Early influences of photography on art - Part 2

|

By Philip McCouat Pt 1: Initial impacts Pt 2: Photography as a working aid Pt 3: Photographic effects Pt 4: New approaches to “reality” |

More on photography

For other articles on photography, see: Art in a speeded-up world Why wasn’t photography invented earlier? ---------------------------------------------- |

Photography as a working aid

_ When Daguerre’s invention was officially unveiled, it was predicted that “the process will afford [painters] a quick and easy method of forming collections of sketches and drawings, which they would not be able to procure, unless they were to spend much time and trouble in doing them with their own hand, and even then they would be far less perfect” [34]. As we shall see, events were to prove this prediction substantially correct [35].

Some artists were prepared to openly concede their use of photographs, but typically stressed that it was an ancillary medium. This, for example, was Delacroix’s position, as stated in his essay On the art of dreaming [36]. Others, rather touchy on the issue, described photography’s subsidiary role in terms that were almost comically dismissive. Meissonnier, for example, said he used photos “as Moliere consulted his servants” [37]. Similarly, Baudelaire said that photography’s real task was in being the servant of science and art, but “a very humble servant like typography or stenography which have neither created nor improved literature”[38].

These “servants” took many forms – photographs of other artists’ artworks, of one’s own artworks, photographs taken of specific subjects for paintings, postcards and cartes de visite. Other types of commercial photographic resources also started to become available. In Paris, for example, galleries and shops began marketing large catalogues of photographs, described as “études d’après nature”, or “documents pour artistes” [38a]. Often specifically commissioned [39], these covered an enormous range – a virtual mail order catalogue of the world – including artfully posed female nudes, peasants, animals, landscapes, architecture and scenes from foreign lands. Many painters became enthusiastic collectors, with some possessing thousands [40].

Some artists were prepared to openly concede their use of photographs, but typically stressed that it was an ancillary medium. This, for example, was Delacroix’s position, as stated in his essay On the art of dreaming [36]. Others, rather touchy on the issue, described photography’s subsidiary role in terms that were almost comically dismissive. Meissonnier, for example, said he used photos “as Moliere consulted his servants” [37]. Similarly, Baudelaire said that photography’s real task was in being the servant of science and art, but “a very humble servant like typography or stenography which have neither created nor improved literature”[38].

These “servants” took many forms – photographs of other artists’ artworks, of one’s own artworks, photographs taken of specific subjects for paintings, postcards and cartes de visite. Other types of commercial photographic resources also started to become available. In Paris, for example, galleries and shops began marketing large catalogues of photographs, described as “études d’après nature”, or “documents pour artistes” [38a]. Often specifically commissioned [39], these covered an enormous range – a virtual mail order catalogue of the world – including artfully posed female nudes, peasants, animals, landscapes, architecture and scenes from foreign lands. Many painters became enthusiastic collectors, with some possessing thousands [40].

Assistance with portraits

Despite some early problems with quality, long exposure times and the resultant rigid poses, photographs assumed a particular importance as aids in portrait painting.

During the eighteenth century, although about three sittings were normal for many painted portraits [41], stories of many more extended and traumatic sitting experiences had became legendary. Sir Thomas Lawrence, who had long dallied over a portrait of an Earl’s wife and baby son, tried to reassure the Earl that he only needed one more sitting “to finish the baby”. The Earl reputedly replied, “That’s all very well, but the baby’s in the Guards now” [42]. Ingres took twelve years to finish his portrait of Mme Moitessier. Cezanne, while painting Ambroise Vollard, shouted, “You’ve spoiled the pose! Do I have to tell you again you must sit like an apple. Does an apple move?” The painting was abandoned after multiple sittings [43]. The young woman who modelled for Millais’ Ophelia was required to simulate drowning for session after session, as a result of which she caught a severe cold and her father threatened to sue [44].

Of course, depending on the procedure involved, there could also be delays with photography itself. The prolific German portraitist Franz van Lenbach arranged for dozens of photos of Chancellor Bismarck to be taken for his portrait, which ultimately (and not surprisingly) was criticised for its glassy gaze [45]. Nevertheless, as photographs were capable of undeniable accuracy and were generally so much quicker to process, the English portraitist Sickert commented that, after photography, it was “sadism” to require more than one sitting [46].

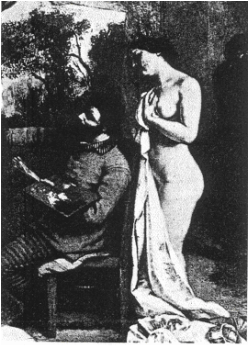

Examples of artists that used photographs for this purpose included Delacroix, Cézanne, Toulouse-Lautrec, G F Watts [47], Munch (for commissioned works)[48], Eakins, Alphonse Mucha (fig 1C), the Swede Anders Zorn and possibly Ingres [49]. Courbet, who was attracted to the modernity, social grittiness and realism of photography, admitted using a stock photographic nude study for The Artist’s Studio (1855) (Figs 1A and 1B)[50] and various other figures in that painting are also based on photographs. Of course, using photography in this way, even for formal works, did not imply that the painted versions were simply copies. Courbet typically gave his paintings a more tactile physical quality by means of the thickness with which he applied colour and the “crudeness” of his brushwork [51]. Similarly, Eakins’ portraits, such as The Writing Master (1882) were significantly more tactile, intense and atmospheric than their acknowledged photographic sources.

During the eighteenth century, although about three sittings were normal for many painted portraits [41], stories of many more extended and traumatic sitting experiences had became legendary. Sir Thomas Lawrence, who had long dallied over a portrait of an Earl’s wife and baby son, tried to reassure the Earl that he only needed one more sitting “to finish the baby”. The Earl reputedly replied, “That’s all very well, but the baby’s in the Guards now” [42]. Ingres took twelve years to finish his portrait of Mme Moitessier. Cezanne, while painting Ambroise Vollard, shouted, “You’ve spoiled the pose! Do I have to tell you again you must sit like an apple. Does an apple move?” The painting was abandoned after multiple sittings [43]. The young woman who modelled for Millais’ Ophelia was required to simulate drowning for session after session, as a result of which she caught a severe cold and her father threatened to sue [44].

Of course, depending on the procedure involved, there could also be delays with photography itself. The prolific German portraitist Franz van Lenbach arranged for dozens of photos of Chancellor Bismarck to be taken for his portrait, which ultimately (and not surprisingly) was criticised for its glassy gaze [45]. Nevertheless, as photographs were capable of undeniable accuracy and were generally so much quicker to process, the English portraitist Sickert commented that, after photography, it was “sadism” to require more than one sitting [46].

Examples of artists that used photographs for this purpose included Delacroix, Cézanne, Toulouse-Lautrec, G F Watts [47], Munch (for commissioned works)[48], Eakins, Alphonse Mucha (fig 1C), the Swede Anders Zorn and possibly Ingres [49]. Courbet, who was attracted to the modernity, social grittiness and realism of photography, admitted using a stock photographic nude study for The Artist’s Studio (1855) (Figs 1A and 1B)[50] and various other figures in that painting are also based on photographs. Of course, using photography in this way, even for formal works, did not imply that the painted versions were simply copies. Courbet typically gave his paintings a more tactile physical quality by means of the thickness with which he applied colour and the “crudeness” of his brushwork [51]. Similarly, Eakins’ portraits, such as The Writing Master (1882) were significantly more tactile, intense and atmospheric than their acknowledged photographic sources.

Although photographs were typically used primarily as aides-memoires, their use also went considerably further. Lenbach typically used three alternative methods – he had the heads of the photographs enlarged to copy them; he had slides made from the images which were then projected onto the canvas for tracing; and he used the method of “photo-peinture” to create a sensitised canvas with a faint image of the portrait, over which he painted his picture [52].

Even where delays were not a factor, using purchased cartes or photographs would typically be cheaper than hiring models, who could often behave unsatisfactorily in any event [53]. The handsome prices charged by shearers for posing time evidently motivated Australian artist Tom Roberts to take photographs of woolsheds and create composite images for Shearing the Rams (1890) [54].

Even where delays were not a factor, using purchased cartes or photographs would typically be cheaper than hiring models, who could often behave unsatisfactorily in any event [53]. The handsome prices charged by shearers for posing time evidently motivated Australian artist Tom Roberts to take photographs of woolsheds and create composite images for Shearing the Rams (1890) [54].

Difficult or sensitive works

Photographs could also be particularly useful for portraits or other works when the subject matter was difficult or sensitive. This could apply, for example, where popularly-recognisable identities were involved. For example, at Queen Victoria’s own suggestion, Landseer copied Queen Victoria, John Brown and two of her Daughters from a commissioned photograph. Degas’ portrait of Princess Metternich was based on a photograph, as she never actually posed [55]. Manet literally transcribed specific photos in paintings such as his portrait of Faure in the role of Hamlet, even though the subject had previously had over 30 sittings [56].

This could particularly apply where large numbers, particularly of notables, were involved. D.O. Hill explicitly based his The Disruption of 1843 on photographs so that he could capture the identities of the 400 people who crowded the scene – a task that would have been virtually impossible otherwise [57]. Similarly, G F Watts used photographs for his “Hall of Fame” portraits for the National Portrait Gallery, and Tom Roberts used photographs of otherwise-unavailable royalty in his Opening of the First Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia (1903) [58].

In cases of arranged marriages, photographs generally replaced the painted or drawn portraits that were typically exchanged by the prospective partners. The same sometimes applied with official portraits. Of course, the flattery afforded by painting was sometimes considered to outweigh considerations of accuracy. For example, in 1889 the official photographic portrait of the Japanese emperor was replaced by a lithograph of a drawn portrait by the Italian artist Chiossone, which provided a more imposing, handsome, dignified and stately appearance.

Photographs were also commonly used wherethe subject was dead [59], absent, impatient, or otherwise unavailable. So, for example, a busy Cecil Rhodes wrote to his portraitist “I have sent photographs to your house, so you can begin on Tuesday without me”[60]. Eakins used photos for his portrait of ethnographer Cushing, as the subject was too ill to stand for long periods in costume. Photographs also could be useful for portraits that were set in the past, for example in depictions of persons as they were in childhood [61] and, once exposure times came down, for portraits of fidgety children [62]. They were even used as permanent records to promote artworks made from perishable matter, such as the butter sculptures of the American artist Caroline S Brooks [62A].

Photographs also made it easier for unusual or uncomfortable poses to be captured. For example, Degas probably based the uncomfortably contorted pose of Woman Drying Herself on a similarly-posed photograph that was found in his studio after his death [62B]. They also enabled painters to physically position themselves in more imaginative ways. Thus, even to execute a sketch for Cassatt’s Boating Party (Fig 2), the artist would presumably have had to be half-crouching in an extremely inconvenient and unbalanced position behind the rower [63]. Photographs could also be usefulfor painters with failing eyesight [64].

This could particularly apply where large numbers, particularly of notables, were involved. D.O. Hill explicitly based his The Disruption of 1843 on photographs so that he could capture the identities of the 400 people who crowded the scene – a task that would have been virtually impossible otherwise [57]. Similarly, G F Watts used photographs for his “Hall of Fame” portraits for the National Portrait Gallery, and Tom Roberts used photographs of otherwise-unavailable royalty in his Opening of the First Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia (1903) [58].

In cases of arranged marriages, photographs generally replaced the painted or drawn portraits that were typically exchanged by the prospective partners. The same sometimes applied with official portraits. Of course, the flattery afforded by painting was sometimes considered to outweigh considerations of accuracy. For example, in 1889 the official photographic portrait of the Japanese emperor was replaced by a lithograph of a drawn portrait by the Italian artist Chiossone, which provided a more imposing, handsome, dignified and stately appearance.

Photographs were also commonly used wherethe subject was dead [59], absent, impatient, or otherwise unavailable. So, for example, a busy Cecil Rhodes wrote to his portraitist “I have sent photographs to your house, so you can begin on Tuesday without me”[60]. Eakins used photos for his portrait of ethnographer Cushing, as the subject was too ill to stand for long periods in costume. Photographs also could be useful for portraits that were set in the past, for example in depictions of persons as they were in childhood [61] and, once exposure times came down, for portraits of fidgety children [62]. They were even used as permanent records to promote artworks made from perishable matter, such as the butter sculptures of the American artist Caroline S Brooks [62A].

Photographs also made it easier for unusual or uncomfortable poses to be captured. For example, Degas probably based the uncomfortably contorted pose of Woman Drying Herself on a similarly-posed photograph that was found in his studio after his death [62B]. They also enabled painters to physically position themselves in more imaginative ways. Thus, even to execute a sketch for Cassatt’s Boating Party (Fig 2), the artist would presumably have had to be half-crouching in an extremely inconvenient and unbalanced position behind the rower [63]. Photographs could also be usefulfor painters with failing eyesight [64].

Exotica

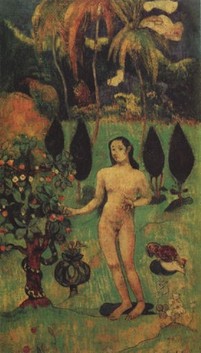

Photographs by others were particularly helpful as resources for painters of exotica, such as the Orientalists [65], especially if they were impoverished stay-at-homes, such as Henri Rousseau [66]; romantic painters such as Alma-Tadema [67] or overseas expatriates such as Gauguin, whose huge library of what he called his “entire little world of friends” – photographs, postcards and reproductions – acted as source material and inspiration, and kept him in touch with what was happening at home [68]. Like many other artists, his use of these sources was extremely creative. For example, his Exotic Eve (1894) appears to have been generated from the grafting of the youthful head from a portrait of this mother (in turn based on a photograph), to the body of a sensuous nude from a photograph of a temple decoration (Figs 3 and 4) [69]. Often, Gauguin actually preferred to obtain photographs of native art rather than go to the effort of going to witness it himself, even when it was close at hand [70].

The demand for exotica prompted professional photo studies in Egypt and Algeria to produce études specifically on oriental themes for painters. British artist William Simpson explicitly recorded in his notebook the drawings he made and the cartes that he used to create them [71]. The American artist/writer Edwin Lord Weeks used photographs of his Asian travels extensively in his paintings. Artists such as Gerome, Seddon and Holman Hunt also directly collaborated with photographers in mounting joint overseas expeditions [72]. For these artists, this was not just a matter of obtaining material, but also of ensuring precision and, possibly, satisfying their need to approximate photography’s claim of unarguably having “been there”[73]. Others were less purely motivated – Rossetti overcame his publicly-expressed scruples by requesting friends to send him stereoscopic photos of cityscapes, as he wanted to use them in “painting Troy at the back of my Helen”[74].

Where precision was important

Photography was also invaluable in capturing motifs such as highly detailed architectural elements [75], or subjects such as foliage or the folds in draping in clothes, which could easily alter during a normal sitting. Theodore Robinson, who used photography extensively, said that painting directly from nature was difficult as things do not remain the same, and the camera helped to retain the picture in the artist’s eye [76]. Photographs were therefore useful in capturing particularly transitory or momentary elements such as clouds, waves [76a] or even lightning [76b]. Similarly, it was useful in recording anatomical details [77] and the subtleties of facial expressions [78]. Photographs were also used to train one’s hand at drawing [79] and, because of their precision, partly displaced the painted images previously used in scientific or botanical studies.

Photography’s perceived accuracy also meant that it assumed an important role as a recorder of contemporary events, such as historical events or wars. Particularly when photographers stopped setting up staged settings and were able to get closer to the action, the impact was dramatic – Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote of the profound shock he received at seeing photographs of the war dead for the first time [80]. To Holmes, these images were so powerful they were almost like the corpses themselves.

War photographs started to become used as resources for painters such as Augustus Egg, who used Fenton’s photos of the Crimean War to check accuracy. In Manet’s Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1867), the artist used photographs of details such as the bloodstained shirt, resulting in an effective mixture of photographic accuracy with painterly freedom [81]. The anti-heroic realism of Winslow Homer’s Sharpshooter (1863) is hardly surprising, given that some of his early painting was based on drawn versions of American Civil War photographs [82].

In a more general sense, the uncompromisingly graphic nature of many of those Civil War photos made it harder for some viewers to accept the glorious and heroic battle scenes that had been popular earlier in the century [83]. However, photography did not become a viable rival to heroic battle painting till closer to the 20th century, when techniques and equipment had improved sufficiently to enable photos to be taken of actual massed combat, as distinct from post-combat or individual scenes [84].

Photography’s perceived accuracy also meant that it assumed an important role as a recorder of contemporary events, such as historical events or wars. Particularly when photographers stopped setting up staged settings and were able to get closer to the action, the impact was dramatic – Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote of the profound shock he received at seeing photographs of the war dead for the first time [80]. To Holmes, these images were so powerful they were almost like the corpses themselves.

War photographs started to become used as resources for painters such as Augustus Egg, who used Fenton’s photos of the Crimean War to check accuracy. In Manet’s Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1867), the artist used photographs of details such as the bloodstained shirt, resulting in an effective mixture of photographic accuracy with painterly freedom [81]. The anti-heroic realism of Winslow Homer’s Sharpshooter (1863) is hardly surprising, given that some of his early painting was based on drawn versions of American Civil War photographs [82].

In a more general sense, the uncompromisingly graphic nature of many of those Civil War photos made it harder for some viewers to accept the glorious and heroic battle scenes that had been popular earlier in the century [83]. However, photography did not become a viable rival to heroic battle painting till closer to the 20th century, when techniques and equipment had improved sufficiently to enable photos to be taken of actual massed combat, as distinct from post-combat or individual scenes [84].

Photographs of artworks

Many painters also used photographs of their own works as working aids, either as documentation [85], or for commercial resale. In Paris, the dealer Eugene Druet set up business as an artist's photographer. Courbet routinely had photographs made of his major pictures and sold them both to promote the work and to generate additional income beyond the sale price of a single painting. Later he sold the rights to photographic reproduction of certain works [86]. Resale became a “common source of income” for artists from 1860 onwards [87].

Ingres had his pictures photographed so that he could use them to teach his students while the original was being exhibited elsewhere. Later, Picasso would commonly photograph his works as they progressed, feeling that it helped to remind him of the essential nature of the original vision [88]. Having oneself photographed, often in the artist’s own studio, also became common [89], particularly with assiduous self promoters such as Courbet [90].

Probably more importantly, photographic reproduction also provided access to other people’s artistic creations. Before photography, painters or anyone else wanting access to the art works of old masters or foreign painters had largely been limited to engraved reproductions. With the development of photography, publishers such as Alinari began to build up massive photo libraries of art works from all round the world, greatly improving both the quality and availability of art works from which painters could copy, and learn or refine their craft. Mass distribution of artworks in books also led to greater interest by the public, potentially building a more visually educated audience. In Malraux’s terms, this contributed to the creation of a super museum, a “museum without walls” [91].

There were, however, warnings that the spread of popular and inexpensive photographs could run the risk of making art banal, and that seeing only a reproduction detracted from the genuine artistic experience [92]. Walter Benjamin noted that the increased availablility and accessibility meant that the public did not have the benefit of “hierarchical mediation” which would enable them to understand and appreciate new experiences and directions in art. Benjamin also argued that even the best reproduction lacked an original painting’s “aura” – the sense of its unique existence “at the place it happens to be”. This was particularly so where photographs of artworks altered the scale (as they often did), isolated details or reduced the chromatism of the original [93].

While these are valid cautions, reproduction did have had some undeniable benefits. The very demystification and fragmentation that it created was capable of inspiring new insights or spurs to creativity. Picasso, for example, would later obtain intense creative excitement from manipulation of this sort – Baldassari cites how Picasso created a sketch based on a rotated Alinari photograph of da Vinci’s Adoration of the Magi [94]. In a more general sense, is also arguable that this enormous expansion of the virtual museum, coupled with the contemporaneous development of public art galleries, had the effect of enlarging Western artists’ concepts of what constituted “art”. Together with the increasing opportunity for individuality that flowed from the decline in patronage, in commissioning and in the apprentice system, it is likely that artists therefore became more free – whether willingly or not – in the ways in which they could express themselves [95].

Photographic reproduction also greatly facilitated academic study and comparisons, and the analysis of trends and styles [96], thus contributing to the creation of art history as a discipline – a development which (one trusts) also had trickle-down benefits to sections of the art public.

Go now to Part 3 "Photographic effects" for the impact that photography had on the works that artists produced

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2018

We welcome your comments on this article

Ingres had his pictures photographed so that he could use them to teach his students while the original was being exhibited elsewhere. Later, Picasso would commonly photograph his works as they progressed, feeling that it helped to remind him of the essential nature of the original vision [88]. Having oneself photographed, often in the artist’s own studio, also became common [89], particularly with assiduous self promoters such as Courbet [90].

Probably more importantly, photographic reproduction also provided access to other people’s artistic creations. Before photography, painters or anyone else wanting access to the art works of old masters or foreign painters had largely been limited to engraved reproductions. With the development of photography, publishers such as Alinari began to build up massive photo libraries of art works from all round the world, greatly improving both the quality and availability of art works from which painters could copy, and learn or refine their craft. Mass distribution of artworks in books also led to greater interest by the public, potentially building a more visually educated audience. In Malraux’s terms, this contributed to the creation of a super museum, a “museum without walls” [91].

There were, however, warnings that the spread of popular and inexpensive photographs could run the risk of making art banal, and that seeing only a reproduction detracted from the genuine artistic experience [92]. Walter Benjamin noted that the increased availablility and accessibility meant that the public did not have the benefit of “hierarchical mediation” which would enable them to understand and appreciate new experiences and directions in art. Benjamin also argued that even the best reproduction lacked an original painting’s “aura” – the sense of its unique existence “at the place it happens to be”. This was particularly so where photographs of artworks altered the scale (as they often did), isolated details or reduced the chromatism of the original [93].

While these are valid cautions, reproduction did have had some undeniable benefits. The very demystification and fragmentation that it created was capable of inspiring new insights or spurs to creativity. Picasso, for example, would later obtain intense creative excitement from manipulation of this sort – Baldassari cites how Picasso created a sketch based on a rotated Alinari photograph of da Vinci’s Adoration of the Magi [94]. In a more general sense, is also arguable that this enormous expansion of the virtual museum, coupled with the contemporaneous development of public art galleries, had the effect of enlarging Western artists’ concepts of what constituted “art”. Together with the increasing opportunity for individuality that flowed from the decline in patronage, in commissioning and in the apprentice system, it is likely that artists therefore became more free – whether willingly or not – in the ways in which they could express themselves [95].

Photographic reproduction also greatly facilitated academic study and comparisons, and the analysis of trends and styles [96], thus contributing to the creation of art history as a discipline – a development which (one trusts) also had trickle-down benefits to sections of the art public.

Go now to Part 3 "Photographic effects" for the impact that photography had on the works that artists produced

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2018

We welcome your comments on this article

End Notes for Part 2

34. Quoted in Goldberg, V, “A handmaiden, time saver and occasional rival” in New York Times, 20 December 1996.

35. Millais even remarked that all artists were using photographs, but this is certainly exaggerated (Vaizey, op cit at 21).

36. Koetzle, op cit at 35.

37. Vaizey, op cit at 26.

38. Johnson, op cit at 81. Photographer Oscar Rejlander expressed the relationship quite tactfully in his self-explanatory study Infant Photography Gives Painter an Additional Brush (1856).

38a. For example, in England, the London Stereoscopic Company regularly advertised “100,000 charming stereoscopic views from all parts of the world, and groups of figures representing almost every incident in human life, from 6 shillings per doz”.

39. For example, in 1870, the well-known publisher, editor and seller of photographs, Auguste Giraudon, announced that he had commissioned a painter to do a series of photographic studies of peasants at work in the forest near Barbizon. The results were to be sold to artists to be used as generating images for their own efforts. The tradition of providing "documents for artists" was later carried on by photographers such as Eugene Atget, with his atmospheric photographs of turn-of-the-century Paris.

40. When Corot died, hundreds of photographs were found in his studio. The American heroic landscapist Frederick Church had some 4,000 photographs from all round the world, including vines, ferns waterfalls and palms, and clouds under varying conditions and at different times of the day. Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema had over 5,000. Delacroix had an album of photographic studies, which he called his “treasures”. Moreau had hundreds. Courbet and Millet collected many photographs for reference in painting light and shading. Later, Picasso would collect thousands of art reproduction, ethnographic postcards, regional photographs (Baldassart, A, “Picasso 1901-06: Painting in the Mirror of the Photograph” in Kosinski, D, (ed) The Artist and the Camera: Degas to Picasso, Dallas Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2000, at 289).

41. Campbell, L, “Time and the Portrait” in Lippincott, op cit at 190. In contrast, Van Dyke reputedly worked at exceptional speed, with individual sittings limited to one hour, and up to 14 sittings a day.

42. Campbell, op cit at 190. The Earl was exaggerating slightly – the portrait was eventually exhibited in 1821 when the child was 11.

43. McPherson, H, The Modern Portrait in Nineteenth Century France, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001, at 1.

44. Hughes, R, Nothing If Not Critical, The Harvill Press, London, 1995 at 116. The young woman was Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal.

45. Vaizey, op cit at 28.

46. Sickert’s own practice was to paint the rough outline of the sitter’s likeness and form onto the canvas, in what seemed to him a characteristic pose. He then had the sitter photographed in the same pose and worked thereafter from the photograph (Baron, W, Sickert, Phaidon, 1973).

47. For example, in 1873 Watts asked sitter Sir Charles Dilke to “bring some good photographs. They help to make my acquaintance with peculiarity and shorten the sittings necessary” (Maas, op cit at 200).

48. Eggum, op cit.

49. The evidence includes: (1) Ingres’ undoubted interest in photography, and the use of it to record his own works; (2) the lateral reversal of the image from earlier studies; (3) the pose of hand to chin, which recalls the photographic convention that had developed to enabler sitters to support their heads; (4) the cropping of the edges; and (5) the silvery metallic appearance, which contrasted with Ingres’ earlier works

50. Various other figures in that painting are also based on photographs. Letters survive which indicate his broad ranging requests to friends and other photographers for images (Vaizey, op cit at 21).

51. Photographs also could not rival the heroic size of many of Courbet’s canvases.

52. Muysers, C, “Physiology and Photography: The Evolution of Franz von Lenbach’s Portraiture”, Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide, Vol 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2002 (www.19thc-artworldwide.org, accessed January 2010).

53. Jacobsen, op cit at 72.

54. Gaskins, op cit at 344, 369.

55. Vaizey, op cit at 44.

56. McCauley, op cit at 172.

57. He actually reconstructed the scene by getting participants to pose for 182 photos and did the painting 18 years after the event (Gaskins, op cit at 317). Similarly, William Powell Firth used photographs to capture the complex, crowded scenes of Derby Day (1858).

58. Snapshots he took of other notables for this purpose were not successful (Gaskins, op cit at 317). A folksy American example is provided by Cornelia Adele Fassett, who used photographs in her painting The Florida Case before the Electoral Commission (1879), which included over 250 portraits, some of which are based on photographic portraits by Matthew Brady (http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/art/artifact/Painting_33_00006.htm, accessed Jan 2010; United States Senate Catalogue of Fine Art, p 122ff)).

59. For example, Australia’s first locally trained artist William Dowling painted the late father of his patron William Robertson from a photograph (“Masterpieces from the Nation Fund”, artonview 61 Autumn 1010 NGA p 4). Matisse made four posthumous drawings of his sister in law from photographs (Gilot, F, Matisse and Picasso: A Friendship in Art, Doubleday, 1990 at 179).

60. Rideal, L,“The Developing Portrait – Painting Towards Photography”, National Portrait Gallery, www.npg.org/uk, consulted January 2010.

61. For example, Thomas le Clear’s Interior with Portraits, discussed earlier.

62. For example, Renoir’s portrait of a young girl in Mlle Romaire Lacaux (1864) shares the pose, lighting, and psychological moment it portrays with a carte of an unidentified figure by Disderi (McCauley, op cit at 200).

62A. Pamela Simpson, Corn Palaces and Butter Queens: A History of Crop Art and Dairy Sculpture, University of Minnesota Press, 2012, at 143.

62B. Though Degas was not averse to requiring his female models to endure long periods of severe discomfort in holding difficult poses.

63. A similar point could be made about Caillebotte’s The Oarsmen (1872). Both these paintings also exhibit other photographic elements such as close-ups and cut-off foregrounds: see later discussion.

64. Degas is an obvious example, though the degree to which the use of photographs actually influenced his painting is problematic: see later discussion. The Dutch painter Bakker-Korff temporarily gave up painting because of failing eyesight, but in 1859 started painting small-scale, realistic genre scenes based on photographs. See generally Trevor-Roper, T, The world through blunted sight: An inquiry into the influence of defective vision on art and character, Bobbs-Merrill, New York, 1970. As a modern example, Balthus adjusted his working style from drawing to photography in order to compensate for a loss of precision resulting from old age and illness.

65. Some critics argued thatthe Pre-Raphaelites in fact relied too much on photographs, citing for example the close similarities between Seddon’s Jerusalem and the Valley from the Hill of Evil Counsel (1854) from photos taken on site (Scharf, op cit at 102). In this particular case, the criticism seems harsh – Seddon had spent 120 extremely uncomfortable days doing the painting on site and used the photograph only to finish off in the studio.

66. Hughes (Critical), op cit at 141.

67. This artist had 150 volumes of photographs which he described as being of the “greatest use” to painters (Vaizey, op cit at 20); Ulrich Pohlmann, "Alma-Tadema and photography", in E Becker and E Prettejohn (eds) Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Rizzoli, New Yoork, 2006 at 111 ff.

68. Kosinski, op cit at 121; Sweetman, D, Paul Gauguin: A Complete Life, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1995 at 269. Conversely, the Australian painter/photographer HJ Johnstone, who left Australia in 1876, evidently used photographs as a basis for Australian landscapes which he continued to paint and sell in the Australian market even though he had become based overseas.

69. Kosinski, op cit at 124; Sweetman, op cit at 252.

70. Gauguin was evidently less concerned with the inherent meanings of the works, than with his own reactions to them. For example, the Marquesas Islands where Gauguin was living were the site of the largest stone sculptures in the archipelago, which some regarded as the equal of the Easter Island stone heads, but Gauguin made no effort to go there, instead relying on a photograph (Sweetman, op cit at 419, 502).

71. Jacobsen, op cit at 70–73.

72. Jacobsen, op cit at 69. For example, Gerome’s 1868 expedition included his son-in-law, a photographer whose images Gerome later used in his work.

73. Smith, L, Victorian Photography, Painting and Poetry – the Enigma of Visibility in Ruskin, Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York, 1995 at 96.

74. Photographs of exotic places could also have indirect influences on painters by inspiring artists to travel and paint there. Bierstadt, for example, was motivated to travel to the Yosemite Valley to paint after seeing photographs of it.

75. Jacobsen, op cit at 71. John Ruskin was extremely enthusiastic about photography's capacity to permanently and accurately document buildings that were were at risk of decay, such as in Venice. William Powell Firth also used photographs as the basis for the detailed interior of Paddington station in his The Railway Station (1862), the painting shown in our masthead.

76. Vaizey, op cit at 41.

76a. Compare for example, Gustave le Gray's photographic seascapes with Courbet's later Marine, Moon Effect (1869).

76b. The first convincing photographs of lightning strikes, by William Jennings in 1882, revealed how earlier painters had not been able to capture their complexity https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-artists-have-so-much-trouble-painting-lightning-180969323/

77. For example, Eakins had numerous photographic nudes displayed in his studio for purposes of close study. A rather different example is provided by Frederick McCubbin’s painting Ti Tree Glade (1897) which depicts a Fresian cow with uniquely distinctive markings identical to those shown in a photograph in his scrapbook (Gaskins, op cit at 346). Of course, the only real significance of this is to show that he copied the pattern from the photograph – it would have made very little difference to the painting itself, and none at all to the course of art history, if he had produced a different pattern.

78. McCauley, op cit at 171.

79. For example, by Delacroix (Koetzle, op cit at 35)

80. The photos were Matthew Brady’s 1862 studies of the Civil War battlefield at Antietam.

81. This mixture of accuracy and art is neatly reflected in the fact that he signed the painting “Manet, June 19, 1867”, which was actually the date of Maximilian’s execution, not the date of the painting (Koetzle, op cit at 82; Frizot M (ed), A New History of Photography, Konemann, Cologne 1998 at 142).

82. Homer was originally employed by Harpers Weekly to create images from photographs of the war.

83. Oliver Wendell Holmes was a strong supporter of the use of photographs instead of photographs for war subjects. Writing in 1863, he stated: “It is well enough for some Baron Gros or Horace Vernet to please an imperial master with fanciful portraits.... (but) war and battles should have truth for their delineator”.

84. Artistic trends in war art are difficult to isolate because they may be so much influenced by other factors such as waves of patriotism, the requirements of “official” art and censorship. For example, while the French were obsessed with depictions of Napoleon before his defeat in 1815, British artists only became more interested after that date.

85. For example,Monet (Vaizey, op cit at 29)

86. Cumming, op cit at 194.

87. McCauley, op cit at 193.

88. Baldassari, op cit at 290. At 301, Baldassari cites the view that a black and white photo of a canvas by Picasso gives us a fairly clear understanding of the painting’s construction, since it is primarily the rightness of the light/dark colour values that accounts for the coherence of the pictorial scaffolding.

89. Koetzle, op cit at 100.

90. Courbet evidently had himself photographed more than any other painter in nineteenth century France (Cumming, op cit at 194).

91. Malraux’ original term was “musée imaginaire”. In the 20th century, its scope has of course been extended almost exponentially by the invention of the Internet

92. Eggum, op cit at 9.

93. Benjamin, W, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, in Arendt, H (ed), Illuminations, Jonathan Cape, London, 1970. Some of these concerns were popularised in Berger, J, Ways of Seeing, BBC/Penguin Books, London, 1972 at 19ff.

94. Baldassari, op cit at 302. Picasso commonly took gestures, looks and positions from a variety of sources, including photos and art reproductions, and creatively adapted them (op cit at 293). This approach found an extreme expression in the collages he produced, with facsimiles of real life documents or objects being incorporated into his paintings. Later, artists would start incorporating actual photographs in this way – for example, the Russian Klutsis, who in 1919 included a photograph of Lenin marching in a propaganda painting depicting the electrification of the country (Frizot, op cit at 437). This trend ultimately may have had some influence in altering conceptions of what constituted legitimate subjects of art.

95. Rothenstein, Sir J, The Moderns and their World, Phoenix House Ltd, London, 1957 Introduction at 14.

96. For example,Malraux commented that,“In our museum without walls, picture, fresco, miniature, and stained-glass window seem of one and the same family. For all are alike – miniatures, frescoes, stained glass, tapestries, Scythian plagues, pictures, Greek vase paintings, ‘details’ and even statuary have become ‘color-plates’. In the process they have lost their properties as objects; but, by the same token, they have gained something: the utmost significance as to style that they can possibly acquire. Thus it is that, thanks to the rather specious unit imposed by photographic reproduction on a multiplicity of objects … a ‘Babylonian style’ seems to emerge as a real entity, not a mere classification” (Malraux, A, The Voices of Silence, trans. Gilbert, S, Princeton University Press, 1978, at 44, 46).

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015. 2017

Back to Pt 1: Initial impacts

Pt 3: Photographic effects

Pt 4: New approaches to “reality”

Citation: Philip McCouat, "Early influences of photography on art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home

35. Millais even remarked that all artists were using photographs, but this is certainly exaggerated (Vaizey, op cit at 21).

36. Koetzle, op cit at 35.

37. Vaizey, op cit at 26.

38. Johnson, op cit at 81. Photographer Oscar Rejlander expressed the relationship quite tactfully in his self-explanatory study Infant Photography Gives Painter an Additional Brush (1856).

38a. For example, in England, the London Stereoscopic Company regularly advertised “100,000 charming stereoscopic views from all parts of the world, and groups of figures representing almost every incident in human life, from 6 shillings per doz”.

39. For example, in 1870, the well-known publisher, editor and seller of photographs, Auguste Giraudon, announced that he had commissioned a painter to do a series of photographic studies of peasants at work in the forest near Barbizon. The results were to be sold to artists to be used as generating images for their own efforts. The tradition of providing "documents for artists" was later carried on by photographers such as Eugene Atget, with his atmospheric photographs of turn-of-the-century Paris.

40. When Corot died, hundreds of photographs were found in his studio. The American heroic landscapist Frederick Church had some 4,000 photographs from all round the world, including vines, ferns waterfalls and palms, and clouds under varying conditions and at different times of the day. Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema had over 5,000. Delacroix had an album of photographic studies, which he called his “treasures”. Moreau had hundreds. Courbet and Millet collected many photographs for reference in painting light and shading. Later, Picasso would collect thousands of art reproduction, ethnographic postcards, regional photographs (Baldassart, A, “Picasso 1901-06: Painting in the Mirror of the Photograph” in Kosinski, D, (ed) The Artist and the Camera: Degas to Picasso, Dallas Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2000, at 289).

41. Campbell, L, “Time and the Portrait” in Lippincott, op cit at 190. In contrast, Van Dyke reputedly worked at exceptional speed, with individual sittings limited to one hour, and up to 14 sittings a day.

42. Campbell, op cit at 190. The Earl was exaggerating slightly – the portrait was eventually exhibited in 1821 when the child was 11.

43. McPherson, H, The Modern Portrait in Nineteenth Century France, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001, at 1.

44. Hughes, R, Nothing If Not Critical, The Harvill Press, London, 1995 at 116. The young woman was Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal.

45. Vaizey, op cit at 28.

46. Sickert’s own practice was to paint the rough outline of the sitter’s likeness and form onto the canvas, in what seemed to him a characteristic pose. He then had the sitter photographed in the same pose and worked thereafter from the photograph (Baron, W, Sickert, Phaidon, 1973).

47. For example, in 1873 Watts asked sitter Sir Charles Dilke to “bring some good photographs. They help to make my acquaintance with peculiarity and shorten the sittings necessary” (Maas, op cit at 200).

48. Eggum, op cit.

49. The evidence includes: (1) Ingres’ undoubted interest in photography, and the use of it to record his own works; (2) the lateral reversal of the image from earlier studies; (3) the pose of hand to chin, which recalls the photographic convention that had developed to enabler sitters to support their heads; (4) the cropping of the edges; and (5) the silvery metallic appearance, which contrasted with Ingres’ earlier works

50. Various other figures in that painting are also based on photographs. Letters survive which indicate his broad ranging requests to friends and other photographers for images (Vaizey, op cit at 21).

51. Photographs also could not rival the heroic size of many of Courbet’s canvases.

52. Muysers, C, “Physiology and Photography: The Evolution of Franz von Lenbach’s Portraiture”, Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide, Vol 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2002 (www.19thc-artworldwide.org, accessed January 2010).

53. Jacobsen, op cit at 72.

54. Gaskins, op cit at 344, 369.

55. Vaizey, op cit at 44.

56. McCauley, op cit at 172.

57. He actually reconstructed the scene by getting participants to pose for 182 photos and did the painting 18 years after the event (Gaskins, op cit at 317). Similarly, William Powell Firth used photographs to capture the complex, crowded scenes of Derby Day (1858).

58. Snapshots he took of other notables for this purpose were not successful (Gaskins, op cit at 317). A folksy American example is provided by Cornelia Adele Fassett, who used photographs in her painting The Florida Case before the Electoral Commission (1879), which included over 250 portraits, some of which are based on photographic portraits by Matthew Brady (http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/art/artifact/Painting_33_00006.htm, accessed Jan 2010; United States Senate Catalogue of Fine Art, p 122ff)).

59. For example, Australia’s first locally trained artist William Dowling painted the late father of his patron William Robertson from a photograph (“Masterpieces from the Nation Fund”, artonview 61 Autumn 1010 NGA p 4). Matisse made four posthumous drawings of his sister in law from photographs (Gilot, F, Matisse and Picasso: A Friendship in Art, Doubleday, 1990 at 179).

60. Rideal, L,“The Developing Portrait – Painting Towards Photography”, National Portrait Gallery, www.npg.org/uk, consulted January 2010.

61. For example, Thomas le Clear’s Interior with Portraits, discussed earlier.

62. For example, Renoir’s portrait of a young girl in Mlle Romaire Lacaux (1864) shares the pose, lighting, and psychological moment it portrays with a carte of an unidentified figure by Disderi (McCauley, op cit at 200).

62A. Pamela Simpson, Corn Palaces and Butter Queens: A History of Crop Art and Dairy Sculpture, University of Minnesota Press, 2012, at 143.

62B. Though Degas was not averse to requiring his female models to endure long periods of severe discomfort in holding difficult poses.

63. A similar point could be made about Caillebotte’s The Oarsmen (1872). Both these paintings also exhibit other photographic elements such as close-ups and cut-off foregrounds: see later discussion.

64. Degas is an obvious example, though the degree to which the use of photographs actually influenced his painting is problematic: see later discussion. The Dutch painter Bakker-Korff temporarily gave up painting because of failing eyesight, but in 1859 started painting small-scale, realistic genre scenes based on photographs. See generally Trevor-Roper, T, The world through blunted sight: An inquiry into the influence of defective vision on art and character, Bobbs-Merrill, New York, 1970. As a modern example, Balthus adjusted his working style from drawing to photography in order to compensate for a loss of precision resulting from old age and illness.

65. Some critics argued thatthe Pre-Raphaelites in fact relied too much on photographs, citing for example the close similarities between Seddon’s Jerusalem and the Valley from the Hill of Evil Counsel (1854) from photos taken on site (Scharf, op cit at 102). In this particular case, the criticism seems harsh – Seddon had spent 120 extremely uncomfortable days doing the painting on site and used the photograph only to finish off in the studio.

66. Hughes (Critical), op cit at 141.

67. This artist had 150 volumes of photographs which he described as being of the “greatest use” to painters (Vaizey, op cit at 20); Ulrich Pohlmann, "Alma-Tadema and photography", in E Becker and E Prettejohn (eds) Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Rizzoli, New Yoork, 2006 at 111 ff.

68. Kosinski, op cit at 121; Sweetman, D, Paul Gauguin: A Complete Life, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1995 at 269. Conversely, the Australian painter/photographer HJ Johnstone, who left Australia in 1876, evidently used photographs as a basis for Australian landscapes which he continued to paint and sell in the Australian market even though he had become based overseas.

69. Kosinski, op cit at 124; Sweetman, op cit at 252.

70. Gauguin was evidently less concerned with the inherent meanings of the works, than with his own reactions to them. For example, the Marquesas Islands where Gauguin was living were the site of the largest stone sculptures in the archipelago, which some regarded as the equal of the Easter Island stone heads, but Gauguin made no effort to go there, instead relying on a photograph (Sweetman, op cit at 419, 502).

71. Jacobsen, op cit at 70–73.

72. Jacobsen, op cit at 69. For example, Gerome’s 1868 expedition included his son-in-law, a photographer whose images Gerome later used in his work.

73. Smith, L, Victorian Photography, Painting and Poetry – the Enigma of Visibility in Ruskin, Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York, 1995 at 96.

74. Photographs of exotic places could also have indirect influences on painters by inspiring artists to travel and paint there. Bierstadt, for example, was motivated to travel to the Yosemite Valley to paint after seeing photographs of it.

75. Jacobsen, op cit at 71. John Ruskin was extremely enthusiastic about photography's capacity to permanently and accurately document buildings that were were at risk of decay, such as in Venice. William Powell Firth also used photographs as the basis for the detailed interior of Paddington station in his The Railway Station (1862), the painting shown in our masthead.

76. Vaizey, op cit at 41.

76a. Compare for example, Gustave le Gray's photographic seascapes with Courbet's later Marine, Moon Effect (1869).

76b. The first convincing photographs of lightning strikes, by William Jennings in 1882, revealed how earlier painters had not been able to capture their complexity https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-artists-have-so-much-trouble-painting-lightning-180969323/

77. For example, Eakins had numerous photographic nudes displayed in his studio for purposes of close study. A rather different example is provided by Frederick McCubbin’s painting Ti Tree Glade (1897) which depicts a Fresian cow with uniquely distinctive markings identical to those shown in a photograph in his scrapbook (Gaskins, op cit at 346). Of course, the only real significance of this is to show that he copied the pattern from the photograph – it would have made very little difference to the painting itself, and none at all to the course of art history, if he had produced a different pattern.

78. McCauley, op cit at 171.

79. For example, by Delacroix (Koetzle, op cit at 35)

80. The photos were Matthew Brady’s 1862 studies of the Civil War battlefield at Antietam.

81. This mixture of accuracy and art is neatly reflected in the fact that he signed the painting “Manet, June 19, 1867”, which was actually the date of Maximilian’s execution, not the date of the painting (Koetzle, op cit at 82; Frizot M (ed), A New History of Photography, Konemann, Cologne 1998 at 142).

82. Homer was originally employed by Harpers Weekly to create images from photographs of the war.

83. Oliver Wendell Holmes was a strong supporter of the use of photographs instead of photographs for war subjects. Writing in 1863, he stated: “It is well enough for some Baron Gros or Horace Vernet to please an imperial master with fanciful portraits.... (but) war and battles should have truth for their delineator”.

84. Artistic trends in war art are difficult to isolate because they may be so much influenced by other factors such as waves of patriotism, the requirements of “official” art and censorship. For example, while the French were obsessed with depictions of Napoleon before his defeat in 1815, British artists only became more interested after that date.

85. For example,Monet (Vaizey, op cit at 29)

86. Cumming, op cit at 194.

87. McCauley, op cit at 193.

88. Baldassari, op cit at 290. At 301, Baldassari cites the view that a black and white photo of a canvas by Picasso gives us a fairly clear understanding of the painting’s construction, since it is primarily the rightness of the light/dark colour values that accounts for the coherence of the pictorial scaffolding.

89. Koetzle, op cit at 100.

90. Courbet evidently had himself photographed more than any other painter in nineteenth century France (Cumming, op cit at 194).

91. Malraux’ original term was “musée imaginaire”. In the 20th century, its scope has of course been extended almost exponentially by the invention of the Internet

92. Eggum, op cit at 9.

93. Benjamin, W, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, in Arendt, H (ed), Illuminations, Jonathan Cape, London, 1970. Some of these concerns were popularised in Berger, J, Ways of Seeing, BBC/Penguin Books, London, 1972 at 19ff.

94. Baldassari, op cit at 302. Picasso commonly took gestures, looks and positions from a variety of sources, including photos and art reproductions, and creatively adapted them (op cit at 293). This approach found an extreme expression in the collages he produced, with facsimiles of real life documents or objects being incorporated into his paintings. Later, artists would start incorporating actual photographs in this way – for example, the Russian Klutsis, who in 1919 included a photograph of Lenin marching in a propaganda painting depicting the electrification of the country (Frizot, op cit at 437). This trend ultimately may have had some influence in altering conceptions of what constituted legitimate subjects of art.

95. Rothenstein, Sir J, The Moderns and their World, Phoenix House Ltd, London, 1957 Introduction at 14.

96. For example,Malraux commented that,“In our museum without walls, picture, fresco, miniature, and stained-glass window seem of one and the same family. For all are alike – miniatures, frescoes, stained glass, tapestries, Scythian plagues, pictures, Greek vase paintings, ‘details’ and even statuary have become ‘color-plates’. In the process they have lost their properties as objects; but, by the same token, they have gained something: the utmost significance as to style that they can possibly acquire. Thus it is that, thanks to the rather specious unit imposed by photographic reproduction on a multiplicity of objects … a ‘Babylonian style’ seems to emerge as a real entity, not a mere classification” (Malraux, A, The Voices of Silence, trans. Gilbert, S, Princeton University Press, 1978, at 44, 46).

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015. 2017

Back to Pt 1: Initial impacts

Pt 3: Photographic effects

Pt 4: New approaches to “reality”

Citation: Philip McCouat, "Early influences of photography on art", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to Home