Dr Jekyll, Frankenstein and Shelley’s Heart

The curiously intertwined lives and creations of the Shelleys and Robert Louis Stevenson

By Philip McCouat For reader comments on this article, see here

1 Introduction

The themes of miraculous birth, resuscitation, reanimation, empty graves and transplants have been with us for millennia. In the Western tradition, we need only to look at the original Biblical creation story, which depends on a miraculous birth (Adam created from dust), a transplant (of Adam’s rib), and its metamorphosis into another being (the woman Eve] [1]. And if we turn to the New Testament, we have another miraculous birth (Jesus from the Virgin Mary), an empty tomb (after Jesus’s crucifixion) and resuscitations from death (Lazarus and Jesus, again). Indeed, a central theme of Christianity itself is of the possibility of an everlasting spiritual life after physical death.

In modern times, we are still struggling with ethical, legal and medical issues on these themes. So, for example, controversies rage over the availability of euthanasia, artificial prolongation of life, and the booming international trade in body parts. At the same time, scientific differences continue over how physical life began on Earth. In addition, the rise of artificial intelligence and advances in robotics raise issues of exactly where the line falls between humans and artificial creations. Even modern popular literature and film appears to be extraordinarily concerned with the half-way zones between life and death, and between humans and other beings – zombies (the walking dead), vampire bat/humans (who parasitise the living), werewolves and superheroes (often metamorphosed semi-humans).

Many of these themes, of course, also permeate Mary Shelley’s ground-breaking 1818 novel Frankenstein: A Modern Prometheus [2]. But they also haunt the lives – and particularly the deaths – of the Shelley family themselves. And, strangely enough, they would also come to be echoed in the extraordinary relationship that Robert Louis Stevenson, whose Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde itself reflected a modern variant on the Frankenstein story, would eventually establish with the Shelley family descendants.

In this article, written on the eve of the centenary of Frankenstein’s publication, we’ll be examining how these intriguing issues affected both Stevenson and the Shelleys. But first we must go back to the start of the Shelley story which, for our purposes, begins in the ‘Year Without a Summer’ of 1816.

In modern times, we are still struggling with ethical, legal and medical issues on these themes. So, for example, controversies rage over the availability of euthanasia, artificial prolongation of life, and the booming international trade in body parts. At the same time, scientific differences continue over how physical life began on Earth. In addition, the rise of artificial intelligence and advances in robotics raise issues of exactly where the line falls between humans and artificial creations. Even modern popular literature and film appears to be extraordinarily concerned with the half-way zones between life and death, and between humans and other beings – zombies (the walking dead), vampire bat/humans (who parasitise the living), werewolves and superheroes (often metamorphosed semi-humans).

Many of these themes, of course, also permeate Mary Shelley’s ground-breaking 1818 novel Frankenstein: A Modern Prometheus [2]. But they also haunt the lives – and particularly the deaths – of the Shelley family themselves. And, strangely enough, they would also come to be echoed in the extraordinary relationship that Robert Louis Stevenson, whose Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde itself reflected a modern variant on the Frankenstein story, would eventually establish with the Shelley family descendants.

In this article, written on the eve of the centenary of Frankenstein’s publication, we’ll be examining how these intriguing issues affected both Stevenson and the Shelleys. But first we must go back to the start of the Shelley story which, for our purposes, begins in the ‘Year Without a Summer’ of 1816.

2 Birth of Frankenstein’s Monster

In May 1816, the 18-year-old Mary Shelley and her lover, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, left England for Geneva. They took with them their young son William, and Mary’s step-sister Claire Godwin. After a six-week journey through a wintry and bleak Europe, the party eventually settled at Lac Léman, near the grand Villa Diodati, where Lord Byron had set up house with his personal physician John Polidori (Fig 1).

The weather continued unfavourable – Mary wrote that it “proved to be a “wet, ungenial summer, and incessant rain often confined us for days in the house” [3]. They fell into the habit of gathering at Byron’s villa, talking late into the stormy nights, in an atmosphere described as “quick, clever, sceptical, teasing and flirtatious” [4].

On one of these nights, following a suggestion by Byron, they decided to set themselves the task of each writing their own ghost story. From this modest beginning, there would emerge two novels with iconic and sensational characters. One was Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819), which in many ways became the prototype for the modern conception of vampires, some 80 years before the appearance of Bram Stoker’s Dracula [5]. The other was, of course, Mary’s Frankenstein.

According to Mary’s account, she spent some time casting round for a plot, but was eventually inspired by “one of the many and long… conversations between Lord Byron and Shelley, to which I was a devout but nearly silent listener. During one of these, various philosophical doctrines were discussed, and among others the nature of the principle of life, and whether there was any probability of its ever being discovered and communicated. … Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated; galvanism had given token of such things: perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth” [6].

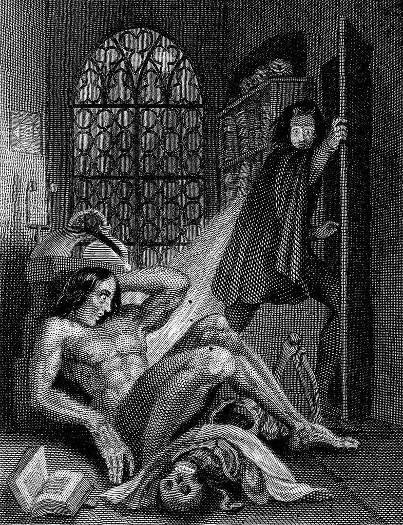

With the spur of this idea, Mary says, the outline of a plot came to her in a sort of waking dream. This eventually hardened into the story we know today – Dr Victor Frankenstein, obsessed with the idea of creating life, reconstructs an unintentionally monstrous Creature from the body parts of corpses, and re-animates it with a mysterious process. However, the Creature gets increasingly more violent and turns on its creator Frankenstein, with ultimately tragic consequences for them both [7].

On one of these nights, following a suggestion by Byron, they decided to set themselves the task of each writing their own ghost story. From this modest beginning, there would emerge two novels with iconic and sensational characters. One was Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819), which in many ways became the prototype for the modern conception of vampires, some 80 years before the appearance of Bram Stoker’s Dracula [5]. The other was, of course, Mary’s Frankenstein.

According to Mary’s account, she spent some time casting round for a plot, but was eventually inspired by “one of the many and long… conversations between Lord Byron and Shelley, to which I was a devout but nearly silent listener. During one of these, various philosophical doctrines were discussed, and among others the nature of the principle of life, and whether there was any probability of its ever being discovered and communicated. … Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated; galvanism had given token of such things: perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth” [6].

With the spur of this idea, Mary says, the outline of a plot came to her in a sort of waking dream. This eventually hardened into the story we know today – Dr Victor Frankenstein, obsessed with the idea of creating life, reconstructs an unintentionally monstrous Creature from the body parts of corpses, and re-animates it with a mysterious process. However, the Creature gets increasingly more violent and turns on its creator Frankenstein, with ultimately tragic consequences for them both [7].

The “modern Prometheus” subtitle of Frankenstein is significant ~ in one version of the Greek myth, Prometheus uses the gift of heavenly fire to quicken into life the clay figures that he uses to create the first humans.

Life, death and re-animation

Despite her extreme youth at the time, Mary was extremely well-informed of the issues of the day, and her story was intimately “connected with the favourite projects and passions of the times” [8]. Her parents were famous radicals of the day, heavily influenced by the ideals of the French Revolution. Her mother Mary Wollstonecraft, who died from complications at Mary’s birth, was the pioneer feminist author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792). Her father William Godwin was a controversial atheist, political philosopher and novelist. Mary was brought up in an emotionally cool but intensely intellectual atmosphere, with the house being visited by many of the famous writers and personalities of the day – people such as William Hazlitt, S T Coleridge, Humphrey Davy and Charles Lamb [9].

In Europe at the time, one of the issues of the day was the fundamental problem of how to define life. One school of thought, known as Vitalism, and championed by John Abernathy, was that life existed separately as a material substance, a kind of vital principle, “superadded” to the body. This vital principle was sometimes identified with the soul, conferred by God. The other school of thought, Materialism, championed by William Lawrence, was that life was simply the working operation of all the body’s functions in relationship to one another. These competing views would have been well known to the Shelleys -- Percy had read one of Abernethy’s books and quoted it in his own work, and Lawrence had been the Shelleys’ doctor [10].

Another major talking point was how, in practical terms, you could determine whether a person was actually dead. Some in the medical community believed that anything short of putrefaction could be an “ïncomplete” (as distinct from “absolute”) death. This fuelled public concern that, if it was not always possible to be sure whether a person was truly dead, there was also a possibility of being buried alive [11]. This in turn led a craze in “life preserving coffins” from which the recently-buried who “woke up” would be able to use one of a number of mechanical devices to alert passers-by that they were alive.

If someone apparently dead could just spontaneously “wake up” in this way, was it also possible that they could be artificially resuscitated or reanimated? This issue achieved much currency as a result of the efforts of Royal Humane Society. Founded in 1774, its aims were to publish information to help people resuscitate others, even paying for attempts to save lives. Regular publicity was given to those people who were “‘raised from the dead”’ by the Society’s methods. These, of course, may sometimes have included people who had deliberately intended suicide.

Such death-to-life situations would have been vividly brought home to Mary, as her own mother Mary Wollstonecraft had herself been resuscitated from drowning – after leaping from a bridge into the Thames in the depths of depression, she had complained, “‘I have only to lament, that, when the bitterness of death was past, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery” [12]. Furthermore, as we have said, her mother’s eventual “real” death came about as a result of Mary’s birth. And for good measure, Mary had experienced a vivid dream that her own first baby, who had died after only a few days, “came to life again” after it was rubbed before the fire [13].

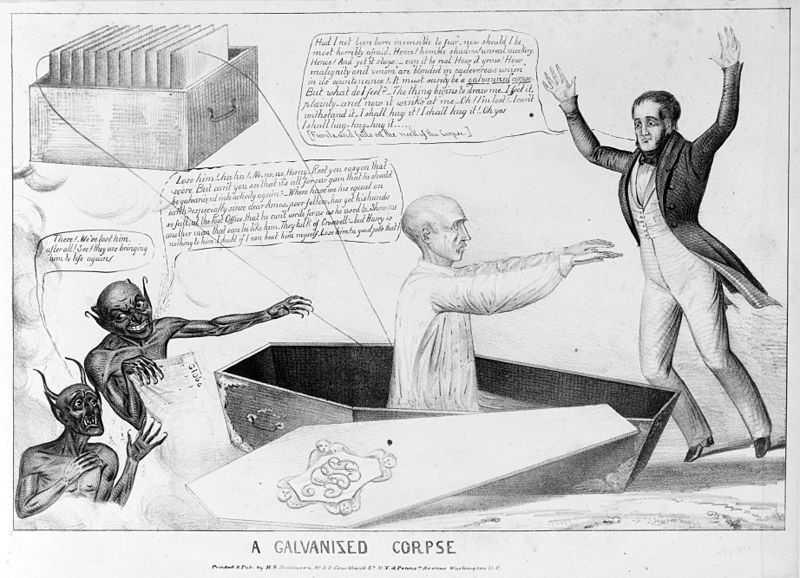

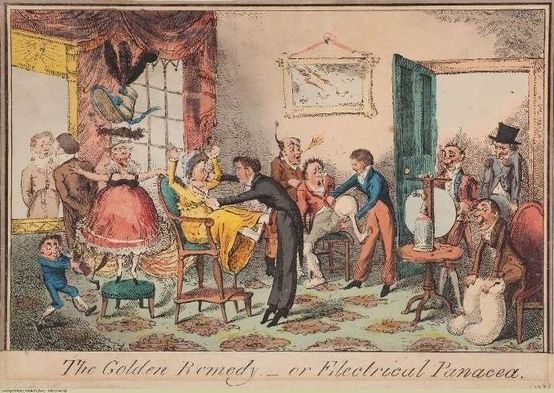

And it was not just the incompletely dead. There were serious attempts, too, to reanimate the absolutely dead. These efforts typically involved the application of electricity. In widely-publicised experiments, Luigi Galvani found that amputated frog’s legs twitched as if alive when struck by a spark of electricity. Shelley himself had experimented with electricity and “galvanism” and, as we have already seen, Mary Shelley specifically mentions it as an influence upon her story. Mary and Percy also knew, and attended a lecture by, Andrew Crosse, who had been experimenting with harnessing the explosive power of the electric charges in the air, particularly during thunderstorms.

Another major talking point was how, in practical terms, you could determine whether a person was actually dead. Some in the medical community believed that anything short of putrefaction could be an “ïncomplete” (as distinct from “absolute”) death. This fuelled public concern that, if it was not always possible to be sure whether a person was truly dead, there was also a possibility of being buried alive [11]. This in turn led a craze in “life preserving coffins” from which the recently-buried who “woke up” would be able to use one of a number of mechanical devices to alert passers-by that they were alive.

If someone apparently dead could just spontaneously “wake up” in this way, was it also possible that they could be artificially resuscitated or reanimated? This issue achieved much currency as a result of the efforts of Royal Humane Society. Founded in 1774, its aims were to publish information to help people resuscitate others, even paying for attempts to save lives. Regular publicity was given to those people who were “‘raised from the dead”’ by the Society’s methods. These, of course, may sometimes have included people who had deliberately intended suicide.

Such death-to-life situations would have been vividly brought home to Mary, as her own mother Mary Wollstonecraft had herself been resuscitated from drowning – after leaping from a bridge into the Thames in the depths of depression, she had complained, “‘I have only to lament, that, when the bitterness of death was past, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery” [12]. Furthermore, as we have said, her mother’s eventual “real” death came about as a result of Mary’s birth. And for good measure, Mary had experienced a vivid dream that her own first baby, who had died after only a few days, “came to life again” after it was rubbed before the fire [13].

And it was not just the incompletely dead. There were serious attempts, too, to reanimate the absolutely dead. These efforts typically involved the application of electricity. In widely-publicised experiments, Luigi Galvani found that amputated frog’s legs twitched as if alive when struck by a spark of electricity. Shelley himself had experimented with electricity and “galvanism” and, as we have already seen, Mary Shelley specifically mentions it as an influence upon her story. Mary and Percy also knew, and attended a lecture by, Andrew Crosse, who had been experimenting with harnessing the explosive power of the electric charges in the air, particularly during thunderstorms.

The next highly-controversial step in attempted re-animation was taken by Galvani’s nephew, Giovanni Aldini, who applied electricity to hanged criminals. This public testing on human corpses had been made possible by the Murder Act of 1752, which enabled judges to add the indignity of dissection to hanging as the punishment for particularly severe crimes. In one 1803 experiment, for example, onlookers reported that the dead man’s eye opened (as would later happen with Frankenstein’s Creature), his right hand was raised and clenched, and his legs moved. Another experiment, in 1812, on the corpse of the convicted assassin John Bellingham, resulted in his removed heart being stimulated into beating for four hours by the application of a Galvanistic electric current [14].

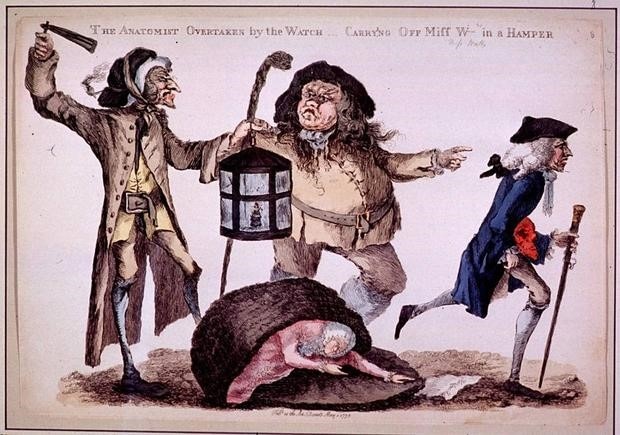

However, it was one thing to make a corpse make life-like twitches, and quite another to actually bring it back to life. The growing realisation of this, coupled with public unease and revulsion at the spectacle, eventually led to the discontinuance of these performances. This however did not end the need for fresh corpses. Advances in medical science and education required a steady stream of corpses for dissection by trainee surgeons. But there were never enough to meet the demand, and a black market grew up, with ghoulish “body snatchers” or “resurrection men” (Fig 5), who would raid graveyards, normally at night, dig up freshly-buried bodies and resell them. Some medical students actually resorted to this practice themselves. Mary and Shelley were personally acquainted with this state of affairs, as they actually courted in the churchyard at Old St Pancras in. London, where Mary’s mother had been buried. The extensive graveyard there had a reputation as a favoured place for body snatchers [15]. So bad was the problem that heavy iron enclosures known as "mortsafes" were often used in an attempt to discourage or prevent violation of new graves.

All of these issues would come together, and be even further extended, in Frankenstein. In Mary’s story, grave robbing to obtain body parts finds its echo in Dr Frankenstein spending “days and nights in vaults and charnel-houses” to “observe the natural decay and corruption of the human body” [16]. Vitalism and re-animation are realised in Frankenstein’s creation of an entirely new being, reconstructed and re-animated from dead matter by the spark of vitality. Medical dissections are transformed into an experiment which is essentially a “surgical operation, a corpse dissection, in reverse” [17]. And the ultimately tragic results of Frankenstein’s experiment became an acknowledgement of the dangers of “playing God”, and pushing science beyond its traditional borders.

3 Death of Shelley

Some four years after Frankenstein had been published and become famous, the Shelleys were in Italy, having effectively exiled themselves from England. In June 1822 they were living in the rather ramshackle Casa Magni, near Lerici, a small Italian town in the Bay of Spezia, together with their friends the Williamses. On 30 June, Shelley, Williams and a young deckhand Charles Vivian sailed to Livorno on board the 24 ft sailboat Don Juan (aka Ariel). After a few days there, they set out on the return voyage. However, within a half an hour, a squall came on, strengthening to a hard gale [18].

The Don Juan never made it home – it foundered and all three of its crew perished. After a week or so, two bodies were washed up, three miles apart, on the shore near Viareggio. They were the remains of Shelley and Williams [19]. Their prolonged immersion meant that they had seriously deteriorated, and local quarantine laws required that they be buried, with lime, in the sand. The bodies were identified by Shelley’s friends, Leigh Hunt, Lord Byron and Charles Trelawny. Shelley was not facially recognisable, and could be recognised only by his slight, lanky build and (it is said) a volume of Keats’ poetry in his pocket.

Mary, however, was determined that Shelley should instead be buried next to his son William in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome [20]. Trelawny finally obtained permission from the authorities to exhume the bodies, cremate the remains and transport the ashes from the site. By now, the remains were over a month old. Trelawny reported that all that was left of Williams was “a shapeless mass of bones and flesh” [21]. His body started falling apart into pieces during his disinterment. In Trelawny’s account, an aghast Byron described it as a “nauseous and degrading sight”, commenting, ”What is a human body? Are we all to resemble that? Why it might be the carcass of a sheep, for all I can see” [22].

Cremation, dispersal and burial

Using a makeshift iron furnace, William’s body was eventually reduced to ashes, though not without difficulty. The three then returned the next day to perform the same unpleasant task for Shelley. It took an hour’s digging to find him. Like Williams, he was shockingly disfigured; his “face and hands, and parts of the body not protected by [clothes], were fleshless”, and he was stained a “ghastly indigo colour” [23].

Byron asked Trelawny for the skull to be reserved from him but, as Trelawny later claimed, Byron “had previously used [another person’s skull] as a drinking cup, [so] I was determined Shelley’s should not be so profaned”. The furnace was then fired, using larger pieces of timber than had been used for Williams. Trelawny describes the grisly, pagan-inspired, scene:

“More wine was poured over Shelley’s dead body than he had consumed during his life. This with the oil [Frankincense] and salt made the yellow flames glisten and quiver. The heat from the sun and fire was so intense that the atmosphere was tremulous and wavy. The corpse fell open and heart was laid bare. The frontal bone of the skull, where it had been struck by the mattock, fell off; and, as the back of the head rested on the red-hot bottom bar of the furnace, the brains literally seethed, bubbled and boiled as in a cauldron, for a very long time” [24].

Byron had in the meantime prudently absented himself, having gone for a swim before the cremation began [25]. Leigh Hunt too abstained, and stayed in his coach. Finally, however, Shelley’s body was reduced to grey ashes, with some fragments of bones, the jaw and the skull. But one more bizarre act was to follow. “What surprised us all”, reported Trelawny, “was that the heart remained entire. In snatching this relic from the fire, my hand was severely burnt; and had anyone seen me do the act I should have been put into quarantine” [26]. Leigh Hunt also commented on how the “unusually large” heart remained virtually untouched even though all around it was reduced to dust.

Byron asked Trelawny for the skull to be reserved from him but, as Trelawny later claimed, Byron “had previously used [another person’s skull] as a drinking cup, [so] I was determined Shelley’s should not be so profaned”. The furnace was then fired, using larger pieces of timber than had been used for Williams. Trelawny describes the grisly, pagan-inspired, scene:

“More wine was poured over Shelley’s dead body than he had consumed during his life. This with the oil [Frankincense] and salt made the yellow flames glisten and quiver. The heat from the sun and fire was so intense that the atmosphere was tremulous and wavy. The corpse fell open and heart was laid bare. The frontal bone of the skull, where it had been struck by the mattock, fell off; and, as the back of the head rested on the red-hot bottom bar of the furnace, the brains literally seethed, bubbled and boiled as in a cauldron, for a very long time” [24].

Byron had in the meantime prudently absented himself, having gone for a swim before the cremation began [25]. Leigh Hunt too abstained, and stayed in his coach. Finally, however, Shelley’s body was reduced to grey ashes, with some fragments of bones, the jaw and the skull. But one more bizarre act was to follow. “What surprised us all”, reported Trelawny, “was that the heart remained entire. In snatching this relic from the fire, my hand was severely burnt; and had anyone seen me do the act I should have been put into quarantine” [26]. Leigh Hunt also commented on how the “unusually large” heart remained virtually untouched even though all around it was reduced to dust.

How could the heart have survived the fire? Nobody is really sure. In a 1955 article in The Journal of the History of Medicine, Arthur Norman suggested that Shelley may have suffered from "a progressively calcifying heart … which indeed would have resisted cremation as readily as a skull, a jaw or fragments of bone." [27]. On the other hand, it has been suggested that the organ that Trelawny rescued from the fire was not Shelley’s heart at all, but his liver. A letter to the New York Times in 1885 referred to an article which stated that a liver is far more resistant to destruction by fire than a heart, and that this applies even more so when the organs have been saturated with water. Somehow, cherishing a dear departed’s liver is not quite as poetic as cherishing their heart (though both have their grisly aspects), though there was of course no doubt in Mary’s mind.

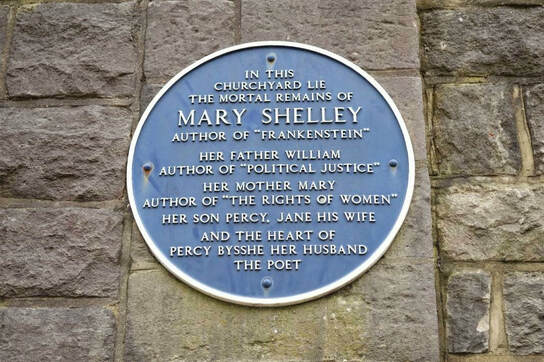

Meanwhile, Shelley’s ashes were eventually buried in Rome, as Mary wished, though the plan to bury him in the same grave as his son William was thwarted by the macabre discovery that William’s bones had disappeared, presumably dug up and disposed of by persons unknown [28]. Such disinterment seemed to be a constant theme with the Shelleys. It was, of course, an element in Frankenstein, but it is a macabre fact that Mary’s son, husband and both parents (William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft) were all dug up from their graves for one reason or another – Shelley from his initial graves in the sand, and the parents as a result of a later decision to relocate them to Bournemouth where Mary was buried [29].

On the night after the cremation, Byron suffered some agonising consequences of his midday swim – a sunburn so bad that he became “one large continuous blister”, followed by “his whole skin coming off”. Two weeks later he had (literally) recovered, with “a new skin”, making him as “glossy as a snake in its new suit” [30].

This incident with Byron was oddly evocative of the effect of the fire on Shelley’s body. Indeed, the whole episode on the beach would, apart from the natural distress for Mary, have surely carried grim echoes for her, had she attended. The repeated disinterments and the separation of body parts (particularly in the case of Williams) would have surely recalled Frankenstein’s own dealings with grave robbers and the body parts he used to create his monster. The fiery corpse could recall the mythical Promethean fire used in creating the first humans. And Byron’s despairing comment about the nature of a human body would echo the central issue of the line between humans and monsters, and between life and death.

Meanwhile, Shelley’s ashes were eventually buried in Rome, as Mary wished, though the plan to bury him in the same grave as his son William was thwarted by the macabre discovery that William’s bones had disappeared, presumably dug up and disposed of by persons unknown [28]. Such disinterment seemed to be a constant theme with the Shelleys. It was, of course, an element in Frankenstein, but it is a macabre fact that Mary’s son, husband and both parents (William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft) were all dug up from their graves for one reason or another – Shelley from his initial graves in the sand, and the parents as a result of a later decision to relocate them to Bournemouth where Mary was buried [29].

On the night after the cremation, Byron suffered some agonising consequences of his midday swim – a sunburn so bad that he became “one large continuous blister”, followed by “his whole skin coming off”. Two weeks later he had (literally) recovered, with “a new skin”, making him as “glossy as a snake in its new suit” [30].

This incident with Byron was oddly evocative of the effect of the fire on Shelley’s body. Indeed, the whole episode on the beach would, apart from the natural distress for Mary, have surely carried grim echoes for her, had she attended. The repeated disinterments and the separation of body parts (particularly in the case of Williams) would have surely recalled Frankenstein’s own dealings with grave robbers and the body parts he used to create his monster. The fiery corpse could recall the mythical Promethean fire used in creating the first humans. And Byron’s despairing comment about the nature of a human body would echo the central issue of the line between humans and monsters, and between life and death.

|

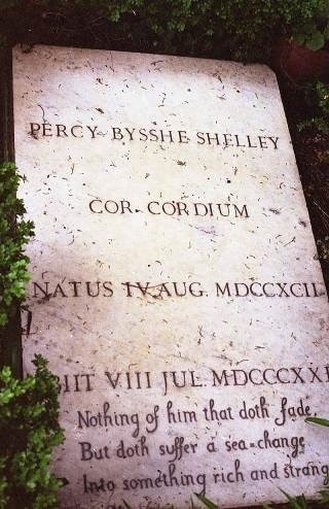

Shelley’s burial (or rather re-burial) in Rome was presided over by the ubiquitous Trelawny, who had also bought the neighbouring plot so he could be buried there himself. Trelawny also arranged for Shelley’s grave to bear the inscription, taken from Shakespeare’s The Tempest:

Cor cordium [Heart of Hearts]/Nothing of him that doth fade /But doth suffer a sea-change / Into something rich and strange. The inscription presumably refers to Shelley’s immortal reputation, though its reference to a “sea change into something rich and strange” once again echoes the theme of metamorphosis. The inscription also refers to the “heart of hearts”, but Shelley’s heart was not buried there at all. |

After Trelawny’s seizure of it from the cremation ashes, Leigh Hunt had claimed entitlement, but after an unseemly custody battle, and what Mary remembered as bitter quarrel, he was eventually convinced to hand it over to her [31].

4 Shelley’s heart and the birth of the Shelley myth

Today, Shelley is commonly seen as a leading Romantic poet. The concept of “Romantic” in this context carries a number of overlapping ideas. A Romantic is likely to favour intuition and imagination over reason, subjective over objective, pastoral over urban, ancient over modern, exotic over local; and have spontaneous overflows of powerful heart-felt but sometimes lonely and melancholy feelings.

But back in 1822, Shelley was not so highly regarded. To the Establishment, he was a political radical and a vigorously expressed atheist with a predilection for extremely young lovers [32]. And outside his own literary circles he was not so widely known to the general public. In reporting his death, the conservative press was overwhelmingly unfavourable and dismissive. The Courier, for example, said, “Shelley, the writer of some infidel poetry has been drowned; now he knows whether there is a God or no” [33].

Mary, with the overwhelming grief of a widow who felt that she has somehow failed to do justice to her spouse in life, determined to ensure that his reputation be exalted after his death [34]. In her widow’s status, she saw herself as "a human creature blessed by an elemental spirit's company & love - an angel who imprisoned in flesh could not adapt himself to his clay shrine & so has flown and left it." [35]. Mary was determined to tap into a developing public preoccupation with the figure of the creative genius – a preoccupation which stemmed in part from romantic poetry, John Keats’ recent death and Byron’s celebrity – in order to recreate Shelley as the voice of Romantic isolation [36].

Mary developed this version of Shelley in the novels she wrote in the 1830s in which she depicted characters who were charismatic, embittered and lonely, figments of tortured brilliant individualism. This culminated in the four volume Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, with lengthy biographical material which presented him as an ideal uniquely creative individual, who delivered up his soul to poetry, with an “intensity of perception which enabled him to understand the world anew and distanced him from petty concerns” [37]. It seems a far cry from the committed political radical that he actually had been (and which had placed him in such disfavour during his lifetime).

While this was going on, what had happened to Shelley’s miraculously preserved heart? It would come to have a very special place in the Shelley myth. Hermione Lee has noted that it is “one of the most complicated and charged examples in British biography of the contested use of sources, or rival versions and myth making, in which a body part comes to symbolise the subject’s afterlife” [38].

Mary kept it, supposedly wrapped in a silken shroud, and was said to carry it with her, in her writing case, for years. After she died, it was found in a desk drawer, apparently wrapped in a copy of one of Shelley’s final poems, Adonais, a 55 verse elegy on the death of John Keats. Along with all the family archives, the heart then passed to Shelley’s son Sir Percy Shelley, who had inherited a baronetcy on the death of his grandfather in 1844.

Sir Percy’s wife, Lady Shelley, took a particular interest in the heart. She had been devoted to her mother-in-law Mary and took a keen, even fanatical, interest in preserving and protecting the Shelley family’s literary heritage. Following Mary’s death she took it upon herself to virtualise canonise the Shelleys. At Boscombe Manor she created a Shelley Sanctum, a small room with a domed ceiling painted with stars, and lit by a red lamp. Here the precious Shelley relics, papers, manuscripts and letters were kept and selectively displayed [39]. Over the mantelpiece hung a painting of Mary by Rothwell (see Fig 3) [40]. There was also a death mask of Mary Wollstonecraft, and the urn in which Shelley’s heart was kept. Lady Shelley regarded this as her special room, “the spot then where I love to sit and where I spend all my time when I am alone” [41].

The circumstances of Shelley’s death also received a retrospective makeover. At the end of the sanctum stood a scale replica of the memorial Lady Shelley had commissioned from Henry Weekes, and installed in Christchurch Priory. Derived from Michelangelo's Pietá, it depicts Mary cradling the drowned Shelley in her arms (though this of course did not happen) (Fig 12). The likening of the paganistic Shelley to Jesus is bold, if not bizarre, though his association with the idea of resurrection is oddly symptomatic of one of the themes that recur this story. Lady Shelley also commissioned a statue of Shelley by Edward Onslow Ford, now displayed at University College, Oxford, depicting the body of Shelley washed ashore, miraculously unscathed by days in the water.

But back in 1822, Shelley was not so highly regarded. To the Establishment, he was a political radical and a vigorously expressed atheist with a predilection for extremely young lovers [32]. And outside his own literary circles he was not so widely known to the general public. In reporting his death, the conservative press was overwhelmingly unfavourable and dismissive. The Courier, for example, said, “Shelley, the writer of some infidel poetry has been drowned; now he knows whether there is a God or no” [33].

Mary, with the overwhelming grief of a widow who felt that she has somehow failed to do justice to her spouse in life, determined to ensure that his reputation be exalted after his death [34]. In her widow’s status, she saw herself as "a human creature blessed by an elemental spirit's company & love - an angel who imprisoned in flesh could not adapt himself to his clay shrine & so has flown and left it." [35]. Mary was determined to tap into a developing public preoccupation with the figure of the creative genius – a preoccupation which stemmed in part from romantic poetry, John Keats’ recent death and Byron’s celebrity – in order to recreate Shelley as the voice of Romantic isolation [36].

Mary developed this version of Shelley in the novels she wrote in the 1830s in which she depicted characters who were charismatic, embittered and lonely, figments of tortured brilliant individualism. This culminated in the four volume Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, with lengthy biographical material which presented him as an ideal uniquely creative individual, who delivered up his soul to poetry, with an “intensity of perception which enabled him to understand the world anew and distanced him from petty concerns” [37]. It seems a far cry from the committed political radical that he actually had been (and which had placed him in such disfavour during his lifetime).

While this was going on, what had happened to Shelley’s miraculously preserved heart? It would come to have a very special place in the Shelley myth. Hermione Lee has noted that it is “one of the most complicated and charged examples in British biography of the contested use of sources, or rival versions and myth making, in which a body part comes to symbolise the subject’s afterlife” [38].

Mary kept it, supposedly wrapped in a silken shroud, and was said to carry it with her, in her writing case, for years. After she died, it was found in a desk drawer, apparently wrapped in a copy of one of Shelley’s final poems, Adonais, a 55 verse elegy on the death of John Keats. Along with all the family archives, the heart then passed to Shelley’s son Sir Percy Shelley, who had inherited a baronetcy on the death of his grandfather in 1844.

Sir Percy’s wife, Lady Shelley, took a particular interest in the heart. She had been devoted to her mother-in-law Mary and took a keen, even fanatical, interest in preserving and protecting the Shelley family’s literary heritage. Following Mary’s death she took it upon herself to virtualise canonise the Shelleys. At Boscombe Manor she created a Shelley Sanctum, a small room with a domed ceiling painted with stars, and lit by a red lamp. Here the precious Shelley relics, papers, manuscripts and letters were kept and selectively displayed [39]. Over the mantelpiece hung a painting of Mary by Rothwell (see Fig 3) [40]. There was also a death mask of Mary Wollstonecraft, and the urn in which Shelley’s heart was kept. Lady Shelley regarded this as her special room, “the spot then where I love to sit and where I spend all my time when I am alone” [41].

The circumstances of Shelley’s death also received a retrospective makeover. At the end of the sanctum stood a scale replica of the memorial Lady Shelley had commissioned from Henry Weekes, and installed in Christchurch Priory. Derived from Michelangelo's Pietá, it depicts Mary cradling the drowned Shelley in her arms (though this of course did not happen) (Fig 12). The likening of the paganistic Shelley to Jesus is bold, if not bizarre, though his association with the idea of resurrection is oddly symptomatic of one of the themes that recur this story. Lady Shelley also commissioned a statue of Shelley by Edward Onslow Ford, now displayed at University College, Oxford, depicting the body of Shelley washed ashore, miraculously unscathed by days in the water.

The myth making continued with Fournier’s Funeral of Shelley (Fig 13). This work, while being suitably poetical and funereal in tone, is factually misleading in many ways. The artist, from his viewpoint some 67 years after Shelley’s death, has depicted a cold windswept beach at evening, with a well-rugged Trelawny, Hunt and Byron standing mournfully watching a smouldering funeral pyre, where a pale Shelley peacefully lies on his back, as if he has gently dropped off to sleep. In the background is his stricken widow Mary who is on her knees, weeping and praying.

In fact, as we have seen, the cremation took place in the broiling heat of the day; Leigh Hunt had retired to his carriage; a sickened Byron went for a swim rather than witness the cremation; and Mary Shelley was not there at all. In addition, Shelley’s body was largely fleshless and grotesquely stained after being in the water for a week and buried in lime for weeks more. The disinterment and cremation was therefore horrifying and grisly in the extreme – far from the impression of quiet, melancholy, dignified and even romantic atmosphere Fournier was trying to convey.

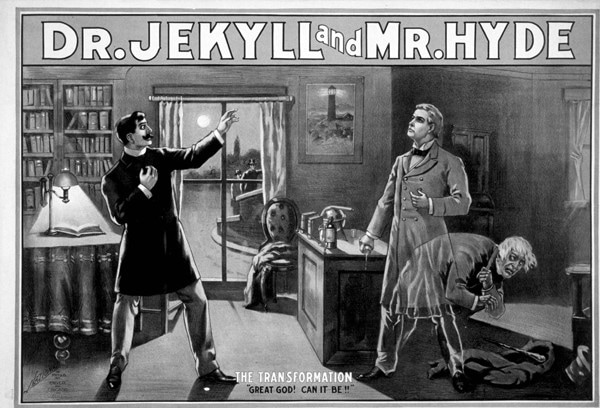

5 Dr Jekyll creates Mr Hyde

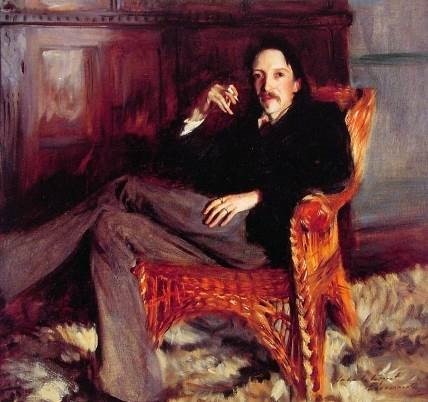

We now need to turn to the other main character in this story, the 19th century Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. RLS, as we shall call him him, was plagued with bad health. He once described himself as a “mere complication of cough and bones” [42]. He travelled widely, in Europe and the United States (where he married), and in 1885 his search led him and his wife Fanny to the sea air and (relatively) mild climate of Westbourne, a village in the Bournemouth area of England. Here they spent the summers in a house he named Skerryvore [43]. By this stage, RLS was already a popular author, particularly as a result of Treasure Island (1882), but it was at Skerryvore that he would write his sensational novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), the work that would elevate him into a major literary celebrity [44].

In this book, the outwardly respectable Dr Jekyll, realising with shame that he has an evil side to his personality, concocts a potion in his laboratory that will enable him to act out his fantasies in the guise of a new guilt-free character, Mr Edward Hyde. The potion is such that Mr Hyde is both physically and psychologically a monstrously transformed version of Jekyll. Initially, the experiment is a success, as Jekyll is now free to indulge both sides of his personality. But eventually Hyde’s actions get murderously extreme; Jekyll can no longer control him and cannot control when the transformations take place. Knowing that a final irrevocable transformation to Hyde is imminent, Jekyll takes poison.

Although this was written almost 70 years after Frankenstein, both works have a number of obvious similarities. Both stories involve obsessed doctors/scientists overstepping the mark, successfully creating a new life, losing control of their hideous inhuman creation, and eventually getting their comeuppance as creator and creature become more and more intertwined.

There are also coincidences in the circumstances of the writing of both books ~ both were written away from the author’s home country, both were partly inspired by a dream of the author’s, and both were written in the form of a series of letters. Both reflected major issues that were current at the time ~ in the case of Frankenstein the vitalism and nature-of-life debates and, in the case of Jekyll and Hyde, the psychological concept of dualism – the good and the base evil instincts that are part of human nature -- which had become a common motif in the nineteenth century [45].

Both books became massive sellers, their central characters becoming bywords in common usage ~ a “Frankenstein” creation and a “Jekyll and Hyde” personality. Both have inspired countless spin-offs on the stage, screen and literature and, I would expect, are today known more from these sources than from any actual reading of the books themselves. Indeed, as Claire Harman says of Jekyll and Hyde, “the story is now so embedded in popular culture that it hardly exists as a work of literature” [46].

There are also coincidences in the circumstances of the writing of both books ~ both were written away from the author’s home country, both were partly inspired by a dream of the author’s, and both were written in the form of a series of letters. Both reflected major issues that were current at the time ~ in the case of Frankenstein the vitalism and nature-of-life debates and, in the case of Jekyll and Hyde, the psychological concept of dualism – the good and the base evil instincts that are part of human nature -- which had become a common motif in the nineteenth century [45].

Both books became massive sellers, their central characters becoming bywords in common usage ~ a “Frankenstein” creation and a “Jekyll and Hyde” personality. Both have inspired countless spin-offs on the stage, screen and literature and, I would expect, are today known more from these sources than from any actual reading of the books themselves. Indeed, as Claire Harman says of Jekyll and Hyde, “the story is now so embedded in popular culture that it hardly exists as a work of literature” [46].

6 RLS is “adopted” by the Shelleys

The connections between Stevenson and the Shelleys are not, however, limited to these parallels in their works. For it happened that at the very time that RLS was writing Jekyll in Bournemouth, Shelley’s son Sir Percy, and Lady Shelley, also lived there, in the nearby Boscombe Manor, not far from the Stevensons [47]. This was to give rise to a curious form of association.

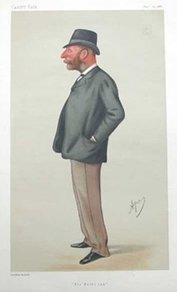

Sir Percy, quite unlike his father Shelley, led the life of an amiable country squire, supporting local societies and worthy causes, and indulging his numerous hobbies: sailing, keeping dogs, photography, bicycling and tricycling, and amateur dramatics [48]. An 1879 Vanity Fair article reported that “he delights above all in yachting and in private theatricals, and is even now engaged in building a theatre for amateur performers” [49]. The theatre was attached to the house, and was described as the most splendid private theatre in England. Sir Percy’s plays were very close to his heart, to the extent that he often wrote, performed in and produced them, as well as painting the scenery and composing the music. They commonly had a humorous edge, with titles such as He Whoops to Conquer or A Comedy of Terrors [50].

Sir Percy, quite unlike his father Shelley, led the life of an amiable country squire, supporting local societies and worthy causes, and indulging his numerous hobbies: sailing, keeping dogs, photography, bicycling and tricycling, and amateur dramatics [48]. An 1879 Vanity Fair article reported that “he delights above all in yachting and in private theatricals, and is even now engaged in building a theatre for amateur performers” [49]. The theatre was attached to the house, and was described as the most splendid private theatre in England. Sir Percy’s plays were very close to his heart, to the extent that he often wrote, performed in and produced them, as well as painting the scenery and composing the music. They commonly had a humorous edge, with titles such as He Whoops to Conquer or A Comedy of Terrors [50].

Fig 16: Caricature of Sir Percy Shelley, “The poet’s son”, Vanity Fair 1879

Fig 16: Caricature of Sir Percy Shelley, “The poet’s son”, Vanity Fair 1879

The Stevensons and the Shelleys soon become very friendly – in Fanny’s description “rather intimate”. The Stevensons would frequently visit and they were allowed to inspect the Shelley Sanctum there [51]. RLS was fascinated with the death mask portrait, which Fanny describes as “the most entrancing thing ever seen” [52]. She wrote that “Lady Shelley is delicious; naturally no longer young, suffering from the effects of a terrible accident that has left her a hopeless invalid, but with all the fire of youth, and as mad as some other people you know, and ready to plunge into any wild extravagance at a moment’s notice”.

In the same letter she noted, “Sir Percy is an odd creature! Do you know him? He is the poet’s son only in being so exceedingly curious. I think we will come to be very fond of him”[53].

In the same letter she noted, “Sir Percy is an odd creature! Do you know him? He is the poet’s son only in being so exceedingly curious. I think we will come to be very fond of him”[53].

Sir Percy photographed RLS on various occasions, and took him out on his yacht. RLS dedicated his The Master of Ballantrae (1889) to the couple [54]. On Sir Percy’s eventual death, RLS would eulogise on his sweet nature and “strange, interesting, simple thoughts.…he had the morning dew upon his spirit, so a poet’s son -- to the last” [55].

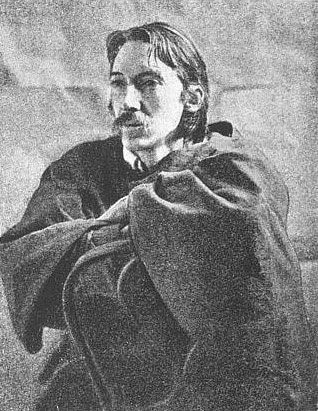

Both Sir Percy and his wife were particularly taken by RLS. They felt he had some sort of connection with Shelley himself. RLS’s conformity to the perceived Shelley ideal would also have been reinforced by his supposed genius, the likelihood of his dying young, and his bohemian ways [56]. Stevenson conformed to many of the indicators of bohemianism – he frequently wore exotic or unconventional clothes, had long hair, dabbled in drugs, enjoyed socialising with artists and literati, and declared himself an atheist dedicated to a life of letters [57].

Sir Percy thought that RLS was mentally like Shelley, and that the poet's spirit lived again in him. He gave RLS a portrait of Shelley’s mother Mary Wollstonecraft as an expression of the idea that she was his “spiritual ancestress”, from whom he inherited a “pedigree of genius” [58]. And for Lady Shelley, the supposed relationship appeared to go even deeper. For one thing, although she had (naturally) never seen Shelley in person, she became convinced that RLS was the physical image of him. Sir Percy took a series of photos of RLS that may have been intended to indulge this fancy, “for the subject is draped in what looks like a cape or blanket, possibly in the 'character’ of the poet” [59] and wears a suitably haunted and Romantic expression (Fig 18).

RLS felt bemused by this “odd controversy”: “I was uneasy at my [claimed] resemblances to Shelley; I seem but a Shelley with less oil and no genius; though I have had the fortune to live longer and (partly) to grow up” [60]. He even goes to the extent of comparing nose shapes, commenting that Shelley’s was “a little turn up nose”, whereas his own was clearly hooked [61].

A rather more significant connection, imaginary or otherwise, became evident when RLS’s mother Mrs Stevenson met Lady Shelley. According to Mrs Stevenson, she had heard that Lady Shelley had called at Skerryvore and was alone, so “went smiling into the room, ready to be adored as the mother of the man her visitor and Sir Percy [had] flattered and praised. But, when she introduced herself, Lady Shelley rose indignantly and turned from her proffered hand. She accused Mrs. Stevenson of having robbed her of a son, for she held Louis should have been sent to her, that he was [Shelley’s] grandson; but by some perverse trickery, of which she judged Mrs. Stevenson guilty, this descendant of Percy Bysshe had come to [the Stevenson’s house] instead of hers at Boscombe Manor”. Lady Shelley, according to Mrs. Stevenson, was firmly convinced that she had been defrauded of a son, and never abated in her animosity towards her for this “robbery” [62].

For Lady Shelley, it seems that in some very real sense RLS performed a dual role as the son she had never had, and as the embodiment of the Shelley spirit. Whether this incident with Mrs Stevenson was some macabre joke [63], a misunderstanding or an exaggeration by Mrs Stevenson is hard to judge, but the degree of delusion seems extraordinary.

And what of Shelley’s heart? in 1889 it found its final resting place when Sir Percy died and was buried with Mary Shelley (along with her parents and Sir Percy's wife Jane). The heart, in a silver urn, accompanied him to the grave [64].

Sir Percy thought that RLS was mentally like Shelley, and that the poet's spirit lived again in him. He gave RLS a portrait of Shelley’s mother Mary Wollstonecraft as an expression of the idea that she was his “spiritual ancestress”, from whom he inherited a “pedigree of genius” [58]. And for Lady Shelley, the supposed relationship appeared to go even deeper. For one thing, although she had (naturally) never seen Shelley in person, she became convinced that RLS was the physical image of him. Sir Percy took a series of photos of RLS that may have been intended to indulge this fancy, “for the subject is draped in what looks like a cape or blanket, possibly in the 'character’ of the poet” [59] and wears a suitably haunted and Romantic expression (Fig 18).

RLS felt bemused by this “odd controversy”: “I was uneasy at my [claimed] resemblances to Shelley; I seem but a Shelley with less oil and no genius; though I have had the fortune to live longer and (partly) to grow up” [60]. He even goes to the extent of comparing nose shapes, commenting that Shelley’s was “a little turn up nose”, whereas his own was clearly hooked [61].

A rather more significant connection, imaginary or otherwise, became evident when RLS’s mother Mrs Stevenson met Lady Shelley. According to Mrs Stevenson, she had heard that Lady Shelley had called at Skerryvore and was alone, so “went smiling into the room, ready to be adored as the mother of the man her visitor and Sir Percy [had] flattered and praised. But, when she introduced herself, Lady Shelley rose indignantly and turned from her proffered hand. She accused Mrs. Stevenson of having robbed her of a son, for she held Louis should have been sent to her, that he was [Shelley’s] grandson; but by some perverse trickery, of which she judged Mrs. Stevenson guilty, this descendant of Percy Bysshe had come to [the Stevenson’s house] instead of hers at Boscombe Manor”. Lady Shelley, according to Mrs. Stevenson, was firmly convinced that she had been defrauded of a son, and never abated in her animosity towards her for this “robbery” [62].

For Lady Shelley, it seems that in some very real sense RLS performed a dual role as the son she had never had, and as the embodiment of the Shelley spirit. Whether this incident with Mrs Stevenson was some macabre joke [63], a misunderstanding or an exaggeration by Mrs Stevenson is hard to judge, but the degree of delusion seems extraordinary.

And what of Shelley’s heart? in 1889 it found its final resting place when Sir Percy died and was buried with Mary Shelley (along with her parents and Sir Percy's wife Jane). The heart, in a silver urn, accompanied him to the grave [64].

7 Conclusion

This is a story of a series of curious coincidences. Physical and psychological transformations, reanimations and reincarnations recur at every turn – in the plots of Mary and RLS’s stories, in Mary’s actual experiences of “death-to-life” events, in the recurrent Shelley-related disinterments, in the afterlife of Shelley’s heart (and of his own reputation) in RLS’ psychological adoption by Shelley’s descendants, with his supposed spiritual links and physical resemblance to Shelley and his supposed status as Lady Shelley’s “stolen” son. In one way or another, these led to the Shelleys’ and RLS’s lives becoming intertwined in an odd combination of life imitating art – and, however imperfectly, of art imitating life.

© Philip McCouat 2017, 2019, 2023. Originally published 2017.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Dr Jekyll, Frankenstein and Shelley's Heart”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

Return to Home

© Philip McCouat 2017, 2019, 2023. Originally published 2017.

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Dr Jekyll, Frankenstein and Shelley's Heart”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

Return to Home

End notes

[1] Genesis 2: 7; 21-22.

[2] Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, Penguin Books, London 1992 (Ed, Maurice Hindle).

[3] Maurice Hindle, Introduction to Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, Penguin Books, London 1992 (revised edn) Introduction at xx. The unseasonal weather in this so-called Year Without a Summer may have been influenced by the colossal and violent eruption of the volcano Mt Tambora, Indonesia, during the previous year. In one of the most powerful eruptions in recorded history, vast amounts of volcanic ash and gases were ejected into the atmosphere. Very likely as a result, there was a sustained cooling of temperatures around the world for many months: Gillen D’Arcy Wood, Tambora, the Eruption that Changed the World, Princeton University Press, 2015.

[4] Richard Holmes, The Age of Wonder, Harper Press, London, 2008, at 327. As to “flirtatious – Claire was a former lover of Byron and was still smitten; Polidori made a play for an uninterested Mary.

[5] Andrew McConnell Stott, The Poet and the Vampyre: the Curse of Byron and the Birth of Literature’s Greatest Monsters, Pegasus, 2014.

[6] Mary Shelley, Preface to 1831 edition.

[7] Many of the issues in the story had been deep concerns of Shelley himself. He evidently made many suggestions, often substantial, in the drafting of the story, and was originally believed to be its author.

[8] These issues are thoroughly considered in Sharon Ruston, “The science of life and death in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein”, https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-science-of-life-and-death-in-mary-shelleys-frankenstein#sthash.7cuxk1wd.dpuf; and Sharon Ruston (2005) “Resurrecting Frankenstein”, The Keats-Shelley Review, 19:1, 97-116; http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1179/ksr.2005.19.1.97?needAccess=true

[9] Hindle, op cit at xiv – xvi.

[10] Ruston, op cit.

[11] Ruston, op cit

[12] Ruston, op cit.

[13] Mary Shelley’s Journal, cited in Hindle, op cit at xix; xxv. Associated with this, considerable interest was shown in the intermediate stages of suspended animation, such as comas, or even fainting or sleeping. In Frankenstein, Mary describes various incidents of fainting or collapse in terms similar to a mini-death, with recovery being likened to a restoration to life. Shelley had also been a frequent sleepwalker since he was a child.

[14] Ruston, op cit.

[15] Daisy Hay, Young Romantics: The Shelleys, Byron and other tangled lives, Bloomsbury, London, 2010, at 84; Ruth Richardson, “Frankenstein: graveyards, scientific experiments and bodysnatchers”: http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/frankenstein-graveyards-scientific-experiments-and-bodysnatchers

[16] Hindle, op cit at xxvii.

[17] Holmes, op cit (Age of Wonder) at 327.

[18] Leigh Hunt, “Account of the death and cremation of Percy Bysshe Shelley, together with a description of his life and character and that of his companion Captain Williams, who was drowned with Shelley in his yacht”, Folios 1-5, transcribed by his wife Marianne https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/account-of-the-death-and-cremation-of-p-b-shelley” MS, 1822, British Library.

[19] Vivian was not found until three weeks later.

[20] Benita Eisler, Byron: child of passion; fool of fame, Penguin Books, Middlesex, 1999, at 707; “Protestant” in this context simply meant non-Catholic.

[21] Roseanne Montillo, The Lady and her Monsters, William Morrow, 2013 at 258.

[22] Edward John Trelawny, The Last Days of Shelley and Byron, 1858; extracted in John Carey (ed), Eyewitness to History, Avon Books, New York, 1987, at 301-2; “Account of the death and cremation of Percy Bysshe Shelley, together with a description of his life and character and that of his companion Captain Williams, who was drowned with Shelley in his yacht”, Folios 7ff, transcribed by Marianne Hunt https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/account-of-the-death-and-cremation-of-p-b-shelley” MS, 1822, British Library.

[23] Trelawny, op cit.

[24] Trelawny, op cit. His accounts of the episode became increasingly elaborate over the years.

[25] Leigh Hunt, op cit.

[26] Trelawny, op cit.

[27] Cited in New York Times 6 August 1955, letter to editor.

[28] Hay, op cit at 267.

[29] Claire Harman, Robert Louis Stevenson: A Biography, Harper Perennial, London, 2006, at 290.

[30] Eisler, op cit at 709.

[31] Various other fragments also were dispersed. Some fragments of his skull are apparently held at the New York Public Library: see Bess Lovejoy,“How Did Bits of Percy Shelley's Skull End Up in the New York Public Library?” 8 July 2013 http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/shelley-skull-fragments-at-nypl; and parts of the jawbone are in an urn in the Keats-Shelley House, along with a lock of his hair.

[32] He married his first wife Harriet when she was 16. He subsequently abandoned her and she later suicided.

[33] Hay, op cit at 254.

[34] Richard Holmes, Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, Penguin Books, London, 1985, at 197; see generally Richard Holmes, Shelley: The Pursuit, NYRB Classics, 2003.

[35] Cited in Richard Holmes, “Death and Destiny”, The Guardian, 24 January 2004 http://www.theguardian.com/books/2004/jan/24/featuresreviews.guardianreview1

[36] Hay, op cit at 300ff.

[37] Hay, op cit at 301.

[38] Hermione Lee, "Shelley's Heart and Pepys's Lobsters," in Virginia’s Woolf’s Nose: Essays on Biography, Princeton University Press, 2005, at 11.

[39] Hay, op cit at 302; Shelley’s Ghost, http://shelleysghost.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/the-shelley-sanctum

[40] Now in the National Portrait Gallery.

[41] Maud Rolleston, Talks with Lady Shelley (published 1925, remembering conversations held in late 1894) http://shelleysghost.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/the-shelley-sanctum

[42] Letter by RLS to PG Hamerton, July 1881, The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, Volume 1 https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Letters_of_Robert_Louis_Stevenson_Volume_1/Chapter_V

[43] Named after a lighthouse in Scotland built by one of RLS’s uncles.

[44] Kidnapped was also written here.

[45] Ian Bell, Dreams of Exile: Robert Louis Stevenson, Mainstream Publishing Company, Edinburgh, 2014, at 191; Greg Buzwell,“ ‘Man is not truly one, but truly two’: duality in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde””: http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/duality-in-robert-louis-stevensons-strange-case-of-dr-jekyll-and-mr-hyde. The famous Whitechapel Ripper murders, which commenced shortly after publication of Jekyll and Hyde, can also be seen in these terms.

[46] Harman, op cit at 301.

[47] Harman, op cit at 289.

[48] Lee Rowland, “To the Manner Re-born”, Dorset Life, Nov 2008 http://www.dorsetlife.co.uk/2008/11/to-the-manor-re-born/

[49] “Men of the Day” series, Vanity Fair 1879.

[50] Rowland, op cit.

[51] Letter by Fanny Stevenson to Sidney Colvin, July 1885, cited in Roger Ingpen, From Shelley In England: New Facts and Letters from the Shelley-Whitton Press (Houghton Mifflin, Boston and New York, 1917.

[52] Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew (eds),The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, Eds Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, Vol V, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995, at 120-21.

[53] Ingpen, op cit.

[54] The dedication reads, “It is my hope that these surroundings of its manufacture may to some degree find favour for my story with seafarers and sea-lovers like yourselves. And at least here is the dedication from a great way off: written by the loud shores of a subtropical island near upon ten thousand miles from Boscombe Chine and Manor: scenes which rise before me as I write, along with the faces and voices of my friends. Well, I am for the sea once more; no doubt Sir Percy also”: RLS, “Dedication”, Waikiki, 17 May 1889, The Master of Ballantrae,, London: Cassell and Co, 1891, p. iii.

[55] Emily W Sunstein, Mary Shelley: Romance and Reality, at 395.

[56] Harman, op cit at 289.

[57] Apart from an early fling with Socialism, however, he was politically on the Conservative side.

[58] Harman, op cit at 289.

[59] Harman, op cit at 290.

[60] RLS letter to Lady Taylor, New Year 1887.

[61] Letter by RLS to WH Low, Jan 1886, The Project Gutenberg Etext of Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson Volume 2 http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/637/pg637.html

[62] [Miss] E Blantyre Simpson. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edinburgh Days, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1914 at 62-4; accessed January 2017 at http://archive.org/stream/louisstevesimprobertrich/louisstevesimprobertrich_djvu.txt

[63] Harman, op cit at 290.

[64] Sunstein, op cit at 395.

© Philip McCouat 2017, 2019,2023

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Dr Jekyll, Frankenstein and Shelley's Heart”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

Return to Home

[2] Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, Penguin Books, London 1992 (Ed, Maurice Hindle).

[3] Maurice Hindle, Introduction to Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, Penguin Books, London 1992 (revised edn) Introduction at xx. The unseasonal weather in this so-called Year Without a Summer may have been influenced by the colossal and violent eruption of the volcano Mt Tambora, Indonesia, during the previous year. In one of the most powerful eruptions in recorded history, vast amounts of volcanic ash and gases were ejected into the atmosphere. Very likely as a result, there was a sustained cooling of temperatures around the world for many months: Gillen D’Arcy Wood, Tambora, the Eruption that Changed the World, Princeton University Press, 2015.

[4] Richard Holmes, The Age of Wonder, Harper Press, London, 2008, at 327. As to “flirtatious – Claire was a former lover of Byron and was still smitten; Polidori made a play for an uninterested Mary.

[5] Andrew McConnell Stott, The Poet and the Vampyre: the Curse of Byron and the Birth of Literature’s Greatest Monsters, Pegasus, 2014.

[6] Mary Shelley, Preface to 1831 edition.

[7] Many of the issues in the story had been deep concerns of Shelley himself. He evidently made many suggestions, often substantial, in the drafting of the story, and was originally believed to be its author.

[8] These issues are thoroughly considered in Sharon Ruston, “The science of life and death in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein”, https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-science-of-life-and-death-in-mary-shelleys-frankenstein#sthash.7cuxk1wd.dpuf; and Sharon Ruston (2005) “Resurrecting Frankenstein”, The Keats-Shelley Review, 19:1, 97-116; http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1179/ksr.2005.19.1.97?needAccess=true

[9] Hindle, op cit at xiv – xvi.

[10] Ruston, op cit.

[11] Ruston, op cit

[12] Ruston, op cit.

[13] Mary Shelley’s Journal, cited in Hindle, op cit at xix; xxv. Associated with this, considerable interest was shown in the intermediate stages of suspended animation, such as comas, or even fainting or sleeping. In Frankenstein, Mary describes various incidents of fainting or collapse in terms similar to a mini-death, with recovery being likened to a restoration to life. Shelley had also been a frequent sleepwalker since he was a child.

[14] Ruston, op cit.

[15] Daisy Hay, Young Romantics: The Shelleys, Byron and other tangled lives, Bloomsbury, London, 2010, at 84; Ruth Richardson, “Frankenstein: graveyards, scientific experiments and bodysnatchers”: http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/frankenstein-graveyards-scientific-experiments-and-bodysnatchers

[16] Hindle, op cit at xxvii.

[17] Holmes, op cit (Age of Wonder) at 327.

[18] Leigh Hunt, “Account of the death and cremation of Percy Bysshe Shelley, together with a description of his life and character and that of his companion Captain Williams, who was drowned with Shelley in his yacht”, Folios 1-5, transcribed by his wife Marianne https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/account-of-the-death-and-cremation-of-p-b-shelley” MS, 1822, British Library.

[19] Vivian was not found until three weeks later.

[20] Benita Eisler, Byron: child of passion; fool of fame, Penguin Books, Middlesex, 1999, at 707; “Protestant” in this context simply meant non-Catholic.

[21] Roseanne Montillo, The Lady and her Monsters, William Morrow, 2013 at 258.

[22] Edward John Trelawny, The Last Days of Shelley and Byron, 1858; extracted in John Carey (ed), Eyewitness to History, Avon Books, New York, 1987, at 301-2; “Account of the death and cremation of Percy Bysshe Shelley, together with a description of his life and character and that of his companion Captain Williams, who was drowned with Shelley in his yacht”, Folios 7ff, transcribed by Marianne Hunt https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/account-of-the-death-and-cremation-of-p-b-shelley” MS, 1822, British Library.

[23] Trelawny, op cit.

[24] Trelawny, op cit. His accounts of the episode became increasingly elaborate over the years.

[25] Leigh Hunt, op cit.

[26] Trelawny, op cit.

[27] Cited in New York Times 6 August 1955, letter to editor.

[28] Hay, op cit at 267.

[29] Claire Harman, Robert Louis Stevenson: A Biography, Harper Perennial, London, 2006, at 290.

[30] Eisler, op cit at 709.

[31] Various other fragments also were dispersed. Some fragments of his skull are apparently held at the New York Public Library: see Bess Lovejoy,“How Did Bits of Percy Shelley's Skull End Up in the New York Public Library?” 8 July 2013 http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/shelley-skull-fragments-at-nypl; and parts of the jawbone are in an urn in the Keats-Shelley House, along with a lock of his hair.

[32] He married his first wife Harriet when she was 16. He subsequently abandoned her and she later suicided.

[33] Hay, op cit at 254.

[34] Richard Holmes, Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, Penguin Books, London, 1985, at 197; see generally Richard Holmes, Shelley: The Pursuit, NYRB Classics, 2003.

[35] Cited in Richard Holmes, “Death and Destiny”, The Guardian, 24 January 2004 http://www.theguardian.com/books/2004/jan/24/featuresreviews.guardianreview1

[36] Hay, op cit at 300ff.

[37] Hay, op cit at 301.

[38] Hermione Lee, "Shelley's Heart and Pepys's Lobsters," in Virginia’s Woolf’s Nose: Essays on Biography, Princeton University Press, 2005, at 11.

[39] Hay, op cit at 302; Shelley’s Ghost, http://shelleysghost.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/the-shelley-sanctum

[40] Now in the National Portrait Gallery.

[41] Maud Rolleston, Talks with Lady Shelley (published 1925, remembering conversations held in late 1894) http://shelleysghost.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/the-shelley-sanctum

[42] Letter by RLS to PG Hamerton, July 1881, The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, Volume 1 https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Letters_of_Robert_Louis_Stevenson_Volume_1/Chapter_V

[43] Named after a lighthouse in Scotland built by one of RLS’s uncles.

[44] Kidnapped was also written here.

[45] Ian Bell, Dreams of Exile: Robert Louis Stevenson, Mainstream Publishing Company, Edinburgh, 2014, at 191; Greg Buzwell,“ ‘Man is not truly one, but truly two’: duality in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde””: http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/duality-in-robert-louis-stevensons-strange-case-of-dr-jekyll-and-mr-hyde. The famous Whitechapel Ripper murders, which commenced shortly after publication of Jekyll and Hyde, can also be seen in these terms.

[46] Harman, op cit at 301.

[47] Harman, op cit at 289.

[48] Lee Rowland, “To the Manner Re-born”, Dorset Life, Nov 2008 http://www.dorsetlife.co.uk/2008/11/to-the-manor-re-born/

[49] “Men of the Day” series, Vanity Fair 1879.

[50] Rowland, op cit.

[51] Letter by Fanny Stevenson to Sidney Colvin, July 1885, cited in Roger Ingpen, From Shelley In England: New Facts and Letters from the Shelley-Whitton Press (Houghton Mifflin, Boston and New York, 1917.

[52] Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew (eds),The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, Eds Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, Vol V, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995, at 120-21.

[53] Ingpen, op cit.

[54] The dedication reads, “It is my hope that these surroundings of its manufacture may to some degree find favour for my story with seafarers and sea-lovers like yourselves. And at least here is the dedication from a great way off: written by the loud shores of a subtropical island near upon ten thousand miles from Boscombe Chine and Manor: scenes which rise before me as I write, along with the faces and voices of my friends. Well, I am for the sea once more; no doubt Sir Percy also”: RLS, “Dedication”, Waikiki, 17 May 1889, The Master of Ballantrae,, London: Cassell and Co, 1891, p. iii.

[55] Emily W Sunstein, Mary Shelley: Romance and Reality, at 395.

[56] Harman, op cit at 289.

[57] Apart from an early fling with Socialism, however, he was politically on the Conservative side.

[58] Harman, op cit at 289.

[59] Harman, op cit at 290.

[60] RLS letter to Lady Taylor, New Year 1887.

[61] Letter by RLS to WH Low, Jan 1886, The Project Gutenberg Etext of Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson Volume 2 http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/637/pg637.html

[62] [Miss] E Blantyre Simpson. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edinburgh Days, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1914 at 62-4; accessed January 2017 at http://archive.org/stream/louisstevesimprobertrich/louisstevesimprobertrich_djvu.txt

[63] Harman, op cit at 290.

[64] Sunstein, op cit at 395.

© Philip McCouat 2017, 2019,2023

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “Dr Jekyll, Frankenstein and Shelley's Heart”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

Return to Home