vows as a nun, who is confronted by some gradually-evolving but shocking discoveries about the fate of her long-lost parents and her own past identity. The other is Wanda, the novice’s aunt, a promiscuous judge whose professional and personal life is in a rapid alcoholic decline, and who has her own vital interests at stake in helping Anna discover the truth about the past.

So what is this film’s connection with art? Simply, it provides a great example of the importance of composition. Shot in a luminous black and white, many scenes involve a Vermeer-like light coming from the side, highlighting carefully-placed figures at one side or in the lower third of the screen. The slightly boxy width-to height screen ratio (the so-called Academy ratio of 1.37:1) means that the viewer does not have the wide angle of vision to which we have become accustomed. This format, an industry standard before the wide-screen formats of the 1950s, contributes to an atmosphere of claustrophobia, so appropriate for a film in which many of the characters seem trapped, either by outside forces – the strictures of life in a convent, or in the Poland of the time – or by the internal forces of their own personal limitations. At the same time, the format provides a perfect portrait-like setting for detailed close-ups of the human face, another key feature of the film. Ida (2014), director Pawel Pawlikowski; cinematography Lukasz Zal and Ryszard Lenczewski; starring Agata Trzebuchowska and Agata Kulesza.

Monuments Men misses the mark

The Monuments Men, released early in 2014, tells the unlikely but real-life story of the special multinational group of art experts that were assigned to rescue artworks stolen or confiscated by the Nazis as they retreated across Europe in the last months of World War II. The film is based very loosely on Robert Edsell’s non-fiction book of the same name.

I was particularly looking forward to seeing this film, having recently looked briefly at the Monuments Men’s intriguing activities in our article on the Isenheim Altarpiece. But maybe my expectations were set too high. Despite the promising nature of the basic story, and a cast that included George Clooney, Matt Damon and the multi-talented Cate Blanchett, I found The Monuments Men to be a considerable letdown. Clooney, who also directed and co-wrote, seems to have completely lost his touch in this project. It meanders from one half-developed plot line or character to another, alternating seemingly at random between drama and jokey comedy, and sadly failing at both. It’s a long while since I’ve seen a film that hits so many false notes as it plods from one dull, corny scene to the next, accompanied by a blaringly intrusive musical score. For all its weaknesses, though, Monuments Men at least has the merit of drawing public attention to an extraordinary episode in the history of art, one whose consequences are still reverberating today. But if you’re looking for a good film on the topic, maybe you should check out John Frankenheimer’s 1964 thriller The Train instead.

Reviving Renoir on film

Set during the First World War, this film opens with the unexpected and mysterious arrival of a young woman, Andrée, at the Riviera villa of an ageing, crippled and declining Renoir. Andrée becomes his model; her beauty and rebellious spirit entrances him and revitalises his interest in painting. Meanwhile, she falls in love with Renoir’s son Jean who has returned from the Front to convalesce. They plan a life together, but first she must convince him that he must break from his father’s attitude of simply seeing what life brings (familiar to readers of our Floating Worlds article). Don’t go to this film expecting suspense or action. Go simply if you’d like to immerse yourself in the lushly beautiful setting of the French Riviera countryside and the daily life of the eccentrically-extended Renoir household, to watch Renoir in his last great burst of creative energy and to witness the first stirrings of the career that would later make Jean famous. Renoir, 2013, dir Gilles Bourdos, Samuel Goldwyn Pictures.

Deception in art and in life

In The Best Offer, Virgil Oldman (Geoffrey Rush) is an ageing, fastidious high-end art connoisseur, dealer and auctioneer. He understands art (and sharp practices), but not people – especially women. But his interest is piqued by Claire (Sylvia Hoeks), a mysterious and obsessively-reclusive collector who wishes to auction off the contents of a crumbling mansion -- particularly when he discovers the scattered parts of what might be an immensely valuable antique automaton there. With the assistance of his likeable friend Robert (Jim Sturgess), a talented mechanical whiz (and hit with the ladies), Virgil pursues a hopelessly unlikely relationship with the beautiful but much-younger Claire, while Robert makes gradual progress with the reconstruction of the automaton. Despite the warnings of his shady accomplice, Billy (an alarmingly hairy Donald Sutherland), Virgil pushes on, neglecting his work in the hope that he has at last found a real woman to match the priceless collection of female portraits that he keeps hidden in his apartment. There is quite a lot going on in this film (did I mention the number-counting idiot savant and Virgil’s germophobia?) but, aided by its standout cinematography and production design, it manages to maintain a rather stately and enjoyable unfolding of the solution to its mysteries. The Best Offer (Writer/director Giuseppe Tornatore), 2013.

© Philip McCouat 2012 - 2022

We welcome your comments and suggestions.

Return to Home